114 Renal Failure

• Management of renal failure in the emergency department should be aimed at identifying and treating life-threatening abnormalities associated with the disorder, identifying reversible causes of renal failure, and preventing further injury to the kidneys.

• Acute pulmonary edema and hyperkalemia are potentially life-threatening complications of renal failure.

• Severe hyperkalemia should be suspected as the cause of cardiac arrest in patients with a possible history of renal failure.

• An electrocardiogram should be obtained for all patients with renal failure on arrival at the emergency department to screen for hyperkalemia.

Definitions

The Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) provides the following criteria for the diagnosis of acute kidney injury: an abrupt (within 48 hours) reduction in kidney function currently defined as an absolute increase in serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dL or greater (≥26.4 µmol/L), a 50% or greater increase in serum creatinine of (1.5-fold higher than baseline), or a reduction in urine output (documented oliguria of less than 0.5 mL/kg/hr for more than 6 hours).1

Two classification systems describe the stage of renal disease. The first, created by the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative, is the RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss, and end-stage kidney disease) classification system, which bases severity on the degree of change in serum creatinine or urine output from a baseline measurement (Table 114.1).2 The second was created by AKIN. Although it is modeled on the RIFLE classification, it does not require the physician to know the patient’s baseline creatinine level. Its ease of use in the emergency department (ED) is improved by the fact that it does not use the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as one of the criteria for staging kidney injury. The AKIN criteria are to be applied after adequate fluid resuscitation has taken place, and the authors of the criteria also recommend excluding easily reversible causes of kidney failure, such as urinary outflow obstruction (Table 114.2).1

| GFR CRITERIA | URINE OUTPUT CRITERIA | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk | Increased Cr × 1.5 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hr × 6 hr |

| or | ||

| GFR decreased >25% | ||

| Injury | Increased Cr × 2 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hr × 12 hr |

| or | ||

| GFR decreased >50% | ||

| Failure | Increased Cr × 3 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hr × 12 hr |

| or | or | |

| GFR decreased >75% | anuria × 12 hr | |

| Loss | Persistent ARF = complete loss of renal function for >4 wk | None |

| End-stage kidney disease | End-stage kidney disease > 4 mo | None |

Cr, Creatinine; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; UO, urine output.

Table 114.2 AKIN Criteria for Staging Acute Kidney Injury

| CREATININE CRITERIA | URINE OUTPUT CRITERIA | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Increased Cr × 1.5 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hr > 6 hr |

| or | ||

| Increased ≥0.3 mg/dL | ||

| Stage 2 | Increased Cr × 2 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hr > 12 hr |

| Stage 3 | Increased Cr × 3 | UO < 0.5 mL/kg/hr > 24 hr or anuria for 12 hr |

| or | ||

| ≥4 mg/dL with acute increase of 0.5 mg/dL | ||

| or | ||

| Patient receiving renal replacement therapy |

AKIN, Acute Kidney Injury Network, Cr, creatinine; UO, urine output.

The National Kidney Foundation’s clinical practice guidelines define patients with chronic kidney disease as meeting one of the following criteria: (1) kidney damage for 3 or more months, defined as structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without an increased GFR, and demonstrated by either pathologic abnormalities or markers of kidney damage, including abnormalities in blood or urine or abnormal findings on imaging tests; or (2) a GFR lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 3 or more months, with or without kidney damage.3 The complicated definition of chronic kidney disease plus the need to monitor kidney function over an extended period means that it is unlikely that chronic kidney disease will be convincingly diagnosed in the ED. However, it is useful for the emergency physician (EP) to understand what it means when a patient has preexisting chronic kidney disease, as well as to be vigilant for suspected, but previously undiagnosed chronic kidney disease in a patient with the appropriate signs and symptoms.

Epidemiology

The prevalence and incidence of kidney failure in the United States are rising. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease is estimated to be greater than 10%.4 The annual incidence of acute kidney injury is 100 per 1 million population. The incidence of acute kidney injury in the community varies widely depending on the population, but hospital-acquired rates can be quite high, with as many as 30% of critical care patients in some studies developing acute kidney injury.5

Pathophysiology

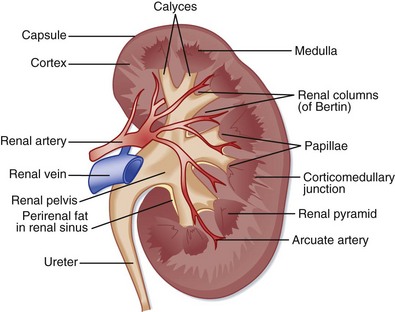

The kidneys are located in the retroperitoneal space and are composed of three basic structures: vasculature, parenchyma, and the collecting system. The kidneys receive about a quarter of the body’s total cardiac output through the renal arterial system and an extensive network of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries that eventually drain into the renal vein. The renal parenchyma is composed of the medulla and cortex, which houses the functional unit of the kidney, the nephron. A single nephron consists of a glomerulus, proximal tubule, thin limbs of Henle, and a distal tubule. The connecting tubule joins the nephron to the collecting system, including the renal pelvis, minor and major calyces, and the ureter, bladder, and urethra (Fig. 114.1).

