Objectives

• Describe the etiology and pathophysiology of selected pulmonary disorders.

• Identify the clinical manifestations of selected pulmonary disorders.

• Explain the treatment of selected pulmonary disorders.

• Discuss the nursing priorities for managing the patient with selected pulmonary disorders.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Understanding the pathology of the disease, the areas of assessment on which to focus, and the usual medical management allows the critical care nurse to more accurately anticipate and plan nursing interventions. This chapter focuses on pulmonary disorders commonly seen in the critical care environment.

Acute Respiratory Failure

Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is a clinical condition in which the pulmonary system fails to maintain adequate gas exchange.1 It is the most common organ failure seen in the intensive care unit today,2,3 with a mortality rate of 22% to 75%.2 Mortality varies directly with the number of additional organ failures.2 Additional risk factors for mortality include history of liver, renal, or hematological dysfunction, presence of shock, and age greater than 55 years.3

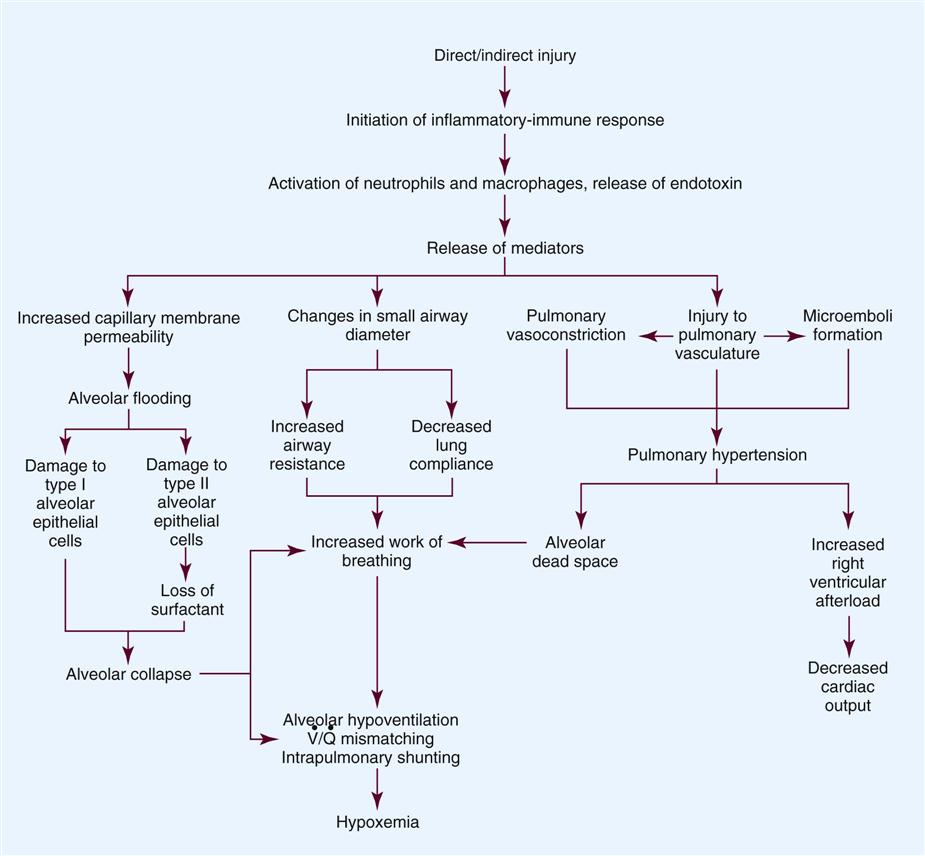

ARF results from a deficiency in the performance of the pulmonary system (Concept Map: Acute Respiratory Failure).1,4 It usually occurs secondary to another disorder that has altered the normal function of the pulmonary system in such a way as to decrease the ventilatory drive, decrease muscle strength, decrease chest wall elasticity, decrease the lung’s capacity for gas exchange, increase airway resistance, or increase metabolic oxygen requirements.5

ARF can be classified as hypoxemic normocapnic respiratory failure (type I) or hypoxemic hypercapnic respiratory failure (type II), depending on analysis of the patient’s arterial blood gases (ABGs). In type I respiratory failure, the patient presents with a low PaO2 and a normal PaCO2, whereas in type II respiratory failure, PaO2 is low and PaCO2 is high.1,4

Etiology

The etiologies of ARF may be classified as extrapulmonary or intrapulmonary, depending on the component of the respiratory system that is affected. Extrapulmonary causes include disorders that affect the brain, the spinal cord, the neuromuscular system, the thorax, the pleura, and the upper airways. Intrapulmonary causes include disorders that affect the lower airways and alveoli, the pulmonary circulation, and the alveolar-capillary membrane.6 Table 15-1 lists the different etiologies of ARF and their associated disorders.

TABLE 15-1

ETIOLOGIES OF ACUTE RESPIRATORY FAILURE

| AFFECTED AREA | DISORDERS* |

| Extrapulmonary | |

| Brain | Drug overdose |

| Central alveolar hypoventilation syndrome | |

| Brain trauma or lesion | |

| Postoperative anesthesia depression | |

| Spinal cord | Guillain-Barré syndrome |

| Poliomyelitis | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | |

| Spinal cord trauma or lesion | |

| Neuromuscular system | Myasthenia gravis |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Neuromuscular-blocking antibiotics | |

| Organophosphate poisoning | |

| Muscular dystrophy | |

| Thorax | Massive obesity |

| Chest trauma | |

| Pleura | Pleural effusion |

| Pneumothorax | |

| Upper airways | Sleep apnea |

| Tracheal obstruction | |

| Epiglottitis | |

| Intrapulmonary | |

| Lower airways and alveoli | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) |

| Asthma | |

| Bronchiolitis | |

| Cystic fibrosis | |

| Pneumonia | |

| Pulmonary circulation | Pulmonary emboli |

| Alveolar-capillary membrane | Acute lung injury (ALI) |

| Inhalation of toxic gases | |

| Near-drowning |

Pathophysiology

Hypoxemia is the result of impaired gas exchange and is the hallmark of acute respiratory failure. Hypercapnia may be present, depending on the underlying cause of the problem. The main causes of hypoxemia are alveolar hypoventilation, ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatching, and intrapulmonary shunting.1,7 Type I respiratory failure usually results from V/Q mismatching and intrapulmonary shunting, whereas type II respiratory failure usually results from alveolar hypoventilation, which may or may not be accompanied by V/Q mismatching and intrapulmonary shunting.1

Alveolar Hypoventilation

Alveolar hypoventilation occurs when the amount of oxygen being brought into the alveoli is insufficient to meet the metabolic needs of the body.6 This can be the result of increasing metabolic oxygen needs or decreasing ventilation.5 Hypoxemia caused by alveolar hypoventilation is associated with hypercapnia and commonly results from extrapulmonary disorders.1,7

Ventilation/Perfusion Mismatching

Ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatching occurs when ventilation and blood flow are mismatched in various regions of the lung in excess of what is normal. Blood passes through alveoli that are underventilated for the given amount of perfusion, leaving these areas with a lower-than-normal amount of oxygen. V/Q mismatching is the most common cause of hypoxemia and is usually the result of alveoli that are partially collapsed or partially filled with fluid.1,7

Intrapulmonary Shunting

The extreme form of V/Q mismatching, intrapulmonary shunting, occurs when blood reaches the arterial system without participating in gas exchange. The mixing of unoxygenated (shunted) blood and oxygenated blood lowers the average level of oxygen present in the blood. Intrapulmonary shunting occurs when blood passes through a portion of a lung that is not ventilated. This may be the result of (1) alveolar collapse secondary to atelectasis or (2) alveolar flooding with pus, blood, or fluid.1,7

If allowed to progress, hypoxemia can result in a deficit of oxygen at the cellular level. As the tissue demands for oxygen continue and the supply diminishes, an oxygen supply/demand imbalance occurs and tissue hypoxia develops. Decreased oxygen to the cells contributes to impaired tissue perfusion and the development of lactic acidosis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.8

Assessment and Diagnosis

The patient with ARF may experience a variety of clinical manifestations, depending on the underlying cause and the extent of tissue hypoxia. The clinical manifestations commonly seen in the patient with ARF are usually related to the development of hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidosis.9 Because the clinical symptoms are so varied, they are not considered reliable in predicting the degree of hypoxemia or hypercapnia1 or the severity of ARF.3

Diagnosing and following the course of respiratory failure is best accomplished by ABG analysis. ABG analysis confirms the level of PaCO2, PaO2, and blood pH. ARF is generally accepted as being present when the PaO2 is less than 60 mm Hg. If the patient is also experiencing hypercapnia, the PaCO2 will be greater than 45 mm Hg. In patients with chronically elevated PaCO2 levels, these criteria must be broadened to include a pH less than 7.35.9

A variety of additional tests are performed depending on the patient’s underlying condition. These include bronchoscopy for airway surveillance or specimen retrieval, chest radiography, thoracic ultrasound, thoracic computed tomography, and selected lung function studies.10

Medical Management

Medical management of the patient with ARF is aimed at treating the underlying cause, promoting adequate gas exchange, correcting acidosis, initiating nutrition support, and preventing complications. Medical interventions to promote gas exchange are aimed at improving oxygenation and ventilation.

Oxygenation

Actions to improve oxygenation include supplemental oxygen administration and the use of positive airway pressure.8 The purpose of oxygen therapy is to correct hypoxemia, and although the absolute level of hypoxemia varies in each patient, most treatment approaches aim to keep the arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation greater than 90%.9 The goal is to keep the tissues’ needs satisfied but not produce hypercapnia or oxygen toxicity.9 Supplemental oxygen administration is effective in treating hypoxemia related to alveolar hypoventilation and V/Q mismatching. When intrapulmonary shunting exists, supplemental oxygen alone is ineffective.11 In this situation, positive pressure is necessary to open collapsed alveoli and facilitate their participation in gas exchange. Positive pressure is delivered via invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation. To avoid intubation, positive pressure is usually administered initially noninvasively via a mask.12,13 For further information on noninvasive ventilation, see Chapter 16.

