Pulmonary Nodule (Case 11)

Smitha Gopinath Nair DO and Jennifer LaRosa MD

Case: The patient is a 68-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus who recently moved to New York from Ohio and presents for her annual physical examination. She is noted to have a 35 pack-year history of cigarette smoking and briefly worked with her husband installing home insulation. She complains of productive cough upon awakening every morning and dyspnea with moderate activity. On physical examination she is noted to be well dressed and overweight. Her lung exam reveals mild wheezing, and she has some clubbing of her fingers. A routine chest radiograph reveals a 1-cm nodule in the right mid-lung field.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Primary lung cancer |

Coccidioidal pulmonary nodule |

|

|

Dirofilariasis |

Hamartoma |

Histoplasma pulmonary nodule |

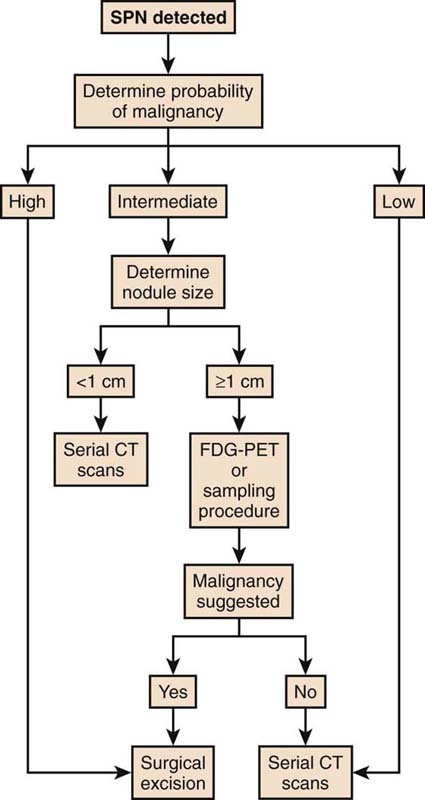

A solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) is a common clinical problem. It is typically an incidental finding on chest roentgenogram or CT scan of the chest, and in one study was seen in 25% of healthy, asymptomatic individuals. The majority of nodules will have a benign etiology. However, since lung cancer is both asymptomatic and curable in its early stages, it is imperative that all nodules be considered malignant until proven otherwise. The recommendations for further testing to evaluate the pulmonary nodule vary according to the pretest probability. If the pretest probability is less than 5%, the nodule should be followed with serial CT scans at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. If it is between 5% and 60%, options include CT scan, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, biopsy, or resection. A pulmonologist may be consulted for guidance. If the pretest probability is greater than 60%, biopsy and resection should be strongly considered. See Figure 17-1.

Figure 17-1 Algorithm for solitary pulmonary nodule. (Reproduced with permission from Weinberger SE. Diagnostic evaluation and initial management of the solitary pulmonary nodule. In: UptoDate, Basow, DS (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2011. Copyright © 2011 UptoDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.)

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• There are patient characteristics that can suggest one etiology as being more likely than another.

History

• The presence of occupational and environmental risk factors, especially cigarette smoking, should be diligently sought. Tobacco smoking increases a patient’s relative risk of lung cancer 10- to 30-fold over that of nonsmokers; this risk decreases after 5 years of smoking cessation but never falls to the level of a patient with no smoking history.

• A past medical history of malignancy raises the suspicion of metastatic lung disease. Extrapulmonary malignancies that are most likely to lead to pulmonary metastases include sarcoma, malignant melanoma, and carcinomas of breast, colon, kidney, and testicle.

• Cough is a nonspecific symptom and may accompany any potential cause of SPN.

Physical Examination

As stated earlier, an SPN is defined by its size (<3 cm) and the fact that it does not distort or affect surrounding tissues. Therefore, the SPN rarely, if ever, causes abnormal findings on physical exam.

Tests for Consideration

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Primary Lung Cancer |

|

|

Pφ |

The pathophysiology of lung cancer is intricate and not completely understood. What is thought to influence pathogenesis are genes that produce proteins involved in cell growth and differentiation, cell cycle processes, apoptosis, angiogenesis, tumor progression, and immune regulation. When there is dysregulation between cell growth and apoptosis, this leads to malignancy. The identification of the mechanism that produces this asynchrony may lead to the development of better risk stratification, prevention, and therapy. |

|

TP |

Lung cancers that present as an SPN are typically incidental findings and have a better prognosis. Lung cancers that are found secondary to symptoms are more advanced and have a worse prognosis. Common symptoms include cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and weight loss. The most common cell type is adenocarcinoma, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and the less common small cell carcinoma typically originate as a peripheral lesion, whereas squamous cell carcinoma is typically discovered as a central lesion. |

|

CT scan of the chest and PFTs are essential for all patients with a lesion potentially consistent with lung cancer. CT scan will reveal characteristics of the lesion that make it more or less likely to be malignant. Abnormal PFTs demonstrating a pattern consistent with emphysema make lung cancer a more likely diagnosis in a newly discovered SPN. All lesions with a possibility of lung cancer must be considered for biopsy or resection. |

