Pyloromyotomy for Pyloric Stenosis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Pyloric Stenosis

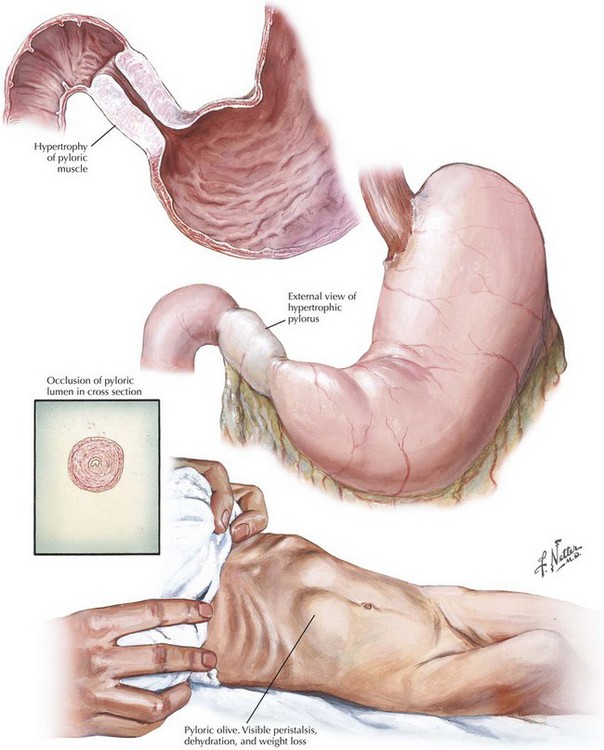

A diagnosis of pyloric stenosis depends on both patient history and physical examination. Most patients will initially be seen with progressive, nonbilious projectile vomiting at 2 to 8 weeks of age. Patients may show signs of metabolic alkalosis, dehydration, and malnutrition, depending on duration of symptoms. On examination, visible peristaltic waves at the epigastrium and a palpable mass in the left upper quadrant may be present when the abdominal wall is relaxed. The mass is typically olive shaped, smooth, hard, and about 1 to 2 cm in size (Fig. 10-1). The hypertrophied pylorus can also be appreciated using ultrasonography or an upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast study.

Preoperative Imaging of Pyloric Stenosis

The ultrasonographic criteria for pyloric stenosis include an elongated pyloric channel (14 to 20 mm), an enlarged pyloric diameter (>12 mm), and a thickened muscle wall (>3 mm) (Fig. 10-2, A). A contrast study will demonstrate a distended stomach with a narrowed and elongated pyloric channel. These findings are often referred to as the “string” sign or “double track” sign. Upper GI studies can also show “shoulders” at the proximal end of the pylorus, indicating the hypertrophied muscle bulging into the gastric lumen, and a pyloric “beak” at the pyloric entrance to the antrum (Fig. 10-2, B).

Open Surgical Approach

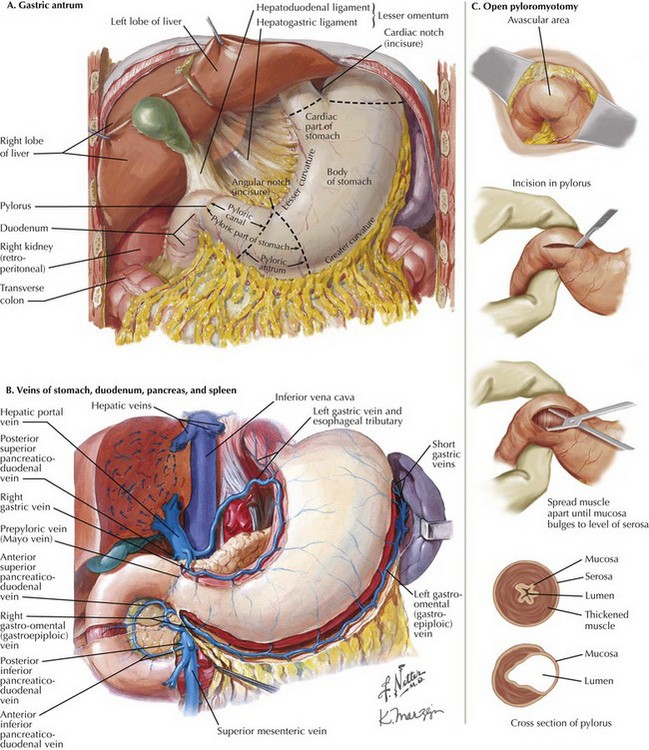

The open pyloromyotomy can be performed through a small, right upper quadrant incision. Alternatively, the surgeon may choose to enter the abdomen through a circumbilical incision. With this technique, an omega-shaped incision is made in a supraumbilical skin fold, through which the midline fascia is identified and exposed one-third to one-half the distance from the umbilicus to the xiphoid. To visualize the pylorus, the omentum must first be mobilized using gentle traction, thereby exposing the transverse colon. With the transverse colon displaced caudally, the gastric antrum is visible (Fig. 10-3, A).

