Chapter 5 Registration of pharmacists

INTRODUCTION

Historically the regulation of pharmacy in Australia has been achieved through instruments of state-based Acts and regulations. However, recently there has been a move to establish a single national registration scheme for pharmacists — along with other health professions — that had its genesis in a 2006 Productivity Commission report recommending national registration and accreditation mechanisms for the health professions.[1] The report was commissioned by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) which required the Productivity Commission to examine a number of health workforce issues, including supply and demand pressures over the next 10 years.

In the foreword to the report the Productivity Commission Chairman stated:

While this has not been an investigation into health care and its funding, the efficiency and effectiveness of the health workforce is inextricably linked to that broader system, and to Australia’s education and training regime. The Commission considered that it could add most value by reviewing the institutional, regulatory and funding arrangements within its area of focus. It has sought to identify reforms that would produce a more sustainable and responsive health workforce, while maintaining a commitment to high quality and safe health outcomes.[1]

NATIONAL REGISTRATION

[I]n the interests of promoting occupational and commercial mobility, the Commonwealth, States and Territories explore and consider adopting nationally consistent or uniform legislation, or specific legislative provisions on pharmacy ownership, pharmacist registration and the regulation of pharmacy professional practice.[2]

At the July 2006 COAG meeting it was agreed a single national registration scheme for health professionals, beginning with the nine professional groups currently registered in all jurisdictions, would be established.[2] Pharmacy is included as one of the nine. This decision arose from a 2005 Productivity Commission Research Report titled Australia’s Health Workforce that recommended both a single national registration board for health professionals and a single national accreditation board for health professional education and training. The recommendation aimed to deal with workforce shortages and pressures faced by the Australian health workforce, to increase flexibility, responsiveness, sustainability and mobility of health professionals, and reduce red tape.[1] At a meeting in 2008 COAG agreed to establish the scheme by 1 July 2010. It subsequently agreed:

[T]o establish a single national scheme, with a single national agency encompassing both the registration and accreditation functions. The national registration and accreditation scheme will consist of a Ministerial Council, an independent Australian Health Workforce Advisory Council, a national agency with an agency management committee, national profession-specific boards, committees of the boards, a national office to support the operations of the scheme, and at least one local presence in each State and Territory.[3]

The objectives of the scheme, to be set out in legislation, are to:

To implement the scheme Queensland will host the substantive legislation giving effect to the national scheme. The other states and territories will subsequently enact their own legislation, which will effectively adopt the Queensland provisions.[4] Each of the states and territories will ‘use their best endeavours’ to repeal their existing registration legislation covering the health professionals subject to the new scheme. The legislation will be introduced in the Queensland Parliament in two stages. The first stage will address the structural elements of the scheme and the second stage will cover other matters including arrangements for:

The consultation paper proposes that the registration provisions build on the best aspects of state and territory schemes, endeavouring to avoid a ‘lowest common denominator’ approach or merely replicating one registration scheme.[4] One of the stated aims is to develop the least restrictive law necessary to achieve the policy directive of enabling a robust system designed to protect the public. Restrictions on practice will only be imposed where the benefits to the community outweigh the costs.

The consultation paper further proposes that the legislation provide powers to the national boards for the purpose of ensuring that registered practitioners meet minimum accepted standards of competence and are safe to practise.[4] This reflects the increased community expectations that boards take a more active role with respect to ensuring health practitioners are safe and competent to practise. It is expected that the legislation will require the boards to establish recency of practice requirements within each profession to ensure registrants demonstrate continuing competence at the time of annual renewal.

