Chapter 2 Quality and Safety in Health Care for Children

What is Quality?

Definitions of Quality-Related Terms

Quality includes many concepts—quality measurement, quality reporting and benchmarking, process improvement, performance, and outcomes improvement using quality initiatives (Table 2-1).

Table 2-1 DEFINITIONS OF QUALITY-RELATED TERMS

Quality “… the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” U.S. Institute of Medicine

Quality Initiative “… systematic, data-guided activities designed to bring about immediate improvements in health care delivery in particular settings.” Hastings Center

Performance Measure “… yardsticks by which all health care providers and organizations can determine how successful they are in delivering recommended care and improving patient outcomes.” U.S. Institute of Medicine

Performance Management “… a systematic process by which an organization involves its employees in improving the effectiveness of the organization and achieving the organization’s mission and strategic goals. By improving performance and quality, public health systems can save lives, cut costs, and get better results by managing performance.” Public Health Foundation

Process Improvement “… the systematic approach to closing of process or system performance gaps through streamlining and cycle time reduction, and identification and elimination of causes of below specifications quality, process variation, and non-value-adding activities.” BusinessDictionary.com

Measuring Quality

Robust quality indictors should have clinical and statistical relevance. Clinical relevance ensures that the indicators are meaningful in patient care from the standpoint of patients and clinicians. Statistical relevance ensures that the indicators have measurement properties to allow an acceptable level of accuracy and precision. These concepts are captured in the national recommendations that quality measures must meet the criteria of being valid, reliable, feasible, and usable (Table 2-2). Validity of quality measures relates to the notion that the measure is estimating the true concept of interest. Reliability relates to the notion that the measure is reproducible and provides the same result if retested. It is important that quality measures are feasible in practice. Quality measures must be useable, which means that they should be clinically meaningful. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has provided specific criteria to be considered when developing quality measures.

| ATTRIBUTE | RELEVANCE |

|---|---|

| Validity | Indicator accurately captures the concept being measured. |

| Reliability | Measure is reproducible. |

| Feasibility | Data can be collected using paper or electronic records. |

| Usability | Measure is useful in clinical practice. |

Pediatric quality measures are being developed nationally. Table 2-3 provides a list of some of the important currently endorsed pediatric national quality indicators.

Table 2-3 NATIONAL PEDIATRIC QUALITY MEASURES

| NQF PDIs (2008) | NQF-ENDORSED INPATIENT MEASURES AMONG PICUs | NQF-ENDORSED CHIPRA MEASURES (2009) |

|---|---|---|

| Accidental puncture or laceration | PICU standardized mortality ratio | Childhood immunization status |

| Decubitus ulcer | PICU severity adjusted length of stay | Appropriate testing for children with pharyngitis |

| Foreign body left after procedure, age under 18 yr | Unplanned PICU readmission (readmissions within 24 hr after discharge/transfer from PICU) | Chlamydia screening in women |

| Iatrogenic pneumothorax in non-neonates | Review of unplanned PICU readmissions | Follow-up/mental illness |

| Pediatric heart surgery mortality | PICU pain assessment on admission | Follow-up/ADHD medication |

| Pediatric heart surgery volume | PICU periodic pain assessment (minimum of every 6 hr) | HEDIS CAHPS/chronic conditions |

| Postoperative wound dehiscence, age under 18 yr | Catheter-associated bloodstream infections | Weight assessment and counseling |

| Transfusion reaction, age under 18 yr |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CAHPS, Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; CHIPRA, Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act; HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; NQF, National Quality Forum; PDIs, pediatric quality indicators; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

Comparing and Reporting Quality

Risk adjustment can be performed at 3 levels. First, patients who are sicker can be excluded from the analysis, thereby allowing the comparisons to be within homogenous groups. Although this approach is relatively simple to use, it is limited in that it would result in patient groups being excluded from the analysis. Second, risk stratification can be performed using measures of patient acuity. An example of this relates to the use of the APR-DRG (All-Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group) system where patients can be grouped or stratified into different severity criteria based on acuity weights. This approach may provide relatively homogenous strata within which comparisons can be performed, but it is not able to predict the overall outcomes within patient risk groups. Third, severity of illness risk adjustment relates to the use of clinical data to predict the outcomes of patient groups. An example of a clinical severity of illness risk adjustment process is the use of the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) scoring system in the PICU setting (Chapter 61). The PRISM score, and its subsequent iterations, composed of a combination of physiologic and laboratory perimeters that are weighted on a statistical logistic scale to predict the risk of mortality within that PICU stay. By comparing the observed and expected outcomes (i.e., mortality or survival), a quantitative estimate of the performance of that PICU can be established which can then be used to compare outcomes with other PICUs (standardized mortality ratio).

