Chapter 16 Pulmonary Stenosis with Interatrial Communication

In 1769, Giovanni Battista Morgagni1 described pulmonary stenosis with a patent foramen ovale, and in 1848, Thomas Peacock2 published “Contraction of the Orifice of the Pulmonary Artery and Communication Between the Cavities of the Auricles by a Foramen Ovale.”

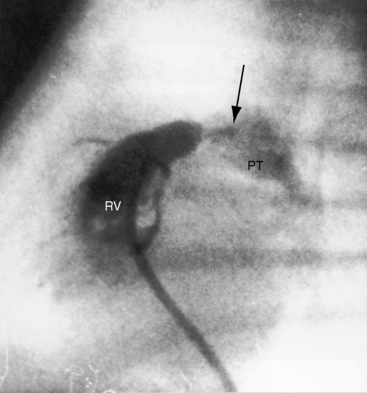

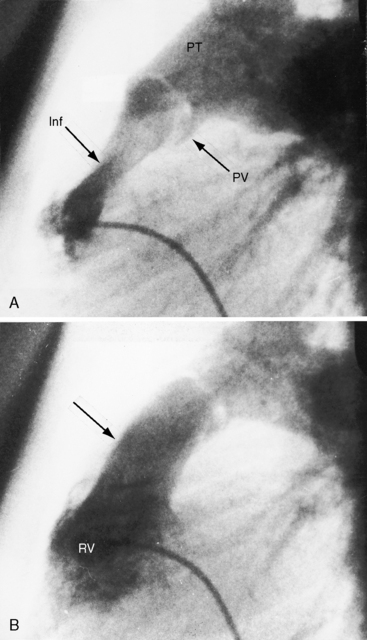

Pulmonary stenosis with reversed interatrial shunt has been called the triologie de Fallot.3 Right ventricular outflow obstruction resides in a stenotic mobile dome-shaped pulmonary valve (Figure 16-1) and is occasionally represented by stenosis of the pulmonary artery and its branches (Figure 16-2).4–7 Infundibular obstruction takes the form of secondary hypertrophic subpulmonary stenosis (Figure 16-3).8–11 The interatrial communication is by a patent foramen ovale or an ostium secundum atrial septal defect,4,6,8,12–15 less commonly by an ostium primum16 or sinus venosus atrial defect,14 or much less commonly by anomalous pulmonary venous connection.17 This chapter deals with pulmonary valve stenosis and a patent foramen ovale or a nonrestrictive ostium secundum atrial septal defect.4

Severe pulmonary valve stenosis with a right-to-left shunt through a patent foramen ovale is more common than pulmonary valve stenosis with a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect, irrespective of the direction of the shunt.4 A restrictive interatrial communication is almost always a patent foramen ovale, the shunt is right-to-left, and pulmonary stenosis is necessarily severe.4,18 A nonrestrictive interatrial communication is almost always an ostium secundum atrial septal defect, the shunt is left-to-right, and pulmonary stenosis is necessarily mild to moderate.4–6,8,12

The physiologic consequences of pulmonary stenosis with an interatrial communication depend on the degree of obstruction to right ventricular outflow and the size of the interatrial communication.4,18 Patients with pulmonary stenosis and a right-to-left interatrial shunt (Figure 16-4) almost always have a severely stenotic pulmonary valve and a patent foramen ovale (see previous).4 Patients with pulmonary stenosis and a left-to-right interatrial shunt almost always have a mild to moderate pulmonary valve stenosis and a nonrestrictive ostium secundum atrial septal defect (see previous).4

