20 Malignant and Borderline Mesothelial Tumors of the Pleura

The number of publications on the pathologic features of primary pleural mesothelial tumors has gone from meager to innumerable in a little over 40 years. As late as the 1960s, a strong opinion in the medical community held that a diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma (MM) could not be established with certainty during life and that neoplasms effacing the serosal lining of the chest cavity were probably metastatic from other sites.1 Accordingly, a diagnosis of MM was largely consigned to autopsy pathologists.

Another problem, which persists to some extent even today, relates to the widely cited paradigm for classification of mesothelial tumors that was first advanced by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931.2 Those authors divided these lesions into four broad categories, depending on whether they were benign or malignant and localized or diffuse. However, using that model, such neoplasms as solitary fibrous tumors and pleural sarcomas, which are not mesothelial at all, are still confused by some clinicians with true MMs.

Malignant Mesothelioma

Clinical Findings in Pleural Mesothelioma

Patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma are typically adults older than 50 years of age,3–6 but there have also been several well- documented examples of this tumor in children.7–9 Very rarely, familial clustering of MM has been reported, with parent-child or sibling-sibling combinations being represented.10–13 To date, there have been no reports of spouse-spouse concurrences.

The most common presentation of MM is with progressive shortness of breath.4,5,14,15 Unilateral chest pain is also relatively frequent, and this may or may not have pleuritic characteristics. Another rarer manifestation is that of flulike illness, with malaise, anorexia, low-grade fever, myalgias, and weight loss.16–19 Distant metastasis of MM to extrathoracic lymph nodes or other anatomic sites at presentation is extraordinarily uncommon20,21 but can represent a diagnostic challenge for pathologists.

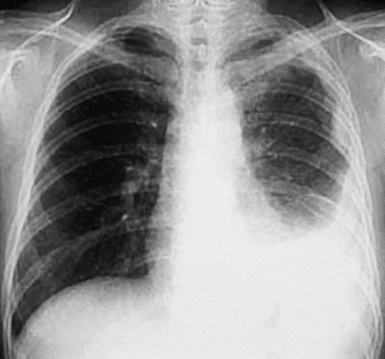

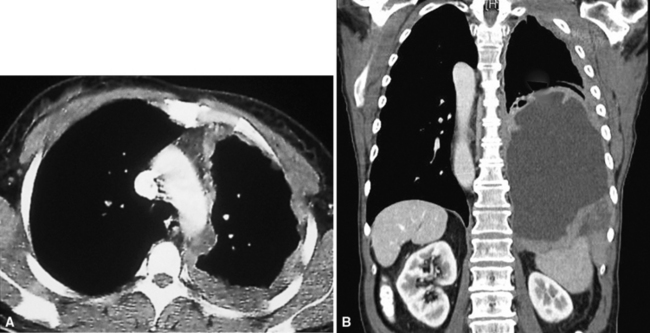

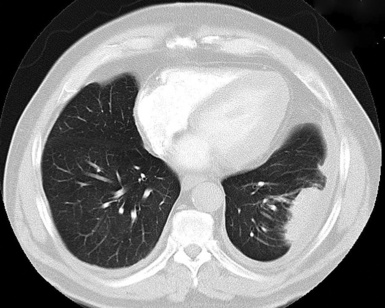

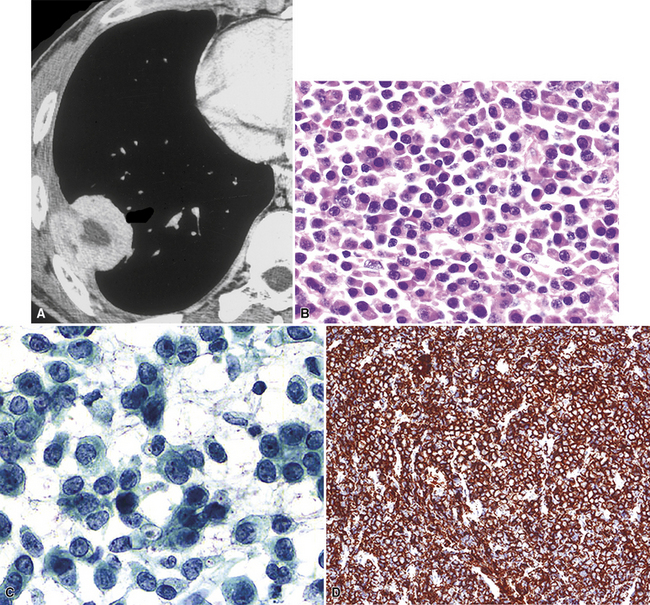

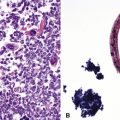

Plain film chest radiographs typically show a unilateral pleural effusion, which may be massive in volume despite relatively minor symptoms (Fig. 20-1). Reimaging after thoracentesis often reveals diffuse pleural thickening; more rarely, a single discrete pleural mass may be observed.22–25 Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the thorax are more sensitive than plain films for demonstrating tumor volume and invasion of contiguous anatomic structures25–27 (Fig. 20-2). They are also superior for showing the presence of pleural plaques and pleural calcifications, which are sensitive markers of asbestos exposure. One or both of these markers are seen in 85% or more of all individuals who are exposed to asbestos at an above-background level.28,29

Other laboratory abnormalities in MM cases are relatively few and nondescript. However, a substantial proportion of patients have tumor-related thrombocytosis, with platelet counts greater than 400,000 mm3.30–33This may relate to the elaboration of interleukin-6 by the tumor cells, inasmuch as that cytokine is known to stimulate thrombopoiesis and is often elevated in both pleural fluid and serum in individuals with MM.34 As expected, an excess of thrombotic events is associated with MM-related thrombocythemia.30

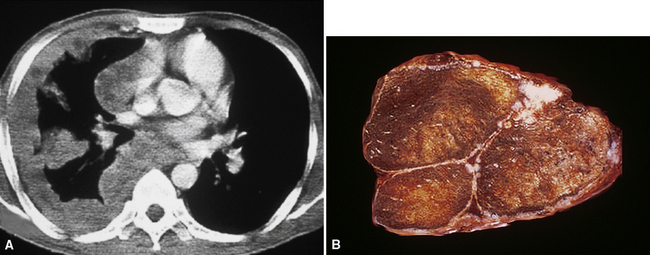

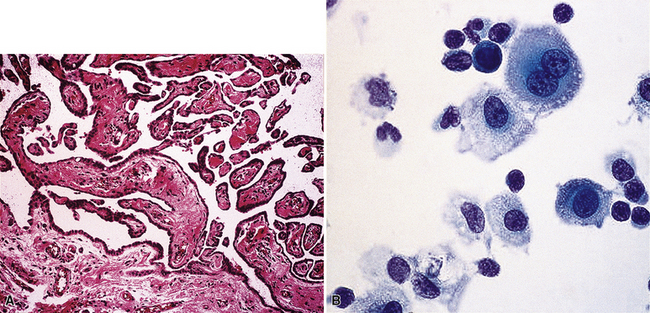

It must be emphasized that none of the clinical findings just mentioned is specific for MM and may also be encountered in connection with other primary pleural neoplasms or metastases to the pleura. In particular, the peculiar form of lung cancer known as pseudomesotheliomatous (pleurotropic) adenocarcinoma (see Chapter 16) is capable of reproducing the symptomatic and radiographic constellation of abnormalities associated with mesothelioma34–38 (Fig. 20-3).

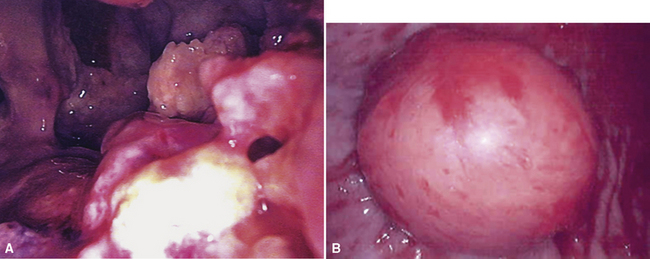

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is now the preferred method for obtaining diagnostic pleural tissue.39–41 VATS (Fig. 20-4) is superior to cytologic sampling of pleural fluid and closed-needle biopsies because of its much greater yield. VATS also produces a specimen of sufficient size for visualization of microarchitectural landmarks. In addition, the morbidity associated with this method is very low. Finally, cytologic examination of pleural fluid in VATS produces positive results in only a minority of cases. This may be because the free surfaces of MMs may be coated with a layer of fibrinoinflammatory exudate, possibly with a misleading benign mesothelial reaction. This process may “wall off” the tumor cells and prevent them from shedding freely into the pleural fluid.42,43

One unwanted but well-reported complication of thoracic biopsies in MM is the growth of tumor along needle or instrumentation tracks in the chest wall.44,45 The reason for this peculiar behavior is currently unknown.

In general, once the clinical presence of diffuse pleural MM has been established, ensuing survival is limited. Most patients live roughly 1 year after diagnosis, regardless of the therapeutic intervention used.46–49 However, a small minority of individuals with good overall performance status and limited intrathoracic disease may be candidates for extrapleural pneumonectomy.49,50 This procedure has resulted in lengthened median survival in some published series50; however, a significant proportion of patients go on to demonstrate the presence of distant metastases of MM under such circumstances, perhaps because of this shift in the natural history of the tumor. Radiotherapy has also been given after extrapleural pneumonectomy, especially for the attempted salvage of patients with recurrent tumor.49 Nevertheless, along with most chemotherapeutic approaches and immunomodulation,51 this treatment modality has not produced uniformly encouraging results. An epithelial histologic subtype, a favorable overall performance score, relatively young age, and the absence of chest pain are all correlated with better survival.18

A more favorable prognosis is also associated with localized malignant pleural mesothelioma, a rare lesion.52–54 It often grows preferentially into the soft tissue of the chest wall rather than along the pleural surface and, thus, presents itself as a discrete mass. Radical surgical removal of localized mesothelioma results in long-term survival in up to 50% of cases.54

Etiologic Considerations in Pleural Mesothelioma

However, the nearly ubiquitous involvement of attorneys in mesothelioma cases, as part of the burgeoning field known as “toxic tort” law,55 has compelled physicians to acquire a working familiarity with the pathogenetic underpinnings of MM. Because of this reality, a brief review of that subject will be provided here; additional information is presented in Chapter 9, which deals specifically with pneumoconioses.

In the early- to mid-1960s, a causal connection between high-level inhalation of amphibole-class asbestos fibers and mesothelioma was first established to the satisfaction of the medical community at large, through the efforts of Wagner and colleagues and others.56–59 At first, epidemiologic surveys were the principal tools whereby this association was identified. However, this avenue of investigation, in which exposures are ascertained primarily by word-of-mouth information, is applicable to patient groups rather than individuals. In the current social environment of the 21st century, epidemiologic questioning and medical history taking are plagued by significant problems in trying to determine the causation of any given case of MM. This is true because media-related exposure of the potential linkage between mesothelioma and asbestos has been robust. Therefore, patients with MM are inculcated with the belief that they must have been exposed to asbestos somewhere and somehow in the past. Moreover, another very real issue concerning the pathogenesis of MM is whether chrysotile-type asbestos—the most commonly used representative of the mineral group in the past several decades—is effective as a carcinogen in this specific context. Aggregated data suggest that chrysotile has very weak mesothelioma genesis.60–63 Hence, asbestos exposure as a generic term has an indefinite and imprecise meaning for individual patients in the absence of other data.64

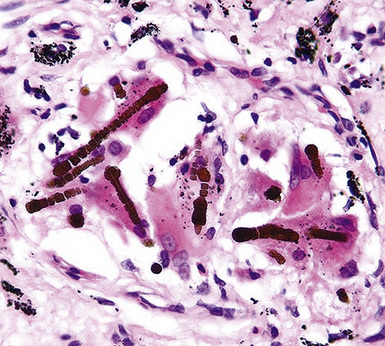

Fortunately, objective information is available to address this area of causation. This is important not only for the legal system—where it can be used to provide concrete fact instead of hearsay—but also for physicians who are committed to the principles of evidence-based medicine. Examination of pathologic specimens continues to be a linchpin in this setting. If conventional light microscopic scrutiny of sections of lung parenchyma demonstrates asbestos bodies at an above-background density (Fig. 20-5), or these structures are seen in intrathoracic lymph nodes, it may be concluded that a mesothelioma in the same case is indeed asbestos-related. Similarly, the radiographic or pathologic presence of pleural plaques, pleural calcifications, or rounded atelectasis (Fig. 20-6) serves a comparable purpose.65–67 Ultimately, the most direct and best approach to evaluating the presence of asbestos in lung tissue is to perform a digestion analysis of representative parenchymal samples (Fig. 20-7), comparing the density of asbestos fibers found by such methods to that which is present in a carefully assembled age-matched and sex-matched control population, acquired from the same geographic region as that in which the patient lived.68

Using the last of these techniques, Roggli and associates have shown that a bimodal distribution of pulmonary asbestos burdens is associated with pleural MMs.69 The majority of patients (group I) have a density of asbestos bodies above 20 per gram of wet lung tissue. The remaining patients (group II) manifest an asbestos burden identical to that seen in appropriate reference cohorts. These data strongly support the conclusion that group II MMs are not etiologically related to asbestos, and, in the absence of other potential causes (see later discussion), these cases are properly termed “idiopathic” or “spontaneous” mesotheliomas. Practically speaking, one can use the latter designation if no objective support for asbestos causation is apparent in a case in question, based on a review of thoracic imaging studies, pleuropulmonary tissue biopsies, or autopsy specimens of lung and pleura.70

The proportion of MMs that is idiopathic in nature has varied from study to study in the published literature, probably as a function of geographic and chronologic bias.71 Cited percentages have generally been between 25% and 40% of all pleural mesotheliomas.72 In our experience in recent years, using the objective approach just outlined, approximately 40% of MMs are spontaneous neoplasms with no definable etiologic linkage to asbestos.

