Chapter 46 Rating of Athletic and Daily Functional Activities after Knee Injuries and Operative Procedures

INTRODUCTION

Outcome measures are available for older or sedentary populations with osteoarthritis such as the Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities (WOMAC),1 the Knee Pain Scale,18 and the Knee Society Clinical Rating System.8 There are also several generic health status instruments, such as the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 (SF-12). It is not the purpose of this chapter to review these instruments. Scales from the Cincinnati Knee Rating System (CKRS) and the International Documentations Committee Rating System are not included, because they are described in detail in Chapters 44 and 45, respectively.

SPORTS ACTIVITY SCALES

Tegner Activity Scale

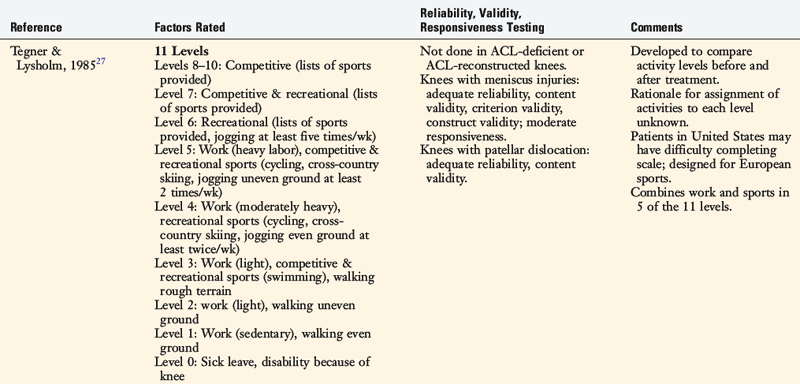

Tegner and Lysholm27 developed one of the first rating scales to quantify activity levels in patients with ACL ruptures (Table 46-1). The Tegner Activity Scale classifies both sports and work activities into one questionnaire using an 11-level gradient. Competitive sports make up the top three levels (levels 10–8), competitive and recreational sports categories both appear in level 7, and “other recreational sports” make up level 6 (Table 46-2). Levels 5 through 1 combine work and sports together, and level 0 indicates sick leave or disability due to the knee condition. The original publication did not provide reliability, validity, or responsiveness data of this scale.

| Level Number | Level Descriptor | Examples of Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Competitive sports | Soccer—national and international elite |

| 9 | Competitive sports |

From Tegner, Y.; Lysholm, J.: Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 198:43–49, 1985.

Critical Points SPORTS ACTIVITY SCALES

Tegner Activity Scale

Seto Sports Participation Survey

Straub and Hunter’s Sports Performance Index

Several problems are incurred with this activity rating instrument. First, work activities are rated within the same scale as sports activities. Patients who work in heavy-labor occupations are awarded only a level 5 (out of a possible 10), but the analysis of the stress on the lower limb in some of these occupations would probably show that these knees are functioning at a level equivalent to that of competitive athletes. They should not be awarded a lower level simply because they are not athletes or did not return to highly competitive sports. Athletics and occupational activities should be measured on separate rating scales (see Chapter 44).

Two independent investigations assessed the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Tegner scale. Briggs and coworkers3 determined its reliability, validity, and responsiveness in 122 patients with meniscus injuries. The scale was found to have adequate reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC], 0.817), content validity (no ceiling or floor effects), criterion validity with the generic SF-12 scale, and construct validity. However, only moderate effect sizes and standardized response mean values were reported. The investigators concluded that the scale measures only moderate changes in activity levels and noted that patients in the United States may have difficultly completing the scale because it was designed for sports commonly played in Europe. Paxton and associates17 assessed the reliability and validity of this scale in 153 patients followed 2 to 5 years after an acute patellar dislocation. The scale was found to have adequate reliability (ICC, 0.92) and content validity.

Modified Hospital for Special Surgery Sports Scale

The modified Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) knee assessment instrument (see Table 46-2) was developed for an investigation of 48 patients with ACL-deficient knees who underwent arthroscopic partial meniscectomy.6 The instrument includes a scale composed of four levels of various sports ranked “very stressful,” “moderately stressful,” “mildly stressful,” and “no sports activities.” Examples of sports are provided in categories A, B, and C to assist with the ratings. The advantages of this scale include the assessment of sports activities only (separately from occupations) and the attempt to sort sports participation according to the level of intensity. The problems with this scale are that ambiguous terms are used to rate the sports categories (as “very stressful” may have different meanings to different patients), an assessment of reasons for change in athletics owing to non–knee-related reasons is not provided, and the detection of knee abusers is not possible. The authors did not conduct reliability, validity, or responsiveness testing of their outcome instrument.

