Chapter 266 Rabies

Treatment and Prognosis

Rabies is generally fatal. There are 3 survivors from rabies infection through the use of the Milwaukee Protocol (www.mcw.edu/rabies). Deep sedation is induced to avoid dysautonomia while the immune response develops. Survival is estimated at 20%; neurologic outcome can be very good. Among 6 survivors of rabies after failure of vaccine prophylaxis, only 2 had a satisfactory neurologic outcome. Neither rabies immune globulin (RIG) nor rabies vaccine alters the course of disease once symptoms have appeared. Antiviral treatments have not been effective. Ribavirin, which delays the immune response, is to be avoided during early management. In contrast, appearance of the normal antibody response at 7-10 days is associated with clearance of salivary viral load. Nimodipine is recommended as prophylaxis against cerebrovascular spasm.

Prevention

Postexposure Prophylaxis

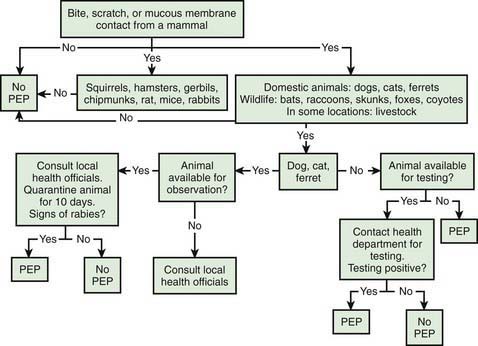

The relevance of rabies for most pediatricians centers on evaluating whether an animal exposure warrants PEP (Table 266-1). No case of rabies has been documented in a person receiving the fully recommended schedule of PEP since introduction of modern cellular vaccines in the 1970s.

| ANIMAL TYPE | EVALUATION AND DISPOSITION OF ANIMAL | POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Dogs, cats, and ferrets | Healthy and available for 10 days of observation | Prophylaxis only if animal shows signs of rabies* |

| Rabid or suspected of being rabid† | Immediate immunization and RIG | |

| Unknown (escaped) | Consult public health officials for advice | |

| Bats, skunks, raccoons, foxes, and most other carnivores; woodchucks | Regarded as rabid unless geographic area is known to be free of rabies or until animal proven negative by laboratory tests† | Immediate immunization and RIG |

| Livestock, rodents, and lagomorphs (rabbits, hares, and pikas) | Consider individually | Consult public health officials. Bites of squirrels, hamsters, guinea pigs, gerbils, chipmunks, rats, mice and other rodents, rabbits, hares, and pikas almost never require antirabies treatment. |

RIG, rabies immune globulin.

* During the 10-day observation period, at the first sign of rabies in the biting dog, cat, or ferret, treatment of the exposed person with RIG (human) and vaccine should be initiated. The animal should be euthanized immediately and tested.

† The animal should be euthanized and tested as soon as possible. Holding for observation is not recommended. Immunization is discontinued if immunofluorescent test result for the animal is negative.

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book 2009: report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Given the incubation period for rabies, PEP is a medical urgency, not emergency. Algorithms have been devised to aid practitioners in deciding when to initiate rabies PEP (Fig. 266-1). The decision to proceed ultimately depends on the local epidemiology of animal rabies as determined by active surveillance programs, information that can be obtained from local and state health departments. In general, bats, raccoons, skunks, coyotes, and foxes should be considered rabid unless proven otherwise through euthanasia and testing of brain tissue, whereas bites from small herbivorous animals (squirrels, hamsters, gerbils, chipmunks, rats, mice, and rabbits) can be discounted. The response to bites from a pet, particularly a dog, cat, or ferret, depends on local surveillance statistics and on whether the animal is available for observation.

The 1st step in rabies PEP is to cleanse the wound thoroughly. Soapy water is sufficient for an enveloped virus, and its effectiveness is supported by broad experience. Other commonly used disinfectants, such as iodine-containing preparations, are virucidal and should be used in addition to soap when available. Probably the most important aspect of this component is that the wound is cleansed with copious volumes of disinfectant and primary closure is avoided. Antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis (Chapter 203) should be applied with the use of usual wound care criteria.

