Chapter 57

Pulmonary Embolism

1. Who first described pulmonary embolism?

3. What percentage of patients with acute PE have clinical evidence of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT)?

4. What percentage of patients with proximal DVT will develop PE?

Approximately 50% of patients with proximal DVT will develop PE.

5. What is the usual cause of death in subjects with PE?

6. What are the major risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Risk factors are crucial in raising suspicion for acute VTE, although the disease may be idiopathic. Previous thromboembolism, immobility, cancer, advanced age, major surgery, trauma, acute medical illness, and certain thrombophilias impart significant risk. A list of risk factors for VTE is shown in Box 57-1.

7. How commonly are recommended VTE prevention measures used?

8. How should a patient with suspected DVT be initially evaluated?

The symptoms and signs of DVT are nonspecific, and although clinical prediction rules can be useful, there should be a low threshold to proceed to compression ultrasonography. D-dimer testing may be useful; the diagnosis of DVT can be excluded without the need for ultrasound if the patient has a combination of a low or moderate clinical probability estimate and a negative D-dimer result. If the patient falls into the moderate or high clinical pretest probability or has a positive D-dimer test, further evaluation with ultrasound is advised. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based D-dimer tests have superior sensitivity (96% to 98%). DVT is discussed further in Chapter 50.

9. What are the symptoms and signs of acute PE?

Dyspnea (either sudden in onset or evolving over days)

Dyspnea (either sudden in onset or evolving over days)

Chest pain, often pleuritic (such chest pain may be associated with chest wall tenderness and generally occurs with pulmonary infarct)

Chest pain, often pleuritic (such chest pain may be associated with chest wall tenderness and generally occurs with pulmonary infarct)

10. What are four clinical syndromes seen with acute PE?

Massive PE with acute cor pulmonale: Not all patients with acute cor pulmonale will go on to develop hypotension (which defines massive PE), but such a presentation should raise concern.

Massive PE with acute cor pulmonale: Not all patients with acute cor pulmonale will go on to develop hypotension (which defines massive PE), but such a presentation should raise concern.

Submassive PE: This is defined as acute PE which causes RV dysfunction. Of note, based upon the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (see Question 19), low-risk and intermediate-risk categories have been referred to as “nonmassive PE.”

Submassive PE: This is defined as acute PE which causes RV dysfunction. Of note, based upon the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (see Question 19), low-risk and intermediate-risk categories have been referred to as “nonmassive PE.”

Pulmonary infarction and/or pulmonary hemorrhage: Because of dual blood supply and free anastomosis between the pulmonary capillaries, emboli usually don’t cause infarction in a healthy lung. Pulmonary infarction is uncommon when emboli obstruct central arteries but much more common when distal arteries are occluded. Obstruction of distal arteries can result in pulmonary hemorrhage as a result of an influx of bronchial arterial blood at systemic pressure. Hemorrhage causes symptoms and radiographic changes usually attributed to pulmonary infarction.

Pulmonary infarction and/or pulmonary hemorrhage: Because of dual blood supply and free anastomosis between the pulmonary capillaries, emboli usually don’t cause infarction in a healthy lung. Pulmonary infarction is uncommon when emboli obstruct central arteries but much more common when distal arteries are occluded. Obstruction of distal arteries can result in pulmonary hemorrhage as a result of an influx of bronchial arterial blood at systemic pressure. Hemorrhage causes symptoms and radiographic changes usually attributed to pulmonary infarction.

Acute unexplained dyspnea: A diagnosis of PE should be considered in patients with dyspnea of unclear cause and may merit consideration even when there is another potential explanation.

Acute unexplained dyspnea: A diagnosis of PE should be considered in patients with dyspnea of unclear cause and may merit consideration even when there is another potential explanation.