Pleural mesotheliomas that are caused by asbestos develop after a long latency period, typically longer than 20 years in duration.73 The reason for this hiatus is not clear, but it appears that the carcinogenic effect of this mineral group requires a prolonged time—and probably a complicated set of intermediate cellular events74–76—to become manifest. Attanoos and coworkers77 have described a remarkable group of nine asbestos-related mesothelioma cases (eight of which concerned pleural tumors) in which a second concurrent malignancy was present as well. Six of the patients had bronchogenic carcinomas—accompanied by pulmonary asbestosis in five—and the remaining individuals had colorectal, breast, and pancreatic carcinomas. The nine patients in that series represented 1.8% of all mesothelioma cases seen at our institutions.

Other documented etiologies for pleural MM besides asbestos undeniably exist.70,71,78,79 These include prior therapeutic irradiation to the anatomic region in which the mesothelioma develops80–85; chronic serosal inflammation, such as that associated with tuberculosis, pleural empyema, familial Mediterranean fever, or chronic collagen vascular diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or lupus erythematosus)86–89; membership in familial cancer kindreds (“Lynch families”)12,13,90; prior administration of thorium dioxide (Thorotrast), a radiologic imaging agent91,92; and inhalational exposure to erionite, another mineral group.93,94 Infection with Simian virus-40 has recently been examined as another possible cause of human mesothelioma, with contradictory, but usually negative, conclusions.95–100

Interestingly, mesothelioma is a well-documented malignancy of cattle and other animals (both wild and domesticated), and the clinicopathologic attributes of such animal tumors are comparable in every way to those of spontaneous human MMs.101–107 Further attention to the potential pathogeneses of veterinary mesotheliomas could possibly be illuminating in a mechanistic sense.

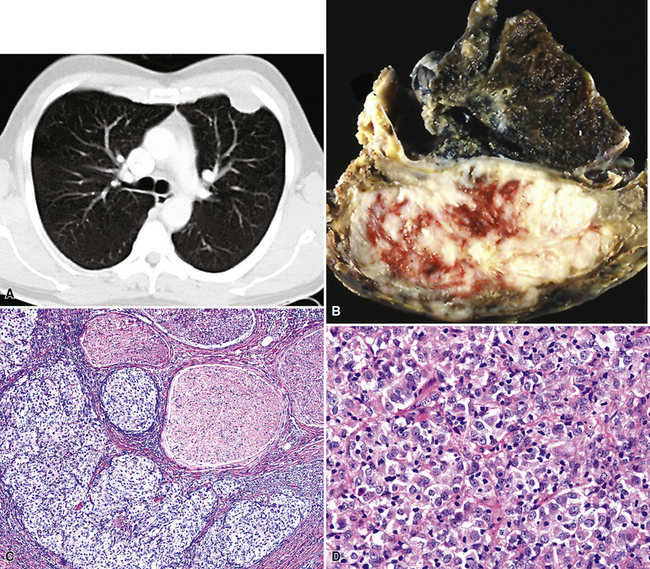

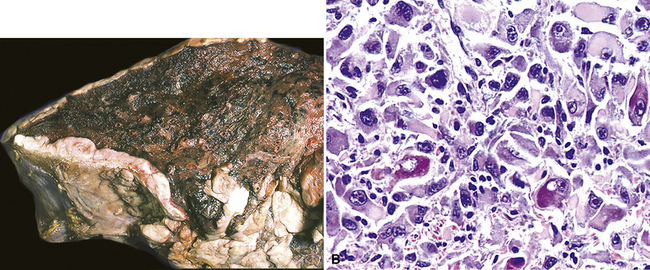

Gross Features of Pleural Mesothelioma

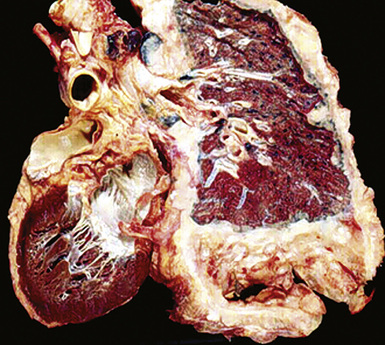

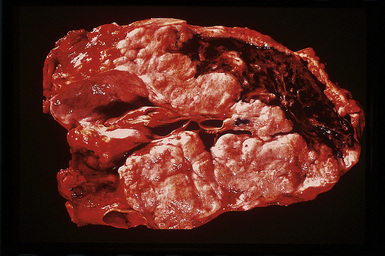

However, more typically, clinical abnormalities are accompanied by multifocal “studding” of the visceral or parietal pleural surfaces, or both, by firm white-gray nodules that individually measure up to several centimeters in diameter. With time, these become innumerable and confluent, obliterating the pleural cavity and often forming a thick layer of constricting neoplastic tissue (Figs. 20-8 and 20-9). Invasion of contiguous structures, including the peripheral lung parenchyma, pericardium and myocardium, adventitia of the great thoracic blood vessels, and soft tissue of the chest wall, is common as tumor growth advances. In addition, mesotheliomas of the pleura may cross the central apertures of the diaphragm to secondarily involve the peritoneal cavity,108 and they are also capable of crossing the mediastinum to involve the contralateral hemithorax. If the patient survives long enough, the terminal image of the tumor may be that of a dense rind of tissue that encases the viscera of the chest.109 Grossly visible metastases in regional lymph nodes and distant sites may also be appreciated, but they generally appear only late in the clinical course. It should be noted that there is nothing specific about the macroscopic characteristics just outlined. They are potentially common to MM, metastatic carcinoma in the pleural spaces, pleural lymphoma, and primary pleural sarcomas.34–36,110,111

Solitary (localized) MMs of the pleura most often grow exophytically into the soft tissue of the chest (Fig. 20-10) or, alternatively, into the subjacent lung parenchyma, rather than spreading along the serosal surfaces.54,112 As such, they can macroscopically simulate peripheral carcinomas of the lung.

Cytopathologic Features of Pleural Mesothelioma

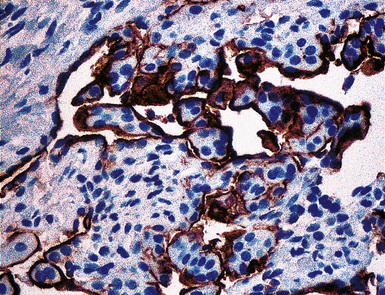

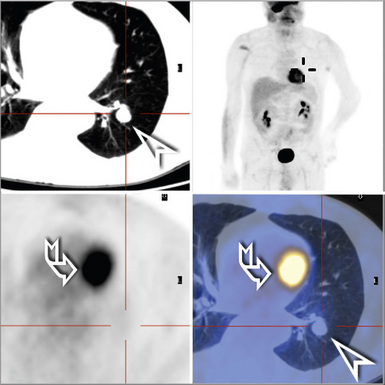

Mesothelial proliferations in the pleura have a wide spectrum of potential cytomorphologic appearances and can rightfully be included in several generic cytologic categories that encompass small round cell tumors, polygonal cell malignancies, spindle cell and pleomorphic lesions, and neoplasms with mixed cellular features.113 However, traditionally, three broad histopathologic patterns of mesothelioma have been considered: epithelial (including tubulopapillary, oncocytoid/deciduoid, clear cell, and small cell subtypes), sarcomatoid (including desmoplastic and “lymphohistiocytoid” variants), and biphasic. These lesions may, on occasion, show other unusual histopathologic features, such as the presence of extensive myxoid change, “glomeruloid” features, adenomatoid tumor-like images, “rhabdoid” features, and metaplastic formation of bone and cartilage.

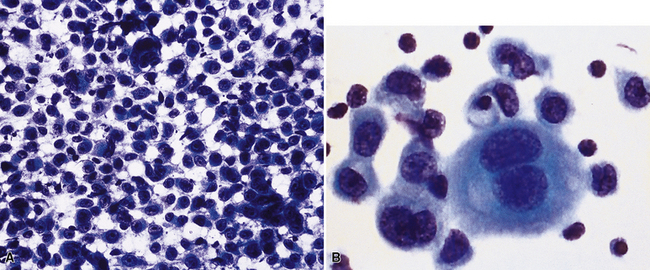

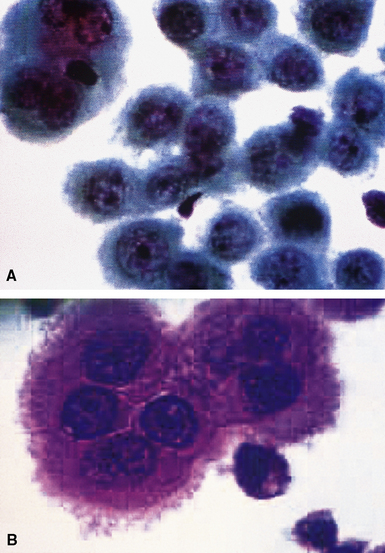

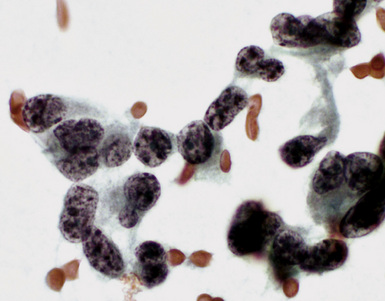

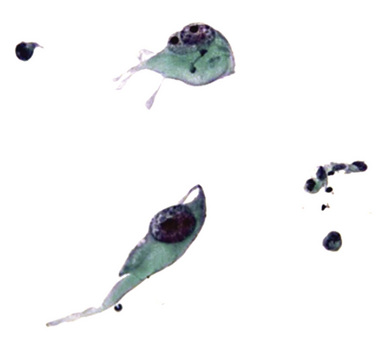

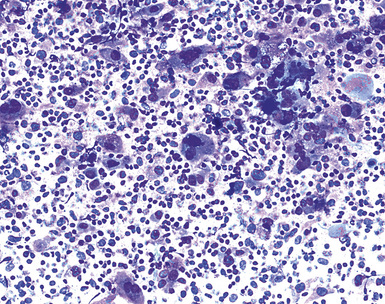

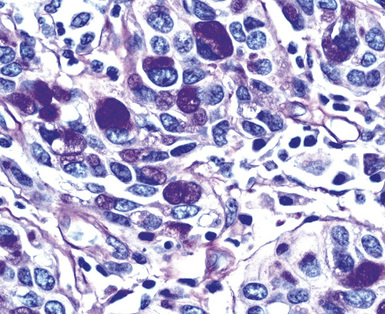

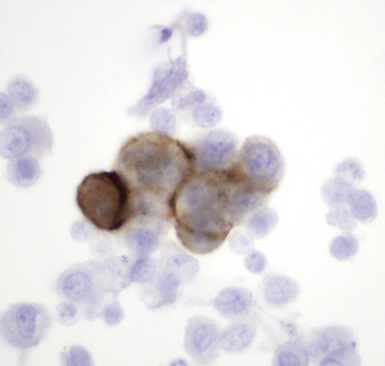

Epithelial mesothelioma is composed of sheets and clusters of variably atypical epithelioid cells in effusion cytology specimens. Such samples are typically densely cellular (Fig 20-11). Mitotic figures and background necrosis are uncommon, but these two features may certainly be apparent in high-grade lesions. Epithelial MMs may also show papillary or tubular cell groups (Fig. 20-12), and, in thoracentesis specimens, the malignant cells may be surprisingly bland cytologically.114–119 Conversely, benign reactive mesothelia can show an alarming degree of nuclear atypia, compounding the difficulty of their diagnostic separation from malignancies.116,120 Groups of both reactive and neoplastic mesothelial cells may demonstrate intercellular spaces or “windows,” and sufficient dispersion of such elements shows the presence of fuzzy cell membranes due to the presence of elongated plasmalemmal microvilli (Fig. 20-13). Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios are high in obviously anaplastic MMs, but this finding may not be characteristic of all tumors. Small cell epithelial mesothelioma demonstrates tightly clustered cell groups with scant cytoplasm and no obvious microvilli. It may be exceedingly similar cytomorphologically to other small cell malignant neoplasms, particularly small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma121 (Fig. 20-14).

Figure 20-12 A tubular profile of tumor cells is apparent in this pleural fluid cytology preparation of malignant mesothelioma.

