10 Pulmonary Vasculitis and Pulmonary Hemorrhage

Pulmonary vasculitis

Overview of Pulmonary Vasculitis

Inflammation of arteries and veins can occur in many inflammatory lung diseases, including infections. By convention, the diagnostic term pulmonary vasculitis is restricted to a relatively limited number of diseases in which vascular inflammation is thought to be a major component of the pathologic process. Most pulmonary vasculitides are believed to be immune-mediated diseases, although their etiology and pathogenesis remain unknown. By best estimates, the overall annual incidence of the major forms of vasculitis is 39 per 1 million.1

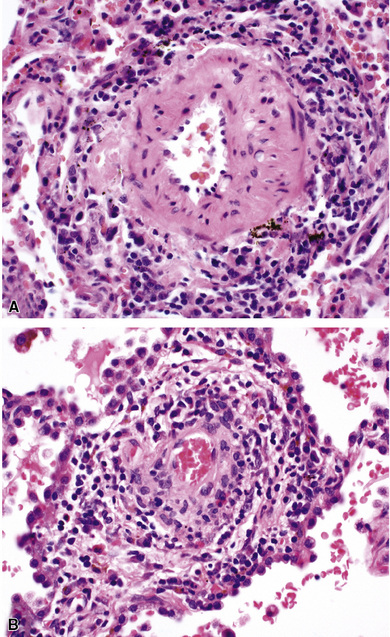

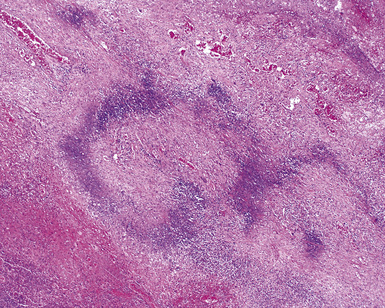

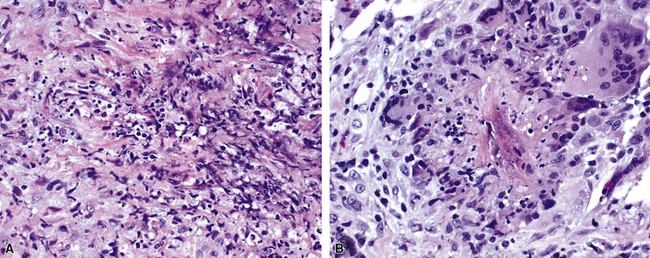

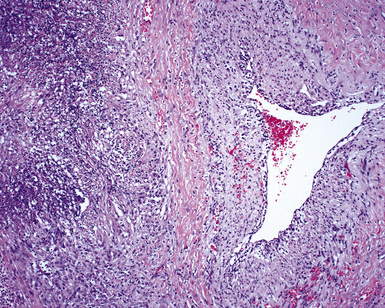

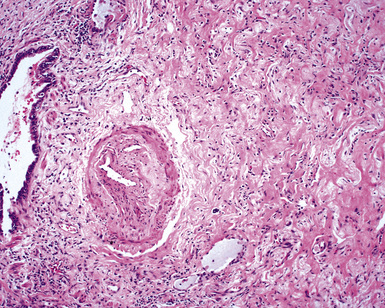

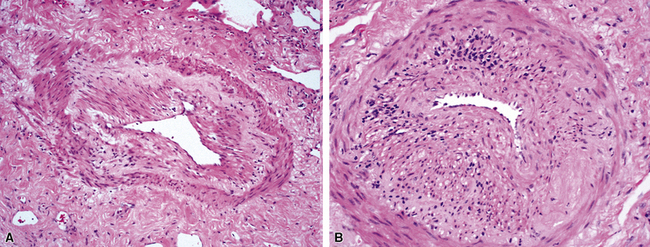

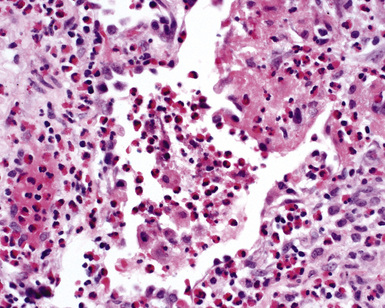

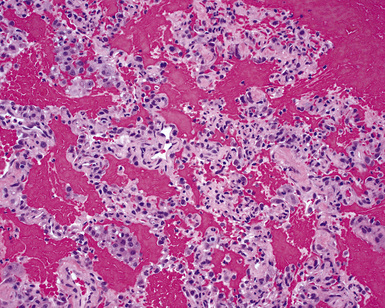

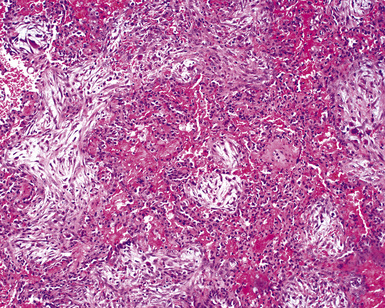

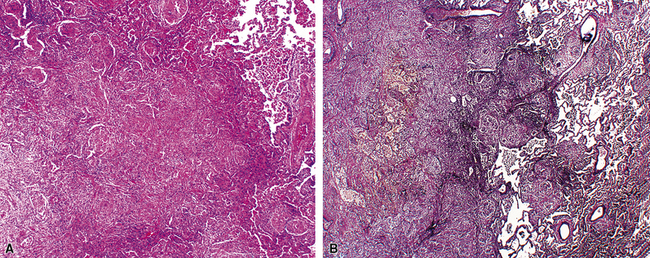

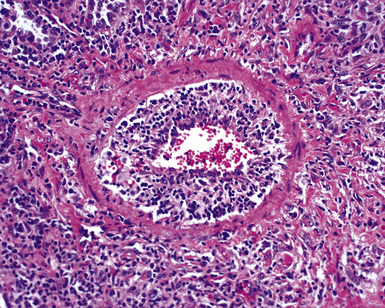

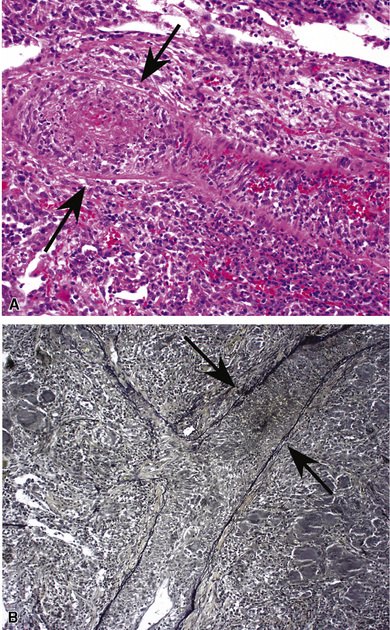

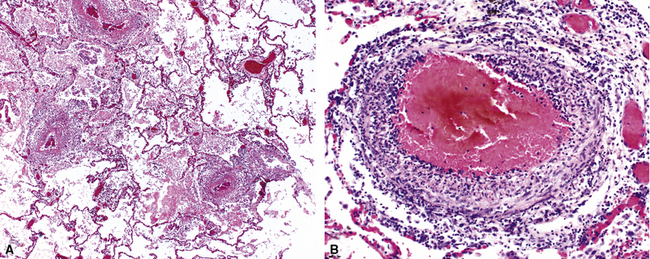

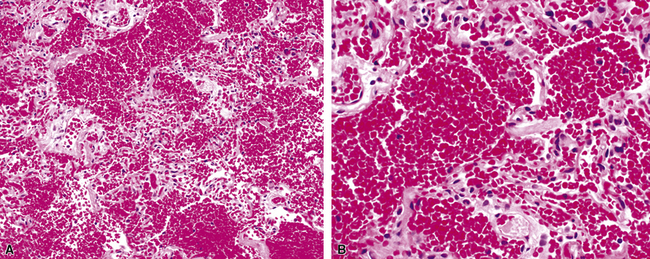

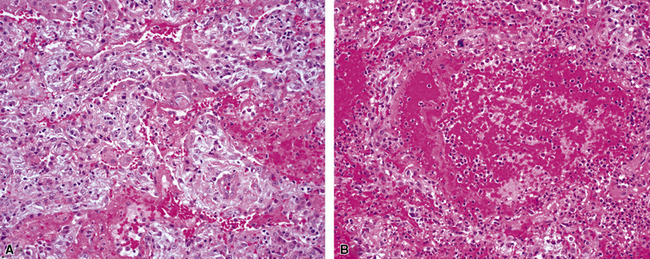

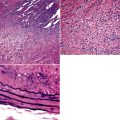

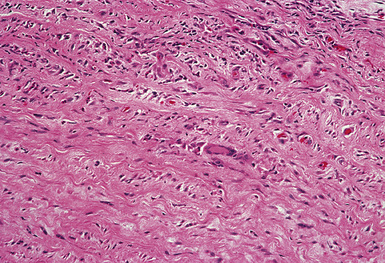

When pulmonary vasculitis occurs, there is inflammation of the vessel wall, often accompanied by fibrin and sometimes, necrosis. Cuffing of blood vessels by inflammatory cells, a nonspecific finding, must be distinguished from infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media and intima of arteries and veins (Fig. 10-1).

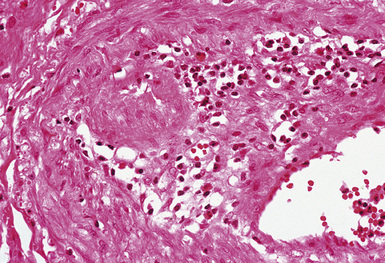

A diagnosis of pulmonary vasculitis carries a strong implication for immediate therapeutic intervention (typically immunosuppression) and therefore should never be made lightly. Furthermore, serologic and clinical correlation with the pathologic findings is essential for a correct diagnosis. Typical histologic examples of pulmonary vasculitis-capillaritis are shown in Figure 10-2.

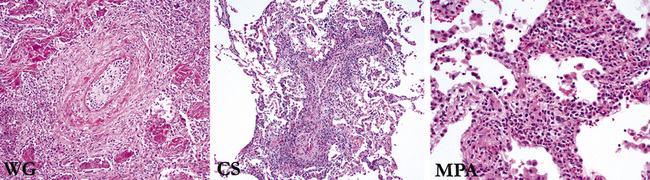

The general category of pulmonary vasculitis includes a number of different diseases that can be more easily understood by dividing them into three main groups: (1) idiopathic vasculitic syndromes that commonly involve the lung (e.g., Wegener granulomatosis [WG]), (2) vasculitic disorders that rarely involve the lung (a much larger number), and (3) miscellaneous conditions that produce pulmonary vascular inflammation2,3 (Box 10-1).

Box 10-1 Pulmonary Vasculitis Syndromes

Modified from Travis W, Koss M. Vasculitis. In: Dail D, Hammar S, eds. Pulmonary Pathology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994:1027–1095.

WG, Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS), and microscopic polyangiitis are the idiopathic vasculitis syndromes that commonly affect the lung. The conditions of bronchocentric granulomatosis and lymphomatoid granulomatosis traditionally have been grouped in the category of pulmonary “angiitis and granulomatosis”; however, neither of these entities is currently thought to be a vasculitic condition. Bronchocentric granulomatosis is a morphologic pattern of airway inflammation that occurs in a variety of conditions, especially infection, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis (also known as angiocentric immunoproliferative disorder) is now known to represent a lymphoproliferative disease in which prominent vascular involvement occurs.4–6

Idiopathic Vasculitic Syndromes That Commonly Affect the Lung

Wegener Granulomatosis

WG is a rare systemic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that has vasculitis as a major histologic manifestation. WG predominantly affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys.7 Although this pattern of involvement is often referred to as the “classic triad” of WG, more frequently only one or two sites may be involved. In one series reported by DeRemee and associates, involvement of all three sites was seen in only 14 of 50 patients.8 “Limited WG” historically has been defined as disease involving the lungs without associated glomerular disease,9 although the term is also used to describe active disease without involvement that threatens the function of a vital organ or the patient’s life.10

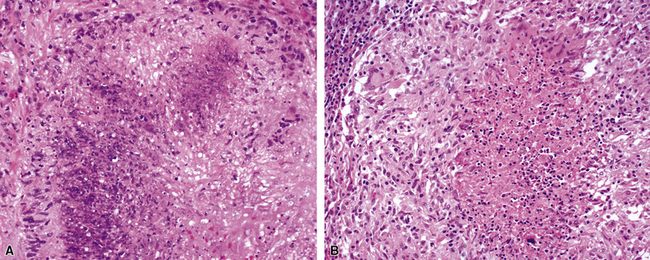

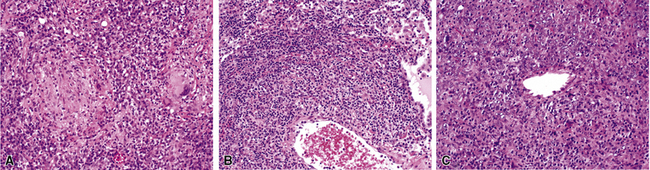

Despite the designation granulomatosis, well-defined granulomas without necrosis (sarcoid-like) are not a feature of this disease. The necrotizing lesions of WG have a peripheral zone of palisaded histiocytes, contrasting with the more epithelioid histiocytes seen at the periphery of necrosis produced by mycobacteria or fungi (Fig. 10-3). In fact, when well-formed (sarcoid-like) granulomas without necrosis are present in a potential case of WG, another diagnosis should be considered (usually infection).

