CHAPTER 100 Surgical Management of Isthmic, Dysplastic and Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

INTRODUCTION

Spondylolisthesis is a common radiological and clinical condition that may arise as a result of different developmental and pathological processes. Although the classification system proposed by Wiltse, Newman, and McNab is the most widely accepted1 there is no consensus which classification system is the most appropriate for clinical decision-making.1–3 Most authorities agree that the presence or absence of an isthmic defect or elongated pars in conjunction with the presence or absences of dysplastic changes are the most important features of any classification system.2,3 Some types of spondylolisthesis occur only in adults (i.e. degenerative), while others are encountered mostly in children and adolescents (dysplastic). Although isthmic spondylolisthesis is present in both children and adolescents as well as in adults, the clinical presentation and natural history of this type of spondylolisthesis differ in the two age groups. It is obvious, therefore, that the recommended management of isthmic spondylolisthesis in adolescents may differ from the desirable management in adults.

Some types of spondylolisthesis require simple and standard surgical management, others require the most complex and challenging surgery. Many reports on the surgical management of spondylolisthesis lump together different types of spondylolisthesis, different age groups, and are at best anecdotal and retrospective. Only a few well-conducted outcome studies4–6 on the surgical management of spondylolisthesis have been published on well-defined populations with similar types of vertebral slip (isthmic or degenerative). It is not surprising, therefore, that the surgical management of the various types of spondylolisthesis is not yet standardized and depends among other factors on the severity of the slip. Therefore, the type and extent of the surgical management is often controversial. This controversy is well reflected in the literature.7

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

Adolescents

Wiltse and Jackson8 outlined the guidelines for the management of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children. Failure of adequate conservative management (discussed in the previous chapter), may dictate the need for surgical intervention, including surgical stabilization.9 In general, most low-grade isthmic slips are managed successfully with nonoperative treatment and only one-third of patients will require surgery.10 Adolescents and young adults with spondylolysis may be managed with pars interarticularis repair. Surgical stabilization should be strongly considered, in symptomatic adolescents with slips between 25% and 50%, and in asymptomatic individuals in whom slip progression is documented radiologically. Surgical stabilization is mandatory in slips greater than 50%, or when the slip angle exceeds 45 degrees, even in the absence of symptoms, as further slip progression will certainly occur.8,11,12

Adults

In adults with low back pain and/or sciatica, the mere presence of spondylolysis or minimal olisthesis is not by itself an indication for surgery. Symptoms may not be directly related to these abnormalities, which probably developed many years prior to the current complaint. The cause of pain may be the result of a lesion elsewhere in the spine. Nevertheless, after the fourth decade of life some adults with a mild slip present with back and leg pain, due to superimposed degenerative changes either at the slip level or at the level above the spondylolisthesis. In addition, adult slip progression secondary to the degeneration of the disc at the slip level may occur in up to 20% of adults with low-grade isthmic slip.13 If conservative measures fail to control low back and or leg pain, operative treatment may be indicated.4,14

OPTIONS FOR SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

In general, the surgical options in the management of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are as follows: pars repair, neural decompression without or with stabilization, and fusion (without or with decompression). Spinal fusion can be approached with various techniques: (1) posterolateral in situ fusion with or without instrumentation, (2) circumferential in situ fusion (anterior interbody or posterior interbody fusion), (3) slip reduction and posterolateral fusion or circumferential procedures with or without sacral dome resection, and (4) in spondyloptosis slip reduction or L5 excision and fusion of L4 to the sacrum.

Spondylolysis: pars repair

A direct repair of a pars defect, which is in essence a stress fracture, is a logical operative solution in patients with symptomatic spondylolysis. Repair of the pars restores normal anatomy, without loss of segmental motion, and does not require an extensive surgery since fusion is avoided.15 It may also reduce mechanical stress on the adjacent spinal levels. A prerequisite for the procedure is the presence of a type IIA pars defect1 and a nondysplastic posterior arch, together with a normal disc and facet joints at the involved level. To better delineate which patients are suitable candidates for pars repair, lidocaine infiltration of the pars under fluoroscopy may be helpful. Postinjection pain relief and the presence of a pars defect smaller than 7 mm, are the best predictors for clinical success of this surgical procedure.15,16 Pars repair can also be considered in individuals with a minimal slip without disc degeneration.

There are several operative methods available to achieve this goal. The most commonly used techniques are Buck’s screw fixation,17 Scott’s transverse process wiring,18 or Morscher’s hook screw device.19 Biomechanical testing has demonstrated that pars screws or devices that rely on pedicle screw fixation provide better mechanical stability and minimize stress across the pars defect.20 In all pars repair techniques the need to excise the pars pseudoarthrosis, freshen the bone edges, and to apply locally cancellous bone graft is of utmost importance. A brace is worn after surgery for at least 8–12 weeks.

Bradford and Iza18 reported on their experience with the Scott’s wiring technique in 22 patients. They found that the clinical outcome of the Scott’s wiring was favorable in 80% of the patients, and 90% obtained a pars defect fusion. Johnson and Thompson21 found that the clinical outcome of the Scott’s wiring was favorable in individuals with spondylolysis younger than 25 years of age. Buck reported on his experience with the Buck screw in 75 patients. The surgical outcome was good in 88%.17 Hefti et al.19 reported on their experience with the Morscher hook screw technique for direct repair of the pars in 33 patients. Pain relief was attained in 79% of patients and a healed pars was observed in 73%. The largest series of patients with pars repair published to date included 113 individuals who underwent pars repair with the Morscher device and were followed for an average of 11 years.16 Union of the pars defect was achieved in 87%. Pseudoarthrosis rates were found to be four times higher in patients older than 20.16

