CHAPTER 93 Radiofrequency Denervation

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain is ubiquitous to mankind by virtue of our upright posture. Traditionally, it has been believed that most episodes of spinal pain are short lived and that at least 90% of patients with low back pain recover in about 6 weeks with or without treatment.1–3

Contrary to this prior assumption of only 10–20% patients experiencing recurrent or chronic symptoms after an initial episode of low back pain, recent literature puts that number as high as 35–79%.4–7

The challenge lies, in this subgroup of subjects, to identify the specific pain generator so that appropriate interventional therapy may be initiated as and when indicated. The study by Kuslich et al.8 identified along with intervertebral disc, dura, ligaments, fascia, and muscles, zygapophyseal or facet joints as capable of transmitting pain in the low back region. Even prior to this anatomical study, Goldthwait9 in 1911 first recognized lumbar zygapophyseal joints as potential source of low back pain. He believed that joint asymmetry could result in pain secondary from nerve root pressure. Subsequently, in 1933, Ghormley10 first coined the term ‘facet syndrome’ as lumbosacral pain with or without sciatic pain, occurring after a twisting or rotary strain of the lumbosacral region. Badgley11 in 1941 suggested that facet joints by themselves could be a primary source of low back pain separate from the nerve compression component. However, it was not until 1963 when Hirsch et al.12 demonstrated that the low back pain distributed along the sacroiliac and gluteal areas with referral to the greater trochanter could be induced by injecting hypertonic saline in the region of the lumbar facet joints. In 1976, Mooney and Robertson,13 and three years later McCall et al.14 used fluoroscopy to confirm the location of intra-articular lumbar facet joint injections in asymptomatic individuals, demonstrating reproduction of back and leg pain after injection of hypertonic saline. Eventually, Marks15 in 1989, followed by Fukui et al.16 in 1997, described the distribution of pain patterns after stimulating the lumbar facet joints.

Recent literature17 indicates that the prevalence of chronic lumbar zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain has a wide range that varies from 15% in the relatively younger patients, with confidence limits of 10–20%. This prevalence can be as high as 40% among the elderly population with confidence limits of 27–53%.18

ANATOMY

The lumbar facet or zygapophyseal joints are paired, true synovial, diarthrodial joints that form the posterior aspect of the respective intervertebral foramina. The joint consists of hyaline cartilage, a synovial membrane, a fibrous capsule, and nociceptive fibers transmitted via the medial branches of the dorsal rami.19,20 These facet joints are innervated by the medial branches of the dorsal rami (posterior primary rami) that exit the intervertebral foramina. The posterior primary rami travel posteriorly over the base of the transverse process. The dorsal ramus divides into a medial, an intermediate, and a lateral branch. The lateral branch ascends from the dorsal ramus just before it reaches the transverse process. The medial branch passes under the mammilloaccessory ligament and sends branches to the adjacent facet joint, the facet joint below, and the more medial erector spinae muscles. Thus, the joint is typically innervated from a branch at the same level and a branch originating from the foramen above. In contrast, the dorsal ramus at the fifth lumbar vertebral level (L5) travels between the ala of the sacrum and its superior articular process, which divides into the medial and lateral branches at the caudal edge of the process, the medial branch continuing medially, where it innervates the lumbosacral joint.21–23

Neuroanatomical studies12,24–26 indicate that the facet joint capsule is richly innervated, containing both free and encapsulated endings, and can undergo extensive stretch under physiological loading.27 It has been reported that protein gene product (PGP) 9.5, substance P (SP), calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), neural peptide Y (NPY), and choline acetyl transferase (chAT) immunoreactive (IR) fibers are present within the human facet joint capsule.21,26,28–30 Ashton et al.31 confirmed immunoreactivity for SP, CGRP, and VIP in surgically removed human facet joint capsule. A subsequent anatomical study confirmed higher concentration of inflammatory cytokines in facet joint tissue from patients with lumbar spinal stenosis than in lumbar disc herniations, suggesting that these cytokines may have some contribution to the etiology of symptoms in degenerative spinal stenosis.32