Sarcomatoid mesothelioma contains cytologically malignant dyshesive fusiform cell proliferations that cytologically imitate other tumors of mesenchymal origin (i.e., sarcomas)122 (Fig. 20-15). In pleural effusions, the tumor cells of sarcomatoid MM are few in number if they are present at all, with scant cytoplasm, elongated nuclei, and rare mitotic figures. A subtype of this variant is the desmoplastic mesothelioma, which is characterized histologically by a bland appearance of the spindle cells that are embedded in a hypocellular, abundantly collagenized stroma.123 As one might expect, diagnostic tumor cells from desmoplastic tumors rarely, if ever, are shed into effusions.

In the past, “lymphohistiocytoid” mesothelioma was regarded as a sarcomatoid MM variant,124 but it actually bears more resemblance to lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas of various organs than to true sarcomas.125 In this lesion, one sees syncytia of polyhedral cells with prominent nucleoli, admixed with numerous mature lymphocytes. Biphasic mesotheliomas manifest a combination of the cytomorphologic patterns that are expected in epithelial and sarcomatoid tumors.115

Many pathologists are still reluctant to make a diagnosis of mesothelioma based only on effusion cytology specimens, in light of the pitfalls mentioned above. However, our experience over time has shown that this hesitancy is often unnecessary. If several pleural fluid samples in a given case consistently show dense cellularity, an overwhelming dominance of cells with clearly mesothelial morphologic features, three-dimensional cellular aggregates, and at least some nuclear atypia, a diagnosis of MM is likely. This interpretation can be solidified by preparation of cell block sections (Fig. 20-16) and the application of adjunctive studies.126,127 Therefore, a conclusive opinion can indeed be rendered by the cytopathologist in a sizable proportion of mesothelioma cases.

Kimura and colleagues128 have proposed that a scoring system be applied as an aid in this process. Using a scale with a maximum value of 10, these authors assigned one point to each of the following features, in favor of an ultimate diagnosis of MM: variety of cell size, cytoplasmic cyanophilia with visible microvilli, sheetlike cell arrangement, “mirror ball”–like cell groups, obvious nuclear atypia, and cell cannibalism. Two-point values were assigned to the presence of large acidophilic nucleoli and to multinucleated cells with more than eight nuclei. In an analysis of 22 MMs, with 20 cases of conditions featuring benign mesothelial atypia and 50 examples of metastatic carcinoma, the “Kimura system” was effective at separating mesotheliomas, which had scores of more than five, from the other specified lesions.128

Histopathologic Features of Pleural Mesothelioma

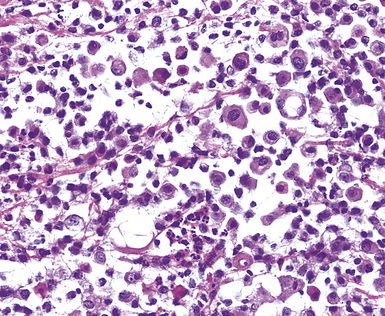

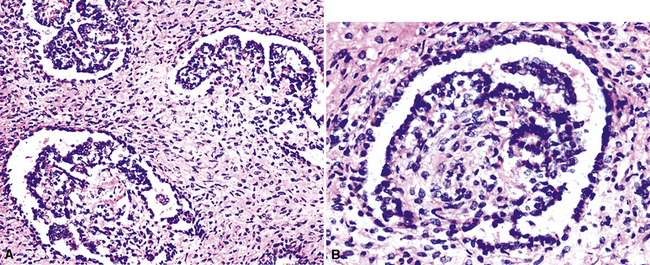

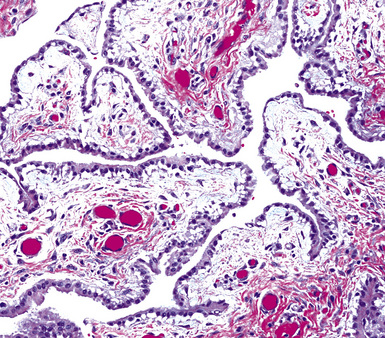

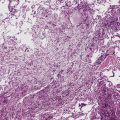

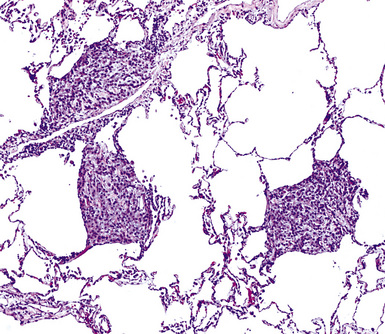

Mesothelioma generally, but not always, spreads multifocally throughout the pleural soft tissues, demonstrating invasion of the peripheral-most subpleural lung tissue in many cases. Other uncommon histologic patterns of growth include129 lymphangitic spread in the lung (Fig. 20-17); pulmonary alveolar permeation through the pores of Kohn, mimicking organizing pneumonia (Fig. 20-18); and lepidic intrapulmonary growth, mantling alveolar septa.

Figure 20-17 Lymphangitic intrapulmonary growth of pleural mesothelioma is seen in this photomicrograph.

There is no substantial difference between the histology of untreated and residual treated mesotheliomas.130

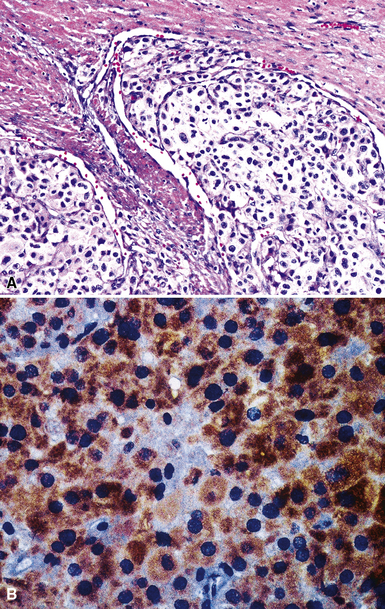

Epithelioid Mesothelioma

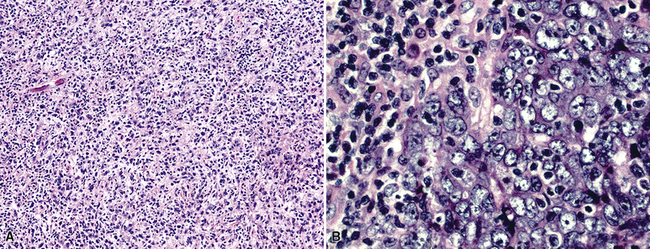

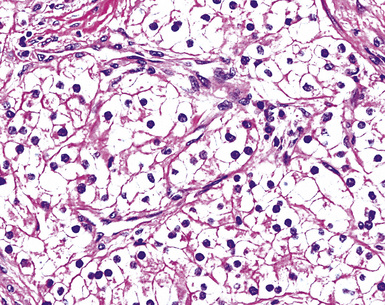

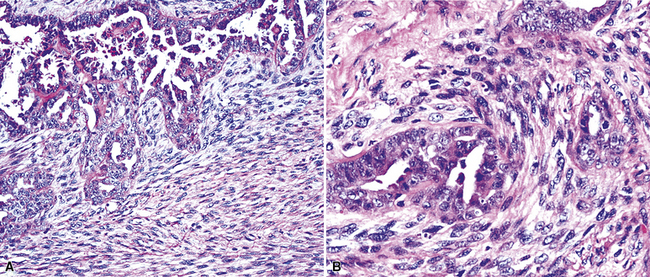

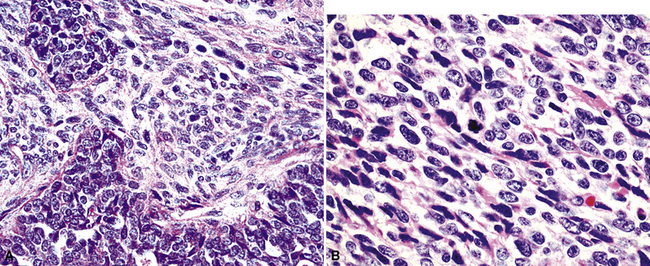

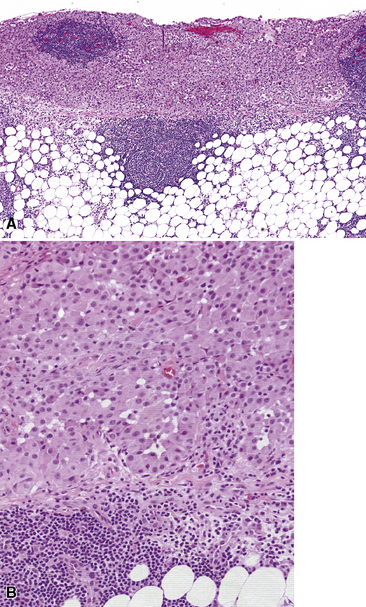

Epithelioid malignant mesothelioma (EMM) is the most commonly encountered microscopic subtype.131 In the majority of cases, the lesion is composed of sheets and nests of polyhedral cells with moderately atypical nuclear features, clear infiltration of the pleural soft tissue or subjacent lung, or both. Lesions comprising uniform expanses of densely apposed polygonal cells are known as “solid” epithelioid MMs (Fig. 20-19). In other tumors, glandlike profiles are common; indeed, some cases demonstrate a predominance of such structures, prompting use of the terms “tubular” or “pseudoglandular” EMM. Micropapillary cell groups are also frequent, and, when they uniformly characterize the lesion, the term “tubulopapillary” MM is rightly applied (Fig. 20-20). This subtype of mesothelioma may be particularly associated with lymphatic invasion and lymph node metastasis.132 Although psammomatous microcalcifications are associated with other epithelial malignancies having a papillary configuration, they are only rarely seen in pleural mesotheliomas.133

Figure 20-19 A and B, “Solid” malignant mesothelioma of the pleura comprising confluent sheets and nests of polygonal tumor cells.

Figure 20-20 A and B, Tubulopapillary malignant pleural mesothelioma demonstrating micropapillary profiles of polyhedral cells.

A useful diagnostic finding in EMM concerns the tinctorial properties of the tumoral stroma. Lightly hematoxylinophilic and myxoid material may be seen between epithelioid cell groups in this lesion, representing the presence of stromal mucin.134 Although it is not specific, this observation does favor an interpretation of MM over one of carcinoma. An extension of the same property is reflected by the cytoplasmic characteristics of some tumor cells in EMM, which demonstrate macrovacuoles having a bluish cast (Fig. 20-21). These probably represent intracellular inclusions of the same stromal material.

“Lymphohistiocytoid” mesothelioma has been mentioned earlier. To recapitulate, it has a histologic appearance that is markedly similar to that of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (Fig. 20-22).

One subtype of EMM has been called “deciduoid” mesothelioma because of the impression that its constituent cells resemble those of decidua in the female genital tract.135–137 As such, they assume a large polygonal cell image with relatively abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and oval vesicular nuclei. This relatively bland appearance belies the invasive nature of deciduoid MM, the biologic features of which are comparable to those of other forms of mesothelioma. Synonyms for this variant are “oxyphilic” or “oncocytoid” MM.101

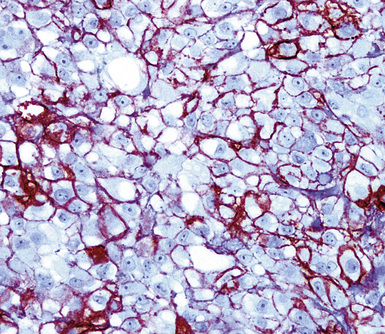

Another form of EMM contains polyhedral cells with strikingly lucent cytoplasm and is accordingly known as “clear cell” mesothelioma138–140 (Fig. 20-23). This variant is extremely uncommon, at least in pure form, and is also related to “foam cell” or “lipid-rich” MM.125

Rarely, foci in EMM may simulate the microscopic appearance of pleural adenomatoid tumors (see Chapter 19), with bland microcystic glandlike profiles composed of compact epithelioid cells.141 However, other areas in those lesions typically have the conventional image of ordinary mesothelioma.

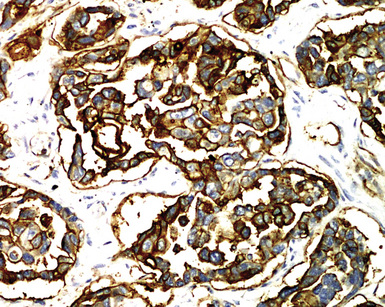

“Glomeruloid” mesothelioma is a relatively recently described variant in which the tumor cells form peculiar arrays that resemble glomeruli in the renal cortex (Fig. 20-24).142 Again, its behavioral properties are no different than those of ordinary EMMs.

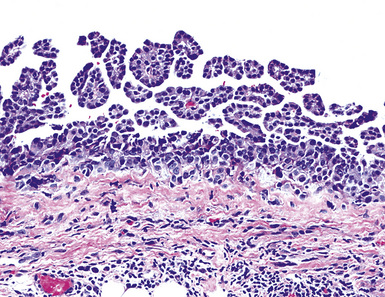

Mention must also be made here of the concept of mesothelioma in situ. This term has been applied to cytologically atypical proliferations of epithelioid mesothelial cells that are confined to the pleural surface, with no evidence of invasion across its basement membrane143,144 (Fig. 20-25). Reports on this finding have been limited to cases where other areas of the pleura did demonstrate infiltrative MM. Hence, it is still not clear as to whether pleural mesothelioma can truly exist in an exclusively in situ form. In fact, we have never seen an autopsy case that involved this finding.