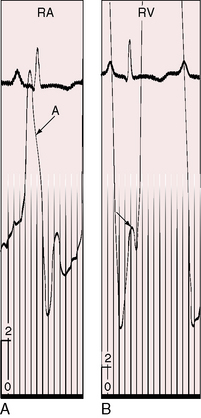

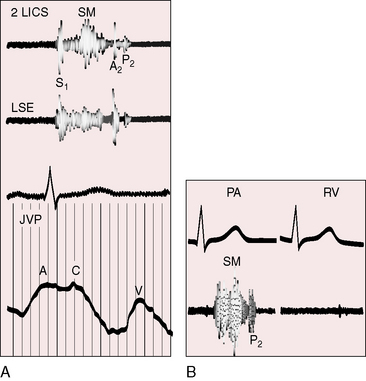

Severe pulmonary stenosis with right ventricular hypertrophy results in an increase in force of right atrial contraction (Figures 16-5 and 16-6) that generates a presystolic right-to-left interatrial shunt. High right atrial pressure stretches the margins of the foramen ovale and increases its patency. When right atrial blood escapes through the interatrial communication, pulmonary flow tends to fall reciprocally.

A nonrestrictive atrial septal defect with a large left-to-right shunt and mild to moderate pulmonary valve stenosis clinically resembles an isolated atrial septal defect (see Chapter 15). The small gradients generated by hyperkinetic right ventricular ejection across a normal pulmonary valve can generate a small gradient that should not be mistaken for mild pulmonary stenosis.

history

Familial pulmonary valve stenosis with atrial septal defect has been reported in a mother and her two children.19 Severe pulmonary stenosis with a right-to-left shunt across a patent foramen ovale is clinically analogous to isolated severe pulmonary valve stenosis, except for cyanosis that can be present at birth13,18 or can develop in childhood, puberty, or young adulthood.6,8,13,20 Infants usually come to attention because of a murmur; although in neonates with pinpoint pulmonary valve stenosis (see Figure 16-1), the murmur is disarmingly soft. Symptoms can be appreciable even when cyanosis is mild13,21 because right ventricular pressure can exceed systemic before the right-to-left interatrial shunt is established. However, among the author’s patients are a teenager who became cyanotic only when he engaged in sports,8 a woman with severe pulmonary stenosis and reversed interatrial shunt who was in good health until age 40 years,14 and a woman with a gradient of 120 mm Hg who underwent surgical repair at age 58 years (see Figure 16-5).

Giddiness, light-headedness, and syncope are provoked by exertion. Large jugular venous A waves (see Figure 16-5) are sometimes subjectively sensed, especially after effort or excitement. Chest pain that resembles angina pectoris is attributed to ischemia in the high-pressure hypertrophied right ventricle. Death is usually from right ventricular failure and less commonly from hypoxia, cerebral abscess, or infective endocarditis.5,6

Mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis with a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect clinically resembles an isolated nonrestrictive ostium secundum atrial septal defect (see Chapter 15), except for the conspicuous murmur of pulmonary stenosis.18 Relatively asymptomatic survival into the sixth and seventh decades is not uncommon. A 59-year-old man had a nonrestrictive sinus venous defect and calcific pulmonary stenosis.14

Physical appearance

Retarded growth and development are consequences of right ventricular failure that begins in infancy or early childhood. Cyanosis associated with pulmonary stenosis and a patent foramen ovale can be obvious or evident only during exercise.8,22,23 Mild or intermittent right-to-left shunts are sometimes manifested by highly colored cheeks or by distinctive erythema of the fingertips and toes (see Figure 16-4).8,20,21 The central cyanosis of a right-to-left shunt must be distinguished from the peripheral cyanosis of diminished skin blood flow caused by the low cardiac output of severe pulmonary stenosis. Peripheral cyanosis is accompanied by cold hands and feet and tends to be more pronounced in the lower extremities. When skin blood flow is improved by warmth, peripheral cyanosis diminishes or may vanish, and central cyanosis becomes more evident.

Children with a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect and mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis may have a delicate gracile body habitus, with weight more affected than height (see Figure 15-14). Noonan’s syndrome (see Figure 11-8C) is a distinctive appearance associated with dysplastic pulmonary valve stenosis that may coexist with an atrial septal defect.

jugular venous pulse

When pulmonary stenosis coexists with a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect, the hypertrophied right ventricle is less distensible, the right atrium contracts with greater force, and the A wave is prominent. The contour and height of the jugular pulse are determined by the presence and degree of pulmonary stenosis, not by the atrial defect. When pulmonary stenosis is severe enough to reverse the shunt, the jugular venous A wave is large, even giant (see Figures 16-5 and 16-6A). With the advent of right ventricular failure, the mean jugular venous pressure rises, and with it the V wave, especially if tricuspid regurgitation coexists.

