192 Rash in the Severely Ill Patient

• Identification of rash morphology is paramount for elucidating the differential diagnoses of potentially lethal rashes.

• History taking must include occupation, travel, medications, comorbid conditions, and immune status.

• Complete and serial physical examinations are needed for proper evaluation of any patient with a potentially lethal rash.

• Blood cultures and early antibiotic administration are crucial because most potentially lethal rashes have an infectious cause.

• The clinical manifestations of Rocky Mountain spotted fever and meningococcemia are very similar. With any diagnostic uncertainty, treat for both.

• Petechial and purpuric rashes are marked by high morbidity and mortality.

• Petechiae and fever are very concerning. These patients may decompensate rapidly and require aggressive care.

• Palpable petechiae are due to vasculitides and may have an infectious cause.

• Nonpalpable petechiae are most often associated with thrombocytopenia.

• Hemorrhagic bullae are ominous.

• Patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis and other skin-sloughing diseases desquamate extensively and may require admission to a burn unit.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

History Taking

The history is of paramount importance in the diagnosis of a patient with a rash. Of particular concern is an accounting of any recent travel, the patient’s own geographic location, medical and occupational history, animal exposure, and medication regimens. Table 192.1 classifies rashes in severely ill patients by exposure to geographic regions and animals.

Table 192.1 Rashes in Severely Ill Patients by Geographic and Animal Exposure

| DISEASE | DISEASE HIGHLIGHTS | |

|---|---|---|

| By Geographic Exposure | ||

Northeastern  of United States of United States |

Lyme disease | |

Exposure to infected or dead animals or their products

Physical Examination

At the start it is very important to evaluate the vital signs of toxic-appearing patients with rashes. Fever and hypotension are of particular concern and mandate expedited and intensive care. A complete examination should include evaluation for any new-onset heart murmur, changes in mental status, and nuchal rigidity. Of particular importance are the onset and progression of the rash; involvement of the palms, soles, and mucous membranes; and the age of the patient. An algorithmic approach can aid greatly in the identification of systemically ill patients with a rash. Table 192.2 categorizes rash characteristics in severely ill patients.

| Centripetal progression | RMSF, EM major |

| Centrifugal progression | Viral exanthems, smallpox |

| Rash with palm and sole involvement | EM, RMSF, bacteremic endocarditis, syphilis, erythroderma |

| Rash with mucous membrane involvement | EM major, TEN, SJS, pemphigus vulgaris, syphilis |

| Rash with rapid spread | Urticaria, anaphylaxis, meningococcemia, erythroderma |

| Rash with hypotension | Meningococcemia, TSS, RMSF, TEN, SJS |

| 0-5 yr | Meningococcemia, Kawasaki disease, viral exanthems |

| >65 yr | Bullous pemphigus, sepsis, meningococcemia, TEN, SJS, TSS |

EM, Erythema multiforme; RMFS, Rocky Mountain spotted fever; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; TSS, toxic shock syndrome

Physical Signs

Two signs are important in the evaluation of these rashes, the Nikolsky sign and the Asboe-Hansen sign. A positive Nikolsky sign (Fig. 191.1) is noted when slight rubbing of the skin results in exfoliation of the outermost layer with lateral extension of the erosion into intact skin. The area of denuded skin is pink and tender. The Asboe-Hansen sign (indirect Nikolsky sign or Nikolsky II sign) is extension of a blister into normal skin with the application of light pressure on top of the blister. All patients with tender, blistering, or sloughing skin should be evaluated serially for these important signs.

Differential Diagnois and Medical Decision Making

Algorithmic Approach to Classification

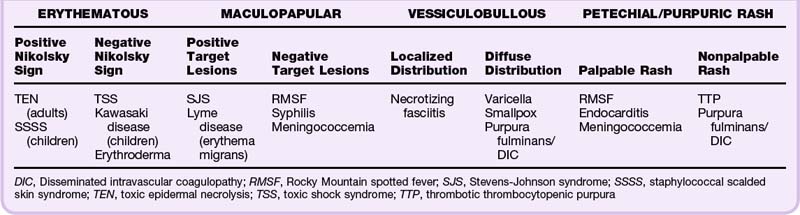

It is helpful to first define the rash into one of four types: erythematous, maculopapular, vesiculobullous, or petechial/purpuric (see Chapter 191 for more detailed review). Erythematous rashes can then be further classified into those with or without a positive Nikolsky sign. Maculopapular rashes may be subdivided into those with or without target lesions. Vesiculobullous rashes should be differentiated into those with a localized or a diffuse distribution. Petechial/purpuric rashes should be classified into those with palpable or nonpalpable rash morphology (Table 192.3).