|

|

Tx |

Stage I lung cancer can be cured by resection. This reason alone makes appropriate workup of an SPN essential. More advanced stages of lung cancer can be treated with a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Despite these treatment options, prognosis for advanced lung cancer remains poor. |

|

Dirofilariasis |

|

|

Pφ |

Pulmonary dirofilariasis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis, a zoonotic filarial nematode commonly carried in the gastrointestinal tracts of dogs, coyotes, wolves, and cats. Humans may become infected via the fecal-oral route through contact with these animals. The human represents a dead-end host where the filariae travel to the lungs and are consumed by the granulomatous process. |

|

TP |

Human infections are usually asymptomatic. Rarely, individuals may have self-limited infection with chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, fever, and malaise. |

|

Dx |

Definitive diagnosis is made only if the patient undergoes a biopsy. A peripheral eosinophilia of about 10% may also be present, but this finding is nonspecific for dirofilariasis. Serology using indirect hemagglutination or ELISA is available but not widely employed. |

|

Tx |

No therapy is generally required. In rare cases, ivermectin followed by diethylcarbamazine may be necessary. |

|

Hamartoma |

|

|

Pφ |

Hamartomas result from an abnormal formation of normal tissue. They grow along with, and at the same rate as, the organ from whose tissue they are made. They rarely invade or compress surrounding structures. They are benign lesions usually arising from connective tissue and are generally formed of fat, cartilage, and connective tissue cells. Lung hamartomas are more common in men than in women. |

|

Hamartomas are generally asymptomatic. Some lung hamartomas can compress surrounding lung tissue, but this is generally not debilitative or even noticed by the patient, especially for the more common peripheral lesions. The great majority of them form in the connective tissue on the surface of the lungs, although about 10% form deep in the linings of the bronchi. |

|

|

Dx |

CT scan may show characteristic cartilage and fat cells. When it does not, it may be confused with a malignancy, and biopsy may become necessary. |

|

Tx |

They are treated, if at all, by surgical resection. The prognosis is excellent. |

|

Coccidioidal Pulmonary Nodule |

|

|

Pφ |

Coccidioidomycosis is an infection caused by a dimorphic fungus, most commonly Coccidioides immitis. The majority of cases in the United States occur in the San Joaquin River Valley and Saguaro Desert. Infection may be acquired by inhalation of a single arthroconidium. Within the lung, the arthroconidium becomes spherical and enlarges. In several days the mature spherules rupture, releasing endospores into the infected tissue. Each endospore is capable of producing more spherules and further disseminating the disease. In most cases, however, the spherules are consumed and contained by granulomatous inflammation. |

|

TP |

The majority of patients will be asymptomatic or have a self-limited illness with cough and fever. |

|

Dx |

Isolation of the organism in culture establishes the diagnosis. Other options include serologic tests for antibodies and nucleic acid amplification tests such as PCR. PCR testing is 100% sensitive and 98% specific. Biopsy is an alternate way to make the diagnosis. Staining with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, or Grocott–methenamine silver stain will demonstrate the organism. |

|

Tx |

Treatment is rarely necessary, as the disease is usually self-limited. However, immunocompromised hosts, such as those with malignancy or HIV infection, will need to receive antifungal therapy in the form of fluconazole or itraconazole. An amphotericin B preparation should be considered only in severe or widely disseminated cases. |

|

Pφ |

Lungs are the port of entry for Histoplasma capsulatum. Within the United States it is most common in the midwestern states. Macrophages initially ingest but cannot kill the fungus. Cellular immunity develops in 10–14 days after exposure in immunocompetent hosts. Sensitized T lymphocytes, tumor necrosis factor, and interferon-α are important mediators in the host defense against Histoplasma infection. |

|

TP |

Less than 5% of patients develop symptoms. For those who do, symptoms are nonspecific and may include fever, chills, headache, myalgias, anorexia, cough, and chest pain. |

|

Dx |

Serologic tests for Histoplasma-specific antibodies reveal the diagnosis. Histopathology using stains for fungi, culture, and antigen detection in the urine, blood, or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid may also be employed. |

|

Tx |

Most infections by Histoplasma are self-limited, and no therapy is required. However, immunocompromised patients or those exposed to a large inoculum may require antifungal therapy. Itraconazole is used in mild to moderate histoplasmosis, and an amphotericin B preparation is used for severe infections. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Early Lung Cancer Action Project (ELCAP)

Authors

Henschke C, McCauley D, Yahnkelevitz D, et al.

Institution

Cornell, Columbia, New York University medical centers, New York, NY, USA; McGill University, Montreal, PQ, Canada

Reference

Lancet 1999;354:99–105

Problem

Overall 5-year survival of lung cancer is about 12%. Five-year survival for stage I cancer is 70%. This implies that lung cancer screening would improve survival.

Intervention

A total of 1000 asymptomatic patients who had smoked the equivalent of at least 10 pack-years underwent lung cancer screening with low-dose spiral CT and chest radiograph.

