Chapter 29 Pulmonary Infections in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease

Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Pathophysiology

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection: Background

The immune dysregulation that arises from HIV infection means that bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa can all cause disease in patients with advanced infection. Box 29-1 shows the organisms that typically infect the lung in HIV disease. Of these, the agents of bacterial infections, tuberculosis, and PCP are the most important. In the West, 40% of diagnosed AIDS cases are due to PCP. This chapter provides a brief general overview of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of HIV infection, followed by a more detailed discussion of other important aspects of the disease and its infectious pulmonary complications.

Box 29-1

Etiologic Agents of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Related Pulmonary Infections

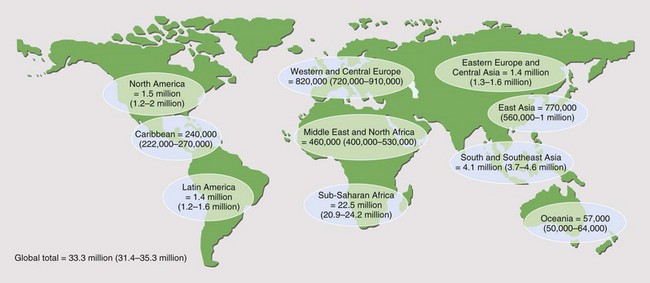

It is reported that by the end of 2009, 33.3 million people worldwide had acquired HIV infection (Figure 29-1). Of these, over 40% are thought to have developed AIDS (for definition of AIDS, see Tables 29-1 and 29-2 and Box 29-2). Globally, 2.6 million people acquired HIV infection in 2009, and 1.8 million died of AIDS. The developing world has been most affected. Sub-Saharan Africa is the current epicenter of the pandemic (accounting for two thirds of all infections); here, nearly 6% of adults are HIV-infected. South and Southeast Asia are responsible for almost a fifth of the estimated HIV global burden. In Central-Eastern Europe and Central Asia, there are currently 1.4 million HIV-infected persons. In the developed world, North America and Western Europe account for approximately 1.5 million and 820,000 infections, respectively. The vast majority of these are spread through sexual contact, although vertical (mother-to-child) and blood-borne infections are common. In the developing world, heterosexual transmission is the norm. In North America and Europe, men who have sex with men constitute the largest group of HIV-infected persons.

| Group | Infection |

|---|---|

| I | Acute primary |

| II | Asymptomatic |

| III | Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy |

| IV | Other disease |

| Subgroup A | Constitutional disease (e.g., weight loss >10% of body weight or >4.5 kg; fevers with temperatures >38.5° C for >1 month; diarrhea lasting >1 month) |

| Subgroup B | Neurologic disease (e.g., HIV encephalopathy, myelopathy, peripheral neuropathy) |

| Subgroup C | Secondary infectious diseases |

| Subgroup C1 | AIDS-defining secondary diseases (e.g., Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, cerebral toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus retinitis) |

| Subgroup C2 | Other specified secondary infectious diseases (e.g., oral candidiasis, multidermatomal varicella zoster) |

| Subgroup D | Secondary cancers (e.g., Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma) |

| Subgroup E | Other conditions (e.g., lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis) |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

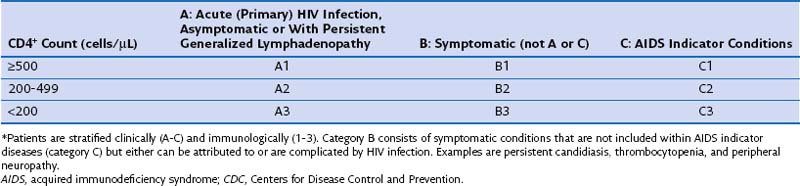

Table 29-2 CDC Classification System for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Clinical Categories*

Box 29-2

Adult AIDS Indicator Diseases*

Candidiasis of esophagus, trachea, bronchi, or lungs

Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

Cryptosporidiosis, with diarrhea for longer than 1 month

Cytomegalovirus disease (not in liver, spleen, or lymph nodes)

Encephalopathy caused by HIV (AIDS dementia complex)

Herpes simplex: ulcers for >1 month, or bronchitis, pneumonitis, esophagitis

Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Isosporiasis, with diarrhea for >1 month

Lymphoma: Burkitt, or immunoblastic, or primary in CNS

Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, any site (pulmonary or extrapulmonary)

Mycobacterial infections due to other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

Pneumonia recurrent within a 12-month period

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Natural History of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Chronic Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

The term AIDS was originally created as an epidemiologic tool to capture specific clinical presentations, which early in the HIV epidemic appeared to suggest significant immune deficiency. Over the past 30 years, the definition has been modified to incorporate the expanding spectrum of diseases affecting HIV-infected patients, including cervical carcinoma and recurrent bacterial pneumonia (see Box 29-2). The 1993 CDC classification included an immunologic criterion for AIDS (CD4+ count below 200 cells/µL or CD4+ percentage less than 14% of total lymphocytes) regardless of clinical symptoms (see Table 29-2). These data are used to define a point at which the risk for severe opportunistic infection rises dramatically.

Clinical Features

Bacterial Infection

Bronchiectasis

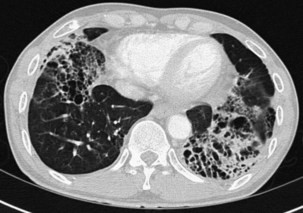

Bronchiectasis is increasingly recognized in HIV-infected patients with advanced HIV disease and low CD4+ lymphocyte counts. It probably arises secondary to recurrent bacterial, mycobacterial or P. jirovecii infections. The diagnosis most often is made by high-resolution (thin-section) computed tomography (CT) scanning (Figure 29-2). Its prevalence has not been accurately determined, although with improved survival from both opportunistic infections and HIV disease, it can be expected to be increasingly common in clinical practice. The pathogens isolated in patients with bronchiectasis are those seen in bronchitis. In addition, Burkholderia cepacia and Moraxella catarrhalis have been described.