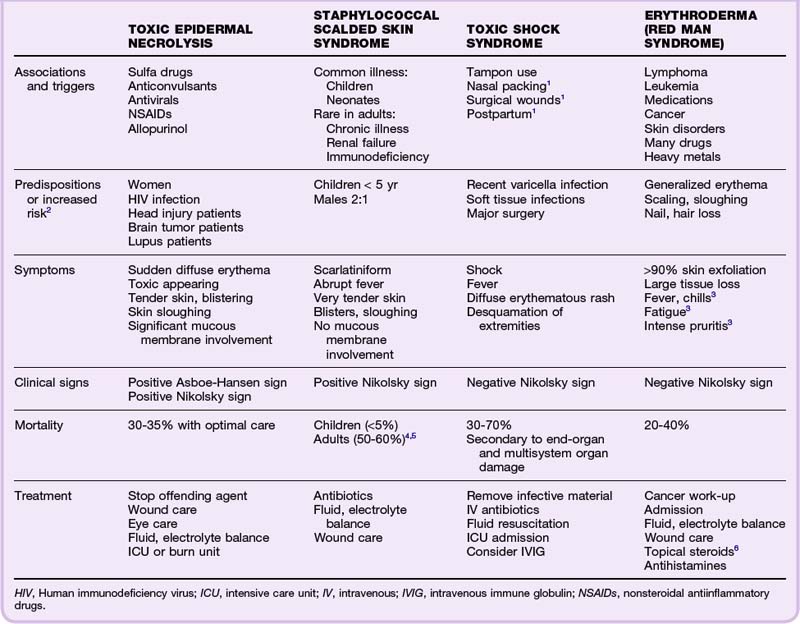

Erythematous Rashes

Toxic patients with an erythematous rash may have specific signs that narrow the differential diagnosis. The combination of an erythematous rash in a toxic patient with a positive Nikolsky sign reduces the differential diagnosis substantially, usually to toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) in adults and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) in infants and young children. Alternatively, the differential diagnosis for toxic and febrile patients with an erythematous rash as well as a negative Nikolsky sign includes toxic shock syndrome (TSS), Kawasaki disease, and erythroderma (see Table 192.3). Table 192.4 details the symptoms, signs, mortality, and treatment of the aforementioned erythematous rashes. SSSS, TSS, and Kawasaki disease are also covered in Chapter 18.

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

TEN (Lyell disease) is the most serious cutaneous drug reaction. It is most commonly associated with sulfa drugs; however, it has other important triggers as well. TEN is manifested as the sudden onset of diffuse erythema with tender skin and blistering. The skin cleavage is full thickness with positive Nikolsky and Asboe-Hansen signs and significant skin sloughing (Fig. 192.1). These patients are toxic and exhibit significant mucous membrane involvement. Symptoms occur first around the eyes, spread caudally (shoulders and upper extremities), and then progress to involve the entire body. Several populations are predisposed to TEN and others are at high risk (see Table 192.4). However, one group deserves expanded mention. It is important to consider that patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who are on a chronic regimen of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis and other polypharmacy have a 1000 times greater risk for TEN than do those without HIV.2,7

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Also known as Ritter disease or dermatitis exfoliativa neonatorum,4 SSSS is manifested as a scarlatiniform, erythematous rash caused by a staphylococcal infection that blisters and sloughs (positive Nikolsky sign). Children younger than 5 years are at highest risk.

Kawasaki Disease

This childhood illness is also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome or infantile polyarteritis. It is a vasculitis of unknown cause, although infective and autoimmune theories abound. It affects many organ systems, including the skin, mucous membranes, lymph nodes, and blood vessels. Diagnostic criteria include high fever for at least 5 days, diffuse erythroderma of the skin, strawberry tongue, significant cervical lymphadenopathy, conjunctival injection, peeling of the fingers and toes, and edema of the extremities.8 Thrombocytosis may also be present. By far the most serious complication is vasculitis of the coronary arteries, which leads to coronary vessel aneurysms, myocarditis, and myocardial infarction (even in the very young). Treatment consists of high-dose aspirin (given immediately), hospitalization with supportive care, and very importantly, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) because Kawasaki disease does not respond to antibiotics.8,9