Ventilation

Interventions to improve ventilation include the use of noninvasive and invasive mechanical ventilation. Depending on the underlying cause and the severity of the ARF, the patient may be initially treated with noninvasive ventilation.12 However, one study found that those patients with a pH of less than 7.25 at initial presentation had an increased likelihood of the need for invasive mechanical ventilation.14 The selection of ventilatory mode and settings depends on the patient’s underlying condition, severity of respiratory failure, and body size. Initially the patient is started on volume ventilation in the assist/control mode. In the patient with chronic hypercapnia, the settings should be adjusted to keep the arterial blood gas values within the parameters expected to be maintained by the patient after extubation.15 For further information on mechanical ventilation see Chapter 16.

Pharmacology

Medications to facilitate dilation of the airways may also be of benefit in the treatment of the patient with ARF. Bronchodilators, such as beta2-agonists and anticholinergic agents, aid in smooth muscle relaxation and are of particular benefit to patients with airflow limitations. Methylxanthines, such as aminophylline, are no longer recommended because of their negative side effects. Steroids also are often administered to decrease airway inflammation and enhance the effects of the beta2-agonists. Mucolytics and expectorants are also no longer used since they have been found to be of no benefit in this patient population.16

Sedation is necessary in many patients to assist with maintaining adequate ventilation. It can be used to comfort the patient and decrease the work of breathing, particularly if the patient is fighting the ventilator. Analgesics should be administered for pain control.17,18 In some patients, sedation does not decrease spontaneous respiratory efforts enough to allow adequate ventilation. Neuromuscular paralysis may be necessary to facilitate optimal ventilation. Paralysis also may be necessary to decrease oxygen consumption in the severely compromised patient.18

Acidosis

Acidosis may occur in the patient for a number of reasons. Hypoxemia causes impaired tissue perfusion, which leads to the production of lactic acid and the development of metabolic acidosis. Impaired ventilation leads to the accumulation of carbon dioxide and the development of respiratory acidosis. Once the patient is adequately oxygenated and ventilated, the acidosis should correct itself. The use of sodium bicarbonate to correct the acidosis has been shown to be of minimal benefit to the patient and thus is no longer recommended as first-line treatment. Bicarbonate therapy shifts the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve to the left and can worsen tissue hypoxia. Sodium bicarbonate may be used if the acidosis is severe (pH <7.1), refractory to therapy, and causing dysrhythmias or hemodynamic instability.19

Nutrition Support

The initiation of nutrition support is of utmost importance in the management of the patient with ARF. The goals of nutrition support are to meet the overall nutritional needs of the patient while avoiding overfeeding, to prevent nutrition delivery-related complications, and to improve patient outcomes.20 Failure to provide the patient with adequate nutrition support results in the development of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and overfeeding can interfere with the performance of the pulmonary system, further perpetuating ARF. Malnutrition decreases the patient’s ventilatory drive and muscle strength, whereas overfeeding increases carbon dioxide production, which then increases the patient’s ventilatory demand, resulting in respiratory muscle fatigue.21

The enteral route is the preferred method of nutrition administration. If the patient cannot tolerate enteral feedings or cannot receive enough nutrients enterally, he or she will be started on parenteral nutrition. Because the parenteral route is associated with a higher rate of complications, the goal is to switch to enteral feedings as soon as the patient can tolerate them.20,21 Nutrition support should be initiated before the third day of mechanical ventilation for the well-nourished patient and within 24 hours for the malnourished patient.20,21

Complications

The patient with acute respiratory failure may experience a number of complications including ischemic-anoxic encephalopathy,22 cardiac dysrhythmias,23 venous thromboembolism,24 and gastrointestinal bleeding.25 Ischemic-anoxic encephalopathy results from hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidosis.22 Dysrhythmias are precipitated by hypoxemia, acidosis, electrolyte imbalances, and the administration of beta2-agonists.23 Maintaining oxygenation, normalizing electrolytes, and monitoring drug levels will facilitate the prevention and treatment of encephalopathy and dysrhythmias.22,23 Venous thromboembolism is precipitated by venous stasis resulting from immobility and can be prevented through the use of graduated compression stockings or pneumatic compression devices and low-dose unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin.24 Gastrointestinal bleeding can be prevented through the use of histamine2-antagonists, cytoprotective agents, or proton pump inhibitors.25 In addition, the patient is at risk for the complications associated with an artificial airway, mechanical ventilation, enteral and parenteral nutrition, and peripheral arterial cannulation.

Nursing Management

Nursing management of the patient with acute respiratory failure incorporates a variety of nursing diagnoses (Nursing Diagnosis Priorities box on Acute Respiratory Failure). Nursing care is directed by the specific etiology of the respiratory failure, although some common interventions are used. Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) optimizing oxygenation and ventilation, (2) providing comfort and emotional support, (3) maintaining surveillance for complications, and (4) educating the patient and family.

Optimizing Oxygenation and Ventilation

Nursing interventions to optimize oxygenation and ventilation include positioning, preventing desaturation, and promoting secretion clearance.

Positioning

Positioning of the patient with ARF depends on the type of lung injury and the underlying cause of hypoxemia. For those patients with V/Q mismatching, positioning is used to facilitate better matching of ventilation with perfusion to optimize gas exchange.26 Because gravity normally facilitates preferential ventilation and perfusion to the dependent areas of the lungs, the best gas exchange would take place in the dependent areas of the lungs.11 Thus the goal of positioning is to place the least affected area of the patient’s lung in the most dependent position. Patients with unilateral lung disease should be positioned with the healthy lung in a dependent position.26,27 Patients with diffuse lung disease may benefit from being positioned with the right lung down, because it is larger and more vascular than the left lung.27,28 For those patients with alveolar hypoventilation, the goal of positioning is to facilitate ventilation. These patients benefit from nonrecumbent positions such as sitting or a semierect position.29 In addition, semirecumbency has been shown to decrease the risk of aspiration and inhibit the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia.30 Frequent repositioning (at least every 2 hours) is beneficial in optimizing the patient’s ventilatory pattern and V/Q matching.31

Preventing Desaturation

A number of activities can prevent desaturation from occurring. These include performing procedures only as needed, hyperoxygenating the patient before suctioning, providing adequate rest and recovery time between various procedures, and minimizing oxygen consumption. Interventions to minimize oxygen consumption include limiting the patient’s physical activity, administering sedation to control anxiety, and providing measures to control fever.29 The patient should be continuously monitored with a pulse oximeter to warn of signs of desaturation.

Promoting Secretion Clearance

Interventions to promote secretion clearance include providing adequate systemic hydration, humidifying supplemental oxygen, coughing, and suctioning. Postural drainage and chest percussion and vibration have been found to be of little benefit in the critically ill patient32,33 and thus are not discussed here.

To facilitate deep breathing, the patient’s thorax should be maintained in alignment and the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees. This position best accommodates diaphragmatic descent and intercostal muscle action.

Once the patient is extubated, deep breathing and incentive spirometry should be started as soon as possible. Deep breathing involves having the patient take a deep breath and holding it for approximately 3 seconds or longer. Incentive spirometry involves having the patient take at least 10 deep, effective breaths per hour using an incentive spirometer. These actions help prevent atelectasis and reexpand any collapsed lung tissue. The chest should be auscultated during inflation to ensure that all dependent parts of the lung are well ventilated and to help the patient understand the depth of breath necessary for optimal effect. Coughing should be avoided unless secretions are present because it promotes collapse of the smaller airways.

Educating the Patient and Family

Early in the patient’s hospital stay, the patient and family should be taught about acute respiratory failure, its etiologies, and its treatment. As the patient moves toward discharge, teaching should focus on the interventions necessary for preventing the reoccurrence of the precipitating disorder (Patient Education box on Acute Respiratory Failure). If the patient smokes, he or she should be encouraged to stop smoking and be referred to a smoking cessation program (Evidence-Based Collaborative Practice box on Smoking Cessation Guidelines). In addition, the importance of participating in a pulmonary rehabilitation program should be stressed. Additional information for the patient can be found at the American Lung Association website (www.lungusa.org).

Collaborative management of the patient with acute respiratory failure is outlined in the Collaborative Management box on Acute Respiratory Failure.

Acute Lung Injury

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a systemic process that is considered to be the pulmonary manifestation of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.34 It is characterized by noncardiac pulmonary edema and disruption of the alveolar-capillary membrane as a result of injury to either the pulmonary vasculature or the airways.35

Many different diagnostic criteria have been used to identify ALI, which has led to confusion, particularly among researchers. In an attempt to standardize the identification of this disorder, the American-European Consensus Committee on ARDS recommended the following criteria be used to diagnose ALI:

• Bilateral infiltrates on chest radiography

• Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP) less than or equal to 18 mm Hg or no clinical evidence of left atrial hypertension36,37

The severest form of ALI is called acute (formerly called “adult”) respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).36 ARDS is identified by the same diagnostic criteria as ALI except that the ratio of PaO2 to FiO2 is less than or equal to 200 mm Hg. As the etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of ALI is the same as for ARDS, the discussion will use the broader term of ALI.37

Etiology

A wide variety of clinical conditions is associated with the development of ALI. These are categorized as direct or indirect, depending on the primary site of injury (Box 15-1).35,38 Direct injuries are those in which the lung epithelium sustains a direct insult. Indirect injuries are those in which the insult occurs elsewhere in the body and mediators are transmitted via the blood stream to the lungs. Sepsis, aspiration of gastric contents, diffuse pneumonia, and trauma were found to be major risk factors for the development of ALI.37

The mortality rate for ARDS is estimated to be 34% to 58%.37

Pathophysiology

The progression of ALI can be described in three phases: exudative, fibroproliferative, and resolution. ALI is initiated with stimulation of the inflammatory-immune system as a result of a direct or indirect injury (Figure 15-1). Inflammatory mediators are released from the site of injury, resulting in the activation and accumulation of the neutrophils, macrophages, and platelets in the pulmonary capillaries. These cellular mediators initiate the release of humoral mediators that cause damage to the alveolar-capillary membrane.38

