CHAPTER 59 Pure aspiration lipoplasty

Physical evaluation

• Take a careful history including discussions of weight changes, pregnancies, and eating disorders.

• Assess the musculo-skeleton for posture, scoliosis, overall body curves, and body type. Note asymmetries and point them out to the patient.

• Determine areas of maximal fat deposition and disproportion. Localized excess and disproportionate fat deposits increase the likelihood of the surgeon being able to produce visually striking contour reductions. Conversely, diffuse fat distribution, with or without obesity, makes it difficult to obtain quality results.

• Assess skin tone for laxity, wrinkles, striae, dimples, fatty bulges and skin folds.

• Determine thickness of fat in all potential treatment areas using the pinch test with and without voluntary underlying muscle contraction.

• Estimate volume of aspirate from each potential treatment area.

• Calculate estimated total volume of estimated aspirate from all areas to plan a safe operation and smooth postoperative course.

• Examine the patient, both standing and supine, to assess the abdomen for muscle weaknesses or hernias.

• Evaluate expectations. Is the goal improvement and not perfection? Educate the patient that liposuction is a superb sculptural technique for changing body proportions, but is not an effective weight loss modality or a substitute for a healthy diet and lifestyle.

Anatomy

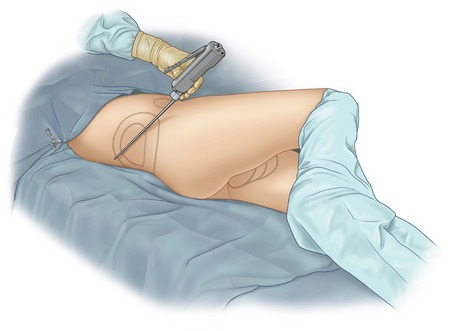

The subcutaneous fat is divided into superficial and deep layers. Zones of adherence, such as the iliac crest, create the boundaries that define fatty bulges. When the tumescent technique is employed with liposuction, infusion of fluid enlarges the subcutaneous space, creating a larger safe zone for liposuction between the skin and the underlying musculature. Discontinuous aspiration in the subcutaneous space extracts the loosely attached fat, leaving intact the small neurovascular bundles and fascial attachments of the skin to the muscle (Fig. 59.1). The elasticity of the dermis and underlying fascial attachments determine the degree of skin tightening over the newly contoured subcutaneous tissues. There is no evidence that skin tightening is increased by any particular modality (pure aspiration liposuction, ultrasound, or laser). The quality of the result is determined by the skill of the surgeon and the patient’s tissue elasticity, not by the technology.