Erythroderma

Erythroderma, also known as exfoliative dermatitis, is an erythematous, scaling rash that involves more than 90% of the skin.10 Erythroderma is also termed red man syndrome when a primary cause cannot be identified.10 The rash begins as a very generalized erythema. The skin begins to scale and slough, along with nails and hair.11 The skin is inflamed and may lose pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals. This is an overwhelming disease process in which large tissue burdens of exfoliated scales are lost en masse daily; these patients are, in essence, “burn victims.” They have marked increases in skin perfusion and profound temperature dysregulation that result in significant heat loss, increased basal metabolic rate, fluid loss, edema, and hypoalbuminemia.10 Although this disease primarily affects adults, it does occur in younger populations who have other skin or connective tissue disorders (lupus, sarcoid, psoriasis, SSSS, atopic dermatitis, or seborrheic dermatitis). Patients with rapid disease progression usually have a history of cancer or SSSS or an inciting medication reaction. Those with gradual symptomatology generally have a skin disorder history. The work-up for these patients should be conducted in close consultation with a dermatologist, who can aid in identification of the primary lesions, which can be a difficult task. All patients warrant cancer evaluation and treatment of the underlying cause. Laboratory studies include a sedimentation rate, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, HIV testing, skin scrapings, skin biopsies, and wound cultures.6 All patients warrant admission. In pediatric patients, erythroderma and fever are predictors of hypotension and may reflect TSS.12 Systemic steroids are controversial and may worsen psoriasis and SSSS. Recovery is long and recurrences common in the case of red man syndrome. Mortality ranges from 20% to 40% and in many instances is due to factors unrelated to the disease process itself.3,13

Maculopapular Rashes

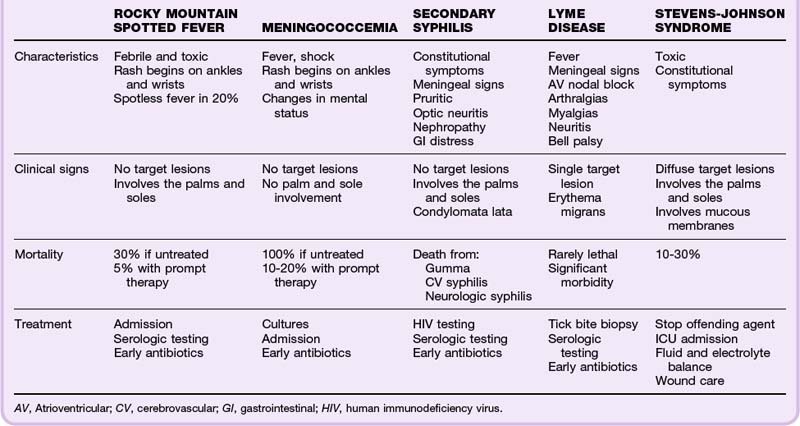

The term maculopapule is a portmanteau of macule and papule. Maculopapular rashes are differentiated according to the distribution of the rash and systemic toxicity (Table 192.5). Patients who appear toxic and febrile have a wide differential diagnosis; however, it is paramount that patients living in endemic areas be assessed for Lyme disease. Target lesions (see Fig. 191.4) are pathognomonic for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and erythema multiforme (EM). Refer to Chapter 191 for review of EM. A full discussion of TEN was presented in the previous section (erythematous rashes); however, TEN and Lyme disease may also be associated with target lesions. Toxic patients with a maculopapular rash but no target lesions require emergency evaluation for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), syphilis, and meningococcemia (see Table 192.3).

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

SJS is often a drug reaction, although infections and malignancies have been implicated. Previously, SJS was thought to be linked with EM, but it has recently been reclassified on the spectrum with TEN.2 These patients have diffusely distributed target lesions that include the palms and soles. Significant mucous membrane involvement is present as well (Fig. 192.2). Patients with SJS are toxic with many constitutional symptoms. Treatment involves discontinuation of the offending agent and optimization of fluid and electrolyte status. Steroid treatment is controversial. Both SJS and TEN have greater mortality (10% and 30%, respectively) than do EM major (mortality less than 5%) and minor (negligible morbidity and mortality). Patients with SJS require intensive care unit (ICU) admission.2,5,8,14–16

Lyme Disease

This tick-borne illness is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. The patient generally has erythema migrans (a large annular target lesion with a dark red border and central clearing) at the site of the tick bite (Fig. 192.3). The rash begins with tick inoculation and may therefore be central or peripheral in location.6 As the infection spreads hematogenously over a period of days to weeks, the patient may experience a variety of systemic symptoms, including a secondary rash (annular lesions), fever, meningitis, atrioventricular nodal block, migratory arthralgias, and myalgias. Neuritis occurs as well and is often manifested as Bell palsy (which may be bilateral); however, any nerve can be affected. The diagnosis is made clinically, although biopsy of the site of the tick bite is often diagnostic. Serologic tests are positive after several weeks but do not differentiate active from inactive infection. Though rarely lethal, Lyme disease can be accompanied by significant morbidity, usually related to neurologic and rheumatic complications. Doxycycline is first-line the treatment in nonpregnant adult patients. Children may be treated with amoxicillin. Ceftriaxone is indicated for those with significant neurologic or cardiac involvement.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