Sarcomatoid (Spindle Cell) Mesothelioma

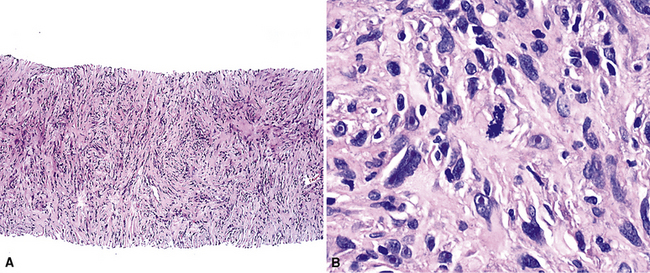

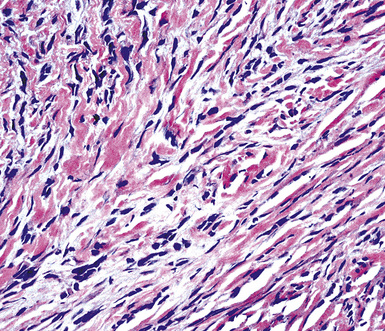

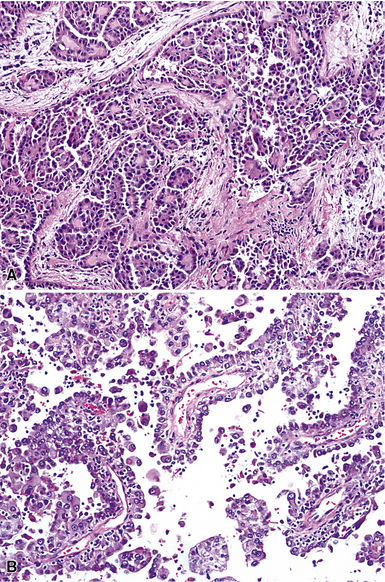

Sarcomatoid malignant mesothelioma (SMM) (also see Chapter 14) is comprised of fusiform cells with variable degrees of atypia and pleomorphism.122,131,145–147 These may be arranged in fascicles, storiform arrays, or random configurations (Figs. 20-26 and 20-27). Tumoral collagen synthesis is likewise heterogeneous. The prevalence of mitotic activity and necrosis in such lesions generally parallels their histologic grade. A special variant of SMM is that which shows divergent differentiation into “heterologous” mesenchymal tissues such as osteoid, cartilage, and striated muscle (Fig. 20-28).148–150 It could rightly be called “metaplastic” SMM. Tumors with angiosarcoma-like foci in this category have also been termed “pseudovascular” or “angiomatoid” mesotheliomas (Fig. 20-29). Klebe and associates have suggested that all pleural neoplasms with purely sarcomatous features should be classified as mesotheliomas, even if they are immunohistologically negative for keratin.151 We cannot agree with that conclusion, because, as discussed subsequently, their experience is that SMMs express keratin in virtually every case regardless of morphologic nuances.

Figure 20-28 A and B, Divergent osteochondroid differentiation in sarcomatoid malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Figure 20-29 A histologic resemblance to angiosarcoma is seen in this “pseudovascular” mesothelioma.

Myxoid stroma may also dominate the microscopic picture in occasional examples of SMMs. When cellular atypia in sarcomatoid mesothelioma is extreme, the designations “anaplastic” or “pleomorphic” MM are appropriate.152

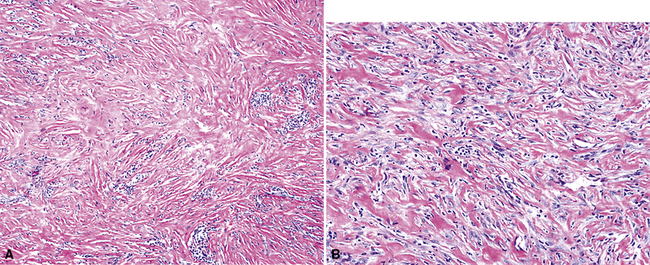

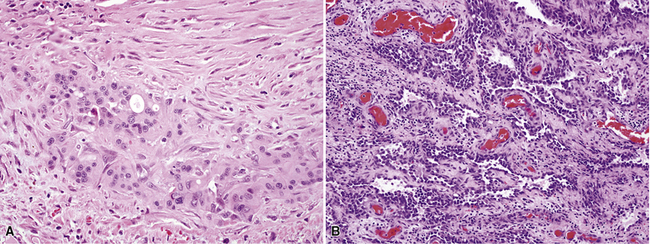

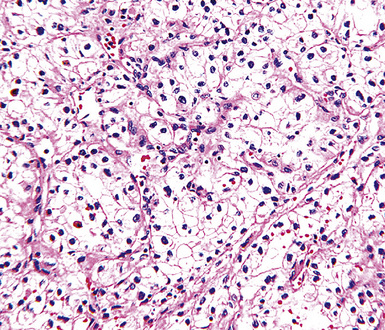

Desmoplastic Mesothelioma

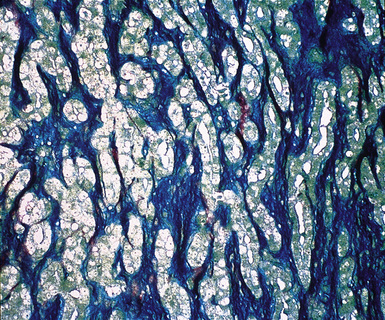

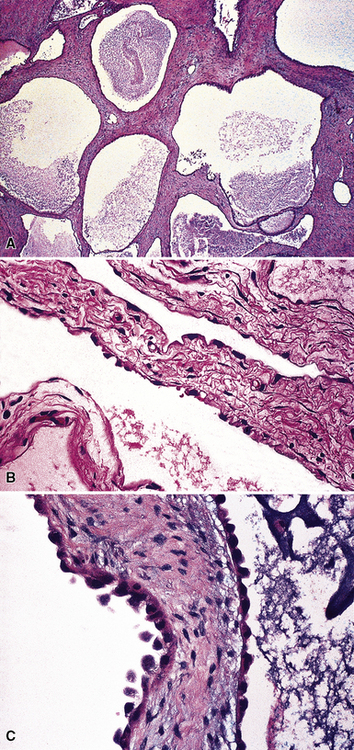

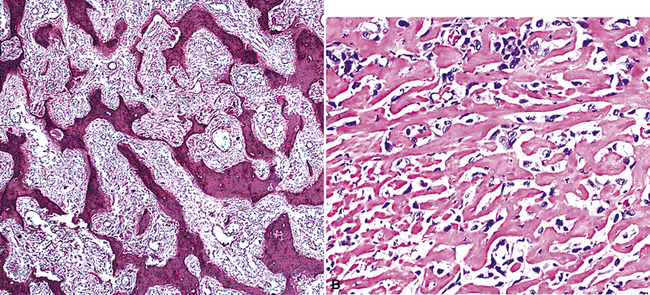

As mentioned earlier, desmoplastic malignant mesothelioma (DMM) is a special subtype of SMM in which spindle-shaped or stellate neoplastic cells are bland cytologically and have a low density per unit area.123,153–155 They are set in a markedly collagenized and hyalinized stromal matrix, often with a “basket weave” configuration like that of pleural plaques or fibrohyaline pleuritis (fibrous pleurisy)123 (Fig. 20-30). Mitoses are sparse, and necrosis is limited if it is present at all. The World Health Organization recommends that the designation DMM be used when more than 50% of the tumor shows this pattern. Many SMMs and some biphasic tumors (see later discussion) also contain small foci in which a desmoplastic foci can be seen; in such cases mention of such foci is recommended, because this variant has a particularly poor prognosis.

The malignant nature of DMM is manifested by its invasion of underlying lung or adjacent soft tissues156 (Fig. 20-31). In addition, careful scrutiny of the tumor usually (but not always) reveals a level of cellular atypism and a degree of cellular density that exceeds that of benign pleural lesions (Fig. 20-32). Moreover, there is no microscopic “zonation” in DMM. That phenomenon is best represented in fibrohyaline pleuritis, in which lesional cellularity decreases as one moves spatially from the pleural space into the subjacent tissues.157 The Verhoeff-Van Gieson elastic stain is helpful in the differential diagnosis of fibrohyaline pleuritis versus DMM. Mesotheliomas show a paucity of internal elastic fibers, or, if they are present, there is no regularity of their orientation. In contrast, fibrous pleuritis usually exhibits a retention of laminated, roughly parallel elastic tissue throughout the thickened visceral pleura (see Chapter 18).

Biphasic Mesothelioma

As their name suggests, biphasic malignant mesotheliomas are typified by admixtures of two morphologic configurations, usually at least one variant of EMM and at least one in the spectrum of SMM. Those components may be abruptly juxtaposed to one another or blend imperceptibly131 (Fig. 20-33). Schramm and coworkers have suggested that biphasic malignant mesotheliomas typify the “epithelial-mesenchymal” transition that can be seen in several tumor types, and that this phenomenon worsens the behavior of epithelial neoplasms.158

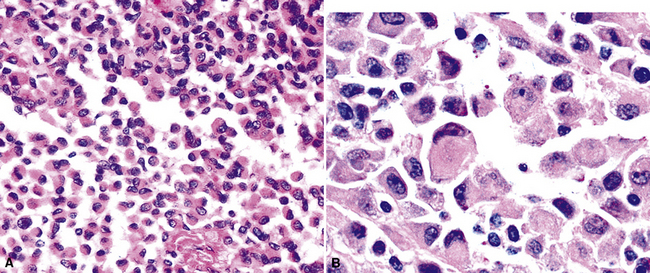

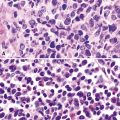

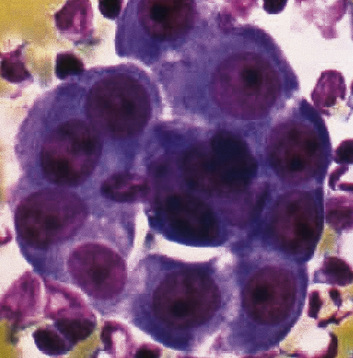

Small Cell Mesothelioma

Another uncommon type of MM is its small cell form, a variant of epithelial MM.121,159 It is only rarely seen in “pure” form and usually includes a portion of tumors with other histologic patterns. This lesion is composed of compact round cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, oval nuclei with dispersed chromatin, variably discernible nucleoli, and scant amphophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 20-34). As such, it is morphologically similar to several other malignant small cell/basaloid neoplasms, including basaloid carcinoma, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell melanoma, small round cell sarcomas, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Rhabdoid Mesothelioma

Over the past decade, it has become apparent that a relatively broad spectrum of malignant tumors may exhibit a “rhabdoid” phenotype, akin to that seen in high-grade pediatric renal neoplasms. Extrarenal rhabdoid tumors (ERTs) may be “pure” histologically, or they may represent a new clonal element that has arisen from another recognizable tumor type.160 Hence, one may see ERTs in combination with a definable carcinoma, melanoma, or sarcoma. In the latter instance, the term “composite” ERT is apropos. MMs are no exception to these precepts. Thus, wholly rhabdoid MMs may be encountered in some cases, whereas other pleural mesotheliomas may show an “ordinary” morphotype that is admixed with ERTs.161,162

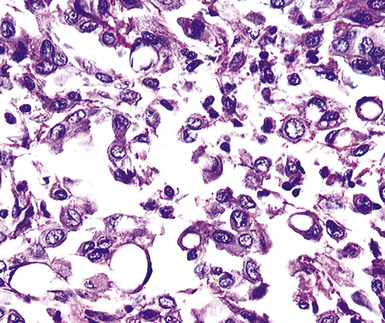

Rhabdoid cells are characterized by a moderately pleomorphic epithelioid shape, eccentric nuclei with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli, and distinctive eosinophilic cytoplasm having a hard globular quality (Fig. 20-35). They are relatively dyshesive; occasional spindle cell change and multinucleation may be seen as well.

Classic rhabdoid tumors of the kidney and nervous systems show consistent loss of the intranuclear INI1 gene product, which functions as a tumor suppressor.163 However, composite rhabdoid lesions generally retain it. To date, no published studies have addressed the INI1 status of rhabdoid MM.

The principal significance of a rhabdoid phenotype is the biologic aggressiveness with which it is associated, regardless of other clinicopathologic details of the individual tumor.160,162 Nonetheless, because mesotheliomas as a group have such an adverse outcome, the behavioral impact of rhabdoid change is not as great in this particular context.

Localized (Solitary) Mesothelioma

Localized MM of the pleura is defined by its gross characteristics rather than its microscopic ones. This tumor can show any of the histologic patterns considered previously (i.e., epithelioid, biphasic, sarcomatoid, and variations thereof).54,112,164,165 In contrast to diffuse pleural mesotheliomas, an increasingly spindle cell composition does not appear to affect the prognosis of people with localized MMs negatively.112,166 Insufficient numbers of these MMs have been analyzed to say with any certainty that they may be causally related to above-background asbestos exposures.