Decompression in isthmic and dysplastic spondylolisthesis

When radicular pain, as opposed to back pain, is the main complain of the patient, even in the absence of neurological deficit, neural decompression may be in indicated. Gill22 suggested removing the loose posterior elements and the fibrocartilagenous pars defect in order to decompress the neural elements without performing arthrodesis, and argued that this was the management of choice for symptomatic spondylolisthesis. He indeed published a report of a series of patients in whom pain alleviation was achieved with laminectomy alone, without arthrodesis. However, when one considers that spondylolisthesis is by definition an unstable condition, surgical damage to the posterior ligamentous structures by performing a laminectomy will render the spine even more unstable. Indeed, Gill himself noted some increase in the amount of vertebral slip in about 40% of his patients. Others have documented a more pronounced postoperative slip progression following laminectomy without fusion, not only in children and adolescents but also in young adults under the age of 40.8,11,23,24 Gill’s laminectomy, when performed alone, is mentioned only to be condemned, especially in children and adolescents. Carragee considers it futile performing decompressive laminectomy in adults with mild isthmic slip without neurological signs as it does not improve the clinical outcome and may increase the rate of pseudoarthrosis following noninstrumented spondylodesis.5 Combining decompressive laminectomy with pedicular screw fixation will provide better clinical results.5 Carragee’s experience echoes earlier reports that decompression is not always mandatory in patients with radicular pain. Posterolateral fusion alone will often eliminate radicular symptoms.25,26 The absolute indications for decompression in spondylolisthesis are: symptomatic radiculopathy with motor deficit, or sphincteric involvement.

Posterolateral in situ fusion

In low-grade olisthesis

For more than five decades in situ posterolateral fusion with iliac crest bone graft was the most commonly applied surgical procedure for low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis and is considered even today as the gold standard, especially in children and adolescents.24 Although anatomical reduction of the slip may be desirable, restoration of function with minimal risk to the patient is the ultimate goal of surgery in spondylolisthesis. In low-grade slips in situ arthrodesis carries a minimal risk, and leads to good or excellent clinical results in most patients. Reports on the successes of in situ posterolateral monosegmental fusion with or without Gill’s decompression date back to the late 1950s and early 1960s.27,28 Two retrospective studies reviewed almost 300 patients, and reported greater than 80% fusion rates and a clinically asymptomatic postoperative result.27,28

Wiltse and Jackson8 popularized the paraspinal approach for in situ arthrodesis. The procedure is carried out through a midline skin incision, followed by bilateral incision of the thoracolumbar fascia and bilateral muscle splitting through the sacrospinalis with exposure of the lateral gutters and the transverse processes. Arthrodesis extends from the transverse processes of L5 to the sacral alae. Autologous iliac crest bone graft is laid down. The results of in situ fusion are good to excellent in most cases with fusion rates of 68–100%.8,29–31 Postoperative management may include cast or brace immobilization, although many surgeons do not apply postoperative immobilization at all.8,31 Postoperative immobilization may be recommended if decompression was performed in addition to the spondylodesis or in patients with slips greater than Meyerding 2. Decompression should be performed in conjunction with arthrodesis whenever a focal neural deficit correlating with the spinal imaging is present.11 It was already noted that some surgeons8,25,26 do not perform decompression in conjunction with arthrodesis in both adolescents and adults, as in situ fusion alone was found to eliminate neurologic symptoms.

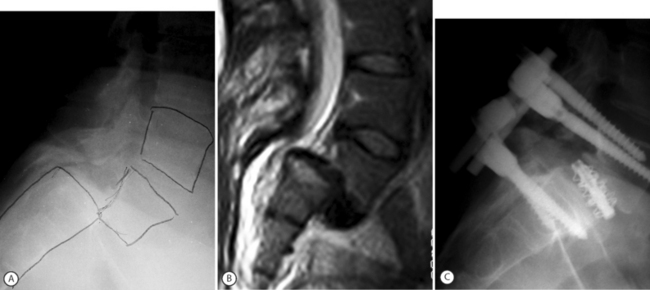

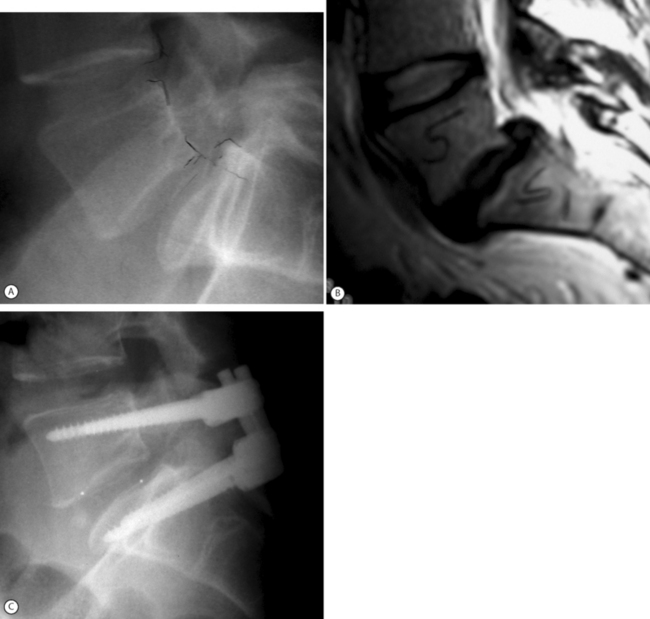

In general, the results obtained in adults with in situ fusion are not as good as in children and adolescents,32–34 not only because of the associated degenerative changes which may be present above and at the slip level, but also due to smoking status and workmen’s compensation claims.33 Haraldsson and Wilner34 conducted a comparative study of posterolateral fusion in adolescents and adults and noted that only 57% of adults with a lumbosacral slip who underwent fusion had a good clinical result as opposed to the 95% successes rate obtained in children and adolescents. In contrast to the different clinical outcome observed in the two groups, fusion rates approached 100% in both adolescents and adults.34 More recently, and in considerable contrast to the last three cited reports,32–34 Moller and Hedlund4 reported a high success rate of in situ fusion in adults with low-grade slips. One hundred and eleven patients were randomly allocated to either an exercise program or posterolateral fusion. At a minimum 2-year follow-up, patients subjected to surgical fusion had statistically superior results on both the Disability Rating Index and the visual analog scale.4 Moller and Hedlund4 concluded that posterolateral fusion is a method supported by evidence-based medicine standards to reduce back pain and functional disability in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. They also reported that the results of noninstrumented fusion were as good as those attained with instrumentation14 The clinical results obtained by Moller and Hedlund are even more striking since Gill’s decompression was carried out in two-thirds of the patients (all with sciatic pain) in both the noninstrumented and instrumented groups (personal communication). This author’s own personal experience with decompression and fusion in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis is similar.35 Between January 1999 and July 2003, 25 consecutive adults with symptomatic lumbosacral isthmic slip (average age 50 years) underwent surgery for slips ranging from grade 1 to 4. All cases had a Gill procedure, instrumentation, and posterolateral fusion (Fig. 100.1).35 Back and leg pain relief was achieved in all with radiological evidence of solid fusion. The results of fusion surgery in adults with isthmic spondylolisthesis are certainly better than those observed in adults undergoing fusion for purely degenerative disc disease.36 The combination of mechanical instability associated with spondylolisthesis, compounded by the development of degenerative changes with or without neural compression, will respond more favorably to spondylodesis.13