The consultation paper also flags a requirement for registrants to be covered by professional indemnity insurance. The Queensland Pharmacists Registration Act 2001 is the only state pharmacy registration Act that does not include this requirement. Currently the major provider of professional indemnity insurance for pharmacists in Australia is Pharmaceutical Defence Limited (PDL). This defence organisation was formed in 1912 after legal action against a chemist, Francis Gough, in Echuca, who was sued for damages by a farmer, William Hilton, following an alleged poisoning in 1911. Hilton won the case and was awarded damages of £200 plus costs. Chemists realised their vulnerability in regard to such errors, whether the errors arose from their own practice, or the errors or omissions of others.[5] Money was subsequently raised from the profession and was sufficient, not only to assist Gough, but also to form PDL. PDL provides legal advice and representation to pharmacists where complaints and allegations involving professional practice have the potential to result in a civil action. PDL will also provide legal representation if a pharmacist is called before an inquest.

The Australian Pharmacy Council Inc (APC) (formerly the Council of Pharmacy Registering Authorities [COPRA]) will also be a significant organisation in the development of a national system of registration. The APC was formed in 2002 as the national body for Australian state and territory authorities responsible for the registration of pharmacists. The principal purposes of the APC are to:

STATE- AND TERRITORY-BASED REGISTRATION

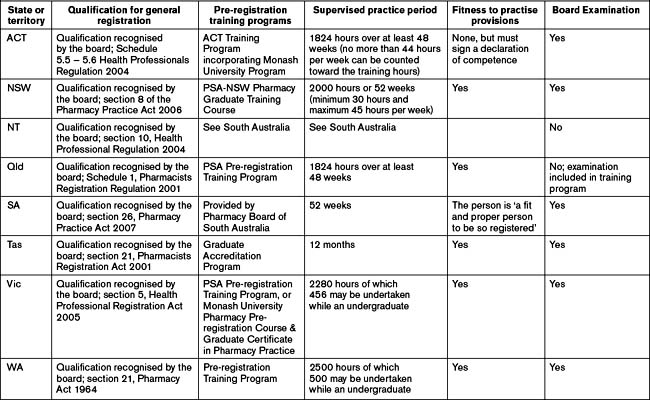

Periods of supervised practice to be undertaken to fulfil the requirement for registration vary slightly from state to state, but equate to a period of approximately one year. Some Acts or regulations express the period as a number of hours to be worked over not less than a defined period (the Queensland Act for example expresses the period as ‘… 1824 hours to be worked over at least 48 weeks …’).

The requirements of the individual jurisdictions regarding initial registration are summarised in Table 5.1.

The following section provides a general overview of the registration requirements for each Australian state and territory.

Australian Capital Territory

To show continuing competence the applicant may be required to give the board:

New South Wales

Under the Health Care Liability Act 2001 a person is not entitled to practise as a pharmacist unless the person is covered by professional indemnity insurance, and the Pharmacy Board (the board) cannot register a person as a pharmacist unless satisfied that the person is covered by professional indemnity insurance. Further, the board may cancel or suspend the registration of a person as a pharmacist, if the board is satisfied that the person is not covered by professional indemnity insurance while practising as a pharmacist. This requirement does not apply to, or in respect of, a pharmacist who is exempt under the regulations from the requirement of being covered by approved professional indemnity insurance.

Northern Territory

Part 6 of the Act authorises the board to undertake an assessment of a pharmacist’s professional performance. For the purposes of the Act a pharmacist’s professional performance ‘… is unsatisfactory if it is below the standard reasonably expected of health practitioners of an equivalent level of training or experience …’. The appointment of assessors is subject to section 89 of the Act and an assessor must be a person who is considered to have skill, knowledge or experience relevant to the assessment.

Queensland

A person’s general registration may be cancelled pursuant to section 86 of the Act if it is found that the person was registered because of a materially false or misleading representation or declaration.

South Australia

In addition to registration, pharmacists seeking to practise in South Australia require a practising certificate, which the board will issue on application. Practising certificates may be subject to conditions, limiting the kind of pharmacy services the holder of the certificate my provide until the holder completes or obtains further education, training or experience as determined by ‘practice rules’. Practice rules establish a scheme for further education, training and experience for pharmacists and govern the requirements for practising certificates and the imposition of, and evidence of compliance with, conditions of practising certificates. A registered pharmacist must satisfy the Pharmacy Board of their competence as a provider of restricted pharmacy services. In order to gain a practising certificate a registered pharmacist must participate in, and successfully complete, the process of the board’s ENRICH program.