Clinical Features

WG affects about 1 in every 3 million people in the United States11 and 1 in 8.5 million people in the United Kingdom.12 There is debate as to whether WG occurs more frequently during cold seasons, with some studies suggesting an increased occurrence in winter months.12 Other studies have disputed these results.11 Although the etiology of WG remains essentially unknown, several theories have been proposed. One theory is that an inciting inflammatory event invokes a specific immune response leading to the production of ANCAs (also discussed in the “Laboratory Studies” section), with ANCA playing a direct role in inciting tissue damage.13,14 A potential link between infections and the development of WG is being explored. It has been noted that a subtype of ANCA directed against lysosomal membrane–associated protein 2 (LAMP-2) is found in more than 90% of patients with pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis and frequently coexists with antiproteinase-3, and antimyeloperoxidase LAMP-2 has been observed to activate neutrophils, as well as causing injury to vascular endothelial cells in the absence of neutrophils. LAMP-2 cross-reacts with the bacterial adhesin FimH, and one study found that infection with bacteria expressing FimH occurred in 69% of patients in whom ANCA-positive glomerulonephritis subsequently developed.15,16 Although such findings suggest a potential link between infection and the production of ANCA, further study is needed in regard to a link between infection and WG. Similarly, other studies have demonstrated a link between T cells and the development of ANCA and have shown a particular role for T-helper 1 (Th1) lymphocytes, although the role of the Th1 lymphocytic pathway in the development of WG is still being elucidated.17,18 Genetic factors, toxic exposures, and deficient proteinase-3 clearance are also being explored as potential causes and contributing factors.11,19

WG occurs at any age but typically is a disease of adults, with a mean age of 50 years.20–22 A list of the clinical manifestations of WG is presented in Table 10-1. Body sites most commonly affected are the head and neck region, followed by the lung, kidney, and eye.20,23 Patients may experience a number of other complaints such as hoarseness, stridor, earache, hearing loss, otorrhea, cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, or pleuritic pain. Pulmonary symptoms in the absence of upper respiratory tract manifestations are unusual. Destructive inflammation of the nose may result in a saddlenose deformity. In addition, patients may exhibit more generalized systemic signs and symptoms including arthralgias, fever, cutaneous lesions, weight loss, and peripheral neuropathy.24 Rarely WG may involve the salivary glands, pancreas, breast, mediastinum, gastrointestinal tract, prostate and urethra, vagina and cervix, heart, spleen, or peripheral or central nervous system.2,25–27

| Manifestation | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| At Presentation | During Course of Disease | |

| Head and neck manifestations | 73 | 92 |

| Sinusitis | 51 | 85 |

| Nasal disease | 36 | 68 |

| Otitis media | 25 | 44 |

| Hearing loss | 14 | 42 |

| Subglottic stenosis | 8 | 16 |

| Ear pain | 1 | 14 |

| Oral lesions | 3 | 10 |

| Pulmonary manifestations | 45 | 85 |

| Infiltrates | 23 | 66 |

| Nodule | 22 | 59 |

| Cough | 19 | 46 |

| Hemoptysis | 12 | 30 |

| Pleuritis | 10 | 28 |

| Renal manifestations | 18 | 77 |

| Eye manifestations | 15 | 52 |

| Conjunctivitis | 5 | 18 |

| Dacryocystitis | 1 | 18 |

| Scleritis | 6 | 16 |

| Proptosis | 2 | 15 |

| Eye pain | 3 | 11 |

| Visual loss | 0 | 8 |

| Retinal lesions | 0 | 4 |

| Corneal ulcers | 0 | 1 |

| Iritis | 0 | 2 |

| Systemic manifestations | ||

| Joints | 32 | 67 |

| Fever | 23 | 50 |

| Skin changes | 13 | 46 |

| Weight loss | 15 | 35 |

| Peripheral nervous system abnormalities | 1 | 15 |

| Central nervous system abnormalities | 1 | 8 |

| Pericarditis | 2 | 6 |

Data from Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488–498.

Laboratory Studies

Nonspecific abnormalities on general laboratory tests are often present in patients with WG. The most common of these include leukocytosis, thrombocytosis (>400,000 cells/μL), marked elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and normochromic normocytic anemia. In the past decade, the diagnosis of WG has been dramatically aided by the discovery and use of serum ANCA.28–32

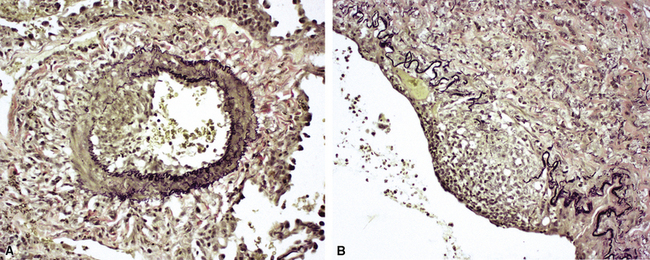

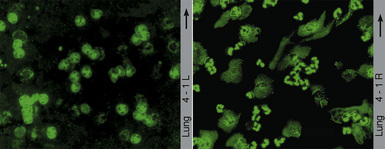

Two major immunofluorescence patterns occur as expressions of ANCA (Fig. 10-4): the cytoplasmic or classic type (c-ANCA) and the perinuclear type (p-ANCA).33 The c-ANCA pattern is associated with WG and is present in the vast majority of patients with active generalized disease. Partial or complete remission of disease is reflected in a lower frequency of a positive test result, but 30% to 40% of patients in complete remission still have identifiable antibodies.34 The p-ANCA pattern can be seen in a small percentage of patients with WG, but it is more characteristic of idiopathic necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis, microscopic polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, and CSS.35

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-1.)

The ANCA immunofluorescence patterns have been shown to correspond to specific antigen immunoreactivities; c-ANCA typically has specificity for proteinase-3, while most p-ANCAs have a specificity for myeloperoxidase. Studies have shown no significant difference in the lung biopsy findings from WG patients with c-ANCAs versus those with p-ANCAs.36,37 Levels of c-ANCA in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid have not been shown to be a more specific predictor of WG or of the level of disease.38 Importantly, the presence or absence of a positive serum test for c-ANCA alone is not sufficiently specific to make or exclude the diagnosis of WG, and c-ANCA may occasionally be encountered in patients with other vasculitic syndromes or infection.39

Radiologic Features

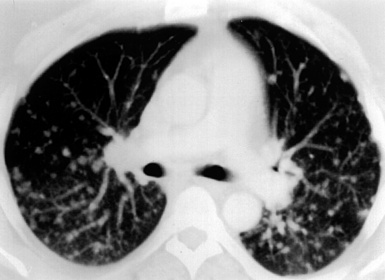

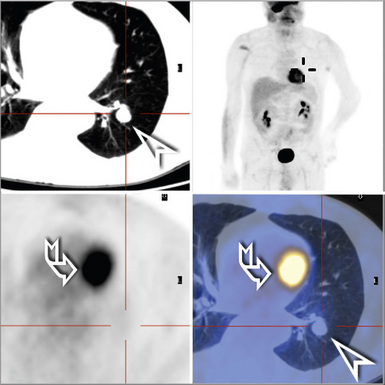

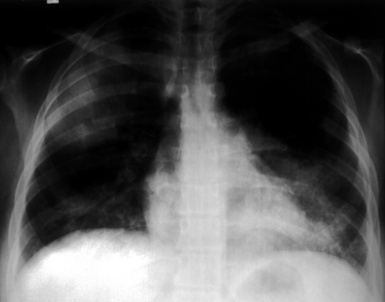

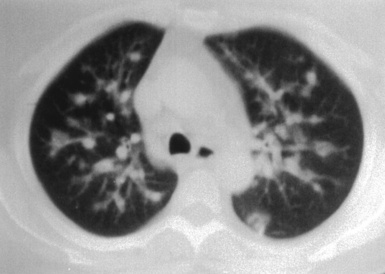

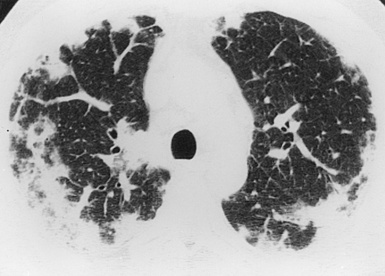

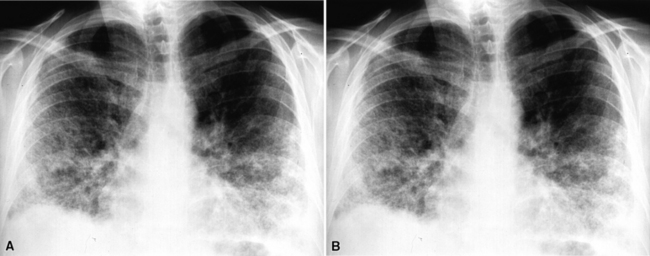

Most patients with pulmonary disease have multiple opacities (Figs. 10-5 and 10-6) in the form of well-marginated nodules or masses of variable size (0.5–10 cm). Lesions may wax and wane over time. Most occur in the lower lobes.40–42 Poorly defined or even spiculated nodules may also be seen.43 Cavitation of nodules occurs in 25% to 50% of cases, with cavity walls typically being thick and irregular. Such lesions may evolve into thin-walled cysts or disappear completely with therapy.42,44 WG is often included in the differential diagnosis for interstitial lung disease because multifocal, ill-defined parenchymal consolidations can occur (with or without cavitation) and diffuse reticular and nodular interstitial opacities have also been reported.42,45

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-2.)

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-3.)

Patients with WG may present initially with pulmonary hemorrhage. In this setting, diffuse infiltrates on chest radiographs and diffuse air space opacities on computed tomograms are observed (see Fig. 10-6). In children, pulmonary hemorrhage is a common presentation of WG, while pulmonary nodules occur less frequently in pediatric patients.22

Pleural effusion accompanies WG in 20% to 50% of cases, sometimes with focal pleural thickening. Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is an unusual finding in WG and, when significant, should raise concern for an alternate diagnosis. On rare occasions, WG occurs as a solitary pulmonary nodule (with or without cavitation), or as an isolated area of consolidation.46

Computed tomography (CT) provides optimal visualization of the number, location, and morphologic characteristics of the pulmonary abnormalities in WG. Well-marginated nodules and masses, sometimes with spiculated borders, are typical findings. A “feeding” vessel is seen in 88% of nodules (see Fig. 10-6), consistent with the angiocentric nature of this disorder.47 Cavitation is identified in 50% of cases. Another very common finding in WG is wedge-shaped peripheral opacities mimicking the CT appearance of infarct. Other, less common radiologic presentations include air bronchograms and the CT halo sign (ground glass opacity surrounding a pulmonary nodule or mass).47,48 Stenosis of the trachea or large airways may occur in short or long segments and may be complicated by partial or complete lobar collapse.45,49,50

Pathologic Features

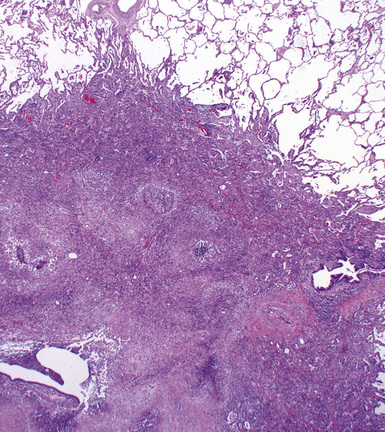

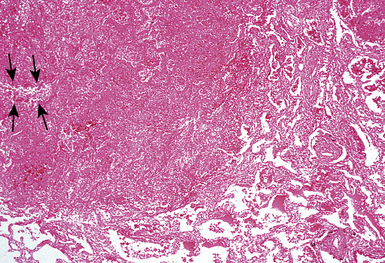

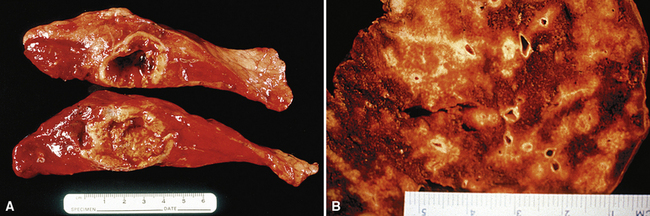

WG is characterized by the presence of multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules, often with cavitation51 (Fig. 10-7; see also Fig. 10-6). Solid nodular zones of consolidation with areas of punctate or geographic necrosis are typical findings (Figs. 10-8 and 10-9). WG can rarely present with a solitary lung lesion, but solitary granulomatous disease is more likely to be of infectious origin.52 When dealing with a solitary granulomatous lung nodule, a combination of both the classical histology and typical clinical or serologic findings of WG should be present before making a diagnosis.46 Even when special stains for organisms and cultures are negative, most of these solitary lesions represent old fungal or mycobacterial infection. Rarely the lesions of WG may predominantly involve bronchi. When acute lung hemorrhage is prominent, the cut surface of the lung is bloody and dark red.

