CHAPTER 58 Rehabilitation Methods in Cervical Radicular Pain

Treatment of cervical radiculopathy spans the spectrum from medication and activity modulation through surgical decompression. Treatment recommendations are based on the specific patient’s history and physical findings. The wide variation in the approach to similar patterns of patient symptoms, history, and findings is indicative of the lack of clear evidence-based practice algorithms. The armamentarium of treatments available includes medications, activity modification, rest, physical therapy, bracing, complementary medicine techniques, spinal injections and percutaneous procedures and surgery.1–8 Nonsurgical treatment has been shown to be effective and safe for cervical radiculopathy, with outcomes similar to those for surgical intervention.1,2,5,7 The decision of which treatment to recommend and its timing is primarily based on the physician’s experience and training, with little conclusive empirical evidence in most cases. Approaching treatment based on history and exam and response to treatment with reevaluation and modification of the treatment plan as indicated is a sensible approach.

MEDICATIONS

There are many classes of medications available to treat cervical radicular pain.2,6 For pain and presumed inflammation nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often used as the first line of medication therapy. Traditional NSAIDs are generally recommended unless there is a contraindication such as a history of ulcer disease or upper GI bleed. The controversy surrounding the use of COX-2 selective antiinflammatory agents continues to evolve. At issue are cardiovascular adverse events, which led to the voluntary withdrawal of Vioxx by Merck on September 30, 2004. The recent FDA hearings (February 2005) seem to suggest that these drugs should be restricted to use in patients who are in the category of those patients at elevated risk for GI adverse events with low CV risk factors. At the time of the final edit of this chapter the formal outcome of the hearings and the recommendations/package insert changes were not known.

Narcotic medications are the mainstay of treatment for pain unresponsive to NSAIDs. The American Pain Society recommends opioids for acute pain when non-opioids fail.9 For episodic pain or short-term usage, short-acting narcotics are effective. Patients with constant moderate to severe pain are better treated with long-acting narcotic medications (sustained release) for a stable level of pain control. They avoid the peaks and troughs often associated with short-acting prn medications.

Adjuvant medications are often useful for pain management to help decrease narcotic usage and, in certain cases, control pain without narcotics. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are the most studied medicine for neuropathic pain. They are utilized in lower doses than would be given for depression.10 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants may be beneficial for pain management in some patients. One of the benefits of TCAs is their sedating effect on most patients. Patients often have difficulty sleeping so if the TCA is taken at night it serves a dual purpose. Gabapentin has been helpful in treating neuropathic pain as have other anticonvulsants.11

Steroids orally and via spinal injections are another medication option. Oral steroids may be beneficial when NSAIDs fail2,6 but treat a focal problem with a systemic treatment. Muscle relaxers, major tranquilizers, and hypnotics may also be tried for pain relief. There are also other pain medications which are often helpful such as tramadol, a non-scheduled pain medication which acts at the opioid receptors.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A patient with radicular pain that brings them to the doctor, for the most part, requires diagnostic work-up to identify the cause of the radiculopathy. In general, X-rays with dynamic views and MRI imaging are helpful to evaluate for instability and to identify any neural impingement. If MRI is not an option, CAT scan may be helpful to elucidate the anatomy and cause of the radiculopathy. If there is a question of a systemic process, bone scan and lab studies are indicated. In patients without a clear localization of radiculopathy to a specific root level, or if there is a question of plexopathy, peripheral entrapment or polyneuropathy, EMG and NCS are often helpful.12

BRACING

For comfort, a soft cervical collar may be worn, particularly when traveling. The negative effect is that it may lead to further deconditioning of the neck muscles. A soft collar may also help with sleep. For sleep, keeping the neck in a neutral position with pillows or a cervical pillow is beneficial. Rigid collars have also been used to treat cervical radiculopathy.2,4,5,13 There are no controlled studies showing a beneficial effect compared to no treatment but use of a collar has been part of a conservative treatment program that was effective. In one study, cervical collars were shown to have the same outcome at 16 months as surgery or physical therapy.5

PHYSICAL THERAPY

Introduction

Because the superiority of any one rehabilitation method for cervical radiculopathy has not been firmly established, many physical therapists use a combination of conservative interventions. Some of the methods and techniques are evidence-based, while others are anecdotal or traditional. These interventions may include repeated movement exercise, manual techniques, modalities, traction, neural mobilization, dynamic stabilization exercise, postural training, patient education and ergonomics. Although research is inconclusive, there have been a number of studies published advocating the effectiveness and success of conservative rehabilitation treatment.1–3,14,15 The success of any rehabilitation treatment plan begins with the evaluation. An effective evaluation utilizes signs and symptoms, which the clinician identifies during the history and physical examination to govern clinical decision-making.16,17 Treatment decisions are made based upon a patient’s symptom response to movement and the mechanical stresses that reproduce these symptoms.16,17 This type of interactive evaluation enables the clinician to develop a treatment algorithm. The algorithm presented in this chapter can be used to direct treatment, categorize patients into different treatment paradigms, and determine the most appropriate intervention to create an objectively based treatment program.