Histochemical Features of Pleural Mesothelioma

Up until 20 years ago, the separation of MMs from other histologically similar neoplasms was based largely on histochemical results. The capacity for adenocarcinomas to synthesize epithelial mucin (Fig. 20-36) had been recognized quickly after the application of specialized biochemical methods in surgical pathology, and it was soon recognized that mesotheliomas did not possess this ability.167–174 Conversely, MMs were found to manufacture stromal mucin, which was labeled by the colloidal iron or Alcian blue methods at pH 2.5, and prior treatment of tissue sections with hyaluronidase removed this substance167,170,173,175 (Fig. 20-37). Thus, these observations set the stage for the use of the periodic acid/Schiff technique, with and without diastase predigestion (to remove glycogen, which, like epithelial mucin, is positive for periodic acid/Schiff); the mucicarmine method (to label epithelial mucin); and the colloidal iron or Alcian blue procedures, with and without hyaluronidase pretreatment, for the histochemical delineation of adenocarcinomas and mesotheliomas.

Providing that one observes the cautions just cited, epithelioid mesotheliomas can be distinguished from carcinomas histochemically in approximately 50% of cases.149 The periodic acid/Schiff–diastase technique is the most useful for that purpose, because, at least, in our experience, it is more sensitive than the mucicarmine (Best) stain. Moreover, there have been sporadic reports of MMs that were spuriously labeled with the mucicarmine procedure, apparently because it unexpectedly recognized a form of stromal mucin.176 Pretreatment with hyaluronidase is successful in abrogating that aberrant reactivity, and therefore it should be used routinely if mucicarmine is utilized in differential diagnoses that include epithelioid MM.

In the same vein, colloidal iron and Alcian blue methods commonly label epithelial as well as stromal mucins. Hence, only those epithelioid lesions that lose their colloidal iron/Alcian blue positivity after hyaluronidase predigestion are consistent with mesothelial neoplasms.167,169–171 Again, roughly 50% of polygonal cell MMs manifest this pattern of reactivity.

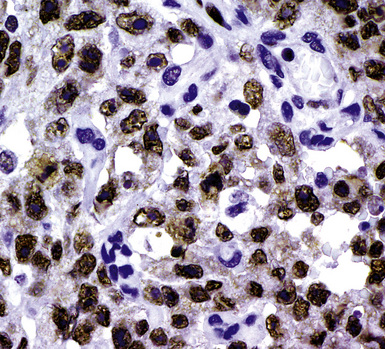

During the 1980s, it was recognized that silver impregnation methods were able to label accumulations of intranuclear proteins that are associated with active transcription of nucleic acid. The silver-positive argyrophilic nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs, or silver-stained nucleolar organizing regions) are now known to be related to double chromosomal “satellites,” chromosome polymorphisms, and structural abnormalities involving chromosomal satellite regions.177–179 Silver nitrate (in colloidal suspension) has an affinity for them, yielding a black precipitate, and discrete globular deposits of it are then visible in positive nuclei on conventional microscopy. The number of AgNORs seen in this way appears to parallel the density of quantitative markers of nucleolar protein synthesis, such as fibrillarin180 (Fig. 20-38). Several authors have confirmed the fact that MMs and carcinomas both have higher AgNOR counts per nucleus than do reactive mesothelial proliferations.181–183 Therefore, the usual application of this method is not to separate mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma but to distinguish MM from an atypical but benign mesothelial proliferation.181,182 AgNOR values in those two groups have ranged from slightly greater than 1 in minimally atypical benign mesothelial cells to greater than 7.5 in highly anaplastic mesothelioma cells, usually showing a bimodal distribution in mesotheliosis and MM.184 Despite the hopeful nature of these results, substantial numerical overlap still exists between the two lesional groups in question. Some have successfully used these results in combination with immunohistochemistry, image cytometry, and in situ hybridization assessment of chromosome 9p21 deletions to allow for greater than 95% accurate separation of reactive from neoplastic mesothelial proliferations.185,186

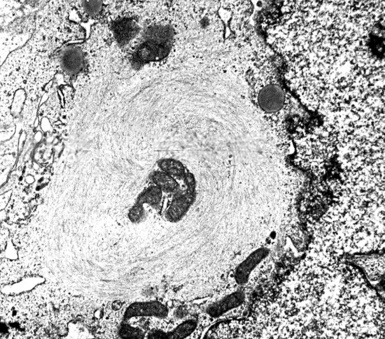

Electron Microscopic Features of Pleural Mesothelioma

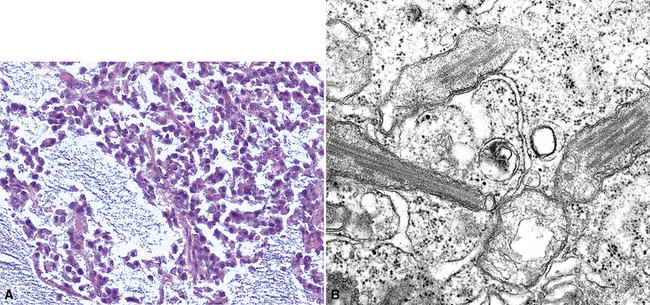

In the early 1970s, several investigators began to catalog the ultrastructural characteristics of MM and compare them with those of histologically similar neoplasms.187–189 Through the ensuing years, it has become apparent that transmission electron microscopy is an extremely effective tool in the delineation of mesothelial differentiation. In addition, it provides valuable information in the differential diagnosis of other malignancies.190,191

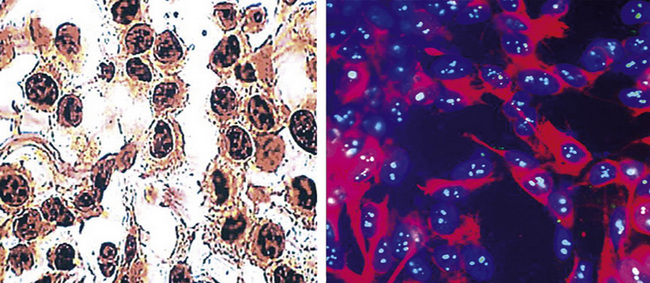

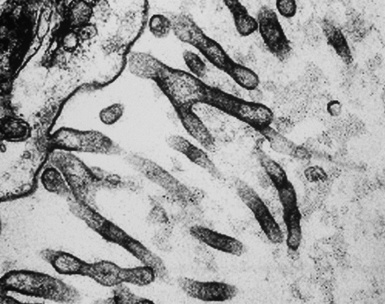

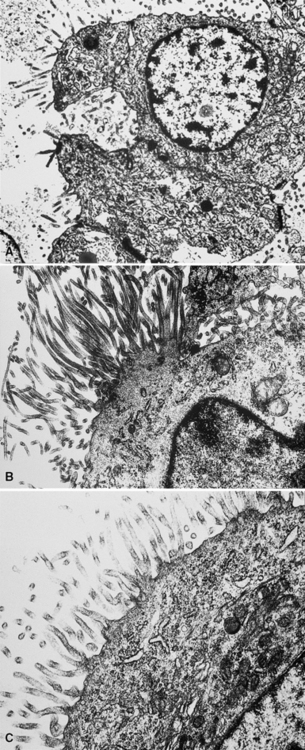

In epithelioid mesotheliomas, a constellation of findings that includes abundant tangles of cytoplasmic intermediate filaments, with focal formation of perinuclear tonofibrils; elongated and complex desmosomes (Fig. 20-39); an absence of mucin droplets; and the presence of long, branching, plasmalemmal microvilli (with a length-to-diameter ratio of 10:1 or more)190–194 (Fig. 20-40) is typical. Other common findings include cytoplasmic glycogen deposits, dilated intercellular spaces, and intracellular lumina, which are also often lined by microvilli. External microvillous projections are sometimes difficult to evaluate with regard to their dimensions, because they can be compressed and distorted when caught between adjacent tumor cells. Basal laminae are also present around many of the neoplastic cells in mesotheliomas, and the microvilli are often coated by an amorphous granular material195,196 (Fig. 20-41).

Figure 20-40 A to C, Elongated and “bushy” plasmalemmal microvilli are seen in these epithelioid mesotheliomas ultrastructurally.

Relatively few neoplasms show all of the “classic” characteristics of MM,195 but most mesothelial tumors manifest enough of them to make their identification straightforward. In contrast, metastatic adenocarcinomas (MACs) of various anatomic origins, which represent the principal diagnostic alternative to MM, exhibit short truncated microvilli and an absence of tonofibrils and may contain intracytoplasmic mucin granules as well.190,197–199 Wick and colleagues174 performed a comparative study of electron microscopy and immunohistology in the distinction between EMMs and MACs, and they found the two techniques to be comparable in efficacy.

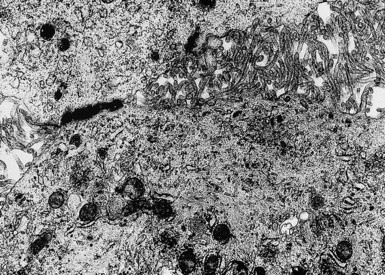

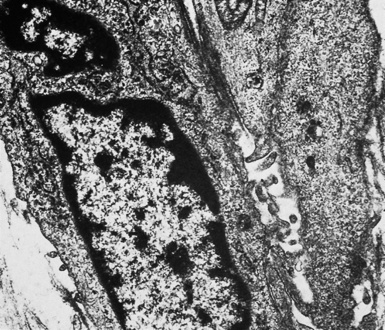

On the other hand, SMMs lose the distinctive plasmalemmal modifications that characterize their epithelioid counterparts. Spindle cell and pleomorphic mesotheliomas most closely resemble true sarcomas at an ultrastructural level (Fig. 20-42), except for the presence of rare intercellular junctional complexes and intermediate filament bundles.122,193,200,201 In that specific context, electron microscopic assessment is not definitive diagnostically.

Some authors have suggested that ultrastructural studies no longer add substantively to the diagnosis of MM.202 However, other authors203,204 (and those of this chapter) do not agree.

Immunohistochemical Findings in Pleural Mesothelioma

Among these problems, the one that is most commonly encountered is that of mesothelioma versus metastatic carcinoma. Despite the more uncommon nature of SMM, immunohistochemistry is nonetheless equally useful in its distinction from true sarcomas affecting the pleural space. However, in the remaining settings, in which the differential diagnosis involves a benign or reactive condition, the practical contribution of immunophenotyping is much more limited. With specific reference to desmoplastic mesothelioma, it has been properly suggested that because of its poor prognosis and the lack of effective treatment, underdiagnosis of that tumor is preferable to overdiagnosis.153 It may well take several biopsies to establish a definitive interpretation in such cases.

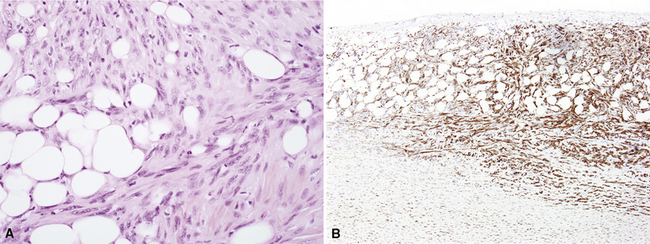

Each of the previously cited diagnostic questions is associated with differing panels of immunohistochemical reagents. For instance, in cases of possible spindle cell or desmoplastic mesothelioma, immunohistologic evaluation should principally focus on whether the tumor is keratin-positive. Calretinin, Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) gene product, and podoplanin have much lower rates of reactivity in SMMs compared with epithelioid and biphasic variants. Other markers, such as desmin, muscle-specific actin, and S-100 protein, are necessary only to subtype a mesenchymal neoplasm if the keratin reaction is negative. In the morphologic context of sarcoma-like tumors, the application of antibodies that are used to recognize overtly epithelial tumors (e.g., Ber-Ep4, CD15, cancer antigen 72-4 [CA 72-4], and carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA]) is illogical, because neither sarcomas nor sarcomatoid carcinomas synthesize the targets of these reagents.205 The following sections will review the different analytes that have been tested clinically in the study of MM, to provide a guide for a practical approach to immunohistochemical analysis.

Antibodies Often Used in the Analysis of Possible Mesothelioma

General and Exclusionary Markers

Keratins

Keratin antibodies have been extensively applied to MMs and their simulators, with the principal goal of distinguishing mesothelioma from adenocarcinomas206–211 and true sarcomas. Some authors have concluded that particular staining patterns for specific keratins may allow for the separation of those tumor types, and differing degrees of contextual specificity and sensitivity have been ascribed to various keratin subsets. In particular, antibodies to keratin 5/6 have been promoted as helpful immunohistochemical markers for MM211 (Fig. 20-43). In one assessment, Ordóñez found that 40 examples of mesothelioma were positive for keratin 5/6, whereas 30 pulmonary adenocarcinomas were negative. However, he also observed focal reactivity in 14 of 93 cases of nonpulmonary adenocarcinoma, to some extent limiting the utility of keratin 5/6 in the exclusion of metastases to the pleura.211 Another study reported 92% keratin 5/6 positivity in MM and 14% labeling in cases of MAC.212 Despite these drawbacks, keratin 5/6 does appear to be a helpful presumptive marker for mesothelioma when used in the proper fashion and the appropriate morphologic setting.