11. What is the Wells score for suspected acute PE?

First described in 1998, the Wells score is a clinical prediction score based on simple, noninvasive clinical parameters. It has evolved over the years, has been validated, and is useful in determining pretest probability for suspected acute PE. Pretest probability can be defined based on the calculated score from the modified Wells score (Table 57-1). PE has ultimately been classified as “unlikely” if the clinical decision score was 4 or less, and “likely” with a score of more than 4 points. This cutoff was chosen because it has been shown to give an acceptable VTE diagnostic failure rate of 1.7% to 2.2% when in combination with a normal D-dimer test result. Moreover, with a score of 4 or less and a negative D-dimer test, no further testing appears to be necessary. A score greater than 4 requires further evaluation, and computed tomographic angiography (CTA) is usually performed. High clinical suspicion, however, should always take precedence, even if the Wells score is low.

TABLE 57-1

THE MODIFIED WELLS PRETEST PROBABILITY SCORING OF PULMONARY EMBOLISM POINT SCORE

∗Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al: Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med 135:98-107, 2001.

12. What are the most common findings on electrocardiography (ECG) in acute PE?

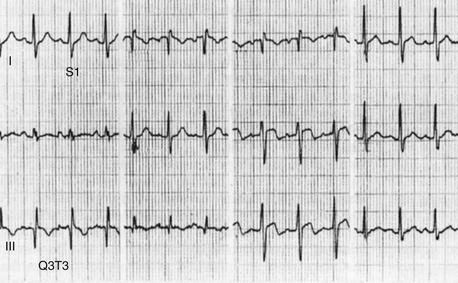

Sinus tachycardia is commonly present in acute PE. The “classic” S1Q3T3 pattern (Fig. 57-1) is seen in a minority of patients. Other ECG findings include the following:

Figure 57-1 An electrocardiogram in a patient with acute pulmonary embolism (PE). Sinus tachycardia, the most common ECG finding in PE, is present. In addition, there is an S1Q3T3 pattern present, with an S wave in lead I and a Q and T wave in lead III. The S1Q3T3 pattern finding is an uncommon finding in PE, but its presence in the appropriate clinical context should raise suspicion for PE.

Arrhythmias (premature atrial and ventricular beats)

Arrhythmias (premature atrial and ventricular beats)

First-degree atrioventricular block

First-degree atrioventricular block

RV strain (right axis deviation)

RV strain (right axis deviation)

Depression, elevation, or inversion of ST segments and T waves

Depression, elevation, or inversion of ST segments and T waves

ST-T changes, when present, are often most marked in the right precordial leads. Although the ECG may be suggestive of PE, it cannot diagnose or rule out acute PE.

13. What are the common chest radiographic findings in patients with acute PE?

14. What are typical arterial blood gas (ABG) findings in patients with PE?

15. When should a ventilation-perfusion ( ) scan be performed?

) scan be performed?