In high-grade olisthesis

In situ fusion is not only efficient in low-grade olisthesis but also in patients with high-grade slips. Because the transverse process of L5 may be dysplastic and small and lies too deep to be accessed, in situ fusion of high-grade slips may extend from the ala to the transverse process of L4. Postoperative immobilization in high-grade slips is mandatory. Casting or bracing with thigh extension (in one leg) should be instituted for a least 2–3 months. Johnson and Kirwan37 collected 17 patients with slips greater than 50% managed by in situ fusion. Sixteen of the 17 patients had a good clinical result. Reynolds and Wiltse published a similar-sized series and similar success rate.38 No change was observed in the degree of slip or sagittal rotation at the final follow-up X-ray.38 These authors noticed that with the attainment of a solid fusion (approximately 7 months postoperatively), pain, hamstring tightness, overall cosmetic appearance, and posture were improved. Peek et al.25 reviewed eight adults with grade 3 and 4 slips, who were managed by in situ fusion without decompression. Again, good results were recorded in all patients, including resolution of neural deficits, even though no neural decompression was performed. Boxall et al. also reported that pain, gait abnormalities, hamstring tightness, and neural deficit all resolve with in situ fusion without concomitant decompression.12 Seitsalo et al.39 collected 93 adolescents (mean age 14.8 years) who underwent surgery for high-grade spondylolisthesis with long-term follow-up. Ninety-four percent of the patients obtained satisfactory clinical results with in situ fusion only. Another study from the same institution found that in situ fusion results in adolescents compared favorably with the results of surgical slip reduction accompanied by both anterior and posterior fusion; however, in the latter group postoperative complications were more common.40

Drawbacks of in situ fusion in high-grade slips

Despite the impressive excellent functional results obtained with bilateral lateral in situ fusion, there are several drawbacks with this technique when managing high-grade slips. In high-grade slips, the fusion mass is subjected to tension, flexion, and shearing forces. Attaining a solid fusion can be endangered by repetitive stress fractures in the fusion mass leading to gradual slip progression. Indeed, some authors report a high incidence of pseudoarthrosis (up to 45%) in patients with high-grade slips undergoing in situ arthrodesis.11,12,39,41–43 In addition, an increase in the slip angle (15–20 degrees) and the degree of slip (up to 33% increase) were noted as well despite an apparently solid fusion mass.12,41,42 Slip progression was found to occur in the first 6 months after surgery. Although in situ fusion is considered a simple and safe surgical technique, neural injury is possible. Schoenecker et al.44 collected 189 patients who underwent in situ fusion for high-grade slip at several major US spine centers. Twelve of them (6%) developed cauda equina symptoms following in situ fusion. In less than 50% of these patients did the cauda equina injury recover. Patients at risk for developing postoperative cauda equina dysfunction were those with slip angles greater than 45 degrees. Schoenecker44 postulated that the cauda equina injury was probably the result of intraoperative slip progression that occurred due to loss of muscle protection during anesthesia as well as the surgical destabilizing effect. Radiculopathy of the first two sacral roots is common before surgery in many patients with high-grade slips. This is explained by the fact that the S1 and S2 roots tent over the vertical sacrum. In addition, in many of the patients there is also evidence for L5 radiculopathy. The likelihood for intraoperative neural injury in high-grade slips is thus compounded.

Slip reduction

The advantages of slip reduction in conjunction with arthrodesis are numerous and include: improved spine biomechanics, better nerve root decompression (usually by an indirect effect of the reduction), better opportunity to obtain fusion as the fusion is no longer under the influence of tension and anterior shear forces, improved posture, and better cosmetic appearance.45 As well, reduction is associated with less postoperative slip progression. Reduction of the angular deformity is probably more important than reduction of the translational deformity since the angular roll is the main factor leading to lumbosacral kyphosis.

Closed reduction

Although the initial attempts at closed reduction of spondylolisthesis date back to the 1920s 1930s, Scaglietti et al.46 should be credited for popularizing the practice of closed reduction of spondylolisthesis. Other strong proponents of closed reduction are Marchetti and Bartolozzi.2 Closed reduction is reserved mainly for children and adolescents. A closed reduction may be accomplished by longitudinal traction on a Risser or Cotrel table, combined with pelvic and hip extension. Reduction is done while the patient is awake, achieved gradually, and is followed by immobilization in a bilateral hip spica. Bilateral lateral fusion is then performed in the reduced position through a window in the cast. The patient is kept recumbent for 3 months following reduction and spondylodesis. Scaglietti et al.46 reported a 50% reduction of the slip grade as well as a decrease in the slip angle. Several series of cast reduction and fusion were published.41,47–51 Bradford reported that posterolateral fusion and cast reduction decreased the average preoperative slip angle of 33 degrees by two-thirds.49 Two of the 22 patients developed a transient L5 weakness (both were also managed by skeletal traction).49 Bradford and Boachie-Adjei later reported on a modification where posterior decompression, sacral dome osteotomy, and L4–S1 fusion were followed by closed reduction with halo skeletal traction and anterior strut grafting.50 Burkus et al.51 advocated the performance of bilateral lateral fusion and decompression, if necessary, followed by gradual cast reduction. Burkus et al. reported the long-term results of in situ arthrodesis combined with closed reduction and compared them to the results obtained with in situ fusion without reduction.51 Out of 42 adolescents reported, 24 were fused in situ and then reduced in a cast, while the other 18 underwent posterolateral fusion without reduction. Although in most cases where closed reduction was attempted some correction of translation and slip angle was achieved, clinical results were similar in both groups of patients. However, patients who underwent reduction had less late progression of the deformity, less sagittal translation, a smaller lumbosacral kyphosis, and a lower incidence of pseudoarthrosis.

