179 Rabies

• Prevention of rabies through postexposure prophylaxis is the main treatment and the only one proven to be beneficial.

• Once signs or symptoms of rabies manifest, the disease is nearly 100% fatal.

• The postexposure prophylaxis regimen recommended by the World Health Organization should not be modified in any way.

• Initiate prophylaxis for any high-risk exposure, even if the wound is healed and the event is remote.

• Treatment of symptomatic rabies is experimental and requires consultation with the health department, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or an infectious disease specialist. It should not begin in the emergency department.

Perspective

Rabies in humans remains rare in the United States. Only 36 cases were reported in the United States in the 20 years from 1980 to 2000,1,2 but rabies exposures in the United States require that approximately 40,000 people receive postexposure prophylaxis annually.3 Human rabies cases in the United States continue to occur, with 2 cases detected in 2008, 4 in 2009, and 1 in 2010.4 International travelers are at increased risk of exposure to rabies and may return to the United States to receive postexposure prophylaxis or rabies treatment. Rabies is a fatal disease.1,2,5,6 Only 6 people are known to have survived the disease.7–13 The low rate of occurrence of the disease challenges physicians to consider this in the differential diagnosis of encephalitides.

Postexposure prophylaxis, if started before clinical signs of rabies develop, is highly effective. With strict adherence to protocol, including wound care, passive immunization, and vaccination with a cell culture vaccine, postexposure prophylaxis prevents rabies.2,14–16 Emergency physicians (EPs) should know when to begin rabies postexposure prophylaxis, when to delay it, and when postexposure prophylaxis is not indicated, and they should also know state and local resources for rabies information.

Anatomy

Rabies is transmitted when saliva or neural tissue from an infected host contacts open wounds or mucous membranes of a recipient. This transmission can occur through bites, aerosolized tissue, or tissue transplantation. Rabies virus is not transmitted by blood, feces, or urine. Rabies is not transmitted across intact skin.2

Once the virus is in a new host, it performs one of two actions. Some virus replicates at the site of the bite in non-nerve tissue. The virus then enters peripheral nerves and travels to the central nervous system (CNS). Some virus does not replicate at the site, but rather immediately enters the peripheral motor and sensory nerves for transport to the CNS. During this time, the virus is in an eclipse phase, and it is difficult to detect with diagnostic tests.17 The virus travels at speeds of 15 to 100 mm/day by retrograde axoplasmic flow.6 When the virus enters the CNS, the incubation time ends. Incubation times range from 2 weeks to several years, and the average is 2 to 3 months.6,17 Once in the CNS, the virus replicates and spreads by cell-to-cell transfer. The virus then travels by anterograde axoplasmic flow to nervous and non-nervous tissue. At the onset of clinical symptoms, the virus is disseminated throughout the body.

Pathophysiology

The virus causes inflammation in the CNS, both encephalitis and myelitis. Perivascular lymphocytic infiltration occurs with lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and plasma cells. Cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion regions (Negri bodies) in neuronal cells are associated with rabies, but they are not sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of rabies.17 Viral replication in dorsal root ganglia causes ganglionitis, and it is responsible for the first clinical symptoms of the disease.5

Clinical Presentation

The first clinical symptoms of rabies are neuropathic pain, paresthesias, or pruritus at the inoculation site. These symptoms were present in 61% of cases in the United States.5,18 A prodromal, flulike illness may mark the onset of clinical rabies. Brain involvement causes encephalitis, manifesting as delirium with periods of lucidity. Two major clinical forms of the disease exist: furious and paralytic.

Paralytic rabies results in quadriplegia.19 It is more common after the bite of a vampire bat in South America. Peripheral neuropathy is responsible for the paralysis in paralytic rabies. Because peripheral nerves are involved, patients lose deep tendon reflexes. The paralysis occurs in an ascending pattern and is associated with pain and fasciculations. The anal sphincter is involved in the quadriplegia.6 Death results from paralysis of bulbar and respiratory muscles.

Variations

Consider rabies in patients with a clinical presentation of encephalitis.20 Atypical presentation of disease is increasingly acknowledged, but it remains poorly described in the literature. Atypical presentations make the suspicion of rabies very difficult, especially if a clear history of rabies exposure is not presented.