16. Does a negative CTA indicate that PE is not present with certainty?

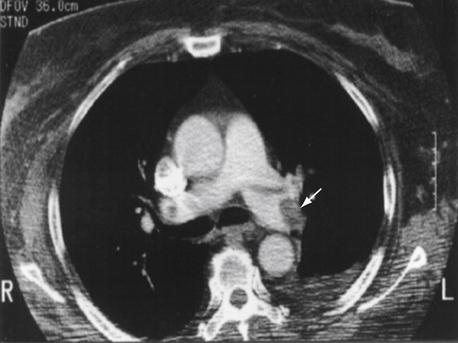

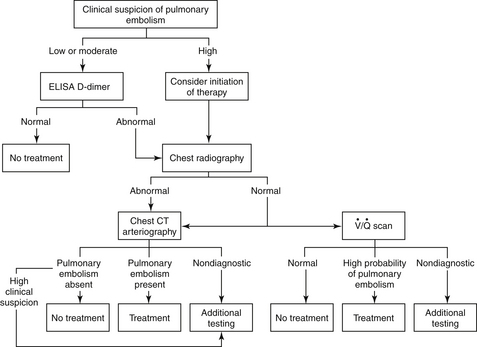

No, but a good quality CTA is extremely sensitive. We learned from the PIOPED II study, published in 2006, that clinical probability is extremely important when considering CTA results. Approximately 60% (9/15) of patients who had high clinical pretest probability but a negative CTA were ultimately diagnosed with PE. Similarly, 42% (16/38) of patients with a low clinical pretest probability and a positive CTA did not have PE. A recent study of more than 3000 patients with suspected acute PE by the Christopher Investigators suggested that if CTA is negative, outcome at 3 months is excellent without therapy. Nonetheless, it is prudent to consider additional imaging when a negative CTA is accompanied by high clinical suspicion; furthermore, imaging quality is not uniformly high in all clinical settings. Finally, computed tomographic (CT) scanning has evolved such that modern day multislice scanners are more sensitive than their predecessors. A large PE, documented by CTA, is shown in Figure 57-2. A diagnostic algorithm, which can be used as a guide, is offered in Figure 57-3.

Figure 57-2 A large embolism (arrow) in the left pulmonary artery is shown by computed tomographic arteriography.

Figure 57-3 A diagnostic strategy for suspected acute pulmonary embolism (PE). The use of a clinical prediction score and D-dimer testing may reduce the need for imaging. If suspicion for acute PE is high and the bleeding risk deemed low, initiation of anticoagulant therapy should be considered. The  scan is most useful when the chest radiograph is normal or minimally abnormal. When significant renal insufficiency is present, computed tomographic arteriography (CTA) is contraindicated and the

scan is most useful when the chest radiograph is normal or minimally abnormal. When significant renal insufficiency is present, computed tomographic arteriography (CTA) is contraindicated and the  scan may be useful. Finally, when chest CTA is nondiagnostic,

scan may be useful. Finally, when chest CTA is nondiagnostic,  scanning can be considered; a negative

scanning can be considered; a negative  scan is highly sensitive and a high-probability scan is quite sensitive. However,

scan is highly sensitive and a high-probability scan is quite sensitive. However,  scans are often nondiagnostic particularly when underlying lung disease is present. When the

scans are often nondiagnostic particularly when underlying lung disease is present. When the  scan is nondiagnostic, and CTA cannot be done, ultrasound of the legs or magnetic resonance imaging of the legs and/or lungs can be considered. A negative leg study, does not, however, rule out PE. (Modified from Tapson VF: Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 358:1037-1052, 2008.) CT, Computed tomography; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay;

scan is nondiagnostic, and CTA cannot be done, ultrasound of the legs or magnetic resonance imaging of the legs and/or lungs can be considered. A negative leg study, does not, however, rule out PE. (Modified from Tapson VF: Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 358:1037-1052, 2008.) CT, Computed tomography; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay;  , ventilation-perfusion.

, ventilation-perfusion.

17. How does echocardiography aid in the diagnosis of PE?

18. What is the most appropriate initial therapy for patients with documented acute PE?

In patients with acute PE, a therapeutic level of anticoagulation should ideally be achieved within 24 hours, because this reduces the risk of recurrence. The 9th American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (ACCP-9) from February 2012, recommend initiation of treatment while awaiting diagnostic tests if clinical suspicion is deemed high. Initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), unfractionated heparin (UFH), or fondaparinux for at least 5 days, together with initiation of oral anticoagulant therapy until the international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 or more for at least 24 hours, is recommended. Warfarin should be started on the first treatment day. ACCP-9 also recommends that in patients with acute nonmassive PE, initial treatment with LMWH rather than intravenous UFH be used, if feasible, based on advantages of LMWH, including subcutaneous rather than intravenous delivery, much less need for monitoring, and a lower rate of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. The LMWH preparations are also more bioavailable and thus, more predictable than standard UFH in terms of degree of anticoagulation. Anticoagulation clearly improves survival in patients with acute symptomatic PE.