Pedicle screw fixation and reduction of spondylolisthesis

Modern internal fixation of the spine is based on pedicle screw fixation. Pedicle screws impart excellent control and fixation of all 3 columns of the spine and allow efficient slip reduction together with restoration of sagittal alignment and stabilization of the spine in the corrected position. In addition, pedicle screw fixation may also enhance the rate of fusion.52 Pedicle screws alone may provide for instrumented reduction in a ‘supple’ slip by way of rod or plate contouring into the desired lordosis. In more stiff deformities, screw–bolt reduction devices such as the SOCON spondylolisthesis reduction apparatus provide for further slip reduction (Fig. 100.2). This assembly enables posterior translation of the slipped vertebra and the levered forces are applied to both L5 and S1 vertebrae. Matthiass and Heine were the first to popularize a slip reduction device although Schollner was the originator of the technique.53 Matthiass and Heine performed L5–S1 discectomy with sacral dome resection when necessary, manual levered reduction of L5 combined with posterior translation by means of the screw-bolt–sacral plate and posterolateral arthrodesis. Almost 46% of the patients without preoperative neurologic deficit developed postoperative motor deficits, mostly transitory.53 Steffee and Sitkowski employed a similar technique and combined both screw-bolt reduction with the VSP plate as well as levered reduction by means of a ‘persuader.’54 Ten percent of patients developed transient L5 radiculopathy.55 Other series reported an even higher rate of L5 root lesions.56 Why is L5 nerve root injury common during slip reduction of high-grade olisthesis? Petraco et al. studied the relationship of the L5 root and the degree of vertebral slip in an in vitro model.57 They found that the risk of stretch injury to the L5 nerve during reduction of a high-grade slip was not linear, with 71% of the total strain in the nerve occurring during the second half of the reduction. They concluded that partial reduction was safer than complete reduction and that correction of the lumbosacral kyphosis had a protective effect on the L5 nerve.57 In his ‘point of view’ relating to the Petraco study, Hensinger wrote: ‘Spine surgeons should temper their enthusiasm for obtaining complete reduction, which is esthetically more pleasing but may significantly increase the neurological risk to the patient.’58 During the process of reduction, the L5 nerve root may also be entrapped outside the spinal canal when it passes underneath the lumbosacral/iliolumbar ligamentous complex.59 In high-grade slips it is also possible to injure proximal lumbar roots, as considerable acute lengthening of the spine occurs during slip reduction.60 A few important points must be emphasized whenever reduction of high-grade slips is considered: (1) the patient should be positioned on the operating table with flexed knees to relax the sciatic nerve; (2) it is sometimes necessary to keep the knees flexed for about a week after surgery; (3) it is important, when feasible, to monitor the L5 and S1 roots during surgery; (4) sacral screws should have a bicortical purchase; (5) consider screw purchase at S2 or, alternatively, iliac screws;43 and (6) consider Jackson’s intrasacral fixation to enhance the biomechanical strength of the construct.61

Despite the numerous advantages of pedicle screw fixation, pedicle screw-based slip reduction remains controversial because it is associated with a considerable rate of surgical complications.7 Thus, there are legitimate arguments for both slip reduction and in situ fusion. The high percentage of neural complications reported with instrumented slip reduction led Bradford to the conclusion that: ‘instrumented reduction cannot be regarded as a routine method for treating spondylolisthesis … since there are alternative less risky procedures with satisfying clinical results.’7 Poussa et al.40 compared two groups of adolescents with severe slips managed operatively. One group underwent instrumented reduction and fusion while the other group underwent in situ fusion. Although both groups achieved the same functional and clinical results, the reduction group had more complications and reoperations.

Anterior-posterior resection reduction (staged or combined)

Early attempts at slip reduction, especially those of high-grade slips, led to the conclusion that anterior surgery was necessary for both release and to ensure a solid fusion. Staged or combined procedures are reserved almost exclusively for high-grade slips. In the anterior procedure, anterior discectomy and release, partial sacrectomy if needed, and anterior arthrodesis are performed. Two weeks later, Gill’s laminectomy and levered reduction with internal fixation and fusion are performed.62 Postoperative immobilization should be considered in order to achieve fusion and a good clinical result. The sequence of anterior and posterior surgical interventions is variable among surgeons.62 Many authors have utilized traction either preoperative, between the staged procedures, or after surgery, in the form of 90–90 traction, halo-femoral traction or halo-pelvic traction to facilitate slip reduction.41,48,50,63

Balderston and Bradford,48 for example, combined both spinous process traction wires that were connected to an outrigger and halo pelvic traction. More recently, Bradford and Boachie-Adjei50 reported on the long-term follow-up of spondylolisthesis managed by anteroposterior resection reduction. Although the slip angle was reduced from 71 degrees to 31degrees, the percentage of slip was not changed appreciably following surgery. Three of the 22 patients in the report developed new neural deficits, although nine of the 10 patients with preoperative neural sequelae improved following surgery. O’Brien et al.63 reported similar results following the latter type of procedure. Most of the series reporting on staged procedures found a high incidence of neural complications in up to 25% of patients.41,55,56,64