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-5.)

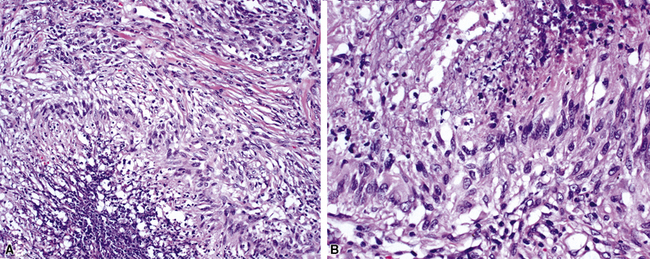

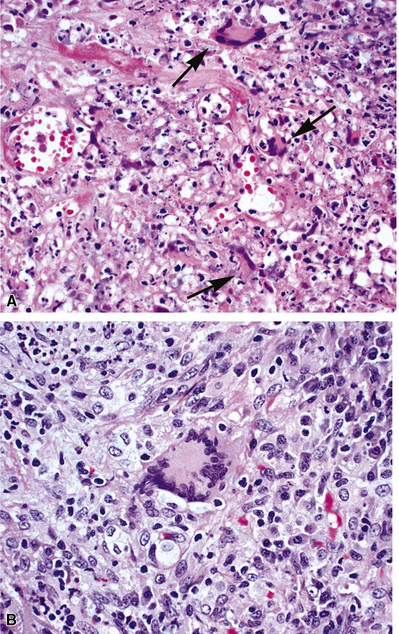

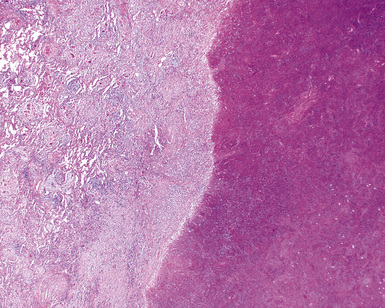

At scanning magnification, the pulmonary lesions of WG simulate their radiologic appearance (see Fig. 10-8). The classic findings consist of nodular areas of consolidation with variable zones of necrosis. Major diagnostic criteria, presented in Box 10-2, include parenchymal necrosis (see Fig. 10-9), vasculitis (Fig. 10-10), and granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 10-11). Another important feature is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, giant cells, and eosinophils (Fig. 10-12). Parenchymal necrosis can take the form of neutrophilic microabscesses (Fig. 10-13) or large zones of geographic necrosis (see Fig. 10-9). The neutrophilic microabscesses are nearly pathognomonic of the disease and can be found within the mixed inflammatory infiltrate or within fibrous connective tissue including the adventitial collagen of larger arteries and veins and the pleura. Early microabscesses may consist of a small collection of neutrophils surrounding a focus of degenerated, often hypereosinophilic, collagen.51

Box 10-2 Wegener Granulomatosis: Major Histopathologic Manifestations (Diagnostic Criteria)

Data from Travis W, Koss M. Vasculitis. In: Dail D, Hammar S, eds. Pulmonary Pathology. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994:1027–1095; and Travis WD, Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Surgical pathology of the lung in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Review of 87 open lung biopsies from 67 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:315–333.

As illustrated in Figure 10-9, the classic geographic necrosis of WG is typically basophilic, owing to the presence of numerous necrotic neutrophils. The necrotic centers of WG lesions often lack the “ghosted” image of lung structure, a diagnostic clue useful in the case with atypical features (Fig. 10-14). This likely occurs because the necrotic zones of WG generally are not the result of “infarct-like” zonal parenchymal necrosis but rather occur by progressive expansion of collagen necrosis.

The “granulomatous” inflammation of WG typically includes giant cells scattered randomly or in loose aggregates.10–15 Also commonly observed are palisaded histiocytes (Fig. 10-15), giant cells lining the border of geographic necrosis or microabscesses, and microgranulomas consisting of small foci of palisaded histiocytes arranged in acartwheel pattern around a central nidus of necrosis51 (Fig. 10-16). The presence of tightly cohesive, sarcoid-like granulomas is very rare in WG and suggests infection or necrotizing sarcoid. Also, the presence of granulomas without associated necrosis favors an infectious etiology over WG.

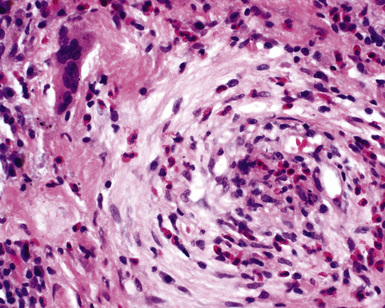

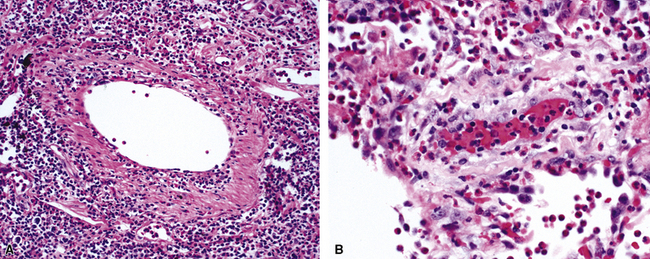

The vasculitis of WG typically affects small arteries and veins up to 5 mm in diameter. When vasculitis is seen in the surgical biopsy, it most often occurs within the dense inflammatory infiltrate surrounding nodular or geographic areas of necrosis (Fig. 10-17). Vasculitis in WG may comprise a variety of inflammatory cells including acute or chronic mural inflammation, necrotizing stellate granulomas, non-necrotizing stellate granulomas, and giant cells.51 Cicatricial changes consisting of mural fibrosis or luminal obliteration may be seen in specimens following therapy. Destruction of the vascular elastic laminae is commonly observed (Fig. 10-18). Sometimes the inflammation is limited to the endothelium (endotheliolitis) and subendothelial aspect of the vessel wall. Despite these potential vascular changes, if necrotizing vasculitis is held as a requirement for the diagnosis, many cases of WG will be missed.

Another distinctive vascular manifestation of WG is capillaritis (Fig. 10-19). In many cases, capillaritis is only focally evident in the biopsy.51 When capillaritis is prominent, it is distinctive and easily recognized. In the rare case of WG dominated by capillaritis, a careful search throughout the rest of the biopsy should be made for more typical findings of WG such as granulomas, foci of necrosis (such as neutrophilic microabscesses), multinucleate giant cells, and vasculitis affecting arterioles or veins.

In addition to these major histologic features, a variety of minor histologic features may be encountered (Box 10-3), including alveolar hemorrhage, interstitial fibrosis, lipoid pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, lymphoid hyperplasia, extravascular tissue eosinophils, and xanthomatous lesions. WG can also involve the airways, causing chronic bronchiolitis, acute bronchiolitis or bronchopneumonia, the histologic pattern of organizing pneumonia (see further on), bronchocentric granulomatosis, follicular bronchiolitis, and bronchial stenosis.51,53 Occasionally one of these minor lesions may be the dominant lung biopsy finding.51 Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage is a severe life-threatening manifestation of WG. The pattern of bronchocentric granulomatosis is another rare manifestation of WG encountered in 1% of cases.51,53 Organizing pneumonia (Fig. 10-20) can be seen in 70% of lung biopsies from patients with WG51; rarely, it may be sufficiently dominant that some have referred to this manifestation as the “bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia” (BOOP) variant of WG.51,54 This should not be confused with the idiopathic entity of BOOP (cryptogenic organizing pneumonia) but should be recognized as nonspecific secondary organization following alveolar injury related to the underlying lesions of WG.

Box 10-3 Wegener Granulomatosis: Minor Histopathologic Manifestations*

Data from Rose A, Sinclair-Smith C. Takayasu’s arteritis. A study of 16 autopsy cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1980;104:231–237; and Jakob H, Volb R, Stangl G, et al. Surgical correction of a severely obstructed pulmonary artery bifurcation in Takayasu’s arteritis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4:456–458.

The lung biopsy findings from patients with WG may not show classical histologic findings, especially if patients are either biopsied very early in the course of disease or following therapy.51,55 Interstitial fibrosis (sometimes with scattered giant cells, but without necrosis)(Fig. 10-21), bronchial or bronchiolar scarring, and cicatricial vascular changes (Fig. 10-22) are common in lung biopsies from patients who have received therapy.51,55 Wedge biopsies provide the best results for an accurate diagnosis of WG. Transbronchial biopsies rarely yield diagnostic information, although in the appropriate clinical context the presence of a few neutrophil microabscesses, giant cells, or capillaritis may be helpful in supporting the diagnosis. Transthoracic needle core biopsies may occasionally show features suggesting a diagnosis of WG.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for WG based on lung biopsy tissue depends somewhat on the constellation of changes present and includes granulomatous infection,52 lymphomatoid granulomatosis,56,57 CSS,58–61 sarcoidosis, necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis,56,62,63 rheumatoid nodules,63 bronchocentric granulomatosis,53,63,64 and diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage syndromes.65,66

Occasionally, a form of diffuse large B cell malignant lymphoma commonly referred to as lymphomatoid granulomatosis (see Chapter 15) can bear a striking resemblance to WG6 (Fig. 10-23). Like classic WG, this neoplastic process is characterized pathologically by the presence of multiple necrotic pulmonary nodules. In addition to major clinical differences between these diseases, important histopathologic differences become evident at closer inspection. First, the necrotic areas in lymphomatoid granulomatosis typically demonstrate pale shadows of large necrotic cells (dead lymphoma cells). Second, within the necrotic zones, and at the periphery of necrosis, medium-sized blood vessels can be seen whose outline is expanded by an angiocentric infiltration of lymphoid cells. As noted, this is a diffuse large B cell lymphoma in which the atypical B lymphoid cells are infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and associated with a T lymphocyte–rich inflammatory reaction and vasculitis. In high-grade disease, the vasocentric infiltrate is composed mainly of large atypical B cells. In lower-grade forms, the infiltrate may be polymorphous with more prominent T cells and a mixture of plasma cells, and eosinophils. Immunohistochemistry for CD20 and CD3 highlights the large malignant B cells and background of inflammatory T cells. Immunohistochemistry for EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1) and in situ hybridization studies for EBV are valuable diagnostic tools in this setting. Third, lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a vasodestructive lymphoid neoplasm, so necrosis and obliteration of vessels are common. WG may show necrosis in vascular adventitia, but wholesale medial necrosis in arteries and veins is unusual. Fourth, the atypical cells of lymphomatoid granulomatosis often contain EBV,4,67 a finding not expected in WG. Finally, granulomatous inflammation is comparatively rare in lymphomatoid granulomatosis, so the presence of granulomas in nodular lung lesions should suggest a diagnosis other than lymphomatoid granulomatosis (e.g., infection or WG).

Prominent tissue eosinophilia occurs in approximately 5% of cases of WG (Fig. 10-24). With this finding, the differential diagnosis should include CSS (see later), along with fungal or parasitic infection.58,61,68,69 Peripheral blood eosinophilia is characteristic of CSS and is uncommon in WG.70 Also, asthma is not a characteristic feature of WG, although rarely, asthmatic individuals may develop WG, presumably at a rate similar to that seen in the general population. The distinction between WG and CSS is usually straightforward, but some cases may require careful assessment of all of the clinical, pathologic, and laboratory data (Table 10-2).

