CHAPTER 8 Psychological Aspects of Pediatric Anesthesia

Surgery and anesthesia are causes for considerable emotional stress in both parents and children. Because the consequences of this stress occur in the immediate postoperative period and may remain long after the hospital experience has passed, one of the main tasks of the pediatric anesthesiologist is to ensure the psychological, as well as the physiologic, well-being of patients (Chapman et al., 1956; Kain and Mayes, 1996; Kotiniemi et al., 1997a, 1997b; Holm-Knudsen et al., 1998; Aono et al., 1999; Kain et al., 1999a, 1999b, 2006a). To minimize the emotional stress of anesthesia and surgery, the anesthesiologist must understand the psychological developmental milestones of childhood and anticipate situations that a child may find threatening. The latter can often be accomplished with preoperative education, a careful and thoughtful preoperative visit, and the administration of preoperative sedation when other measures are inadequate. During the preoperative visit with the patient, the anesthesiologist can optimally evaluate the levels of anxiety of both the parent(s) and the child, while assessing the child’s medical condition. Of interest is that anesthesiologists are best at predicting which child in the preoperative holding area will be most anxious during induction of anesthesia (MacLaren et al., 2009). In this chapter, the psychological facets of hospitalization and surgery for children and the psychological and medical preparation of pediatric patients for anesthesia and surgery are discussed. A summary of premedications used for children undergoing anesthesia is included.

Psychological preparation for anesthesia and surgery

More than 4 million children undergo surgery in the United States each year, and it is estimated that 50% to 75% of these children experience significant fear and anxiety before their operations (Corman et al., 1958; Vernon et al., 1965; Melamed and Siegel, 1975; Beeby and Hughes, 1980; Kain et al., 1996c). Based on behavioral and physiologic measures of anxiety, induction of anesthesia in children has been identified as the most stressful point during the entire preoperative period (Kain and Mayes, 1996). Appropriate understanding and management of fear and anxiety before surgery are important, because if not managed well, they can lead to both psychological and physiologic adverse outcomes, including postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes and increased postoperative pain and analgesic requirements. As an indicator of the importance of preoperative anxiety, a panel of 72 anesthesiologists ranked various clinical outcomes with low anesthesia morbidity according to importance and frequency (Macario et al., 1999). The three clinical outcomes with the highest combined scores were incisional pain, nausea and vomiting, and preoperative anxiety. Thus, it is important to understand the psychological issues involved when a child undergoes surgery.

Incidence and Definition

Although the exact prevalence of preoperative anxiety in children is difficult to assess because of issues related to measurement and developmental variations, it is estimated that up to 75% of children are reported to exhibit significant psychological or physiologic manifestations of anxiety during the preoperative period (Corman et al., 1958; Vernon et al., 1965; Melamed and Siegel, 1975; Beeby and Hughes, 1980; Kain et al., 1996c). That is, every year up to 3 million children in the United States exhibit significant fear and anxiety before undergoing surgery.

Preoperative anxiety is operationally defined as a subjective feeling of tension, apprehension, nervousness, worry, and vigilance that is associated with increased autonomic nervous system activity (Burton, 1984; Kain and Mayes, 1996). Children are threatened by anticipated parental separation, pain or discomfort, loss of control, uncertainty about “going to sleep,” and masked strangers working in a technical, sterile, non–child-focused environment. Younger children tend to be concerned about separation from parents, and older children are more anxious about the anesthetic and surgical processes. The stress and anxiety experienced by children during induction of anesthesia represent an interaction between child-related factors and environmental conditions in the operating room. Child-related factors include age and developmental maturity, previous experience with medical procedures and illness, individual capacity for affect regulation and trait anxiety, and parental trait anxiety (Lumley et al., 1990, 1993; Kain et al., 1996c; Davidson et al., 2006).

Environmental factors related to the operating room include factors such as interactions with the medical staff, intensity of lights, level of noise produced by the staff and instrument preparation, and the number of medical personnel who interact with the child. Children may appear frightened or agitated, breathe deeply, tremble, stop talking or playing, or start to cry. Other children may become nauseated, wet themselves, have increased motor tone, or attempt to escape from the operating room personnel (Burton, 1984; Kain and Mayes, 1996). These behaviors, which are likely to prolong the induction of anesthesia, give children a sense of control over the situation and therefore diminish the sense of helplessness.