This tick-borne illness (Rickettsia rickettsii) has been recorded from Canada to Mexico and in every mainland state in the union except Vermont and Maine. Although history taking is essential, only 50% can recall a tick bite.1 The RMSF-associated erythematous, maculopapular rash begins on the wrists and ankles and spreads over the entire body (including the palms and soles). In its early stage the rash consists of reddish macules that blanch, only to become petechial and purpuric later. In up to 20% of patients, the rash is absent (spotless fever).1 Regardless of whether the rash is present, these patients are highly febrile and toxic. The diagnosis is clinical! Do not await confirmatory antibody tests to begin treatment (they will be negative in the acute period). These patients may appear to have meningococcemia. If the clinician is unsure of the diagnosis, it is essential to treat for both diseases. Lumbar puncture in a patient with RMSF will show leukocytosis with 25% neutrophils, elevated protein, and low to normal glucose. If not recognized and treated early, the mortality associated with RMFS is higher than 30%. However, mortality decreases to 5% with prompt appropriate antibiotic therapy. The neurologic deficits are permanent in 15% of cases.15,17–20 Doxycycline is the drug of choice in all nonpregnant patients, even children. Pregnant patients may be treated with chloramphenicol, although doxycycline may also be considered in especially sick pregnant patients because chloramphenicol simply does not work as well.1,15,17–20

Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis is an infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Primary syphilis is characterized by a painless chancre (punched-out base with rolled edges).21 It resolves completely and without scar formation in about 3 to 6 weeks. Secondary syphilis develops about 4 to 10 weeks after emergence of the chancre.22 The patient will have many constitutional symptoms: malaise, headache, sore throat, fever, joint and muscle aches, decreased oral intake, meningeal symptoms, generalized lymphadenopathy, and a rash.21,23 The rash of secondary syphilis is maculopapular, symmetric, nonpruritic, and diffuse. It may also involve the palms and soles, as well as the oral mucosa.22,23 Patients may also have other skin findings, including condylomata lata (painless, gray to white verrucous lesions in the groin and other moist regions) and patchy alopecia. These patients can become very ill, with gastrointestinal distress, hepatitis, arthritis, optic neuritis, proctitis, and nephropathy. The diagnosis is made clinically, and a high index of suspicion is required. Testing for HIV is also recommended. The sensitivity of the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests approaches 100% for secondary syphilis.24 Because false-positive testing does occur, confirmatory fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption testing (FTA-ABS) is also performed.24 The sensitivity of FTA-ABS for secondary syphilis also approaches 100%.24 Treatment consists of intramuscular administration of penicillin G for all patients.23 Bicillin LA is preferred over Bicillin CR due to increased concentrations of benzathine penicillin G. Penicillin G is also the only treatment for pregnant women. Pregnant patients with allergies should undergo desensitization and then treatment with penicillin.23 Nonpregnant patients allergic to penicillin may be treated with doxycycline.22

Meningococcemia

Meningococcemia is caused by infection with Neisseria meningitidis, a gram-negative intracellular diplococci that causes fulminant septicemia and has a predilection for adolescents and children younger than 4 years. Without proper treatment, meningococcemia is invariably fatal; mortality remains at 10% to 20% even with immediate therapy.1 Patients are ill appearing, febrile, and in shock and have changes in mental status and a rash that develops within 24 hours of toxicity. The rash is initially erythematous and maculopapular (beginning on the wrists and ankles) and then spreads (sparing the palms and soles) and becomes a petechial vasculitis that is palpable. Early in the illness, meningococcemia can be mistaken for RMSF. Treatment of both is mandatory when there is any diagnostic uncertainty. The diagnosis is confirmed by Gram stain and blood or CSF culture. Gram staining of a specimen from a meningococcal skin lesion is more sensitive than a CSF Gram stain (72% versus 22%, respectively).1 Lumbar puncture in patients with meningitis will show leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils, low glucose, and high protein. Complications include disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, multisystem organ failure, and adrenal hemorrhage (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome). Ceftriaxone is first-line therapy. Vancomycin should be added in cases of diagnostic uncertainty to cover resistant streptococcal meningitis. Dexamethasone has been shown to reduce neurologic sequelae if administered early (before antibiotics, if possible). Rifampin prophylaxis for close contacts is recommended; alternatives include single-dose ciprofloxacin and intramuscular ceftriaxone.1 A vaccine is available and is now recommended routinely for children 11 to 18 years of age.