Outcome/effect

CT scans detected more benign and malignant nodules compared to chest radiographs (benign, 20.6% vs. 6.1%; malignant, 2.7% vs. 0.7%). Over 95% of the nodules were benign based on radiographic stability or tissue biopsy. Of the 27 malignancies identified, 23 of them were stage I disease. This study brings two major points to light: (1) CT scan identified three to four times as many SPNs as chest radiographs, and (2) the majority of identified malignancies were stage I and curable with resection.

Historical significance/comments

This was the first screening and follow-up study that employed CT scanning for detecting lung nodules in the hopes of detecting lung cancer at an earlier stage than chest radiography.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Develop a Sensitive Style to Deliver Unexpected News

A solitary nodule is found incidentally on approximately 0.20% of chest radiographs and even more frequently on CT scans of the thorax. As a physician, you will frequently be called upon to deliver news of an unexpected finding. Though the initial conversation about such a finding may be one of many such conversations during the course of your career, hearing such news for the first time creates a memory for your patient that may be “replayed” frequently. It is important that your initial contact about an unexpected finding be informative, honest, straightforward, and sensitive. If you can honestly be reassuring, let the patient know that the finding “may not be important or significant, though it may require further workup.” If you believe this is a finding of great concern, you should articulate your concerns but with terms that are as hopeful as possible, such as “We’ll define this and determine what the very best treatment should be.”

Professionalism

Recognize Personal Boundaries When Caring for Family Members

If one of your close relatives is found to have a solitary pulmonary nodule on routine chest radiograph, how would you interact with her or his doctor? Would you insist she or he be seen immediately by a specialist at a high-volume center? Would your relative expect you to set up immediate follow-up? As a basic principle, it is important to respect the boundary between family and professional practice. Honor the relationship that relatives may have with their physician, and offer your opinion only when asked. If you have serious concerns about the management, it is appropriate to ask your relative if he or she would like you to discuss the issues with his or her physician. Alternatively, sometimes physicians do not make necessary calls to a relative’s doctor because they think it may be easier to address the problem on their own, or they don’t want to “bother” a colleague with more phone calls to return. It’s important to recognize that objectivity doesn’t always exist when a patient is a close relative or friend. It can be difficult to relinquish the role of physician in the family environment, but, in general, being the family member is the best role to take; let your relative’s physician be the doctor.

Systems-Based Practice

Standardizing Follow-up for Incidentally Detected Lung Nodules

Optimizing successful outcomes for patients with pulmonary nodules should be based on a standardized and thorough approach to each patient. The Fleischner Society has provided recommendations for follow-up for patients with incidental pulmonary nodules (Table 17-1). These recommendations are based on nodules smaller than 8 mm detected incidentally on nonscreening CT scans with varying recommendations based on whether the patient is at low risk (minimal or absent history of smoking and of other known risk factors for cancer) or high risk (history of smoking and of other known risk factors for cancer). These recommendations are useful in providing guidance for management of the patient with a pulmonary nodule.

|

Nodule Size (mm)* |

Low-Risk Patient† |

High-Risk Patient‡ |

|

≤4 |

No follow-up needed§ |

Follow-up CT at 12 months; if unchanged, no further follow-up |

|

>4–6 |

Follow-up CT at 12 months; if unchanged, no further follow-up |

Initial follow-up CT at 6–12 months, then at 18–24 months if no change |

|

>6–8 |

Initial follow-up CT at 6–12 months, then at 18–24 months if no change |

Initial follow-up CT at 3–6 months, then at 9–12 and 24 months if no change |

|

>8 |

Follow-up CT at around 3, 9, and 24 months, dynamic contrast-enhanced CT, PET, and/or biopsy |

Same as for low-risk patient |

|

Note: Newly detected indeterminate nodule in persons 35 years of age or older. †Minimal or absent history of smoking and of other known risk factors. ‡History of smoking or of other known risk factors. From MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology, November 2005;237:395–400. Copyright 2005 Radiological Society of North America. |

||

Suggested Readings

Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, et al. Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2001;285:914–924.

Henschke C, McCauley D, Yahnkelevitz D, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project. Lancet 1999;354:99–105.

MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2005;237:395–400.

Midthun DE, Swensen SJ, Jett JR. Approach to the solitary pulmonary nodule. Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68:378–385.

Santambrogio L, Nosotti M, Bellaviti N, Pavoni G, Radice F, Caputo V. CT guided fine needle aspiration cytology of solitary pulmonary nodules: a prospective, randomized study of immediate cytologic evaluation. Chest 1997;112:423–425.

Siegelman SS, Zerhouni EA, Leo FP, et al. CT of the solitary pulmonary nodule. Am J Roentgenol 1980;135:1–13.

Toomes H, Delphendahl A, Manke H-G, Vogt-Moykopf I. The coin lesion of the lung. A review of 955 resected coin lesions. Cancer 1983;51:534–537.

Wallace JM, Deutsch AL. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy and percutaneous needle lung aspiration for evaluating the solitary pulmonary nodule. Chest 1982;81:665–671.

Zerhouni EA, Stitik FP, Siegelman SS, et al. CT of the pulmonary nodule: a cooperative study. Radiology 1986;160:319–327.