In general, it has been noted that reagents against high-molecular-weight keratins will label most mesotheliomas and relatively few adenocarcinomas, whereas antibodies to low-molecular-weight keratins recognize both of those tumor groups.213 Keratins 7, 8, 18, and 19 are present in all MMs and adenocarcinomas, whereas keratins 5, 6, 14, and 17 are found in some types of mesothelioma but are lacking in MACs.213 The latter four proteins are absent in cases of sarcomatoid mesothelioma.

Our approach to keratin testing in evaluating poorly differentiated malignancies is to use a broadly active mixture of monoclonal antibodies to such proteins. At present, we use a “cocktail” of commercial antibody reagents that targets all of the known keratin subtypes between keratins 1 and 20, mixed together in the same diluent and used with epitope-retrieval techniques.214 The goal of this practice is to detect any keratin, rather than a specific one, because the pragmatic task in virtually all cases is the separation of epithelial from nonepithelial malignant neoplasms. With these remarks as a preface, the sensitivity of keratin “cocktail” staining for all forms of mesothelioma (including SMM) approximates 100% in our hands (Fig. 20-44).

Epithelial Membrane Antigen

Studies dealing with anti–epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) have shown that it commonly yields positive results in both MACs and MMs.215–217 Antibodies to EMA potentially label mesotheliomas of all histologic subtypes. It has been said that this protein generally shows a double-density (“tram track”) cell membranous pattern of staining in MMs (Fig. 20-45), whereas MAC cells demonstrate more delicate membrane labeling.218 Other authors have found that reactive mesothelial hyperplasia is EMA-negative, in contrast with primary malignancies of the serosal surfaces.219 However, both of those claims are open to question220; in practical usage, we have found that the reactivity patterns in question are not universally present as depicted in the literature.

Carcinoembryonic Antigen

CEA has been considered by most observers to be one of the most reliable markers for distinguishing MM from adenocarcinoma.174,221–223 The vast majority of mesotheliomas lack CEA. Positivity for CEA has been reported in up to 5% of cases of MMs, but studies describing that phenomenon have generally used unabsorbed heteroantisera to CEA that undoubtedly recognized unrelated molecules. Monoclonal antibodies to specific CEA epitopes are more reliable in this context, although they are less sensitive for the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and, therefore, less helpful diagnostically. However, the use of anti-CEA reagents has no role in the diagnosis of sarcomatoid mesotheliomas, as mentioned earlier.

Thyroid Transcription Factor-1

Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is a 38-kDa intranuclear polypeptide that is synthesized by a gene located on chromosome 14q13; it is also known as NKX2A protein. 224,225 Among epithelial elements, this homeodomain-containing nuclear transcription factor is restricted to follicular and parafollicular thyroid cells, glandular and alveolar-lining cells of the lung, and anterior pituicytes. TTF-1–positive neoplasms are largely encompassed by those same tissues, with the addition of moderately and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of various organs and the omission of parathyroid and pituitary tumors.224 Approximately 75% to 85% of pulmonary adenocarcinomas and adenosquamous carcinomas are labeled for TTF-1.226,227 In contrast, mesotheliomas of all histologic types have been consistently nonreactive.228 It is important to require that nuclear labeling be regarded as the only true pattern of positivity for TTF-1.229

Napsin-A

Napsin-A is a cytoplasmic aspartic proteinase that plays a role in the synthesis of surfactant protein-B in the lungs. In normal tissues, it is expressed strongly in type 2 pneumocytes. Antibodies to napsin-A have been applied clinically only recently, and the overall number of mesotheliomas and adenocarcinomas studied thus far is relatively small. However, in one evaluation, 85% of pulmonary adenocarcinomas were napsin-A–reactive, compared with no cases of mesothelioma or colonic, pancreatic, or mammary carcinoma.230 Unexpectedly, napsin-A was also observed in clear cell and papillary renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), as well as in tall cell papillary thyroid carcinomas. It appears that this marker may best be used in the narrow differential diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary adenocarcinoma versus EMM.

CD15

CD15 has a high level of specificity for MACs,174,222,223,231–233 but some examples of MM have also shown focal labeling for this marker. This finding appears to be more common in peritoneal tumors than in pleural lesions.234 Like CEA, the use of CD15 is most appropriate in the evaluation of biphasic or epithelial mesotheliomas, because sarcomatoid tumors consistently lack it.

CA 72-4

CA 72-4, which is also known as tumor-associated glycoprotein-72 (recognized by monoclonal antibody B72.3), is a generic epithelial determinant that is a high-molecular-weight cell membranous glycoprotein.234–239 Regardless of their sites of origin, the majority of MACs show strong reactivity for this marker. Rare examples of MM may also show focal or weak labeling.240

Ber-Ep4

Ber-Ep4 is another epithelial marker that was initially thought to be specific for adenocarcinomas,241,242 and it does indeed demonstrate a high level of sensitivity for these neoplasms as a generic group. Nevertheless, it is now known that approximately 15% of mesotheliomas can show focal staining with this antibody,243,244 and it has no value in the evaluation of purely sarcomatoid tumors.

MOC-31

MOC-31 is a monoclonal antibody that labels a 35-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein in the plasmalemma of most glandular cells.245,246 This molecule is closely related to lung cancer–associated antigen-2,247 but, in addition to pulmonary adenocarcinomas, MOC-31 is reactive with glandular malignancies arising in most other organ sites as well.248,249 Mesotheliomas are reproducibly negative for this marker.244,249

BG8

BG8 is a synonym for Lewis blood group antigen Y (Ley; CD174), a glycoprotein that is overrepresented in malignant epithelium and is again widely distributed in glandular cells throughout the body.250–252 Accordingly, its immunohistochemical characteristics in neoplasia generally parallel those of the MOC-31 antigen.228,253

p53

The p53 gene product is a nuclear phosphoprotein that regulates DNA replication, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.254 In cases featuring atypical spindle cell proliferations that are morphologically suspicious for DMM, p53 immunolabeling of greater than 10% of the lesional cells favors a diagnosis of mesothelioma over one of a cellular pleural plaque or fibrohyaline pleuritis.224 Nevertheless, that characteristic is not observed in all DMMs, and all cases of pleuritis are not necessarily p53-negative.

Another salient observation is that mutant p53 proteins, which are generally recognized by immunohistologic studies, are relatively restricted to MMs and are not typically seen in resting or reactive mesothelial cells.255–258 On the face of things, mutant p53 therefore would seem to have potential value in the distinction of cytologically bland MM from mesothelial hyperplasia. Nevertheless, we would suggest avoiding exclusive reliance on p53 under such circumstances based on their clinical experience with this problem. They have seen several examples of undeniably benign mesothelial proliferations that were unexpectedly immunoreactive for p53.

Inclusionary Markers

The aforementioned antibodies include several that have been recommended by the U.S. and Canadian Mesothelioma Panel,173 and they are probably the most commonly used markers in surgical pathology laboratories for the evaluation of malignant pleural neoplasms. However, except for p53, all of the markers presented thus far assist in the diagnosis of MM by exclusion. Over the past several years, efforts have been directed at identifying “proactive” markers of mesothelioma (i.e., those that would be present in the majority of MMs). Some such antibodies have been used diagnostically, whereas others have been analyzed as prognostic indicators. A brief discussion of these reagents follows.

Calretinin

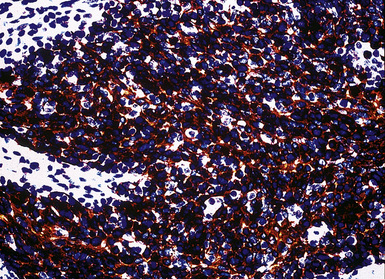

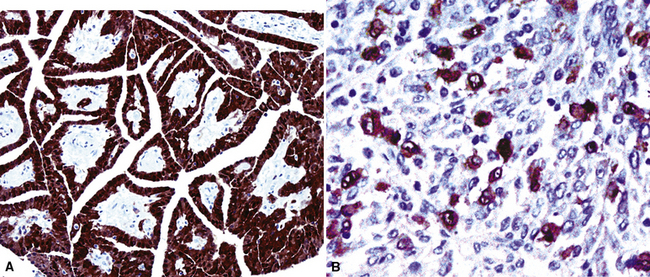

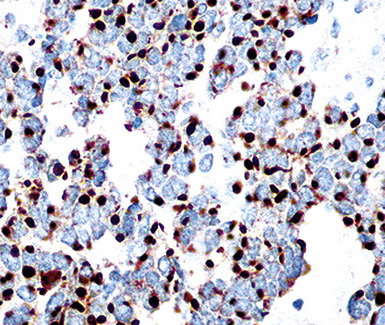

Calretinin is a member of a large family of cytoplasmic calcium-binding proteins.259 This marker is seen in more than 95% of mesothelioma cases of the epithelioid and biphasic types260–262 (Fig. 20-46). Antibodies to other related polypeptides are also available, including antiparvalbumin and anticalbindin, but they fail to recognize mesotheliomas and non-neoplastic mesothelium.263 Interestingly, there are conflicting reports regarding the expression of calretinin in sarcomatoid mesothelioma; some observers have seen universal staining of such neoplasms, but others have claimed that they are negative.264–266 Our experience is that approximately 30% to 40% of sarcomatoid lesions do, in fact, label for calretinin, albeit in a focal fashion. Selected studies have shown that this antibody may also stain some adenocarcinomas,261 but, if one requires nuclear labeling for calretinin as a truly positive result, these are few in number.

WT1 Gene Product

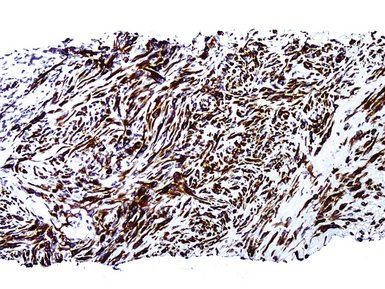

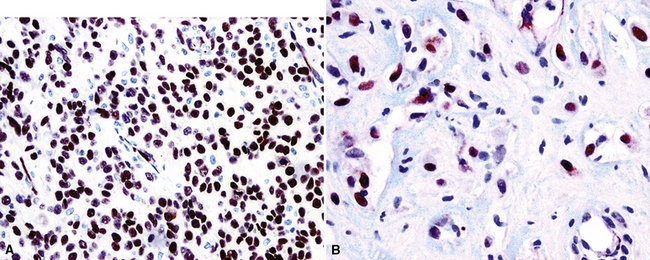

The WT1 gene resides on the short arm of chromosome 11. When it is deleted constitutively, patients have a tendency to develop nephroblastoma, an embryonal renal tumor.267 Because of this association, WT1 has generally been regarded as a tumor-suppressor gene, but it is conversely overexpressed in other malignancies, including mesothelioma, and therefore also may function as an oncogene.268 Nuclear immunolabeling for WT1 gene product is apparent in greater than 80% of epithelioid and biphasic MMs (Fig. 20-47), but sarcomatoid tumors again demonstrate lesser reactivity in approximately 30% of cases.228,244,265,266,269–271 WT1 is not restricted to mesothelial proliferations, and is also present in carcinomas of the thyroid, kidney, ovaries, and endometrium, some of which enter into differential diagnosis with MM.272,273 Because it is typically absent in adenocarcinoma of the lung, WT1 has greatest applicability when this tumor is the principal diagnostic alternative to epithelioid mesothelioma.228 Its use in the analysis of sarcomatoid tumors is complicated by the fact that true sarcomas can also be WT1-positive.274

Figure 20-47 Nuclear immunolabeling for WT1 protein in epithelioid (A) and sarcomatoid (B) mesotheliomas.

In a comparison of two monoclonal antibodies to WT1, clone WT49 and clone 6F-H2, Tsuta and associates275 found that the first reagent demonstrated greater sensitivity for mesothelioma but it also labeled a higher number of nonmesothelial malignancies, including some lung carcinomas and synovial sarcomas.

