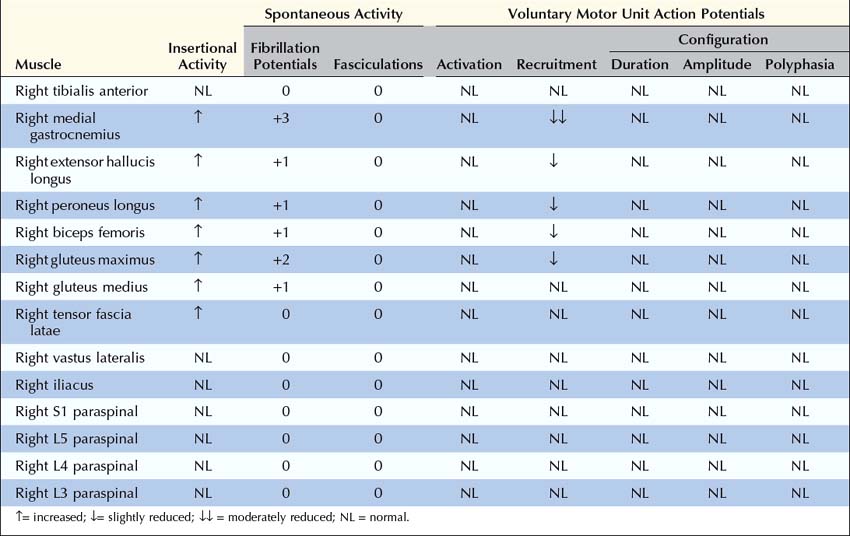

29 Radiculopathy

Clinical

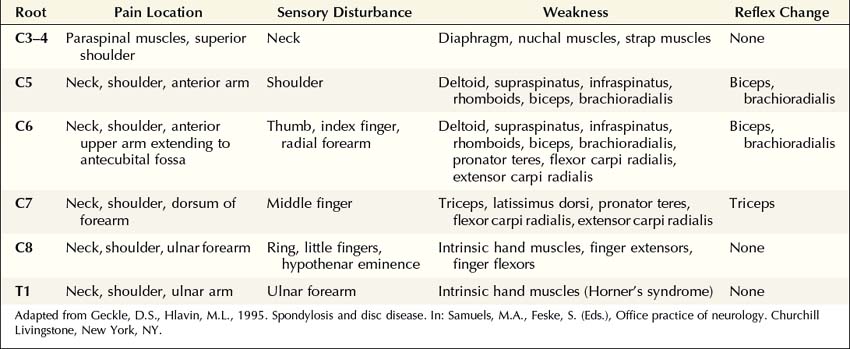

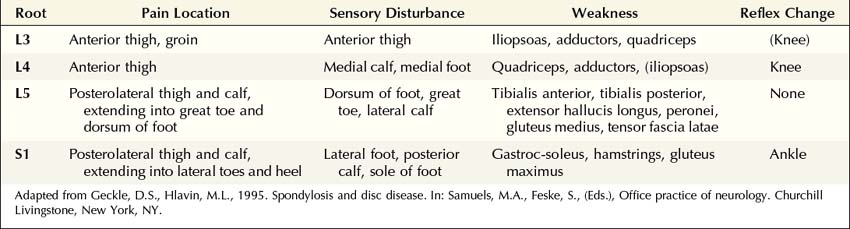

The clinical hallmark of radiculopathy includes pain and paresthesias radiating in the distribution of a nerve root, often associated with sensory loss and paraspinal muscle spasm. Motor dysfunction may also be present. Radiculopathy caused by degenerative bone and disc disease most often affects the cervical (C3–C8) and lower lumbosacral (L3–S1) segments, resulting in well-recognized clinical syndromes (Tables 29–1 and 29–2). Associated paraspinal muscle spasm commonly limits the range of motion, and movement of the neck or back may exacerbate symptoms.