Identification of Children at Risk

Young children, between the ages of 1 and 5 years old, are reported to be at the highest risk for developing significant anxiety before anesthesia and surgery (Brophy and Erickson, 1990; Lumley et al., 1993; Vetter, 1993; Kain et al., 1996a, 1996c). At this age, children are particularly vulnerable because they are young enough to be dependent on their parents, yet old enough to recognize parental absence. Additional factors that enhance the vulnerability of this age group include the degree of inexperience in social contact, ability to communicate and benefit from psychological preparation, and ability to relieve anxiety through play (Hyson, 1983). Although the younger child may not have the cognitive ability to anticipate potential dangers or painful situations during induction of anesthesia, the older child (older than age 6 years) may anticipate pain and fear “going to sleep” (Sparrow et al., 1984). Older children may also rely on a number of coping strategies, including verbal questioning and cognitive mastery (e.g., learning about heart monitors or about what surgeons do) to mediate their anxiety.

Children who have high trait anxiety and who have experienced poor-quality medical encounters in the past are at a particularly high risk to develop high anxiety during the preoperative period (Kain et al., 1996a, 1996c; Davidson et al., 2006). Interestingly, a child who must undergo repeated surgical procedures may respond with either higher-than-expected preoperative anxiety levels or lower-than-expected preoperative anxiety levels. Based on a conditioned learning model, the preoperative situation presents unconditioned fear stimuli that occur repeatedly over short intervals. Thus, children’s previous surgical and medical histories may either exacerbate or attenuate their fear conditioning, and the quality of the previous medical experience (e.g., how distressing it was to the child) is more crucial than its occurrence (Box 8-1).

Several investigations indicate that children who have a shy and inhibited temperament show higher levels of fear and anxiety on the day of surgery compared with other children (Melamed and Ridley-Johnson, 1988; Kain et al., 2001). Conversely, children who have a more socially adaptive temperament are less anxious in the perioperative settings (Kain et al., 2001). Temperament in a child refers to individual patterns of behavior and has been compared with personality traits in adults (Buss et al., 1973; Buss and Plomin, 1975). Kagan et al. (1987) reported that temperament characteristics can be used to predict how a child responds emotionally in a stressful situation; for example, children who are “shy” or “inhibited” tend to become more anxious in novel settings, as suggested by the adrenocortical response and elevated heart rate.

A child’s anxiety before surgery is strongly affected by the state and trait anxiety of the parent (Kain et al., 1996c, 2001). Parental anxiety mediates the child’s response to stressful situations through two pathways (Kain and Mayes, 1996). First, whereas some parents may act as stress reducers for their children, parents who are anxious themselves are typically less available to respond to their children’s needs. Indeed, in these cases the child’s distress may further compound parental anxiety, thus diminishing the parent’s ability to respond effectively. The second pathway of the effect of parental anxiety on a child’s response reflects the genetics of parental disposition and anxiety. Previous research has illustrated that mothers who were more anxious in the surgical setting had children who were also more anxious and that these mothers were less able to respond to their children’s anxiety (Kagan et al., 1987).

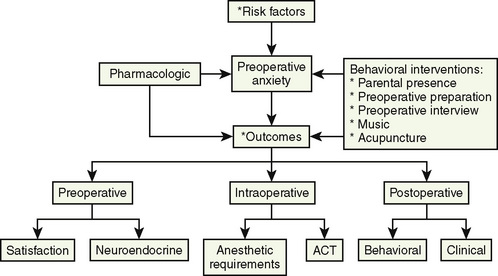

Divorced parents, parents with lower educational levels, and parents of children who were not enrolled in a daycare setting rate themselves as significantly more anxious preoperatively (Kain et al., 1996a, 1996c). Finally, parents of children who are younger than 1 year old, parents who themselves underwent multiple hospitalizations, and parents of children who underwent multiple admissions all report being more anxious (Litman et al., 1996; Shirley et al., 1998). Preoperative anxiety in young children undergoing surgery can be managed with behavioral or pharmacologic (preoperative sedative medication) interventions, or both (Fig. 8-1).