Pneumonia

Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia occurs more frequently in HIV-infected patients than in the general population. It is especially common in HIV-infected injecting drug users. The spectrum of bacterial pathogens is similar to that in non–HIV-infected persons (see Box 29-1). S. pneumoniae is the most commonly identified pathogen, followed by H. influenzae. HIV-infected patients with S. pneumoniae–related pneumonia frequently are bacteremic. In one study, the rate of pneumococcal bacteremia in HIV-infected patients was 100 times that for an HIV-negative population. More recent work has confirmed this to be the case for all causes of HIV-related bacterial pneumonia. Typically, blood cultures have a 40-fold increased pick-up rate in HIV-positive patients. The widespread use of ART has led to some decrease in rates of bacterial pneumonia and bacteremia, although they are still considerably higher than in a non–HIV-infected population.

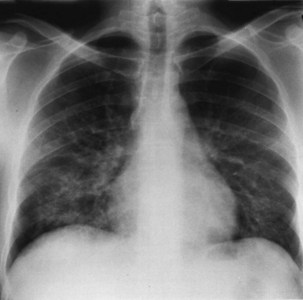

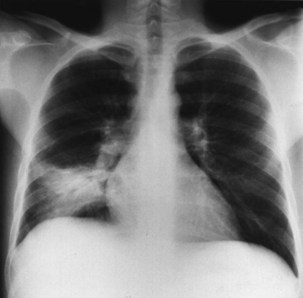

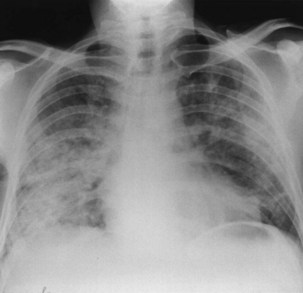

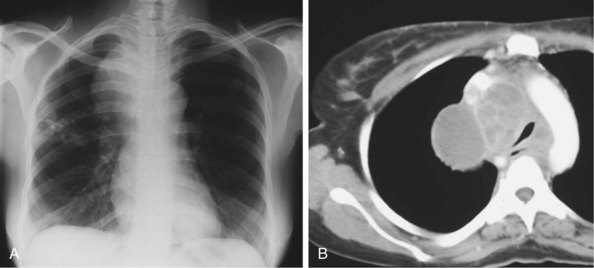

Bacterial pneumonia has a similar presentation in HIV-infected patients and in uninfected persons. Chest radiographs frequently are atypical in appearance, mimicking that in PCP in up to half of the cases (Figure 29-3). By contrast, radiographic lobar or segmental consolidation also may be seen in a wide range of bacterial organisms (Figure 29-4); these include S. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, H. influenzae, and M. tuberculosis. PCP also may manifest with lobar or segmental consolidation. In patients with more advanced HIV disease and low CD4+ lymphocyte counts, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus also can cause pneumonia.

Mycobacterial Infections

Tuberculosis

Pulmonary disease is the most common presentation, and clinical manifestations are determined by the patient’s level of immunity. For example, persons with reasonably well-preserved CD4+ counts exhibit clinical features similar to those of “normal” adult postprimary disease (Table 29-3). Signs and symptoms typically include weight loss, fever with sweats, cough, sputum, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain. These patients may have no clinical features to suggest associated HIV infection. The chest radiograph frequently shows upper lobe consolidation, and cavitary change is common (Figure 29-5). If performed, the tuberculin skin test (TST), using purified protein derivative (PPD), usually gives a positive result, and the likelihood that spontaneously expectorated sputum or BAL fluid will be smear-positive for acid-fast bacilli is high.

Table 29-3 Tuberculosis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection

| Diagnostic Feature | Stage of HIV Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Reasonable Immunity | Impaired Immunity | |

| Chest radiographic appearance | Upper zone infiltrates and cavities (cf postprimary infection) | Lymphadenopathy, effusions, miliary or diffuse infiltrates (cf primary infection) Normal |

| Sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage “smear-positive” | Frequently | Less commonly |

| Disease site | Localized | Widely disseminated |

| Tuberculin test–positive | Frequently | Less commonly |

In persons with advanced HIV disease (i.e., low CD4+ lymphocyte counts and clinically apparent immunosuppression), it may be difficult to diagnose tuberculosis. The clinical presentation here often is with nonspecific symptoms. Fever, weight loss, fatigue, and malaise may be mistakenly ascribed to HIV infection itself. In this context, pulmonary tuberculosis is often similar to primary infection, with the chest radiograph showing diffuse or miliary-type shadowing (Figure 29-6), hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy, or pleural effusion; cavitation is unusual, with no upper zone chest radiographic predominance. In up to 10% of patients, the chest radiograph may appear normal; in others, the pulmonary infiltrate can be bilateral, diffuse, and interstitial in pattern, thus mimicking PCP. Hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusion also may be manifestations of pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma or lymphoma, with which M. tuberculosis may coexist. The TST result usually is negative, and spontaneously expectorated sputum and BAL fluid samples often are smear-negative (although they are culture-positive).

In addition to pulmonary tuberculosis, extrapulmonary disease occurs in a high proportion of HIV-infected persons with low CD4+ lymphocyte counts (less than 150 cells/µL). Mycobacteremia and generalized lymph node infection (Figure 29-7) are common, but involvement of bone marrow, liver, pericardium, meninges, and brain also has been described.