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

With aging, the changes that occur in the zygapophyseal joints are the same as those seen in any diarthrodial joint. The earliest change is synovitis, which may persist with the formation of a synovial fold which projects into the joint space itself. Later, degenerative changes set in gradually, and eventually become more marked. Eventually, the capsular laxity allows for subluxation of the joint surfaces. Continued degeneration mainly due to repeated torsional strains results in the formation of subperiosteal osteophytes, and possibly subchondral synovial cysts. The end result is that of gross articular degeneration, with almost complete loss of articular cartilage, and formation of bulbous zygapophyseal joints and marked periarticular fibrosis. The pathogenesis of a degenerative cascade in the context of a three-joint complex involving the intervertebral disc and the adjacent zygapophyseal joint also leads to the assumption that the degenerative changes within the disc are also believed to lead to associated facet degeneration.33–35

PAIN PATTERNS

The clinical presentation of lumbar zygapophyseal joint-mediated low back pain appears to overlap considerably with the presentation of low back pain due to various other etiologies. Lumbar facet joints have been shown to be capable of producing pain in the low back and referred pain in the lower extremity in normal volunteers.13–16 McCall et al.14 concluded that pain referral patterns overlap between the upper and lower lumbar spine. Marks15 also studied patterns of pain induced from lumbar facet joints, from the posterior primary rami of L5, and from the medial articular branches of the posterior primary rami from T11 to L4. He observed no consistent segmental or somatic referral pattern. Marks also concluded that pain referred to the buttocks or trochanteric region occurred mostly from the L4 and L5 levels, while inguinal or groin pain was produced from L2 to L5. This latter finding led to the conclusion that the nerves innervating the joints gave rise to distal referral of pain more commonly than the facet joint itself. Fukui et al.16 concluded that the major site of referral pain from the L1–2 to L4–5 joints was the lumbar region itself. However, stimulation of the L5–S1 joint caused referred spinal pain as well as gluteal pain. Referred pain into the lower extremities was not observed by Fukui et al.16 as was reported by Mooney and Robertson.13 However, it must not be overlooked that in the study by Mooney and Robertson, the relatively large volume of the injectate (3 cc) used may very well have inadvertently anesthetized structures other than the facet joint intended. In essence, these studies indicate that there is no clear dermatomal or somatic pattern that is diagnostic of lumbar facet joint-mediated pain and an overlap with a varied pattern is the norm.

DIAGNOSIS

All this being said, there is no identified correlation between a clinical picture or any imaging study used, such as the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), or radionuclide bone scan in diagnosing pain mediated via the lumbar zygapophyseal joint.36–40 Simple static radiographs of the lumbar spine, and also dynamic images including standing flexion–extension films, may reveal evidence of arthritis involving the lumbar zygapophyseal joint as commonly in asymptomatic individuals as in patients with axial low back pain. What remains contentious is how lumbar zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain should be diagnosed.

Diagnostic injections

The only available means of establishing a diagnosis of lumbosacral zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain is to utilize diagnostic injections. Diagnostic blockade of a structure with a nerve supply with ability to generate pain can be performed to test the hypothesis that the target structure is the source of symptoms. If pain is relieved by blocking the medial branch or the zygapophyseal joint itself, the joint may be considered prima facie to be the source of pain.41 Pain relief is considered as the essential criterion, rather than provocation of pain from stimulating the target area.