Psychological Preparation Programs

The concept of psychological preparation of children and parents who undergo surgery was introduced almost 50 years ago (Mellish, 1969; Robinson and Kobayashi, 1991). Earlier programs provided the child with information regarding the surgical and anesthetic procedures and sought to develop a rapport between the medical staff and the child (Melamed and Siegel, 1975; Melamed et al., 1976, 1978). In the 1970s, modeling preparation programs were introduced to multiple hospitals in the United States. These modeling programs included the use of illustrated books, video programs, and puppet shows (Melamed and Siegel, 1975; Melamed et al., 1976, 1978). The theory behind these programs was that children would be prepared for the surgical experience by observing other children who underwent similar procedures. During the 1990s, the idea of family-centered care was introduced to medicine in general and to the area of preoperative preparation in particular (Melamed, 1993). Coupled with the development of the child-life discipline and the teaching of coping skills, this concept dominates the preparation programs in current use. Child-life specialists are individuals who facilitate the child’s coping and the perioperative adjustment of children and parents by providing play experiences using modeling techniques (AAP statement, 1993). Child-life specialists incorporate descriptions of the perioperative sensations children experience and provide opportunities to examine, rehearse, and play with perioperative equipment to be used in their care. Child-life specialists also aim to establish supportive relationships with children and parents and to teach relaxation skills, as well as present information to the child and parent about the anesthetic and surgical procedures (AAP statement, 1993).

The regularity with which preparation programs aimed at children undergoing surgery are being used has changed over the past decades. Although these programs were scarce in the 1970s and 1980s, they became quite popular in the 1990s. In fact, in 1996 about 80% of all major acute care children’s hospitals in the United States offered such programs to children and their parents (O’Byrne et al., 1997). Unfortunately, the number of comprehensive preparation programs has been reported as decreasing over the past few years; this new trend is likely the result of new economical constraints in the perioperative environment.

O’Byrne et al. (1997) state that he type of preparation program used varies significantly among different children’s hospitals in the United States. About 89% of children’s hospitals are reported to provide narrative preparation, 87% provide operating-room tours, 86% provide play therapy, and 84% provide printed material. More comprehensive preparation, such as child-life preparation is provided at about 50% of children’s hospitals, and relaxation is taught at about 40% of the hospitals. Interestingly, a panel of experts indicated their consensus regarding the effectiveness of psychological preparation programs before surgery. On a scale of 1 (least effective) to 9 (most effective), child-life preparation was ranked the most effective, followed by play therapy, an operating-room tour, and printed material (O’Byrne et al., 1997).

Although the effectiveness of preparation programs in reduction of anxiety in the holding area is well established, their effectiveness for reducing anxiety during the induction process is questionable (Kain et al., 1996a, 1998a). Methodologic flaws, such as the absence of an appropriate outcome instrument and small sample size, hinder many of the studies that report reduced anxiety in children. In fact, a study that included a validated outcome measure has clearly documented that although a comprehensive psychological preparation program (i.e., child life) is effective in reduction of anxiety in the holding area, it is not effective during the induction of anesthesia or in the recovery room (Kain et al., 1998a). It is likely that the extreme anxiety experienced during induction of anesthesia inhibits children’s abilities to process and implement of the content of the preoperative-preparation program.

Considerations in Choosing a Preparation Program

Timing of the preparation in relation to the day of surgery is a significant factor. That is, children aged 6 years and older benefit most if they participate in the program more than 5 to 7 days before surgery and benefit the least if the program is given 1 day before surgery (Melamed et al., 1976; Robinson and Kobayashi, 1991; Kain et al., 1996a). This extended interval between the preparation and the surgery is needed for older children to have adequate time to process new information provided to them during the preparation process (Melamed et al., 1983; Kain et al., 1996a, 1998a). Typically, older children prepared 1 week ahead of surgery show an immediate increase in the anxiety during the preparation period, with a gradual decrease until the time of surgery (Melamed et al., 1983). Interestingly, there may be a negative effect of a preparation program on younger children. This may be a result of the inability of children younger than age 3 years to separate fantasy from reality (Melamed et al., 1976; Robinson and Kobayashi, 1991). From ages 3 to 6 years, children experience increased ability to separate fantasy from reality, and by the age of 6 years, this distinction of fantasy vs. reality is typically completed (Piaget, 1955).

It is particularly challenging to design a preparation program for children who have been previously hospitalized. Information about what occurs on the day of surgery does not provide new information for these children. Studies have documented that simple modeling and play programs are not beneficial for these children and may actually sensitize these children (Melamed et al., 1983; Faust and Melamed, 1984). Alternative psychological programs, such as teaching extensive, individualized coping skills combined with actual practice, are more helpful for these children (Melamed et al., 1983; Kain et al., 1996a). These alternative programs should be based on the particular experiences the child had during previous surgeries.