Table 10-2 Wegener Granulomatosis versus Churg-Strauss Syndrome: Distinguishing Features

| Clinical/Pathologic Feature | Wegener Granulomatosis | Churg-Strauss Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Rare | Characteristic (diagnostic criterion) |

| Eosinophilia | ||

| Peripheral | Up to 12% | Characteristic* |

| Tissue | Up to 6% | Characteristic* |

| Sinus disease | Destructive, often causing saddlenose deformity | Less severe, usually allergic rhinitis |

| Renal disease | More severe | Usually mild |

| Cardiac disease | Rare | Common |

| ANCA | Usually c-ANCA | Usually p-ANCA |

ANCA (c-ANCA, p-ANCA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (cytoplasmic, perinuclear).

* Eosinophilia may be fleeting and may be difficult to demonstrate during steroid therapy.

Perhaps the most important, and often problematic, consideration in the diagnosis of WG is the exclusion of infection. Mycobacteria and fungi can cause necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis resembling that seen in WG. Solitary necrotizing granulomas can be associated with vasculitis in 87% of mycobacterial lung infections and 57% of fungal lung infections.52 Also, neutrophilic microabscesses are a feature of certain infections, such as blastomycosis and nocardiosis.

A number of important clues can be helpful in the approach to this differential diagnosis, even before special stains for organisms or culture data (which should be routinely ordered in such cases) are available. First, if the lesion is solitary, a high index of suspicion for infection is appropriate.46 Second, WG does not tend to make granulomas without central necrosis,51 except in the rare occurrence of infection superimposed on the necrotic center of a WG lesion. Third, the necrosis of infection may show the “ghosted” outlines of underlying lung parenchyma, a finding uncharacteristic of WG. Fourth, the patient with infection, in whom a bilateral multiple-nodular appearance on radiologic studies may simulate that in WG, is typically quite ill, with generalized systemic symptoms. By contrast, the patient with WG may be relatively asymptomatic, despite numerous necrotic nodules in the lung. Finally, when strictly morphologic assessment fails to clarify the diagnosis, inquiry regarding the presence of sinonasal disease or renal disease and serologic data (c-ANCA and p-ANCA) will usually resolve the quandary.

When WG presents with a predominantly bronchocentric pattern of lung involvement, bronchocentric granulomatosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis.51,53 Patients with bronchocentric WG should demonstrate other distinguishing features of WG, including renal or sinus involvement and a positive ANCA serology.

Diagnosis

The histologic features of WG can be very suggestive of the diagnosis, but as a general rule, it is extremely important to correlate the histopathology with clinical and serologic findings before making a definitive diagnosis on a lung biopsy specimen. The diagnosis can be impossible to make in cases in which only partial clinical or pathologic criteria are present. In these situations a purely descriptive diagnosis with a differential diagnosis may be necessary. As mentioned earlier, ANCA serology can be helpful, as long as one keeps in mind that ANCAs are not specific for WG.71 Moreover, when all other clinical and histopathologic findings are compelling for WG, the diagnosis is still possible despite negative ANCA studies.39

Treatment and Prognosis

WG is commonly a fatal disease if left untreated, with up to 90% of patients dying within 2 years of diagnosis, most often from respiratory or renal failure. Fortunately, therapy with cyclophosphamide and prednisone is very effective in achieving remissions, with 85% to 90% of patients responding to therapy and approximately 75% experiencing complete remission.72 The median time to remission is 12 months, although occasional patients require treatment for more than 2 years before all symptoms resolve. Even in those patients who initially respond to therapy, relapses are common, with up to 50 of initial responders experiencing at least one relapse requiring another course of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pulse cyclophosphamide, and methotrexate are also used to treat WG.20,73–75 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole may reduce relapses for those patients who are in remission.76 The mechanism of this protective action is unknown. Rituximab has more recently shown promise in treatment of WG, particularly limited disease refractory to standard therapy.77 Initial trials of antagonists of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) showed some benefit, but formal trials did not support the initial findings; thus, further study is needed to determine the efficacy of this potential therapy.78 The outcome with WG seems to be significantly worse for patients older than 60 years of age than for younger patients, despite similar clinical manifestations and treatment regimen. Lung function frequently improves after treatment, but in some patients the diffusing capacity may never return to normal.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

CSS is a multisystem disorder characterized by the triad of asthma, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and vasculitis.58,59,61,68–70,79–81 Although CSS was initially described by Churg and Strauss based on a series of autopsy cases,58 it is now recognized primarily as a clinical entity. Accordingly, most cases today are diagnosed on the basis of clinical findings rather than lung biopsy.61

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) proposed two approaches to the diagnosis of CSS (Table 10-3): a traditional format classification and a classification tree.82,83 According to the traditional format classification, six criteria are identified: (1) asthma, (2) eosinophils greater than 10% of the white blood cell differential count, (3) mononeuropathy (including multiplex) or polyneuropathy, (4) non-fixed radiographic pulmonary infiltrates, (5) paranasal sinus abnormalities, and (6) a biopsy containing a blood vessel with extravascular eosinophils.82 If four of six of these criteria are met, the diagnosis can be established with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.7%.82 The ACR criteria for CSS have been retained in the subsequent 1994 Chapel Hill consensus conference criteria and the more recently proposed Watts criteria.84

| Manifestation | Frequency (% of Patients Affected) |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary infiltrates | 72 |

| Mononeuritis multiplex | 66 |

| Abdominal pain | 59 |

| Arthritis/arthralgias | 51 |

| Mild/moderate renal disease | 49 |

| Purpura | 48 |

| Cardiac failure | 47 |

| Myalgia | 41 |

| Löffler syndrome | 40 |

| Erythema/urticaria | 35 |

| Diarrhea | 33 |

| Pericarditis | 32 |

| Skin nodules | 30 |

| Pleural effusion | 29 |

| Hypertension | 29 |

| Central nervous system abnormalities | 27 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 18 |

| Renal failure | 9 |

Modified from Lanham J, Churg J. Churg-Strauss syndrome. In: Churg A, Churg J, eds. Systemic Vasculitides. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1991:101–120.

The major criteria used in the classification tree are asthma, eosinophilia with greater than 10% eosinophils, and a history of allergy.82 According to this method, patients with well-documented systemic vasculitis, but lacking a history of asthma, can be diagnosed with CSS if they have peripheral blood eosinophilia (>10% eosinophils) and a history of allergy other than drug sensitivity.82 This seems appropriate, since patients without asthma, but with a history of allergic disease, can develop CSS.85–87 Both classification methods appear to be useful in the diagnosis, with greater sensitivity provided by the classification tree and greater specificity by the traditional approach.82

Clinical Features

Despite more than 40 years of study, the incidence and epidemiology of CSS remain unclear. Based on available (although limited) population-based studies, CSS is second only to WG as a major cause of systemic vasculitis, and CSS is the diagnosis in approximately 10% of patients who develop a major vasculitic syndrome.1 The exact etiology of CSS is unknown, but an autoimmune etiology is most likely.

CSS affects both sexes equally. The mean age at diagnosis is 50 years, but the systemic vasculitic phase is frequently evident in patients in their late 30s. CSS mainly involves the upper respiratory tract, lungs, skin, and peripheral nerves.59,61,69 Involvement of the heart and kidney also occurs and may be associated with a worse outcome.

CSS often progresses through three distinct phases. In the early or prodrome phase, the disease manifests as allergic rhinitis, asthma, peripheral eosinophilia, and/or eosinophilic infiltrative disease.59,61,69,70 Recurrent episodes of asthma may develop over a period of years before the onset of vasculitis and some data suggest that the interval between the onset of asthma and the subsequent vasculitis phase of the disease has a direct association with prognosis.58,59,61 In the prodrome phase, tissue infiltration by eosinophils can affect the lungs or the gastrointestinal tract. Pulmonary manifestations may take the form of Löffler syndrome, with fleeting pulmonary infiltrates or even chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.

The prodrome is followed by the vasculitis phase. During this phase, patients develop systemic signs and symptoms of vasculitis, such as mononeuritis multiplex and cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Results of p-ANCA assay are usually positive. The ACR criteria necessary for diagnosis are present only during this phase.69 Unfortunately, most of the permanent damage is done by the disease during this phase. For this reason, when eosinophilic pneumonia occurs in an asthmatic patient, CSS should always be raised as a possibility in the differential diagnosis, especially when prominent eosinophilic vasculitis is present in the lung biopsy.

The vasculitis phase is followed by a postvasculitis phase. Here, patients may experience neuropathy and hypertension, typically with persistent asthma and allergic rhinitis.69,88 Proteinuria and gastrointestinal involvement are poor prognostic indicators.89

A major difference between CSS and WG is the frequency of cardiac and renal involvement. Although the heart may be involved in both disorders, up to 47% of CSS patients develop cardiac disease.61,69 CSS can cause cardiac failure, pericarditis, hypertension, and acute myocardial infarction.58,59,61 Also, while renal disease is characteristic in WG, it is less frequent and less severe in patients with CSS.59,61,90

Peripheral neuropathy, often in the form of mononeuritis multiplex, is seen in approximately two thirds of patients with CSS. The most common cutaneous manifestation is leukocytoclastic vasculitis.91 Sinonasal manifestations include nasal obstruction, nasal polyps, rhinnorhea, and thick intranasal crusts.92 Central nervous system involvement can occur in 25% of cases.61,69,81 Gastrointestinal hemorrhage and perforation are potential complications.93 Serologic studies usually show the p-ANCA pattern, although c-ANCA can also be seen (the inverse of ANCA types in WG).94 Elevated serum IgE is also a characteristic finding in CSS.59–61,69

A CSS-like syndrome develops as a rare complication in steroid-dependent asthmatics successfully treated with leukotriene receptor antagonists (e.g., pranlukast).95–99 This complication probably is related to steroid withdrawal facilitated by the drugs, which unmasks underlying CSS, rather than a manifestation of the drugs. To this point, a similar unmasking of CSS has occurred in asthmatic patients whose withdrawal from oral steroids was facilitated by inhaled steroids.99 Also, an unusual association between a CSS-like vasculitis and the illicit use of “free base” cocaine has been reported.100

Radiologic Features

CSS most commonly manifests radiologically as multifocal lung parenchymal infiltrates that change in location and size over time42,58,101 (Fig. 10-25). The infiltrates may also exhibit a peripheral distribution, thereby mimicking those of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Lung involvement by pulmonary consolidation may be widespread. Diffuse miliary nodules have also been reported.40,101 Cavitation of nodules is rare and when present should suggest superimposed infection.102 Eosinophilic pleural effusions may be seen in 29% of cases.42,101 Hilar lymphadenopathy is infrequent. The chest radiograph can be normal in appearance in as many as 25% of patients.42

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-18.)

High-resolution CT (HRCT) features of CSS most commonly consist of parenchymal opacifications (consolidation or ground-glass attenuation), followed in frequency by pulmonary nodules, bronchial wall thickening or dilatation, interlobular septal thickening, and normal anatomy.103 One case report described “stellate-shaped” peripheral pulmonary arteries and peribronchial and septal interstitial thickening. Small patchy opacities were also noted. These HRCT abnormalities correlated with eosinophilic infiltration and foci of eosinophilic pneumonia, respectively.104