Differential Diagnosis

The furious form of rabies is rapidly progressive and is fatal in 1 to 5 days (Table 179.1). The paralytic form of rabies is more slowly progressive, and patients live for up to a month. However, clinical rabies is considered a fatal disease regardless of the clinical manifestation.

| MOST THREATENING FURIOUS RABIES |

MOST COMMON PARALYTIC RABIES |

|---|---|

Diagnostic Testing

In the early stage of the disease, tests may show negative results.6 The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of rabies is direct fluorescent antibody testing of the brain. Brain biopsy exclusively for the diagnosis of rabies is discouraged.21,22

Multiple testing techniques exist for the diagnosis of rabies during life. Discuss with the pathologist the preferred sample at your institution. Serum, saliva, and skin samples are commonly used, whereas cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and lacrimal fluid are occasionally tested.6,23 Do not withhold empiric antirabies therapy to obtain diagnostic studies.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Rabies Exposure

Patient Instructions

Documentation of discussion with patient regarding need for multiple vaccinations, if PEP initiated

Documentation of discussion with patient regarding need to stay in contact with animal control for animal undergoing observation or for euthanized animal

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PEP, postexposure prophylaxis.

Rabies Transmission

Tips and Tricks

Zoonotic Rabies Reservoirs

| Continent or Geographic Region | Primary Animal Reservoir |

|---|---|

| Africa | Dog, mongoose, antelope |

| Asia | Dog |

| Europe | Fox, bat |

| Middle East | Wolf, dog |

| North America | Fox, skunk, raccoon, bat (insectivorous) |

| South America | Dog, vampire bat |

To assess the likelihood of rabies exposure, it is helpful to know the distribution of rabid animals in the area. The local or state health department can provide information about rabies prevalence and animal vectors. A list of state health department contact numbers is available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rabies/Links/Links.htm. Moreover, the CDC can be contacted at 877-554-4625 after hours or if the local or state health department is unavailable (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rabies/professional/professi.htm).

If the animal involved can carry rabies, determine whether the patient had an exposure (see the “Facts and Formulas” box). Consider any breach in the skin that was caused by teeth to be a bite exposure.2,23 Exposure to aerosolized virus in a laboratory or cave setting constitutes a nonbite exposure. Saliva, neural tissue, or other infectious material contacting open wounds or mucous membranes constitutes an exposure. Contact of infectious material with intact skin does not constitute an exposure, nor does contact with noninfectious material, such as feces, blood, or urine, or petting a rabid animal. Do not provide postexposure prophylaxis to patients who have not had an exposure.2

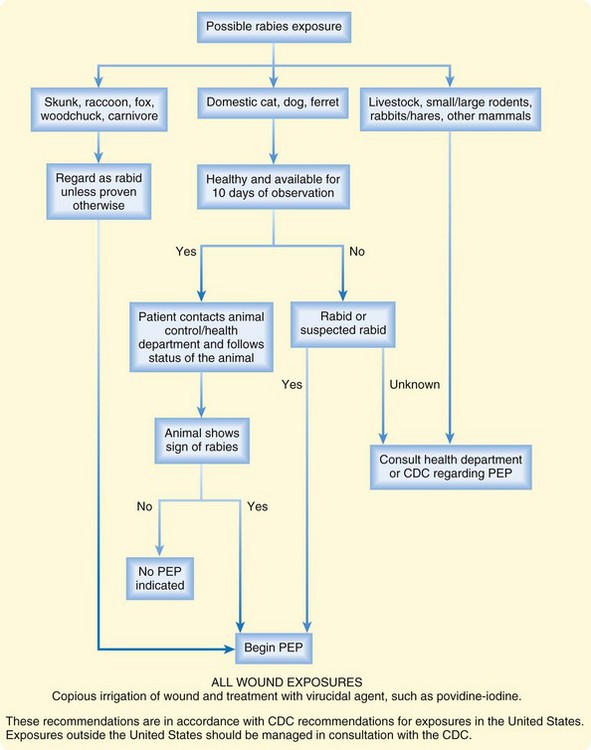

If an exposure has occurred, the decision to begin postexposure prophylaxis is multifactorial. The type of animal, the epidemiology of rabies in the region of the exposure, and the health of the animal all contribute to the decision. Figure 179.1 provides an algorithm for the decision to start postexposure prophylaxis in humans. If an exposure involved a wild animal of a species that is a rabies vector, in a rabies-endemic area, begin postexposure prophylaxis immediately (see the “Tips and Tricks: Postexposure Prophylaxis” box). Do not await laboratory results. If the animal involved is an unlikely vector, postexposure prophylaxis can be withheld in consultation with the health department or CDC, as long as the animal can be tested for rabies, with results available within 48 hours.6

