Chapter 530 Renal Transplantation

Incidence and Etiology

The incidence of ESRD in pediatric patients in the USA in 2006 according to the USRDS annual report varies by age group (Table 530-1). There is an adjusted incident rate of 14.4 per million population for ages 0 to 19 yr.

| AGE RANGE (yr) | ADJUSTED INCIDENT RATES* PER MILLION POPULATION |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | 9.5 |

| 5-9 | 6.1 |

| 10-14 | 13 |

| 15-19 | 29 |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

* Rates are adjusted for sex and race.

The etiology of ESRD in children varies significantly by age (Table 530-2). Congenital, hereditary, and cystic diseases cause ESRD in more than 52% of children 0 to 4 yr of age, whereas glomerulonephritis and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) account for 38% of cases of ESRD in patients 10 to 19 yr of age. The most common diagnosis in children with transplanted kidneys is structural disease (49%), followed by various forms of glomerulonephritis (14%) and FSGS (12%). Children also often start ESRD therapy with a higher estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate than do adults; in 2001, approximately 50% of patients 0 to 19 yr of age had an eGFR >10 mL/min, compared to approximately 38% in patients 20 yr old.

Table 530-2 COMMON CAUSES OF ESRD IN PEDIATRIC TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS (N = 9854)

| CAUSES | % OF RECIPIENTS |

|---|---|

| Aplasia, hypoplasia, dysplasia | 15.9 |

| Obstructive uropathy | 15.6 |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 11.7 |

| Reflux nephropathy | 5.2 |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 3.3 |

| Polycystic disease | 2.9 |

| Medullary cystic disease | 2.8 |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | 2.6 |

| Prune belly syndrome | 2.6 |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome | 2.6 |

| Familial nephritis | 2.3 |

| Cystinosis | 2.0 |

| Idiopathic crescentic glomerulonephritis | 1.7 |

| MPGN type I | 1.7 |

| Berger (IgA) nephritis | 1.3 |

| Henoch-Schönlein nephritis | 1.1 |

| MPGN type II | 0.8 |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

Immunosuppression

Complications with Immunosuppression Infections

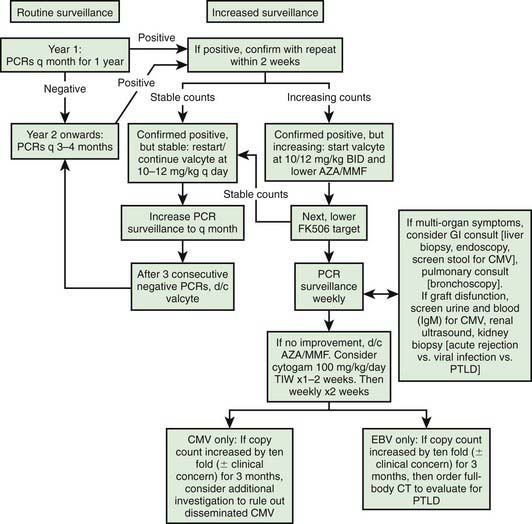

It is important to monitor for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease with routine exams for lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and EBV screen. A schematic plan to monitor for EBV, CMV, and PTLD is provided in Figure 530-1.

Bartsch L, Sarwal M, Orlandi P, et al. Limited surgical interventions in children with posterior urethral valves can lead to better outcomes following renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2002;6:400-405.

Beaunoyer M, Snehal M, Li L, et al. Optimizing outcomes for neonatal ARPKD. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11:267-271.

Benfield MR, Tejani A, Harmon WE, et al. A randomized multicenter trial of OKT3 mAbs induction compared with intravenous cyclosporine in pediatric renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:282-292.

Chrysochou C, Buckley DL, Dark P, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for renovascular disease and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: critical review of the literature and UK experience. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:887-894.

Dharnidharka VR, Stablein DM, Harmon WE. Post-transplant infections now exceed acute rejection as cause for hospitalization: a report of the NAPRTCS. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:384-389.

Ettenger R, Sarwal MM. Mycophenolate mofetil in pediatric renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;80:S201-S210.

Filler G, Webb NJ, Milford DV, et al. Four-year data after pediatric renal transplantation: a randomized trial of tacrolimus vs. cyclosporin microemulsion. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:498-503.

2004 Guidelines for vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(Suppl 10):160-163.

Hocker B, Weber LT, Feneberg R, et al. Prospective, randomized trial on late steroid withdrawal in pediatric renal transplant recipients under cyclosporine microemulsion and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation. 2009;87:934-941.

Kambham N, Nagarajan S, Shah S, et al. A novel, semiquantitative, clinically correlated calcineurin inhibitor toxicity score for renal allograft biopsies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:135-142.

Li L, Chang A, Naesens M, et al. Steroid-free immunosuppression since 1999: 120 pediatric renal transplants with sustained graft and patient benefits. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1362-1372.

Li L, Chaudhuri A, Weintraub LA, et al. Subclinical cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus viremia are associated with adverse outcomes in pediatric renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11:187-195.

McDonald RA, Smith JM, Ho M, et al. Incidence of PTLD in pediatric renal transplant recipients receiving basiliximab, calcineurin inhibitor, sirolimus and steroids. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:984-989.

Moudgil A, Puliyanda D. Induction therapy in pediatric renal transplant recipients: an overview. Paediatr Drugs. 2007;9:323-341.

Renal Business Today. USRDS releases 2007 report. http://www.renalbusiness.com/articles/07novfeat1.html. Accessed March 31, 2010

Sarwal M, Benfield MR, Ettenger RB, et al. One year results of a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial of steroid avoidance in pediatric renal transplantation. In: 5th Congress of the International Pediatric Transplant Association (IPTA). Istanbul: International Pediatric Transplant Association; 2009.

Sarwal M, Chua MS, Kambham N, et al. Molecular heterogeneity in acute renal allograft rejection identified by DNA microarray profiling. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:125-138.

Sarwal MM, Vidhun JR, Alexander SR, et al. Continued superior outcomes with modification and lengthened follow-up of a steroid-avoidance pilot with extended daclizumab induction in pediatric renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76:1331-1339.

Schnuelle P, Gottmann U, Hoeger S, et al. Effects of donor pretreatment with dopamine on graft function after kidney transplantation. JAMA. 2009;302:1067-1074.

Silverstein DM, Aviles DH, LeBlanc PM, et al. Results of one-year follow-up of steroid-free immunosuppression in pediatric renal transplant patients. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:589-597.

Starzi TE. Immunosuppresive therapy and tolerance of organ allografts. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:407-410.

Sutherland S, Li L, Concepcion W, et al. Steroid-free immunosuppression in pediatric renal transplantation: rationale outcomes following conversion to steroid based therapy. Transplantation. 2009;87:1744-1748.

U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Annual report: transplant data 1998–2007. http://www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/current/default.htm. Accessed March 24, 2010

Vo AA, Lukovsky M, Toyoda M, et al. Rituximab and intravenous immune globulin for desensitization during renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:242-251.