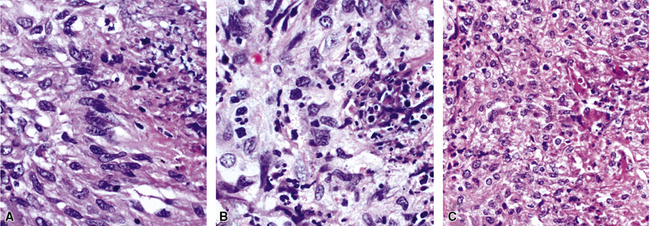

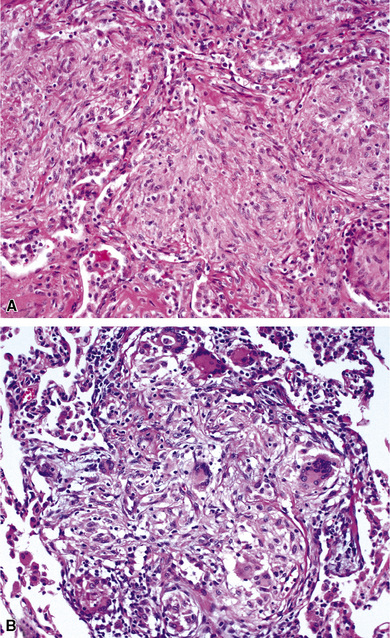

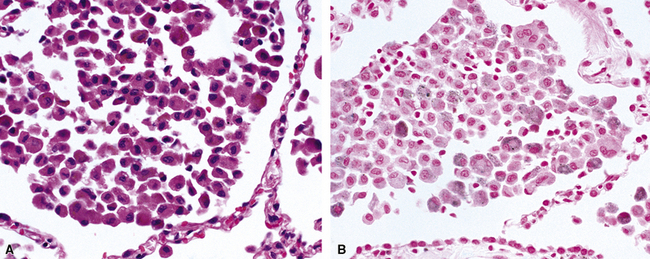

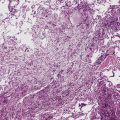

Pathologic Features

The findings on lung biopsy depend on the stage of the disease during which the biopsy is obtained and whether or not the patient has received therapy, particularly steroids. Lung biopsies from CSS patients in the full blown vasculitic phase may show asthmatic bronchitis, eosinophilic pneumonia (Fig. 10-26), extravascular stellate granulomas (Fig. 10-27), and vasculitis58,69 (Fig. 10-28). In some cases, the inflammatory lesions extend along the pleura and interlobular septa. The extravascular granulomas have a border of palisaded histiocytes and multinucleate giant cells, surrounding a central necrotic zone replete with eosinophils and eosinophil cellular debris. Such lesions have been called “allergic granulomas.” Vasculitis can affect arteries, veins, or capillaries. The vascular inflammatory infiltrates can be composed of chronic inflammatory cells, eosinophils, epithelioid cells, multinucleate giant cells, and neutrophils. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage and capillaritis (Fig. 10-29) can be seen.90,105 In patients who are partially treated, the pathologic (and clinical) features may be incomplete.101 Lung biopsy is not required for diagnosis, if pulmonary infiltrates are present in association with other systemic findings that fulfill the required diagnostic criteria.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of CSS includes eosinophilic pneumonia from any cause, WG,51 allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease (ABPFD),106 infection (especially parasitic and fungal),107 Hodgkin disease, and drug-induced vasculitis.108

Eosinophilic pneumonia and ABPFD lack systemic vasculitis, although some cases of eosinophilic pneumonia can show a mild non-necrotizing vasculitis, and “allergic granulomas” may be present. Features helpful in distinguishing CSS from WG are summarized in Table 4-5. Pathologic features similar to those of CSS can also be mimicked by certain parasitic infections, such as those caused by Strongyloides stercoralis109 and Toxocara canis.107 Therefore, parasitic infection should be carefully excluded when CSS is in the differential diagnosis on histopathologic grounds. Some fungal infections, especially those due to Aspergillus species and Coccidioides immitis, may be associated with granulomatous inflammation, prominent eosinophilia, and vasculitis. Rarely, Hodgkin disease with prominent eosinophils and vascular inflammation may be confused with CSS. Drugs such as carbamazepine also can cause a CSS-like syndrome, so attention should be paid to the patient’s drug history.108

Treatment and Prognosis

Most patients with CSS respond to systemic corticosteroids. In order to avoid irreversible organ injury, some authorities have favored treatment with cytotoxic immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide, from the outset.69 Azathioprine, interferon-α, and high-dose intravenous immune globulin have been used with apparent benefit in patients with severe, fulminant disease or in patients unresponsive to systemic corticosteroids. Plasma exchange occasionally has been used but appears to have no added benefit to that observed with treatment with systemic corticosteroids, with or without the addition of cyclophosphamide.110

Patients who die from CSS typically have cardiac complications such as congestive heart failure or myocardial infarction. Other, less common causes of death include renal failure, cerebral hemorrhage, gastrointestinal perforation or hemorrhage, status asthmaticus, and respiratory failure.69,111

Microscopic Polyangiitis

Microscopic polyangiitis encompasses the spectrum of vasculitic disorders that previously have been called systemic necrotizing vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and hypersensitivity vasculitis.112–115 An International Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitides116,117 defined microscopic polyangiitis as a vasculitis restricted to arterioles, venules, and capillaries.116,117 The designation polyangiitis was favored over polyarteritis because venules are affected as well as arterioles. Microscopic polyangiitis differs from polyarteritis nodosa in that it involves arterioles, venules, and capillaries, as opposed to medium-sized arteries.

Clinical Features

Systemic manifestations of microscopic polyangiitis are more common than pulmonary manifestations and include glomerulonephritis (in 97% of the cases), fever (in 62%), myalgia and arthralgia (in 52%), weight loss (in 45%), ear, nose, and throat symptoms (in 31%), and skin involvement (in 17%) (Table 10-4).117,118 Approximately 50% of the patients develop pulmonary involvement,116 and these persons are typically middle-aged or older (average age, 56 ± 17 years) when this occurs. Women are affected slightly more often than men (1.5:1 female-to-male ratio).118 Onset of symptoms is rapid in most patients, but up to 28% may have symptoms for more than 1 year before diagnosis.

Table 10-4 Microscopic Polyangiitis: Clinical Features at Presentation

| Manifestation | Number of Patients Affected (N = 29) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | 29 | 100 |

| Dyspnea | 26 | 90 |

| Cough | 26 | 90 |

| Hemoptysis | 23 | 79 |

| Chest pain | 5 | 17 |

| Crackles | 13 | 45 |

| Renal | 28 | 97 |

| Fever (temperature > 37.5°C) | 18 | 62 |

| Weight loss | 13 | 45 |

| Musculoskeletal | 15 | 52 |

| Arthralgias | 13 | 4 |

| Arthritis | 4 | 14 |

| Myalgia | 6 | 21 |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 9 | 31 |

| Epistaxis | 5 | 17 |

| Sore throat | 1 | 3 |

| Mouth ulcers | 2 | 7 |

| Hearing loss | 1 | 3 |

| Skin | 5 | 17 |

| Purpura | 4 | 14 |

| Nodules | 1 | 3 |

| Erythema elevatum diutinum | 1 | 3 |

| Bullae | 1 | 3 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 25 |

| Ocular | 7 | 25 |

| Episcleritis | 5 | 17 |

| Xerophthlamia | 2 | 7 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 2 | 7 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 | 3 |

From Lauque D, Cadranel J, Lazor R, et al. Microscopic polyangiitis with alveolar hemorrhage. A study of 29 cases and review of the literature. Groupe d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM“O”P). Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:222–233.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid typically shows acute hemorrhage or hemosiderin-laden macrophages when the lungs are involved. Kidney biopsies may show a necrotizing glomerulonephritis.118 More than 80% of patients have a positive ANCA, most often demonstrating the perinuclear type (p-ANCA).117 Microscopic polyangiitis is the most common cause of so-called pulmonary hemorrhage renal syndrome.117

Radiographic Features

The typical findings in microscopic polyangiitis are manifestations of pulmonary hemorrhage. Bilateral alveolar infiltrates are seen on plain chest films, and ground-glass attenuation is seen on CT scans. The lower lung zones may be most frequently affected.118

Pathologic Features

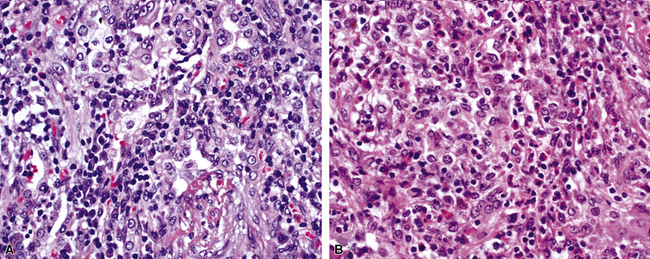

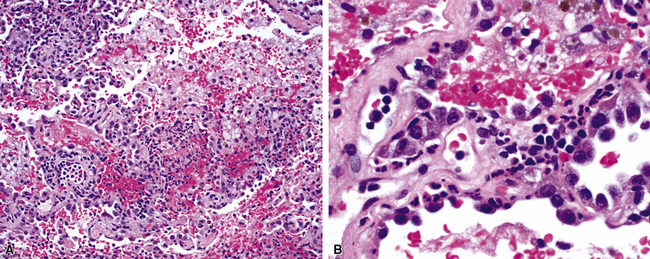

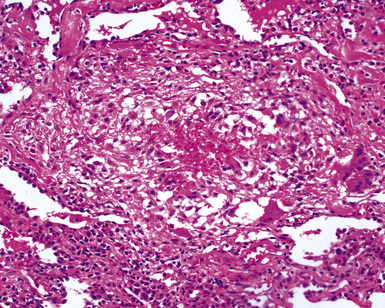

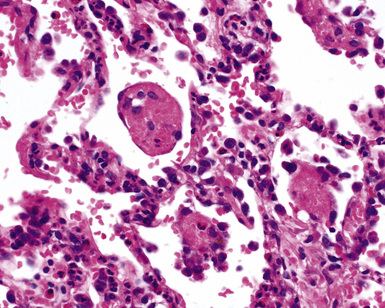

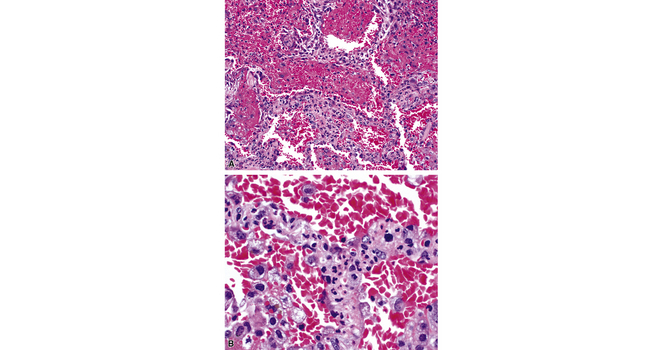

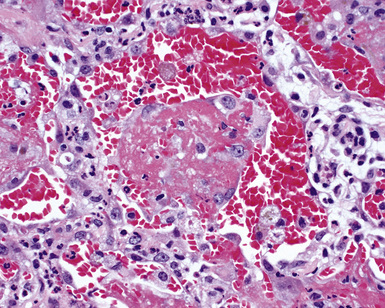

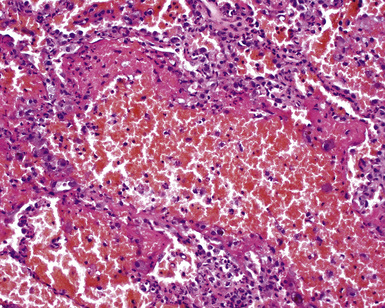

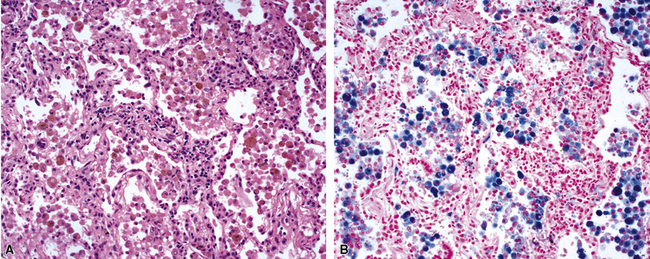

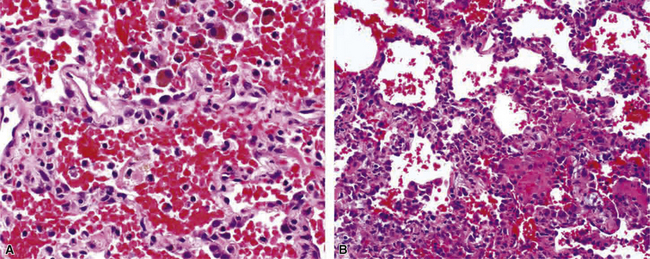

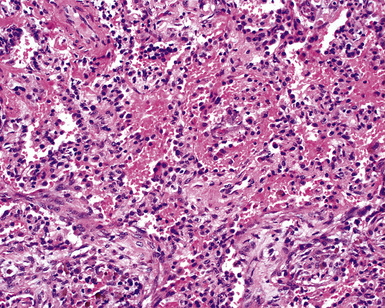

Surgical lung biopsies in microscopic polyangiitis typically show pulmonary hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages in alveolar spaces, and neutrophilic capillaritis37,117 (Fig. 10-30). At scanning magnification, neutrophilic capillaritis often appears as scattered foci of increased alveolar wall cellularity, in a background of alveolar hemorrhage (Fig. 10-31). Closer inspection reveals the presence of neutrophils within the alveolar walls, sometimes spilling over into the surrounding alveolar spaces. In severe cases, the neutrophils may fill the alveoli and focally resemble an acute infectious pneumonia (Fig. 10-32). Identification of distinctive fibrinoid necrosis of capillary walls is often not possible. Alveolar fibrin may accompany the lesions of capillaritis, sometimes in a polypoid fashion (Fig. 10-33). As the lesions of capillaritis heal, polypoid plugs of organizing fibrosis may be seen, sometimes resulting in a organizing pneumonia pattern (Fig. 10-34) (previously referred to as a “BOOP pattern”). The presence of hemosiderin (typically within alveolar macrophages) is essential for an accurate diagnosis, because blood alone may be present in lung biopsies as an artifactual finding.