Tips and Tricks

Postexposure Prophylaxis

| Status | Postexposure Prophylaxis Regimen |

|---|---|

| Unvaccinated | Wash the wound thoroughly with soap and water. |

| Treat the wound with a virucidal agent (povidone-iodine). | |

| Administer RIG, 20 units/kg. Infiltrate as much as possible into wound and tissue immediately adjacent to the wound. Administer the remaining dose intramuscularly, remote from the tetanus vaccination site. | |

| Administer 1 mL tetanus vaccine intramuscularly. Use the deltoid muscle in adults. Use the deltoid or anterior thigh in small children. Avoid the site of RIG administration. | |

| Instruct the patient to receive four more vaccinations, on days 3, 7, 14, and 28. | |

| Previously vaccinated | Wash the wound thoroughly with soap and water. |

| Treat the wound with a virucidal agent (povidone-iodine). | |

| Do not administer RIG. | |

| Administer 1 mL tetanus vaccine intramuscularly. Use the deltoid muscle in adults. Use the deltoid or anterior thigh in small children. | |

| Instruct the patient to receive one more vaccination, on day 3. |

RIG, Rabies immune globulin.

If a wild animal that is a potential vector for rabies is responsible for an exposure but is unable to be captured, begin postexposure prophylaxis immediately (see the “Tips and Tricks: Postexposure Prophylaxis” box).6 If a wild animal responsible for an exposure is caught, it should be immediately and humanely euthanized and tested. Wild animals should never be observed for signs of rabies because the time course of rabies in mammals other than dogs, ferrets, cats, and humans is not understood.6

Bats are common wildlife reservoirs of rabies in the United States, and prophylaxis is indicated even after seemingly trivial exposure. Rabies has been transmitted from unimportant or unrecognized exposures to bats.2 Consider direct human-to-bat contact to be a likely exposure, even in the absence of a known bite. Begin rabies postexposure prophylaxis on all bites, scratches, and mucous membrane exposures to bats. Strongly consider postexposure prophylaxis in anyone who has had contact with a bat, even people who may be unaware of injury.2 Strongly consider postexposure prophylaxis in a person who is near a bat and is uncertain whether contact has occurred, such as a person who awakens in a room with a bat.24

If the animal responsible for an exposure is a pet cat, dog, or ferret that is not currently showing signs of rabies, the animal can be observed for 10 days under the care of a veterinarian.25,26 A currently vaccinated dog or cat is unlikely to have rabies, but vaccination failures have been reported. Therefore, even vaccinated animals should be reported to the health department for observation.6

In the case of a healthy, known pet that is not suspected of having rabies, provide the patient with information regarding the local health department and the need for animal quarantine by local animal control. The patient bears the responsibility of maintaining contact with the health department and animal control regarding the status of the animal. EPs are not expected to perform these functions for the patient. The CDC considers postexposure prophylaxis a medical urgency, not an emergency. Therefore, it is reasonable, in the low-risk exposures outlined in Figure 179.1, to delay postexposure prophylaxis. In this case, the patient will follow up with the health department or animal control and will return to a physician for postexposure prophylaxis, based on the finding in the animal.2

Travel Outside the United States

The World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/rabies/epidemiology) reports that rabies is present on every continent except Antarctica. Of 145 countries reporting, 45 note no cases of rabies. These rabies-free countries include selected islands such as New Zealand, Japan, Fiji, and Barbados, as well as certain developed European countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Scandinavian countries. In Latin America, Chile and Uruguay are noted to be free of rabies.

Human-to-human transmission of rabies is possible. Documented cases have involved inoculation through saliva by biting or kissing.27 Human-to-human transmission has also occurred from the transplantation of infected organs.28,29 When providing routine health care to a person with rabies, the use of appropriate contact isolation practices prevents rabies exposure in the health care provider.2,30 No known case of transmission of rabies to a health care worker from a patient exists.5 Treat persons who have been stuck with a contaminated needle from a patient with rabies as a rabies exposure. The concern is that the needle may contain neural tissue.

Incubation periods of up to 6 years have been reported for rabies.17 For this reason, if exposure to rabies may have occurred, start postexposure prophylaxis regardless of the time from the exposure.6 Adhere to the postexposure prophylaxis protocol as with any other exposure (see the “Tips and Tricks: Postexposure Prophylaxis” box).