Parental Issues

Clearly, preoperative preparation should be directed to parents as well as to children. Multiple studies have reported that parents typically become very anxious when their child undergoes surgery, and parental anxiety was identified as a significant risk factor for increased preoperative anxiety in children (Pinto and Hollandsworth, 1989; Kain et al., 1996a, 1996c; Litman et al., 1996; Shirley et al., 1998; Cassady et al., 1999). Parents experience preoperative anxiety for reasons such as fear of separation and bodily harm to their children, guilt, and financial stress (Cassady et al., 1999). Indeed many parents are more anxious about their children’s health than their own (Kain et al., 1997d). Mothers are more prone to preoperative anxiety than are fathers, particularly when a child is younger than 1 year old or when they are coping with a child’s first surgical experience (Litman et al., 1996; Shirley et al., 1998). Previous research has also documented that women are significantly more concerned with risks and side effects in general, although men specifically articulate a fear of death twice as often as women.

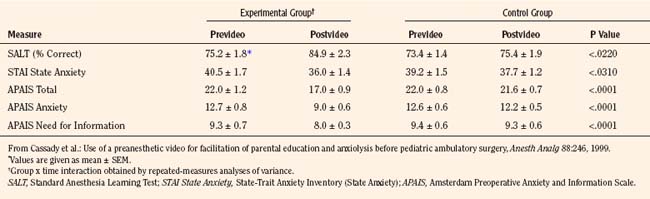

Parents who undergo a preoperative preparation program or who have viewed a preoperative videotape featuring factual information about anesthesia show reduced preoperative anxiety on the day of surgery, but this reduction in anxiety is transient and does not extend to the anesthetic induction, the recovery room, or 2 weeks postoperatively (Table 8-1) (Pinto and Hollandsworth, 1989; Kain et al., 1996a; 1998a; Cassady et al., 1999). Nonetheless, the use of videotapes has received increased attention as a supplementary educational modality for parents, because the tapes are informative, perhaps anxiolytic, and cost effective in certain settings (Pinto and Hollandsworth, 1989; Karl et al., 1990; Cassady et al., 1999; Cassady and Kain, 2000).

Future of Preparation Programs

Most surgeries in the United States are currently conducted on an outpatient basis, and as a result, many children receive preparation for surgery on the morning of the procedure. A major issue with this approach is that because of production pressure, health care providers rarely spend more than a few minutes with the child before surgery (Kain et al., 2009a). As such, a different approach is needed.

Parental Presence

Parental presence during the induction of anesthesia has been suggested as an alternative to sedative premedication. Although there is general agreement about the desirability of parents visiting during their child’s hospitalization, their presence during invasive medical procedures, such as induction of anesthesia, remains very controversial (Lerman, 2000; Kain, 2001). Potential benefits from parental presence include reducing the need for preoperative sedatives and reducing the child’s anxiety and distress on separation to the operating room. Increased child compliance and reduced child anxiety during induction of anesthesia have been suggested to be benefits as well. Common objections to this practice include delays in operating-room schedules, crowded operating rooms, and a possible adverse reaction of the parent during the induction process.

A large-scale, nationwide survey indicated that there is a large variability in hospital policy in the United States toward parental presence in operating rooms. Thirty-two percent of the hospitals allow parental presence; 11% encourage parental presence; 23% have no formal hospital policy; and 26% do not allow it (Kain et al., 2004c).

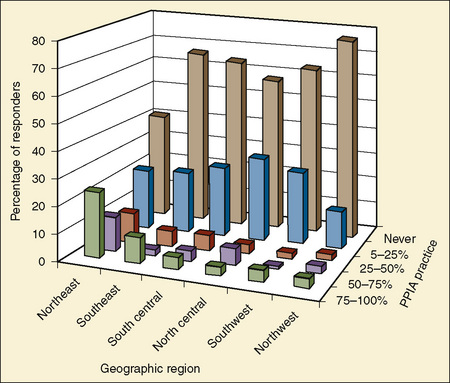

The same survey reported that only 10% of anesthesiologists have parents present during induction of anesthesia in more than 75% of cases, and that 27% of anesthesiologists have parents present during induction in less than 25% of cases. About 50% of all anesthesiologists never have parents present during induction (Kain et al., 2004c). The reported prevalence of parental presence varies widely among the different geographic locations in the United States.