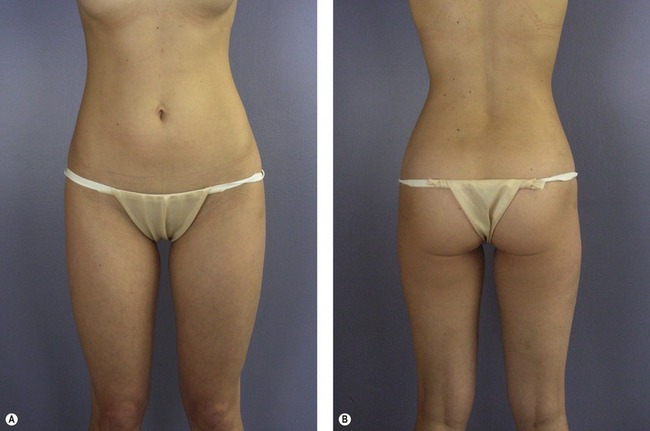

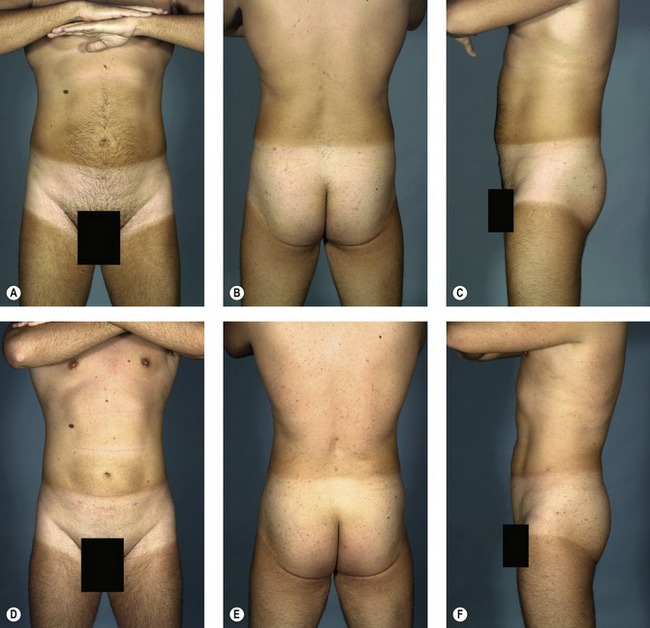

Understanding the applied anatomy of body aesthetics is critical to obtaining satisfying outcomes. There are substantial differences between the sexes. In fit young women (Fig. 59.2), hourglass curves are the rule with balanced proportions between the hips and shoulders. The waist is narrower than the hips. The inner thighs should each have a gentle convex curve and minimal contact with the contralateral thigh. The outer thighs also should have a convex curve that blends smoothly with the buttocks. In fit young men (Fig. 59.3), the optimal waist circumference is also smaller than hip circumference, but the difference is less than in women.

Fig. 59.3 A&B, Desirable proportions in a fit, young male weight lifter. A, On anterior view, rectus abdominis muscles are visible through thin subcutaneous fatty layer. Large muscle attachments at the iliac crest produce a distinct fullness in this area. Waist suppression is present, but less pronounced than in women. B, On posterior view, the relative size of the upper body is larger, due mostly to development of the latissimus dorsi muscles, and the relative size of the pelvis is smaller than in the female. Less fat is present over the hips than in females.

Technical steps

Instrumentation

The essence of liposuction is vacuuming of fat. Liposuction takes advantage of the relative weakness of low density adipose tissue, which, when subjected to a vacuum, is preferentially aspirated while the more resistant supporting fibrous stroma, containing neurovascular bundles, is largely left in situ. This latticework of neurovascular bundles remains to nourish the overlying skin and associated adnexal structures (see Fig. 59.1).

Powered hand pieces

Our preferred modality for lipoplasty is power-assisted liposuction (MicroAire Surgical Instruments, LLC; www.microaire.com), but equivalent results can be achieved with other modalities. Power-assisted liposuction utilizes an electric or gas-driven motor to impart a vibrating motion to the cannula. The cannula tip reciprocates at a rate of 3000 times per minute with an excursion of 2–3 mm (Fig. 59.4). This low energy system is atraumatic and facilitates passage of the cannula through tissues with less force and more precision. Disadvantages of the system include that it is more cumbersome than conventional systems and creates vibrations and noise that may be bothersome.

Cannulas

Multiple cannula tip configurations exist. We use blunt, triple-hole (Mercedes) cannulas in single or double row configurations (Fig. 59.5). We use cannula diameters ranging from 2.4 mm to 5 mm on the torso and extremities. Smaller diameter cannulas are less likely to create contour irregularities, but take longer to remove fat and may result in more tissue trauma. Cannula lengths are generally 15–30 cm. Shorter cannulas offer more control and a faster flow rate. They are also safer for avoiding inadvertent deep penetration in curved areas (i.e., ribs) and for avoiding end hits on the undersurface of the skin. Longer cannulas are preferable in long, straight areas such as the arms or anterior thighs. Because there is less control with the longer cannulas, it is important for the surgeon to either feel or see the cannula tip at all times.

Preoperative marking

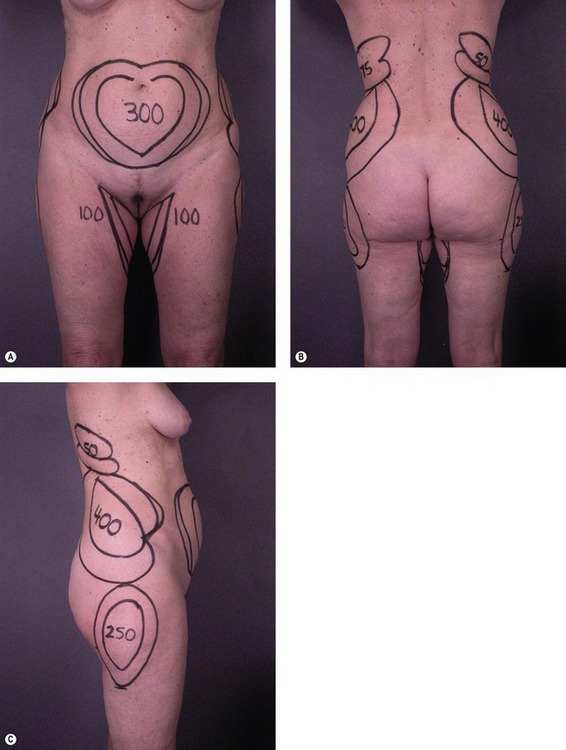

The surgeon should make topographic markings on the patient with permanent markers to delineate the position and extent of fatty bulges (Fig. 59.6). Marking the volume of expected aspirate on the skin is also helpful during surgery. Incision sites should be marked in locations that are inconspicuous; either in natural crease lines, Langer’s lines, or in areas usually covered by minimal garments. To create smoother contours, the incisions are usually made at the border of a treatment area rather than within the area.