Exudative Phase

Within the first 72 hours after the initial insult, the exudative phase or acute phase ensues. Once released, the mediators cause injury to the pulmonary capillaries, resulting in increased capillary membrane permeability leading to the leakage of fluid filled with protein, blood cells, fibrin, and activated cellular and humoral mediators into the pulmonary interstitium. Damage to the pulmonary capillaries also causes the development of microthrombi and elevation of pulmonary artery pressures. As fluid enters the pulmonary interstitium, the lymphatics are overwhelmed and unable to drain all the accumulating fluid, resulting in the development of interstitial edema. Fluid is then forced from the interstitial space into the alveoli, resulting in alveolar edema. Pulmonary interstitial edema also causes compression of the alveoli and small airways. Alveolar edema causes swelling of the type I alveolar epithelial cells and flooding of the alveoli. Protein and fibrin in the edema fluid precipitate the formation of hyaline membranes over the alveoli. Eventually, the type II alveolar epithelial cells are also damaged, leading to impaired surfactant production. Injury to the alveolar epithelial cells and the loss of surfactant lead to further alveolar collapse.38,39

Hypoxemia occurs as a result of intrapulmonary shunting and V/Q mismatching secondary to compression, collapse, and flooding of the alveoli and small airways. Increased work of breathing occurs as a result of increased airway resistance, decreased functional residual capacity (FRC), and decreased lung compliance secondary to atelectasis and compression of the small airways. Hypoxemia and the increased work of breathing lead to patient fatigue and the development of alveolar hypoventilation. Pulmonary hypertension occurs as a result of damage to the pulmonary capillaries, microthrombi, and hypoxic vasoconstriction leading to the development of increased alveolar dead space and right ventricular afterload. Hypoxemia worsens as a result of alveolar hypoventilation and increased alveolar dead space. Right ventricular afterload increases and leads to right ventricular dysfunction and a decrease in cardiac output.38

Fibroproliferative Phase

This phase begins as disordered healing and starts in the lungs. Cellular granulation and collagen deposition occur within the alveolar-capillary membrane. The alveoli become enlarged and irregularly shaped (fibrotic) and the pulmonary capillaries become scarred and obliterated. This leads to further stiffening of the lungs, increasing pulmonary hypertension, and continued hypoxemia.38,39

Resolution Phase

Recovery occurs over several weeks as structural and vascular remodeling take place to reestablish the alveolar-capillary membrane. The hyaline membranes are cleared and intraalveolar fluid is transported out of the alveolus into the interstitium. The type II alveolar epithelial cells multiply, some of which differentiate to type I alveolar epithelial cells, facilitating the restoration of the alveolus. Alveolar macrophages remove cellular debris.38,39

Assessment and Diagnosis

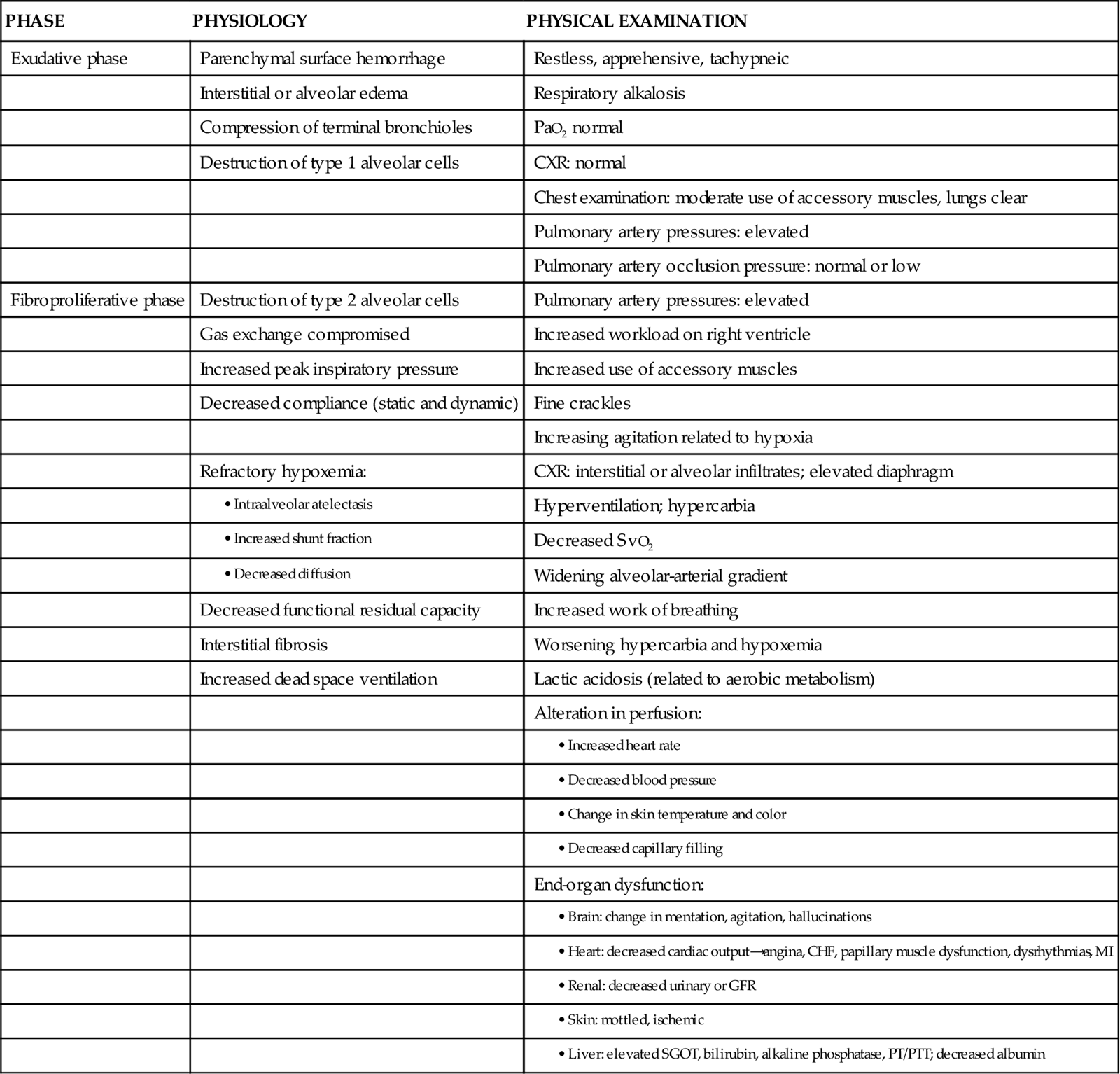

Initially the patient with ALI may be seen with a variety of clinical manifestations, depending on the precipitating event. As the disorder progresses, the patient’s signs and symptoms can be associated with the phase of ALI that he or she is experiencing (Table 15-2). During the exudative phase, the patient presents with tachypnea, restlessness, apprehension, and moderate increase in accessory muscle use. During the fibroproliferative phase, the patient’s signs and symptoms progress to agitation, dyspnea, fatigue, excessive accessory muscle use, and fine crackles as respiratory failure develops.40,41

TABLE 15-2

PHYSIOLOGY AND ASSOCIATED PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF PATIENT WITH ALI

Modified from Phillips JK: Management of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 11(2):233, 1999.

Arterial blood-gas analysis reveals a low PaO2, despite increases in supplemental oxygen administration (refractory hypoxemia).40 Initially the PaCO2 is low as a result of hyperventilation, but eventually the PaCO2 increases as the patient fatigues. The pH is high initially but decreases as respiratory acidosis develops.40,41

Initially the chest x-ray film may be normal, because changes in the lungs do not become evident for up to 24 hours. As the pulmonary edema becomes apparent, diffuse, patchy interstitial and alveolar infiltrates appear. This progresses to multifocal consolidation of the lungs, which appears as a “whiteout” on the chest x-ray film.40

Medical Management

Medical management of the patient with ALI involves a multifaceted approach. This strategy includes treating the underlying cause, promoting gas exchange, supporting tissue oxygenation, and preventing complications. Given the severity of hypoxemia, the patient is intubated and mechanically ventilated to facilitate adequate gas exchange.42

Ventilation

Traditionally the patient with ALI was ventilated with a mode of volume ventilation, such as assist/control ventilation (A/CV) or synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV), with tidal volumes adjusted to deliver 10 to 15 ml/kg. Current research now indicates that this approach may have actually led to further lung injury. It is now known that repeated opening and closing of the alveoli cause injury to the lung units (atelectrauma), resulting in inhibited surfactant production, and increased inflammation (biotrauma), resulting in the release of mediators and an increase in pulmonary capillary membrane permeability. In addition, excessive pressure in the alveoli (barotrauma) or excessive volume in the alveoli (volutrauma) leads to excessive alveolar wall stress and damage to the alveolar-capillary membrane, resulting in air escaping into the surrounding spaces.42 Thus several different approaches have been developed to facilitate the mechanical ventilation of the patient with ALI.