Patient evaluation

Posture analysis is typically performed by observing the patient in various positions. Neutral spine posture can be defined as ‘a vertical line passing through the lobe of the ear, the seventh cervical vertebra, the acromion process, the greater trochanter, just anterior to the midline of the knee, and slightly anterior to the lateral malleolus.’18 Postural abnormalities may be the result of habitual adoption of poor posture or the result of an acquired deformity. The common habitual postural abnormality that the clinician should be aware of is termed the forward head position. In this position, kyphosis or flexion of the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine causes a compensatory extension or excessive lordosis in the upper cervical spine to achieve a level head position.19 Over time, excessive upper cervical lordosis may be a source of headaches, and excessive lower cervical kyphosis may lead to cervical radicular pain.19–21 There are two acquired cervical postural deformities associated with cervical radiculopathy: kyphosis and torticollis.16,22,23 In both cervical kyphosis and acute cervical torticollis, patients become locked in a protective position and are unable to move out of this acquired deformity. The physical examination continues with a range of motion assessment, which is divided into physiologic and accessory motion. The physiologic motion, or the normal gross movements of the cervical spine, includes retraction and protrusion, sagittal plane extension and flexion, transverse plane rotation and coronal plane lateral flexion (side-bending) (Table 58.1). Accessory motion is the gliding of one cervical segment on another. Assessment of accessory motion is segment specific and assists the clinician in determining the possible level of the pathology.

| Movement | Range of normal motion |

|---|---|

| Upper cervical flexion and extension | 1–15° |

| Cervical flexion | 80–90° |

| Cervical extension | 70° |

| Cervical rotation | 70–90° |

| Cervical lateral flexion | 20–45° |

Neurologic and specialized cervical spine testing is essential when evaluating and treating patients with cervical radiculopathy. The neurologic exam should consist of myotome, dermatome, neural tension signs, and muscle stretch reflex testing. Patients experiencing radicular symptoms must have their myotomes and reflexes tested at each visit to monitor any changes. Special testing for the cervical spine includes Spurling’s, vertebral artery insufficiency and instability testing. Repeated movement testing evaluates patient responses to precisely controlled, repetitive spinal motion. Repeated movements causing pain to retreat to a more central location are favorable toward treatment outcomes, and those causing pain to travel more peripherally are undesirable.16,24–28 Centralization is the process by which pain, originating from the spine, retreats to a more central location and remains as a result of performing certain repeated movements, or adopting certain positions.16 Centralization of referred pain can be utilized as a diagnostic tool, as well as a means of identifying patients who will respond to conservative rehabilitation.24–27

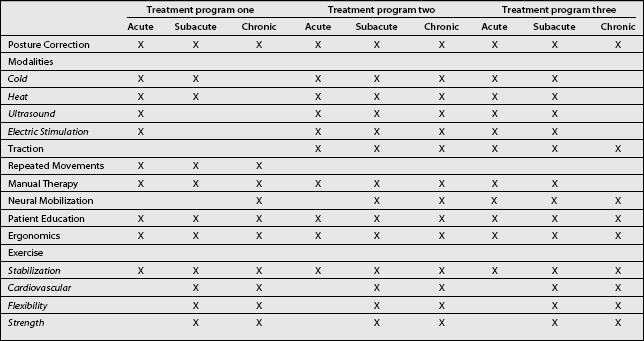

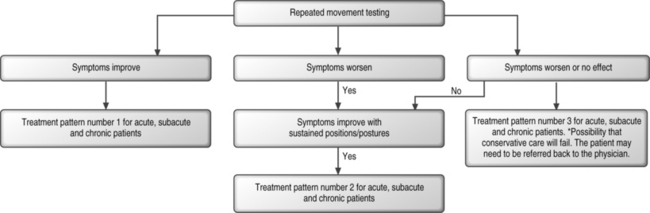

Sagittal plane movements are exhausted prior to examining coronal and transverse plane movements. Once the repeated movement test is complete, the clinician assesses the patient’s response and can utilize the algorithm to direct treatment. This pattern of assessment as part of a thorough evaluation process will allow the clinician to properly classify the patient into certain treatment patterns and therefore determine the most effective treatment interventions. These treatment interventions will be explained in more detail in the remaining portion of this chapter. Table 58.2 and Figure 58.1 present the fundamental clinical reasoning of the experienced clinician. The algorithm provides a structured method of assessing patient symptoms and selecting an appropriate treatment pattern (Fig. 58.1). Epidemiological evidence and time frame of injury have been used to generalize acute, subacute, or chronic injury and, to some extent, treatment. However, physical therapy treatment should be based on clinical presentation and response to repeated movement testing. Three treatment patterns have been established based upon patient response to repeated movement testing (Table 58.2). Each treatment pattern contains a variety of techniques used to treat cervical radiculopathy. Treatment patterns one and two are designed for patients who respond positively to repeated movements and/or sustained positions and postures. Patients in this category typically have a better prognosis.24,25,27,29 Treatment pattern three is designed for severely irritable tissues. Patients in this category are unable to tolerate repeated movements or sustained positions and postures. All movements and postures tend to worsen symptoms or have no effect. Patients may require further medical treatment prior to initiating a rehabilitation program or even fail conservative treatment measures.26