The 3rd component of rabies PEP is immunization with inactivated vaccine. In the developed world, cell-based vaccines have replaced previous preparations. Two formulations currently are available in the USA, namely, RabAvert (Chiron Behring Vaccines, Maharashtra, India), a purified chick-embryo cell cultivated vaccine, and Imovax Rabies (Aventis Pasteur, Bridgewater, NJ), cultivated in human diploid cell cultures. In both children and adults, both vaccines are administered intramuscularly in a 1-mL volume in the deltoid or anterolateral thigh on days 0, 3, 7, and 14 after presentation. Injection into the gluteal area has been associated with a blunted antibody response, so this area should not be used. The rabies vaccines can be safely administered during pregnancy. In most persons the vaccine is well tolerated; most adverse effects are related to booster doses. Pain and erythema at the injection site occur commonly, and local adenopathy, headache, and myalgias occur in 10-20% of patients. Approximately 5% of patients who receive the human diploid cell vaccine experience an immune complex–mediated allergic reaction, including rash, edema, and arthralgias, several days after a booster dose. The World Health Organization (WHO) has approved schedules using smaller amounts of vaccine, administered intradermally, that are immunogenic and protective (www.who.int/rabies/human/postexp/en/), but none is approved for use in the USA. Other cell culture–derived rabies virus vaccines are available in the developing world. A few countries still produce nerve tissue–derived vaccines; these preparations are poorly immunogenic, and cross reactivity with human nervous tissue may occur with their use, producing severe neurologic symptoms even in the absence of rabies infection.

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

The killed rabies vaccine can be given to prevent rabies in persons at high risk for exposure to wild-type virus, including laboratory personnel working with rabies virus, veterinarians, and others likely to be exposed to rabid animals as part of their occupation. Pre-exposure prophylaxis should be considered for persons traveling to a rabies-endemic region where there is a credible risk for a bite or scratch from a rabies-infected animal, particularly if there is likely to be a shortage of RIG or cell culture–based vaccine (Chapter 168). Rabies vaccine as part of the routine vaccine series is under investigation in some countries. The schedule for pre-exposure prophylaxis consists of 3 intramuscular injections on days 0, 7, and 21 or 28. PEP in the patient who has received pre-exposure prophylaxis or a prior full schedule of PEP consists of 2 doses of vaccine (1 each on days 0 and 3) and does not require RIG. Immunity from pre-exposure prophylaxis wanes after several years and requires boosting if the potential for exposure to rabid animals recurs.

Bakker AB, Python C, Kissling CJ, et al. First administration to humans of a monoclonal antibody cocktail against rabies virus: safety, tolerability, and neutralizing activity. Vaccine. 2008;26:5922-5927.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health response to a rabid dog in an animal shelter—North Dakota and Minnesota, 2010. MMWR. 2011;59(51):1678-1680.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1-9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Presumptive abortive human rabies—Texas, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:185-190.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human vaccinia infection after contact with a raccoon rabies vaccine bait—Pennsylvania, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1204-1207.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human exposures to a rabid bat—Montana, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:557-560.

De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Mimault P, et al. Bats in the bedroom, bats in the belfry: reanalysis of the rationale for rabies postexposure prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1493-1499.

Hampson K, Dobson A, Kaare M, et al. Rabies exposures, post-exposure prophylaxis and deaths in a region of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e339.

Hu WT, Willoughby REJr, Dhonau H, et al. Long-term follow-up after treatment of rabies by induction of coma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:945-946.

Manning SE, Rupprecht CE, Fishbein D, et al. Human rabies prevention—United States, 2008: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-3):1-28.

Mattner F, Henke-Gendo C, Martens A, et al. Risk of rabies infection and adverse effects of postexposure prophylaxis in healthcare workers and other patient contacts exposed to a rabies virus-infected lung transplant recipient. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:513-518.

Pengsaa K, Limkittikul K, Sabchareon A, et al. A three-year clinical study on immunogenicity, safety, and booster response of purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine administered intramuscularly or intradermally to 12- to 18-month-old Thai children, concomitantly with Japanese encephalitis vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:335-337.

Velasco-Villa A, Reeder SA, Orciari LA, et al. Enzootic rabies elimination from dogs and reemergence in wild terrestrial carnivores, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1849-1854.

Willoughby REJr, Opladen T, Maier T, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency in human rabies. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;32:65-68.

Willoughby RE, Roy-Burman A, Martin KW, et al. Generalized cranial artery spasm in human rabies. Dev Biol (Basel). 2008;131:367-375.