Precordial movement and palpation

Pulmonary stenosis with a right-to-left interatrial shunt is associated with precordial palpation similar to severe isolated pulmonary valve stenosis (see Chapter 11). A nonrestrictive atrial septal defect with mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis is associated with precordial signs similar to an isolated atrial septal defect of equivalent size, except for a systolic thrill of coexisting pulmonary valve stenosis.23

Auscultation

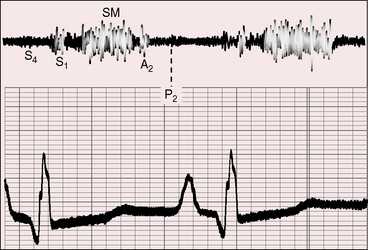

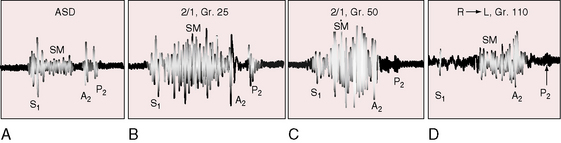

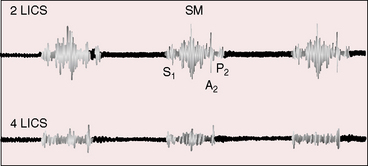

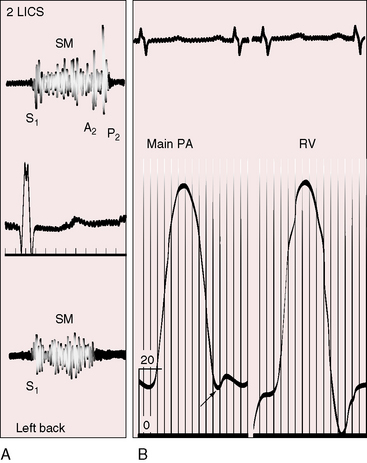

Severe pulmonary valve stenosis with a right-to-left interatrial shunt is accompanied by auscultatory signs analogous to isolated severe pulmonary stenosis (see Chapter 11). The systolic murmur is maximal in the second left intercostal space (Figure 16-7); radiates upward and to the left; extends up to or beyond the aortic component of the second heart sound, which it obscures (Figures 16-7 and 16-8A and D);24 and has a late systolic peak with a kite-shaped configuration.24,25 In neonates with critical pulmonary valve stenosis and right ventricular failure, the murmur is short and soft (see previous), and the pulmonary component of the second heart sound is delayed, soft, or absent (see Figures 16-7 and 16-8D). The most prominent auscultatory sign is then a holosystolic murmur of tricuspid regurgitation (see Figure 16-5).

Presystolic distention of the right ventricle (see Figure 16-6B) is accompanied by a fourth heart sound that is occasionally long enough to qualify as a murmur (see Figures 16-5 and 16-7). A short presystolic murmur is also generated when powerful right atrial contraction forces blood across a restrictive patent foramen ovale. A large right atrial A wave that is transmitted into the right ventricle (see Figure 16-6) can exceed the diastolic pressure in the main pulmonary artery, open the pulmonary valve, and generate presystolic flow and a presystolic murmur.

When a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect is associated with mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis, the auscultatory signs resemble an isolated nonrestrictive ostium secundum atrial septal defect with three exceptions: 1, an ejection sound is generated by the mobile stenotic pulmonary valve; 2, the pulmonary systolic murmur is loud and long (Figures 16-9 and 16-10); and 3, the second heart sound is more widely split because of a greater delay in the pulmonary component (see Figures 16-8B and C, 16-9, and 16-10). The more severe the pulmonary stenosis, the later and softer the pulmonary component of the second heart sound (see Figures 16-7 and 16-8).