Improving Quality

Model for Improvement

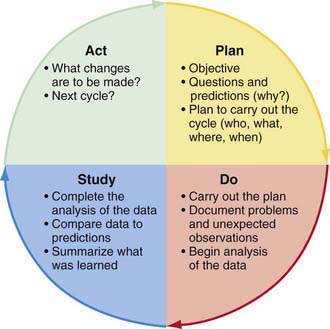

The Model for Improvement can be implemented using a framework of rapid cycle improvement also known as the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle (Fig. 2-1). The PDSA cycle is typically aimed at testing small changes and then studying the results to plan and implement the next cycle of change (i.e., multiple PDSA cycles build on previous learnings from PDSAs). Valuable information can be obtained from PDSA cycles that are successful and those that are not, to help plan the next iteration of the PDSA cycle. The PDSA cycle specifically requires that improvements be data driven. This is important because many clinicians attempt to make changes for improvement in their practice but do not emphasize the importance of data collection.

Figure 2-1 The Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle.

(From Langley GJ: The improvement guide: a practical guide to enhancing organizational performance, San Francisco, 1996, Jossey-Bass. © 1996 by Gerald J. Langley, Kevin M. Nolan, Thomas W. Nolan, L. Norman, and Lloyd P. Provost. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

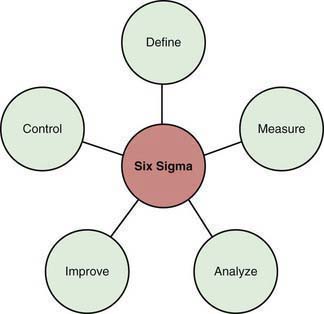

Six Sigma

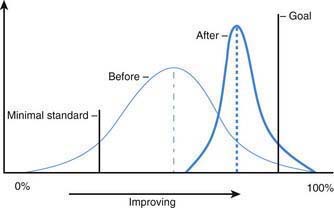

Six Sigma relates to the reduction in undesirable variation in processes (Fig. 2-2). Every process has some level of inherent variation built into it. There are 2 types of variations in a process. Random variation relates to the variation that is inherent in the process simply due to the fact that the process is being performed by humans. A physician completing a history and physical for a patient more than once may have a slightly different process each time, even though it is the same patient and the same physician. Random variation in processes is acceptable. In contrast, special cause variation relates to nonrandom variation that can adversely affect a process; when tracking infection rates in a nursery, a sudden increase in the infection rates may be secondary to poor handwashing techniques by a new health care provider in the system. This would represent a special cause variation (i.e., once this practice is improved, the infection rates will likely go back to the baseline level). Six Sigma attempts to provide a structured approach to unwanted variations in health care processes (Fig. 2-3). Six Sigma approaches have been successfully used in health care to improve processes in both the clinical and nonclinical settings.

LEAN

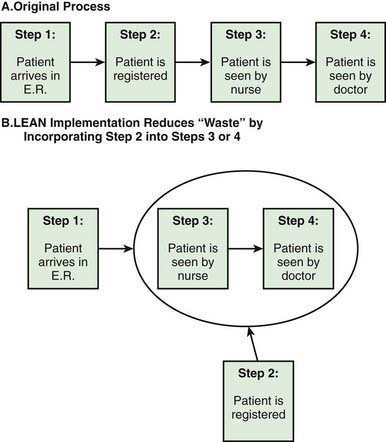

LEAN Methodology, which stems from the Toyota Production System, aims at reducing waste within a process in a system. Figure 2-4A illustrates the steps in the process of a patient coming to the emergency department. After the initial registration, the patient is seen by a nurse and then the physician. In a busy emergency department, a patient may need to wait for hours before registration is complete and the patient is placed in the examination room. This wait time is a waste from the perspective of the patient and the family; by incorporating the registration process after placing the patient in the physician examination room, time can be saved and waste minimized (Fig. 2-4B). LEAN methods have been successfully used in several outpatient and inpatient settings with resulting improvements in efficiency. LEAN principles have also been adopted as a core strategy for children’s hospitals with the goal of improving efficiencies and reducing waste.