Gently grasping the greater curvature of the stomach with a sponge, the surgeon brings the pylorus into the wound by inferior and lateral traction on the stomach. The surgeon identifies the gastroduodenal junction by the prepyloric vein (Fig. 10-3, B). The surgeon secures the duodenal portion of the pylorus with the index finger of the nondominant hand and makes a 1- to 2-cm longitudinal incision along the plane of the transverse muscle fibers, from the proximal thickening of the muscle to within 3 mm of the antrum. The incision is taken through the serosal and muscle layers using blunt dissection, then widened using a Benson spreader until the submucosa bulges into the cleft (Fig. 10-3, C). Care should be taken to avoid injury to the distal pylorus, because the duodenal mucosa is fragile.

Laparoscopic Approach

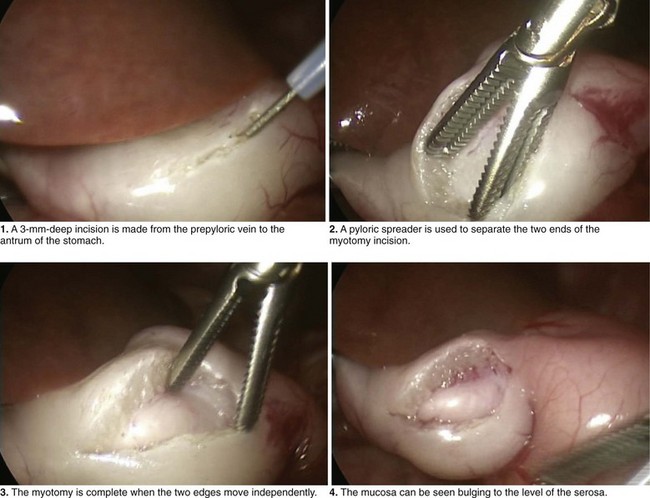

The umbilicus is entered bluntly with a fine mosquito clamp. A 3-mm, 4-mm, or 5-mm trocar, followed by a 30-degree telescope, is inserted through the umbilicus, and two 3-mm stab incisions are created in the left and right epigastrium (Fig. 10-4). A knife blade exposed to no more than 3 mm, or an extended-length, insulated Bovie electrocautery device with 3 mm of exposed blade, is placed in the left upper quadrant incision, while a pyloric grasper is inserted into the right upper quadrant incision. The grasper is used to secure the distal pylorus, and an incision is made along the anterior surface of the pylorus, extending from the prepyloric vein to the antrum of the stomach. The blunt blade of the knife or cautery blade is pushed into the myotomy incision, then rotated 60 to 90 degrees, thereby breaking down the muscular wall. As the incision is made deeper, the knife is replaced by the pyloric spreader. The myotomy is complete when the two cut edges move independently (Fig. 10-4).

Adibe, O, Nichol, P, Flake, A, Mattei, P. Comparisons of outcomes after laparoscopic and open pyloromyotomy at a high volume pediatric teaching hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(10):1676–1678.

Aspelund, G, Langer, J. Current management of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:27–33.

Bufo, AJ, Merry, C, Shah, R, et al. Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy: a safer technique. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13(4):240–242.

Campbell, BT, McLean, K, Barnhart, DC, Drongowski, RA, Hirschl, RB. A comparison of laparoscopic and open pyloromyotomy at a teaching hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(7):1068–1071.

Hall, NJ, Ade-Ajayi, N, Al-Roubaie, J, et al. Retrospective comparison of open versus laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. Br J Surg. 2004;91(10):1325–1329.

Hussain, M. Sonographic diagnosis of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: use of simultaneous grey-scale and colour Doppler examination. Int J Health Sci. 2008;2(2):143–150.

St Peter, SD, Holcomb, GW, 3rd., Calkins, CM, et al. Open versus laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for pyloric stenosis: a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):363–370.