1. Prerenal failure results from the kidneys not receiving enough blood via a cause external to the kidneys themselves; it results in a reduced GFR, buildup of toxic waste products, and damage to the kidneys persisting after the underlying cause has been corrected. Causes of prerenal failure include hypovolemia, decreased cardiac output, and septic shock.

2. Renal failure may be caused by diseases intrinsic to the kidneys, including genetic syndromes such as polycystic kidney disease, infections, vascular diseases, and toxins or drugs.

3. Postrenal failure may result from obstruction to urinary flow external to the kidneys themselves. The obstruction causes increased fluid pressure within the nephron, which ultimately leads to loss of function. Ureteral stones, prostatic hypertrophy, tumors, and anticholinergic medications are some possible causes of postrenal kidney failure.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Manifestations may vary greatly depending on the cause of the renal failure, but patients may describe a history of volume overload or decreased urine output. They may also have one or many of a long list of end-organ effects (Table 114.3). Renal failure is not a diagnosis that is necessarily obvious on initial encounter and is often made only after screening laboratory data are obtained.

| ABNORMALITY CAUSED BY RENAL FAILURE | PHYSICAL FINDINGS, END-ORGAN EFFECT |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | |

| Pulmonary edema | Crackles |

| Hypertension | |

| Pericardial effusion | |

| Metabolic | |

| Hyperkalemia | Peaked T waves, arrhythmias, bradycardia, cardiac arrest |

| Hypocalcemia | Tetany, cardiac arrhythmias |

| Hypermagnesemia | Nausea and vomiting, arrhythmias |

| Neurologic | |

| Uremia | Seizures |

| Acute and chronic neurologic changes | HyperreflexiaEncephalopathy, including asterixisSensory neuropathy |

| Hyponatremia or hypernatremia | Altered mental status, seizures |

| Dialysis-associated dementia | Loss of cognitive function |

| Immunologic | |

| Immunosuppression | Recurrent infections |

| Pulmonary | |

| Fluid overload: pleural effusions, pulmonary edema | Shortness of breath, hypoxia, crackles, dullness to percussion, peripheral edema |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Gastritis | Abdominal pain |

| Bleeding | Melena |

| Malnutrition | Cachexia, anemia |

| Endocrine | |

| Glucose intolerance | Hyperglycemia |

| Renal osteodystrophy Myopathy Amyloid arthropathySecondary hyperparathyroidism | Bone and joint pain, myalgias |

| Skin | |

| Uremia | Pruritus, uremic frost (urea crystals from sweat on skin) |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Uremic pericarditis | Pericardial friction rub, chest pain worse with lying down, ECG changes: ST elevation and PR depression (only some or none of these may be seen) |

| Myocardial infarction | ST elevation in anatomic distribution or elevated enzymes |

| Acidosis | Hypotension |

| Hematologic | |

| Uremic platelets | Bleeding |

| Musculoskeletal | |

| Arthritis | |

| Spontaneous tendon rupture | |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | |

ECG, Electrocardiographic.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Once a diagnosis of renal failure is made through creatinine screening or the presence oliguria or anuria (Box 114.1), a differential diagnosis of underlying conditions and complications should be generated by considering potential diseases of the vasculature, parenchyma, and collecting system, as well as conditions external to the kidneys that lead to decreased blood flow or obstruction to the flow of urine.

Box 114.1 Diagnostic Criteria for Acute Kidney Injury

Intrinsic Renal Failure: Vascular Causes

Vascular diseases of the kidney are manifested differently according to the size of the artery involved (Box 114.2). Sudden back or flank pain suggests large vessel aneurysm, dissection, embolism, or trauma. Poorly controlled hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency suggest renal artery stenosis. Systemic manifestations such as rash and fever suggest vasculitis in the smaller vessels of the kidney.

Intrinsic Renal Failure: Parenchymal Causes

The working unit of the kidney is the nephron, which is composed of a variety of cell types that are susceptible to many disease processes (Box 114.3). The medical history is invaluable in identifying the root cause within this category of kidney failure.