Tasmania

Under section 25 the board may hold an enquiry into any applicant for registration. Such an inquiry must be undertaken by a committee appointed by the board. The applicant must receive a notice outlining the reasons for holding the inquiry and the date, time and place the inquiry is to be conducted. At the conclusion of the inquiry the committee must provide a written report with recommendation to the board outlining the evidence on which the findings were made.

Victoria

Under section 6(2), the board may refuse to grant registration on a number of grounds including:

Western Australia

The regulation of pharmacists in Western Australia is carried out under the Pharmacy Act 1964 (WA). It was anticipated that this Act would be repealed and replaced by the Western Australian Pharmacists Act 2006 that is currently a Bill before the parliament, and which had its first reading and second reading in the Legislative Assembly on 29 November 2006 and its third reading on 5 April 2007. However, with the current development of a national registration scheme for health practitioners, some doubts have been expressed about whether the Bill will in fact be enacted, or whether it will be bypassed and legislation harmonious with national registration introduced in its place.

In registering an applicant the board may impose such conditions as it sees fit, including that ‘… a pharmacist must hold professional indemnity insurance; or the practice of pharmacy by a pharmacist must be covered by professional indemnity insurance …’ (s27).

Registration is renewed annually through the payment of a fee prescribed in a regulation.

MUTUAL RECOGNITION

For the purposes of legislation:

… ‘occupation’ means an occupation, trade, profession or calling of any kind that may be carried on only by registered persons, where registration is wholly or partly dependent on the attainment or possession of some qualification (for example, training, education, examination, experience, character or being fit or proper), and includes a specialisation in any of the above in which registration may be granted …[6]

A person who is registered in the first state or territory for an occupation may lodge a written notice with the local registration authority of the second state or territory for the equivalent occupation, seeking registration for the equivalent occupation in accordance with the mutual recognition principle.

It should be noted that where a state or territory requires both registration and a license or practising certificate to practise, a second jurisdiction, which may only require registration to practise may not register a person from the first jurisdiction who was merely registered but held neither a license nor practising certificate. For example, a pharmacist from New Zealand who was registered with the Pharmacy Board of New Zealand did not hold a current practising certificate in that country, therefore could not register under mutual recognition with an Australian jurisdiction which did not require a practising certificate to practise pharmacy. The recognition would not be mutual as the Australian registration may entitle the person to practise where the registration in New Zealand would not.

ADMINISTRATION OF REGISTRATION ACTS

Australian Capital Territory

Part 7, Health professions tribunal, Part 9, Reporting, Part 10, Joint consideration with commission, Part 11, Personal assessment panels, and Part 12, Professional standards panels, all cover matters relating to complaint, investigation and disciplinary hearings and are discussed in Chapter 7 (Investigation, discipline and legal proceedings).

Part 8, Offences, deals with offences created under the Act including the provision of regulated health services by unregistered persons and the false representation of a person as a health professional. It also requires that a registrant comply with any condition imposed on this registrant and makes it an offence to direct a person to engage in unprofessional conduct, practise without indemnity insurance if such is required by regulation, or to supply drugs or medicines that do not comply with standards applicable under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) or a standard stated in the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary Handbook.

New South Wales

Part 11, Prohibition against directing or inciting misconduct, prohibits a person who employs a registered pharmacist from directing or inciting the pharmacist to engage in conduct in the course of professional practice that would constitute unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct. The Part contains extended definitions of the terms ‘employment’ and ‘carrying on business’, where a conviction may prohibit an offender from carrying on a pharmacy business.

Northern Territory

The objectives of this Act are:

Part 4, Professional conduct, includes matters of complaint and discipline and are discussed in Chapter 7 (Investigation, discipline and legal proceedings).