Infections Due to Mycobacteria Other Than Tuberculosis

Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia

The clinical presentation of PCP is nonspecific, with onset of progressive exertional dyspnea over days or weeks, together with a dry cough, with or without expectoration of minimal quantities of mucoid sputum. Patients often report an inability to take a deep breath, which is not due to pleurisy (Table 29-4). Fever is common, yet patients rarely complain of temperature-related signs and symptoms including sweats. In HIV-infected patients, the presentation usually is more insidious than in those receiving immunosuppressive therapy. The median time to diagnosis from onset of symptoms is more than 3 weeks in those with HIV infection, compared with less than 1 week in non–HIV-infected patients. In a small proportion of HIV-positive patients, the disease course of PCP is fulminant, with an interval of only 5 to 7 days between onset of symptoms and progression to development of respiratory failure. In others, it may be much more indolent, with respiratory symptoms that worsen almost imperceptibly over several months. Rarely, PCP may manifest as a fever of undetermined origin without respiratory symptoms.

Table 29-4 Clinical Presentation in Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia

| Examination | Typical Presentation | Atypical Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Progressive exertional dyspnea over days or weeks | Sudden onset of dyspnea over hours or days |

| Dry cough ± mucoid sputum | Cough productive of purulent sputum Hemoptysis |

|

| Difficulty taking in a deep breath not related to pleuritic pain | Chest pain (pleuritic or “crushing”) | |

| Fever ± sweats Tachypnea |

||

| Signs | Normal breath sounds or fine end-inspiratory basal crackles | Wheeze, signs of focal consolidation or pleural effusion |

| Chest radiographic appearance | Early: perihilar “haze,” or bilateral interstitial shadowing | Pleural effusion, lobar or segmental consolidation |

| Late: alveolar-interstitial changes or “whiteout” (marked alveolar consolidation with sparing of apices and costophrenic angles) | ||

| Arterial blood gases | PaO2: early: normal; late: low | |

| PaCO2: early: normal or low; late: normal or high |

Clinical examination usually is remarkable only for the absence of physical signs; occasionally, fine, basal, end-inspiratory crackles are audible. Features that would suggest an alternative diagnosis include a cough productive of purulent sputum or hemoptysis, chest pain (particularly pleural pain), and signs of focal consolidation or pleural effusion (see Table 29-4). Of note, infection with more than one pathogen occurs in almost one fifth of these patients, so symptoms may be related to infection with any of several agents.

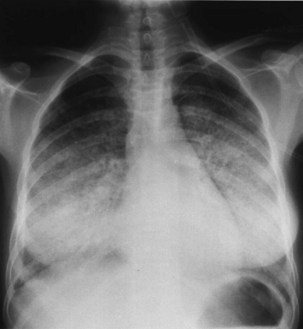

The chest radiographic appearance in PCP typically is unremarkable initially. Later, diffuse reticular shadowing, especially in the perihilar regions, is seen and may progress to widespread alveolar consolidation that resembles that in untreated pulmonary edema or with presentation late in disease. At this stage, the lung may be grossly consolidated and almost airless (Figure 29-8). Up to 20% of chest radiographs are atypical in appearance, showing lobar consolidation, honeycomb lung, multiple thin-walled cystic air spaces (pneumatoceles), intrapulmonary nodules, cavitary lesions, pneumothorax, and hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Predominantly apical changes, resembling those of tuberculosis, may occur in patients with PCP that developed subsequent to anti–P. jirovecii prophylaxis with nebulized pentamidine (Figure 29-9). All of these radiographic changes are nonspecific; similar changes occur with other pulmonary pathogens, including pyogenic bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal infection, as well as Kaposi sarcoma and nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis. Respiratory symptoms in an immunosuppressed, HIV-infected patient with a normal-appearing chest radiograph should not be discounted, however, because radiographic abnormalities may not appear until 2 to 3 days later.

Fungal Infections

Aspergillus Infection

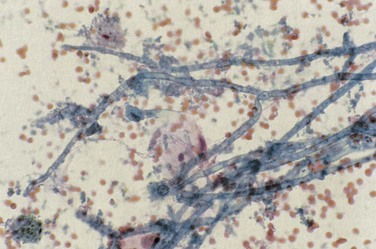

Patterns of pulmonary disease include cavitating upper lobe disease, focal radiographic opacities resembling bacterial pneumonia, bilateral diffuse and patchy opacities (nodular or reticular-nodular in pattern), pseudomembranous aspergillosis (which may obstruct the lumen of airways), and tracheobronchitis. Diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis is made by the identification of fungus in sputum, sputum casts, or BAL fluid in association with respiratory tract tissue invasion (Figure 29-10). Serum (1,3)-β-D-glucan levels may be elevated (see further on).

Cryptococcal Infection

Infection may manifest in one of two ways: either as primary cryptococcosis or complicating cryptococcal meningitis as part of disseminated infection with cryptococcemia, pneumonia, and cutaneous disease (umbilicated papules mimicking molluscum contagiosum) (Figure 29-11). Primary pulmonary cryptococcosis presents in a very nonspecific way and is frequently indistinguishable from other pulmonary infections. In disseminated infection, the presentation frequently is overshadowed by headache, fever, and malaise (caused by meningitis). The time to onset may range from only a few days to several weeks. Examination may reveal skin lesions, lymphadenopathy, and meningism. In the chest, signs may be absent or crackles may be audible. Arterial blood gas analysis may reveal normal findings or show hypoxemia. The most common abnormality on the chest radiograph is focal or diffuse interstitial infiltrates. Less frequently, masses, mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy, nodules, and effusion are noted.