The choice lies with the spine interventionist whether to pursue an intra-articular zygapophyseal joint injection or anesthetize the medial branches of the dorsal rami that innervate the target joint. Debate continues regarding the appropriateness of intra-articular injections or medial branch blocks. For diagnostic intra-articular injection only a small volume (0.5–0.8 cc) of the local anesthetic agent is to be injected. Using small aliquots of local anesthetic will minimize extravasation of the anesthetic agent and necessarily diminish the frequency of a false-positive response. In essence the specificity of the diagnostic injection is enhanced. A small amount (0.2 cc) of contrast medium should be instilled to ensure an intra-articular spread. A partial arthrogram ensures appropriate needle placement and protects against false appreciation of joint entry and venous infiltration.42 Similarly, when a medial branch block is performed, contrast should be instilled prior to the actual injection of the anesthetic agent to ensure against venous uptake. Theoretically, medial branch injections may be more specific because there is a less likelihood of anesthetizing the epidural space or the neural foramina as long as the anesthetic volume is limited to 0.5 cc. The author prefers to peruse an intra-articular injection in the younger patient population where the joint is not affected by significant arthritis. A medial branch block is preferred in the elderly where it may be technically difficult to access the severely arthritic zygapophyseal joint or when lack of adequate joint space is suspected. Kaplan et al.43 did find that medial branch blocks can fail to anesthetize the target joint in a minority of cases, ostensibly in 11% but possibly in as many as 31%, based on 95% confidence interval intervals. These authors have postulated that an aberrant or additional innervation of the targeted joint may provide for a pathway for persistent nociception. While not refuting the ability of the medial branch blocks to positively diagnose zygapophyseal joint pain, they warn that facet joint pain may be underdiagnosed by such diagnostic blocks.

Based on the response to a single diagnostic injection, the prevalence of the lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain in patients with chronic low back pain demonstrates a wide range of 7.7–75%.42,44–50 This wide range in numbers may represent a selection bias, variable population subsets, or even placebo responders. Similarly, a diagnosis cannot be made reliably on the basis of a single diagnostic injection, and false-positive rates as high as 38% have been demonstrated.51 To increase the sensitivity of these diagnostic injections it has been suggested that controlled diagnostic injection should include placebo injections utilizing normal saline.41 This may be accurate theoretically but is not practically viable, logistical, or ethical to use placebo injections in all patients presenting with low back pain presumably of lumbar facet origin. An attractive, reasonable alternative is the use of comparative local anesthetic blocks using two local agents with different duration of actions on two separate occasions.52–55

From anatomical studies of the innervation of the facet joint it is clear that the medial branch of the dorsal ramus supplies sensory innervation to the joint. Radiofrequency neurotomy of medial branch of the dorsal ramus eliminates this sensory input for a considerably longer duration of time as compared with simple medial branch block and may be used in patients with the goal of achieving long-lasting pain relief.56

REVIEW OF LITERATURE SUPPORTING CLINICAL EFFECTIVENESS OF LUMBAR RADIOFREQUENCY

Historically, interventional management of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain started with the use of a knife-cut in the region of the lumbar facet joint for denervation. Rees57 reported immediate relief of pain in 998 of 1000 patients suffering from ‘intervertebral disc syndrome’ using this technique. Shealy58,59 introduced the procedure in North America but, after a large number of operations, changed to a radiofrequency coagulation lesion through a probe placed in the region of the nerve supply of the facet joint.

Many investigators have studied the effectiveness of radiofrequency denervation of medial branches of the lumbar zygapophyseal joint, of which only four are prospective studies. These include two randomized, controlled trials by van Kleef et al.60 and Leclaire et al.,61 one double-blind, controlled study by Gallagher et al.,62 and a case series by Dreyfuss et al.55 In each of these studies, patients were included when they had failed to respond to traditional conservative treatment, such as a trial of bed rest, medications, and physical therapy. However, the inclusion or exclusion criteria were inconsistent across the studies.

Gallagher et al.62 included patients with low back pain for at least 3 months and used diagnostic injections of 0.5 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine in and around the lumbar zygapophyseal joint. Patients with good or equivocal response to this injection within 12 hours were randomized to undergo either a lumbar facet joint denervation or placebo treatment. Radiofrequency lesions were performed for 90 seconds at a temperature of 80°C. McGill pain questionnaire63 and the visual analog scale (VAS)64 were used at 1 month but only the VAS at 6 months. Statistical comparison of pain scores was conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann Whitney U tests. Reduction in pain scores was approximately 50% at 1 month and was sustained at 6 months. The only difference in pain scores were seen when comparing people, all of whom met the inclusion criteria of a good response to an initial injection using 0.5 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine. The only statistical differences in pain scores in the post-treatment group occurred during comparing patients with a good initial response to local anesthetic injection but proceeding to a sham procedure.