Vesiculobullous Rashes

Vesiculobullous rashes provoke significant angst in many physicians; however, the differential diagnosis for febrile and toxic patients can be greatly simplified by discerning whether the rash is localized or diffuse. Ill patients with a diffuse vesiculobullous rash and a fever may have varicella or a more devastating illness such as smallpox or purpura fulminans/DIC. Toxic patients with localizing lesions require evaluation for necrotizing fasciitis (see Table 192.3).

Necrotizing Fasciitis

This acutely toxic disease is caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci and may also be synergistic with Staphylococcus aureus, Vibrio vulnificus, anaerobes, or polymicrobial infections.25 Predisposing factors include intravenous drug use, diabetes, malignancy, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, alcoholism, and other immunosuppressive states.25,26 Importantly, these patients have pain out of proportion to the findings on examination and more toxicity than typical for cellulitic disease. Hemorrhagic bullae are often evident superficially, and the disease spreads rapidly along fascial planes. Crepitation may be present and can be seen as subcutaneous gas on radiographs. Treatment is prompt surgical débridement and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy has also been shown to significantly reduce mortality and amputation rates in these patients.27 Mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis ranges from 0% to 75% (average mortality, 35%) and is dependent on the infective organisms, patient population, treatment protocols, and resources (including the availability of hyperbaric oxygen therapy).

Varicella

Chickenpox (varicella-zoster virus or herpesvirus 3) is usually a benign, self-limited infection with an incubation period of 10 to 21 days. Infectivity is present 48 hours before the onset of fever and continues until all lesions have crusted.28 Symptoms include conjunctival and catarrhal manifestations followed by a rash.28,29 The rash appears in various stages at same time (papules, vesicles, crusted) and is described historically as “dew drops on a rose petal.”28 Children should not be given aspirin for fever because of concerns related to Reye syndrome. All patients should avoid those who are pregnant, elderly, or immunocompromised. Complications from varicella include staphylococcal or streptococcal secondary infections, visceral complications (15% mortality rate in the immunocompromised), neurologic complications (most common in children), pneumonia (most common in adults), and perinatal varicella (30% mortality rate).28–32 Prevention involves immunization, which decreases the rate of occurrence and severity. Please refer to Chapter 18 for further review of varicella.

Smallpox

Few differential considerations invoke more fear or dread than smallpox. Although smallpox was eradicated in 1980, isolates still exist in the United States and Russia.33 Moreover, nearly 50% of the U.S. population has never been vaccinated against smallpox. Infection by the variola virus is manifested in two forms (major and minor), and only humans are infected (no carrier state). It is spread by inhalation or direct contact. Infection results in a silent viremia for 2 weeks, followed by the sudden onset of fever, severe headache, nausea, malaise, and a sore throat.33,34 During this time an enanthem that is fine, erythematous, and macular may be found on the posterior pharynx, soft palate, and tongue.35 It is followed by the exanthem, which begins on the face and spreads centrifugally to encompass the entire body (including the palms and soles in 50%) within 24 hours. These lesions start as macules, then papules, and finally pustules that crust over in several weeks. The lesions are always in the same stage of development. Any suspected cases should be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at once. Vaccinated personnel should obtain viral swabs of the patient’s throat or pustular skin lesions. Strict respiratory and contact isolation is mandatory. Supportive care with attention to eye care (keratitis) is indicated. The mortality rate positively correlates with the extent of the rash (10% to 80%; mean, 30%).33 Death usually occurs as a result of overwhelming toxemia. Complications include blindness and diffuse scarring.

Purpura Fulminans/Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy

This acutely life-threatening disorder is associated with previous infection (often meningococcus or gram-negative organisms), sepsis, pregnancy, massive trauma, end-stage malignant disease, hepatic failure, snake bites, transfusion reactions, or anything that can precipitate DIC. It is characterized by fever, shock, rapid subcutaneous hemorrhage (ecchymotic purpura, hemorrhagic bullae), tissue necrosis, widespread petechiae, bleeding from multiple sites, widespread organ failure, and DIC (Fig. 192.4). The pathophysiology of this disease spectrum involves activation of the coagulation cascade with thrombin and fibrin formation. This leads to occlusion of vessels and end-organ damage with the consumption of platelets and clotting factors. Overactivation of the fibrinolytic system then occurs with resultant endogenous fibrinopeptide A production and bleeding. Laboratory findings include thrombocytopenia, schistocytes, prolongation of the prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), increases in fibrin degradation products and D-dimer levels, and a decrease in fibrinogen levels. The lower the fibrinogen levels, the higher the mortality. Emergency hematology/oncology consultation and ICU admission are mandatory. First-line therapy is treatment of the underlying cause. Folate, vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), cryoprecipitate, platelets, and red blood cell transfusions are given as needed; heparin is also used for associated thrombi. Antithrombin III is a promising investigational drug but has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A metaanalysis of trials showed a reduction in mortality from 47% to 32% with the administration of antithrombin. Knowing when to use each of these agents is a tricky balancing act and is best done in consultation with a hematologist.36,37