Maintenance of normothermia, prevention of deep venous thrombosis

Core temperatures are monitored during the operation and maintained at >36.0°C (96.8°F). The operating room should be warm at the beginning of the case to minimize patient heat loss. Underbody and over body heating blankets (Bair Hugger, www.bairhugger.com) will facilitate maintenance of normal body temperature. Patients at increased risk for deep venous thrombosis are given appropriate prophylaxis.

Prep and drape

Circumferential Prep Method 1 (GHP)

The operating table is draped with sterile sheets before the patient is brought into the operating room. Extra drapes are placed at the foot of the table to wrap the feet. The awake patient stands next to the operating table and is painted circumferentially with povidone-iodine after which the patient is helped to lie on the sterile-draped table. The patient is covered with a sterile sheet, and the feet and lower legs are wrapped in sterile towels. The patient is then induced by the anesthesiologist.

Tumescent infiltration and fluid resuscitation

| Lidocaine 2% | 20 mL |

| Epinephrine 1 : 1000 | 1 mL |

| Lactated Ringer’s solution | 1000 mL |

| Lidocaine 0.04% with epinephrine 1 : 1,000,000 | 1026 mL |

Patient positioning

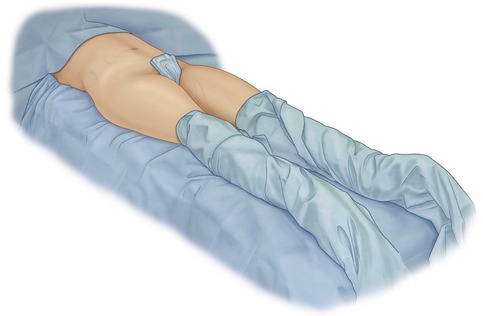

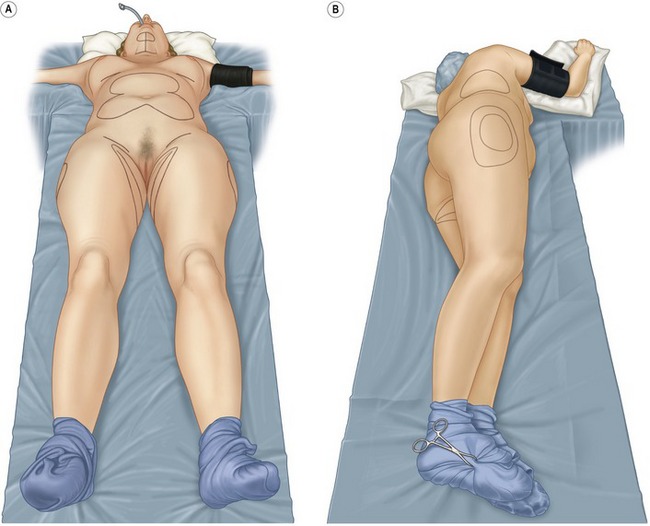

Key goals when planning patient positioning are to have adequate exposure of treatment areas and the ability to assess contours intraoperatively. The senior author (GHP) uses the right and left lateral decubitus and supine positions to provide optimal exposure for all areas. A sterile Mayo stand cover under the patient is used to turn the patient from side to side (Fig. 59.8). The anesthesiologist participates in the turns to avoid injury to the neck or upper extremities. For very large patients, or patients requiring extensive treatment of posterior areas, the patient is more easily treated prone and supine.

The junior author (DAS) uses the following technique. With the patient supine, the hip and knee of the side to be treated are flexed to 90 degrees by the assistant. The assistant then elevates the ipsilateral pelvis off of the table and rotates it approximately 60 degrees, permitting exposure of the flanks and back (Fig. 59.9). Most of the movement occurs at the pelvis and is created by the assistant lifting the hip. Minimal downward pressure is exerted on the knee to avoid stretch injuries to the sciatic nerve or possible injury to the hip joint. For patients with orthopedic injuries, all movements are confirmed to be comfortable for the patient by practicing the positioning while the patient is awake.