REHABILITATION METHODS FOR CERVICAL RADICULOPATHY

Posture

Correction of abnormal posture is used as a treatment tool to reduce abnormal and unnecessary strain, to aid in the resolution of nerve root irritation and to prevent recurrence. Patients with an acute condition will use positioning and posture to alleviate pain. The goal is to minimize pain and create an optimal healing environment for the damaged tissues. Once the condition is no longer acute and the patient is able to tolerate movements, attempts of attaining and maintaining a neutral cervical spine posture may begin. It has been reported that through the performance of an exercise program one can change one’s resting spinal posture.30,31 It has been recommended that through performing repeated cervical retraction exercises, pulling the head and neck posteriorly into a position in which the head is aligned more directly over the thorax, one can decrease the forward head posture, achieve a more neutral resting cervical spine position, increase the diameter of the neural foramen, and reduce nerve root irritation.16,18,30,32,33 This kinesthetic awareness, of achieving and maintaining a neutral cervical spine posture, is critical in the maintenance and possibly in the prevention of recurrent cervical radiculopathy.

Modalities

Modalities refer to physical agents and electrotherapy methods. Physical agents are tissue cooling and heating techniques, including ultrasound. Additionally, there is a multitude of electrotherapy techniques available to the clinician. Modalities produce physiologic effects, such as promoting increased tissue extensibility, increased blood flow, spasm reduction, and pain relief that may be useful in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. It is incumbent upon the clinician to understand the physiologic effects of the available modalities and apply them appropriately, relative to the patient’s condition. The use of heat and ice is often indicated in the early stages of treatment. The goal of their application is twofold: break the pain–muscle spasm cycle, and promote early use of movement-oriented treatment techniques. As such, their application and efficacy, while continually debated, is justified. The choice of heat or ice is empirical and largely depends on patient comfort. Cooling and heating effects of superficially applied modalities change tissue temperatures at minimal depths, and likely do not effect change at the depth of the nerve root. The depth of penetration of superficial heat has been reported to be 1–2 cm at best and insufficient to reach deep soft tissue structures.34 Application of therapeutic heat produces an increased tissue extensibility with resultant decreased stiffness, pain relief, reduction of muscle spasm, reduction of inflammation, and enhanced blood flow.35 Deep heating, through the use of ultrasound has been purported to be beneficial in increasing tissue extensibility through its thermal effects. Therefore, it may play a role in improving range of motion in the restricted cervical spine. Cryotherapy, or the application of therapeutic cold, is used when cooling effects on tissue are desired. Typically, cold is applied in early stages of injury. Analgesia may occur when tissue temperatures are decreased. Motor nerve conduction velocity and muscle spindle firing has been shown to decrease when tissue temperatures drop to 10–15°C.36 This may produce desired relaxation of muscle spasm. Vasoconstriction occurs with the application of cold. That is the rationale for using cold for the reduction of inflammation and edema. Certain heating modalities may not be warranted for patients with an acute cervical radiculopathy. The stage of the patient’s condition and the results of the evaluation must be taken into account for proper selection and application of modalities.

Various forms of electrical therapy have been used to modulate pain. The electrical current can be effective in disrupting the pain and spasm cycle by stimulating the afferent neural pathways, thereby inhibiting protective muscle guarding. Early reduction of pain from electrotherapy, albeit temporary, is a starting point toward a more active rehabilitation process. While the use of modalities specifically for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy has not been extensively studied, they offer the clinician commonly used and viable adjuncts to active treatment techniques. Therapeutic modalities as described here may be used as an adjunct to active intervention, but for the most part their efficacy has not been subjected to intensive clinical trials.37 Nonetheless, sufficient empirical and anecdotal evidence exists, which suggests that these agents do play a role as part of a clinic-based rehabilitation program. In the chronic patient, passive modalities have not been determined to be an effective treatment.16,38,39 Therefore, it is imperative that an active treatment program be initiated as soon as tolerated while the use of modalities is de-emphasized.

Cervical traction

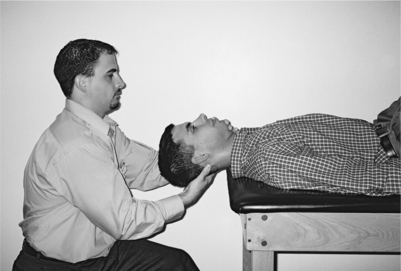

Cervical traction is often used in the treatment of radiculopathy.2,8,40–43 The rationale for traction is based on elongation of the spine, resultant increase in intervertebral space, relaxation of spinal muscles, opening of the neural foramen, and relief of nerve root compression.44–46 With cervical traction, the reduction of compressive forces theoretically serves to create space for the inflamed or compressed nerve root, thereby diminishing structural impingement and improving fluid dynamics. The efficacy of traction has not been conclusively proven in a randomized, controlled trial, but it is commonly used and thought to be beneficial in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy.47,48 Many clinicians advocate manual traction as a means of assessing the patient’s response to the technique prior to employing mechanical devices and as a treatment technique itself. Figure 58.2 represents application of manual traction. The variables of duration, direction of force, and position can be rapidly assessed and easily changed dependent on the pain response. The clinician will be looking for pain to move from a distal to a proximal location and decrease in intensity as a favorable response. Once it has been determined that the response is favorable, mechanical treatment devices can be employed. Should cervical traction produce a desirable effect, home traction units are available.