Low Tidal Volume

Low tidal volume ventilation uses smaller tidal volumes (6 ml/kg) to ventilate the patient, in an attempt to limit the effects of barotrauma and volutrauma. The goal is to provide the maximum tidal volume possible while maintaining end-inspiratory plateau pressure less than 30 cm H2O. To allow for adequate carbon dioxide elimination, the respiratory rate is increased to 20 to 30 breaths/min.42,43

Permissive Hypercapnia

Permissive hypercapnia uses low tidal volume ventilation in conjunction with normal respiratory rates, in an attempt to limit the effects of atelectrauma and biotrauma. Normally, to maintain normocapnia the patient’s respiratory rate would have to be increased to compensate for the small tidal volume. In ALI though, increasing the respiratory rate can lead to worsening alveolar damage. Thus the patient’s carbon dioxide level is allowed to rise, and the patient becomes hypercapnic. As a general rule, the patient’s PaCO2 should not rise faster than 10 mm Hg per hour and overall should not exceed 80 to 100 mg Hg. Because of the negative cardiopulmonary effects of severe acidosis, the arterial pH is generally maintained at 7.20 or greater. To maintain the pH, the patient is given intravenous sodium bicarbonate or the respiratory rate and/or tidal volume are increased. Permissive hypercapnia is contraindicated in patients with increased intracranial pressure, pulmonary hypertension, seizures, and cardiac failure.44

Pressure Control Ventilation

In pressure control ventilation (PCV) mode, each breath is delivered or augmented with a preset amount of inspiratory pressure as opposed to tidal volume, which is used in volume ventilation. Thus the actual tidal volume the patient receives varies from breath to breath. PCV is used to limit and control the amount of pressure in the lungs and decrease the incidence of volutrauma. The goal is to keep the patient’s plateau pressure (end-inspiratory static pressure) lower than 30 cm H2O. A known problem with this mode of ventilation is that as the patient’s lungs get stiffer, it becomes harder and harder to maintain an adequate tidal volume and severe hypercapnia can occur.42,43

Inverse Ratio Ventilation

Another alternative ventilatory mode that is used in managing the patient with ALI is inverse ratio ventilation (IRV), either pressure-controlled or volume-controlled. IRV prolongs the inspiratory (I) time and shortens the expiratory (E) time, thus reversing the normal I : E ratio. The goal of IRV is to maintain a more constant mean airway pressure throughout the ventilatory cycle, which helps keep alveoli open and participating in gas exchange. It also increases FRC and decreases the work of breathing. In addition, as the breath is delivered over a longer period of time, the peak inspiratory pressure in the lungs is decreased. A major disadvantage to IRV is the development of auto-positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). As the expiratory phase of ventilation is shortened, air can become trapped in the lower airways, creating unintentional PEEP (also known as auto-PEEP), which can cause hemodynamic compromise and worsening gas exchange. Patients on IRV usually require heavy sedation with neuromuscular blockade to prevent them from fighting the ventilator.42,43

High-Frequency Oscillatory Ventilation

Another alternative ventilatory mode that is used in patients who remain severely hypoxemic despite the treatments previous described is high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV). The goal of this method of ventilation is similar to that of IRV in that it uses a constant airway pressure to promote alveolar recruitment while avoiding overdistention of the alveoli. HFOV uses a piston pump to deliver very low tidal volumes at very high rates or oscillations (300 to 3000 breaths/min).45

Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen is administered at the lowest level possible to support tissue oxygenation. Continued exposure to high levels of oxygen can lead to oxygen toxicity, which perpetuates the entire process. The goal of oxygen therapy is to maintain an arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation of 90% or greater using the lowest level of oxygen—preferably less than 0.50.35

Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP)

Because the hypoxemia that develops with ALI is often refractory or unresponsive to oxygen therapy, it is necessary to facilitate oxygenation with PEEP. The purpose of using PEEP in the patient with ALI is to improve oxygenation while reducing FiO2 to less toxic levels. PEEP has several positive effects on the lungs, including opening collapsed alveoli, stabilizing flooded alveoli, and increasing FRC. Thus PEEP decreases intrapulmonary shunting and increases compliance. PEEP also has several negative effects including (1) decreasing cardiac output (CO) as a result of decreasing venous return secondary to increased intrathoracic pressure and (2) barotrauma, as a result of gas escaping into the surrounding spaces secondary to alveolar rupture. The amount of PEEP a patient requires is determined by evaluating both arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation and cardiac output. In most cases, a PEEP of 10 to 15 cm H2O is adequate. If PEEP is too high, it can result in overdistention of the alveoli, which can impede pulmonary capillary blood flow, decrease surfactant production, and worsen intrapulmonary shunting. If PEEP is too low, it allows the alveoli to collapse during expiration, which can result in more damage to alveoli.42

Tissue Perfusion

Adequate tissue perfusion depends on an adequate supply of oxygen being transported to the tissues. An adequate CO and hemoglobin level is critical to oxygen transport. CO depends on heart rate, preload, afterload, and contractility. A variety of fluids and medications are used to manipulate this parameter. Newer approaches to fluid management include maintaining a very low intravascular volume (pulmonary artery occlusion pressure of 5 to 8 mm Hg) with fluid restriction and diuretics, while supporting the CO with vasoactive and inotropic medications. The goal is to decrease the amount of fluid leakage into the lungs.46

Nursing Management

Nursing management of the patient with ALI incorporates a variety of nursing diagnoses (Nursing Diagnosis Priorities box on Acute Lung Injury). Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) optimizing oxygenation and ventilation, (2) providing comfort and emotional support, and (3) maintaining surveillance for complications.

Optimizing Oxygenation and Ventilation

Nursing interventions to optimize oxygenation and ventilation include positioning, preventing desaturation, and promoting secretion clearance. For further discussion on these interventions, see Nursing Management of Acute Respiratory Failure earlier in this chapter. One additional nursing intervention that can be used to improve the oxygenation and ventilation of the patient with ALI is prone positioning.

Prone Positioning

A number of studies have shown that prone positioning the patient with ALI results in an improvement in oxygenation. Although a number of theories propose how prone positioning improves oxygenation, the discovery that with ALI there is greater damage to the dependent areas of the lungs probably provides the best explanation. It was originally thought that ALI was a diffuse homogenous disease that affected all areas of the lungs equally. It is now known that the dependent lung areas are more heavily damaged than the nondependent lung areas. Turning the patient prone improves perfusion to less damaged parts of lungs and improves V/Q matching and decreases intrapulmonary shunting. Prone positioning appears to be more effective when initiated during the early phases of ALI.47 For more information on prone positioning see Chapter 16.

Collaborative management of the patient with ALI is outlined in the Collaborative Management box on Acute Lung Injury.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an acute inflammation of the lung parenchyma that is caused by an infectious agent that can lead to alveolar consolidation. Pneumonia can be classified as community-acquired (CAP) or hospital-acquired (HAP). Community-acquired pneumonia is acquired outside of the hospital.48 Severe CAP requires admission to the intensive care unit and accounts for about 10% of all patients with pneumonia. The mortality for this patient group is in excess of 50%.49 Hospital-acquired pneumonia is acquired while in the hospital for at least 48 hours.54 Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a subgrouping of HAP that refers to development of pneumonia after the insertion of an artificial airway. VAP represents 80% of all HAP cases.50

Etiology

The spectra of etiological pathogens of pneumonia vary with the type of pneumonia, as do the risk factors for the disease.

Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Pathogens that can cause severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Legionella species, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, respiratory viruses, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.51 A number of factors increase the risk for developing CAP, including alcoholism; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); and comorbid conditions such as diabetes, malignancy, and coronary artery disease.48 Impaired swallowing and altered mental status also contribute to the development of CAP, because they result in an increased exposure to the various pathogens due to chronic aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions.48

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia

Pathogens that can cause hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) include S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Serratia spp., fungi, and respiratory viruses.50 Two of the pathogens most frequently associated with VAP are S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.30 Risk factors for HAP can be categorized as host-related, treatment-related, and infection-control-related (Box 15-2).30

Pathophysiology

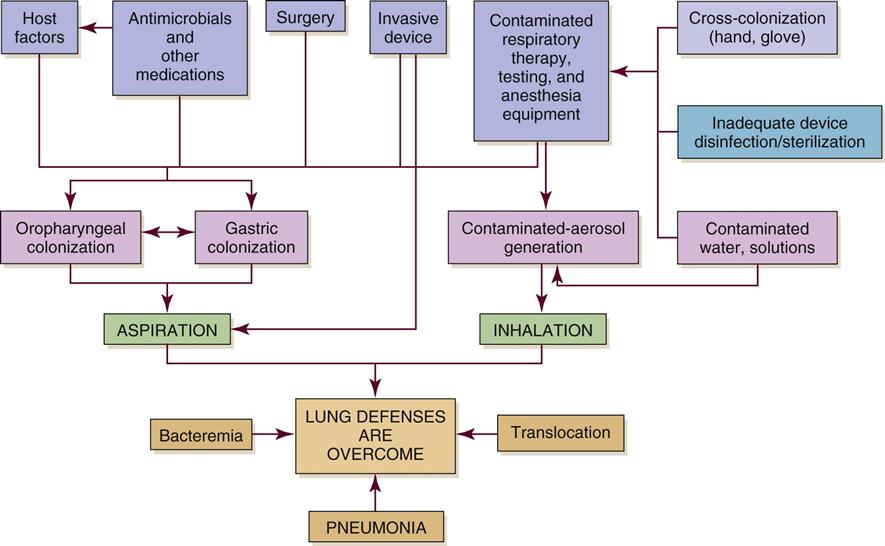

Development of acute pneumonia implies a defect in host defenses, a particularly virulent organism, or an overwhelming inoculation event. Bacterial invasion of the lower respiratory tract can occur by inhalation of aerosolized infectious particles, aspiration of organisms colonizing the oropharynx, migration of organisms from adjacent sites of colonization, direct inoculation of organisms into the lower airway, spread of infection to the lungs from adjacent structures, spread of infection to the lung through the blood, and reactivation of latent infection (usually in the setting of immunosuppression). The most common mechanism appears to be aspiration of oropharyngeal organisms.52 Table 15-3 lists the precipitating conditions that can facilitate the development of pneumonia.

TABLE 15-3

PRECIPITATING CONDITIONS OF PNEUMONIA

| CONDITION | ETIOLOGIES |

| Depressed epiglottal and cough reflexes | Unconsciousness, neurological disease, endotracheal or tracheal tubes, anesthesia, aging |

| Decreased cilia activity | Smoke inhalation, smoking history, oxygen toxicity, hypoventilation, intubation, viral infections, aging, COPD |

| Increased secretion | COPD, viral infections, bronchiectasis, general anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, smoking |

| Atelectasis | Trauma, foreign body obstruction, tumor, splinting, shallow ventilations, general anesthesia |

| Decreased lymphatic flow | Heart failure, tumor |

| Fluid in alveoli | Heart failure, aspiration, trauma |

| Abnormal phagocytosis and humoral activity | Neutropenia, immunocompetent disorders, patients receiving chemotherapy |

| Impaired alveolar macrophages | Hypoxemia, metabolic acidosis, cigarette smoking history, hypoxia, alcohol use, viral infections, aging |

Figure 15-2 depicts the pathophysiology of HAP. Colonization of the patient’s oropharynx with infectious organisms is a major contributor to the development of HAP. Normally the oropharynx has a stable population of resident flora that may be anaerobic or aerobic. When stress occurs, such as with illness, surgery, or infection, pathogenic organisms replace normal resident flora. Previous antibiotic therapy also affects the resident flora population, making replacement by pathological organisms more likely. The pathogens are then able to invade the sterile lower respiratory tract.30

Disruption of the gag and cough reflexes, altered consciousness, abnormal swallowing, and artificial airways all predispose the patient to aspiration and colonization of the lungs and subsequent infection. Histamine2 agonists, antacids, and enteral feedings also contribute to this problem because they raise the pH of the stomach and promote bacterial overgrowth. The nasogastric tube then acts as a wick, facilitating the movement of bacteria from the stomach to the pharynx, where the bacteria can be aspirated.48

Infection results in pulmonary inflammation with or without significant exudates. Increased capillary permeability occurs, leading to increased interstitial and alveolar fluid. V/Q mismatching and intrapulmonary shunting occurs, resulting in hypoxemia as lung consolidation progresses. Untreated pneumonia can result in ARF and initiation of the inflammatory-immune response. In addition, the patient may develop a pleural effusion. This is the result of the vascular response to inflammation, whereby capillary permeability is increased and fluid from the pulmonary capillaries diffuses into the pleural space.48,53

Prevention of VAP is discussed under the mechanical ventilation section of Chapter 16.

Assessment and Diagnosis

The clinical manifestations of pneumonia will vary with the offending pathogen. The patient may first be seen with a variety of signs and symptoms including dyspnea, fever, and cough (productive or nonproductive). Coarse crackles on auscultation and dullness to percussion may also be present.53 Patients with severe CAP may manifest confusion and disorientation, tachypnea, hypoxemia, uremia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypothermia, and hypotension.52

Chest radiography is used to evaluate the patient with suspected pneumonia. The diagnosis is established by the presence of a new pulmonary infiltrate. The radiographic pattern of the infiltrates will vary with the organism.54 A sputum Gram stain and culture are done to facilitate the identification of the infectious pathogen. In 50% of cases, though, a causative agent is not identified.48 A diagnostic bronchoscopy may be needed, particularly if the diagnosis is unclear or current therapy is not working.49 In addition, a complete blood count with differential, chemistry panel, blood cultures, and arterial blood gases is obtained.51

Medical Management

Medical management of the patient with pneumonia should include antibiotic therapy, oxygen therapy for hypoxemia, mechanical ventilation if acute respiratory failure develops, fluid management for hydration, nutritional support, and treatment of associated medical problems and complications. For patients having difficulty mobilizing secretions, a therapeutic bronchoscopy may be necessary.53,54

Antibiotic Therapy

Although bacteria-specific antibiotic therapy is the goal, this may not always be possible because of difficulties in identifying the organism and the seriousness of the patient’s condition. The time involved obtaining cultures should be balanced against the need to begin some treatment based on the patient’s condition. Empiric therapy has become a generally acceptable approach. In this approach, choice of antibiotic treatment is based on the most likely etiological organism while avoiding toxicity, superinfection, and unnecessary cost. If available, Gram stain results should be used to guide choices of antibiotics. Antibiotics should be chosen that offer broad coverage of the usual pathogens in the hospital or community. Failure to respond to such therapy may indicate that the chosen antibiotic regimen does not appropriately cover all of the etiological pathogens or that a new source of infection has developed.50,51

Currently the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and The Joint Commission (TJC) standards for managing patients with CAP require that the first dose of antibiotics be administered within 6 hours of arrival to the hospital. This timeframe is very controversial and has been the subject of much debate. Those in favor of the standard believe that early antibiotic administration leads to improved outcomes while those not in favor of the standard believe it leads to the overuse of antibiotics. More research is needed to clarify the issue.55

Independent Lung Ventilation

In patients with unilateral pneumonia or severely asymmetric pneumonia, this alternative mode of mechanical ventilation may be necessary to facilitate oxygenation. As the alveoli in the affected lung become flooded with pus, the lung becomes less compliant and difficult to ventilate. This results in a shifting of ventilation to the good lung without a concomitant shift in perfusion and thus an increase in V/Q mismatching. Independent lung ventilation (ILV) allows each lung to be ventilated separately, thus controlling the amount of flow, volume, and pressure each lung receives. A double-lumen endotracheal tube is inserted, and each lumen is usually attached to a separate mechanical ventilator. The ventilator settings are then customized to the needs of each lung to facilitate optimal oxygenation and ventilation.56

Nursing Management

Nursing management of the patient with pneumonia incorporates a variety of nursing diagnoses (Nursing Diagnosis Priorities box on Pneumonia). Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) optimizing oxygenation and ventilation, (2) preventing the spread of infection, (3) providing comfort and emotional support, and (4) maintaining surveillance for complications. In addition, the patient’s response to the antibiotic therapy should be monitored for adverse effects.

Optimizing Oxygenation and Ventilation

Nursing interventions to optimize oxygenation and ventilation include positioning, preventing desaturation, and promoting secretion clearance. For further discussion on these interventions, see Nursing Management of Acute Respiratory Failure earlier in this chapter.

Preventing the Spread of Infection

Prevention should be directed at eradicating pathogens from the environment and interrupting the spread of organisms from person to person. Significant progress has been made in removing contaminants from the patient environment through proper disinfection of respiratory equipment and increased use of disposable supplies. Other possible environmental sources of pathogens include suctioning equipment and indwelling lines. These invasive tools must be given proper aseptic care.30

Proper hand hygiene is the single most important measure available to prevent the spread of bacteria from person to person (Evidence-Based Collaborative Practice box on Hand Hygiene Guidelines). In addition, meticulous oral care, including suctioning of the secretions pooling above the cuff of the artificial airway, is critical to decreasing the bacterial colonization of the oropharynx.30

Collaborative management of the patient with pneumonia is outlined in the Collaborative Management box on Pneumonia.

Aspiration Pneumonitis

The presence of abnormal substances in the airways and alveoli as a result of aspiration is misleadingly called aspiration pneumonia. This term is misleading because the aspiration of toxic substances into the lung may or may not involve an infection. Aspiration pneumonitis is a more accurate title, because injury to the lung can result from the chemical, mechanical, and/or bacterial characteristics of the aspirate.

Etiology

A number of factors have been identified that place the patient at risk for aspiration (Table 15-4). Gastric contents and oropharyngeal bacteria (see Pneumonia earlier in this chapter) are the most common aspirates of the critically ill patient.57,58 The effects of gastric contents on the lungs will vary based on the pH of the liquid. If the pH is less than 2.5, the patient will develop a severe chemical pneumonitis resulting in hypoxemia. If the pH is greater than 2.5, the immediate damage to the lungs will be lessened but the elevated pH may have promoted bacterial overgrowth of the stomach.57,58 Once the bacteria-laden gastric contents are aspirated into the lungs, overwhelming bacterial pneumonia can develop.58