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes

These rashes can be especially challenging and are associated with devastating differential diagnoses. However, an algorithmic approach can help the physician narrow the diagnosis with confidence (see Table 192.3). It is helpful to determine early whether the rash is palpable or nonpalpable. Palpable (raised) purpura occurs in vasculitic diseases secondary to inflammation or infection. In toxic and febrile patients with palpable petechial/purpuric lesions, the differential diagnoses includes RMSF, endocarditis, and meningococcemia. Nonpalpable purpura (flat, subcutaneous hemorrhages) occurs in thrombocytopenic conditions. Toxic and febrile patients with petechiae or purpura but without palpable lesions may have purpura fulminans/DIC or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

Bacteremic Endocarditis

Endocarditis is a systemic infectious process caused most commonly by Streptococcus viridans, coagulase-negative staphylococci, and S. aureus.38 Patients with endocarditis have various constitutional symptoms that mimic other diseases (tuberculosis, heart failure, and malignancy). Early in its course, patients may not appear to be toxic. However, the symptoms progress to fever, new cardiac murmur, weakness, anemia, fatigue, malaise, weight loss, and rash. Risk factors include valvular disorders, intravenous drug use, immunodeficiency, dialysis, poor dental hygiene, and chronic in-dwelling vascular access.39 Associated skin findings are pathognomonic and include petechiae (most common finding and may involve the eyelids and conjunctiva), Roth spots (exudative, edematous hemorrhagic retinal septic emboli), splinter hemorrhages, Janeway lesions (macular erythematous or hemorrhagic spots on the palms and soles), and Osler nodes (painful, violaceous nodules in the pulp pads of finger and toes).40 The diagnosis is confirmed with transesophageal echocardiography and by identification of valvular vegetations. Treatment consists of broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and, thereafter, guidance by culture of blood (three sets) obtained before antibiotic therapy. Endocarditis is associated with significant morbidity; mortality is 25% to 40% for S. aureus endocarditis and 19% for S. viridans endocarditis.

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Patients with TTP have fever, jaundice, and a diffuse, nonpalpable petechial/purpuric rash in a distinct manifestation. The classic pentad of symptoms includes fever, thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, neurologic deficits, and renal failure. It is more common, however, to observe the clinical triad of thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase. This triad of findings alone is sufficient for the diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Numerous conditions are associated with TTP, including HIV infection, lupus, pregnancy, malignancy, and transplantation. Drugs associated with TTP include clopidogrel, cyclosporine, and quinine. Laboratory studies reveal that unlike DIC, the PT, PTT, and fibrin level are often normal. Schistocytes and helmets cells are seen on blood smears and indicate hemolysis. The pathophysiology of TTP involves platelet aggregation and thrombus formation with diffuse organ and tissue damage. Treatment includes emergency hematology/oncology consultation, plasmapheresis, FFP, ICU admission, and treatment of the underlying cause. Importantly, FFP can be used as a temporizing measure, but patients with TTP should be transferred to a facility with the capability of performing plasmapheresis. Platelet administration is to be avoided because it will precipitate more thrombus formation.41 The mortality associated with TTP is higher than 90% if not properly treated. Exchange transfusion can decrease the mortality to 10%.41,42 Facilities without the ability to perform exchange transfusions must consider emergency transfer to an appropriate facility.

Treatment

Erythematous Rashes

Treatment of these rashes can be found in Table 192.4. These highly lethal rashes require intensive treatment and continuous monitoring for complications. Patients with TEN may benefit from IVIG, although this indication is not yet approved by the FDA. Most physicians recommend against steroid use. Sulfadiazine should not be used on the wounds because sulfa is the most common offending agent.43 Treatment of SSSS in young, well-appearing patients with minimal skin sloughing may be conducted on an outpatient basis (mortality < 5%). By contrast, adult SSSS has a mortality that can be as high as 60%.4,5 Treatment of Kawasaki disease involves hospitalization, supportive care, and immediate high-dose aspirin to prevent coronary artery vasculitis, coronary vessel aneurysms, myocarditis, and myocardial infarction. Importantly, IVIG must be administered because Kawasaki disease does not respond to antibiotics.9,10 Treatment of erythroderma involves recognition that recovery is long and recurrences common.