Concerning duration of traction forces, Colachis and Strohm showed that nearly all vertebral separation occurs during the first seven seconds of force application, but that up to 20–25 minutes is necessary to produce muscle relaxation.40–42 Intermittent traction produces twice the amount of separation as sustained traction and as a result it is currently the mode of choice.49 If improvement is realized, parameters of time and traction force can be increased on a slow gradient until maximum benefit as measured by symptom relief is achieved.

With regard to positioning, traction is typically performed with the patient sitting or supine. The supine position has been shown to provide greater separation of intervertebral spaces from C4 to C7 than sitting, when the angle of pull and force were controlled.50 This suggests that the supine position is superior for the desired separation effect. The angle of pull must be correct to get the desired therapeutic effect. Flexion of 20–30° is advocated to obtain the greatest benefit of posterior muscular elongation and enlargement of the intervertebral foramina.51 There is no firm consensus on the amount of traction force needed to produce a desired clinical result. It appears that at least 25–30 pounds of force are required to produce measurable separation of the cervical vertebrae.41,42,52 The traction force must be at least the weight of the head to produce any significant decompression. Traction is contraindicated in the presence of any disease resulting in structural compromise or instability.53 Examples include tumor, infection, and rheumatoid arthritis. Further, any condition for which movement is contraindicated also is a contraindication for traction.54 Relative contraindications include acute strains and sprains that would be aggravated by traction.19 Traction applied to patients with joint instability may cause further strain and should be carefully monitored if applied at all. Other relative contraindications may include pregnancy, osteoporosis, hiatal hernia, and claustrophobia. A careful patient history should be taken before employing cervical traction to rule out absolute and relative contraindications. It is strongly advised to consult dynamic X-rays first to clear the patient of instabilities that could be aggravated by traction. Unstable spondylolisthesis or atlanto-axial instability is a contraindication for traction. When applying cervical traction, one must be aware of additional risk factors including increased blood pressure, respiratory compromise and temporomandibular joint compression due to the required harness for certain mechanical devices.

Repeated movements and associated manual techniques

As soon as the patient is able to tolerate motion, movements that centralize the radicular symptoms are employed. Refer to Table 58.3, repeated treatment movements and the associated manual techniques. When utilizing repeated movements and associated manual techniques, there is a progression of force that should be followed. Patient generated forces in mid range and then end range are performed first. If the centralization process plateaus, more force is required to fully resolve the patient’s symptoms. Patient generated overpressure can be applied at the end range of motion. If symptoms continue to centralize but plateau once again, additional force, beyond the patient’s capabilities, may be required. At this point, therapist generated forces are necessary to fully resolve symptoms. Therapist applied overpressure is performed first. If little to no improvement has been made, more reductive force is indicated. Mobilization and if necessary manipulation may be added to the regimen. After each therapist applied technique, symptoms are reassessed and the patient is instructed to repeat the movements unaided. Sagittal plane movement and techniques, in weight bearing, are exhausted before performing movements in the coronal plane, transverse plane, and non-weight bearing positions. One exception is a patient who presents with postural torticollis. In most cases, postural torticollis will require lateral flexion and rotational techniques.16 Patients with an acute injury and/or postural torticollis or kyphosis may not be able to tolerate movements in weight bearing. In these cases, patients are treated in a lying position. Lying unloads the motion segment and places it in slight traction, producing less pain with movement. Evidence suggests that symptom reduction is more stable when treated in a weight bearing position.23 Therefore, movements are to be performed in weight bearing whenever possible. Once a directional preference is found, movements in that direction are to be performed for 10 repetitions every 2 hours. The reduction of symptoms is maintained through repetition and posture correction. The correct posture is determined by the directional preference of the treatment. Any adverse strain has the ability to revert compression back upon the cervical nerve root. As symptoms become intermittent and more stable, the repetitions can be reduced by half. When the patient is pain free for 3–4 days the exercises only need to be performed a few times a day and as needed. At this time, the patient may begin restoration of function. The patient is instructed to move in those directions that were once avoided. This is done to restore full range of motion and soft tissue flexibility. Cervical stabilization exercises may safely begin. Finally, the patient is educated in prevention techniques, warning signs of symptom return, and self-treatment techniques.