Hyaline membranes (Fig. 10-35) identical to those of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) may also be seen.37,119 In some cases it may be difficult to distinguish hemorrhagic DAD from a diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome with capillaritis. Pulmonary fibrosis36,37 and progressive obstructive airway disease with emphysematous features120,121 have also been reported in patients with microscopic polyangiitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for microscopic polyangiitis includes hemorrhagic lung infections, WG with prominent capillaritis, Goodpasture syndrome, certain systemic collagen vascular diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]) and other small-vessel vasculitides, such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura and cryoglobulinemia, and even certain rare drug reactions (e.g., diphenylhydantoin).122

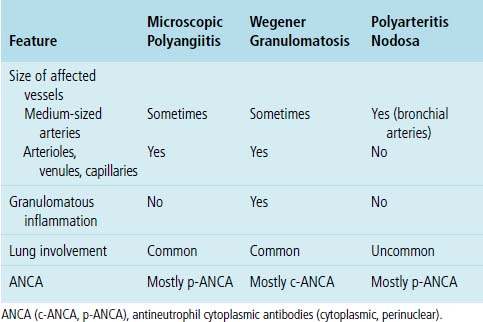

As mentioned earlier, microscopic polyangiitis is distinguished from polyarteritis nodosa by the involvement of vessels smaller than medium-sized arteries in microscopic polyangiitis, such as arterioles, venules, and capillaries117 (Table 10-5).

Finally, microscopic polyangiitis must be distinguished from a heterogeneous group of vasculitic disorders affecting venules, capillaries, and arterioles, some of which are associated with drugs or other agents113–115,122,123 (Box 10-4). Microscopic polyangiitis is not associated with immune deposits in lung as are some other types of small-vessel vasculitis, such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, serum sickness, and lupus vasculitis.116,117 Other conditions known to produce small-vessel vasculitis (listed in Box 10-4) can typically be excluded on clinical and serologic grounds.

Box 10-4 Microscopic Polyangiitis and Other Conditions Associated with Small-Vessel Vasculitis

Data from Calabrese LH, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of hypersensitivity vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1108–1113; Churg J. Nomenclature of vasculitic syndromes: a historical perspective. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;18:148–153; Swerlick R, Lawley T. Small-vessel vasculitis and cutaneous vasculitis. In: Churg A, Churg J, eds. Systemic Vasculitides. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1991:193–201; Jennette J, Falk R. Small-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1512–1523; and Churg J, Churg A. Idiopathic and secondary vasculitis: a review. Mod Pathol. 1989;2:144–160.

Treatment and Prognosis

Microscopic polyangiitis is treated with immunosuppressive agents.117 Lauque and colleagues treated a group of 29 patients using corticosteroids (in 100%) with cyclophosphamide (in 79%), plasmapheresis (in 24%), dialysis (in 28%), and mechanical ventilation (in 10%).118 The 5-year survival rate was 68%, with causes of death divided equally between vasculitis and side effects of treatment. Complete recovery occurred in most patients (69%). Pulmonary function abnormalities persisted in 24%, and 11 patients relapsed, 2 of whom died of alveolar hemorrhage.118

Vasculitic Syndromes That Uncommonly Affect the Lung

Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis

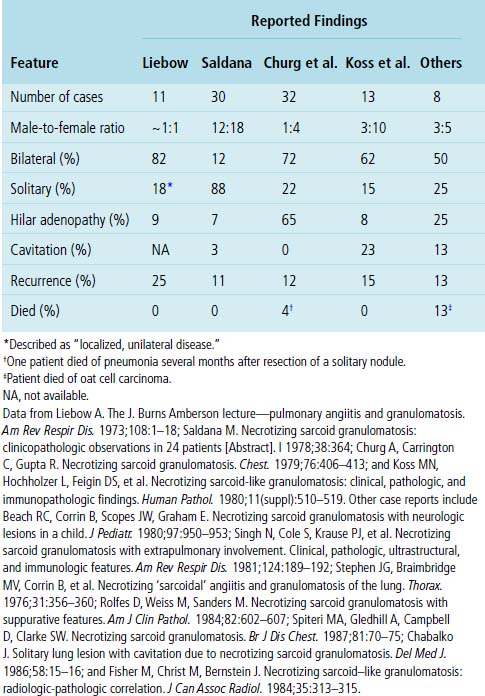

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis is a rare granulomatous disease that primarily affects the lungs. Nodular masses of confluent sarcoid-like or epithelioid granulomas are seen in the lung parenchyma, often with extensive areas of necrosis and vasculitis. Debate continues over whether necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis is a vasculitic syndrome, a variant of sarcoidosis, or simply a manifestation of unusual infection. The principal argument against the disorder’s being a vasculitic syndrome is that it is not a systemic vasculitic disorder and the lung pathology is primarily that of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation rather than vasculitis. A case of necrotizing sarcoid was recently reported in a patient who had family members with typical sarcoid, potentially lending further support to the theory of a primary granulomatous disorder.124

Clinical Features

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis is typically a disease of adults. A summary of clinical and radiologic features reported in case studies is presented in Table 10-6. The average age for patients who develop the disease is 50, but it can occur from adolescence to late adulthood.25,79,125 Women are affected twice as often as men.126,127 The usual presentation includes cough, fever, chest pain, dyspnea, malaise, and weight loss.62,126,128 Up to one fourth of patients may be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Extrapulmonary manifestations are uncommon, with rare reports of uveitis and hypothalamic insufficiency.63,129–131 Upper airway disease, glomerulonephritis, and systemic vasculitis are not expected findings. To date, positive ANCAs have not been reported in this disease.

Radiologic Features

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis usually manifests as bilateral, multifocal parenchymal nodular opacities. Nodules may either be well marginated or have ill-defined borders (Fig. 10-36). Like the granulomas of sarcoidosis, lesions typically have a bronchovascular and subpleural distribution, but unlike in sarcoidosis, they may be more numerous in the lower lung zones.42,62,79,80,132 Solitary lesions and parenchymal consolidations may occur but are unusual manifestations.

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-24.)

On CT scans, cavitation and heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the lesions may be seen (Fig. 10-37), correlating with intralesional necrosis.129 Pleural involvement with thickening or effusion may also be observed.132 Hilar lymphadenopathy is variable and not seen as frequently as in sarcoidosis.56

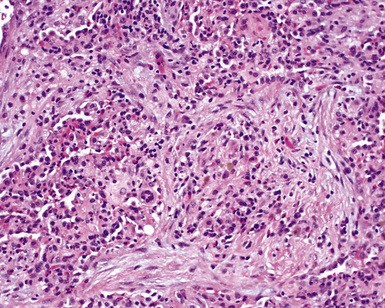

Pathologic Features

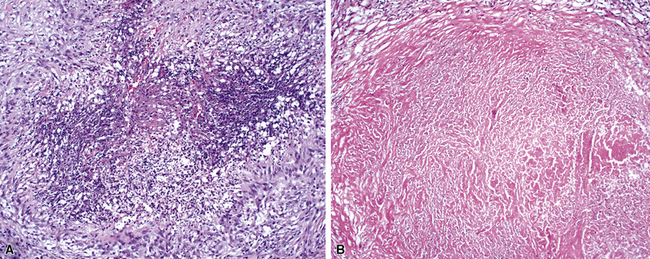

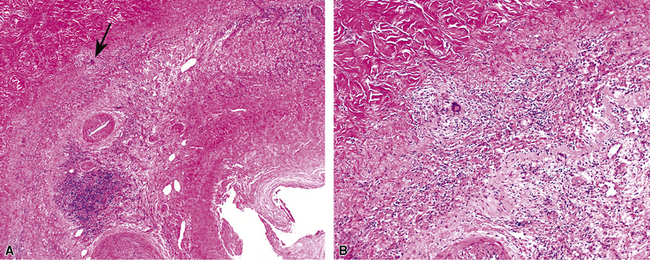

Confluent non-necrotizing granulomas form large nodules in the lung parenchyma (Fig. 10-38). Large zones of necrosis are present in the nodules (Fig. 10-39), and vasculitis (Fig. 10-40) is typically present. The granulomas in necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis resemble those of sarcoidosis, except for the presence of necrosis, with tight clusters of giant cells and epithelioid cells (Fig. 10-41). One can also see a sarcoidal pattern of lung involvement with a lymphangitic distribution to the granulomas.56,62,127 In addition to the large zones of necrosis, smaller foci of necrosis often are present.56

Figure 10-39 Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis: large zones of necrosis. Large zones of necrosis are seen at right.

The vasculitis of necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis can affect both arteries and veins. Three patterns of vasculitis can be seen: necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 10-42), giant cell vasculitis (Fig. 10-43), and infiltration by chronic inflammatory cells.133 Necrotizing granulomas may be present circumferentially along the vascular walls (Fig. 10-44).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis includes granulomatous infection, nodular sarcoidosis, and WG. The most important of these entities, and the most difficult to exclude, is granulomatous infection,56,61 especially because granulomatous infections caused by mycobacteria and fungi can produce both vasculitis and sarcoid-like granulomas.51,52 Some investigators regard necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis as representing the subset of sarcoidosis referred to as “nodular sarcoidosis,” but true necrosis, as seen in this disorder, is not typically present in the nodular form of sarcoidosis. The key features distinguishing necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis from WG are summarized in Table 10-7.

Table 10-7 Wegener Granulomatosis versus Necrotizing Sarcoidosis: Distinguishing Features

| Clinical/Pathologic Feature | Wegener Granulomatosis | Necrotizing Sarcoidosis |

|---|---|---|

| Lung involvement | 66–85% | 100% |

| Extrapulmonary involvement | 90–100%ENT, kidney, skin, neurologic | ≤10%Ocular, neurologic |

| ANCA | Yes | No |

| Histopathologic pattern | ||

| Sarcoidal granulomas | Rare | Characteristic |

| Vasculitis | Characteristic | Characteristic |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; ENT, ear, nose, and throat.

Treatment and Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis is excellent.127,134 Localized disease can be cured by surgical resection alone. Patients with bilateral opacities or nodules may respond to systemic corticosteroids. A small percentage of patients will have persistent opacities62,63 or will experience a relapse.56,135 The only deaths reported in patients with necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis have been due to opportunistic infections, so cytotoxic immunosuppression generally is not recommended.62

Giant Cell (Temporal) Arteritis

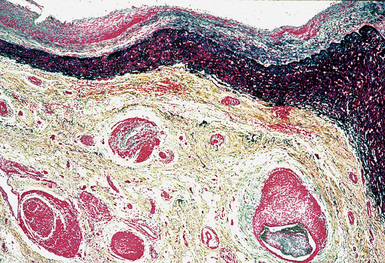

Giant cell arteritis is a vasculitis that most commonly involves the temporal arteries in older individuals. Vascular lesions include giant cells, typically centered on the vascular elastic lamina (Fig. 10-45). Lower respiratory tract involvement is extremely rare, although the disease can be associated with upper respiratory tract symptoms in approximately 10% of patients.88 When the lungs are involved, patients may have nodules,136,137 interstitial opacities,138 and unilateral pleural effusions on chest radiographs.88 Pulmonary arterial involvement is rarer still,139 but giant cell arteritis can affect the pulmonary trunk and main pulmonary arteries, as well as large and medium-sized intrapulmonary elastic arteries.139 Histologically the vasculitis shows medial and adventitial chronic inflammation with included giant cells. This causes destruction of the elastic laminae sometimes with focal fibrinoid medial necrosis.139 Bronchoscopic biopsies may show granulomatous inflammation of pulmonary arteries and fragmented elastic fibers.136,139 Giant cell arteritis can be distinguished from WG, necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis, CSS, and granulomatous infections by the absence of parenchymal inflammation.139 The temporal artery involvement and older age of patients with giant cell arteritis distinguishes them from those with Takayasu arteritis.139

A very rare disorder known as “idiopathic isolated pulmonary giant cell arteritis” has also been described.140–142 The disease is limited to the lungs. Dyspnea on exertion may be a presenting manifestation, but patients usually lack hemoptysis, fever, or elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The vasculitis is usually an unsuspected finding seen first in a surgical or an autopsy specimen.140,141 Histologically, organized arterial thrombi with recanalization are identified, and narrowing of large pulmonary arteries is seen. The vasculitis is characterized by a destructive inflammatory infiltrate of giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes causing fragmentation of elastic laminae.140–142 Peripheral lung infarcts can occur.