Thrombomodulin

Thrombomodulin, or CD141, converts thrombin from a procoagulant protease to an anticoagulant.276 It is found in endothelial cells, syncytiotrophoblasts, mesothelia, and various epithelia, principally including squamous and transitional cells.277,278 The majority of MMs (approximately 65%) label for CD141,212,222,244,253,262,279 (Fig. 20-48) as well as squamous cell carcinomas and transitional cell carcinomas.231,249 Fortunately, p63 protein-immunoreactivity can be used to recognize the latter two tumors, because mesotheliomas are p63-negative.280 Glandular malignancies of various origins (including the lung) have also demonstrated unexpected reactivity in some series, and as many as 13% of adenocarcinomas have been positive.261 Epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas and angiosarcomas, which may occasionally enter differential diagnosis with mesothelioma, are also potentially immunoreactive for CD141.281

Podoplanin

Podoplanin, also known as T1-alpha and Aggrus and recognized by monoclonal antibody D2-40, is a mucin-type transmembrane glycoprotein with extensive O-glycosylation. It was first identified in podocytes of the renal glomerulus.282 This protein is specifically seen in lymphatic endothelial cells but not in vascular endothelia. In addition, nonendothelial cells in various normal tissues and human neoplasms (seminoma, Kaposi sarcoma, dendritic cell tumors, adrenocortical tumors, adnexal neoplasms of the skin, chondrosarcoma, thymoma, squamous carcinomas, meningioma, solitary fibrous tumor, and others) also express podoplanin.283–287 The principal functions of this protein in normal tissues center on the promotion of lymphatic vasogenesis, podocyte shaping, and platelet aggregation.283

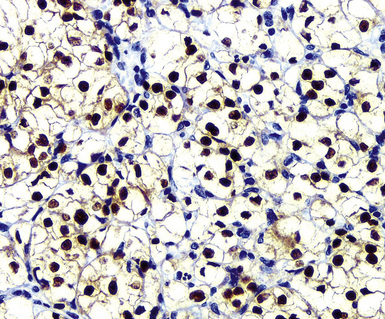

Several studies284,288–292 have shown that podoplanin is a reasonably effective “proactive” marker for mesothelioma (Fig. 20-49). Conversely, it is typically, but not always, absent in carcinomas of the lung and breast.288,292,293 Padgett and coworkers294 reported that podoplanin was a better marker for SMM than calretinin, but 30% of sarcomatoid mesothelial tumors were still podoplanin-negative in that evaluation. We and others290 believe that this analyte is best used in combination with either calretinin or WT1, as a second-tier marker for mesothelioma.

Other Markers

Oncofetal Proteins

The use of antibodies to oncofetal proteins is most commonly undertaken in the study of germ cell tumors. However, their role in the differential diagnosis of mesothelioma has been assessed in a few studies. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, pregnancy-specific glycoprotein, human placental lactogen, and placenta-like alkaline phosphatase have been principally found in adenocarcinomas of various sites.295 However, the sensitivity of these determinants is relatively low, and some examples of human chorionic gonadotropin production by pleural mesotheliomas have indeed been described.296

Blood Group Isoantigens

In addition to Lewis blood group antigens, as typified by BG8 (see previous discussion), some studies have compared the relative reactivities of MM and adenocarcinomas for blood group isoantigens A, B, and H.174,250,297 Their staining patterns generally mirror those of BG8, being restricted to carcinomas, but with lesser sensitivity.

Mesothelin

Mesothelin is a 40-kDa plasmalemmal protein that may function in intercellular adhesion. It is seen in roughly 70% of epithelioid and biphasic MMs, but sarcomatoid mesothelial tumors are negative.298 Controversy has surrounded the differential diagnostic specificity of this marker vis-à-vis mesothelioma, and recent studies have reported mesothelin reactivity in a broad range of carcinomas as well.299

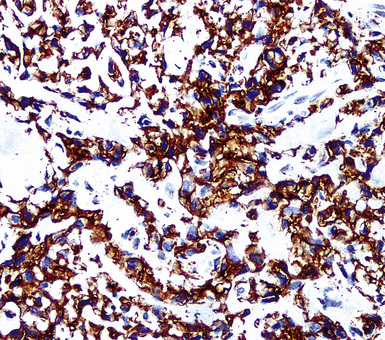

HBME-1 and Cancer Antigen 125

HBME-1 is a monoclonal antibody that was raised against mesothelial cells, and it recognizes a membranous glycoprotein. Although it demonstrates a high degree of sensitivity for MM249,271,279 (Fig. 20-50), several studies over the past decade have shown that it clearly is not a mesothelium-specific reagent. Adenocarcinomas of several sites, including the lung, kidney, thyroid, and female genital tract, are also potentially HBME-1–reactive.244,300–302 Similar comments apply to another mesothelium-related marker, OC125 (recognized by the monoclonal antibody cancer antigen 125 [CA 125])302; in fact, that determinant is widely used to label müllerian carcinomas.303

Neuroendocrine Determinants

Small cell MM may be confused with metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the pleura. With that in mind, it is noteworthy that small cell mesotheliomas commonly manifest immunoreactivity for determinants that are generally regarded as neuroendocrine markers: namely, neuron-specific (gamma-dimer) enolase and CD57.304 However, more specific indicators of a neuroendocrine lineage, such as chromogranin-A, CD56, and synaptophysin, are absent in MMs, and these tumors also lack the paranuclear “dotlike” staining for keratin that is seen in small cell carcinomas.

Additional Hematopoietic Markers

CD15 and CD141 have already been discussed with reference to their relative presence in mesothelial tumors. Other hematopoietic markers of interest in this setting include CD10 (neutral endopeptidase; common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen) and CD138 (syndecan-1). Among epithelial malignancies, CD10 is most commonly used as a potential indicator for RCC and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),305,306 and pleural metastases of these tumors can certainly imitate MM morphologically. Unfortunately, mesotheliomas may also express CD10,307 making it necessary to rely on additional discriminants in this context. On the other hand, CD138 is seen in a variety of carcinomas (e.g., pulmonary, colonic, pancreaticobiliary, hepatocellular, prostatic, renal, transitional cell, mammary, ovarian, endometrial, cutaneous, thyroid, adrenal, and salivary glandular) in differing percentages (Fig. 20-51). MM is consistently CD138-negative.308

Other Supplementary Reagents

Several other antibodies have been applied to the identification of EMMs in the past, and more are likely to appear in the future. For the most part, those that have not been mentioned specifically in this review are not considered to be standard diagnostic markers. However, for purposes of completeness, their relative reactivity patterns in epithelioid mesotheliomas and MACs are provided in Table 20-1 (see also Table 16-1).309–317

Table 20-1 Supplementary Immunohistochemical Reagents Used to Distinguish Epithelioid Mesothelioma from Adenocarcinoma*

| Marker | Mesothelioma† | Adenocarcinomas |

|---|---|---|

| Desmin | ± 37% | — |

| HMFG-2 | ± 15% | ± 75% |

| N-Cadherin | + 73% | ± 30% |

| CD44S | + 73% | ± 48% |

| LN1 | ± 48% | + 86% |

| CD56 | — | ± 16% |

| LN2 | ± 5% | + 91% |

| p21 ras | ± 13% | ± 16% |

| XIAP | ± 80% | ± 50% |

| IMP3 | ± 90% | ± 75% |

| TEN-X | ± 90% | ± 23% |

| PAX2 | ± 4% | ± 65% (Müllerian carcinomas) |

| PAX8 | ± 9% | ± 95% (Müllerian carcinomas) |

| CA 19-9 | ± 20% | ± 70% |

HMFG-2, human milk fat globule protein-2; IMP3, insulin-like growth factor-2 messenger RNA (mRNA)-binding protein-3; PAX, paired box gene; TEN-X, tenascin-X; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein.

* See also text and Table 16-1.

† Percentages are derived from a synthesis of the pertinent literature (also see references 309–317).

Practical Points Regarding the Immunohistochemistry of Mesothelioma

In a critical review of the numerous publications on the immunohistochemistry of MMs, one sees proof of the general tenet that single immunostains cannot be used to establish any given diagnosis with certainty. It is therefore desirable that a panel of reagents be used, including at least two carefully chosen discriminatory antibodies “for” and “against” a diagnosis of mesothelioma.318

Other authors have suggested that the proportion of mesotheliomas that can be recognized confidently increases in direct proportion to the number of antibodies used.253,319 In contrast, Ordoñez244 has recommended that

Using logic regression analysis of 12 markers, Yaziji and colleagues concluded that a 3-marker panel (calretinin, MOC31, and BG8) was diagnostically sufficient and accurate in separating adenocarcinoma from EMM.320 Marchevsky and Wick, Kushitani and associates, and King and coworkers have reached similar conclusions.309,321,322 Thus, we see no practical need to use an exhaustive list of antibody reagents323 in this particular setting.

Cytogenetic and Molecular Features of Pleural Mesothelioma

Cytogenetic studies on human MMs have shown no consistent chromosomal abnormalities.324 Of those that have been reported, several appear to be relatively random events: monosomy 6; assorted trisomies and polysomies; allelic losses of 4p and 4q; deletions of 1p22, 3p, 7q, and 14q; and complete loss of chromosomes 21, 22, and Y.325–331 On the other hand, a relatively consistent deletion of 9p21-22, involving the CDKN2A/INK4A gene, has been seen in up to 60% of cases in some studies.332–335

Mutations in the p53 gene have received substantial attention as possible differential diagnostic tools in mesothelial proliferations.255,258,336–340 However, MM does not inevitably manifest such abnormalities, and they have been reported in 33% to 70% of cases in various series.258,338,340 Point mutations also may occur in the INK4A gene.341

On the other hand, several genes and their protein products may be overexpressed in mesothelioma. They include those coding for platelet-derived growth factors, hepatocyte growth factor, c-met, insulin-like growth factor-1, transforming growth factor-beta, bcl-2, mitogen- activated protein kinase, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase.342–347 HER-2/c-erbB-2, epidermal growth factor receptor, and K-ras genes are not altered in MM.347,348 Interestingly, Ramos-Nino and colleagues have suggested that the activator protein-1 gene complex, encoding transcription factors such as c-fos, Fos-B, Fra-1, Fra-2, c-jun, Jun-B, and Jun-D, is activated in those mesotheliomas that are etiologically related to asbestos.349

Differential Diagnosis of Pleural Mesothelioma: Special Considerations

Differential Diagnosis of Benign versus Malignant Mesothelial Proliferations

Florid Mesothelial Hyperplasia versus Epithelioid Mesothelioma

Mesothelial hyperplasia seen in the context of infectious or inflammatory pleural effusions can be exuberant and moderately atypical cytologically (Fig. 20-52). Especially when the mesothelium becomes entrapped in organizing fibrinous exudates, histologic images in pleural biopsies may engender serious concern over the possibility of EMM.

Differential diagnosis centers on the presence of actual invasion by the proliferation in question, and this can be identified only in an adequate tissue sample. If a deep enough portion of pleura is obtained, one can usually see a zonal phenomenon in mesothelial hyperplasia, wherein the cellularity of the tissue decreases with increasing distance from the pleural surface, and no mesothelial aggregates are visualized in the pleural fibroadipose tissue.156,157 Otherwise, the superficial portions of such specimens may be markedly cellular, even with formation of micropapillary structures that are mantled by atypical mesothelial cells.

As stated above, we are not strong proponents of reliance on immunohistochemical studies in this setting. It has been suggested by others that strong labeling for EMA and p53 protein in the proliferating mesothelium is an indicator of malignancy.215,218,219,257,350 However, we have observed several cases in which both of those markers were unequivocally present in mesothelial proliferations that proved to be benign.

Hopeful assertions also have been made regarding the use of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and the glucose transporter-1 isoform as discriminants of benign and malignant mesothelial proliferations.351,352 Nonetheless, differences of opinion have been advanced regarding the relative merits of these markers.351

Another intriguing recent publication concerns the use of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor-2A (CDKN2A; INK4A; p16) in this setting. That moiety inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase-4 and is encoded by a gene on chromosome 9p21. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization and ThinPrep cytologic preparations of pleural effusion specimens, Illei and associates found that mesotheliomas exhibited homozygous deletion for CDKN2A, whereas reactive benign mesothelium showed retention of at least one copy of the gene.353

Fibrohyaline Pleuritis versus Desmoplastic Mesothelioma

One of the most difficult problems confronting thoracic surgeons and surgical pathologists is the patient who has had a long-standing or recurrent pleural effusion, culminating in a “rind” of organized and densely collagenized tissue that obliterates the pleural space and encompasses the lung. Under these circumstances, the diagnostic alternatives are those of fibrohyaline pleuritis (fibrous pleurisy) and DMM. The distinction between these conditions can be challenging even with a complete pleurectomy specimen in hand, but sufficient sampling is again the key to proper diagnosis. Criteria that are used for recognition of DMM include foci of necrosis, obvious invasion of pleural adipose tissue or subjacent lung, and the presence of obvious focal cellular anaplasia.153,154 p53 immunostaining has again been used by some authors in this context,354 but results of this analysis are similar conceptually to those attending the evaluation of mesothelial hyperplasia, as discussed above.