The randomized, controlled trial of van Kleef et al.60 included 31 patients with low back pain of at least 12 months. These were injected with 0.75 cc of 1% lidocaine about the two medial branches innervating a particular zygapophyseal joint. Patients were evaluated 30 minutes after this injection. Those with at least a 50% relief on a four-point Likert scale (0–30% pain relief was considered as no relief; 30–50% was defined as moderate; 50–80% pain relief was good, and 80% or more was considered as pain free) were randomized. Radiofrequency probes were placed in both groups but only one group underwent the actual radiofrequency lesioning for 60 seconds. Patients were followed for at least 12 months and the outcome measures included the VAS instrument, Oswestry disability index, and global perceived effect. At 8 weeks, a higher rate of success in the treatment group compared to the control group was noted. Subsequent log rank test showed a statistically significant difference (p=0.02) at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Leclaire et al.61 performed a diagnostic intra-articular facet joint block with 0.5 cc of lidocaine 2% and 0.5 cc of 40 mg of triamcinolone acetonide. Significant relief of low back pain for at least 24 hours in the week after this injection was considered as positive. For each nerve, radiofrequency neurotomy was performed at two locations, one at the proximal portion and another at the distal portion of the dorsal ramus with the temperature controlled at 80°C for 90 seconds. For patients in the control group the temperature of the probe was maintained at 37°C. Follow-up assessments were undertaken at 4 and 12 weeks when the disability questionnaire, the visual analog scale, the triaxial dynamometry, and the return to work assessment was repeated. The primary analysis was based on the intention to treat principle. At the end of 4 weeks, there was an improvement in the Roland-Morris score65 by 8.4% and 2.2% in the radiofrequency and control groups, respectively. However, at 12 weeks there was no significant difference in the Roland-Morris,65 Oswestry disability,66 VAS,64 strength/mobility, and return-to-work status in both groups.

Dreyfuss et al.55 used 0.5 cc of lidocaine 2% for the initial zygapophyseal joint injection. A positive response was defined as at least 80% relief of pain lasting longer than 1 hour. At the end of 1 week, this group of patients underwent another diagnostic injection using bupivacaine 0.5%. Subjects experiencing greater than 80% relief, lasting longer than 2 hours, were included in the study. The technique used by Dreyfuss et al.55 was different in that the radiofrequency ablation was performed for 8–10 mm along the length of the target nerve with the temperature being maintained at 85°C. The outcome measures included VAS,64 Roland-Morris questionnaire,65 prescription analgesic medication, McGill pain questionnaire,63 Short-Form (SF)-36 general health questionnaire,67,68 North American Spine Society (NASS)69 treatment expectations, isometric push and pull, dynamic floor-to-waist lift, and isometric above-shoulder lifting tasks. In addition, a needle electromyography of the L2–L5 bands of the multifidus muscle was performed before and at 8 weeks after the radiofrequency denervation. Patients were evaluated with at least a 12 month follow-up. Statistical analysis was performed using median scores and interquartile ranges of all outcome measures, Friedman two-way analysis of variance, Wilcoxon paired test, and Spearman correlation coefficients. Sixty percent of patients experienced at least a 90% pain reduction, whereas 87% of patients experienced at least a 60% reduction in pain. This effect lasted for 12 months. Forty-seven percent of patients obtained absolute reduction of at least 5 in the VAS,64 and 60% obtained relative reduction of at least 3. They noted that, even for patients who experienced pain for more than 5 years, radiofrequency denervation of the medial branch was helpful, cost effective, and less time consuming than other interventions such as exercise-based physical therapy or manipulative care. The results of needle electromyography warrants a special mention, with 11 of 15 patients sustaining 100% denervation, whereas 4 achieved partial denervation.