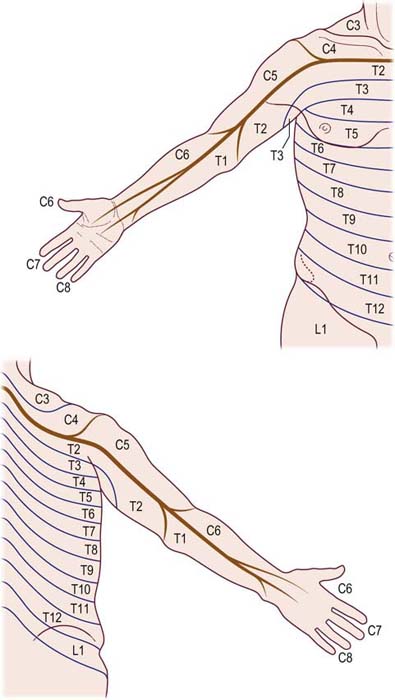

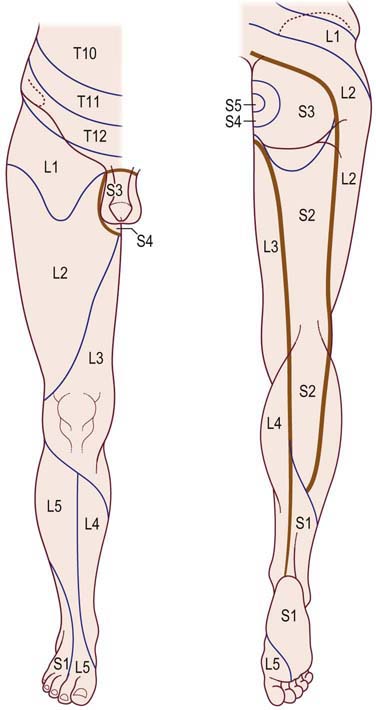

The particular sensory and motor symptoms associated with a radiculopathy depend on which nerve root or roots are involved. Each nerve root supplies cutaneous sensation to a specific area of skin, known as a dermatome (Figures 29–1 and 29–2), and motor innervation to certain muscles, known as a myotome (Tables 29–3 and 29–4). Each dermatome overlaps widely with adjacent dermatomes. Consequently, it is very unusual for a patient with an isolated radiculopathy to develop a severe or dense sensory disturbance. Dense numbness usually is more indicative of a peripheral nerve lesion than a radiculopathy. In a patient with radiculopathy, sensory loss more often is vague, poorly defined, or absent, despite the presence of paresthesias.

FIGURE 29–1 Cervical and thoracic dermatomes.

(From Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. London: Baillière Tindall. With permission, 1986.)

FIGURE 29–2 Lower thoracic and lumbosacral dermatomes.

(From Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. London: Baillière Tindall. With permission, 1986.)

Table 29–3 Root Innervation of Major Upper Extremity Muscles

| Root | Muscle | Nerve |

|---|---|---|

| C4 5 | Rhomboids | Dorsal scapular |

| C5 6 | Supraspinatus | Suprascapular |

| C5 6 | Infraspinatus | Suprascapular |

| C5 6 | Deltoid | Axillary |

| C5 6 | Biceps brachii | Musculocutaneous |

| C5 6 | Brachioradialis | Radial |

| C5 6 7 | Serratus anterior | Long thoracic |

| C5 6 7 | Pectoralis major: Clavicular | Lateral pectoral |

| C6 7 8 T1 | Pectoralis major: Sternal | Medial pectoral |

| C6 7 | Flexor carpi radialis | Median |

| C6 7 | Pronator teres | Median |

| C6 7 | Extensor carpi radialis longus | Radial |

| C6 7 8 | Latissimus dorsi | Thoracodorsal |

| C6 7 8 | Triceps brachii | Radial |

| C6 7 8 | Anconeus | Radial |

| C7 8 | Extensor digitorum communis | Radial |

| C7 8 | Flexor digitorum sublimis | Median |

| C7 8 | Extensor indicis proprius | Radial |

| C7 8 | Extensor carpi ulnaris | Radial |

| C7 8 T1 | Flexor pollicis longus | Median |

| C7 8 T1 | Flexor digitorum profundus | Median/Ulnar |

| C8 T1 | Flexor carpi ulnaris* | Ulnar |

| C8 T1 | First dorsal interosseus | Ulnar |

| C8 T1 | Abductor digiti minimi | Ulnar |

| C8 T1 | Abductor pollicis brevis | Median |

Note: Underlining indicates predominant root innervation.

* In some individuals, the flexor carpi ulnaris may have a C7 contribution.