Differential Diagnosis of Cytologically Malignant Pleural Neoplasms

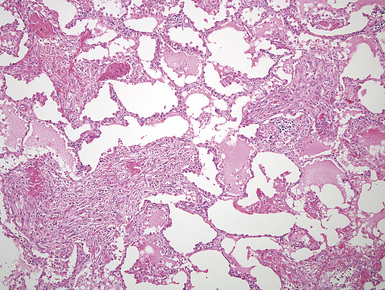

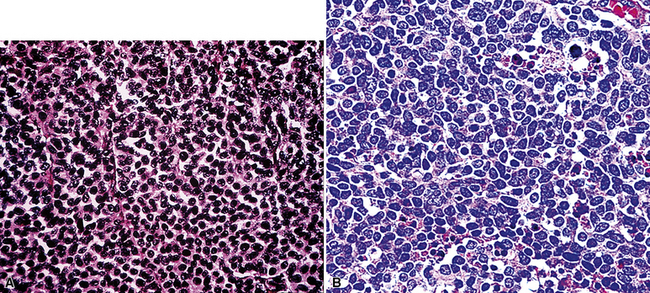

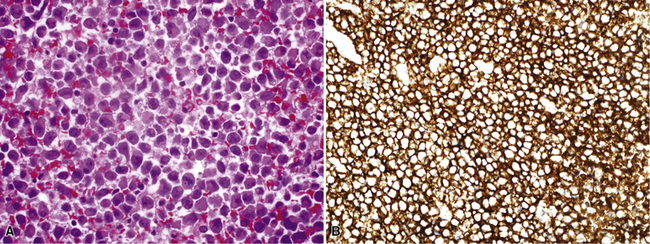

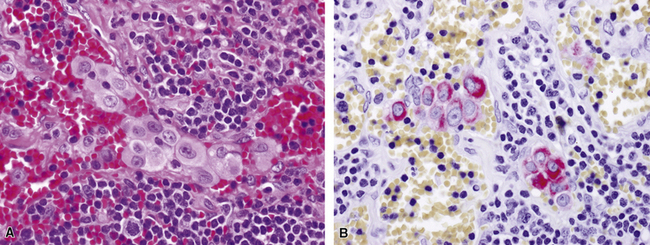

Epithelioid Mesothelioma versus Hematopoietic Malignancies

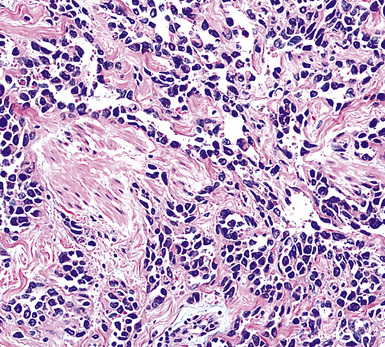

Uncommonly, hematopoietic malignancies such as large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, syncytial or “sarcomatoid” Hodgkin lymphoma, granulocytic sarcoma (tumefactive acute myelogenous leukemia), and plasmacytic myeloma may be primary neoplasms of the pleura and simulate MM, both clinically and morphologically (Fig. 20-53).355–359 These tumors are constituted by large polygonal or round cells, like EMM, and their histologic images are accordingly very similar to that of the solid-anaplastic variety of mesothelioma. Hematopoietic malignancies demonstrate a much more notable degree of apoptosis than that seen in MM, with greater irregularity in the nuclear contours of the tumor cells and more numerous mitoses (Fig. 20-54). Electron microscopic analysis fails to show any intercellular attachment complexes in such lesions, in contrast to their prominence in MMs; similarly, plasmalemmal microvilli are absent in lymphoma and leukemia. Parenthetically, there is a form of large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, known as anemone cell lymphoma, in which numerous cell-surface projections are evident,360 but these structures are not true microvilli.

Immunohistologic studies reveal a lack of keratin and calretinin in hematopoietic tumors, which instead exhibit variable reactivity for CD15, CD20, CD43, CD45, and CD138.359,361 However, CD30 and the WT1 gene product may be reactive in mesothelioma as well as in hematopoietic malignancies.362,363 The latter marker is particularly prevalent in granulocytic sarcoma.

Epithelioid Mesothelioma versus Epithelioid Endothelial Neoplasms

Epithelioid mesothelioma may exhibit cytoplasmic macrovacuolation, a feature also common to epithelioid vascular tumors such as epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) and epithelioid angiosarcoma (EAS), both of which can represent primary pleural neoplasms111,364–368 (Fig. 20-55).

Ultrastructural studies are usually definitive in separating EMM from EHE and EAS. MM shows elaborate microvillous differentiation, complex desmosomes, and cytoplasmic tonofibrils, none of which is apparent in vascular lesions. On the other hand, the cells of EHE and EAS contain variable numbers of Weibel-Palade bodies, which are elongated, tubular, electron-dense cytoplasmic structures with internal striations.369,370

Immunohistologically, epithelioid vascular tumors are unusual mesenchymal neoplasms because they rather commonly exhibit an “aberrant” expression of keratin.371 They are also reactive for CD141281 as are mesothelial proliferations. However, EHE and EAS lack calretinin, WT1 protein, and keratin 5/6, and instead, EHE and EAS are consistently positive for CD31, FLI-1, and CD34372,373 (Fig. 20-56). All of the latter markers are absent in mesotheliomas.

Primary Pleural Myxoid Chondrosarcoma versus Mesothelioma

Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) is a soft tissue tumor that is cytogenetically characterized by two chromosomal translocations, t(9;22)(q22;q11-12) and t(9;17)(q22;q11), which yield the EWS/CHN or RBP56/CHN fusion genes, respectively.374 It has rarely been reported as a primary pleural malignancy,375 and its histologic image may simulate that of epithelioid mesothelioma. However, EMC lacks the microvillous plasmalemmal differentiation of MM on electron microscopy, and instead it shows the presence of cytoplasmic intrareticular microtubules (Fig. 20-57). It is also consistently nonreactive for keratin and calretinin, instead labeling for vimentin and variably for S-100 protein, neuron-specific enolase, and protein gene product 9.5,376,377 none of which is seen in mesotheliomas. On the other hand, stains for podoplanin may be positive in both EMC and MM.378 The characteristic fusion gene proteins of EMC can also be demonstrated rapidly using the polymerase chain reaction,374 and they are consistently lacking in mesothelial tumors.

Synovial Sarcoma versus Mesothelioma

The clinicopathologic characteristics of pleuropulmonary synovial sarcoma have been provided in Chapter 14, including the potential for that tumor to mimic biphasic or sarcomatoid mesotheliomas379 (Fig. 20-58). Specialized pathologic studies are most productive in biphasic tumors, where the microvillous ultrastructural nature of epithelioid cells in MM is not reproduced in synovial sarcoma.380 Additionally, biphasic synovial sarcoma often manifests Ber-Ep4 reactivity, occasionally CD141, and fails to express WT1 in its epithelioid elements.381 Mesotheliomas usually demonstrate the converse of that profile. Diffuse expression of keratins 7 and 19 in mesotheliomas also contrasts with focal labeling for these proteins in synovial sarcoma, whereas keratin 14 may be seen in synovial sarcoma, but not most mesotheliomas. Calretinin and podoplanin are potentially common to both monophasic spindle cell synovial sarcoma and purely sarcomatoid mesothelioma, but WT1 protein is only encountered in MMs. Nuclear immunolabeling for TLE1 is a consistent finding in synovial sarcoma382; to date, there have been no systematic studies addressing the presence or absence of this marker in sarcomatoid mesothelioma.

Ultimately, molecular analysis may be necessary to establish a definitive interpretation in this setting. Virtually all synovial sarcomas show a reproducible t(X;18) chromosomal translocation, which is not seen in MMs. Its presence can be assessed indirectly by using the polymerase chain reaction with primers designed to identify the SYT–SSX1 and SYT–SSX2 fusion proteins that are produced by the translocation in question.383

Pseudomesotheliomatous Sarcomatoid Carcinoma versus Mesothelioma

A related morphologic problem is represented by sarcomatoid carcinomas that extensively involve the pleura and simulate mesothelioma (Fig. 20-59). These lesions may show biphasic or spindle cell/pleomorphic images, and they can originate in the lung, kidney, and breast, as well as at other sites.36 As true in biphasic synovial sarcomas, the ultrastructural and immunophenotypic attributes of epithelioid components in biphasic carcinomas are distinct from those of biphasic MMs.384 Purely nonepithelioid lesions in both categories are more difficult to separate from one another. The presence of immunoreactivity for calretinin and WT1 favors mesothelioma, in our experience, but other authors have come to different conclusions.293

From the perspective of patient management, this diagnostic distinction is not crucial, because pseudomesotheliomatous carcinomas and mesotheliomas generally manifest the same limited response to therapy and a comparably adverse prognosis.34–36 However, medicolegal issues attending the two neoplasms are potentially quite different.

Small Cell Mesothelioma versus Other Small Cell Malignancies

In limited biopsy specimens, small cell mesothelioma may be difficult to distinguish from metastatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNC) involving the pleura385 or from Askin tumor (primary thoracopulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor; PNET). The latter two lesions have been considered in more detail in Chapters 13 and 14. To date, ultrastructural studies on small cell MM have not been performed; hence, it is not known whether it shares the microvillous electron microscopic attributes of conventional epithelioid mesotheliomas, or, alternatively, manifests the formation of blunt neuritic-type cytoplasmic extensions as seen in PNET. Immunohistologically, all three lesions in this differential diagnostic cluster may exhibit reactivity for pankeratin; however, as mentioned earlier, SCNC tends to show distinctive globules of paranuclear keratin reactivity that are not shared by MM or PNET321 (Fig. 20-60). Moreover, keratin 5/6 and calretinin are more often observed in small cell MM than in SCNC,231 and they have not been reported in Askin tumor. Other helpful determinants for the separation of such lesions are hematopoietic in nature. CD99 is unique to PNET in this group, CD56 and CD57 are seen in SCNC and PNET but not small cell MM, and CD141 is seen in mesothelioma but tends to be absent in the other neoplasms.261,386 Metastatic small cell carcinoma of the lung is characteristically positive for the markers MOC-31 and anti–TTF-1,387,388 whereas MM and Askin tumor are negative for these markers.

Primary Pleural Thymomatosis versus Mesothelioma

The capability for thymomas to arise and spread in the pleura, simulating mesothelioma clinicopathologically,389 is discussed in Chapter 19. To reiterate, although both of these tumors share potential immunoreactivity for keratin 5/6, thrombomodulin, and calretinin, only thymomas contain lymphoid cells that express CD1a, terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase, and CD99, and epithelial cells that are labeled for p63 protein.390 Lastly, microvilli are not evident in thymic epithelial neoplasms ultrastructurally.391

Solitary Fibrous Tumor of the Pleura versus Sarcomatoid Mesothelioma

When provided only with small biopsy specimens and given no clinical information, pathologists may conceivably confuse atypical variants of solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura with SMM on morphologic grounds. Nevertheless, the immunophenotypes of these neoplasms are mutually exclusive. Solitary fibrous tumor is reactive for CD34, with or without CD99 and bcl-2 protein, but it lacks keratin. Mesothelioma shows the opposite profile.392 Both lesions may show immunoreactivity for podoplanin.

Clear Cell Mesothelioma versus Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

Clear cell mesotheliomas are rare, but they may be closely simulated by metastases of “conventional” renal cell carcinoma (RCC)393 (Fig. 20-61). The latter of these neoplasms lacks unique and easily detected markers, and, particularly because they also share potential positivity for several proteins with mesothelioma (including keratin, vimentin, CD10, WT1, and thrombomodulin),305,394 a tailored immunohistologic approach to differential diagnosis is necessary in this specific instance. The markers that are most discriminatory between RCC and clear cell MM include keratin 5/6, calretinin, CD15, Ber-Ep4, BG8, and PAX2 (Fig. 20-62). The presence of the first two determinants strongly favors an interpretation of mesothelioma, whereas positivity for any two of the other listed markers is representative of RCC.395,396

Figure 20-62 Nuclear labeling for PAX2 confirms the renal origin of the neoplasm shown in Figure 20-61.

This is a circumstance where electron microscopic study may sometimes be superior in specificity to immunohistochemical analysis. RCCs have poorly formed plasmalemmal microvilli and no cytoplasmic tonofibrils, and, instead, they contain prominent cytoplasmic collections of glycogen, or lipid, or both.397 Clear cell mesothelioma does not share those ultrastructural characteristics, because it is basically a variant of EMM.

Oncocytoid/Deciduoid Mesothelioma versus Other “Pink” Cell Malignancies

Deciduoid/oncocytoid mesothelioma can be simulated by pleural metastases of carcinomas that are constituted by large “pink” cells. These principally include HCC, adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), and RCC.398 Electron microscopy provides valuable information in this particular context, because none of the cited tumors, except for deciduoid MM, contains elongated plasmalemmal microvilli, complex desmosomes, or tonofilaments. Moreover, ACC (and sometimes RCC) may also manifest the presence of tubulovesicular mitochondrial cristae,399 which are absent in mesotheliomas. Immunohistologic separation of such tumors centers on a few key determinants. EMA is consistently present in oncocytoid MM and RCC but is absent in HCC and ACC.400 On the other hand, keratin is paradoxically absent in paraffin sections of ACC, even though it is undeniably epithelial.401 Those two markers are particularly important in regard to the separation of MM and adrenocortical neoplasms, because both of them are commonly positive for calretinin and podoplanin.402 However, ACC also shows reactivity for inhibin (Fig. 20-63) and CD56, both of which are not seen in mesotheliomas.308 The distinction of oncocytoid RCC and MM is basically comparable to that attending their clear cell variants, as discussed previously. Lastly, an antibody known as HepPar1 is contextually selective for HCC and reproducibly allows for a distinction of this tumor from mesotheliomas.306

Rhabdoid Mesothelioma versus Metastases of Extrarenal Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors