Pulmonary Embolism

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with pulmonary embolism.

• Describe the causes of pulmonary embolism.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with pulmonary embolism.

• Describe the general management of pulmonary embolism.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

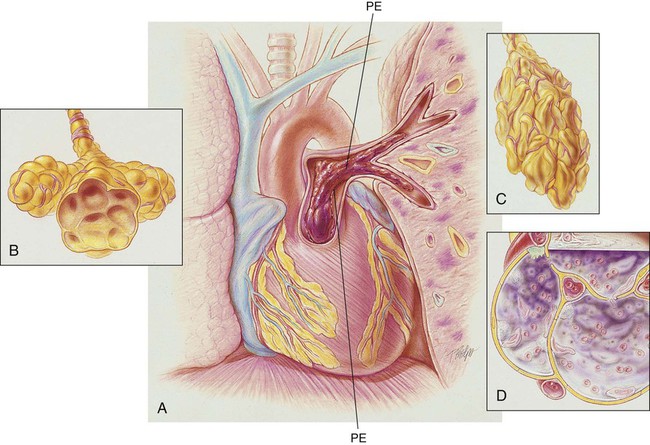

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

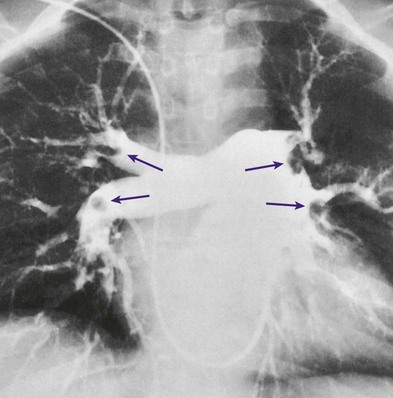

An embolus may originate from one large thrombus or occur as a shower of small thrombi and may or may not interfere with the right side of the heart’s ability to perfuse the lungs adequately. When a large embolus detaches from a thrombus and passes through the right side of the heart, it may lodge in the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery, where it forms what is known as a saddle embolus (partially shown in Figure 20-1). This is often fatal.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Although there are many possible sources of pulmonary emboli (e.g., fat, air, amniotic fluid, bone marrow, tumor fragments), blood clots are by far the most common. Most pulmonary blood clots originate—or break away from—sites of deep venous thrombosus (DVT) in the lower part of the body (i.e., the leg and pelvic veins and the inferior vena cava). When a thrombus or a piece of a thrombus breaks loose in a deep vein, the blood clot (now called an embolus) is carried through the venous system to the right atrium and ventricle of the heart and ultimately lodges in the pulmonary arteries or arterioles. There are three primary factors, known as Virchow’s triad, associated with the formation of DVT. Virchow’s triad includes (1) venous stasis (i.e., slowing or stagnation of blood flow through the veins), (2) hypercoagulability (i.e., the increased tendency of blood to form clots), and (3) injury to the endothelial cells that line the vessels. Box 20-1 provides common risk factors for pulmonary embolism.

Diagnosis and Screening

Depending on how much of the lung is involved, the size of the embolism, and the overall health of the patient, the signs and symptoms of a pulmonary embolism can vary greatly. Box 20-2 provides common signs and symptoms that often justify additional—and sometimes urgently needed—diagnostic procedures used to diagnose a suspected pulmonary embolism. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can dramatically reduce the mortality and morbidity of the disease.

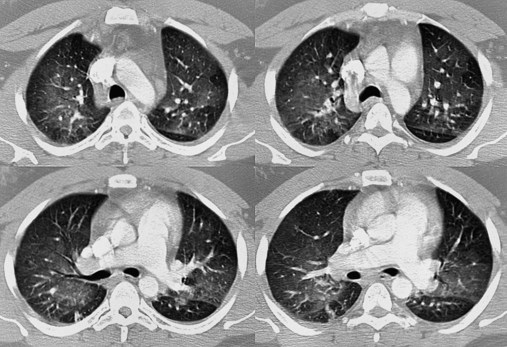

Spiral (Helical) Computed Tomography Scan

The spiral or helical computed tomography (CT) scan (pulmonary embolism CT scan) is fast becoming the first-line test for diagnosing suspected pulmonary embolism (Figure 20-2). Because the spiral CT scanner rotates continuously around the body, it can provide a three-dimensional image of any abnormalities with a higher degree of accuracy. A dye (contrast medium) is usually used to help visualize the structures of the lungs. It only takes about 20 seconds as opposed to 20 minutes for the standard CT scan. Because the spiral CT scan is fast, it is easier to capture the dye while it is still in the pulmonary arteries. The spiral CT scan exposes the patient to more radiation than the standard x-ray examination but increases the risk of an allergic reaction to the contrast medium (rare). The spiral CT scan is considered to be more sensitive than the ventilation-perfusion scan ( scan) and pulmonary angiogram, discussed later.

scan) and pulmonary angiogram, discussed later.

General Management of Pulmonary Embolism

Preventive Measures

Directions to patients at high risk for thromboembolic disease include the following:

• Walking—If possible, walk frequently. When riding in a car, stop often to walk around or perform a few deep knee bends. When flying in an airplane, move around the cabin every hour or so.

• Exercise while seated—When sitting, flex, extend, and rotate your ankles or press your feet against the seat in front of you. Try rising up and down on your toes. Avoid sitting with your legs crossed.

• Drink fluids—Drink plenty of water to avoid dehydration, which can contribute to the formation of blood clots. Avoid alcohol, which also contributes to fluid loss.

• Graduated compression stockings—Tight-fitting elastic stockings squeeze the patient’s legs, helping the veins and leg muscles move blood more efficiently. They provide a safe, simple, and inexpensive way to keep blood from stagnating. Research has shown that compression stockings used in combination with heparin are much more effective than heparin alone.

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. The hypoxemia that develops with pulmonary emboli usually is caused by wasted (dead space) ventilation. Hypoxemia caused by dead space ventilation is generally refractory to oxygen therapy (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

O No remarkable respiratory distress noted. Vital signs: BP 115/75, HR 75, RR 12; afebrile; tenderness over left shoulder and left anterior chest area; normal vesicular breath sounds; CXR: normal; ABGs (partial rebreathing mask): pH 7.40, Paco2 41,  24, Pao2 504 mm Hg; Spo2 97%.

24, Pao2 504 mm Hg; Spo2 97%.

P Reduce oxygen therapy per protocol (2 L/min by nasal cannula). Recheck Spo2.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I feel awful. I’m short of breath and lightheaded.”

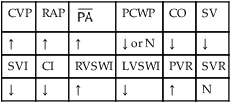

O Cyanosis; agitation; dyspnea; cough productive of small amount of blood-tinged sputum; vital signs: BP 90/45, HR 125, RR 30, T 37.2° C (99° F), slight wheezing throughout both lung fields; pleural friction rub, right midlung; ECG: varies among normal sinus rhythm, sinus tachycardia, atrial flutter. Hemodynamic indices: increased CVP, RAP,  , RVSWI, and PVR and decreased PCWP, CO, SV, SVI, and CI. CXR: atelectasis and consolidation in the right middle lobe. On Fio2 = 0.5, ABGs: pH 7.53, Paco2 26,

, RVSWI, and PVR and decreased PCWP, CO, SV, SVI, and CI. CXR: atelectasis and consolidation in the right middle lobe. On Fio2 = 0.5, ABGs: pH 7.53, Paco2 26,  21, Pao2 53; Spo2 89%.

21, Pao2 53; Spo2 89%.

• Respiratory distress (cyanosis, heart rate, respiratory rate, ABGs)

• Pulmonary embolism and infarction likely (history, vital signs, CXR, ECG, blood-tinged sputum, wheezing, pleural friction rub)

• Bronchospasm, probably secondary to pulmonary embolism or infarction (wheezing)

• Alveolar atelectasis and consolidation (CXR)

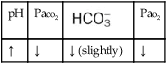

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with moderate hypoxemia (ABGs)

• Pulmonary artery hypertension and low cardiac output probably secondary to pulmonary embolism (clinical presentation and hemodynamic data)

P Contact physician to request transfer to ICU. Increase oxygen therapy per Protocol. Begin Aerosolized Medication Protocol (med. neb. with 2 mL albuterol premix qid). Monitor and reevaluate in 30 minutes (e.g., ABG). Remain on standby with mechanical ventilator available.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

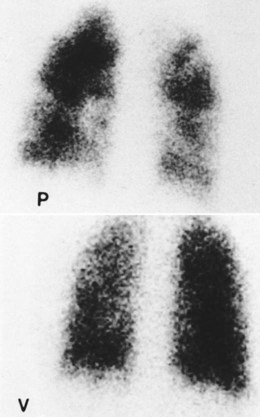

S N/A (patient not responsive)

O Ventilation-perfusion scan: no blood flow to right middle lobe; cyanosis; cough: small amount of blood-tinged sputum; vital signs: BP 70/35, HR 160, RR 25 and shallow, T 37.5° C (99.2° F); palpation negative; dull percussion notes over right middle lobe; wheezing over both lung fields; pleural friction rub over right middle lobe; ECG: alternating among normal sinus rhythm, sinus tachycardia, and atrial flutter; hemodynamic indices: increased CVP, RAP,  , RVSWI, and PVR and decreased PCWP, CO, SV, SVI, and CI; ABGs on 100% O2: pH 7.25, Paco2 69,

, RVSWI, and PVR and decreased PCWP, CO, SV, SVI, and CI; ABGs on 100% O2: pH 7.25, Paco2 69,  27, Pao2 37; Spo2 64%

27, Pao2 37; Spo2 64%

• Pulmonary embolism and infarction (history, vital signs, hemodynamics, CXR, ECG, blood-tinged sputum, wheezing, pleural friction rub)

P Contact physician stat. Discuss acute ventilatory failure and need for intubation and Mechanical Ventilation Protocol. Manually ventilate until physician arrives. Continue Oxygen Therapy Protocol via manual resuscitation at an Fio2 of 1.0. Increase Aerosolized Medication Protocol (changing med. nebs. to IPPB to assist patient’s work of breathing q4h).

Scan)

Scan)

scan is reliable only at the extremes of interpretation (i.e., the test confirms that the lungs are normal or that there is a high probability of a pulmonary embolism). The

scan is reliable only at the extremes of interpretation (i.e., the test confirms that the lungs are normal or that there is a high probability of a pulmonary embolism). The  scan often raises more questions than it answers. This test is slowly being replaced by more sensitive and rapid tests, such as spiral CT scans.

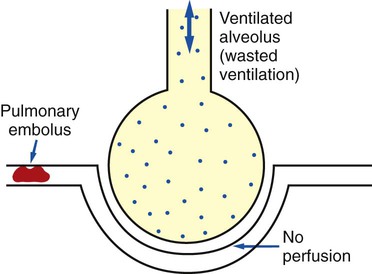

scan often raises more questions than it answers. This test is slowly being replaced by more sensitive and rapid tests, such as spiral CT scans. ) ratio distal to the pulmonary embolus is high and may even be infinite if there is no perfusion at all (

) ratio distal to the pulmonary embolus is high and may even be infinite if there is no perfusion at all (

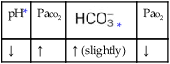

ratio at the onset of a pulmonary embolism, this condition is quickly reversed, and a decrease in the

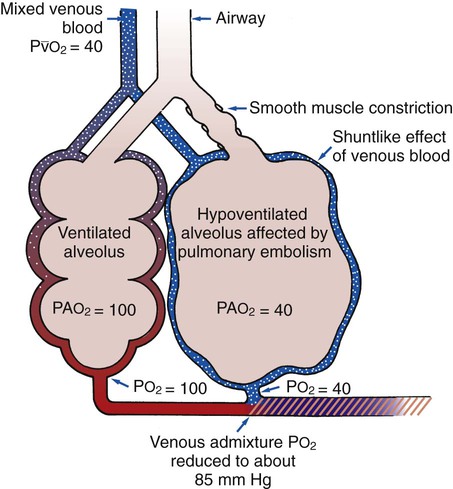

ratio at the onset of a pulmonary embolism, this condition is quickly reversed, and a decrease in the  ratio occurs. The pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the decreased

ratio occurs. The pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for the decreased  ratio are as follows: In response to the pulmonary embolus, pulmonary infarction develops and causes alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, and parenchymal necrosis. In addition, the embolus is believed to activate the release of humoral agents such as serotonin, histamine, and prostaglandins into the pulmonary circulation, causing bronchial constriction. Collectively, the alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, tissue necrosis, and bronchial constriction lead to decreased alveolar ventilation relative to the alveolar perfusion (decreased

ratio are as follows: In response to the pulmonary embolus, pulmonary infarction develops and causes alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, and parenchymal necrosis. In addition, the embolus is believed to activate the release of humoral agents such as serotonin, histamine, and prostaglandins into the pulmonary circulation, causing bronchial constriction. Collectively, the alveolar atelectasis, consolidation, tissue necrosis, and bronchial constriction lead to decreased alveolar ventilation relative to the alveolar perfusion (decreased  ratio). As a result of the decreased

ratio). As a result of the decreased  ratio, pulmonary shunting and venous admixture ensue.

ratio, pulmonary shunting and venous admixture ensue. ratio that develops from the pulmonary infarction (atelectasis and consolidation) and bronchial constriction (release of cellular mediators) that actually causes the reduction of the patient’s arterial oxygen level. As this condition intensifies, the patient’s oxygen level may decline to a point low enough to stimulate the peripheral chemoreceptors, which in turn initiates an increased ventilatory rate.

ratio that develops from the pulmonary infarction (atelectasis and consolidation) and bronchial constriction (release of cellular mediators) that actually causes the reduction of the patient’s arterial oxygen level. As this condition intensifies, the patient’s oxygen level may decline to a point low enough to stimulate the peripheral chemoreceptors, which in turn initiates an increased ventilatory rate.

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

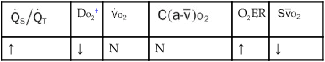

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance. ratio to decrease and the P

ratio to decrease and the P

24, and Pa

24, and Pa ), right ventricular stroke work index (RVSWI), and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), as well as a decreased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), cardiac output (CO), stroke volume (SV), stroke volume index (SVI), and cardiac index (CI). The chest x-ray showed increased density in the right middle lobe consistent with atelectasis and consolidation. On an F

), right ventricular stroke work index (RVSWI), and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), as well as a decreased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), cardiac output (CO), stroke volume (SV), stroke volume index (SVI), and cardiac index (CI). The chest x-ray showed increased density in the right middle lobe consistent with atelectasis and consolidation. On an F 21, and Pa

21, and Pa , RVSWI, and PVR and decreased PCWP, CO, SV, SVI, and CI. The patient’s ABGs on 100% oxygen were as follows: pH 7.25, Pa

, RVSWI, and PVR and decreased PCWP, CO, SV, SVI, and CI. The patient’s ABGs on 100% oxygen were as follows: pH 7.25, Pa 27, and Pa

27, and Pa