Radiological differential diagnosis – describing a lesion

Introduction

As a result, many of these pathological conditions resemble one another closely. This often creates considerable confusion. Fortunately, the sites where the lesions develop, how they grow and the effects they have on adjacent structures tend to follow recognizable patterns. As mentioned in Chapter 19, it is the recognition of these particular patterns that provides the key to interpretation and the formation of a radiological differential diagnosis.

Detailed description of a lesion

Site or anatomical position

This should be stated precisely, for example the lesion(s) could be:

• Localized to the mandible, affecting:

• Localized to the maxilla, affecting:

• Originating from a point or epicentre relative to surrounding structures, e.g.:

In the mandible, so-called odontogenic lesions develop above the inferior dental canal, while non-odontogenic lesions develop above, within or below the canal. Thus some conditions have a predilection for certain areas whilst others develop in one site only. For example, radicular dental cysts develop at the apices of non-vital teeth, while so-called fissural bone cysts develop only in the midline. The site or anatomical position of a lesion may therefore provide the initial clue as to its identity.

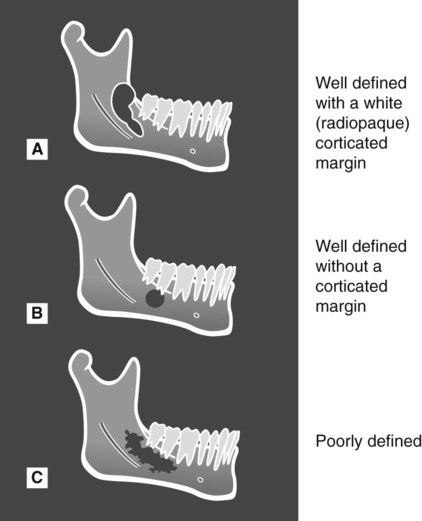

Outline/edge or periphery

The outline or periphery of lesions is described conventionally as being discrete and well defined or non-discrete and poorly defined and as having various additional characteristics (see Fig. 25.3).

Relative radiodensity and internal structure

The radiodensity of the lesion should be assessed relative to the surrounding tissues. Radiolucent lesions are only evident within otherwise hard (radiopaque) tissues as a result of a decrease in mineralization, resorption of mineralized tissue or a decrease in thickness. As stated in Chapter 2, the amount of photoelectric absorption and hence opaque/whiteness of a structure is ∝ Z3. The atomic number (Z) of bone is approximately 12 (Z3 = 1728), whereas the atomic number of soft tissue is approximately 7 (Z3 = 343). A soft-tissue lesion replacing bone will therefore appear radiolucent.

Radiopaque lesions are evident in bone because of an increase in mineralization, increase in thickness, or superimposition on some other structure. They are also evident following calcification in soft tissues (see Ch. 27), having replaced air in the maxillary antra (see Ch. 28) or as a result of an increase in thickness of either normal or abnormal soft tissue.

Thus, relative to the surrounding tissues, the radiodensity of the lesion could be:

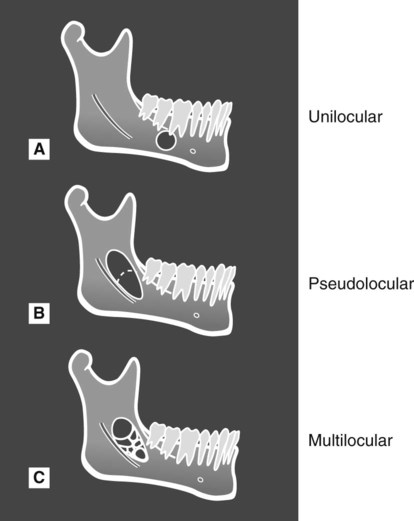

The relative radiodensity also helps in the differentiating process by highlighting the internal structure of partially or completely radiopaque lesions. The alternatives include:

• Fine bone trabeculae, e.g. ground glass appearance

• Thick, coarse trabeculae with enlarged trabecular spaces, e.g. honeycomb appearance

• Haphazard sclerotic bone, e.g. cottonwool patches

• Homogeneous dense cortical bone

• Discrete bony septa, which could be:

• Cementum – oval or round amorphous calcification

Effects on adjacent surrounding structures

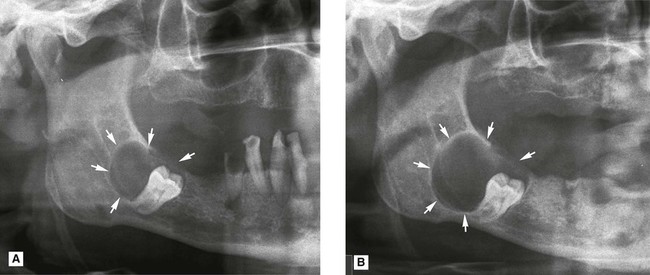

The following structures need to be checked (see Fig. 25.4):

The teeth

• Resorption, which is a feature of long-standing, benign but locally aggressive lesions, chronic inflammatory lesions, and malignancy

• Disrupted development, resulting in abnormal shape and/or density

• Loss of associated lamina dura

• Increase in the width of the periodontal ligament space

Surrounding bone

• Displacement or involvement of surrounding structures, including the:

• Increased density (sclerosis)

• Subperiosteal new bone formation

• An increase in the normal width of the inferior dental canal

• Irregular bone remodelling, resulting in an abnormal shape or unusual overall bone pattern.

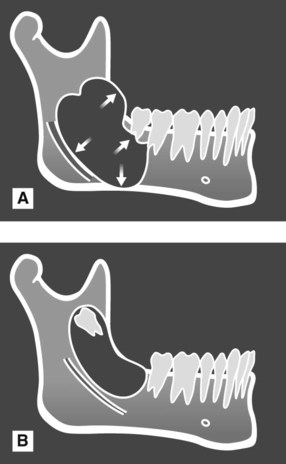

Time present

The length of time the lesion has been present – days, weeks or years – should be determined, if possible. Unfortunately, this information is not always available. The patient may not be aware of the lesion and there may be no records of when it first became evident. If sequential radiographs are available, they can be very useful in providing information on the speed of growth, or development, of a lesion (see Fig. 25.5). This in turn may provide a clue about the nature of the lesion because slow-growing lesions tend to be benign, whilst fast-growing, aggressive lesions are usually malignant.

Footnote

This methodical, systematic description of the features of a lesion forms the basis of the step-by-step differential diagnostic process and is used throughout Chapters 26 and 27. As is shown later, several of the same features are shared by different conditions. Thus, no one feature alone gives enough information to provide the diagnosis. All the features should be considered carefully to determine their relevance and importance.

To access the self assessment questions for this chapter please go to www.whaitesessentialsdentalradiography.com

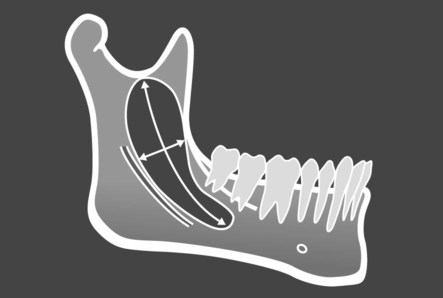

up to the sigmoid notch, and from the anterior border of the ramus down to the ID canal,’ or ‘It is approximately 6 cm × 2 cm’.

up to the sigmoid notch, and from the anterior border of the ramus down to the ID canal,’ or ‘It is approximately 6 cm × 2 cm’.