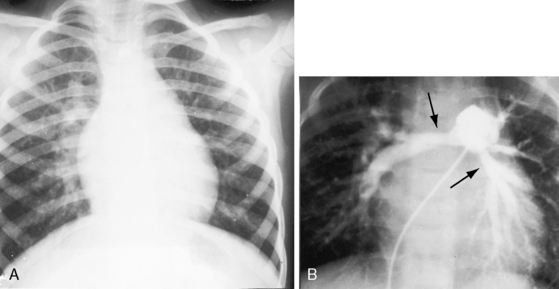

Stenosis of the pulmonary artery and its branches with an ostium secundum atrial septal defect (Figure 16-11) is accompanied by conspicuously wide thoracic distribution of systolic murmurs because the murmurs of pulmonary artery stenosis are reinforced by hyperkinetic pulmonary blood flow of the atrial septal defect. Persistent splitting of the second heart sound is the result of the atrial septal defect (see Figure 16-11).

electrocardiogram

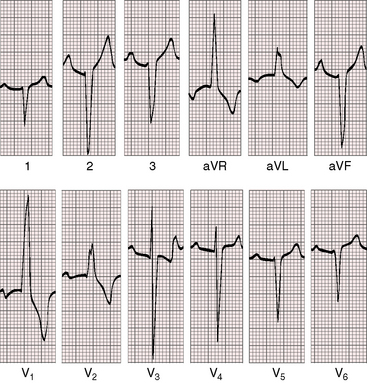

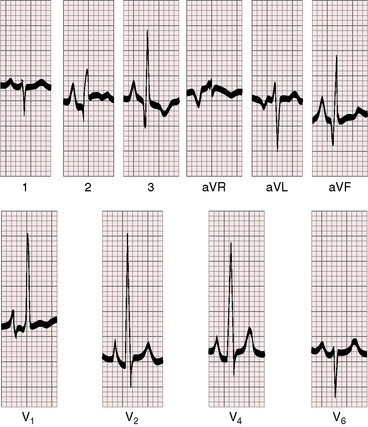

In pulmonary valve stenosis with a right-to-left interatrial shunt, the electrocardiogram is similar to that of severe isolated pulmonary stenosis (Figures 16-12 and 16-13; see Chapter 11).26 Peaked right atrial P waves appear in lead 2 and in right precordial leads (see Figures 16-7, 16-12, and 16-13) and occasionally are exceptionally tall (see Figures 16-7 and 16-12).8,22 P wave duration in lead 2 is prolonged when a large right atrium writes the terminal inscription of the P wave.27 Right axis deviation (see Figure 16-12) can be extreme (see Figure 16-13). The terminal force of the QRS can be prolonged and slurred (see Figure 16-13). Right ventricular hypertrophy caused by suprasystemic right ventricular systolic pressure is manifested by R waves of great amplitude in right and mid precordial leads with upward convexity of ST segments and deeply inverted T waves, together with deep left precordial S waves (see Figures 16-12 and 16-13).26 The striking ST segment and T wave patterns sometimes extend to lead V4. Small q waves appear in lead V1 (see Figure 16-13) when the precordial electrode topographically overlies a large right atrium (see Chapter 13).

Figure 16-12 Electrocardiogram from the 5-month-old cyanotic female referred to in Figure 16-7 with severe pulmonary valve stenosis and a right-to-left shunt across a patent foramen ovale. Tall peaked right atrial P waves appropriate for the 20–mm Hg A wave in the right atrium appear in leads 2, 3, aVF, and V1-4. Right axis deviation and right ventricular hypertrophy are manifested by tall monophasic R waves in leads V1-4 and a deep S wave in lead V6, findings appropriate for suprasystemic right ventricular systolic pressure.

