Chapter 321 Pyloric Stenosis and Other Congenital Anomalies of the Stomach

321.1 Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Clinical Manifestations

The diagnosis has traditionally been established by palpating the pyloric mass. The mass is firm, movable, ∼2 cm in length, olive shaped, hard, best palpated from the left side, and located above and to the right of the umbilicus in the mid-epigastrium beneath the liver’s edge. The olive is easiest palpated after an episode of vomiting. After feeding, there may be a visible gastric peristaltic wave that progresses across the abdomen (Fig. 321-1).

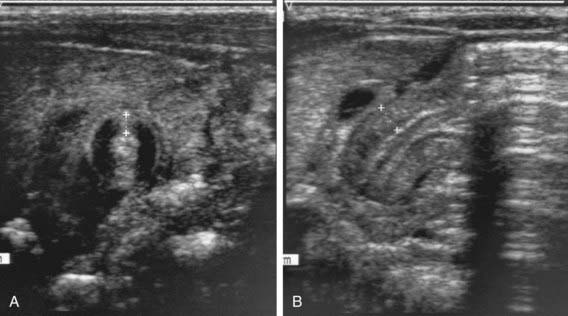

Two imaging studies are commonly used to establish the diagnosis. Ultrasound examination confirms the diagnosis in the majority of cases. Criteria for diagnosis include pyloric thickness 3-4 mm, an overall pyloric length 15-19 mm, and pyloric diameter of 10-14 mm (Fig. 321-2). Ultrasonography has a sensitivity of ∼95%. When contrast studies are performed, they demonstrate an elongated pyloric channel (string sign), a bulge of the pyloric muscle into the antrum (shoulder sign), and parallel streaks of barium seen in the narrowed channel, producing a “double tract sign” (Fig. 321-3).

Differential Diagnosis

Gastric waves are occasionally visible in small, emaciated infants who do not have pyloric stenosis. Infrequently, gastroesophageal reflux, with or without a hiatal hernia, may be confused with pyloric stenosis. Gastroesophageal reflux disease can be differentiated from pyloric stenosis by radiographic studies. Adrenal insufficiency from the adrenogenital syndrome can simulate pyloric stenosis, but the absence of a metabolic acidosis and elevated serum potassium and urinary sodium concentrations of adrenal insufficiency aid in differentiation (Chapter 570). Inborn errors of metabolism can produce recurrent emesis with alkalosis (urea cycle) or acidosis (organic acidemia) and lethargy, coma, or seizures. Vomiting with diarrhea suggests gastroenteritis, but patients with pyloric stenosis occasionally have diarrhea. Rarely, a pyloric membrane or pyloric duplication results in projectile vomiting, visible peristalsis, and, in the case of a duplication, a palpable mass. Duodenal stenosis proximal to the ampulla of Vater results in the clinical features of pyloric stenosis but can be differentiated by the presence of a pyloric mass on physical examination or ultrasonography.

Chung E. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: genes and environment. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:1003.

Kawahara H, Takama Y, Yoshida H, et al. Medical treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: should we always slice the “olive”? J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1848.

Singh UK, Kumar R, Prasad R. Oral atropine sulfate for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:473.

Sorensen HT, Skriver MV, Pedersen L, et al. Risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after maternal postnatal use of macrolides. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:104.

To T, Wajja A, Wales PW, Langer JC. Population demographic indicators associated with incidence of pyloric stenosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:520.

Yagmurlu A. Laparoscopic versus open pyloromyotomy. Lancet. 2009;373:358-360.

321.5 Hypertrophic Gastropathy

Graham-Maar RC, Russo P, Johnson AM, et al. A 2-year-old boy with emesis and facial edema. Med Gen Med. 2006;8:75.

Hoffer V, Finkelstein Y, Balter J, et al. Ganciclovir treatment in Ménétrier’s disease. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:983-985.

Megged O, Schlesinger Y. Cytomegalovirus-associated protein-losing gastropathy in childhood. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1217-1220.

Tokuhara D, Okano Y, Asou K, et al. Cytomegalovirus and Helicobacter pylori co-infection in a child with Ménétrier disease. Eur J Ped. 2007;166:63-65.

Watanabe K, Beinborn M, Nagamatsu S, et al. Menetrier’s disease in a patient with Helicobacter pylori infection is linked to elevated glucagon-like peptide-2 activity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:477-481.