A critical review of each of these studies is of prime importance if one is to derive a deep understanding of this therapeutic intervention for the treatment of lumbar zygapophyseal joint mediated pain. Each study used a small sample size, with van Kleef et al.60 and Dreyfuss et al.55 using only 15 subjects each in the treatment group. Gallagher et al.62 and Leclaire et al.61 did not specify how a successful outcome to the diagnostic injections was objectively rated. Dreyfuss et al.55 and Leclaire et al.61 were the only two sets of authors who followed their patients for at least 12 months. There were also discrepancies noted in reporting the diagnostic injection. Gallagher et al.,62 in their abstract, mention that the solution used was a combination of local anesthetic agent with steroid, whereas the main text of the paper states that the solution used was only local anesthetic. Van Kleef et al.60 used a double-blind, placebo-controlled injection paradigm. Unfortunately, patients were selected on the basis of a single positive diagnostic injection which, as discussed previously, is known to have a false-positive rate of approximately 38%.51 The technique used by van Kleef et al.61 was different, such that the electrodes were placed at an angle to the target nerve. Laboratory studies have shown that the electrode must lie parallel to the nerve if the nerve is to be optimally and maximally coagulated.56 This may explain why van Kleef et al.60 obtained only modest results. Similarly, van Kleef et al.60 and Dreyfuss et al.55 included subjects with low initial VAS scores. Although Dreyfuss et al.55 used the strictest inclusion criteria in their prospective audit, they unfortunately treated only a small sample size. By performing two different diagnostic injections with two anesthetic agents, each with a different duration of action, they tried to eliminate the false-positive responders. Also, during the radiofrequency denervation, the electrodes were placed meticulously to optimize coagulation of the nerve. As previously stated, these authors conducted a needle electromyography of L2–L5 bands of multifidus before and at 8 weeks after the denervation. Although electromyographic evidence of denervation indicates that the radiofrequency ablation successfully coagulated the assessed medial branch, such an outcome did not correlate with symptom improvement. However, this study did not include a control group. In the Leclaire et al.61 study, the inclusion criteria was significant relief of low back pain for more than 24 hours after the facet injection. Roland-Morris score65 was used as an important outcome measure, which is a measurement of functional limitation and not of pain relief. A more in-depth questionnaire on pain, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire,63 possibly could better identify the therapeutic response in these patients.

These conflicting trials, discussing the use of radiofrequency denervation in the management of lumbar zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain, highlight the use of varied inclusion criteria, varied treatment, lack of uniform outcome measures, use of concurrent interventions, and lack of a sufficient follow-up. A detailed review of these deficiencies and critical analysis of the relevant peer-reviewed publications can be found elsewhere.70,71 A more recent anatomical study undertaken by Lau et al.72 validates the prime importance of placement of electrodes parallel to the target nerve. This underscores the fact that a meticulous technique will lead to superior results.

The Agency for Health Care and Policy Research describes evidence rating for management of low back pain in adults.73 For the development of these guidelines, a rating schema was used to assess the strength or efficacy of a treatment or procedure. They offered five levels of strength: level I (conclusive): research-based evidence with multiple relevant and high-quality scientific studies; level II (strong): research-based evidence from at least one properly designed randomized, controlled trial of appropriate size (with at least 60 patients in each arm) and high-quality or multiple adequate scientific studies; level III (moderate): evidence from well-designed trials without randomization, single group pre-post cohort, time series, or matched case-controlled studies; level IV (limited): evidence from well-designed nonexperimental studies from more than one center or research group; and level V (intermediate): opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical evidence, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees. Critical review of the literature reveals that the type and strength of efficacy evidence for radiofrequency neurotomy in managing lumbar zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain is level III evidence.