Table 29–4 Root Innervation of Major Lower Extremity Muscles

| Root | Muscle | Nerve |

|---|---|---|

| L2 3 4 | Iliacus | Femoral |

| L2 3 4 | Rectus femoris | Femoral |

| L2 3 4 | Vastus lateralis and medialis | Femoral |

| L2 3 4 | Adductors | Obturator |

| L4 5 | Tibialis anterior | Deep peroneal |

| L4 5 | Extensor digitorum longus | Deep peroneal |

| L4 5 S1 | Extensor hallucis longus | Deep peroneal |

| L4 5 S1 | Extensor digitorum brevis | Deep peroneal |

| L4 5 S1 | Medial hamstrings | Sciatic |

| L4 5 S1 | Gluteus medius | Superior gluteal |

| L4 5 S1 | Tensor fascia latae | Superior gluteal |

| L5 S1 | Tibialis posterior | Tibial |

| L5 S1 | Flexor digitorum longus | Tibial |

| L5 S1 | Peronei | Superficial peroneal |

| L5 S1 | Lateral hamstrings (biceps femoris) | Sciatic |

| L5 S1 2 | Gastrocnemius – lateral | Tibial |

| L5 S1 2 | Gluteus maximus | Inferior gluteal |

| L5 S1 2 | Abductor hallucis brevis | Tibial–medial plantar |

| S1 2 | Abductor digiti quinti pedis | Tibial–lateral plantar |

| S1 2 | Gastrocnemius – medial | Tibial |

| S1 2 | Soleus | Tibial |

Note: Underlining indicates predominant root innervation.

Electrophysiologic Evaluation

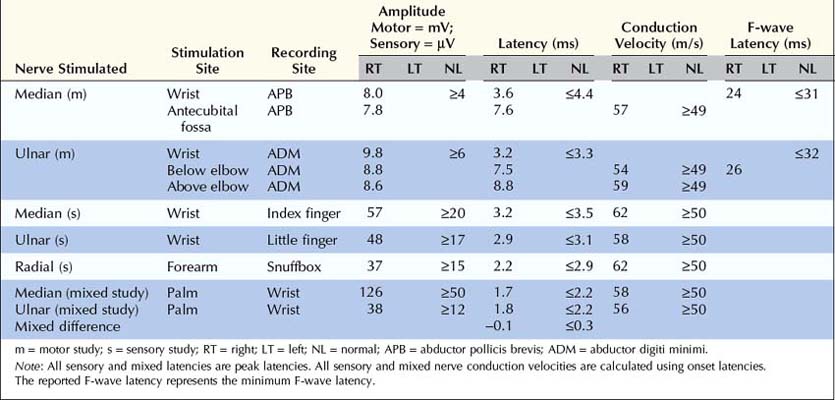

Nerve Conduction Studies

In patients with radiculopathy, nerve conduction studies typically are normal, and the electrodiagnosis is established with needle EMG (Box 29–1). Although some motor abnormalities are occasionally seen in radiculopathy, the more important reason to perform nerve conduction studies is to exclude other conditions that may mimic radiculopathy, especially entrapment neuropathy and plexopathy. In cases of upper extremity lesions, ulnar neuropathy at the elbow and CTS must be excluded. Ulnar neuropathy and C8 radiculopathy both can present with pain in the arm associated with numbness of the little and ring fingers. Likewise, pain in the arm with paresthesias involving the thumb, index, and middle fingers may be seen in C6–C7 radiculopathy and CTS. In the case of lower extremity symptoms, one must exclude peroneal neuropathy at the fibular neck. Both peroneal palsy and L5 radiculopathy may present with pain in the leg, accompanied by footdrop and paresthesias over the dorsum of the foot and lateral calf. In more severe cases, the clinical differentiation between a radiculopathy and a common entrapment usually is straightforward. In mild or early cases, however, the distinction often is more difficult, and nerve conduction studies are useful to either demonstrate or exclude an entrapment neuropathy.

Box 29–1

Recommended Nerve Conduction Study Protocol for Radiculopathy

Upper Extremity

• Perform median and ulnar motor conduction studies, recording abductor pollicis brevis and abductor digiti minimi, respectively. Be sure to exclude carpal tunnel syndrome in suspected C6–C7 radiculopathy and ulnar neuropathy at the elbow in suspected C8 radiculopathy. Ideally, studies should be performed bilaterally if CMAP distal latency, amplitude, or conduction velocity is abnormal or borderline.