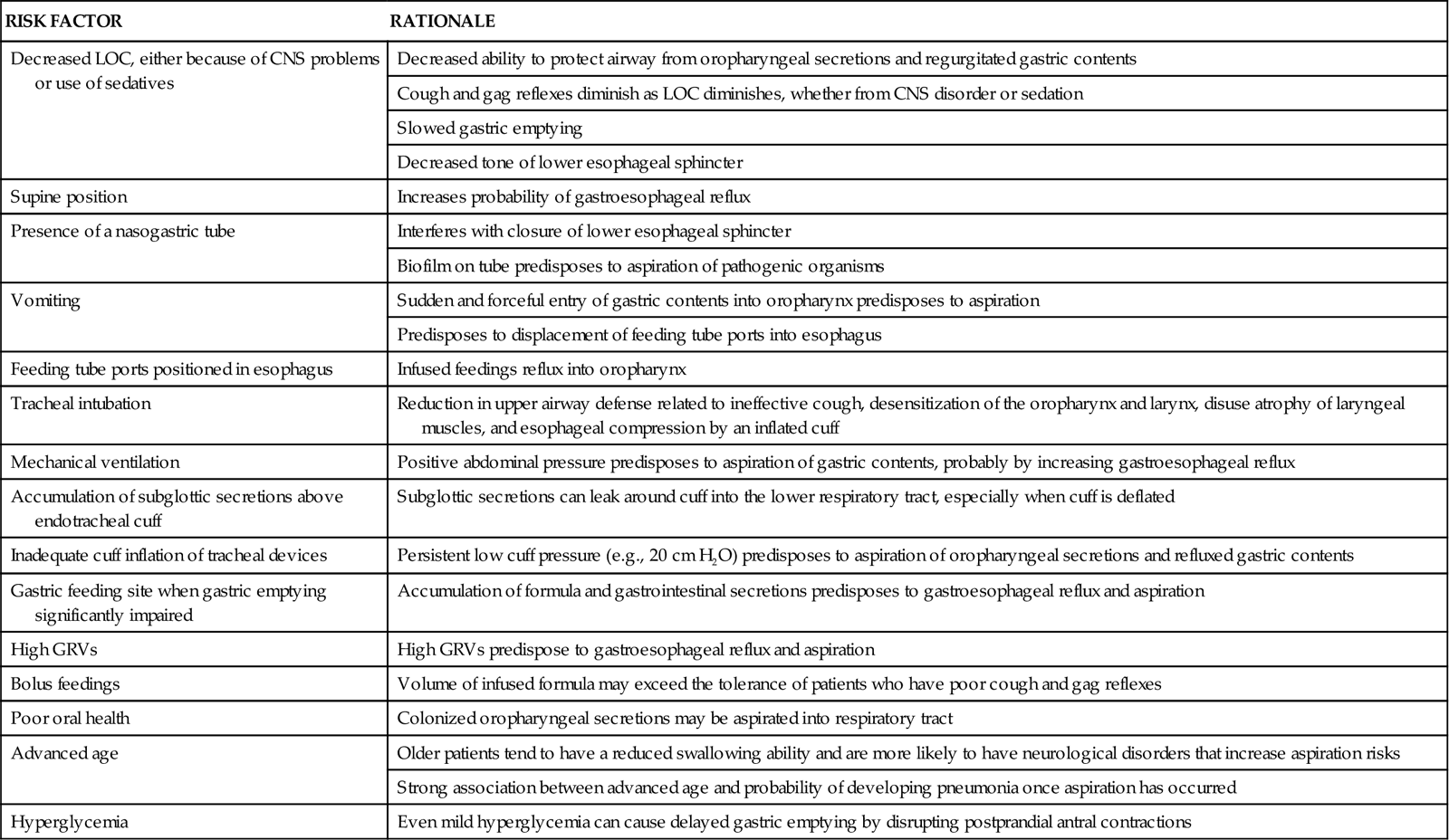

TABLE 15-4

RISK FACTORS FOR ASPIRATION/ASPIRATION-RELATED PNEUMONIA

| RISK FACTOR | RATIONALE |

| Decreased LOC, either because of CNS problems or use of sedatives | Decreased ability to protect airway from oropharyngeal secretions and regurgitated gastric contents |

| Cough and gag reflexes diminish as LOC diminishes, whether from CNS disorder or sedation | |

| Slowed gastric emptying | |

| Decreased tone of lower esophageal sphincter | |

| Supine position | Increases probability of gastroesophageal reflux |

| Presence of a nasogastric tube | Interferes with closure of lower esophageal sphincter |

| Biofilm on tube predisposes to aspiration of pathogenic organisms | |

| Vomiting | Sudden and forceful entry of gastric contents into oropharynx predisposes to aspiration |

| Predisposes to displacement of feeding tube ports into esophagus | |

| Feeding tube ports positioned in esophagus | Infused feedings reflux into oropharynx |

| Tracheal intubation | Reduction in upper airway defense related to ineffective cough, desensitization of the oropharynx and larynx, disuse atrophy of laryngeal muscles, and esophageal compression by an inflated cuff |

| Mechanical ventilation | Positive abdominal pressure predisposes to aspiration of gastric contents, probably by increasing gastroesophageal reflux |

| Accumulation of subglottic secretions above endotracheal cuff | Subglottic secretions can leak around cuff into the lower respiratory tract, especially when cuff is deflated |

| Inadequate cuff inflation of tracheal devices | Persistent low cuff pressure (e.g., 20 cm H2O) predisposes to aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions and refluxed gastric contents |

| Gastric feeding site when gastric emptying significantly impaired | Accumulation of formula and gastrointestinal secretions predisposes to gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration |

| High GRVs | High GRVs predispose to gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration |

| Bolus feedings | Volume of infused formula may exceed the tolerance of patients who have poor cough and gag reflexes |

| Poor oral health | Colonized oropharyngeal secretions may be aspirated into respiratory tract |

| Advanced age | Older patients tend to have a reduced swallowing ability and are more likely to have neurological disorders that increase aspiration risks |

| Strong association between advanced age and probability of developing pneumonia once aspiration has occurred | |

| Hyperglycemia | Even mild hyperglycemia can cause delayed gastric emptying by disrupting postprandial antral contractions |

CNS, central nervous system; GRVs, gastric residual volumes; LOC, level of consciousness.

From Metheny NA: Strategies to prevent aspiration-related pneumonia in tube-fed patients, Respir Care Clin N Am 12(4):603, 2006.

Pathophysiology

The type of lung injury that develops after aspiration is determined by a number of factors, including the quality of the aspirate and the status of the patient’s respiratory defense mechanisms.

Acid Liquid

The aspiration of acid (pH <2.5) liquid gastric contents results in the development of bronchospasm and atelectasis almost immediately. Over the next 4 hours, tracheal damage, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, alveolar-capillary breakdown, interstitial edema, and alveolar congestion and hemorrhage occur.59 Severe hypoxemia develops as a result of intrapulmonary shunting and V/Q mismatching. As the disorder progresses, necrotic debris and fibrin fill the alveoli, hyaline membranes form, and hypoxic vasoconstriction occurs, resulting in elevated pulmonary artery pressures.58,59 The clinical course will follow one of three patterns: (1) rapid improvement in 1 week, (2) initial improvement followed by deterioration and development of ARDS or pneumonia, or (3) rapid death from progressive ARF.59

Acid Food Particles

The aspiration of acid (pH <2.5) nonobstructing food particles can produce the most severe pulmonary reaction because of extensive pulmonary damage.63 Severe hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidosis occur.58,59

Nonacid Liquid

The aspiration of nonacid (pH >2.5) liquid gastric contents is similar to acid liquid aspiration initially, but minimal structural damage occurs.63 Intrapulmonary shunting and V/Q mismatching usually start to reverse within 4 hours, and hypoxemia clears within 24 hours.58,59

Nonacid Food Particles

The aspiration of nonacid (pH >2.5) nonobstructing food particles is similar to acid aspiration initially, with significant edema and hemorrhage occurring within 6 hours. After the initial reaction, the response changes to a foreign-body-type reaction with granuloma formation occurring around the food particles within 1 to 5 days.59 In addition to hypoxemia, hypercapnia and acidosis occur as a result of hypoventilation.57,58

Assessment and Diagnosis

Clinically, the patient presents with signs of acute respiratory distress, and gastric contents may be present in the oropharynx. The patient will have shortness of breath, coughing, wheezing, cyanosis, and signs of hypoxemia. Tachypnea, tachycardia, hypotension, fever, and crackles also are present. Copious amounts of sputum are produced as alveolar edema develops.57,58

ABGs reflect severe hypoxemia. Chest x-ray film changes appear 12 to 24 hours after the initial aspiration, with no one pattern being diagnostic of the event. Infiltrates will appear in a variety of distribution patterns depending on the position of the patient during aspiration and the volume of the aspirate. If bacterial infection becomes established, leukocytosis and positive sputum cultures occur.58

Medical Management

Management of the patient with aspiration lung disorder includes both emergency and follow-up treatment. When aspiration is witnessed, emergency treatment should be instituted to secure the airway and minimize pulmonary damage. The upper airway should be suctioned immediately to remove the gastric contents.57,58 Direct visualization by bronchoscopy is indicated to remove large particulate aspirate61 or to confirm an unwitnessed aspiration event.59 Bronchoalveolar lavage is not recommended because this practice disseminates the aspirate in lungs and increases damage. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended either.59

After airway clearance, attention should be given to supporting oxygenation and hemodynamics. Hypoxemia should be corrected with supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation with PEEP, if necessary.57–59 Hemodynamic changes result from fluid shifts into the lungs that can occur after massive aspirations. Monitoring intravascular volume is essential, and judicious amounts of replacement fluids should be instituted to maintain adequate urinary output and vital signs.59

Initially antibiotic therapy is not indicated. If symptoms fail to resolve within 48 hours, empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated. Corticosteroids have not demonstrated to be of any benefit in the treatment of aspiration pneumonitis and thus are not recommended either.58

Nursing Management

Nursing management of the patient with aspiration lung disorder incorporates a variety of nursing diagnoses (Nursing Diagnosis Priorities box on Aspiration). Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) optimizing oxygenation and ventilation, (2) preventing further aspiration events, (3) providing comfort and emotional support, and (4) maintaining surveillance for complications.

Optimizing Oxygenation and Ventilation

Nursing interventions to optimize oxygenation and ventilation include positioning, preventing desaturation, and promoting secretion clearance. For further discussion on these interventions, see Nursing Management of Acute Respiratory Failure earlier in this chapter.

Preventing Aspiration

One of the most important interventions for preventing aspiration is identifying the patient at risk for aspiration. Actions to prevent aspiration include confirming feeding tube placement, checking for signs and symptoms of feeding intolerance, elevating the head of the bed at least 30 degrees, feeding the patient via a small-bore feeding tube or gastrostomy tube, avoiding the use of a large-bore nasogastric tube, ensuring proper inflation of artificial airway cuffs, and frequent suctioning of the oropharynx of an intubated patient to prevent secretions from pooling above the cuff of the tube. For patients at risk for aspiration or intolerant of gastric feedings, the feeding tube should be placed in the small bowel.60

Collaborative management of the patient with aspiration pneumonitis is outlined in the Collaborative Management box on Aspiration Pneumonitis.