CONCLUSION

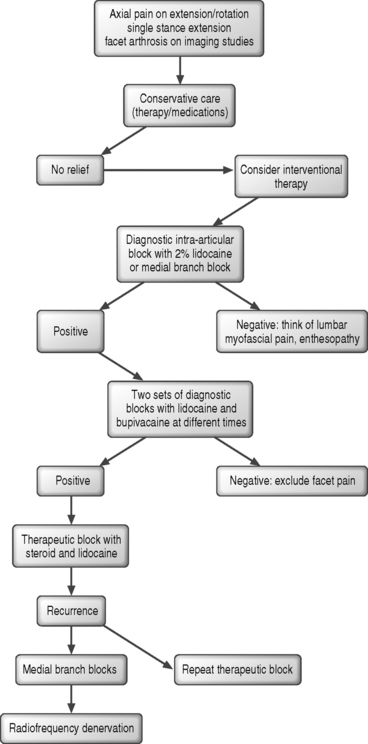

In summary, the process of establishing a diagnosis of lumbar zygapophyseal joint-mediated pain, the techniques used to make this diagnosis and implementing an effective treatment algorithm has evolved extensively over the past three decades since Mooney and Robertson proposed the posterior joints of the lumbar spine as a potential source of low back pain (Fig. 93.1). The question is not whether the syndrome of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain exists but how to come to an accurate diagnosis and how to treat it effectively. The challenge lies in the accurate diagnosis of this entity so that appropriate interventional therapy may be instituted. Regardless of the approach used, the diagnosis can only be affirmed using, at a minimum, a double-block paradigm due to the low positive predictive value of a single diagnostic injection. If attractive, compelling results are to be achieved following a lumbar radiofrequency denervation, the clinician needs to follow two basic but often overlooked steps: establish an accurate diagnosis of lumbar facet syndrome and then, during treatment, adhere to a meticulous placement of electrodes.

1 Anderson GBJ, Svensson HO. The intensity of work recovery in low back pain. Spine. 1983;8:880-887.

2 Spitzer WO, Leblanc FE, Dupuis M, editors. Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders: A monogram for clinicians. Spine. 1987;S12:1-59.

3 Manchikanti L, Singh V, Kloth D, et al. Interventional techniques in the management of chronic pain: Part 2.0. Pain Phys. 2001;4:24-96.

4 Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

5 Cassidy D, Carroll L, Cote P. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey. Spine. 1998.

6 Carey TS, Garrett JM, Jackman A, et al. Recurrence and care seeking after acute low back pain. Results of a long-term follow-up study. Med Care. 1999;37:157-164.

7 Van Den Hoogen HJM, Koes BW, Deville W, et al. The prognosis of low back pain in general practice. Spine. 1997;22:1515-1521.

8 Kuslich SD, Ulstrom CL, Michael CJ. The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: A report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operation on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22:181-187.

9 Goldthwait JE. The lumbosacral articulation: An explanation of many cases of lumbago, sciatica, and paraplegia. Boston Med and Surg J. 1911;164:365-372.

10 Ghormley RK. Low back pain. With special reference to the articular facets, with presentation of an operative procedure. JAMA. 1933;101:1773-1777.

11 Badgley CE. The articular facets in relation to low back pain and sciatic radiation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941;23:481.

12 Hirsch D, Inglemark B, Miller M. The anatomical basis for low back pain. Acta Orthop Scand. 1963;33:1.

13 Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:149-156.

14 McCall IW, Park WM, O’Brien JP. Induced pain referral from posterior elements in normal subjects. Spine. 1979;4:441-446.

15 Marks R. Distribution of pain provoked from lumbar facet joints and related structures during diagnostic spinal infiltration. Pain. 1989;39:37-40.

16 Fukui S, Ohseto K, Shiotani M, et al. Distribution of referral pain from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints and dorsal rami. Clin J Pain. 1997;12:303-307.

17 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints: Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine. 1994;19:1132-1137.