• Perform at least one sensory study, ideally in the distribution of the suspected radiculopathy (see Table 29–6). It is best to perform the sensory studies bilaterally if the amplitude on the symptomatic side is low or borderline.

• In suspected C6–C7 radiculopathy (paresthesias into thumb, index, and middle fingers), perform at least one median versus ulnar internal comparison study (e.g., median versus ulnar palm-to-wrist mixed studies), as a sensitive internal control, to definitely exclude electrophysiologic evidence of median neuropathy across the wrist.

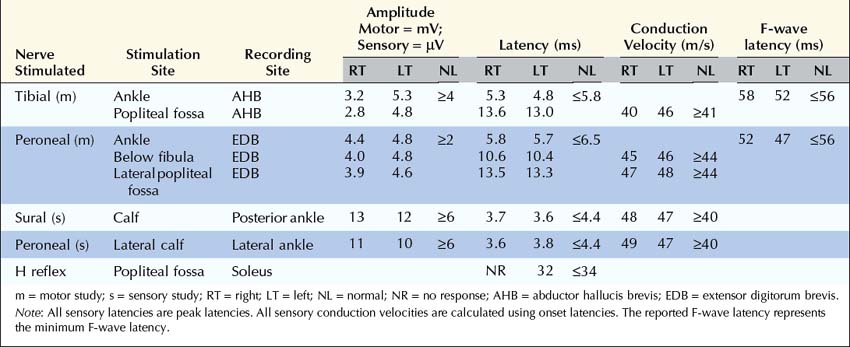

Lower extremity

• Perform peroneal and tibial motor conduction studies, recording extensor digitorum brevis and abductor hallucis brevis, respectively. Be sure to exclude peroneal palsy at the fibular neck, especially in suspected L5 radiculopathy. Ideally, studies should be performed bilaterally if CMAP distal latency, amplitude or conduction velocity is abnormal or borderline.

• Perform at least one sensory study, ideally in the distribution of the suspected radiculopathy (see Table 29–6). It is best to perform these studies bilaterally if the amplitude on the symptomatic side is low or borderline.

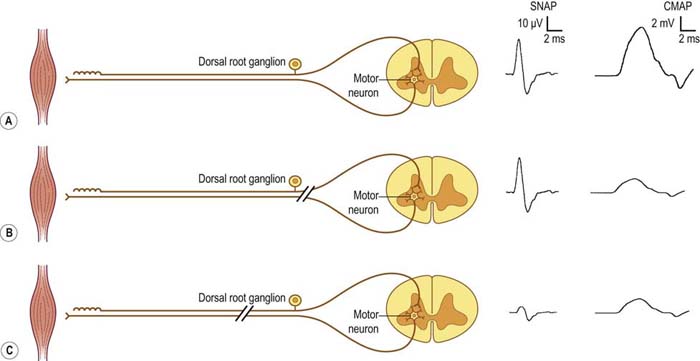

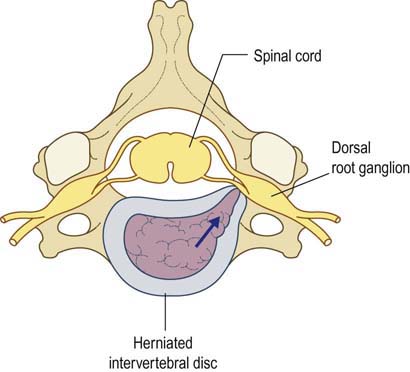

Sensory studies are the most important part of the nerve conduction studies in the assessment of radiculopathy. The sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) remains normal in lesions proximal to the dorsal root ganglion (Figure 29–3). Nearly all radiculopathies, including those caused by compression from herniated discs and spondylosis, damage the root proximal to the dorsal root ganglion (Figure 29–4). Conversely, lesions at or distal to the dorsal root ganglion result in decreased SNAP amplitudes if they are associated with axonal loss. Thus, lesions of the plexus and peripheral nerve (proximal and distal nerve) are associated with abnormal SNAPs, whereas lesions of the nerve root result in normal SNAPs.