Pulmonary Embolism

Description

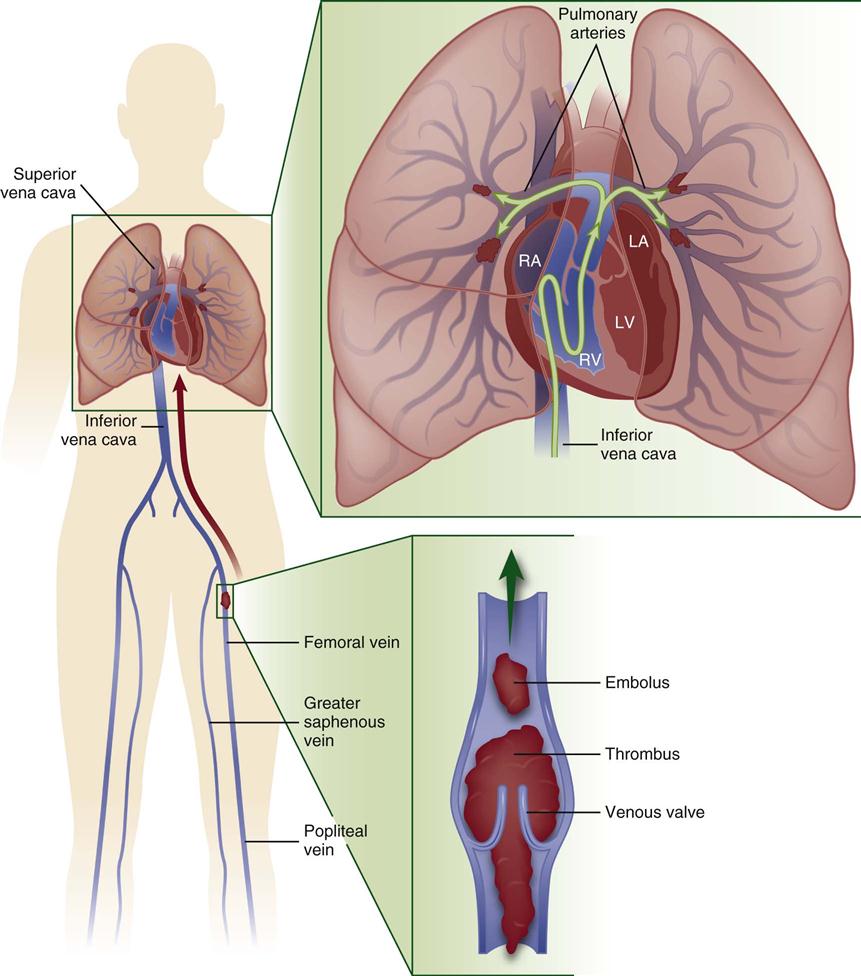

A pulmonary embolism (PE) occurs when a clot (thrombotic embolus) or other matter (nonthrombotic embolus) lodges in the pulmonary arterial system, disrupting the blood flow to a region of the lungs (Figure 15-3). The majority of thrombotic emboli arise from the deep leg veins, particularly the iliac, femoral, and popliteal veins.61 Other sources include the right ventricle, the upper extremities, and the pelvic veins. Nonthrombotic emboli arise from fat, tumors, amniotic fluid, air, and foreign bodies. This section of the chapter focuses on thrombotic emboli.

Pulmonary embolism usually originates from the deep veins of the legs, most commonly the calf veins. These venous thrombi originate predominantly in venous valve pockets and at other sites of presumed venous stasis (inset, bottom). If a clot propagates to the knee vein or above, or if it originates above the knee, the risk of embolism increases. Thromboemboli travel through the right side of the heart to reach the lungs. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. (Modified from Tapson VF: Acute pulmonary embolism, N Engl J Med 358[10]:1037, 2008.)

Etiology

A number of predisposing factors and precipitating conditions put a patient at risk for developing a PE (Box 15-3). Of the three predisposing factors (i.e., hypercoagulability, injury to vascular endothelium, and venous stasis [Virchow’s triad]), endothelial injury appears to be the most significant.61

Pathophysiology

A massive PE occurs with the blockage of a lobar or larger artery, resulting in occlusion of more than 40% of the pulmonary vascular bed. Blockage of the pulmonary arterial system has both pulmonary and hemodynamic consequences.62 The effects on the pulmonary system are increased alveolar dead space, bronchoconstriction, and compensatory shunting.67 The hemodynamic effects include an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular workload.62,63

Increased Dead Space

An increase in alveolar dead space occurs because an area of the lung is receiving ventilation without being perfused. The ventilation to this area is known as wasted ventilation, because it does not participate in gas exchange. This effect leads to alveolar dead space ventilation and an increase in the work of breathing. To limit the amount of dead space ventilation, localized bronchoconstriction occurs.63

Bronchoconstriction

Bronchoconstriction develops as a result of alveolar hypocarbia, hypoxia, and the release of mediators. Alveolar hypocarbia occurs as a consequence of decreased carbon dioxide in the affected area and leads to constriction of the local airways, increased airway resistance, and redistribution of ventilation to perfused areas of the lungs. A variety of mediators are released from the site of the injury, either from the clot or the surrounding lung tissue, which further causes constriction of the airways. Bronchoconstriction promotes the development of atelectasis.63

Compensatory Shunting

Compensatory shunting occurs as a result of the unaffected areas of the lungs having to accommodate the entire cardiac output. This creates a situation in which perfusion exceeds ventilation and blood is returned to the left side of the heart without participating in gas exchange. This leads to the development of hypoxemia.63

Hemodynamic Consequences

The major hemodynamic consequence of a PE is the development of pulmonary hypertension, which is part of the effect of a mechanical obstruction when more than 50% of the vascular bed is occluded. In addition, the mediators released at the injury site and the development of hypoxia cause pulmonary vasoconstriction, which further exacerbates pulmonary hypertension. As the pulmonary vascular resistance increases, so does the workload of the right ventricle as reflected by a rise in PA pressures. Consequently, right ventricular failure occurs, which can lead to decreases in left ventricular preload, CO, and blood pressure, and shock.61–63

Assessment and Diagnosis

The patient with a pulmonary embolism may have any number of presenting signs and symptoms, with the most common being tachycardia and tachypnea. Additional signs and symptoms that may be present include dyspnea, apprehension, increased pulmonic component of the second heart sound (P1), fever, crackles, pleuritic chest pain, cough, evidence of a deep vein thrombosis, and hemoptysis.61 Syncope and hemodynamic instability can occur as a result of right ventricular failure.64

Initial laboratory studies and diagnostic procedures that may be done are ABG analysis, D-dimer, electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiography, and echocardiography (ECHO). ABGs may show a low PaO2, indicating hypoxemia; a low PaCO2, indicating hypocarbia; and a high pH, indicating a respiratory alkalosis. The hypocarbia with resulting respiratory alkalosis is caused by tachypnea.63 An elevated D-dimer will occur with a PE and a number of other disorders. A normal D-dimer will not occur with a PE and thus can be used to rule out a PE as the diagnosis.62 The most frequent ECG finding seen in the patient with a PE is sinus tachycardia.61 The classic ECG pattern associated with a PE—S wave in lead I, and Q wave with inverted T wave in lead III—is seen in fewer than 20% of patients.64 Other ECG findings associated with a PE include right bundle branch block, new-onset atrial fibrillation, T-wave inversion in the anterior or inferior leads65, and ST-segment changes.65 Chest x-ray findings vary from normal to abnormal and are of little value in confirming the presence of a PE. Abnormal findings include cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, elevated hemidiaphragm, enlargement of the right descending pulmonary artery (Palla’s sign), a wedge-shaped density above the diaphragm (Hampton’s hump), and the presence of atelectasis.63 An ECHO, either transthoracic or transesophageal, is also useful in the identification of a PE, because it can provide visualization of any emboli in the central pulmonary arteries. In addition, it can be used for assessing the hemodynamic consequences of the PE on the right side of the heart.62

Differentiating a PE from other illnesses can be difficult because many of its clinical manifestations are found in a variety of other disorders.61 Thus a variety of other tests may be necessary, including a V/Q scintigraphy, pulmonary angiogram, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) studies.61–63 Given the advent of more sophisticated computed tomography (CT) scanners, the spiral CT is also being used to diagnose a PE.63,64 A definitive diagnosis of a PE requires confirmation by a high-probability V/Q scan, an abnormal pulmonary angiogram or CT, or strong clinical suspicion coupled with abnormal findings on lower extremity DVT studies.63

Medical Management

Medical management of the patient with a pulmonary embolism involves both prevention and treatment strategies. Prevention strategies include the use of prophylactic anticoagulation with low-dose or adjusted-dose heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, or oral anticoagulants (Table 15-5). The use of graduated compression stockings and pneumatic compression have also been demonstrated as effective methods of prophylaxis in low-risk patients.65

TABLE 15-5

REGIMENS FOR VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM PROPHYLAXIS

| CONDITION | PROPHYLAXIS |

| General surgery | Unfractionated heparin 5000 units SC TID or |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg SC QD or | |

| Dalteparin 2500 or 5000 units SC QD | |

| Orthopedic surgery | Warfarin (target INR 2.0 to 3.0) or |

| Enoxaparin 30 mg SC BID or | |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg SC QD or | |

| Dalteparin 2500 or 5000 units SC QD or | |

| Fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC QD | |

| Neurosurgery | Unfractionated heparin 5000 units SC BID or |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg SC QD and | |

| Graduated compression stockings/intermittent pneumatic compression | |

| Consider surveillance lower extremity ultrasonography | |

| Oncological surgery | Enoxaparin 40 mg SC QD |

| Thoracic surgery | Unfractionated heparin 5000 units SC TID and |

| Graduated compression stockings/intermittent pneumatic compression | |

| Medical patients | Unfractionated heparin 5000 units SC TID or |

| Enoxaparin 40 mg SC QD or | |

| Dalteparin 5000 units SC QD or | |

| Fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC QD or | |

| Graduated compression stockings/intermittent pneumatic compression for patients with contraindications to anticoagulation | |

| Consider combination pharmacological and mechanical prophylaxis for very high-risk patients | |

| Consider surveillance lower extremity ultrasonography for intensive care unit patients |

SC, subcutaneous; TID, 3 times daily; QD, daily; BID, twice daily.

From Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ: Acute pulmonary embolism: part II: treatment and prophylaxis, Circulation 114(3):e42, 2006.