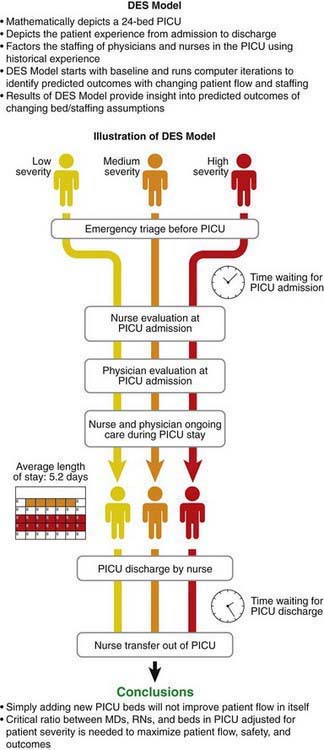

Management Sciences

Management Sciences (MS), also known as Operations Management, stems from operations research and relates to the use of mathematical principles to maximize efficiencies within systems. MS has been successfully used in many non–health care settings such as airlines and the military. MS principles have been successful in many European health care settings to optimize efficiencies in outpatient primary care office settings, inpatient acute care hospital settings, surgical settings including operating rooms, and also for effective planning of transport and hospital expansion policies. MS principles are being explored for use in the U.S. health care system. One of the techniques for MS, Discrete Event Simulation (DES) was used at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin to effectively plan the expansion of the pediatric critical care services with the goal of improving quality and safety. The DES model illustrated in Figure 2-5 depicts the various steps of the process in a PICU. Patients stratified across 3 levels of severity (low, medium, high) are admitted to the PICU, are initially seen by a nurse and physician, and then stay in the PICU with ongoing care being provided by physicians and nurses, and are finally discharged from the PICU. The DES model illustrated in Figure 2-5 is a computer model developed using real estimates of numbers of patients, numbers of physicians and nurses in a PICU, and patient outcomes. DES models are created using real historical data, which allows testing the “what if” scenarios, such as the impact on patient flow and throughput by increasing the number of beds and/or changing nurse and physician staffing.

Figure 2-5 Management Sciences—Discrete Event Stimulation (DES). PICU, pediatric intensive care unit.

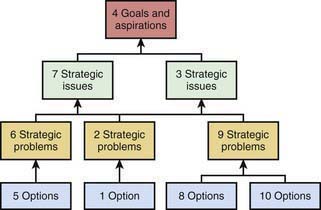

Another MS technique developed in Europe relates to the concept of Cognitive Mapping. Cognitive Mapping aims at measuring the soft aspects of MS as illustrated in Figure 2-6. Cognitive Mapping highlights the importance of perceptions and constructs of health care providers and how these constructs are linked in a hierarchical manner. Goals and aspirations of individual health care providers are identified by structured interviews and are mapped to strategic issues and problems, and options. By using specialized computer software, complex relationships can be identified to better understand the relationships between different constructs in a system. A DES model views patient throughput based on numbers of beds, physicians, and nurses and accounts for differences in patient mix. It does not account for many other factors such as individual unit characteristics related to culture. By interviewing health care providers, Cognitive Maps can be developed that can help to better inform decision-making.

Quality and Patient Safety

Key Issues in Patient Safety

Making care safer requires the identification and control of things that could cause harm to patients. Several key concepts regarding patient safety are summarized in the following sections and are available in curriculum overviews at www.patientsafety.gov, www.npsf.org, and www.va.gov.

A Comprehensive Model for Quality Improvement—Experience from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

In addition to the AAP, there are other national organizations that are actively working with physicians and hospitals to provide resources for quality improvement in health care for children (Table 2-4).

Table 2-4 NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN PEDIATRIC QUALITY IMPROVEMENT (QI)

| ORGANIZATION | ROLE | ACTIVITIES |

|---|---|---|

| American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) | Representing over 60,000 pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists worldwide | Resources for QI to improve health for all children, best practices, advocacy, policy, research and practice, and medical home |

| American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) | Certifying board for pediatrics and pediatric subspecialties | Certification policies and resources for activities such as Maintenance of Certification (MOC) |

| National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Organizations (NACHRI) | Association of children’s hospitals and pediatric institutions | Databases, QI collaboratives, and policy |

| Child Health Corporation of America (CHCA) | Association of children’s hospitals | Databases and QI collaboratives |

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) | QI organization for adult and pediatric care | QI collaboratives, QI educational workshops and materials |

| National Initiative for Child Health Quality (NICHQ) | QI organization for pediatric care | QI training, improvement networks |

| Joint Commission | Hospital accreditation organization | Unannounced surveys to evaluate quality of care in hospitals |

| National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) | QI organization | Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and quality measures for improvement |

| National Quality Forum (NQF) | Multidisciplinary group including health care providers, purchases, consumers, and accrediting bodies | Endorsing national quality measures, convening expert groups, and setting national priorities |

| American Medical Association (AMA) | Physician member association | Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI)—physician-led initiative |

Courtlandt CD, Noonan L, Field LG. Model for improvement—part 1: a framework for health care quality. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:757-778.

Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(Suppl 3):166-206.

Goldstein MM, Blumenthal D. Building an information technology infrastructure. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36(4):709-715.

Guidelines for consumer-focused public reporting (PowerPoint file). www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/downloads/usermeeting2008/Cronin_Consumer%20focused%20public%20reporting.ppt. Accessed February 10, 2009

Harbaugh NJr. Pay for performance: quality-and-value-based reimbursement. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:997-1007.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

Kurtin P, Stucky E. Standardize to excellence: improving the quality and safety of care with clinical pathways. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:893-904.

LaRovere JM, Jeffries HE, Sachdeva RC, et al. Databases for assessing the outcomes of the treatment of patients with congenital and paediatric cardiac disease—the perspective of critical care. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl. 2):130-136.

Mandel KE, Muething SE, Schoettker PJ, et al. Transforming safety and effectiveness in pediatric hospital care locally and nationally. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:905-918.

Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1515-1523.

Margolis P, Provost LP, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement, clinical research, and quality improvement research—opportunities for integration. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:831-841.

McDonald KM. Approach to improving quality: the role of quality measurement and a case study of the agency for healthcare research and quality pediatric quality indicators. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:815-829.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635-2645.

Miles P. Health information systems and physician quality: role of the American Board of Pediatrics maintenance of certification in improving children’s health care. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S108-S110.

Miles PV. Maintenance of certification: the role of the American Board of Pediatrics in improving children’s health care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:987-994.

Miller FG, Emanuel EJ. Quality-improvement research and informed consent. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:765-767.

Neuspiel DR, Hyman D, Lane M. Quality improvement and patient safety in the pediatric ambulatory setting: current knowledge and implications for residency training. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:935-951.

Pay for performance improving health care quality and changing provider behavior; but challenges persist (website). www.rwjf.org/newsroom/newsreleasesdetail.jsp?productid=21847. Accessed February 10, 2009

Pollack MM, Ruttimann UE, Getson PR. Pediatric risk of mortality (PRISM) score. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:1110-1116.

Randolph G, Esporas M, Provost L, et al. Model for improvement—part 2: measurement and feedback for quality improvement efforts. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:779-798.

Sachdeva RC. Electronic healthcare data collection and pay-for-performance: translating theory into practice. Ann Health Law. 2007;16(2):291-311.

Sachdeva RC, Jain S. Making the case to improve quality and reduce costs in pediatric health care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56(4):731-743.

Sachdeva RC, Kuhn EM, Gall CM, et al. A need for development of diagnosis-specific severity of illness tools for risk adjustment [abstract]. Crit Care Med. 2009;36(12)Suppl):A83.

Sax HC, Browne P, Mayewski RJ, et al. Solutions for improving patient safety. JAMA. 2010;303:159-161.

Scanlon MC, Harris JMII, Levy F, et al. Evaluation of the agency for healthcare research and quality pediatric quality indicators. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1723-e1731.

Schulman J, Wirtschafter DD, Kurtin P. Neonatal intensive care unit collaboration to decrease hospital-acquired bloodstream infections: from comparative performance reports to improvement networks. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:865-892.

Simpson LA, Fairbrother G. How health policy influences quality of care in pediatrics. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:1009-1021.

Stapleton FB, Hendricks J, Hagan P, et al. Modifying the Toyota production system for continuous performance improvement in an academic children’s hospital. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:799-813.

Takata GS, Mason W, Taketomo C, et al. Development, testing, and findings of a pediatric-focused trigger tool to identify medication-related harm in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e927-e935.

Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, et al. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in medicare managed care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:692-700.

Varni JW, Limbers CA. The pediatric quality of life inventory: measuring pediatric health-related quality of life from the perspective of children and their parents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:843-868.

Wegner SE, Antonelli RC, Turchi RM. The medical home—improving quality of primary care for children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:953-964.

Zuckerman AE. The role of health information technology in quality improvement in pediatrics. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:965-973.