Seto Sports Participation Survey

Seto and colleagues24 developed a sports participation survey in order to determine activity levels in 19 patients who had undergone ACL reconstruction. In this survey, subjects rated their activity level for 13 sports, which are divided into cutting and noncutting categories. Each sports activity receives 0 to 4 points, based on the ability to participate with no symptoms (4 points), participate with “recurring mild episodes of pain, swelling, or instability” (3 points), limited participation owing to “moderate or severe episodes of pain, swelling, or instability” (2 points), or not able to participate owing to either knee-related (1 point) or non–knee-related (0 points) reasons.

Straub and Hunter’s Sports Performance Index

Straub and Hunter26 devised a sports performance index to determine the outcome of ACL reconstruction. The index is based on scores from two factors: a participation level rating and an intensity level rating. The participation level rating is accomplished on a six-level gradient that ranges from professional (5 points); intercollegiate (4 points); intramural (college), varsity (high school) or recreational (intense) (3 points); casual (2 points); junior high school (1 point); to no sports (0 points). The intensity rating scale sorts various sports into categories according to the authors’ perception of the intensity of those activities on the lower extremity. The most intense activities receive 5 points and the least intense receive 1 point. The two rating scores are summed to produce a sports performance index.

Daniel Sports Activity Rating

Daniel and coworkers4 described a sports rating scheme that was used to determine outcome in both ACL-deficient and ACL-reconstructed knees. The sports activity rating assessed frequency of participation (number of hours played per year) and intensity of the activities. Frequency of participation is determined in a retrospective manner; patients are asked to recall the two most frequent sports they played in before their ACL rupture and to provide the number of weeks per year and the number of hours per week that they played each sport. The number of hours per year of participation in the two sports is summed. A four-level intensity rating is also included in which level I comprises jumping, pivoting, and hard cutting activities; level II, lateral motion but less jumping or hard cutting than level I; level III, “other sports”; and level IV, no sports. A few examples of sports are provided for levels I, II, and III.

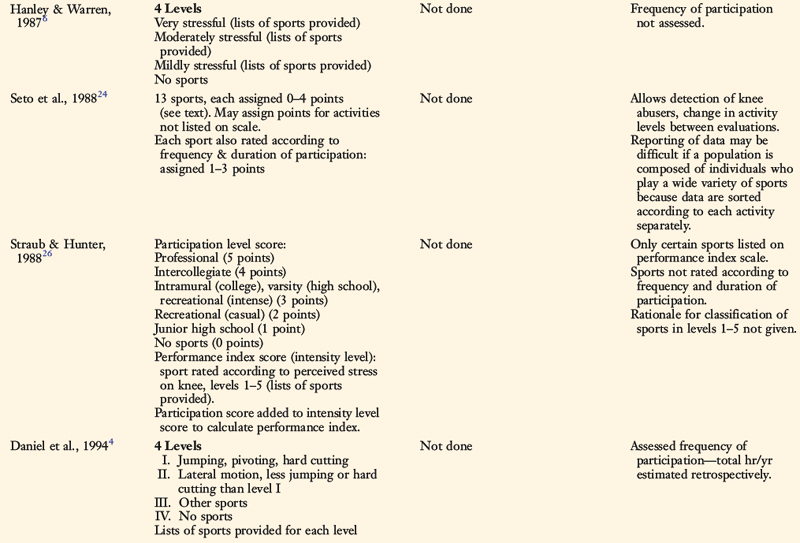

Marx Sports Activity Scale

Marx and associates14 developed a sports activity rating scale to use as a general research tool to determine outcome for a variety of knee injuries and operations. This scale takes into account frequency of participation and intensity of the activity. Four separate activities are rated: running, cutting, decelerating, and pivoting. Frequency of participation for each activity is classified as either “none,” “1 time a month,” “1 time a week,” “2 or 3 times a week,” and “4 or more times a week.”

ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING SCALES

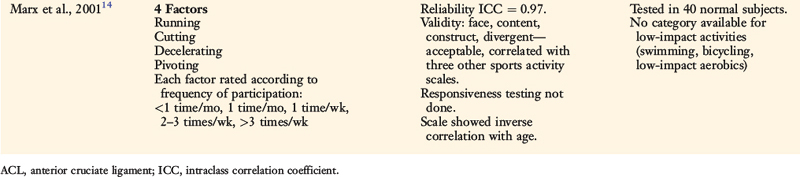

Lysholm Knee Score

The Lysholm knee score, first introduced into the medical community in 198212 and modified in 1985,27 remains one of the most frequently used assessment tools for the results of ACL reconstruction even though it measures only activities of daily living (ADL; Table 46-3). Eight factors are rated to produce an overall score on a point scale of 0 to 100. Then, an assignment is given as “excellent” for 95 to 100 points; “good” for 84 to 94 points, “fair” for 65 to 83 points, or “poor” for less than 65 points. The factors of limp, support, and locking are worth a potential of 23 points; pain and instability, 25 points each; swelling and stair-climbing, 10 points each; and squatting, 5 points.

| Factor | Scale | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Limp |

Critical Points ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING SCALES

Lysholm Knee Score

ADL Scale of the Knee Outcome Survey

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

The symptoms of pain, swelling, and instability are graded according to the activity in which they occur. For example, for the factor of instability, patients may receive 15 of a possible 25 points if they experience instability frequently during athletics or heavy exertion (or are unable to do these activities). Independent studies have demonstrated that the Lysholm system “may inflate results, particularly if raw scores are combined to obtain an overall final rating”25 and is “less sensitive for ACL patients … than three other diagnostic categories.”2 Risberg and colleagues19 found poor sensitivity in detecting changes over time (responsiveness) and concluded, “The Lysholm score was not sensitive to detect changes over time, and therefore it is not recommended as an outcome measurement after ACL reconstruction.”19

Other authors have reported adequate reliability and responsiveness of this scale when it was tested in combined samples of patients with a variety of knee disorders including ligament and meniscus injuries, patellofemoral pain, and degenerative joint disease. Irrgang and coworkers9 assessed internal consistency, criterion validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm scale in a group of 397 patients who had a wide variety of knee disorders. Data collected at baseline and at 1, 4, and 8 weeks later were compared with those obtained with the authors’ Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale. The Lysholm scale demonstrated adequate criterion validity with the ADL scale (Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients ranged from R = 0.78 at baseline to R = 0.86 at 8 wk postbaseline) and with the patients’ global rating of the overall knee condition. Large effect sizes (>0.80), indicating adequate responsiveness, were noted at 4 and 8 weeks postbaseline testing. Internal consistency of the Lysholm scale was lower than that of the ADL scale, resulting in higher standard error of measurement for all time periods of data collection.

Marx and associates13 determined reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm scale along with the subjective components of the CKRS, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) sports knee-rating scale, and the ADL scale in a population of patients with a wide variety of knee disorders. All of the scales demonstrated high reliability (ICCs > 0.80), adequate face and content validity, and responsiveness (standardized response means > 0.80).

Paxton and associates17 measured the reliability and validity of the overall Lysholm score in 153 patients followed 2 to 5 years after an acute patellar dislocation. The overall score demonstrated adequate reliability (ICC, 0.88), content validity, and construct validity. Kocher and colleagues11 assessed the Lysholm scale in a population of 1657 patients with traumatic and degenerative chondral lesions. Adequate reliability was found for the overall score and all individual components of the scale except for pain and stair-climbing. Adequate content validity was found for the overall score. However, unacceptably high ceiling effects were found for the domains of limp, instability, support, and locking and a high floor effect was found for the domain of squatting. Criterion validity was acceptable, with significant correlations between the overall score and the SF-12, Western Ontario, and Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities (WOMAC) scales. Construct validity was proved in the nine hypotheses generated by the investigators. Adequate responsiveness was found for the overall score and all of the individual components except for instability.

Briggs and coworkers3 determined reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm scale in patients with meniscus injuries. Adequate reliability was reported for the overall score and all individual components except locking. Acceptable content validity was found for the overall score. However, high ceiling effects were reported for the domains of limp, instability, support, and locking and a high floor effect was found for the domain of squatting. Criterion validity was adequate, because the scale correlated with the physical component score of the SF-12. Acceptable construct validity was proved, with all eight hypotheses developed by the authors found to be significant. The overall score had adequate responsiveness, with large effect sizes and standardized response means. However, the individual domains of instability, locking, limping, support, and swelling had only small to moderate effect sizes.