Wound Treatment and Rabies Prevention

Postexposure prophylaxis consists of three steps: wound care, conferring of passive immunity, and active immunization. When World Health Organization guidelines for postexposure prophylaxis are followed, postexposure prophylaxis is effective. Postexposure prophylaxis failures have all involved deviation from the guidelines.2

The first step in rabies postexposure prophylaxis is local wound care. Copiously irrigate the wound with soap and water. Follow with treatment with a virucidal agent, such as povidone-iodine. Wound care alone decreases the chance of contracting rabies.31 Failures of postexposure prophylaxis have been attributed to inadequate local wound care.2

If the patient presents with a bite or wound that is already infected, clean the wound appropriately. Débride and incise the wound as needed. RIG can be infiltrated safely into an infected wound following proper local wound care.6

Administer 1 mL of vaccine intramuscularly. The vaccine is administered intramuscularly into the deltoid muscle of adults. The vaccine can be administered intramuscularly into the deltoid or anterior thigh of a child. Vaccine failures have been recorded for administration of vaccine into sites other than the deltoid of adults.32 Do not administer vaccine into the same intramuscular region as RIG was administered. Do not use the same syringe to administer vaccine and RIG.

Because rabies is considered a fatal disease, postexposure prophylaxis is not withheld during pregnancy. Inform pregnant patients that no known fetal anomalies have been linked to rabies postexposure prophylaxis,33–35 but extensive testing in humans has not been performed. When possible, discuss the case with the patient’s obstetrician.

Treatment

Rabies is considered a fatal disease.5 Only six known cases of survivors of clinical rabies have been reported, and in five of these cases, patients had some form of rabies immunization before the onset of clinical disease. Four of the six survivors had neurologic devastation.8–11

Symptomatic Rabies

Once clinical signs or symptoms of rabies have begun, no reliably successful rabies treatment is known. Treatments are all considered experimental and have included antiviral therapy with ribavirin, vidarabine, and interferon alfa.5,36,37 Rabies vaccine has not been demonstrated to have a beneficial effect in animal models when it is administered after the onset of clinical disease. RIG is of unknown benefit in clinical disease, but it is administered.5 Ketamine has been used to induce coma and has been shown to decrease viral replication in rat models. This drug is of unknown clinical benefit in humans.38 Corticosteroids are associated with increased mortality in laboratory studies. Avoid corticosteroids in patients suspected of having rabies encephalitis.5 Because of the lack of an effective therapeutic regimen, the treatment of rabies involves consultation with local or state health departments and the CDC, in conjunction with an infectious disease specialist and intensive care specialist, when available. The responsibility of the EP is to maintain a level of suspicion for rabies in a patient with signs of encephalitis, to consult for definitive diagnosis and management of rabies, and to provide supportive care while the patient is in the emergency department (ED). The determination of an effective antiviral regimen for a patient with suspected or confirmed rabies is outside the scope of practice of emergency medicine.

When rabies is suspected, consult the local or state health department, the CDC, or an infectious disease specialist for emergency treatment guidance. Give RIG, 20 units/kg intramuscularly, if significant delay in consultation is encountered. Provide supportive care to the patient. Spasms are painful, and the patient remains aware through much of the clinical course of the disease. When it is not contraindicated because of other comorbidities, administer ketamine by continuous intravenous infusion to sedate the patient and to alleviate the pain of rabies.5 Intubate the patient if the patient has lost protective airway responses as a result of progression of the disease or because of sedation from medications. Unlike in bacterial infectious emergencies, delay in beginning antiviral agents is acceptable. Because of the lack of a standard of care in the treatment of rabies, the decision to begin antiviral therapy is best made in conjunction with consultants.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Clinical Rabies

Studies

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Clinical Rabies

Assess the patient for rabies exposure.

If exposure is likely or possible, contact the health department or the CDC for treatment recommendations.

Consult an infectious disease specialist, when available.

Consult an intensive care specialist.

Administer rabies immune globulin, 20 units/kg intramuscularly, if obtaining consultant recommendations is delayed.

Administer ketamine by intravenous infusion if the patient is in pain or is experiencing agitation.

Have the patient admitted by an intensive care specialist.

Defer vaccine administration and antiviral therapy to the health department or CDC or an infectious disease specialist.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Avoid contact with bats, including prevention of bat colonies.

Seek medical care after exposure to bats.

Avoid direct contact with wildlife.

Avoid contact with any ill-appearing animal and with animals exhibiting bizarre behavior.

Do not approach unknown cats or dogs.

Seek medical attention for domestic animal bites.

Any person bitten by a wild animal should seek medical attention.

1 Noah DL, Drenzek CL, Smith JS, et al. Epidemiology of human rabies in the United States, 1980-1996. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:922–930.

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Rabies Prevention: United States, 1999 recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 1999;48:1–21.

3 Krebs JW, Long-Marin SC, Childs JE. Causes, costs and estimates of rabies postexposure prophylaxis treatments in the United Sates. J Public Health Manage Pract. 1998;4:57–63.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human rabies surveillance data. http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/human_rabies.html.