18 Schwarzer AC, Wang S, Bogduk N, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain. Ann Rhem Dis. 1995;54:100-106.

19 Bogduk N, Engel R. The menisci of the lumbar zygapophyseal joints. A review of their anatomy and clinical significance. Spine. 1984;9:454-460.

20 Bogduk N, Twomey LT. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine, 2nd edn. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1991.

21 Pedersen HE, Blunck CFJ, Gardner E. The anatomy of lumbosacral posterior rami and meningeal branches of spinal nerves (sinu-vertebral nerves). J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1956;38A:377-391.

22 Bogduk N, Wilson AS, Tynan W. The human lumbar dorsal rami. J Anat. 1982;134:383-397.

23 Bogduk N. The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1983;8(3):286-293.

24 Jackson HC, Winkelmann RK, Bickel WH. Nerve endings in the human spinal column and related structures. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1966;48A:1272.

25 Bogduk N. Nerves of the lumbar spine. In Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum, 3rd edn., New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:127-143.

26 Suseki K, Takahashi Y, Takahashi K, et al. Innervation of the lumbar facet joints. Spine. 1997;22:477-485.

27 El-Bohy AA, Goldberg SJ, King AI. Measurement of facet capsular stretch. Biomechanics symposium, Annual conference of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Cincinnati, OH. AMD. 1987;84:161.

28 Edgar MA, Ghadially JA. Innervation of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1976;115:35-41.

29 Brink EE, Pfaff DW. Vertebral muscles of back and tail of albino rat (Rattus norvegicus albinus). Brain Behab Evol. 1980;17:1-47.

30 Cavanaugh JM, El-Bohy A, Hardy WN, et al. Sensory innervation of soft tissues of the lumbar spine in the rats. J Orthop Res. 1989;7:378-388.

31 Ashton KI, Ashton BA, Gibson SJ, et al. Morphological basis for low back pain. Demonstration of fibers and neuropeptides in the lumbar facet joint capsule but not in ligamentum flavum. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:72.

32 Igarashi A, Kikuchi S, Konno S, et al. Inflammatory cytokines released from the facet joint tissue in degenerative lumbar spinal disorders. Spine. 2004;29:2091-2095.

33 Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Wedge JH, Yong-Hing K, et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylolysis and stenosis. Spine. 1978;3:319-327.

34 Fujiwara A, Tamai K, Yamato M, et al. The relationship between the facet joint osteoarthritis and disc degeneration of the lumbar spine: An MRI study. Eur J Spine. 1999;8:396-401.

35 Fujiwara A, Tamai K, An HS. The relationship between disc degeneration, facet joint osteoarthritism, and stability of the degenerative lumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:444-450.

36 Wiesel SW, Tsourmas N, Feffer HL. A study of computer assisted tomography I: The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine. 1981;9:549-551.

37 Jensen M, Brant-Zwawadzki M, Obuchowski N. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;2:69-73.

38 Schwarzer AC, Wang S, O’Driscoll D, et al. The ability of computed tomography to identify a painful zygapophyseal joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:907-912.

39 Ryan PJ, Di Vadi L, Gibson T, et al. Facet joint injection with low back pain and increased facetal activity on bone scintigraphy with SPECT: A pilot study. Nucl Med Commun. 1992;13:401.

40 Schwarzer AC, Scott AM, Wang S, et al. The role of bone scintigraphy in chronic low back pain: Comparison of SPECT and planar images and zygapophyseal joint injection. Aust NZ J Med. 1992;22:185.

41 Bogduk N. International Spinal Injection Society guidelines for the performance of spinal injection procedures: Part 1: Zygapophyseal joint blocks. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:292-297.

42 Dreyfuss PH, Dryer SJ, Herring SA. Contemporary concepts in spine care: Lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joint injections. Spine. 1995;20(18):2040-2047.

43 Kaplan M, Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, et al. The ability of lumbar medial branch blocks to anesthetize the zygapophyseal joint: A physiologic challenge. Spine. 1998;23(17):1847-1852.