| Procedures | Plane of Movement |

|---|---|

| Retraction (with/without overpressure, sitting or standing) | Patient-generated, sagittal plane, weight-bearing movement |

| Retraction and extension (with/without overpressure, sitting or standing) | Patient-generated, sagittal plane, weight-bearing movement |

| Retraction and extension (with overpressure, lying supine or prone) | Patient-generated, sagittal plane, nonweight-bearing movement |

| Retraction and extension with traction and rotation (lying supine) | Therapist-generated, sagittal plane, nonweight-bearing mobilization |

| Extension mobilization (lying prone) | Therapist-generated, sagittal plane, nonweight-bearing mobilization |

| Retraction and lateral flexion (with/without overpressure, sitting, standing or supine) | Patient-generated, coronal plane, weight-bearing or nonweight-bearing movement |

| Lateral flexion mobilization and manipulation (sitting or lying supine) | Therapist-generated, coronal plane, weight-bearing or nonweight-bearing mobilization and manipulation |

| Retraction and rotation (with/without overpressure, sitting or standing) | Patient-generated, transverse plane, weight-bearing movement |

| Rotation mobilization and manipulation (sitting or lying supine) | Therapist-generated, transverse plane, weight-bearing or nonweight-bearing mobilization and manipulation |

| Flexion (with/without overpressure, sitting or standing) | Patient-generated, sagittal plane, weight-bearing movement |

| Flexion mobilization (lying supine) | Therapist-generated, sagittal plane, nonweight-bearing mobilization |

Treatment plans based on patient response to repeated movements have been found to yield better results in symptom reduction, symptom elimination, and restoration of function when compared to other conservative interventions.28 In addition, when centralization is observed, a favorable treatment result is expected.25,27,29 Centralization is often seen when the injury is acute (less than 8 weeks), symptoms are intermittent, and the patient demonstrates no significant neurological deficits.16,29 Donelson et al. investigated the usefulness of the centralization phenomenon in evaluating and treating referred pain. It was determined that 87% of patients, in whom symptoms centralized, had excellent outcomes with relief of pain and functional recovery.25 If a directional preference is not found and symptoms do not centralize within 2–3 weeks, minimal improvements are expected and the risk of developing chronic disability is greater.24,26,29 It has been recommended that non-centralizers receive additional medical treatment for either physical or non-physical factors that could delay symptom resolution.26 Patients should also be instructed in performing an active exercise program emphasizing return to function and avoiding activities that increase or produce radicular pain.26

Manual therapy techniques

There are a variety of manual techniques utilized to treat cervical radiculopathy.16,22,23,55,56 Manual therapy may be used in an acute or stable condition. In the acute stage, gentle manual techniques are used to reduce pain and enable patients to begin movement on their own. In the latter stages of treatment, it is used to achieve and maintain full range of motion and function. Mobilization techniques are applied either actively or passively. Active mobilization includes proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and muscle energy techniques. Passive mobilization is a repetitive, passive movement of varying amplitude and low acceleration applied at different points in the range of motion.57

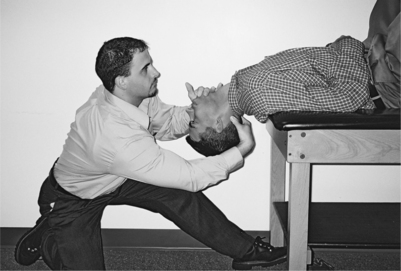

Manual techniques should begin with the spine positioned in a relatively pain free posture. A mobilizing force is locally applied to the designated vertebral segment. The direction of the mobilizing force is governed by patient response. In the presence of a radiculopathy, the exacerbation of distal symptoms should be avoided.58 The direction of application, the rate, the rhythm and the force used to produce motion and symptom changes must be meticulously monitored. Techniques can be individualized to appropriately treat the patient’s condition. The force of the mobilization will vary from very gentle and barely perceptible, in painful situations, to maximal force at end range of motion as symptoms become less irritable. As radicular symptoms decrease, treatment may be progressed to increase motion and resolve remaining axial pain. Figure 58.3 presents an end-range mobilization utilized to restore extension range of motion.