ADL Scale of the Knee Outcome Survey

Irrgang and coworkers9 developed the ADL Scale (Table 46-4) to measure limitations in patients with a variety of knee disorders including ligament ruptures, patellofemoral pain, meniscus tears, and articular cartilage damage. The scale rates seven symptoms and 10 functions. The symptoms (pain, crepitus, stiffness, swelling, instability, and weakness) are rated on a six-level gradient as either (1) never occurs with ADL (5 points), (2) occurs but does not affect ADL (4 points), (3) occurs and slightly affects ADL (3 points), (4) occurs and moderately affects ADL (2 points), (5) occurs and severely affects ADL (1 point), or (6) prevents all ADL (0 points).

Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

Roos and coworkers22 developed the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) scale to assess symptoms and functional limitations with activity for patients with ACL or meniscus injuries or post-traumatic osteoarthritis. The scale is composed of five “dimensions” that are scored separately, including pain (9 questions), symptoms (7 questions), ADL (17 questions), sport and recreational function (5 items, includes squatting and kneeling), and knee-related quality of life (4 questions). The ADL questions are composed of the original 17 WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index Physical Function questions. Therefore, the score of the KOOS ADL dimension is equal to that of the WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index.

No patient in the authors’ original series had osteoarthritis or an isolated meniscus tear. However, later studies by Roos and associates23 provided evidence of satisfactory reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the KOOS for patients who had total knee replacement, meniscectomy, or post-traumatic osteoarthritis.20,21 The questionnaire format does not provide an analysis of the activity level in which symptoms occur, other than daily activities. Although the scales assess certain sports functions, an activity rating for athletics is not provided, and therefore, it is unknown what activities patients are actually participating in or whether a change in activity level occurred between evaluations. Ambiguous terminology to define gradient levels can be problematic, because patients may interpret terms such as “moderate,” “severe,” and “extreme” differently. Some may assign a grade according to the frequency of the problem, others according to the intensity of the problem, and still others may use a combination of frequency and intensity to assign a rating.

AAOS Lower Limb Scale

The AAOS developed a Lower Limb Core Scale in order to determine pain, stiffness, swelling, and ADL function for a wide variety of knee disorders.10 The scale is composed of seven questions and designed to be treated as a summative scale to be used either alone for lower limb diagnoses or as a joint-specific scale for hip and knee or foot and ankle problems. The scale was administered to 70 patients with ligament or meniscus injury, patellofemoral pain, and degenerative joint disease. Johanson and associates10 reported good construct validity, with adequate correlation coefficients of this scale to other instruments such as the SF-36 and the WOMAC. However, there were limitations to this study. Reliability was not assessed with ICC, rather with correlation coefficients that the authors expressed was a potential limitation. Responsiveness was not determined in a large sample size, and floor and ceiling effects were not calculated.

GLOBAL ASSESSMENT SCHEMES

Mohtadi15 devised a quality of life outcome instrument for ACL-deficient knees. The questionnaire is composed of 31 questions in a visual analog scale (VAS) format and sorted into five domains. There are 5 items in the area of symptoms and physical complaints, 4 items in the area of work, 12 items in the area of sports, 6 items in the area of lifestyle, and 5 items in the area of social and emotion.

Critical Points GLOBAL ASSESSMENT SCHEMES

Mohtadi Quality of Life Outcome Instrument for Anterior Cruciate Ligament–Deficient Knees

Visual Analog Scales

A subjective knee score comprising 28 questions in a VAS format was originally described by Flandry and colleagues5 and later by Hoher and coworkers.7 The questionnaire combines symptoms and athletic and daily activity functions into one overall score. The instrument is weighted to an assessment of ADL, because 12 questions (43%) refer to ADL and only 5 (18%) assess sports activities. The questionnaire’s reliability was assessed in 25 volunteers with normal knees and in 21 patients with a variety of knee disorders. The correlation coefficients of the score were 0.86 in the volunteers and 0.92 in the patients. Whereas the score was able to detect a significant difference between normal and injured subjects, only a highly competitive athlete could score the maximum of 100 points. Construct validity, tested against the Lysholm score and an older version of the CKRS,16 showed adequate correlation coefficients. Other validity analyses were not conducted. Responsiveness effect size data were not provided.