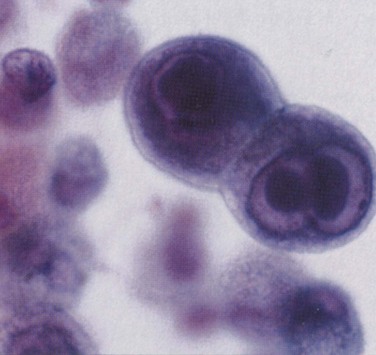

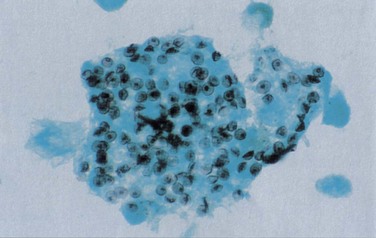

The diagnosis of cryptococcal pulmonary infection (Figure 29-12) is made by identification of Cryptococcus neoformans (by staining with India ink or mucicarmine, and by culture) in sputum, BAL fluid, pleural fluid, or lung biopsy tissue. Cryptococcal antigen may be detected in serum using the cryptococcal latex agglutination (CrAg) test. Titers usually are high but may be negative in primary pulmonary cryptococcosis, in which case BAL fluid (CrAg) is positive. In patients with disseminated infection, C. neoformans also may be cultured from blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

Endemic Mycoses

Histoplasmosis

Progressive, disseminated histoplasmosis in patients with HIV typically manifests with a subacute onset of fever and weight loss; approximately 50% of patients have mild respiratory symptoms with a nonproductive cough and dyspnea. Hepatosplenomegaly frequently is noted on examination, and a rash (similar to that produced by Cryptococcus spp.) may be seen. Rarely, the presentation may be rapidly fulminant, with clinical features of the sepsis syndrome including anemia or disseminated intravascular coagulation. The chest radiograph may be normal in appearance (in up to one third of patients), although characteristic abnormalities consist of bilateral, widespread nodules 2 to 4 mm in size (Figure 29-13). Other radiographic features are nonspecific and include interstitial infiltrates, reticular nodular shadowing, and alveolar consolidation. The diagnosis is made reliably by identification of the organism in Wright-stained peripheral blood or by Giemsa staining of bone marrow, lymph node, skin, sputum, BAL fluid, or lung tissue. It is important that identification be confirmed by detection of H. capsulatum var. capsulatum polysaccharide antigen by radioimmunoassay, which has a high sensitivity. False-positive results are possible in patients infected with Blastomyces and Coccidioides spp. Testing for Histoplasma antibodies by complement fixation or immunodiffusion techniques may give a negative result in immunosuppressed, HIV-positive patients. Serum (1,3)-β-D-glucan levels may be elevated (see further on).

Viral Infections

Community-Based Respiratory Viral Infections

Influenza A

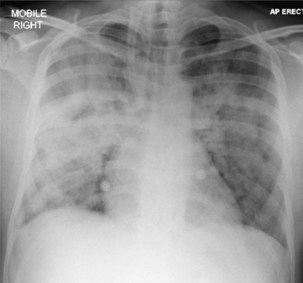

HIV-infected patients with seasonal or H1N1 influenza typically present with an acute respiratory illness (e.g., coryzal symptoms) with fever, headache, and myalgia. Vomiting and diarrhea occur more often with H1N1 influenza than with seasonal influenza. Some patients with seasonal or H1N1 influenza may not have fever. Careful clinical assessment, together with awareness of local surveillance data on circulating influenza viruses and other community-prevalent respiratory pathogens, is important in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with an influenza-like illness. In some HIV-infected patients, especially those with low CD4+ cell counts (less than 100 cells/µL), the illness may progress rapidly (Figure 29-14) and can be complicated by secondary bacterial pneumonia. The diagnosis is made by detection of viral antigen or RNA, or by culture of nasopharyngeal aspirate or nasal swab.

Cytomegalovirus Infection

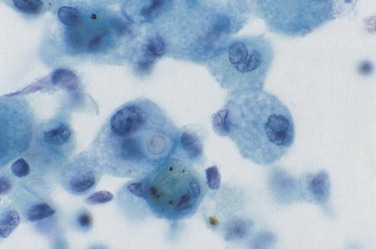

In patients in whom CMV is the sole identified pathogen, clinical presentation and chest radiographic abnormalities (usually diffuse interstitial infiltrates) are nonspecific. Diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis is made by identifying characteristic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions, not only in cells in BAL fluid but also in lung biopsy specimens (Figure 29-15).

Protozoal Infections

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii infection in HIV-infected patients usually occurs as a result of reactivation of latent, intracellular protozoa acquired in a primary infection. Toxoplasmic pneumonia frequently manifests with nonproductive cough and dyspnea. Chest radiographic abnormalities include diffuse interstitial infiltrates indistinguishable from those of PCP (Figure 29-16), as well as micronodular infiltrates, a coarse nodular infiltrate, cavitary change, and lobar consolidation. The diagnosis is made by hematoxylin-eosin or Giemsa staining of BAL fluid, which reveals cysts and trophozoites of T. gondii. Staining of BAL fluid is not always positive; the diagnostic yield is increased either by staining of transbronchial biopsy material or by performing PCR assay to detect T. gondii DNA in BAL fluid.

Strongyloidiasis

The nematode Strongyloides stercoralis is endemic in warm countries worldwide. In immunosuppressed patients, the organism has an increased ability to reproduce parthenogenetically in the gastrointestinal tract without the need for repeated exposure to new infection—so-called autoinfection. This enhanced reproductivity results in a great increase in worm load, and a hyperinfective state ensues; massive acute dissemination with S. stercoralis may occur in the lungs, kidneys, pancreas, and brain. Although infection with S. stercoralis is more severe in immunocompromised patients, it is no more common in patients who have HIV infection. Presentation with hyperinfection may be with fever, hypotension secondary to bacterial sepsis, or disseminated intravascular coagulation. The clinical features of respiratory S. stercoralis infection are very nonspecific. S. stercoralis in sputum or BAL fluid (Figure 29-17) may be identified in HIV-positive patients in the absence of symptoms elsewhere; this can predate disseminated infection and as such requires prompt treatment.