Part 5, Impaired health practitioners, provides the board with powers to address matters relating to impairment. A person may notify the relevant board if he or she considers a health practitioner’s ability to practise is or may be affected by the health practitioner’s addiction to alcohol or another drug, lack of mental or physical competence, or state of health. In these circumstances the board may appoint a person or persons to investigate the allegations. If it is satisfied that a health practitioner’s ability to practise is or may be affected it may do either or both of the following: accept an undertaking from the health practitioner to take or refrain from taking specified action; impose any condition it thinks fit on the health practitioner’s right of practice or authorisation to practice; or decide to take no action under this Part but refer the matters to be investigated under Part 4 or 6.

Part 6, Performance assessment, empowers the board to assess:

Queensland

The objects of the Act are to protect the public by ensuring health care is delivered by registrants in a professional, safe and competent way, to uphold the standards of practice within the profession, and to maintain public confidence in the profession. These objects are to be achieved through establishing the Pharmacists Board of Queensland, providing for the registration of persons under this Act, imposing obligations on persons in relation to the practice of the profession, and providing for compliance with the Act to be monitored and enforced.

The Regulation also sets out the fees payable under the Act.

South Australia

The Pharmacy Practice Act 2007 is:

Part 2, Pharmacy Board of South Australia, addresses the establishment, composition, registrar and staff of the board, general functions and powers, board’s procedures, and the accounts, audit and annual report, constitution, functions and administrative provisions of the board. The functions of the board are defined in section 13 and are as follows:

Part 6, Miscellaneous, addresses a range of other matters including:

Tasmania

Victoria

Part 4, Investigations and panel hearings, Part 5, Proceedings and review by VCAT, and Part 6, Offences and regulated conduct, will be addressed in Chapter 7.

Western Australia

Part 3, Registration of pharmaceutical chemists and pharmacies, includes the qualifications for registration, the processes of registration for pharmacists and the restrictions on the carrying on of a pharmacy. Also included are fees for registration and the requirement to publish a list of pharmacists in February of each year.

Part 5, Miscellaneous provisions, includes matters related to:

Part 8, Proceeding, is the form of certificate given pursuant to section 40A(6)(a) of the Act.

Part 9, Miscellaneous, states: that books or records must be kept for 2 years; that a council officer may inspect premises, books or other records; that making false or misleading statements in relation to any application for registration as a pharmacist or of premises is an offence against the Act; and that persons who contravene or neglect, refuse, or fail to comply with any provisions of these Regulations shall be guilty of an offence.

Productivity Commission. Australia’s Health Workforce. Canberra: Research Report; 2005.

Wilkinson W. National Competition Review of Pharmacy. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments; 2000.

Council of Australian Governments. Intergovernmental Agreement for a National Registration and Accreditation Scheme. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments; 2006.

Haines G. Pharmacy in Australia: The National Experience. Canberra: Australian Pharmaceutical Publishing Co Ltd for the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia; 1988.

1 Productivity Commission. Australia’s Health Workforce. Canberra: Research Report; 2005.

2 Wilkinson W. National competition review of pharmacy. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments; 2000.

3 Council of Australian Governments. Intergovernmental agreement for a national registration and accreditation scheme for health professions. Council of Australian Governments. Canberra. Online. Available: www.nhwt.gov.au/documents/National%20Registration%20and%20Accreditation/NATREG%20-%20Intergovernmental%20Agreement.pdf [accessed 30 October 2008]

4 Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council. National registration and accreditation scheme for health professions. Consultation paper, Canberra. 19 September 2008. Online. Available: www.nhwt.gov.au/documents/National%20Registration%20and%20Accreditation/Call%20for%20submissions%20on%20proposed%20registration%20arrangements.pdf [accessed 30 October 2008]

5 Haines G. The grains and three penn’orths of pharmacy: pharmacy in New South Wales 1788–1976. Lowden Publishing; 1976. 206