FIGURE 29–3 Sensory and motor potentials in axonal loss lesions distal and proximal to the dorsal root ganglion.

FIGURE 29–4 Radiculopathy and sparing of the dorsal root ganglion.

(From Wilbourn, A.J., 1993 Radiculopathies. In: Brown, W.F., Bolton, C.F. (Eds.), Clinical electromyography, 2nd ed. Butterworth, Boston. With permission.)

It is always imperative to check the SNAP that is in the distribution of the sensory symptoms (Table 29–5). For instance, if a patient has pain down the arm with tingling and paresthesias of the middle finger, the median sensory response to the middle finger should be checked. In such a case, if the lesion is at or distal to the dorsal root ganglion (e.g., in the brachial plexus or median nerve) and there is axonal loss, the SNAP amplitude will be abnormal, if enough time has passed that wallerian degeneration has taken place. On the other hand, if the lesion is proximal to the dorsal root ganglion (e.g., C7 radiculopathy), the SNAP amplitude will be normal. The presence of a normal SNAP yields important diagnostic information. A normal SNAP in the same distribution as sensory symptoms and signs should always suggest a lesion proximal to the dorsal root ganglion (although a proximal demyelinating or acute peripheral nerve lesion also can result in a normal SNAP). One important rare exception to his rule is discussed below.

| SNAP | Root |

|---|---|

| Lateral antebrachial cutaneous | C5–C6 |

| Radial to the thumb | C6 |

| Median to the thumb | C6 |

| Radial to the snuffbox | C6–C7 |

| Median to the index finger | C6–C7 |

| Median to the middle finger | C7 |

| Median to the ring finger | C7–C8 |

| Ulnar to the ring finger | C7–C8 |

| Ulnar to the little finger | C8 |

| Dorsal ulnar cutaneous | C8 |

| Medial antebrachial cutaneous | T1 |

| Saphenous | L4 |

| Superficial peroneal sensory | L5 |

| Sural | S1 |

SNAP, sensory nerve action potential.

Note: SNAPs are normal in lesions proximal to the dorsal root ganglion, including lesions resulting in radiculopathies. When evaluating a possible radiculopathy, one should examine at least one SNAP in the distribution of the suspected radiculopathy. For example, the ulnar SNAP to the little finger should be normal in a C8 radiculopathy. If it is abnormal, the lesion likely is not at the root, unless there is another reason for the SNAP to be abnormal, such as a superimposed ulnar neuropathy at the elbow.

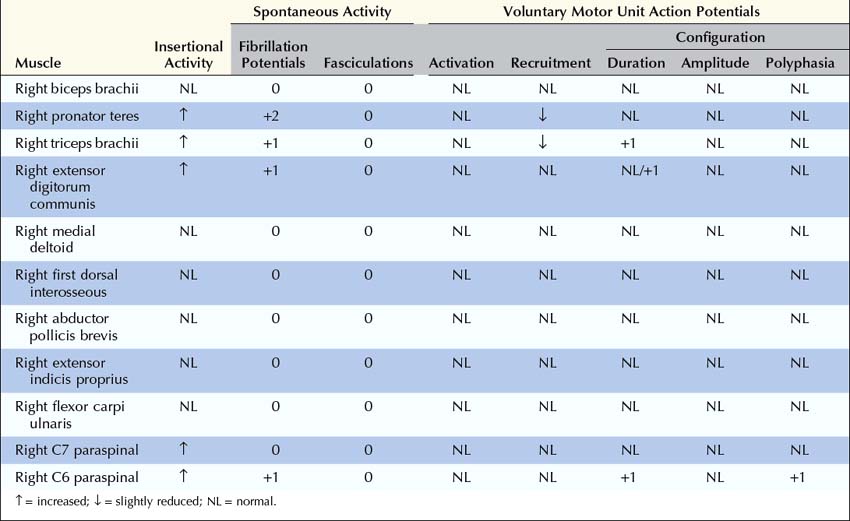

Electromyographic Approach

The needle EMG strategy in radiculopathy is straightforward. Distal, proximal, and paraspinal muscles in the symptomatic extremity are sampled, looking for abnormalities in a myotomal pattern that are beyond the distribution of any one nerve (Box 29–2). It is important to exclude a mononeuropathy, polyneuropathy, or more diffuse process that might account for the signs and symptoms.