Diagnosis

It is apparent from the foregoing discussion that HIV-related pneumonias of any cause may present in a very similar manner. A wide range of investigations are available to aid diagnosis. These are listed in Box 29-3. If the subject is producing sputum, it is important to obtain samples for bacterial and mycobacterial detection. In up to one third of cases, these will assist in diagnosis. Obtaining three samples on consecutive days (preferably either with overnight or early morning production) is the crucial first step in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. This is considerably easier and safer for health care personnel than obtaining hypertonic saline–induced sputum or BAL fluid. Blood cultures also are important, because very high rates of bacteremia have been reported in both bacterial and mycobacterial disease (see earlier).

Box 29-3

Tests Available to Aid Diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection–Related Pneumonia

Histopathologic

Serologic studies (antigen or antibody testing)

Serum lactate dehydrogenase measurement

Microscopy and culture of body fluid/tissue (e.g., sputum, blood, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, lung tissue) obtained by:

Nucleic acid detection of specific organisms (e.g., by polymerase chain reaction assay for Pneumocystis jirovecii in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or induced sputum)

Computed Tomography Scanning

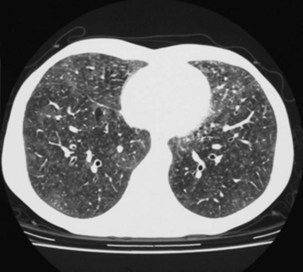

High-resolution (thin-section) CT scanning of the chest may be helpful when the chest radiographic appearance is normal, unchanged, or equivocal. The characteristic appearance of an alveolitis (i.e., areas of ground glass attenuation through which the pulmonary vessels can be clearly identified) may be present, which indicates active pulmonary disease (Figure 29-18). This feature, however, is neither sensitive nor specific for PCP, although its sensitivity can be improved if evidence for reticulation or small cystic lesions is added. Hence, a negative test result implies an alternative diagnosis.

Biochemical Assays

Serum (1,3)-β-D-Glucan

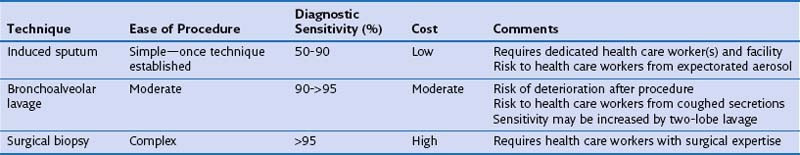

From the preceding discussion, it is evident that noninvasive tests cannot reliably distinguish the different infecting agents from each other but may be useful in excluding acute opportunistic disease. Thus, the clinician is left with either proceeding to diagnostic lung fluid or tissue sampling (using either induced sputum collection or bronchoscopy and BAL with or without transbronchial biopsy) (Table 29-5) or treating an unknown condition empirically. ART also has altered the investigation of respiratory disease. The numbers of invasive procedures performed are falling, and such procedures tend to be used in patients not taking antiretroviral drugs (usually to exclude PCP), or in whom no response to empirical antibiotic therapy (regardless of the CD4+ count) has been observed.

Induced Sputum

Spontaneously expectorated sputum is inadequate for diagnosis of PCP. Sputum induction by inhalation of ultrasonically nebulized hypertonic saline may provide a suitable specimen (see Table 29-5). The technique requires close attention to detail and is much less useful when samples are purulent. Sputum induction must be carried out away from other immunosuppressed patients and health care workers, ideally in a room with separate negative-pressure ventilation, to reduce the risk of nosocomial transmission of tuberculosis. Although very specific (at a rate greater than 95%), the sensitivity of induced sputum varies widely (55% to 90%), and therefore a negative result for P. jirovecii prompts further diagnostic studies. The use of immunofluorescence staining enhances the yield of induced sputum compared with standard cytochemistry.

Bronchoscopy

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with BAL commonly is used to diagnose HIV-related pulmonary disease. When a good “wedged” sample is obtained, the test has a sensitivity of greater than 90% for detection of P. jirovecii (Figure 29-19). Just as with induced sputum, fluorescent staining methods increase the diagnostic yield, which makes bronchoscopy the procedure of choice in most centers. More technically demanding (both of the patient and of the operator) than induced sputum collection, bronchoscopy and BAL have the advantage that direct inspection of the upper airway and bronchial tree can be performed and, if necessary, biopsy specimens taken. Transbronchial biopsy may marginally increase the diagnostic yield of the procedure. This is relevant for the diagnosis of mycobacterial disease, although the relatively high complication rate in HIV-infected persons (pneumothorax and the possibility of significant pulmonary hemorrhage in up to 10%) outweighs the advantages of the technique for routine purposes.

Treatment

Treatment of Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia

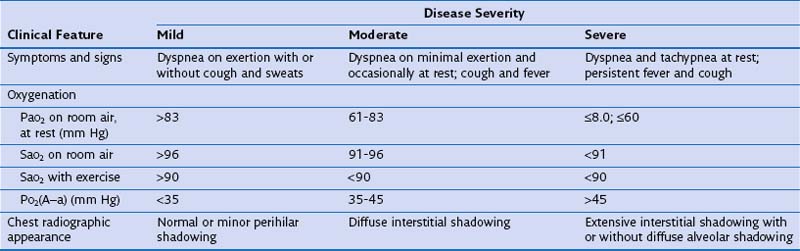

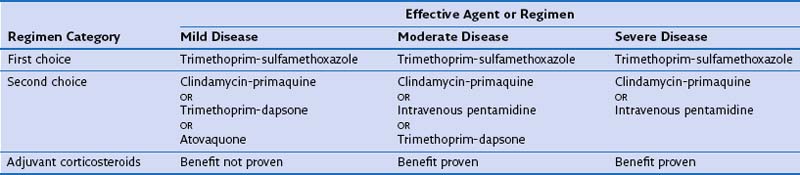

Before institution of treatment, assessment of the severity of PCP should be performed, to include a thorough history, physical examination, arterial blood gas analysis, and chest radiography. On the basis of the findings, patients can then be stratified into those with mild, moderate, or severe disease (Table 29-6). This classification is important, because some drugs are of unproven benefit and others are known to be ineffective for the treatment of severe disease. In addition, adjuvant glucocorticoid therapy may be given to patients with moderate or severe pneumonia. Before (or as soon as feasible after) starting therapy with TMP-SMX, dapsone, or primaquine, patients should be tested for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, because these drugs increase the risk of hemolysis.

Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole

Several drugs are effective in the treatment of PCP. TMP-SMX is the drug of first choice (Tables 29-7 and 29-8). Overall, it is effective in 70% to 80% of patients when used for first-line therapy. Adverse reactions to TMP-SMX are common and usually become apparent between days 6 and 14 of treatment. Neutropenia and anemia (in up to 40% of patients), rash and fever (up to 30%), and biochemical abnormalities of liver function (up to 15%) are the most frequent adverse reactions. Hematologic toxicity induced by TMP-SMX is neither attenuated nor prevented by coadministration of folic or folinic acid. Furthermore, the use of these agents may be associated with reduced therapeutic success. During treatment with TMP-SMX, monitoring with full blood counts, liver function testing, and measurements of urea and electrolytes at least twice weekly is indicated.

Table 29-8 Treatment Schedules for Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia*

| Drug | Dosage | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) | Trimethoprim 15-20 mg/kg IV q24h plus sulfamethoxazole 75-100 mg/kg IV daily in divided doses, q6h or q8h | Give IV for moderate to severe disease, can change to oral formulation after clinical improvement |

| Same daily dose of TMP-SMX as above, given in divided doses q8h for 21 days | Given for mild disease | |

| OR | ||

| 1920 mg (two TMP-SMX double-strength tablets) PO q8h for 21 days | ||

| Clindamycin-primaquine | Clindamycin 600-900 mg IV q6h-q8h plus primaquine 15-30 mg PO q24h for 21 days | Methemoglobinemia less likely if primaquine dose of 15 mg PO q24h is used |

| OR | ||

| Clindamycin 300-450 mg PO q6h-q8h plus primaquine 15-30 mg PO q24h for 21 days | ||

| Pentamidine | 4 mg/kg IV q24h for 21 days | Diluted in 250 mL of 5% dextrose in water and infused over 60 minutes 3 mg/kg IV q24h for 21 days used by some clinicians to reduce toxicity |

| Trimethoprim-dapsone | Trimethoprim 15 mg/kg PO q24h in divided doses q8h plus dapsone 100 mg PO q24h for 21 days | |

| Atovaquone | 750 mg PO q12h for 21 days | Give with food to increase absorption |

| Glucocorticoids | Prednisolone 40 mg PO q12h on days 1-5, then 40 mg PO q24h on days 6-10, then 20 mg PO q24h on days 11-21 | Regimen recommended by CDC/NIH/IDSA; widely used in United States |

| OR | ||

| Methylprednisolone IV at 75% of dose given above for prednisolone | ||

| Methylprednisolone 1 g IV q24h on days 1-3, then 0.5 g IV q24h on days 4-6, then prednisolone 40 mg PO q24h, tapered to 0 over days 7-16 | Regimen widely used in United Kingdom |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH, National Institutes of Health; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America.

* NOTE: None of these regimens for adjuvant glucocorticoids therapy have been compared in prospective clinical trials.

Other Therapeutic Agents

If treatment with TMP-SMX fails, or is not tolerated by the patient, several alternative therapies are available (see Tables 29-7 and 29-8).

Atovaquone

Atovaquone is licensed for the treatment of mild and moderate-severity PCP in patients who are intolerant of TMP-SMX. In tablet formulation (no longer available), this drug was less effective but was better tolerated than TMP-SMX or intravenous pentamidine for treatment of mild or moderate-severity PCP (see Tables 29-7 and 29-8). There are no data from prospective studies that compare the liquid formulation (which has better bioavailability) with other treatment regimens. Common adverse reactions include rash, fever, nausea and vomiting, and constipation. Absorption of atovaquone is increased if it is taken with food.

Intravenous Pentamidine

Intravenous pentamidine is now seldom used for the treatment of mild or moderate-severity PCP because of its toxicity. Intravenous pentamidine may be used in patients who have severe PCP, despite its toxicity, if other agents have failed (see Tables 29-7 and 29-8). Nephrotoxicity develops in almost 60% of patients given intravenous pentamidine (indicated by elevation in serum creatinine), leukopenia develops in approximately half, and up to 25% have symptomatic hypotension or nausea and vomiting. Hypoglycemia occurs in approximately 20% of patients. Because of the long half-life of the drug, this effect may emerge up to several days after the discontinuation of treatment. Pancreatitis also is a recognized side effect.

Adjuvant Glucocorticoids

For patients who have moderate and severe PCP, adjuvant glucocorticoid therapy reduces the risk of respiratory failure by up to half, and the risk of death by up to one third (see Tables 29-7 and 29-8). Glucocorticoids are given to HIV-infected patients with confirmed or suspected PCP who have a PaO2 less than below 70 mm Hg or a PO2(A−a) greater than greater than 33 mm Hg. Oral or intravenous adjunctive therapy is given at the same time as (or within 72 hours of starting) specific anti–P. jirovecii therapy. Clearly, in some patients treatment is commenced on a presumptive basis, pending confirmation of the diagnosis. If glucocorticoids are started at a later time, the benefits are less clear, although most clinicians would use these agents in patients with moderate or severe PCP. In prospective studies, adjuvant glucocorticoids have not been shown to be of benefit in patients with mild PCP. However, it would be difficult to demonstrate this, given that survival in such cases approaches 95% with standard treatment.