19. How should one stratify patient risk with acute PE?

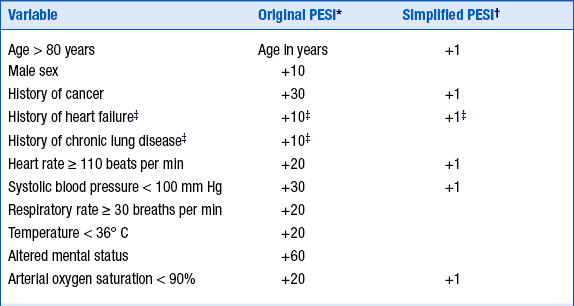

Outcomes of PE depend on a number of factors. The Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) allows stratification on a clinical basis. Several therapeutic implications exist for patients with PE. High-risk patients (who represent about 5% of all symptomatic patients, with about a 15% short-term mortality) should be considered for aggressive treatment with thrombolytic therapy or surgical or catheter embolectomy. Low-risk patients (most patients with PE, with a short-term mortality of about 1%) benefit from anticoagulation therapy, and can sometimes be monitored and followed as outpatients. Intermediate-risk patients (who represent about 30% of all symptomatic patients) should be admitted to the hospital, anticoagulated, and be considered for thrombolytic therapy if indicated. Low-risk and intermediate-risk categories can be referred to as nonmassive PE. The PESI has been simplified (Table 57-2) to ease clinical application. The 305 of 995 patients (30.7%) who were classified as low risk by the simplified PESI had a 30-day mortality of 1.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] of 0.0% to 2.1%) compared with 10.9% (95% CI of 8.5% to 13.2%) in the high-risk group.

TABLE 57-2

ORIGINAL AND SIMPLIFIED PULMONARY EMBOLISM SEVERITY INDEX

∗For the original index, the total point score is reached by adding the total points plus the patient’s age in years: Class 1 = ≤65 points; class 2 = 66-85; class 3 = 86-105; class 4 = 106-125; class 5 = >125. (Classes 1 and 2 are considered low risk, and classes 3-5 high risk.)

†For the simplified index, the total points are added: 0 = low risk, ≥1 = high risk. Empty cells imply that the variable is not included.

‡For the simplified index, history of heart failure and of chronic lung disease are combined as cardiopulmonary disease for 1 point.

20. Are there any laboratory investigations that may help in the prognosis of patients with PE?

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal of B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels and cardiac biomarkers such as troponin T or I may help to identify severity of PE. Elevated troponin has been correlated with increased mortality in acute PE. Neither of these tests, however, is sensitive or specific.

21. What is the primary indication for thrombolytic therapy?

Proven PE with cardiogenic shock is the clearest indication. ACCP-9 also notes that in selected high-risk patients without hypotension who are judged to have a low risk of bleeding, thrombolytic therapy can be considered. This received a grade 2C recommendation—that is, a decision made based on limited data and expert opinion to support the suggestion. An example would be in submassive PE (RV dilation and hypokinesis without hypotension). The decision to use thrombolytic therapy depends on the clinician’s assessment of PE severity, prognosis, and risk of bleeding. Thus, it is often considered in patients with hypotension but without shock. Box 57-2 summarizes recommendations with regard to thrombolytic therapy in PE.

22. What are some complications and contraindications of thrombolytic therapy?

Intracranial hemorrhage is the most devastating complication of thrombolytic therapy and has been reported in approximately 1% of patients in clinical trials, but in about 3% of patients from the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) representing a more “real world” patient population. Other complications include retroperitoneal and gastrointestinal bleeding and bleeding from surgical wounds or from sites of recent invasive procedures. Contraindications to thrombolytic therapy are divided into major and relative contraindications and are listed in Box 57-3.

23. Has thrombolytic therapy been shown to improve mortality from PE?

24. What are the indications for inferior vena caval (IVC) filter placement?

25. What are some complications of IVC filter placement?

IVC filters increase the subsequent incidence of DVT (in about 20% of patients) and have not been shown to increase overall survival. Other complications of IVC filters include procedural-related insertion-site thrombosis (8%), pneumothorax, air embolism, or hematoma, and late complications of IVC thrombosis (2% to 10%), postthrombotic syndrome, IVC penetration, and filter migration. Most models of IVC filters are retrievable, typically within several months of insertion. While this may alleviate some of the late complications of IVC filter placement, complications may also occur with retrieval. Clearly, more data are needed examining the indications for IVC filter placement and the pros and cons of retrieval. At present, the evidence base is inadequate to recommend either retrieval or leaving an IVC filter in place.