Disseminated visceral giant cell angiitis is another rare form of giant cell arteritis that affects extracranial small arteries and arterioles, including those in the lung. This is a very rare condition, with only five reported cases, in males, three of whom had lung involvement.143,144 In all of these cases, the disorder was recognized as an incidental autopsy finding.143 Extracranial small arteries and arterioles were affected, and each patient demonstrated involvement of at least three of the following organs: heart, lung, kidneys, liver, pancreas, and stomach. The vasculitis showed prominent multinucleate giant cells of both foreign body and Langerhans types, but most of the inflammatory cells consisted of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. A relationship has been proposed between sarcoidosis and disseminated visceral giant cell arteritis, but the occurrence of these two manifestations together is so rare that it is difficult to confirm.145–147

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Classic polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis that involves arteries of medium and small size (Fig. 10-46). It can involve virtually any organ but rarely affects the lungs. Most cases previously reported as polyarteritis nodosa with lung involvement probably were examples of CSS114,148–150 or possibly small-vessel vasculitis (i.e., microscopic polyangiitis). Polyarteritis nodosa differs from CSS and microscopic polyangiitis in that only arteries are affected. The tissue eosinophilia and extravascular granulomas characteristic of CSS are not seen. Polyarteritis nodosa differs from microscopic polyangiitis in that medium-sized arteries are affected (primarily bronchial arteries),12,150 whereas in microscopic polyangiitis, smaller arteries, venules and capillaries typically manifest the disease.116,117

Takayasu Arteritis

Clinical Features

Takayasu arteritis most commonly affects women less than 40 years of age.151 Pulmonary arteries are involved in 12% to 86% of patients with the disease,151–154 and rarely, pulmonary artery involvement may be the presenting manifestation.155 Takayasu arteritis may affect the kidneys, heart, skin and gastrointestinal tract.156 Because it is difficult to obtain tissue biopsy specimens from large vessels such as the aorta or pulmonary artery, the diagnosis is usually established by angiography. Pulmonary artery stenosis, irregular narrowing, and occlusion may be seen.152,153,157 Fistulas between pulmonary arteries and systemic arteries may occur.158

Radiographic Features

CT scan findings in Takayasu arteritis frequently include areas of low attenuation in the lung, presumably on the basis of regional hypoperfusion related to upstream arteritis.159 Subpleural linear reticular changes and pleural thickening also occur.159

Pathologic Features

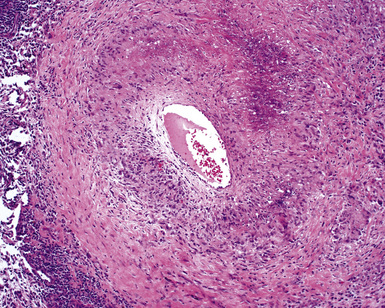

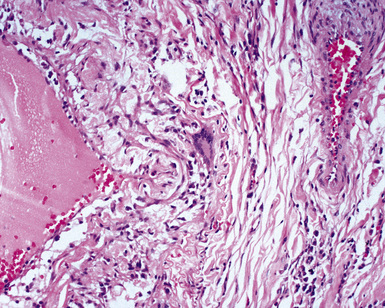

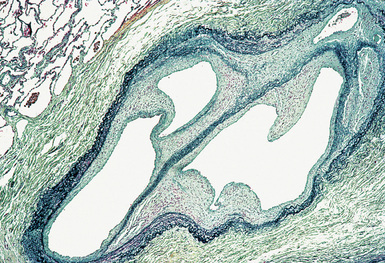

Takayasu arteritis involves the adventitia, media, and intima of large elastic pulmonary arteries (Fig. 10-47). Infiltration by lymphocytes, macrophages, and giant cells is characteristic. Thrombi may also be seen. There is progression to diffuse or nodular fibrosis of the artery wall with disintegration or loss of elastic fibers.160,161 The fibrosis can result in stenosis or obliteration of the vascular lumen and cause aneurysm formation or dilatation of the artery. Matsubara and associates described a stenosis-recanalization phenomenon they called “blood vessels in blood vessels,” occurring within the pulmonary elastic and muscular arteries.161

Figure 10-47 Takayasu arteritis. The wall of this pulmonary artery is infiltrated by lymphocytes and giant cells.

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-29.)

Behçet Syndrome

Behçet syndrome is a multisystem inflammatory disorder characterized by skin lesions, oral and genital ulcers, and iridocyclitis. Debate continues over the nature of the disease. The etiology is unknown, but environmental, genetic, viral, bacterial, and immunologic factors have been implicated in its pathogenesis. The lung manifestations are clearly vasculitic, but an immune complex–mediated hypersensitivity reaction has been proposed for the mucocutaneous lesions, and an association with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B51 has been identified.163

Clinical Features

Behçet syndrome has a worldwide distribution but is most commonly a disease of the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, and Japan.164,165 The disease typically affects individuals between adolescence and middle age. The diagnosis is based primarily on clinical criteria (Box 10-5). The clinical feature that is common to all patients with Behçet syndrome is recurrent painful aphthous oral or genital ulcers. Oral ulceration occurring more than three times in 1 year is required to meet the diagnostic criteria for the disease. These lesions must be distinguished from ulcers related to viral infection such as herpes simplex, and other diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Symptoms of pulmonary involvement include dyspnea, cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis.165 Males are more likely to develop lung manifestations, particularly hemoptysis.165,166 The presence of circulating immune complexes in patients with active pulmonary disease suggests that immune complexes may be important in the pathogenesis of the lung involvement.166,167

Radiographic Features

Air space consolidation consistent with pulmonary hemorrhage, lung infarction, and pulmonary artery aneurysms may be seen when the lungs are involved.168,169 Thoracic involvement in the patient with Behçet syndrome can sometimes be suggested on CT images by the presence of thrombosis in the pulmonary arteries or in the superior vena cava. Characteristic aneurysms of the pulmonary arteries can also occur.168,169 Pulmonary aneurysms and thromboses can be detected with angiography as well.165

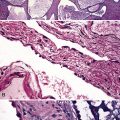

Pathologic Features

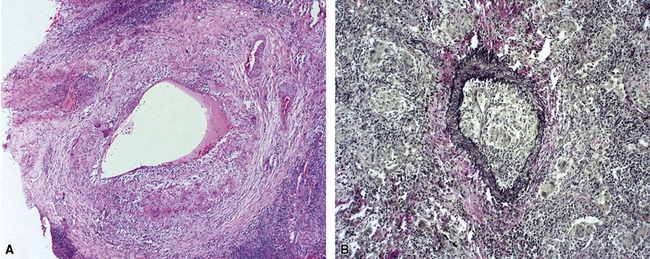

Pulmonary involvement is characterized by a lymphocytic and necrotizing vasculitis that involves pulmonary arteries of all sizes, veins, and alveolar septal capillaries (Fig. 10-48). Additional findings include aneurysms of elastic pulmonary arteries, arterial and venous thromboses(Fig. 10-49), pulmonary infarcts (Fig. 10-50), bronchial erosion by pulmonary artery aneurysms, and arteriobronchial fistulas.165,170,171 Perivascular adventitial fibrosis may be prominent. Collateral vessels lacking elastic lamellae may develop in the periadventitial fibrous tissues around thrombosed arteries and aneurysms (Fig. 10-51). Hemorrhage172 and acute interstitial pneumonia173 may occur as life-threatening pulmonary complications.

Figure 10-48 Behçet syndrome: vasculitis. The wall of this small artery is infiltrated by lymphocytes.

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-30.)

(From Travis WD, Colby TV, Koss MN, et al, eds. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. In: King DW, ed. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002, Figure 4-31.)

Treatment

A variety of treatments have been used to address the mucocutaneous manifestations of the disease, including oral colchicine, topical anesthetics, and corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, or systemic). Thalidomide and dapsone have also been shown to be effective. Aggressive immunosuppression with combined systemic corticosteroids and another agent (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, chlorambucil) may be necessary when significant ocular, neurologic, gastrointestinal, and vascular manifestations occur. Patients who develop thromboses require anticoagulation.166 Severe hemoptysis may require surgical intervention.172 The clinical course of Behçet syndrome is characterized by exacerbations and remissions. Over time, the disease may decrease in severity.

Secondary Vasculitis

Pulmonary Infection and Septic Emboli

When pulmonary vessels are involved by inflammation and necrosis in the setting of infection, secondary vasculitis should always be a strong consideration. Certain bacterial pneumonias, especially those caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa174 and Legionella pneumophila,175 are well known for their tendency to invade and produce necrosis of blood vessel walls. The necrotizing granulomas produced in response to fungal and mycobacterial infections commonly involve blood vessel walls, causing potential confusion with vascular involvement by WG.52 Necrotizing vasculitis may also be a consequence of angioinvasive fungal infections in the immunocompromised patient, especially infections due to Aspergillus and Mucor species. Such vasculitis may be granulomatous and frequently causes pulmonary infarction. Pulmonary vasculitis can also accompany certain parasitic pulmonary infections such as Dirofilaria immitis, Schistosoma, and Wuchereria infections. In HIV-infected patients, vasculitis can even be be a rare complication of Pneumocystis pneumonia.176

Classic Sarcoidosis

Classic sarcoidosis can produce so-called granulomatous vasculitis (involvement of blood vessel walls by typical sarcoid granulomas) as an incidental histologic finding in surgical lung biopsies (see Chapter 7, Chronic Diffuse Lung Diseases).177

In rare instances, a systemic vasculitis can occur in patients with sarcoidosis. Fernandes and colleagues reported 6 cases in which patients exhibited features of both sarcoidosis and systemic vasculitis and reviewed 22 similar cases that had been previously reported.178 The group included 13 children and 15 adults who developed fever, peripheral adenopathy, hilar adenopathy, rash, pulmonary parenchymal disease, musculoskeletal symptoms, and scleritis or iridocyclitis.178

Radiologic Features

Arteriography demonstrated involvement of medium-sized or large arteries in approximately one half of the patients and features of small-vessel disease in the remaining patients.178

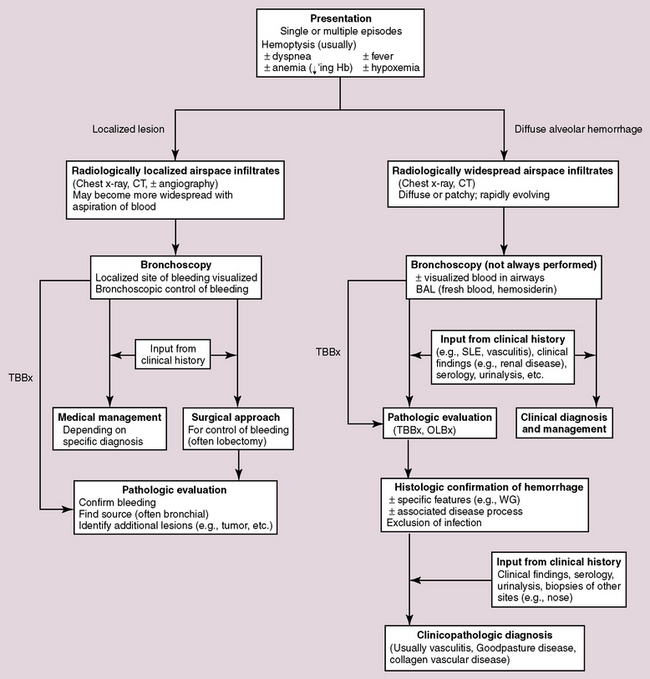

Pulmonary hemorrhage

Hemorrhage in the lung may occur as a localized phenomenon or as a diffuse disease. Clinically significant hemorrhage is nearly always accompanied by hemoptysis. When blood is identified in the lung biopsy specimen, the question frequently arises as to whether it is a real finding or simply an artifact related to the procedure. Real pulmonary hemorrhage can be caused by a number of unrelated mechanisms. Pulmonary vasculitis and vasculitic syndromes, such as Goodpasture syndrome, are important clinical causes of lung hemorrhage and typically require urgent therapy. Because the differential diagnosis is broad in scope, and the consequences of accurate diagnosis are significant, a diagnostic approach to pulmonary hemorrhage is presented here. A useful algorithm for this exercise is presented in Figure 10-52.