Maculopapular Rashes

Treatment of these rashes can be found in Table 192.5. Though rarely lethal, Lyme disease can be associated with significant morbidity, usually related to neurologic and rheumatic complications. Doxycycline is the first-line treatment of Lyme disease in nonpregnant adult patients. Children may be treated with amoxicillin. Ceftriaxone is indicated for those with significant neurologic or cardiac involvement. Treatment of RMSF consists of doxycycline. It is the drug of choice in all nonpregnant patients, even children. Pregnant patients may be treated with chloramphenicol, although doxycycline may also be considered in especially sick pregnant patients because chloramphenicol simply does not work as well.1,15,17–20 Patients with SJS are toxic and have many constitutional symptoms, but the use of steroids is controversial at this time. Meningococcemia is a dreaded disease with many complications. Ceftriaxone is first-line therapy. Vancomycin should be added in cases of diagnostic uncertainty to cover resistant streptococcal meningitis. Dexamethasone reduces neurologic sequelae if administered early.

Vessiculobullous Rashes

Treatment of necrotizing fasciitis involves prompt surgical débridement, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and fluid resuscitation. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy significantly reduces mortality and amputation rates.27 Varicella is a self-limited illness in most patients, although complications can be devastating. Treatment of varicella is reviewed in Chapter 18. Smallpox is a devastating illness whose care is primarily supportive, with attention to eye care for keratitis. Death usually occurs as a result of overwhelming toxemia. In a similar manner, purpura fulminans is a disease with high morbidity and mortality. First-line therapy involves treatment of the underlying cause and administration of blood products (FFP, cryoprecipitate, platelets, and red blood cells). Folate, vitamin K, and heparin are also given. Antithrombin III is a promising investigational drug that has not yet been approved by the FDA. A metaanalysis of trials showed a reduction in mortality from 47% to 32% with the administration of antithrombin. Hematologist consultation is essential.36,37

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes

Treatment of RMSF, meningococcemia, and purpura fulminans was discussed in a previous section. Bacterial endocarditis is a disease that requires consultation with cardiology and infectious disease specialists. Treatment consists of broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover MRSA and, thereafter, guidance by culture of blood (three sets) obtained before antibiotic therapy. Treatment of TTP includes ICU admission, emergency hematology consultation, plasmapheresis, FFP, and treatment of the underlying cause. Importantly, FFP is only a temporizing measure. Patients must be treated definitively with plasmapheresis (exchange transfusion) or be transferred. Platelet administration will precipitate more thrombus formation.41,42

Follow-Up and Patient Education

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes

Tips and Tricks

Drug reactions: Stop the offending agent and all related compounds at once. This will reduce the risk for death by 30% daily!

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: Usually caused by drugs.

Endocarditis, meningococcemia, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever: May be manifested as either a maculopapular (early) or petechial/purpuric rash (late) morphology. Serial examinations are mandatory!

Meningitis: The gold standard for diagnosis is cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Meningitis prophylaxis: Should be given to close contacts, including classmates, household members, and medical personnel who had contact with respiratory droplets.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever: Doxycycline is the drug of choice, even in children. Pregnant patients may be treated with chloramphenicol, but doxycycline should be considered if the patient is especially ill.

Meningitis versus Rocky Mountain spotted fever: If the diagnosis is not clear, treat both!

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: 80% have an associated skin or soft tissue infection. Look for it early because drainage is a critical component of treatment.

Necrotizing fasciitis: Pain out of proportion to findings on examination. Always complete a full genitourinary examination on all ill-appearing patients because many are too toxic to adequately relate symptoms.

Fingers and toes: Must be evaluated for signs of endocarditis (Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, splinter hemorrhages).

Tissue samples: Can be of immense value in certain instances. Tzanck smears are sensitive for herpes infections. Potassium hydroxide preparations can identify yeast infections. Gram stains will identify gonococcals and anthrax organisms. Punch biopsies with a Gram stain will aid in the identification of meningococcemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Carr DR, Houshmand E, Heffernan MP. Approach to the acute, generalized, blistering patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:139–146.

Mukasa Y, Craven N. Management of toxic epidermal necrolysis and related syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:60–65.

Murphy-Lavoie H, LeGros T. Emergent diagnosis of the unknown rash, the algorithmic approach. Emerg Med. 2010;42(3):6–17.

Nguyen T, Freedman J. Dermatologic emergencies: diagnosing and managing life-threatening rashes. Emerg Med Pract. 2002;4(9):1–28.