Fig. 59.9 Patient supine with pelvis rotated for treatment of flank/hip. If more rotation is required, assistant stands opposite surgeon, places left hand on patient’s right knee, right hand on patient’s mid back, and gently rolls patient’s lower body to expose posterior areas. Anesthesiologist may also place patient’s right arm over chest to avoid traction injury to right brachial plexus.

Cannula placement and movement

Most of the fat should be removed from the deep layer of the superficial fascia. If the surgeon wishes to work in a more superficial plane, only small diameter cannulas should be used. Feathering at the periphery of a treated area also contributes to smoother results. The surgeon should move the cannula with a gentle piston-like motion and remove the cannula from the tissues to change direction. To avoid depressions at the entry incisions, the surgeon should keep the tip of the cannula away from the vicinity of the access incision as much as possible (Fig. 59.10). In convex regions, elevating the handle of the cannula when moving forward keeps the cannula tip in the desired deep plane and avoids end hits in the undersurface of the skin (Fig. 59.11).

Assessment of endpoint

Determining optimal suction volumes in each treatment zone should be done using several techniques simultaneously. The surgeon should have a preliminary volume estimate for each region based on preoperative exam. The calibrated suction system provides quantitative measurements to facilitate aspirate volume control. When about half the volume estimate has been extracted, the surgeon should use visual assessment and pinch test (Fig. 59.12) to judge end point. If the aspirate becomes excessively bloody, the surgeon should move to the next area for treatment. It is wise to be conservative with suction volumes because iatrogenic depressions may be difficult to correct.

Complications

Complications are divided into suboptimal aesthetic results and medical/surgical complications.

Suboptimal aesthetic results

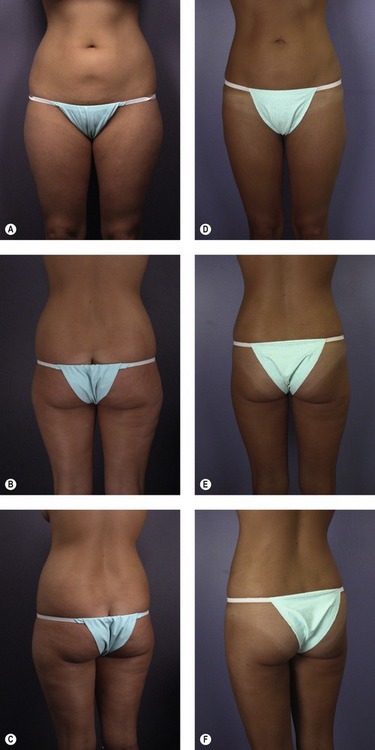

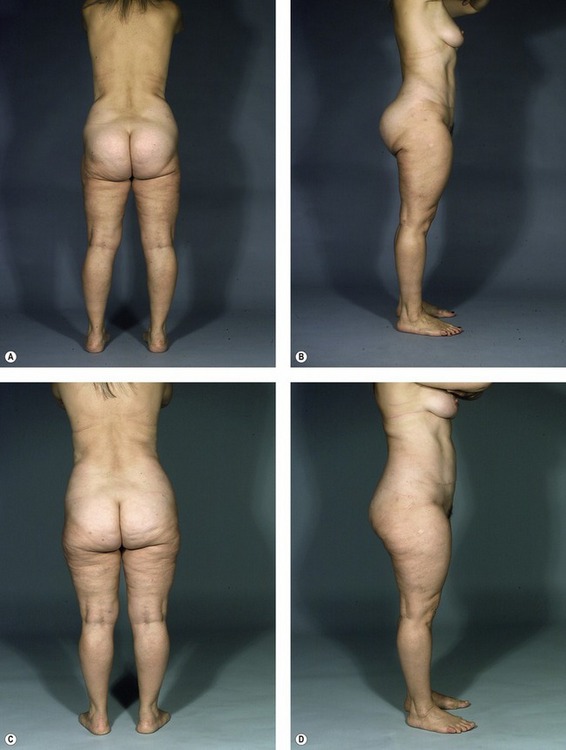

Surface contour irregularities may also result from poor skin elasticity, suctioning in superficial planes, or aggressive fat resection (Fig. 59.13).

Fig. 59.13 A–D, 55-year-old woman who underwent liposuction and was left with depressions in the lateral thighs and buttocks. Shown before (A, B) and after (C, D) liposuction of the upper buttocks, abdomen, and flanks with fat grafts to the lateral thighs, lower lateral buttocks and subgluteal regions bilaterally. A total of 1100 mL of fat was grafted in three stages over three years. She is shown six months after last grafting procedure. Although the buttocks are smaller, they have been elevated by the grafting. The lateral extent of the infragluteal crease has been lessened.