Deterioration in the Patient with Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia

Deterioration in a patient who is receiving anti–P. jirovecii therapy may occur for several reasons (Table 29-9). Before deterioration is ascribed to treatment failure necessitating a change in therapy, these alternatives should be evaluated carefully. It also is important to consider treating for any copathogens present in BAL fluid and to perform bronchoscopy if the diagnosis was made empirically, and to repeat the procedure or carry out open lung biopsy to confirm that the diagnosis is correct.

Table 29-9 Causes of Clinical Deterioration in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Infected Patient with Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia

| Cause | Comments |

|---|---|

| Severe progressive pneumonia | |

| Side effects of therapy |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; PCP, Pneumocystis pneumonia.

Treatment of Mycobacterial Diseases

Treatment of Tuberculosis

Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome

IRIS develops in up to one third of HIV-infected patients being treated for tuberculosis when ART is started. The median time to onset of tuberculosis-related IRIS is about 4 weeks from beginning antituberculosis treatment or 2 weeks from commencing ART. It appears to be more likely in patients who have disseminated tuberculosis (and hence presumably more stimulating antigen present as well as more potential for significant inflammatory reactions); and a lower baseline blood CD4+ count. A rapid fall in HIV load as well as a large increase in CD4+ counts in response to ART may also predict IRIS; as might circulating inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ or markers such as C-reactive protein. The relationship between early use of ART and low blood CD4+ counts suggests that care must be taken when antiretrovirals are started in patients with tuberculosis at sites where rapid expansion of an inflammatory mass could be life-threatening. Examples of this are cerebral, pericardial, or peritracheal disease (Figure 29-20).

An important point is that IRIS currently is a diagnosis of exclusion. No specific laboratory test is available to assist with this, and it should be made only after progressive or (multi)drug-resistant tuberculosis, poor drug adherence (to either antituberculosis or antiretroviral agents) and drug absorption, or an alternative pathologic process has been excluded as an explanation for the presentation. Criteria have been drawn up that seek to provide clinical diagnostic guidelines (Box 29-4).

Box 29-4

Diagnostic Criteria for Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Infected Patients with Tuberculosis

Evidence Supporting Diagnosis

1. Initial diagnosis of tuberculosis confirmed by laboratory methods or by appropriate response to treatment

2. Development of new clinical phenomena temporally associated with start of ART, including but not limited to:

3. Immune restoration (e.g., a rise in CD4+ lymphocyte count in response to ART)

Alternative Diagnoses to Be Excluded

Progressive underlying infection

Treatment failure due to drug resistance (MDR or XDR)

Treatment failure from poor adherence

Comorbidity—another, coexistent diagnosis (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphoma)

ART, antiretroviral treatment; MDR, multidrug-resistant; XDR, extensively drug-resistant.

Treatment of Fungal Infections

The treatment regimens for fungal infections complicating HIV infection are shown in Table 29-10.

Table 29-10 Treatment of Fungal Pulmonary Infection in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Infected Patients

| Infectious Agent | Drug | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus spp. | Voriconazole 6 mg/kg IV q12h on day 1, then 4 mg/kg IV q12h, then 200 mg PO q12h | Change to oral therapy once evidence of clinical recovery |

| OR Liposomal amphotericin 5 mg/kg IV q24h |

Use for severely ill patients, monitor renal function | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Liposomal amphotericin 4-6 mg/kg IV q24h plus | Monitor renal function |

| Flucytosine 50 mg/kg IV q6h for 2-4 weeks | Monitor blood count, liver and renal function | |

| OR Fluconazole 300-400 mg PO q12h for 2-4 weeks |

||

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Liposomal amphotericin 3 mg/kg IV q24h , then itraconazole 200 mg PO q8h for 3 days, then 200 mg PO q12h | Use for severely ill patients Monitor renal function Change to oral therapy after 2 weeks or after clinical improvement obtained Monitor itraconazole levels |

| Itraconazole 200 mg PO q8h for 3 days, then 200 mg PO q12h for 6-12 weeks | Use for less severely unwell patients Monitor itraconazole levels |

|

| Coccidioides immitis | Amphotericin B 0.5-1 mg/kg q24h for 2-4 weeks OR Liposomal amphotericin 4 mg/kg IV q24h for 2-4 weeks |

Monitor renal function |

| Penicillium marneffei | Liposomal amphotericin 3 mg/kg IV q24h for 2 weeks, THEN Itraconazole 400 mg PO q24h for 10 weeks |

Use for severely ill patients Monitor renal function Monitor itraconazole levels |

| Itraconazole 400 mg PO q24h for 4-6 weeks | Use for mild disease Monitor itraconazole levels |

Treatment of Parasitic Infections

The treatment regimens are shown in Table 29-11.

Table 29-11 Treatment of Parasitic Infections in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Infected Patients

| Infectious Agent | Drug | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Toxoplasma gondii | ||

| First choice | Sulfadiazine 1-1.5 g PO q6h plus pyrimethamine 200 mg PO q24h on day 1, then 50 mg (in patients weighing <60 kg) or 75 mg (in patients weighing >60 kg) plus folinic acid 15 mg PO q24h for 14-28 days | Rash and fever are common |

| Second choice | Clindamycin 600 mg PO or IV q6h plus pyrimethamine and folinic acid (doses as above) for 14-28 days | If diarrhea develops, analyze stool for Clostridium difficile |

| Leishmania spp. | ||

| First choice | Liposomal amphotericin B 2-4 mg/kg IV q24h for 10 days | |

| Second choice | Sodium stibogluconate 20 mg/kg IV or IM q24h for 3-4 weeks | |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | Ivermectin 200 µg/kg PO q24h for 4 doses over 16 days |

Toxoplasmosis

A combination of sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine is the regimen of choice for T. gondii infection. The most frequent dose-limiting side effects are rash and fever. Adequate hydration must be maintained to avoid the risk of sulfadiazine crystalluria and obstructive uropathy. Alternative regimens are given in Table 29-11. Once treatment is completed, lifelong maintenance is necessary to prevent relapse, unless ART achieves adequate immune restoration (blood CD4+ count above 250 cells/µL and undetectable HIV load).