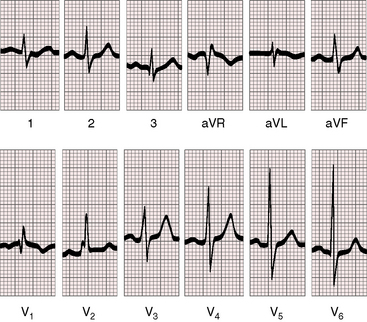

In a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect with a left-to-right shunt and mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis, the electrocardiogram is a combination of isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect (see Chapter 15) and the right ventricular hypertrophy of pulmonary stenosis (Figures 16-14 and 16-15). P waves can be peaked and moderately tall (see Figure 16-14). The QRS axis is vertical or rightward (see Figures 16-14 and 16-15). Terminal force prolongation widens the R wave in lead aVR and widens the S waves in leads 1, aVL, and V6 (see Figures 16-14 and 16-15). The rsR prime in lead V1 is characterized by a relatively small s wave and a relatively tall R prime compared with an atrial septal defect without pulmonary stenosis (see Figures 16-14 and 16-15).

Figure 16-15 Electrocardiogram from the 23-year-old man referred to in Figure 16-9 with a 2.4 to 1 left-to-right shunt through an ostium secundum atrial septal defect and a 45–mm Hg gradient across a mobile stenotic pulmonary valve. The normal P waves, the vertical QRS axis, the rsR prime in lead V1, and the slight prolongation of the terminal force in leads V1 and aVR are appropriate for the atrial septal defect.

x-ray

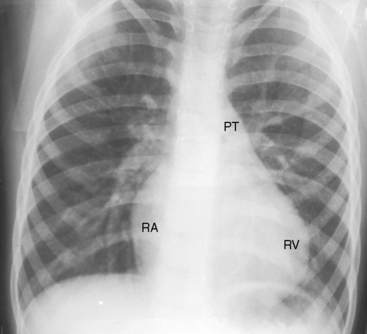

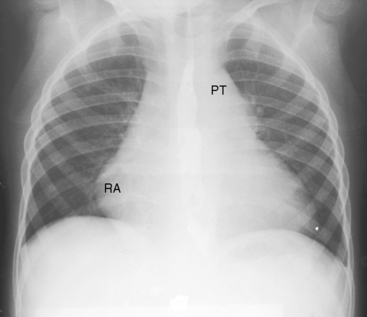

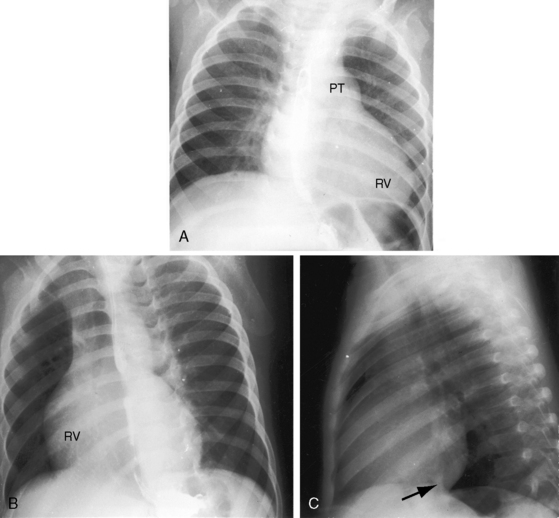

Nonrestrictive atrial septal defects with mild to moderate pulmonary stenosis have x-rays indistinguishable from isolated ostium secundum defects (Figure 16-16).28 Severe pulmonary stenosis with a right-to-left interatrial shunt through a patent foramen ovale is associated with an x-ray that resembles that of isolated severe pulmonary valve stenosis (Figure 16-17; see Chapter 11). Lung fields are oligemic because right atrial blood is shunted away from the lungs across the atrial septum. The reduced right ventricular output and pulmonary blood flow become even more apparent with the advent of right ventricular failure. The pulmonary trunk is dilated (Figures 16-1, 16-3, 16-17, and 16-18) for reasons analogous to dilation in isolated mobile pulmonary valve stenosis (see Chapter 11).5,8 Heart size is increased because of enlargement of the right atrium and right ventricle (see Figures 16-17 and 16-18).8,13 The right ventricular apex is not boot-shaped as in Fallot’s tetralogy because the size of the left ventricle is not reduced (see Figure 16-17; see Chapter 18).