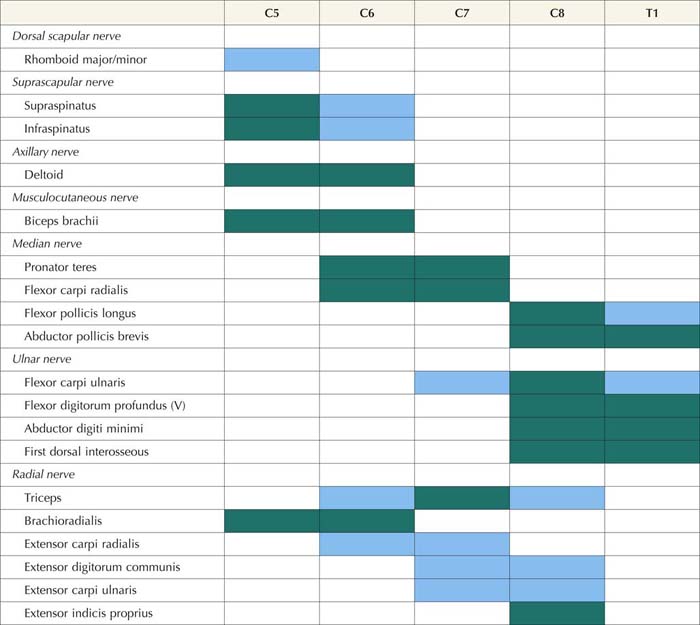

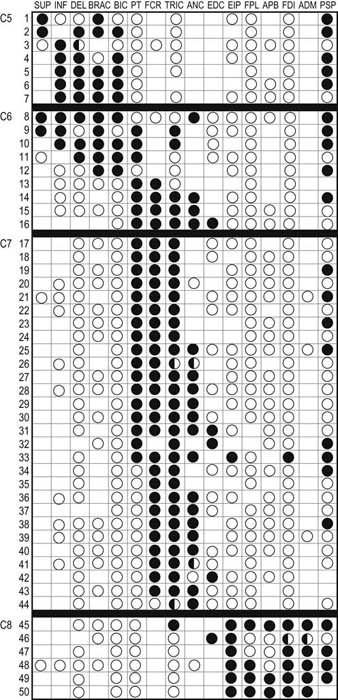

1. Muscles innervated by the same myotome but by different nerves must be sampled to exclude a mononeuropathy. For example, the finding of fibrillation potentials and decreased recruitment of motor unit action potentials (MUAPs) in the triceps brachii (C6–C7–C8), extensor carpi radialis (C6–C7), and extensor carpi ulnaris (C7–C8) could indicate an acute, predominantly C7 radiculopathy, since they all share this nerve root. However, because each of these muscles is also innervated by the radial nerve, one could not differentiate between a radial neuropathy and a C7 radiculopathy by sampling only these muscles. If, however, the flexor carpi radialis (C6–C7) or pronator teres (C6–C7) were also sampled and showed fibrillation potentials with reduced recruitment of MUAPs, the pattern of abnormalities could no longer be explained by a single nerve lesion (radial neuropathy) because the last two muscles are both innervated by the median nerve. Since all of these muscles have C7 innervation in common, despite different peripheral nerve innervation, this pattern of abnormalities points toward a radiculopathy as the lesion. Note that while nearly all muscles are innervated by multiple myotomes, certain muscles are predominantly innervated by one myotome, and these muscles are the most useful in the electrodiagnosis of radiculopathy (Tables 29–6 and 29–7).

2. Proximal and distal muscles that are innervated by the same myotome should be sampled to exclude a distal-to-proximal pattern of abnormalities such as occurs in polyneuropathy. For example, the finding of fibrillation potentials with reduced recruitment of MUAPs in the extensor hallucis longus (L5–S1), medial gastrocnemius (S1–S2), and peroneus longus (L5–S1) muscles would be consistent with an L5–S1 radiculopathy. However, because these are all distal muscles, one could not exclude a typical distal polyneuropathy, especially if the sural sensory potential is borderline low. On the other hand, if more proximal S1 muscles, such as the gluteus maximus (L5–S1–S2), also show similar abnormalities, a distal-to-proximal gradient would be excluded, making radiculopathy the more likely diagnosis.