Clinical Course and Prevention

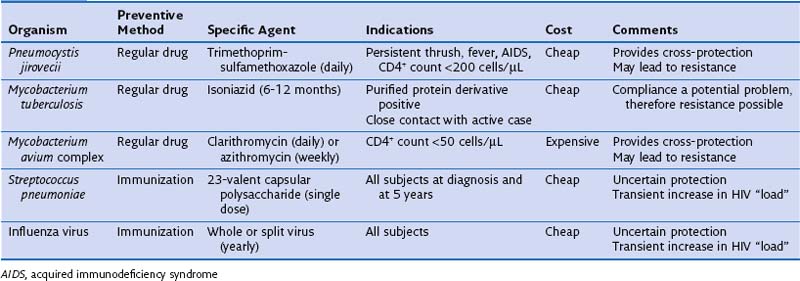

It has become apparent that specific infection prophylaxis also may confer protection against other agents. This “cross-prophylaxis” is seen particularly with the use of TMP-SMX for PCP which also provides cover against cerebral toxoplasmosis and several common bacterial infections (although not those caused by S. pneumoniae), and with use of macrolides for MAC infection, which further reduces the incidence of bacterial disease and also PCP. Use of large amounts of antibiotic raises the possibility of future widespread drug resistance. This concern clearly is of clinical import, and recent reports suggest that indeed in some parts of the world, the incidence of pneumococcal TMP-SMX resistance is rising. Current preventive therapies pertinent to lung disease focus on P. jirovecii, MAC, M. tuberculosis, and certain bacteria (Table 29-12).

Table 29-12 Prevention of Respiratory Infections in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Infected Adults

Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia Prophylaxis

Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole

As with treatment strategies, TMP-SMX is the drug of choice for prophylaxis of PCP (Table 29-13). It has the advantages of being highly effective for both primary and secondary prophylaxis (with the 1-year risk of PCP during therapy with this agent being 1.5% and 3.5%, respectively). It is cheap, can be taken orally, acts systemically, and provides some cross-prophylaxis against other infections, such as toxoplasmosis and infections due to Salmonella spp., staphylococci, and H. influenzae. Its main disadvantage is that adverse reactions are common (see earlier), occurring in up to 50% of patients taking the prophylactic dose.

Table 29-13 Primary and Secondary Prophylaxis Regimens for Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia

| Drug | Dose | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 1 double-strength* tablet PO q24h | Other options for primary prophylaxis: 1 double-strength* tablet PO q24h 3×/week OR 1 single-strength† tablet PO q24h Protects against toxoplasmosis and certain bacteria |

| Dapsone | 100 mg PO q24h | With pyrimethamine (25 mg PO q24h 3×/week) Protects against toxoplasmosis |

| Pentamidine | 300 mg given by Respirgard II (jet) nebulizer every 4 weeks | Less effective in subjects with CD4+ <100 cells/µL Provides no cross-prophylaxis |

| Atovaquone | 750 mg PO q12h | Absorption increased if administered with food Protects against toxoplasmosis |

* 160 mg trimethoprim plus 800 mg sulfamethoxazole.

Prognosis

Pneumocystis Jirovecii Pneumonia

Several clinical and laboratory features have prognostic significance in HIV-infected patients with PCP (Box 29-5). Severity scores based on the patient’s age, use of injection drugs, serum albumin, serum bilirubin, and PO2(A−a), or the patient’s age, hemoglobin, PaO2, presentation with a second or third episode of PCP, the presence of medical comorbidity and of pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma can predict survival reasonably accurately, with the highest scores indicating the worst outcome. In the era of ART the mortality from an episode of PCP is approximately 10%.

Box 29-5

Prognostic Factors Associated with Poor Outcome in Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia

On Hospital Admission

No previous knowledge of HIV serostatus

Tachypnea (respiratory rate higher than 30 breaths/minute)

Second or subsequent episode of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

Poor oxygenation: PaO2 <53 mm Hg or PO2(A−a) >30 mm Hg

Peripheral blood leukocytosis (>10.8 × 109/L)

Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase levels (>300 IU/L)

Elevated C-reactive protein level

Marked chest radiographic abnormalities: diffuse bilateral interstitial infiltrates with or without alveolar consolidation

Medical comorbid or other coexistent condition (e.g., pregnancy)

Controversies and Pitfalls

Crothers K, Thompson BW, Burkhardt K, et al. Lung HIV Study: HIV-associated lung infections and complications in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:275–281.

Huang L, Cattamanchi A, Davis JL, et al. International HIV-Associated Opportunistic Pneumonias (IHOP) Study; Lung HIV Study: HIV-associated Pneumocystis pneumonia. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:294–300.

Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Institutes of Health; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America: Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-4):1–207.

Morris A, Crothers K, Beck JM, Huang L. American Thoracic Society Committee on HIV Pulmonary Disease: An official ATS workshop report: emerging issues and current controversies in HIV-associated pulmonary diseases. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:17–26.

Pozniak AL, Coyne KM, Miller RF, et al. BHIVA Guidelines Subcommittee: British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of TB/HIV coinfection 2011. HIV Med. 2011;12:517–524.