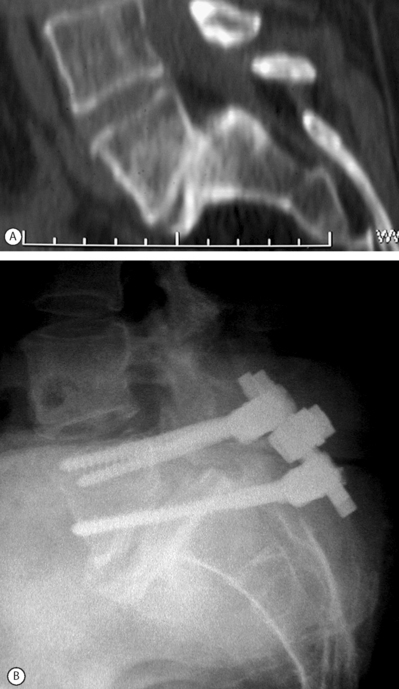

Gradual instrumented reduction

To overcome the alarming incidence of neural complications associated with pedicle screw slip reduction, Edwards developed and refined the concept and the technique of gradual instrumented reduction of spondylolisthesis.45 Edwards claims that gradual reduction is possible by simultaneous application of three corrective forces: distraction, posterior translation, and lumbosacral extension. It is important to have a two-point sacral fixation (at S1 and S2) during the reduction maneuver to withstand the considerable forces needed for reduction and restoration of sagittal alignment. The viscoelastic stress relaxation of the soft tissues during gradual reduction enables stretching of the anterior contracted nonosseous structures. In addition, Edwards claims that the restoration of full anatomical alignment obviates the need for interbody grafting. Others disagree with the latter statement and would recommend a TLIF or PLIF whenever possible (Fig. 100.3).56,65,66 According to Edwards,45 the main indications for gradual slip reduction are: (1) sacral root irritation leading to symptoms of impaired bowel and bladder control; (2) a progressive slip greater than 50%; (3) major trunk deformity with sagittal decompensation; and (4) pain or neural deficit combined with two or more risk factors such as a large slip angle, a trapezoid L5, a rounded sacrum, female adolescent and symptoms of sacral nerve root stretching. It must be stressed that gradual slip reduction should be reserved for a small, selected group of patients because even in the best hands reduction of high-grade slips is associated with a substantial complication rate.7

With this technique, Edwards was able to achieve the following results in a group of 18 patients with high-grade slips: 91% correction of the slip was realized, the final lumbosacral kyphosis was reduced to 4 degrees, and a solid fusion was obtained in 94% of the patients. Slip reduction resulted in an average of 32 mm of trunk height gain. There was a 5% incidence of transient unilateral L5 nerve root weakness.45 Hu and associates reported their experience with the Edwards gradual slip reduction in 16 patients with a high-grade slip.64 The average preoperative slip was reduced from 89% to 29% and the slip angle was reduced from 50 degrees to 24 degrees. Three patients had neurologic impairment postoperatively (19%); one did not resolve. Four patients had hardware failure (25%). Ten patients had an excellent result, five patients had a good result, and one patient had a fair result.64

Spondyloptosis

In spondyloptosis, the lumbar spine slips completely off the sacrum and the inferior endplate of L5 rests facing the anterior part of the sacrum. The loss of sacral support appears to be the most significant difference between high-grade spondylolisthesis and spondyloptosis.45 Attempts at spine fusion without reduction in spondyloptosis usually result in loss of fixation and nonunion.47 Therefore, there is a need for reduction in spondyloptosis.45 (Reduction of spondyloptosis is associated with considerable lengthening of the spine, which will result in significant stretching of the lumbar roots.) According to Edwards,45 reduction of spondyloptosis is feasible if only up to 3–5 cm of lengthening of the course of the lumbar roots is anticipated. More lengthening is not tolerated without loss of neural function. Additional contraindications for reduction are: a slip angle of 50 degrees or more, rigid lumbar lordosis, long duration of the ptosis, age 20 or older, or previous attempts at fusion. In such cases, resection of the sacral dome and the lower part of L5 may provide an additional 3 cm of possible lengthening during reduction.45 Nerve root monitoring and a wake-up test are important adjuncts to the technique. Initially, temporary rods from the ala to L1 are placed. Wires are attached to the lumbar pedicle screws and connected to a traction bridge hanging over the operation table. The wires are attached to weights to initiate posterior translation. A laminectomy, L5–S1discectomy, and sacral dome osteotomy are performed. Gradual reduction is then started, approximately 1 hour per slip grade. Following reduction, L4–S1 fixation is performed with posterolateral fusion. Edwards’s results of ptosis reduction were as follows: 88% slip reduction, preoperative kyphosis reduced from 36 degrees kyphosis to 23 degrees lordosis (a 59 degree correction) and a 25% neural complication rate, mostly unilateral L5 nerve root lesions.45

Vertebrectomy of L5 (Gaines procedure)

Another way the tackle the problem of spondyloptosis is by a ‘shortening’ procedure that is accomplished by resection of the L5 body. Huizenga67 and Gaines and Nichols68 were the first in the English literature to describe L5 resection and L4–S1 fusion in spondyloptosis. The Gaines procedure consists of two stages. First, the lumbosacral junction is approached retroperitoneally or transperotoneally. The L5 body is resected to the base of the pedicles together with the two adjacent discs (L5–S1, L4–5). In the second stage (performed either under the same anesthesia or after 2 weeks), a midline posterior approach is undertaken through which the lamina and pedicles of L5 are removed, L4 is reduced onto the sacrum, and pedicle instrumentaion of L4–S1 is performed with bone-on-bone fusion or with an intervening interbody cage. Postoperative brace immobilization is recommended.69 Even this ‘shortening’ procedure is associated with an enormous incidence of iatrogenic neural deficit – 75%!69

Jackson’s sacral fixation technique

The sacrum serves as the foundation of every lumbosacral fixation. Jackson61 pointed out four reasons why sacral fixation may by troublesome: (1) difficult local anatomy; (2) poor bone quality frequently encountered in the sacrum, even in nonosteopenic individuals; (3) the posterior position of the implants with respect to the center of gravity and the axes of spinal angulation in the sagittal plane; and (4) large lumbosacral loads exerting flexural bending moments and cantilever pull-out forces. Jackson61 developed a new concept of sacral instrumentation. He uses sacral screws with closed oblique canals and strong ductile rods. The rod, which is introduced through the oblique canal sacral screw, is driven into the sacrum itself more distally. This creates the so-called ‘sacroiliac buttress’ and allows the instrumentation to be fixed to the anterior sacrum, resisting the posterior pull-out forces. In situ contouring allows for effective reduction of the slip.

Alternative methods

Bohlman’s fibular dowel technique

Smith and Bohlman70 reported yet another variation of lumbosacral fixation. They performed posterior decompression, posterolateral arthrodesis from L4 to S1, as well as inserting a fibular graft that was passed from the back of S1 through the L5–S1 disc and into the L5 body. They performed this procedure on 11 patients, most of them adults with high-grade slips accompanied by neurologic deficit including cauda equina syndrome. Utilizing this technique through a single posterior approach, they achieved a 100% fusion rate and resolution of neural deficit. Esses et al.71 and also Roca et al.72 utilized the same technique with equally successful fusion rates and clinical improvement.