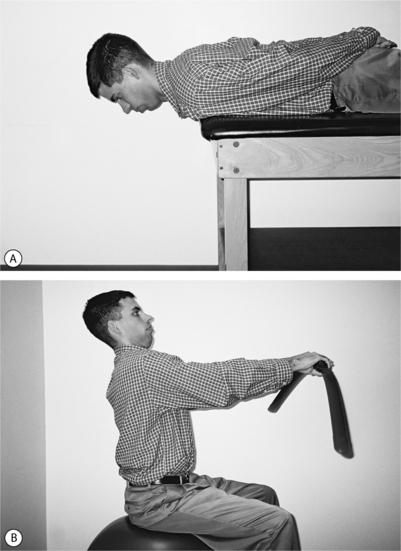

Neural mobilization techniques

Neural mobilization techniques are a combination of upper limb and cervical spine movements used to free nerve root restrictions and restore normal mobility to the nervous system.55 Refer to Figure 58.4 for an example of an upper limb nerve glide and stretch. These techniques are designed to stretch and glide the nerve root. This can be accomplished by performing upper limb neural tension tests. Neural mobilization techniques are applied either actively or passively. Because these techniques are designed to mobilize restricted neural elements, a temporary peripheralization of symptoms will occur. The production of peripheral symptoms should cease shortly after the treatment technique has been performed. Symptoms must not remain worse as a result of treatment. If the radicular symptoms remain exacerbated, the mobilization was applied too strenuously. In a patient in whom the radicular symptoms remain worse and cervical spine motion becomes limited in the opposite direction to the neural mobilization, the cervical spine movement, associated with the neural mobilization, could be aggravating the condition. The patient may have a directional preference and an underlying condition that will improve with repeated movements in that direction. Such a patient should be treated with repeated gentle movements until the symptoms are stable, and resume the neural mobilization techniques if a restriction still exists.16

When treating acute symptoms, the neural techniques should be performed passively, in a relaxed, pain relieving posture, far removed from the symptom area.55 The techniques are to be performed through as much of the range of motion as possible as long as symptoms are not reproduced. Butler and Jones recommend a sequence of gentle oscillations for approximately 20–30 seconds.55 After each sequence, symptoms must be monitored and reassessed. As the patient improves, pain free range of motion will improve. As this occurs, the treatments need to become more aggressive to have a therapeutic effect. Progression of the applied neural mobilization techniques may include: performing the technique actively, moving closer to or at the lesion site, placing tension on the neural system as the glides are being performed, increasing the grade of the mobilization and performing the oscillations at end range. Unlike treatment of the irritable condition, some degree of pain and symptom reproduction is expected and necessary to fully restore the neural movement. Symptoms must be constantly monitored to ensure that they are improving. The techniques are continued until full range of motion and function has been achieved.

The mechanism by which neural mobilization effectuates symptom resolution is unknown. The leading hypothesis is that ‘mobilization of the nervous system has a mechanical effect on the vascular dynamics, axonal transport systems and mechanical features of the nerve fibers and connective tissues.’55 Studies have been published that support this theory and the use of neural mobilization techniques for treating radicular pain.59–63 Although we are believers in this conceptual model and apply the techniques, there is no peer-reviewed literature that substantiates either the mechanism of action or that the treatment is effective.

Exercise

Once the patient’s symptoms have centralized, or if centralization has not occurred in approximately 2–3 weeks, restoration of function through an exercise program may begin.24,26,29 Care is taken to avoid production or exacerbation of radicular symptoms.26 Cervical spine stabilization techniques have been theorized to allow the patient to gain neuromuscular control over movements and eliminate mechanical sources of pain.6 The approach begins with identifying the neutral position of the spine. This neutral position is defined as the pain free position in which the patient can perform necessary functional activities. Starting in the neutral position, the patient is guided through a gradient of simple isometric exercises. Addition of upper limb and body movements can be incorporated to challenge the patient to maintain neutral cervical spine posture during simulated functional activities.64 Refer to Figure 58.5 for examples of cervical stability exercises. Patients are only progressed to more advanced positions when the basic exercises are pain free. Slow progression that is advanced as tolerated and focuses more on functional activities has been shown to yield better results.17 Others believe that the exercise should not be overly aggressive and efforts should focus toward progressively reducing the patient’s pain and advancing function.2 As the patient improves, strengthening may progress to isotonic or isokinetic techniques.

Ergonomics and patient education

Ergonomics is an essential adjunctive component of treatment. Many activities, both in the workplace and at home, require sustained positions that may compromise recovery and cause relapse.16,20,32 Activities requiring sustained positions tend to promote detrimental postures and increase radicular symptoms.16,32,55 Preventing sustained working postures is an integral aspect of the rehabilitation program.65 Appropriate work area design and body mechanics training should be performed to offer the patient the best possible chance of a maintaining recovery and function.

Patient education is one of the most important tools used to treat cervical radiculopathy. Patients instructed in the clinical reasoning process and given the proper education can competently begin self-treatment and help prevent future injuries.6,16 This training encourages the patient to become an active participant in the rehabilitation process. As a result, patients are able to evaluate their symptom response during activities and situations, utilize self-treatment techniques, and prevent recurrence.6,16,66 An appropriate quote by Mckenzie states, ‘If there is the slightest chance that patients can be educated in a method of treatment that enables them to reduce their own pain and disability using their own understanding and resources, they should receive that education.’16

In conclusion, the success of any physical therapy rehabilitative treatment plan begins with the evaluation. An effective evaluation utilizes signs and symptoms, identified during the history and physical examination, to govern clinical decision-making.16,17 The individualized treatment of cervical radiculopathy relies heavily upon clinical reasoning. There are no set techniques or predetermined protocols. Once the evaluation is complete, the clinician assesses the patient’s response and utilizes the algorithm to direct treatment. The algorithm provides a structured method of assessing patient symptoms and selecting an appropriate treatment pattern. Because the efficacy of any one treatment philosophy has not been firmly established, a variety of techniques, based on the patient’s response to movement testing, should be used to deliver the most comprehensive and effective treatment. The clinical approach also may vary depending on the acuity of the radicular pain and the etiology. Comorbidities and age are also taken into account when formulating a treatment plan including medication management and rehabilitation techniques. Communication with the patient and treating physician are integral parts of providing safe and effective treatment for patients with cervical radicular pain. Effective medication management including pain relief and reduction of inflammation are part of an effective rehabilitation program. They allow the physical therapist to progress treatment and contribute to the resolution of symptoms. Randomized, controlled trials evaluating rehabilitation techniques for the treatment of cervical radicular pain are necessary to better identify the techniques that are the most effective.