Rothe MJ, Bernstein ML, Grant-Kels JM. Life-threatening erythroderma: diagnosing and treating the “red man.”. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:206–217.

1 Nguyen T, Freedman J. Dermatologic emergencies: diagnosing and managing life-threatening rashes. Emerg Med Pract. 2002;4(9):1–28.

2 Mukasa Y, Craven N. Management of toxic epidermal necrolysis and related syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:60–65.

3 Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Hezemans-Boer M, et al. Erythroderma. A clinical and follow-up study of 102 patients, with special emphasis on survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:53–57.

4 Margileth AM. Scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and management of 42 children. South Med J. 1975;68:447–454.

5 Carr DR, Houshmand E, Heffernan MP. Approach to the acute, generalized, blistering patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:139–146.

6 Rothe MJ, Bernstein ML, Grant-Kels JM. Life-threatening erythroderma: diagnosing and treating the “red man.”. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:206–217.

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 2008-1250, August 2008. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Emergency Department Summary. National Health Statistics Report. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr007.pdf, 2010. Accessed February 16

8 Hom C. Vasculitis and thrombophlebitis. eMedicine. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1008239-overview Updated November 23, 2009. Accessed January 10, 2010

9 Yamamoto LG. Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:422–424.

10 Bruno TF, Grewal P. Erythroderma: a dermatologic emergency. CJEM. 2009;11:244–246.

11 Botella-Estrada R, Sanmartin O, Oliver V, et al. Erythroderma: a clinicopathological study of 56 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1503–1507.

12 Byer RL, Bachur RG. Clinical deterioration among patients with fever and erythroderma. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2450–2460.

13 Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA. Idiopathic erythroderma: a follow-up study of 28 patients. Dermatology. 1997;194:98–101.

14 Wolf R, Matz H, Marcos B, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms vs toxic epidermal necrolysis: the dilemma of classification. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:311–314.

15 Chapman AS, Murphy SM, Demma LJ, et al. Rocky mountain spotted fever in the United States, 1997-2002. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:154–155.

16 Ghislain PD, Roujeau JC. Treatment of severe drug reactions: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and hypersensitivity syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8(1):5.

17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in family clusters—three states, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(19):407–410.

18 Archibald LK, Sexton DJ. Long-term sequelae of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1122–1125.

19 Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, Schutze GE, et al. Clinical and laboratory features, hospital course, and outcome of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children. J Pediatr. 2007;150:180–184.

20 Davis BP, Marx JA. An evidence-based approach to the diagnosis and treatment of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2007;9(3):1–24.

21 Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187–209.

22 Romanelli F, Kent ME. Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:226–236.

23 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–109.

24 Calonge N. Screening for syphilis infection: recommendation statement. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:362–365.

25 Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1454–1460.

26 Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, Gunter R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los Angeles. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1445–1453.

27 Escobar SJ, Slade JB, Jr., Hunt TK, et al. Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO2) for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis reduces mortality and amputation rate. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2005;32:437–443.

28 Heininger U, Seward JF. Varicella. Lancet. 2007;369:1365–1376.

29 Daley AJ, Thorpe S, Garland S. Varicella and the pregnant woman: prevention and management. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:26–33.

30 Lampell M. Childhood rashes that presents to the ED. Part 1: viral and bacterial issues. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 3, 2007. Available on Ebmedicine.net

31 Seward JF. Update on varicella. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:619–622.

32 Gnann JW. Varicella-zoster virus: atypical presentations and unusual complications. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(Suppl 1):S91–S98.

33 Paran N, Sutter G. Smallpox vaccines: new formulations and revised strategies for vaccination. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:824–831.

34 Parrino J, Graham G. Smallpox vaccines: past, present, and future. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1320–1326.

35 Kman NE, Nelson RN. Infectious agents of bioterrorism: a review for emergency physicians. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26:517–547. x-xi

36 Levi M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2191–2195.

37 Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T, et al. Novel approaches to the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(Suppl 9):20S–24S.

38 Moreillon P, Que YA. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2004;363:139–149.

39 Hoen B. Epidemiology and antibiotic treatment of infective endocarditis: an update. Heart. 2006;92:1694–1700.

40 Westphal N, Plicht B, Naber C. Infective endocarditis—prophylaxis, diagnostic criteria, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:481–489.

41 Sarode R. Atypical presentations of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a review. J Clin Apher. 2009;24:47–52.

42 Symonette D. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. eMedicine. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/779969-overview, 2009. Accessed February 13, 2010 Updated September 16

43 Chia FL, Leong KP. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:304–309.