Medical/surgical complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Take preoperative and postoperative pictures with lighting optimized to demonstrate contour irregularities (see Fig. 59.13).

• In larger volume cases, treat the more prominent bulges rather than diffuse areas to have higher impact results with lower overall suction volumes.

• Weigh patients before and after surgery and emphasize to overweight patients that losing weight through diet after surgery leads to more dramatic results.

• Clarify prior to surgery that patients should expect improvement, but not perfection. Many patients may benefit from a second stage liposuction “enhancement”, but it is uncommon for a patient to need a “revision”.

• Offer staged liposuction of selective areas under local in obese patients. Treatment under local is safer for these patients, and improvement in selected areas may be an effective catalyst for them to lose weight.

Pitfalls

• Avoid the unrealistic goal of tightening skin with liposuction (i.e., suction of the abdomen when an abdominoplasty is indicated, or suction of the neck when facelift is indicated).

• Minimize cases of large volume liposuction (>5 liters) to maintain more control over your results.

• Avoid over-resection. It is much easier to take more out later than to put it back through fat grafting.

• Avoid suctioning lower buttocks and upper posterior thighs to prevent creation of a ptotic buttocks.

• Avoid lumpy results by suctioning in deeper subcutaneous planes and using smaller diameter cannulas.

Summary of steps

1. The essence of liposuction is vacuuming of fat. The movements of the cannula avulse the fat, and the aspirator vacuums the tissue into a collection bottle.

2. Preoperative marking. The surgeon should make topographic markings on the patient with permanent markers to delineate the position and extent of fatty bulges.

3. To create smoother contours, the incisions are usually made at the border of a treatment area rather than within the area.

4. Core temperatures are monitored during the operation and maintained at >36.0°C (96.8°F). Patients at increased risk for deep venous thrombosis are given appropriate prophylaxis.

5. Patients can be treated under local or general anesthesia.

6. Prep and drape. For treating multiple areas, both authors use a single, circumferential, povidone-iodine prep for the entire case. Two different circumferential prep methods may be used depending on the surgeon’s preference.

7. The tumescent solution used by the senior author (GHP) for operations under general anesthesia consists of lidocaine, epinephrine and lactated Ringer’s solution, in a recipe containing 400 mg lidocaine in each liter. Most patients do not require supplemental intravenous fluid resuscitation.

8. Key goals when planning patient positioning are to have adequate exposure of treatment areas and the ability to assess contours intraoperatively.

9. Cannula placement and movement: most of the fat should be removed from the deep layer of the superficial fascia.

10. As a general rule, access incisions should be at least 1.5 times longer than the diameter of the cannula.

11. Determining optimal suction volumes in each treatment zone should be done using several techniques simultaneously. The surgeon should have a preliminary volume estimate for each region based on preoperative exam.

12. At the completion of liposuction, the incision sites are sutured with one 5-0 Nylon, and covered with sterile, absorbent cotton. The patient is then placed in a compression garment.

Brown SA, Lipschitz AH, Kenkel JM, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of epinephrine use in liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(3):756–763.

Commons GW, Halperin B, Chang CC. Large-volume liposuction: A review of 631 consecutive cases over 12 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1753–1763.

Grazer FM, de Jong RH. Fatal outcomes from liposuction: Census survey of cosmetic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):436–446.

Iverson RE, Lynch DJ. American Society of Plastic Surgeons Committee on Patient Safety. Practice advisory on liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(5):1478–1490.

Kenkel JM, Lipschitz AH, Shepherd G, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of lidocaine and monoethylglycinexylidide in liposuction: A microdialysis study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(2):516–524.

Klein JA. Tumescent technique for local anesthesia improves safety in large volume liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1085.

Pitman GH. Liposuction and aesthetic surgery. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 1993.

Pitman GH. Liposuction in the outpatient setting. Aesthet Surg J. 1999;19(2):167.

Pitman GH. Discussion. Large volume liposuction: A review of 631 consecutive cases over 12 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1764–1765.

Rohrich RJ, Leedy JE, Swamy R, Brown SA, Coleman J. Fluid resuscitation in liposuction: A retrospective review of 89 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):431–435.

Stevens WG, Cohen R, Vath SD, Stoker DA, Hirsch EM. Does lipoplasty really add morbidity to abdominoplasty? Revisiting the controversy with a series of 406 cases. Aesthet Surg J. 2005;25:353–358.