3. Muscles innervated by myotomes above and below the suspected lesion level must be sampled to exclude a more widespread or diffuse process. For example, if a C7 radiculopathy is suspected, muscles predominantly innervated by the C5–C6 and C8–T1 nerve roots also should be sampled.

4. The paraspinal muscles should always be examined. Examination of the paraspinal muscles is crucial in the evaluation of radiculopathy. The paraspinal muscles are innervated by the dorsal rami, which arise directly from the spinal nerves. Neuropathic abnormalities in these muscles nearly always imply a lesion at or proximal to the nerve roots. Other than the presence of normal sensory nerve conduction studies, abnormalities in the paraspinal muscles are the only other finding that can conclusively differentiate radiculopathy from plexopathy. Unfortunately, the paraspinal muscles are affected in only about 50% of cases of radiculopathy. Thus, the absence of paraspinal abnormalities cannot exclude a radiculopathy; however, the presence of paraspinal abnormalities clearly localizes the lesion to the root or anterior horn cell level. Note that if the patient has had previous neck or back surgery, the paraspinal muscles in the area of previous surgery may remain abnormal for years after the surgery, and any abnormal findings in these muscles would not help differentiate a new lesion from a remote effect of previous surgery. Thus, paraspinal muscles in the area of previous surgery are generally not sampled (see below).

Box 29–2

Recommended Electromyographic Protocol for Radiculopathy

1. Examine the relevant myotome first. If possible, sample at least two muscles in each of the following areas: paraspinal, proximal and distal limb. In each limb area, try to use muscles with similar root innervation but different peripheral nerve innervation.

2. If abnormalities are found, examine muscles in adjacent myotomes, above and below the suspected lesion level, to exclude a more widespread or diffuse lesion.

3. If findings are mild or equivocal, compare with a contralateral asymptomatic muscle.

4. In the post-spinal surgery setting, fibrillation potentials in the paraspinal muscles do not necessarily have diagnostic significance; thus, they are not helpful to sample.

Table 29–6 Electromyography in Upper Extremity Radiculopathy: Most Useful Muscles to Sample

Note: Green squares indicate “marker” muscles that are most often abnormal for that root in an isolated radiculopathy. Blue squares indicate muscles that may be involved, but are abnormal less frequently. This chart shows those muscles that are most helpful in making the electrodiagnosis of radiculopathy but does not indicate the entire myotomal representation of the individual muscle (see Table 29–3).

From Wilbourn, A.J., 1993. Radiculopathies. In: Brown, W.F., Bolton, C.F. (Eds.), Clinical electromyography, 2nd ed. Butterworth, Boston, with permission.

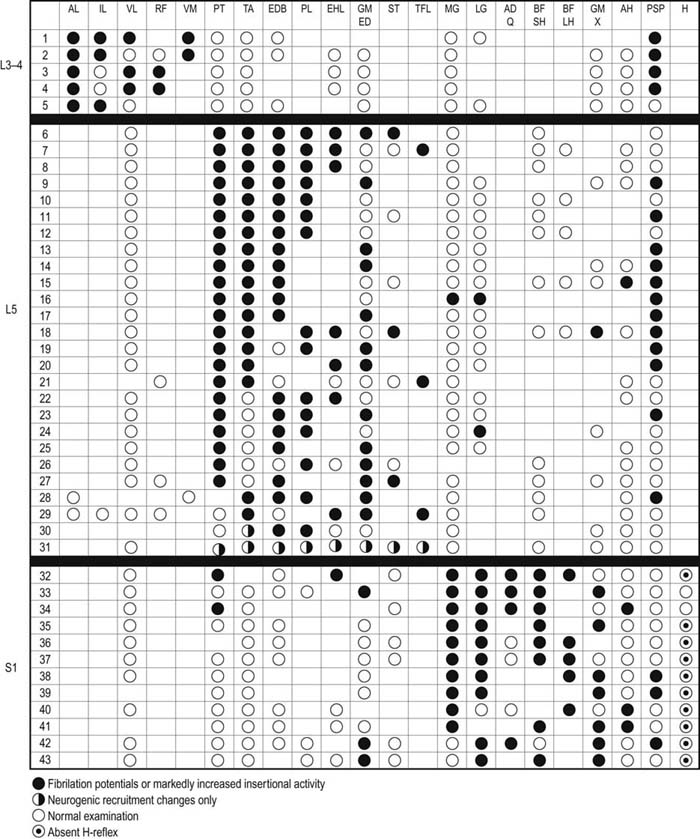

Table 29–7 Electromyography in Lower Extremity Radiculopathy: Most Useful Muscles to Sample