Figure 16-17 X-rays from the 15-month-old cyanotic male referred to in Figure 16-6 with severe mobile pulmonary valve stenosis, suprasystemic right ventricular systolic pressure, and a right-to left shunt through a patent foramen ovale. A, The pulmonary trunk (PT) is dilated. An enlarged right ventricle (RV) occupies the apex. B, The left anterior oblique shows a dilated right ventricle (RV) displacing the left ventricle posteriorly. C, In this lateral projection, the normal location of the inferior vena cava (arrow) at the junction of the left ventricle and diaphragm indicates that the left ventricle in not enlarged.

echocardiogram

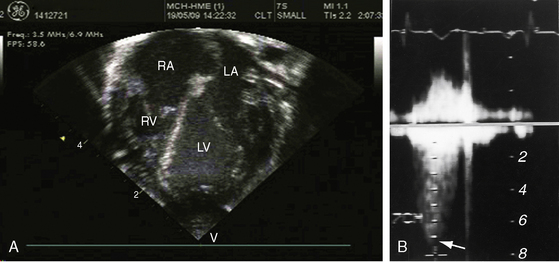

Mobile pulmonary valve stenosis with a right-to-left shunt through a patent foramen ovale is associated with an echocardiogram similar to isolated severe pulmonary valve stenosis (see Chapter 11). Color flow imaging records a high-velocity jet directed toward the left pulmonary artery (Figure 16-19A and Videos 16-1A through 16-1C), and continuous-wave Doppler scan establishes the peak velocity and the gradient (Figure 16-19B). Two-dimensional imaging identifies the patent foramen ovale with its valve (see Chapter 15), and color flow imaging confirms the right-to-left shunt.

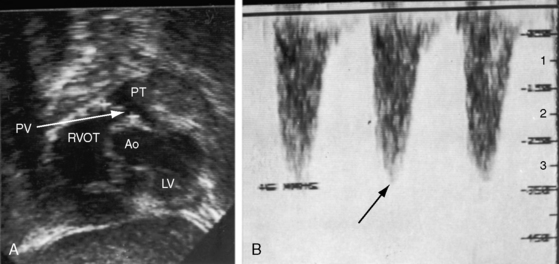

A nonrestrictive ostium secundum atrial septal defect with mild to moderate pulmonary valve stenosis is associated with an echocardiogram similar to that of an isolated atrial septal defect of the same location and size (see Chapter 15), except for coexisting pulmonary stenosis. Real-time imaging identifies the mobile stenotic pulmonary valve, and Doppler interrogation establishes the gradient (Figure 16-20).

1 Morgagni J. Seats and causes of diseases. London: Millar & Cadell in the Strand and Johnson & Payne in Pater-Noster Row; 1769.

2 Peacock T. Contraction of the orifice of the pulmonary artery and communication between the cavities of the auricles by the foramen ovale. Transactions of the Pathological Society of London. 1848;1:200.

3 Joly F., Carlotti J., Sicot J.R., Piton A. Congenital heart disease. II. Fallot’s trilogies. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1950;43:687-704.

4 Roberts W.C., Shemin R.J., Kent K.M. Frequency and direction of interatrial shunting in valvular pulmonic stenosis with intact ventricular septum and without left ventricular inflow or outflow obstruction. An analysis of 127 patients treated by valvulotomy. Am Heart J. 1980;99:142-148.

5 Selzer A., Carnes W.H. The types of pulmonary stenosis and their clinical recognition. Mod Concepts Cardiovasc Dis. 1949;18:45.

6 Selzer A., Carnes W.H., et al. The syndrome of pulmonary stenosis with patent foramen ovale. Am J Med. 1949;6:3-23.

7 Shafter H.A., Bliss H.A. Pulmonary artery stenosis. Am J Med. 1959;26:517-526.

8 Campbell M. Simple pulmonary stenosis; pulmonary valvular stenosis with a closed ventricular septum. Br Heart J. 1954;16:273-300.