1 Heckmann JC, Lang CJ, Zobelein I, et al. Herniated cervical intervertebral discs with radiculopathy: an outcome study of conservatively or surgically treated patients. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:396-401.

2 Saal JS, Saal JA, Yurth EF. Nonoperative management of herniated cervical intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. Spine. 1996;21:1877-1883.

3 Sampath P, Bendebba M, Davis JD, et al. Outcome in patients with cervical radiculopathy: prospective, multicenter study with independent clinical review. Spine. 1999;21:591-597.

4 Persson LC, Moritz U, Brandt L. Cervical radiculopathy: pain, muscle weakness and sensory loss in patients with cervical radiculopathy treated with surgery, physiotherapy or cervical collar. A prospective, controlled study. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:256-266.

5 Persson LC, Carlsson CA, Carlsson JY. Long-lasting cervical radicular pain managed with surgery, physiotherapy, or a cervical collar: A prospective, randomized study. Spine. 1997;22:751-758.

6 Wolff MW, Levine LA. Cervical radiculopathies: conservative approaches to management. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2002;13:589-608.

7 Fouyas IP, Statham PF, Sandercock PA. Cochrane review on the role of surgery in cervical spondylitic radiculomyelopathy. Spine. 2002;27:736-747.

8 Ellenberg MR, Honet JC, Treanor WJ. Cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:342-352.

9 American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, 5th edn. Glenview, IL: APS, 2003.

10 Simdrup SH, Jensen TS. Efficacy of pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: an update and effect related to mechanism of drug action. Pain. 1999;83:389-400.

11 Backonja M, Glanzman RL. Gabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: evidence from randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2003;25:81-104.

12 Dillingham TR. Electrodiagnostic approach to patients with suspected radiculopathy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002;13:567-588.

13 Redford JB, Patel A. Orthotic devices in the management of spinal disorders. Spine: State of the Art Reviews. 1995;9:673-688.

14 Radhakrishnan K, Litchy WJ, O’Gallon WN, et al. Epidemiology of cervical radiculopathy: a population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, 1976 through 1990. Brain. 1994;117(Part 2):325-335.

15 Mochida K, Hiromichi K, Atsushi O, et al. Regression of cervical disc herniation observed on magnetic resonance images. Spine. 1998;23:990-995.

16 Mckenzie RA. The cervical and thoracic spine, 1st edn. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications (NZ) Limited, 1990.

17 Piva SR, Erhard RE, Al-Hugail M. Cervical radiculopathy: a case problem using a decision-making algorithm. JOBST. 2000;30(120):745-754.

18 Goebel A, Fater D, Kernozek T. The effects of cervical retraction exercise on forward head posture and cervical range of motion in an asymptomatic population. The Mckenzie Journal; 10:24–29.

19 Saunders DH, Saunders R. Evaluation, treatment and prevention of musculoskeletal disorders. Spine. 1993;3:1.

20 Braun BL. Postural differences between asymptomatic men and women and craniofacial patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:653-656.

21 Griegel-Morris P, Larson K, Mueller-Klaus K, et al. Incidence of common postural abnormalities in the cervical, shoulder and thoracic regions and their association with pain in two age groups of healthy subjects. Phys Ther. 1992;72:425-431.

22 Cyriax JH, Cyriax PJ. Cyriax’s illustrated manual of orthopaedic medicine, 2nd edn. London: OM Publications; Butterworth Heinemann, 1993.

23 Mulligan BR. Manual therapy ‘NAGS’, ‘SNAGS’, ‘MWMS’ etc, 4th edn. Wellington, New Zealand: Plane View Services, 1999.

24 Werneke M, Hart DL. Discriminant validity and relative precision for classifying pain patients with nonspecific neck and back pain by anatomic pain patterns. Spine. 2003;28(2):161-166.

25 Donelson R, Silva G, Murphy K. Centralization phenomenon: its usefulness in evaluating and treating referred pain. Spine. 1990;15:211-213.

26 Werneke MW, Hart DL, Cook D. A descriptive study of the centralization phenomenon: a prospective analysis. Spine. 1999;24:676-683.

27 Long AL. The centralization phenomenon: its usefulness as a predictor of outcomes in conservative treatment of chronic low back pain (a pilot study). Spine. 1995;20:2513-2521.

28 DiMaggio A, Mooney V. Conservative care for low back pain: What works? J Musculoskeletal Med. 1987;4:9.

29 Werneke MW, Hart DL. Centralization phenomenon as a prognostic factor for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1999;24:758-765.

30 Pearson ND, Walmsley RP. Trial into the effects of repeated neck retractions in normal subjects. Spine. 1995;20(11):1245-1251.

31 Scannell JP, McGill SM. Lumbar posture – should it, and can it be modified? A study of passive tissue stiffness and lumbar position during activities of daily living. Phys Ther. 2003;83(10):907-917.

32 Abdulwahab SS, Sabbahi M. Neck retractions, cervical root decompression, and radicular pain. J Ortop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:4-12.

33 Lentell G, Kruse M, et al. Dimensions of the cervical neural foramina in resting and retracted positions using magnetic resonance imaging. J Ortop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(8):380-390.

34 Michlovitz S. Thermal agents in rehabilitation. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

35 Hunter J, Mackin E, Callahan A, editors. Rehabilitation of the hand: surgery and therapy. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1995.

36 Fisher E, Solomon S. Physiological responses to heat and cold. In: Licht S, editor. Therapeutic heat and cold. Baltimore: Waverly Press, 1965.

37 Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders: A monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Spine. 1976;1:127-134.

38 Rosonoff H, et al. Chronic cervical pain: radiculopathy or brachialgia. Spine. 1992;17(suppl):S362.

39 Tan J, Nordin M. Role of physical therapy in the treatment of cervical disc disease. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23:435.

40 Harris PR. Review of literature and treatment guidelines. Phys Ther. 1977;57:910-915.

41 Colachis SC, Strohm BR. A study of tractive forces and angle of pull on vertebral interspaces in the cervical spine. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1965;46:820-829.

42 Colachis SC, Strohm BR. Relationship of traction time to varied tractive forces with constant angle of pull. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1965;46:815-819.

43 Stratton SA, Bryan JM. Dysfunction, evaluation and treatment of the cervical spine and thoracic inlet. In: Bonatell B, Wooden M, editors. Orthopaedic physical therapy. 2nd edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:77-122.

44 Hood J, Hart DL, Smith HG, et al. Comparison of electromyographic activity in normal lumbar sacrospinous musculature during continuous and intermittent pelvic traction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1981;2:137-141.

45 Murphy MJ. Effects of cervical traction on muscle activity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1991;13:220-225.

46 Colachis SC, Strohm BR. Effect of duration of intermittent cervical traction on vertebral seperation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;47:353-359.

47 Dreyer SJ, Boden SD. Nonoperative treatment of neck and arm pain. Spine. 1998;23:2746-2854.

48 Van der Heijden GJ, Beurskens AJ, Koes BW, et al. The efficiency of traction for neck and back pain, a systematic blinded review of randomized clinical trial methods. Phys Ther. 1995;75:93-104.

49 Zybergold RS, Piper MC. Cervical spine disorders: a comparison of three types of traction. Spine. 1985;10:857-871.

50 Deets D, Hands KL, Mupp SS. Cervical traction: a comparison of sitting and supine positions. Phys Ther. 1977;57:255-261.

51 Crue BL, Todd EM. The importance of flexion in cervical halter traction. Bull Los Angel Neuro Soc. 1965;30:95-98.

52 Judovich BD. Herniated cervical disc: a new form of traction therapy. Am J Surg. 1952;84:446-456.

53 Yates D. Indications and contraindications for spinal traction. Physiotherapy. 1972;58:55.

54 Esses SI. Textbook of spinal disorders. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company, 1995.

55 Butler DS, Jones MA. Mobilization of the nervous system. London: Longman Group UK Limited, 1991.

56 Maitland GD. Vertebral manipulation, 5th edn. London: Butterworth, 1986.

57 Gross AR, Kay TM, Dennedy C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the use of manipulation or mobilization in the treatment of adults with mechanical neck disorders. Man Ther. 2002;7(4):193-205.

58 Conley MS, Meyer RA, Bloomber JJ, et al. Noninvasive analysis of human neck muscle function. Spine. 1995;20(13):2505-2512.

59 Kornberg C, Lew P. The effect of stretching neural structures on grade I hamstring injuries. JOBST. 1989;June:481-487.

60 Bora FW, Richardson S, Black J. The biomechanical responses to tension in a peripheral nerve. J Hand Surg. 1980;5:21-25.

61 Korr IM. Neurochemical and neurotrophic consequences of nerve deformation. In Glasgow EF, et al, editors: Aspects of manipulative therapy, 2nd edn., Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

62 Lundborg G. Nerve injury and repair. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

63 Totten PA, Hunter JM. Therapeutic techniques to enhance nerve gliding in thoracic outlet syndrome and carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 1991;7(3):505-520.

64 Cordo PJ, Nashner LM. Properties of postural adjustments associated with rapid arm movements. J Neurophysiol. 1982;47(2):287-302.

65 Jacobs K, Bettencourt CM. Ergonomics for therapists. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1995;140-141.

66 Slipman CW, Isaac Z, Patel R, et al. Chronic neck pain: the specific syndromes. J Musculo Med. 2003:24-33.