26. Can PE be treated as an outpatient?

27. Are there any advances in oral anticoagulation therapy for PE?

Several new oral anticoagulant drugs have been developed. These direct (i.e., antithrombin-independent) inhibitors of factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban) or thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) avoid most of the drawbacks of heparin and could replace vitamin K antagonists and heparins in many patients. These drugs are administered in fixed doses, do not need coagulation monitoring in the laboratory, and have very few drug–drug or drug–food interactions. Dabigatran and rivaroxaban are U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for treatment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Rivaroxaban is also approved for prophylaxis for both total hip and total knee replacement. Both drugs have proven noninferior to warfarin in acute treatment of DVT and PE, after a short period of bridging with LMWH. Oral rivaroxaban was FDA-approved for the treatment of acute DVT and/or PE based upon the EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE studies. In EINSTEIN-PE, oral rivaroxaban was noninferior to the standard approach of parenteral anticoagulation together with warfarin therapy with regard to recurrent VTE events. Importantly, major bleeding rates were significantly less with rivaroxaban.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Christopher Study Investigators. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA. 2006;295:172–179.

2. Chunilal, S.D., Eikelboom, J.W., Attia, J., et al. Does this patient have pulmonary embolism? JAMA. 2003;290:2849–2858.

3. Cohen, A.T., Tapson, V.F., Bergmann, J.F., et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371:387–394.

4. Dalen, J.E. Pulmonary embolism: what have we learned since Virchow? Natural history, pathophysiology, and diagnosis. Chest. 2002;122:1440–1456.

5. Dalen, J.E. Pulmonary embolism: what have we learned since Virchow? Treatment and prevention. Chest. 2002;122:1801–1817.

6. Dong, B., Jirong, Y., Liu, G., Wang, Q., Wu, T. Thrombolytic therapy for pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD004437.

7. Goldhaber, S., Bounameaux, H., et al. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet. 2012;379:1835–1846.

8. Goldhaber, S.Z., Visani, L., De Rosa, M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999;353:1386–1389.

9. Hanna, C.L., Michael, B., Streiff, M.B. The role of vena caval filters in the management of venous thromboembolism. Blood Rev. 2005;19:179–202.

10. Jiménez, D., Aujesky, D., Moores, L., et al. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic PE. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1383–1389.

11. Kearon, C., Akl, E.A., Comerota, A.J., et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e419S–e494S.

12. Kurzyna, M., Torbicki, A., Pruszczyk, P. Disturbed right ventricular ejection pattern as a new Doppler echocardiographic sign of acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:507–511.

13. Piazza, G., Goldhaber, S. Fibrinolysis for acute pulmonary embolism. Vasc Med. 2010;15:419–428.

14. PIOPED Investigators. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1990;263:2753–2759.

15. Simonneau, G., Sors, H., Charbonnier, B., et al. A comparison of low-molecular weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:663–669.

16. Stein, P.D., Alnas, M., Skaf, E., et al. Outcomes and complications of retrievable inferior vena cava filters. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1090–1093.

17. Stein, P.D., Fowler, S.E., Goodman, L.R., et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism (PIOPED II). N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317–2327.

18. Tapson, V.F. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1037–1052.

, ventilation-perfusion.

, ventilation-perfusion.

scan is most useful when the chest radiograph is normal and there is no cardiopulmonary disease. In this setting, it has the highest likelihood of being either normal or high probability. Diagnostic tests (especially those for PE) must be interpreted in light of the patient’s pretest probability score. It is crucial to remember that commonly the

scan is most useful when the chest radiograph is normal and there is no cardiopulmonary disease. In this setting, it has the highest likelihood of being either normal or high probability. Diagnostic tests (especially those for PE) must be interpreted in light of the patient’s pretest probability score. It is crucial to remember that commonly the  scan is low or intermediate probability, even when PE is present.

scan is low or intermediate probability, even when PE is present. scanning may also be useful in patients with abnormal renal function, in which a CTA using iodinated contrast agent may be contraindicated.

scanning may also be useful in patients with abnormal renal function, in which a CTA using iodinated contrast agent may be contraindicated.