Treatment strategies include preventing the recurrence of a PE, facilitating clot dissolution, reversing the effects of pulmonary hypertension, promoting gas exchange, and preventing complications. Medical interventions to promote gas exchange include supplemental oxygen administration, intubation, and mechanical ventilation.62

Prevention of Recurrence

Interventions to prevent the recurrence of a PE include the administration of unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin (Coumadin).64 Heparin is administered to prevent further clots from forming and has no effect on the existing clot. The heparin should be adjusted to maintain the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) in the range of 2 to 3 times of upper normal.64 Warfarin should be started at the same time, and when the international normalized ratio (INR) reaches 3.0, the heparin should be discontinued. The INR should be maintained between 2.0 and 3.0. The patient should remain on warfarin for 3 to 12 months depending on his or her risk for thromboembolic disease.64

Interruption of the inferior vena cava is reserved for patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated. The procedure involves placement of a percutaneous venous filter (e.g., Greenfield filter) into the vena cava, usually below the renal arteries. The filter prevents further thrombotic emboli from migrating into the lungs.64

Clot Dissolution

The administration of fibrinolytic agents in the treatment of PE has had limited success. Currently, fibrinolytic therapy is reserved for the patient with a massive PE and concomitant hemodynamic instability. Either recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) or streptokinase may be used. The therapeutic window for using thrombolytic therapy is up to 14 days though the most benefit is usually obtained when given within 48 hours.66

Although often considered as a last resort, a surgical embolectomy may be performed to remove the clot. Generally it is performed as an open procedure while the patient is on cardiopulmonary bypass.69 An emerging alternative to surgical embolectomy is catheter embolectomy. It appears to be particularly useful if surgical embolectomy is not available or is contraindicated. It appears to be most successful when performed within 5 days of the occurrence of the PE.67

Reversal of Pulmonary Hypertension

To reverse the hemodynamic effects of pulmonary hypertension, additional measures may be taken. These include the administration of inotropic agents and fluid. Fluids should be administered to increase right ventricular preload, which would stretch the right ventricle and increase contractility, thus overcoming the elevated pulmonary arterial pressures. Inotropic agents also can be used to increase contractility to facilitate an increase in CO.64

Nursing Management

Prevention of pulmonary embolism should be a major nursing focus, because the majority of critically ill patients are at risk for this disorder. Nursing actions are aimed at preventing the development of DVT, which is a major complication of immobility and a leading cause of PE. These measures include the use of graduated compression stockings or pneumatic compression devices, active/passive range-of-motion exercises involving foot extension, adequate hydration, and progressive ambulation.24

Nursing management of the patient with a PE incorporates a variety of nursing diagnoses (Nursing Diagnosis Priorities box on Pulmonary Embolus). Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) optimizing oxygenation and ventilation, (2) monitoring for bleeding, (3) providing comfort and emotional support, (4) maintaining surveillance for complications, and (5) educating the patient and family.

Optimizing Oxygenation and Ventilation

Nursing interventions to optimize oxygenation and ventilation include positioning, preventing desaturation, and promoting secretion clearance. For further discussion on these interventions, see Nursing Management of Acute Respiratory Failure earlier in this chapter.

Monitoring for Bleeding

The patient receiving anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy should be observed for signs of bleeding. The patient’s gums, skin, urine, stool, and emesis should be screened for signs of overt or covert bleeding. In addition, monitoring the patient’s INR or aPTT is critical to managing the anticoagulation therapy.

Educating the Patient and Family

Early in the patient’s hospital stay, the patient and family should be taught about pulmonary embolus, its etiologies, and its treatment (Patient Education box on Pulmonary Embolus). As the patient moves toward discharge, teaching should focus on the interventions necessary for preventing the reoccurrence of deep vein thrombosis and subsequent emboli, signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis and anticoagulant complications, and measures to prevent bleeding. If the patient smokes, he or she should be encouraged to stop smoking and be referred to a smoking cessation program.

Collaborative management of the patient with a pulmonary embolus is outlined in the Collaborative Management box on Pulmonary Embolus.

Status Asthmaticus

Asthma is a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that is characterized by partially reversible airflow obstruction, airway inflammation, and hyperresponsiveness to a variety of stimuli.68 Status asthmaticus is a severe asthma attack that fails to respond to conventional therapy with bronchodilators, which may result in acute respiratory failure.69

Etiology

The precipitating cause of the attack is usually an upper respiratory infection, allergen exposure, or a decrease in antiinflammatory medications. Other factors that have been implicated include overreliance on bronchodilators, environmental pollutants, lack of access to health care, failure to identify worsening airflow obstruction, and noncompliance with the health care regimen.69

Pathophysiology

An asthma attack is initiated when exposure to an irritant or trigger occurs, resulting in the initiation of the inflammatory-immune response in the airways. Bronchospasm occurs along with increased vascular permeability and increased mucus production. Mucosal edema and thick, tenacious mucus further increase airway responsiveness. The combination of bronchospasm, airway inflammation, and hyperresponsiveness results in narrowing of the airways and airflow obstruction. These changes have significant effects on the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems.69

Pulmonary Effects

As the diameter of the airways decreases, airway resistance increases, resulting in increased residual volume, hyperinflation of the lungs, increased work of breathing, and abnormal distribution of ventilation. V/Q mismatching occurs, which results in hypoxemia. Alveolar dead space also increases as hypoxic vasoconstriction occurs, resulting in hypercapnia.69

Cardiovascular Effects

Inspiratory muscle force also increases in an attempt to ventilate the hyperinflated lungs. This results in a significant increase in negative intrapleural pressure, leading to an increase in venous return and pooling of blood in the right ventricle. The stretched right ventricle causes the intraventricular septum to shift, thereby impinging on the left ventricle. In addition, the left ventricle has to work harder to pump blood from the markedly negative pressure in the thorax to elevated pressure in systemic circulation. This leads to a decrease in cardiac output and a fall in systolic blood pressure on inspiration (pulsus paradoxus).69

Assessment and Diagnosis

Initially the patient may present with a cough, wheezing, and dyspnea. As the attack continues, the patient develops tachypnea, tachycardia, diaphoresis, increased accessory muscle use, and pulsus paradoxus greater than 25 mm Hg. Decreased level of consciousness, inability to speak, significantly diminished or absent breath sounds, and inability to lie supine herald the onset of acute respiratory failure.70–73

Initial ABGs indicate hypocapnia and respiratory alkalosis caused by hyperventilation. As the attack continues and the patient starts to fatigue, hypoxemia and hypercapnia develop.70 Lactic acidosis also may occur as a result of lactate overproduction by the respiratory muscles. The end result is the development of respiratory and metabolic acidosis.71

Deterioration of pulmonary function tests despite aggressive bronchodilator therapy is diagnostic of status asthmaticus and indicates the potential need for intubation. A peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) less than 40% of predicted or an FEV1 (maximum volume of gas that the patient can exhale in 1 second [forced expiratory volume in 1 second]) less than 20% of predicted indicates severe airflow obstruction, and the need for intubation with mechanical ventilation may be imminent.72

Medical Management

Medical management of the patient with status asthmaticus is directed toward supporting oxygenation and ventilation. Bronchodilators, corticosteroids, oxygen therapy, and intubation and mechanical ventilation are the mainstays of therapy.70

Bronchodilators

Inhaled beta2-agonists and anticholinergics are the bronchodilators of choice for status asthmaticus. Beta2-agonists promote bronchodilation and can be administered by nebulizer or metered-dose inhaler (MDI). Usually larger and more frequent doses are given, and the drug is titrated to the patient’s response. Anticholinergics that inhibit bronchoconstriction are not very effective by themselves, but in conjunction with beta2-agonists, they have a synergistic effect and produce a greater improvement in airflow. The routine use of xanthines is not recommended in the treatment of status asthmaticus because they have been shown to have no therapeutic benefit.69–72

A number of studies have focused on the bronchodilator abilities of magnesium. Although it has been demonstrated that magnesium is inferior to beta2-agonists as a bronchodilator, in patients who are refractory to conventional treatment, magnesium may be beneficial. A bolus of 1 to 4 g of intravenous magnesium given over 10 to 40 minutes has been reported to produce desirable effects.69,70,72

A number of other studies are evaluating the effects of leukotriene inhibitors such as zafirlukast, montelukast, and zileuton in the treatment of status asthmaticus. Leukotrienes are inflammatory mediators known to cause bronchoconstriction and airway inflammation. Research suggests that these agents may be beneficial as bronchodilators in those patients who are refractory to beta2-agonists.72

Systemic Corticosteroids

Intravenous or oral corticosteroids also are used in the treatment of status asthmaticus. Their antiinflammatory effects limit mucosal edema, decrease mucus production, and potentiate beta2-agonists. It usually takes 6 to 8 hours for the effects of the corticosteroids to become evident.70 The use of inhaled corticosteroids for the treatment of status asthmaticus remains undecided at this time.69,73 Initial studies indicate they may be beneficial in certain patient populations.73

Oxygen Therapy

Initial treatment of hypoxemia is with supplemental oxygen. High-flow oxygen therapy is administered to keep the patient’s SaO2 greater than 92%.69 Another therapy currently under investigation is the use of heliox. A mixture of helium and oxygen, heliox has a lower density and higher viscosity than an oxygen and air mixture. Heliox is believed to reduce the work of breathing and improve gas exchange because it flows more easily through constricted areas. Studies have shown that it reduces air trapping and carbon dioxide and helps relieve respiratory acidosis.69

Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation

Indications for mechanical ventilation include cardiac or respiratory arrest, disorientation, failure to respond to bronchodilator therapy, and exhaustion.69,71,72 A large endotracheal tube (8 mm) should be used to decrease airway resistance and to facilitate suctioning of secretions. Ventilating the patient with status asthmaticus can be very difficult. High inflation pressures should be avoided because they can result in barotrauma. The use of PEEP should be monitored closely because the patient is prone to developing air trapping. Patient-ventilator asynchrony also can be a major problem. Sedation and neuromuscular paralysis may be necessary to allow for adequate ventilation of the patient.69,71

Nursing Management

Nursing management of the patient with status asthmaticus incorporates a variety of nursing diagnoses (Nursing Diagnosis Priorities box on Status Asthmaticus). Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) optimizing oxygenation and ventilation, (2) providing comfort and emotional support, (3) maintaining surveillance for complications, and (4) educating the patient and family.

Optimizing Oxygenation and Ventilation