5 Jackson AC, Warrell MJ, Rupprecht CE, et al. Management of rabies in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:60–63.

6 World Health Organization. WHO expert consultation on rabies. First report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. pp. 1-121

7 Gode GR, Raju AV, Jayalakshmi TS, et al. Intensive care in rabies therapy: clinical observations. Lancet. 1976;2:6–8.

8 Hattwick MA, Weis TT, Stechschulte CJ, et al. Recovery from rabies: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 1972;76:931–942.

9 Tillotson JR, Axelrod D, Lyman DO. Rabies in a laboratory worker: New York. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1977;26:183–184.

10 Porras C, Barboza JJ, Fuenzalida E, et al. Recovery from rabies in man. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:44–48.

11 Alvarez L, Fajardo R, Lopez E, et al. Partial recovery from rabies in a nine-year-old boy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:1154–1155.

12 Madhusudana SN, Nagaraj D, Uday M, et al. Partial recovery from rabies in a six-year-old girl [letter]. Int J Infect Dis. 2002;6:85–86.

13 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recovery of a patient from clinical rabies: Wisconsin, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1171–1173.

14 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rabies. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rabies/.

15 Anderson LJ, Sikes RK, Langkop CW, et al. Postexposure trial of human diploid cell strain rabies vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:133–138.

16 Bahmanyar M, Fayaz A, Nour-Salehi S, et al. Successful protection of humans exposed to rabies infection: postexposure treatment with the new human diploid cell rabies vaccine and antirabies serum. JAMA. 1976;236:2751–2754.

17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rabies: natural history. www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rabies/natural_history/nathist.htm.

18 Messenger SL, Smith JS, Rupprecht CE. Emerging epidemiology of bat-associated cryptic cases of rabies in humans in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:738–747.

19 Jackson AC. Human disease. In: Jackson AC, Wunner WH. Rabies. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002:219–244.

20 Rupprecht CE, Hemachudha T. Rabies. In: Scheld M, Whitley RJ, Marra C. Infections of the central nervous system. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:243–259.

21 Hemachudha T, Wacharapluesadee S. Ante-mortem diagnosis of human rabies. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1085–1086.

22 Hanlon CA, Smith JS, Anderson GR. Recommendations of a national working group on prevention and control of rabies in the Unites States. Article II: laboratory diagnosis of rabies. The National Working Group on Rabies Prevention and Control. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215:1444–1447.

23 Bourhy H, Rollin PE, Vincent J, Sureau P. Comparative field evaluation of the fluorescent-antibody test, virus isolation from tissue culture, and enzyme immunodiagnosis for rapid diagnosis of rabies. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:519–523.

24 Feder HM, Nelson R, Reiher HW. Bat bite? Lancet. 1997;350:1300.

25 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Imported dog and cat rabies: New Hampshire, California. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:559–560.

26 Niezgoda M, Briggs DJ, Shaddock J, et al. Pathogenesis of experimentally induced rabies in domestic ferrets. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:1327–1331.

27 Fekadu M, Endshaw T, Wondimagegnehu A, et al. Possible human-to-human transmission of rabies in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 1996;34:123–127.

28 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigation of rabies infections in organ donor and transplant recipients: Alabama, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1–3.

29 World Health Organization. Two rabies cases following corneal transplantation. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1994;69:330.

30 Garner JS. Guidelines for isolation precautions in hospitals: the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996;17:53–80.

31 Kaplan MM, Cohen D, Koprowski H, et al. Studies on the local treatment of wounds for the prevention of rabies. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;26:765–775.

32 Fishbein DB, Sawyer LA, Reid Sanden FL, Weir EH. Administration of human diploid-cell rabies vaccine in the gluteal area. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:124–125.

33 Chutivonse S, Wilde H, Benjavongkulchai M, et al. Postexposure rabies vaccination during pregnancy: effect on 202 women and their infants. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:818–820.

34 Varner MW, McGuinness GA, Galask RP. Rabies vaccination in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;143:717–718.

35 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 282, January 2003: immunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:207–212.

36 Warrell MJ, White NJ, Looareesuwan S, et al. Failure of interferon alpha and ribavirin in rabies encephalitis. BMJ. 1989;299:830–833.

37 Dolman CL, Charlton KM. Massive necrosis of the brain in rabies. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14:162–165.

38 Lockhart BP, Tordo N, Tsiang H. Inhibition of rabies virus transcription in rat cortical neurons with the dissociative anesthetic ketamine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1750–1755.