Trans-sacral transvertebral interbody fixation

The spondylolisthetic deformity is fixed in situ by advancing the S1 pedicle screw through superior sacral endplate through the L5–S1 disc and into the L5 body.73 This fixation provides immediate three-column fixation of the lumbosacral junction. It is a good method for salvage of failed spondylolisthesis fusion or in cases with advanced disc degeneration at the slip level where reduction is not feasible or contraindicated (Fig. 100.4). This technique may allow partial reduction to be combined with trans-sacral interbody fixation.74,75

In conclusion

In situ fusion without instrumentation is the treatment of choice in children and adolescents with grade 1–2 spondylolisthesis although pedicle screw fixation may obviate the need for postoperative bracing. In adults with mild to moderate olisthesis with disc degeneration at the slip level, the adjacent cephalad disc should be investigated, including the performance of provocative discography. If it is found to be a pain generator it should be incorporated in the spondylodesis. The role of anterior column support in adults with low-grade slips has not been established. Patients with mild to moderate slips with marked disc space narrowing should be managed with posterior decompression, pedicle screw instrumentation, and posterolateral fusion (Fig. 100.5). Patients with spondylolisthesis with a relatively preserved disc space height or patients undergoing slip reduction should probably be subjected to posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF or TLIF) in addition to posterolateral fusion and pedicle screw fixation. Patients with advanced slip accompanied by advanced degenerative changes should undergo decompression with transacral interbody screw fixation ending in the L5 body. Posterior instrumentation should be attempted in all grade 3–4 supple slips. If a good correction of the lumbosacral kyphosis is obtained, fixation from L5 to the sacrum is sufficient, provided that TLIF or PLIF are performed. Posterior grafting with extension cast reduction is feasible in young patients with a flexible deformity that exceeds grade 4 slippage. Anteroposterior resection reduction should be reserved for stiff deformities, such as autofusion in high-grade slips. The procedure usually entails anterior resection, release and interbody fusion followed 2 weeks later by laminectomy, posterior dome osteotomy, and reduction by instrumentation. The procedure entails considerable incidence of complications: up to 30% root deficit and up to 25% nonunion. It must be stressed that treatment of severe slippage continuous to pose a therapeutic challenge and that instrumented reduction is at best controversial.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis

Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis usually present with symptoms after the fourth or fifth decade of life. There is a female preponderance, the condition is more common in patients with diabetes mellitus, and the prevalence of the condition increases with age.76 The condition arises secondary to disc and facet joint degeneration. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is not a pure translatory deformity but rather a rotatory subluxation.77 As such, the slip does not exceed 30% of the width of the vertebra below. Only after decompressive surgery without spondylodesis may the slip exceed 50% and rarely even more. The most common symptoms leading to operative intervention are severe spinal claudication or sciatica accompanied by mild low back and buttock pain unresponsive to medical rehabilitation and interventional spine care. Occasionally, a foot-drop or signs of cauda equina compression are the presenting symptoms leading to surgical intervention.

The main goal of surgery is to decompress the stenotic canal associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis. By performing decompression of the neural elements, relief of sciatica and/or neurogenic claudication is expected. Pedicle-to-pedicle decompression has been advocated. The extent of facet resection has been debated from preservation of the facets to partial facet resection or to complete excision of the posterior joints.76 Frequently, during decompression 50% of the facets are sacrificed or the pars interarticularis is breached. The disc should be left intact unless a frank extrusion is noted. The main problem with decompressive surgery in degenerative spondylolisthesis is the occurrence of postoperatvie slip progression. Slip progression following surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis is a common occurrence and may be associated with a bad clinical result.78 Progression can occur even when concomitant arthrodesis without instrumentation has been performed.79 Preoperative radiographic and anatomical risk factors associated with the postoperative development of slip progression include a well-maintained disc height, the absence of degenerative osteophytes, and sagittally oriented facet joints.80 Because postoperative slip progression is associated with a mediocre clinical outcome, arthrodesis should be considered. The role of arthrodesis in the operative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with associated degenerative spondylolisthesis has been the subject of much discussion. Laus et al. reported clinical success after decompression alone in a group of patients who had degenerative spondylolisthesis with spontaneous ‘stabilization’ of the pathological segment by spondylotic osteophytes.81 Others also advocated decompressive surgery alone.82 Herkowitz and Kurz,6 in 1991, published a prospective, randomized study comparing the clinical results obtained with decompression alone and with decompression and intertransverse fusion. Fifty consecutive patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis were randomly assigned to one of the treatment groups. Follow-up averaged 3 years. Herkowitz and Kurz found a significantly better clinical outcome in patients who underwent arthrodesis in addition to decompression. Although 36% of the patients did not achieve a solid fusion, good clinical outcome was possible in the presence of pseudoarthrosis. Fishgrund et al.83 in a prospective, randomized study in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis compared the results of decompression and noninstrumented fusion to those with instrumented arthrodesis. Although the rate of pseudoarthrosis was 55% in the noninstrumented group, compared to only 17% in the instrumented group, the clinical results were the similar. Fishgrund et al. concluded that the fusion status did not affect the clinical outcome.83 More recently, however, Kornblum et al.84 in a long-term follow-up study (5–14 years, 92 months on average) found that by obtaining a solid fusion a statistically significant better clinical outcome was achieved in patients operated on for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Eighty-six percent of those with a solid fusion had a good to excellent outcome as compared to only 56% of patients with a pseudoarthrosis. There is enough evidence in the literature to advocate the use of instrumentation to ascertain a higher fusion rate.52,79 Indeed, Booth et al. reported on a 100% fusion rate in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis managed by decompression and instrumented fusion. After 5 years, 85% of the patients who had a solid fusion maintained a satisfactory clinical outcome.85

1 Wiltse LL, Newman PH, McNab I. Classification of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:23-29.

2 Marchetti PG, Bartolozzi P. Classification of spondylolisthesis as a guideline for treatment. In: Bridwell KH, DeWald RL, editors. Textbook of spinal surgery. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:1211-1254.