Clinical View of Pulmonary Hemorrhage

The occurrence of hemoptysis is alarming to patient and clinician alike. The potential causes of hemoptysis are presented in Box 10-6. The distinction of localized from diffuse hemorrhage is important for management purposes but is not always feasible. With the classic presentation of sudden unilateral chest pain followed by expectoration of bright red blood, pulmonary embolus is usually high on the list of diagnostic possibilities. In most instances, however, the clinician must rely heavily on the radiologic findings in the approach to the patient with hemoptysis, because the physical examination is typically limited in defining the origin or extent of any hemorrhagic event. Bronchoscopy plays an important role as well in defining a potential localized source of bleeding and documenting the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages (siderophages) in lavage specimens examined under the microscope. Localized causes of pulmonary hemorrhage are often straightforward and include thromboembolism, tumor, abscess, bronchiectasis, and broncholithiasis. Dieulafoy disease is a rare entity characterized by an abnormal submucosal location of arterial branches. This abnormality is more frequently described in the gastrointestinal tract, but rare bronchial cases have been reported.179 At times, localized hemorrhage may be life-threatening, requiring lobectomy for control. In this situation, blood may be abundant in the lung parenchyma, but no exact origin for bleeding can be identified (analogous to colectomy for massive hemorrhage associated with diverticulosis). Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage is more complicated in terms of etiology and will be the main focus here.

Box 10-6 Causes of Hemoptysis

From Colby TV, Fukuoka J, Ewaskow SP, et al. Pathologic approach to pulmonary hemorrhage. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5:309–319 (data adapted from Fraser R, Müller N, Colman N, Paré P. Fraser and Paré’s Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999).

Morphologic Approach to Pulmonary Hemorrhage

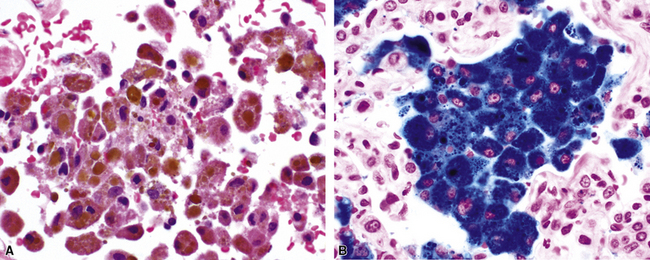

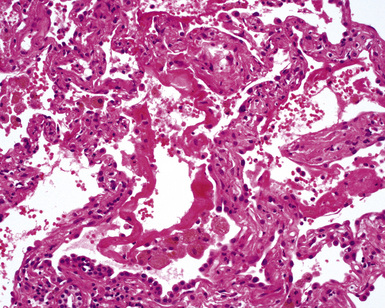

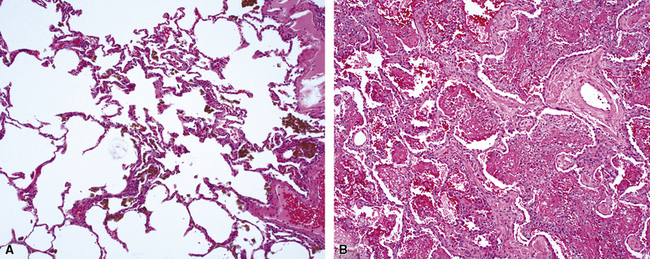

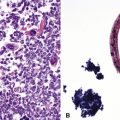

Not all patients with hemoptysis have histologic evidence of hemorrhage and conversely, not all hemorrhage, or hemosiderin, seen in lung tissue is associated with hemoptysis or other evidence of lung hemorrhage. For the pathologist, the first step in the evaluation of extravascular blood seen in a biopsy specimen is to ascertain the context in which it occurs. Clinically significant hemorrhage rarely is seen in biopsy specimens as blood alone. When intact red cells abound, the most common cause is trauma related to the biopsy procedure, especially in the case of thoracoscopic biopsies because of intraoperative manipulation.180 In artifactual hemorrhage (Fig. 10-53), fibrin, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and cellular reactive changes in adjacent alveolar walls typically are lacking. Also, focal areas of organization may be seen within the air spaces in true hemorrhage and may be a useful marker for associated lung injury.

The Prussian blue histochemical stain for iron is sometimes cited as a means of distinguishing siderophages from hemorrhage from macrophages seen in smokers (Fig. 10-54), but caution must be exerted, because so-called smoker’s macrophages may contain considerable amounts of stainable iron (Fig. 10-55). The pigment in smoker’s macrophages tends to be finely granular and light brown, typically admixed with punctate black pigment. True siderophages, on the other hand, are characterized by the presence of coarse, golden brown pigment that is minimally refractile (Fig. 10-56). Also, it is important to keep in mind that the Prussian blue stain reacts with other iron-associated substances in the lung, in addition to hemosiderin. Occupational dusts may contain iron and simulate siderophages in the patient with pneumoconiosis.

When all of the elements in the biopsy add up to real hemorrhage, and the patient has radiologic evidence of diffuse alveolar infiltrates, the differential diagnosis becomes one of DAH. The potential causes of DAH are presented in Box 10-7. It is useful to divide DAH into two forms characterized by the presence or absence of capillaritis, respectively. Rapidly evolving acute DAH is often accompanied by capillaritis and evokes a differential diagnosis of narrow scope.

Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

The histopathology of DAH is stereotypical, regardless of etiology. This fact is important for the surgical pathologist, because a specific diagnosis requires clinical and serologic data.66 A generic designation such as “[acute] and/or [organizing] pulmonary hemorrhage [with] or [without] capillaritis,” followed by a differential diagnosis is often all that is required.

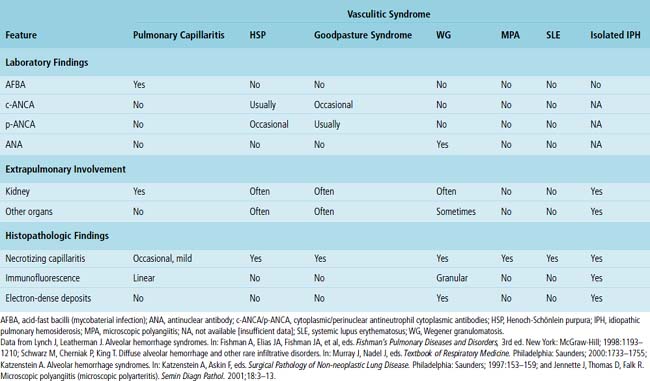

Most causes of DAH are immunologically mediated. Some of these diseases have specific patterns of immunoglobulin deposition that can be visualized in tissue sections using immunofluorescence staining of a specially prepared portion of the surgical lung biopsy. When such staining is performed correctly, the results can be diagnostically useful and visually striking. Fortunately, in practice today, immunofluorescence staining is rarely necessary for diagnosis because serologic studies are widely available and reasonably specific for the subtypes of DAH. For those forms of DAH mediated by immune complexes, deposits in the lung tissue can also be visualized ultrastructurally. Again, although historically interesting, electron microscopy really plays no role in the diagnosis of DAH today. A comparison of the major defined pulmonary vasculitis syndromes is presented in Table 10-8.

Specific Forms of Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

Goodpasture Syndrome

Goodpasture syndrome (antiglomerular basement membrane antibody disease) affects persons of all ages and both sexes, but the typical patient is a young male smoker.181 Circulating antibodies directed against the non-collagenous domain of the alpha 3 chain of collagen type IV are identified in patients with Goodpasture syndrome. Using immunolocalization techniques, these antibodies can also be detected in the lung and kidney, where they are deposited in association with basement membranes. The histopathology of Goodpasture syndrome in the lung is not specific and resembles that in other DAH syndromes (Fig. 10-57). Capillaritis may be present but generally is not prominent.182 Hyaline membranes may accompany the pulmonary hemorrhage of Goodpasture syndrome (Fig. 10-58).

Wegener Granulomatosis

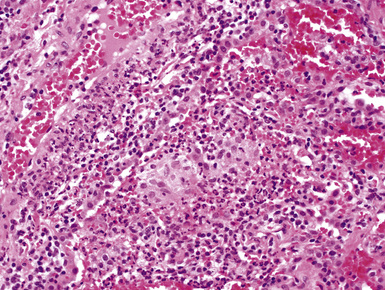

A minority of patients with WG present with pulmonary hemorrhage, although hemorrhage may occur in the course of the disease.182 The typical systemic and serologic features of WG, as outlined earlier, often accompany DAH, making a clinical diagnosis possible even when the lung biopsy lacks diagnostic features. DAH in WG is often attended by dramatic capillaritis (Fig. 10-59). A careful search may reveal small foci of collagen necrosis, typically involving the adventitia of pulmonary arteries and the collagen surrounding bronchi and bronchioles. The presence of scattered giant cells may also be helpful in suggesting WG as a possible underlying disorder in DAH.

Microscopic Polyangiitis

Microscopic polyangiitis has been discussed in detail earlier in this chapter. When alveolar hemorrhage dominates the presentation, distinction from WG may be impossible on biopsy findings alone (Fig. 10-60). The frequency of extrathoracic site involvement in the two diseases and the common presence of p-ANCA in microscopic polyangiitis usually suffice to differentiate them.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

DAH occurs more commonly in SLE than in any other connective tissue disease. Nevertheless, DAH is the presenting manifestation of the disease in only 11% of patients with SLE.183 Patients with lupus nephritis are at increased risk for DAH. The histopathology of DAH in SLE is similar to that of other pulmonary hemorrhage syndromes, including the presence of capillaritis (Fig. 10-61).

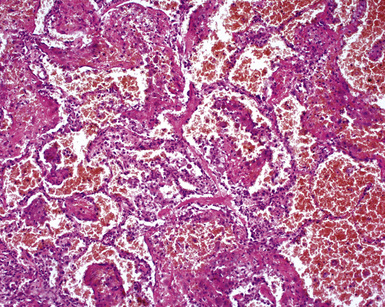

Idiopathic Pulmonary Hemosiderosis

Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis affects children more commonly than adults and is characterized by recurrent episodes of DAH with hemoptysis. Patients are frequently anemic. An immunologic mechanism for the disease has not yet emerged, and capillaritis is not seen. The histopathology of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis is dominated by the presence of hemosiderin (Fig. 10-62). Interstitial widening with collagen deposition occurs over time.184

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Like idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura affects children more often than adults.122,181,183,185 Alveolar hemorrhage is rare and typically overshadowed by other systemic manifestations of the disease—such as involvement of the skin, joints, and kidneys. The histopathologic changes of pulmonary hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura are nonspecific and resemble those of other pulmonary hemorrhage syndromes.

Isolated Pulmonary Capillaritis

Isolated pulmonary capillaritis is a rare form of DAH in which no associated immunologic or systemic manifestations are found. There may be overlap between this disorder, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis in adults, and the group of diseases designated by Travis and coworkers as “idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage.”66 The histopathology of isolated pulmonary capillaritis is similar to that in other alveolar hemorrhage syndromes that include capillaritis.

1 Watts R.A., Scott D.G. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15(1):11-16.

2 Travis W.D. Vasculitis. In: Tomashefski J.F., Cagle P.T., Farver C.F., Fraire A.E., editors. Dail and Hammar’s Pulmonary Pathology. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2008:1088-1138.

3 Travis W.D., et al. Pulmonary vasculitis. King D.W., editor. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. Travis W.D., Colby T.V., Koss M.N., et al, editors. Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. American Registry of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, 2002;233-264.

4 Guinee D.Jr, Jaffe E., Kingma D., et al. Pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Evidence for a proliferation of Epstein-Barr virus infected B-lymphocytes with a prominent T-cell component and vasculitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:753-764.

5 Nicholson A.G., Wotherspoon A.C., Diss T.C., et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: evidence that some cases represent Epstein-Barr virus–associated B-cell lymphoma. Histopathology. 1996;29:317-324.

6 Travis W.D., et al. Pathology and genetics. In: Travis W.D., Brambilla E., Müller-Hermelink H.K., Harris C.C., editors. Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon: IARC Press, 2004.

7 Wegener F. Generalized septic vascular diseases [Translation]. Verh Dtsch Path Ges. 1936;29:202-210.

8 DeRemee R.A., McDonald T.J., Harrison E.G.Jr, Coles D.T. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Anatomic correlates, a proposed classification. Mayo Clin Proc. 1976;51:777-781.

9 Carrington C.B., Liebow A.A. Limited forms of angiitis and granulomatosis of Wegener’s type. Am J Med. 1966;41:497-527.

10 Stone J.H. Limited versus severe Wegener’s granulomatosis: baseline data on patients in the Wegener’s granulomatosis etanercept trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2299-2309.