Obstructive Renal Failure

The collecting system of the kidneys is composed of the calyces, renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, and urethra—obstruction may occur at any level (Box 114.4). Obstruction to urinary flow is generally a reversible cause of renal failure. Alert patients may have symptoms of urinary retention or nephrolithiasis that are dramatic and obvious. Occult, potentially reversible renal obstruction should be considered in patients with altered mental status and acute renal failure.

Urine Formation Problems Resulting in Renal Failure

Also known as prerenal kidney failure, problems with urine formation should be suspected in patients with volume depletion, decreased cardiac output, or third spacing of fluid as a result of any cause. The various causes of prerenal kidney failure are summarized in Box 114.5.

Treatment

Hospital Management

Treating Reversible Causes of Renal Failure

The use of specific antidotes and pharmacologic treatments (e.g., bicarbonate and mannitol for patients with rhabdomyolysis) and the use of diuretics to improve urine flow are controversial; consultation should be obtained before initiating any therapy (beyond fluid replacement) aimed at maintaining adequate urine output.6

Other Treatment Considerations

Intravenously administered contrast material may cause additional kidney injury. If patients are receiving renal replacement therapy, contrast material may be administered in consultation with a nephrologist if dialysis is to take place in a timely manner (Box 114.6).

Life-Threatening Complications of Renal Failure

Volume Overload

Hyperkalemia

Uremic Pericarditis

Dialysis-associated pericarditis can also occur. It is not well understood, but large effusions may be present and require either increased dialysis or surgical correction.7

Pericardial Tamponade

Many patients with long-standing renal failure have preexisting pericardial effusions and volume overload that complicate the diagnosis of pericardial tamponade. Chest radiography may not reveal classic abnormalities in heart shape because many patients may have coincident cardiomegaly. Echocardiographic findings may also be altered.8

Hemorrhage

Prolongation of the bleeding time, decreased activity of platelet factor 3, abnormal platelet aggregation, and impaired prothrombin consumption contribute to the abnormal hemostasis in patients with renal failure. Patients may have abnormal bleeding as a result of minor wounds or surgery, epistaxis, spontaneous gastrointestinal bleeding, or hemorrhage in the liver, pericardial sac, or brain. Gastrointestinal bleeding is both more common and more severe in patients being maintained on renal replacement therapy.7 Patients with renal failure may have preexisting anemia, and therefore small drops in hemoglobin may be detrimental. Blood transfusions that maintain the hematocrit above 30% have been shown to improve platelet dysfunction. Desmopressin, erythropoietin, cryoprecipitate, and conjugated estrogens may all be of benefit (Box 114.7).

Box 114.7

Interventions to Reduce Bleeding in Patients with Renal Failure

Packed red blood cell transfusions

Data from Dember LM. Critical care issues in the patient with chronic renal failure. Crit Care Clin 2002;18:421-40.

Complications of Renal Replacement Therapy

Renal replacement therapy produces its own unique set of complications. Patients with grafts and fistulas may have infections, bleeding, or thrombosis of their access sites. Port malfunction, infection, or peritonitis may develop in peritoneal dialysis patients. Dialysis-related complications include hypotension and disequilibrium syndrome (refer to Chapter 116 for a detailed discussion of dialysis-related emergencies).

Consultation

Urgent nephrology consultation should be obtained for patients with volume overload or significant electrolyte abnormalities requiring dialysis. Indications for dialysis are summarized in Boxes 114.8 and 114.9.

Box 114.8 Indications for Dialysis in Patients with Chronic Renal Failure

Box 114.9 Indications for Dialysis in Patients with Acute Kidney Disease

Next Steps in Care

Prognosis

The prognosis of an individual patient with renal failure depends on a multitude of factors—the underlying cause of the renal failure, the patient’s preexisting renal function, and comorbid conditions. In patients with chronic kidney disease, the mortality rate, especially from cardiovascular causes, is much higher than in the general population and worsens as kidney function decreases.3

Albright R. Acute renal failure: a practical update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:67–74.

Dember LM. Critical care issues in the patient with chronic renal failure. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:421–440.

Minnaganti V, Cunha B. Infections associated with uremia and dialysis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:385–406.

1 Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31.

2 Kellum JA, Ronco C, Mehta R, et al. Consensus development in acute renal failure: the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:527–532.

3 National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Accessed online March 25, 2011. Available at http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_ckd/toc.htm

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), CDC; 2010.

5 Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844–861.

6 Albright R. Acute renal failure: a practical update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:67–74.

7 Dember LM. Critical care issues in the patient with chronic renal failure. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:421–440.

8 Klein LW. Diagnosis of cardiac tamponade in the presence of complex medical illness. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:721–723.