3 Hammemberg KW. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. In: DeWald RL, editor. Spinal deformities. A comprehensive text. New York, Stuttgart: Thieme; 2003:787.

4 Moller H, Hedlund R. Surgery versus conservative management in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. A prospective randomized study: Part 1. Spine. 2000;25:1711-1715.

5 Carragee EJ. Single-level posterolateral fusion, with or without posterior decompression, for the treatment of isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79:1175-1180.

6 Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1991;73:802-808.

7 Edwards CC, Bradford DS. Controversies. Instrumented reduction of spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1994;19:1535-1537.

8 Wiltse LL, Jackson W. Treatment of spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis in children. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:92-100.

9 Stanton RP, Meehan P, Lovell WW. Surgical fusion in childhood spondylolisthesis. J Pediatric Orthop. 1981;5:411-415.

10 Pizzutilo P, Hummer RA. Nonoperative treatment for painful adolescents with spondylolisthesis J. Pediatric Orthop. 1989;9:538-540.

11 Laurent LE, Osterman K. Operative treatment of spondylolisthesis in young patients. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:85-91.

12 Boxall D, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al. Management of severe spondylolisthesis of children an adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1979;61:479-495.

13 Floman Y. Progression of lumbosacral isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. Spine. 2000;25:342-347.

14 Moller H, Hedlund R. Instrumented and non-instrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis. A prospective randomized study, part 2. Spine. 2000;25:1716-1721.

15 Sue PB, Esses SI, Kostuik JP. Repair of pars interarticularis defect. The prognostic value of pars infiltration. Spine. 1991;16:S445-S448.

16 Ivanic GM, Pink TP, Achatz W, et al. Direct stabilization of lumbar spondylolysis with a hook screw: mean 11-year follow-up period for 113 patients. Spine. 2003;28:255-259.

17 Buck JE. Further thoughts on direct repair of the defect in spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1979;61:123.

18 Bradford DS, Iza J. Repair of the defect in spondylolysis and minimal degree of spondylolisthesis by segmental wire fixation and bone grafting. Spine. 1985;10:673-679.

19 Hefti F, Seelig W, Morscher E. Repair of lumbar spondylolysis by hook screw. Internat Orthpaed. 1992;16:81-85.

20 Deguchi M, Rapoff AJ, Zdeblick TA. Biomechanical comparison of spondylolysis fixation techniques. Spine. 1999;24:328-333.

21 Johnson GV, Thompson AG. The Scott wiring technique for direct repair of lumbar spondylolysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1992;74:426-430.

22 Gill GG. Long-term follow-up of patients with spondylolisthesis treated by excision of the loose lamina with decompression of the nerve roots without spinal fusion. Clin Orthop. 1984;182:215-219.

23 Osterman K, Lindholm TS, Laurent LE. Late results of removal of the loose posterior element (Gill’s operation) in the treatment of lytic lumbar spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:121-128.

24 Lonstein JE. Spondylolisthesis in children: cause, natural history and management. Spine. 1999;24:2640-2647.

25 Peek RD, Wiltse LL, Reynolds JB, et al. In situ arthrodesis without decompression for grade III and IV isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults who have severe sciatica. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:62-68.

26 de Loubresse CG, Bon T, Deburge A, et al. Posterolateral fusion for radicular pain in isthmic spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1996;323:194-201.

27 Bosworth D, Fielding JW, Demarest L, et al. Spondylolisthesis: a critical review of consecutive series of cases treated by arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1955;37:767.

28 Henderson ED. Results of the surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1966;48:61-64.

29 Lenke LG, Bridwell KW, Bullis D, et al. Results of in situ fusion for spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:433-442.

30 Frennered AK, Danielson BI, Nachemson AL, et al. Midterm follow-up of young patients fused in situ for spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1991;16:409-416.

31 Hensinger RN, Lang JR, MacEwin D. Surgical management of spondylolisthesis in childhood and adolescence. Spine. 1976;1:207-215.

32 Hanley EN, Levy JA. Surgical treatment of isthmic spondylolisthesis. Analysis of variables influencing results. Spine. 1989;14:48-50.

33 Schnee CL, Freese A, Ansell W. Outcome analysis for adults with spondylolisthesis treated with posterolateral fusion and transpedicular screw fixation. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:56-63.

34 Haraldsson S, Wilner S. A comparative study of spondylolisthesis in operations on adolescents and adults. Arch Orthop Traum Surg. 1983;101:101-105.

35 Floman Y, Millgram MA, Ashkenazi E, Rand N. Outcome of fusion procedures in isthmic spondylolisthesis presenting in the adult. 23rd annual meeting of the Israeli Orthopedic Association, Tel Aviv; December, 2003.

36 Buttermann GR, Garvey TA, Hunt AF, et al. Lumbar fusion results related to diagnosis. Spine. 1998;23:116-127.

37 Johnson JR, Kirwan EO. The long term results of fusion in situ for severe spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1983;65:43-46.

38 Reynolds JB, Wiltse LL. The treatment of severe spondylolisthesis in the young. Orthop Transactions. 1989;13:27.

39 Seitsalo S, Osterman K, Hyvarinen H, et al. Severe spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. A long-term review of fusion in situ. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1990;72:259-265.

40 Poussa M, Schlenzka D, Seitsalo S, et al. Surgical treatment of severe isthmic spondylolisthesis in adolescents. Reduction or fusion in situ? Spine. 1993;18:894-901.

41 Bradford DS, Godfreid Y. Staged salvage reconstruction of grade IV and V spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1987;69:191-202.

42 Seitsalo S, Osterman K, Hyvarinen H, et al. Progression of spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents: a long term follow up of 272 patients. Spine. 1991;16:417-421.

43 Molinari RW, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Complications in the surgical treatment of pediatric high-grade isthmic dysplastic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1999;24:1701-1711.

44 Schoenecker PL, Cole HO, Herring JA, et al. Cauda equina syndrome after in situ arthrodesis for severe spondylolisthesis at the lumbosacral junction. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:369-377.

45 Edwards CC. Reduction of spondylolisthesis. In: Bridwell KH, DeWald RL, editors. Textbook of spinal surgery. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:1317-1335.