9 Johnson A.M. Hypertrophic infundibular stenosis complicating simple pulmonary valve stenosis. Br Heart J. 1959;21:429-439.

10 Little J.B., Lavender J.P., Desanctis R.W. The narrow infundibulum in pulmonary valvular stenosis: its preoperative diagnosis by angiocardiography. Circulation. 1963;28:182-189.

11 White P.D., Hurst J.W., Fennell R.H. Survival to the age of seventy-five years with congenital pulmonary stenosis and patent foramen ovale. Circulation. 1950;2:558-564.

12 Arnett E.N., Aisner S.C., Lewis K.B., Tecklenberg P., Brawley R.K., Roberts W.C. Pulmonic valve stenosis, atrial septal defect and left-to-right interatrial shunting with intact ventricular septum. A distinct hemodynamic-morphologic syndrome. Chest. 1980;78:759-762.

13 Engle M.A., Taussig H.B. Valvular pulmonic stenosis with intact ventricular septum and patent foramen ovale; report of illustrative cases and analysis of clinical syndrome. Circulation. 1950;2:481-493.

14 Hardy W.E., Gnoj J., Ayres S.M., Giannelli S.Jr, Christianson L.C. Pulmonic stenosis and associated atrial septal defects in older patients. Report of three cases, including one with calcific pulmonic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1969;24:130-134.

15 Ordway N.K., Levy L.2nd, Hyman A.L., Bagnetto R.L. Pulmonary stenosis with patent foramen ovale. Am Heart J. 1950;40:271-284.

16 Rudolph A.M., Nadas A.S., Goodale W.T. Intracardiac left-to-right shunt with pulmonic stenosis. Am Heart J. 1954;48:808-816.

17 Neptune W.B., Bailey C.P., Goldberg H. The surgical correction of atrial septal defects associated with transposition of the pulmonary veins. J Thorac Surg. 1953;25:623-634.

18 De Castro C.M., Nelson W.P., Jones R.C., Hall R.J., Hopeman A.R., Jahnke E.J. Pulmonary stenosis: cyanosis, interatrial communication and inadequate right ventricular distensibility following pulmonary valvotomy. Am J Cardiol. 1970;26:540-543.

19 Ciuffo A.A., Cunningham E., Traill T.A. Familial pulmonary valve stenosis, atrial septal defect, and unique electrocardiogram abnormalities. J Med Genet. 1985;22:311-313.

20 Abrahams D.G., Wood P. Pulmonary stenosis with normal aortic root. Br Heart J. 1951;13:519-548.

21 Silverman B.K., Nadas A.S., Wittenborg M.H., Goodale W.T., Gross R.E. Pulmonary stenosis with intact ventricular septum; correlation of clinical and physiologic data, with review of operative results. Am J Med. 1956;20:53-64.

22 Allanby K., Campbell M. Congenital pulmonary stenosis with closed ventricular septum. Guys Hosp Rep. 1949;98:18.

23 Evans J.R., Rowe R.D., Keith J.D. The clinical diagnosis of atrial septal defect in children. Am J Med. 1961;30:345-356.

24 Vogelpoel L., Schrire V. Auscultatory and phonocardiographic assessment of pulmonary stenosis with intact ventricular septum. Circulation. 1960;22:55.

25 Gamboa R., Hugenholtz P.G., Nadas A.S. Accuracy of the phonocardiogram in assessing severity of aortic and pulmonic stenosis. Circulation. 1964;30:35-46.

26 Burch G.E., Depasquale N.P. The electrocardiogram, vectorcardiogram and ventricular gradient in combined pulmonary stenosis and interatrial communication. Am J Cardiol. 1961;7:646-656.

27 Macruz R., Perloff J.K., Case R.B. A method for the electrocardiographic recognition of atrial enlargement. Circulation. 1958;17:882-889.

28 Magidson O., Cosby R.S., Dimitroff S.P., Levinso D.C., Griffith G.C. Pulmonary stenosis with left to right shunt. Am J Med. 1954;17:311-321.