44 Carette S, Marcoux S, Truchon R, et al. A controlled trial of corticosteroid injections in the facet joints for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1002-1007.

45 Carrera GF. Lumbar facet joint injection in low back pain and sciatica: Preliminary results. Radiology. 1980;137:665-667.

46 Carrera GF, Williams AL. Current concepts in evaluation of the lumbar facet joints. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1984;21:85-104.

47 Destouet JM, Gilula LA, Murphy WA, et al. Lumbar facet joint injection: Indication, technique, clinical correlation, and preliminary results. Radiology. 1982;145:321-325.

48 Destouet JM, Murphy WA. Lumbar facet block: indication and technique. Orthop Rev. 1985;14:57-65.

49 Helbig T, Lee CK. The lumbar facet syndrome. Spine. 1988;13:61-64.

50 Raymond J, Dumas JM. Intra-articular facet block: diagnostic test or therapeutic procedure? Radiology. 1989;151:333-336.

51 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby, et al. The false-positive rate of uncontrolled diagnostic blocks of the lumbar zygapophyseal joints. Pain. 1994;58:195-200.

52 Bonica JJ. Local anesthesia and regional blcoks. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1989:724-743.

53 Bonica JJ, Buckley FP. Regional analgesia with local anesthetics. In: Bonica JJ, editor. The management of pain. Philadelphia: Lea & Fibeger; 1990:1883-1966.

54 Boas RA. Nerve blocks in the diagnosis of low back pain. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:806-816.

55 Dreyfuss P, Halbrrok B, Pauza K, et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain. Spine. 2000;25(10):1270-1277.

56 Bogduk N, Macintosh J, Marshland A. Technical limitations to the efficacy of radiofrequency neurotomy for spinal pain. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:529-535.

57 Rees WES. Multiple bilateral subcutaneous rhizolysis of segmental nerves in the treatment of the intervertebral disc syndrome. Ann Gen Pract. 1971;16:126-127.

58 Shealy CN. The role of spinal facets in back and sciatic pain. Headache. 1974;14:101.

59 Shealy CN. Facet denervation in the management of back and sciatic pain. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:157-164.

60 Van Kleef M, Barendse GAM, Kessels A, et al. Randomized trial of radiofrequency lumbar facet denervation for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1999;24(18):1937-1942.

61 Leclaire R, Fortin L, Lambert T, et al. Radiofrequency facet joint denervation in the treatment of low back pain: a placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess efficacy. Spine. 2001;26(13):1411-1417.

62 Gallagher J, Petriccione di Vadi PL, Wedley JR, et al. Radiofrequency facet joint denervation in the treatment of low back pain: a prospective controlled double-blind study to assess its efficacy. Pain Clin. 1994;7(3):193-198.

63 Melzack R. The McGill pain questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277-299.

64 Huskisson EC. Visual analog scales. In: Melzack R, editor. Pain measurement and assessment. New York: Raven Press; 1983:33-37.

65 Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8:141-144.

66 Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, et al. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66(8):271-273.

67 McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247-263.

68 Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483.

69 Daltroy LH, Cats-Beril WL, Katz JN, et al. The North American Spine Society lumbar spine outcome assessment instrument: reliability and validity tests. Spine. 1996;21:741-749.

70 Niemisto L, Kalso E, Malmivaara A, et al. Radiofrequency denervation for neck and back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine. 2003;28:1877-1888.

71 Slipman CW, Bhat AL, Gilchrist RV, et al. A critical review of the evidence for the use of zygapophyseal injections and radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of low back pain. Spine J. 2003;3:310-316.

72 Lau P, Mercer S, Govind J, et al. The surgical anatomy of lumbar medial branch neurotomy (facet denervation). Pain Med. 2004;5:289-298.

73 Bigos SJ, Boyer OR, Braen GR, et al. Clinical practice guideline number 4: Acute low back problems in adults. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, December 1994. AHCPR Publication 95-0642