46 Scaglietti O, Frontino G, Bartolozzi P. Technique of anatomical reduction of lumbar spondylolisthesis and its surgical stabilization. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:164-175.

47 Bradford DS. Treatment of severe spondylolisthesis: a combined approach, reduction and stabilization. Spine. 1979;4:423-429.

48 Balderston RA, Bradford DS. Technique for achievement and maintenance of reduction for severe spondylolisthesis using spinous process traction wiring and external fixation of the pelvis. Spine. 1985;10:376-382.

49 Bradford DS. Closed reduction of spondylolisthesis: an experience in 22 patients. Spine. 1988;13:580-587.

50 Bradford DS, Boachie-Adjei O. Treatment of severe spondylolisthesis by anterior and posterior reduction and stabilization. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1060-1066.

51 Burkus JK, Lonstein JE, Winter RB, et al. Long term evaluation of adolescents treated operatively for spondylolisthesis: a comparison of in situ arthrodesis only with in situ arthrodesis and reduction followed by immobilization in a cast. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1992;74:693-704.

52 Zdeblick TA. A prospective randomized study of lumbar fusion. Preliminary results. Spine. 1993;18:983-991.

53 Matthiass HH, Heine J. The surgical reduction of spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1986;203:34-44.

54 Steffee AD, Sitkowski D. Reduction and stabilization of grade IV spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1988;227:82-89.

55 Ani DM, Kepller L, Biscup RS, et al. Reduction of high-grade slips with VSP instrumentation. Report of a series of 41 cases. Spine. 1991;16:S302-S310.

56 Boos N, Marchesi D, Zuber K, et al. Treatment of severe spondylolisthesis by reduction and pedicular fixation. Spine. 1993;18:1655-1661.

57 Petraco DM, Spivak JM, Cappadona JG, et al. An anatomic evaluation of L5 nerve stretch in spondylolisthesis reduction. Spine. 1996;21:1133-1138.

58 Hensinger RN. Point of view. Spine. 1996;21:1139.

59 Kleihaus H, Albrecht S, Noack W. Topographic relations between the neural and ligamentous structures of the lumbosacral junction: In-vitro investigation. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:124-132.

60 Transfeldt EE, Dendrinos GK, Bradford DS. Paresis of proximal lumbar roots after reduction of L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1989;14:884-887.

61 Jackson RP. Jackson’s intrasacral fixation and segmental correction with adjustable contoured translating axes. Spine: State of the Art Review. 1994;8:307-341.

62 DeWald RL, Faut MM, Tadonio RF, et al. Severe lumbosacral spondylolisthesis in adolescents and children. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1981;65:619-626.

63 O’Brien JP, Mehdian H, Jaffray D. Reduction of severe lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;300:64-69.

64 Hu SS, Bradford DS, Transfeldt EE, et al. Reduction of high-grade spondylolisthesis using Edwards instrumentation. Spine. 1996;21:367-371.

65 Harms J, Rolinger H. A one-stager procedure in operative treatment of spondylolistheses: dorsal traction–reposition and anterior fusion. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1982;120:343-347.

66 Fabris DA, Costantini S, Nena U. Surgical treatment of severe L5–S1 spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. Results of intraoperative reduction, posterior interbody fusion and segmental pedicle fixation. Spine. 1996;21:728-733.

67 Huizenga BA. Reduction of spondylolisthesis with staged vertebrectomy. Orthop Transac. 1983;7:21.

68 Gaines RW, Nichols WK. Treatment of spondylolisthesis by two-stage L5 vertebrectomy and reduction of L4 onto S1. Spine. 1985;10:680-686.

69 Lehmer SM, Stefffee AD, Gaines RW. Treatment of L5–S1 spondyloptosis: Staged L5 resection with reduction and fusion of L4 onto S1. Spine. 1994;19:1916-1925.

70 Smith MD, Bohlman HH. Spondylolisthesis treated by a single-stage operation combining decompression with in situ posterolateral fusion and anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:415-420.

71 Esses SI, Natout N, Kip P. Posterior interbody arthrodesis with fibular strut graft in spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:172-176.

72 Roca J, Ubierna MT, Caceres E, et al. One-stage decompression and posterolateral and interbody fusion for severe spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1999;24:709-714.

73 Grob D, Humke T, Dvorak J. Direct pediculo-body fixation in cases of spondylolisthesis with advanced intervertebral disc degeneration. Eur Spine J. 1996;5:281-285.

74 Smith JA, Deviren V, Berven S, et al. Clinical outcome of trans-sacral interbody fusion after partial reduction for high-grade L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2001;20:2227-2234.

75 Bartolozzi P, Sandri A, Ricci M. One-stage posterior decompression-stabilization and trans-sacral interbody fusion after partial reduction for severe L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2003;28:1135-1141.

76 Frymoyer W. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthoped Surgeons. 1994;2:9-15.

77 Farafan HF. The pathological anatomy of degenerative spondylolisthesis: a cadaver study. Spine. 1980;5:412-418.

78 Mardjetko SM, Connolly PJ, Shott S. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. A meta-analysis of literature 1970–1993. Spine. 1994;19:S2256-S2265.

79 Bridwell KH, Sedgewick TA, O’Brien MF, et al. The role of fusion and instrumentation in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:461-472.

80 Robertson PA, Grobler LJ, Novotny JE, et al. Postoperative spondylolisthesis at L4–5. The role of facet joint morphology. Spine. 1993;18:1483-1490.

81 Laus M, Tigani D, Alfonso C, et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: lumbar stenosis and instability. Chir Org Mov. 1992;77:39-49.

82 Herron LD, Trippi AC. The result of treatment by decompressive laminectomy without fusion. Spine. 1989;14:534-538.

83 Fischgrund JS, Mackay M, Herkowitz HN, et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective, randomized study comparing decompressive laminectomy and arthrodesis with and without spinal instrumentation. Spine. 1997;22:2807-2812.

84 Kornblum MB, Fischgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective long-term study comparing fusion and pseudoarthrosis. Spine. 2004;29:726-733.

85 Booth KC, Bridwell KH, Eisenberg BA, et al. Minimum 5-year results of degenerative spondylolisthesis treated with decompression and instrumented posterior fusion. Spine. 1999;24:1721-1727.