Note: Green squares indicate “marker” muscles that are most often abnormal for that root in an isolated radiculopathy. Blue squares indicate muscles that may be involved, but are abnormal less frequently. This chart shows those muscles that are most helpful in making the electrodiagnosis of radiculopathy but does not indicate the entire myotomal representation of the individual muscle (see Table 29–4).

From Wilbourn, A.J., 1993. Radiculopathies. In: Brown, W.F., Bolton, C.F. (Eds.), Clinical electromyography, 2nd ed. Butterworth, Boston, with permission.

Limitations of the Needle Electromyographic Study in Radiculopathy

It may be Difficult to Localize a Radiculopathy to a Single Root Level

In studies of patients who had a surgically defined single-level radiculopathy, the correct level often could be deduced from extensive needle EMG studies (Figures 29–5 and 29–6). However, not infrequently there was significant overlap between adjacent segments, making a single root localization difficult. The most difficult levels to differentiate were C6 from C7.

The Paraspinal Muscles may be Normal

One expects the paraspinal muscles to be abnormal in radiculopathy, and they often are (Figures 29–5 and 29–6). In some cases, however, they are normal. This may be due to fascicular sparing of fibers to the dorsal rami or may simply be due to sampling error. In addition, some patients have difficulty tolerating the paraspinal examination and consequently may not be able to relax those muscles. The paraspinal needle examination is best done with the patient lying on his or her side in the fetal position, with the side to be studied facing up. This position often will relax the paraspinal muscles. If relaxation is incomplete, however, it may be difficult or impossible to exclude denervation. This situation is encountered most often when studying the thoracic paraspinal muscles.

Abnormal Paraspinal Muscles are Useful in Identifying a Radiculopathy but Not the Segmental Level of the Lesion

• The spinous process is first identified and marked.

• The needle insertion point is located 2.5 cm lateral and 1.0 cm rostral to the spinous process (Figure 29–7).

• The needle is directed medially at a 45 degree angle and inserted no more than 3.5 cm.

• When bone is reached, the needle is slightly withdrawn.

• If no bone is encountered, the needle is pulled back and redirected at 60 degrees but no deeper than 5 cm.

There is no Difference between a Radiculopathy/Polyradiculopathy and Focal/Diffuse Motor Neuron Disease on the Electromyographic Study

In the Elderly, it may not be Possible to Differentiate a Mild Chronic Distal Polyneuropathy from Mild Chronic Bilateral L5–S1 Radiculopathies

• Sural and superficial peroneal SNAPs are just at the lower limits of normal in amplitude

• Peroneal and tibial CMAP amplitudes are slightly reduced, with mildly slowed conduction velocities although still in the range of axonal loss

• Peroneal and tibial F responses and H reflexes are slightly prolonged

• Denervation/reinnervation changes are present in the distal leg muscles

• Nerve conduction study and EMG findings are normal in the upper extremities

![]() Example Cases

Example Cases

Case 29–1

Case 29–1

Case 29–2

Case 29–2

Summary

At this point, we are ready to formulate our electrophysiologic impression.

1986 Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. London: Baillière Tindall, 1986.

Geckle D.S., Hlavin M.L. Spondylosis and disc disease. In: Samuels M.A., Feske S. Office practice of neurology. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

Levin K.H. L5 radiculopathy with reduced superficial peroneal sensory responses: intraspinal and extraspinal causes. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:3–7.

Nardin R.A., Raynor E.M., Rutkove S.B. Fibrillations in lumbosacral paraspinal muscles of normal subjects. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:1347–1349.

Wilbourn A.J. Radiculopathies. Brown W.F., Bolton C.F. Clinical electromyography, 2nd ed, Boston: Butterworth, 1993.