There are many problems with these global VAS questionnaires. VAS formats do not allow for an analysis of symptoms or functional limitations according to activity level. Therefore, results of studies from different clinicians cannot be accurately compared with the knowledge of the percentage of patients who have symptoms with strenuous, moderate, light sports activities or with ADL. Because these instruments combine a variety of factors including symptoms, work, athletics, social, and emotional issues into one final score, there is no effective manner to address these items separately. Mohtadi’s final score16 is weighted for sports, which is problematic for patients who do not return to sports for reasons not related to the knee condition. Conversely, Hoher and coworkers’s final score7 is weighted for ADL and thereby loses sensitivity in defining functional limitations in athletic populations.

1 Bellamy N., Buchanan W.W., Goldsmith C.H., et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833-1840.

2 Bengtsson J., Mollborg J., Werner S. A study for testing the sensitivity and reliability of the Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1996;4:27-31.

3 Briggs K.K., Kocher M.S., Rodkey W.G., Steadman J.R. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm Knee Score and Tegner Activity Scale for patients with meniscal injury of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:698-705.

4 Daniel D.M., Stone M.L., Dobson B.E., et al. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632-644.

5 Flandry F., Hunt J.P., Terry G.C., Hughston J.C. Analysis of subjective knee complaints using visual analog scales. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:112-118.

6 Hanley S.T., Warren R.F. Arthroscopic meniscectomy in the anterior cruciate ligament–deficient knee. Arthroscopy. 1987;3:59-65.

7 Hoher J., Munster A., Klein J., et al. Validation and application of a subjective knee questionnaire. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3:26-33.

8 Insall J.N., Dorr L.D., Scott R.D., Scott W.N. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:13-14.

9 Irrgang J.J., Snyder-Mackler L., Wainner R.S., et al. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1132-1145.

10 Johanson N.A., Liang M.H., Daltroy L., et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons lower limb outcomes assessment instruments. Reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:902-909.

11 Kocher M.S., Steadman J.R., Briggs K.K., et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm Knee Scale for various chondral disorders of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1139-1145.

12 Lynch M.A., Henning C.E., Glick K.R.Jr. Knee joint surface changes. Long-term follow-up meniscus tear treatment in stable anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;172:148-153.

13 Marx R.G., Jones E.C., Allen A.A., et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of four knee outcome scales for athletic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1459-1469.

14 Marx R.G., Stump T.J., Jones E.C., et al. Development and evaluation of an activity rating scale for disorders of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:213-218.

15 Mohtadi N. Development and validation of the quality of life outcome measure (questionnaire) for chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:350-359.

16 Noyes F.R., McGinniss G.H. Controversy about treatment of the knee with anterior cruciate laxity. Clin Orthop. 1985;198:61-76.

17 Paxton E.W., Fithian D.C., Stone M.L., Silva P. The reliability and validity of knee-specific and general health instruments in assessing acute patellar dislocation outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:487-492.

18 Rejeski W.J., Ettinger W.H.Jr., Shumaker S., et al. The evaluation of pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: the knee pain scale. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1124-1129.

19 Risberg M.A., Holm I., Steen H., Beynnon B.D. Sensitivity to changes over time for the IKDC form, the Lysholm score, and the Cincinnati knee score. A prospective study of 120 ACL reconstructed patients with a 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:152-159.

20 Roos E.M., Klassbo M., Lohmander L.S. WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients with arthroscopically assessed osteoarthritis. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28:210-215.

21 Roos E.M., Roos H.P., Lohmander L.S. WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index—additional dimensions for use in subjects with post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Western Ontario and MacMaster Universities. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:216-221.

22 Roos E.M., Roos H.P., Lohmander L.S., et al. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:88-96.

23 Roos E.M., Toksvig-Larsen S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:17.

24 Seto J.L., Orofino A.S., Morrissey M.C., et al. Assessment of quadriceps/hamstring strength, knee ligament stability, functional and sports activity levels five years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:170-180.

25 Sgaglione N.A., Del Pizzo W., Fox J.M., Friedman M.J. Critical analysis of knee ligament rating systems. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:660-667.

26 Straub T., Hunter R.E. Acute anterior cruciate ligament repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;227:238-250.

27 Tegner Y., Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:43-49.