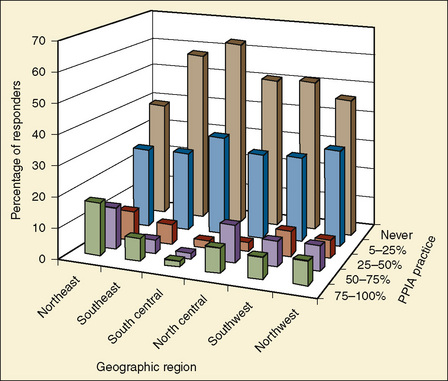

The survey showed that parental presence during induction of anesthesia was practiced most often in the northeast region and least often in the south-central region of the United States (Fig. 8-2). Interestingly, the findings in this survey are very much different from the findings in a nationwide survey conducted in 1995 (Kain et al., 1997c, 2004c) (Fig. 8-3). Overall, there was an increase in the rate of parental presence from 1995 to 2002, and the number of anesthesiologists who never allow parental presence dropped in every geographic region (Kain et al., 1997c, 2004c). These findings may represent a new trend in this practice in the United States.

Parental Perspectives

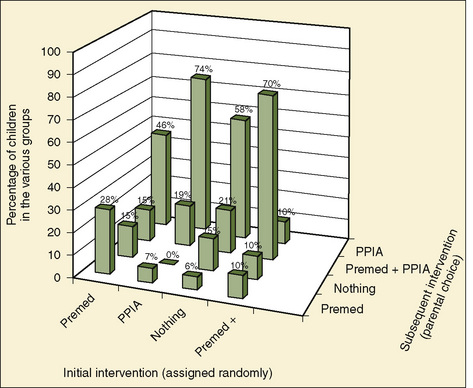

A number of surveys have indicated that most parents prefer to be present during the induction of anesthesia regardless of the child’s age (Braude et al., 1990; Ryder and Spargo, 1991). Furthermore, a majority of parents believe that they are of some help to their child and to the anesthesiologist during the induction process (Ryder and Spargo, 1991). A study indicates that over 80% of parents chose to be present in the operating room when returning for a second operation regardless of whether they were present in the operating room in the first operation (Kain et al., 2003b). This preference for parental presence during induction shown by parents who had experience with other interventions, including preoperative midazolam, is similar to the preference for parental presence shown by parents of children undergoing surgery for the first time (Kain et al., 2003b) (Fig. 8-4). It is no surprise, therefore, that parental presence during the induction of anesthesia is associated with increased parental satisfaction regarding not only the separation process from their child but also with the overall functioning of the hospital (Kain et al., 2000).

Many parents report increased anxiety when they are present during induction of anesthesia (Vessey et al., 1994). An investigation found, however, that anxiety after induction of anesthesia among parents who were present during induction did not differ significantly from anxiety among parents who were not present during the induction process (Kain et al., 2003a). This finding is in agreement with previous randomized controlled trials that have examined this issue (Bevan et al., 1990; Kain et al., 1996b, 1998b, 2000).

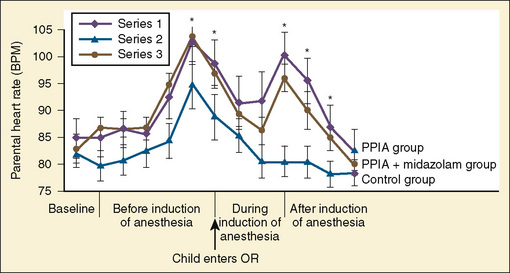

Parental physiologic responses during induction of anesthesia have been examined as well (Kain et al., 2003a). It was found that parental heart rate and skin conductance levels significantly increase as the parents walk to the operating room. Interestingly, once the induction begins, parental heart rate decreases, only to peak again once the parents have to leave the operating room. This second peak in heart rate is in agreement with previous data indicating that the most upsetting factors are seeing the child go limp during induction and then having to leave the child (Vessey et al., 1994). Parental blood pressure after induction of anesthesia was not elevated, and examination of parental data from a Holter monitor revealed no rhythmic abnormalities and no electrocardiographic changes indicative of ischemia (Fig. 8-5) (Kain et al., 2003a).

There have been isolated reports of parental presence resulting in disruptive behavior and even a report of the removal of a child from the operating room by a grandmother (Schofield and White, 1989; Bowie, 1993). In contrast, a 4-year experience with 3086 children in a free-standing ambulatory surgery center found that no parent needed to be escorted from the operating room (Gauderer et al., 1989).

Experimental Studies Involving Parental Presence

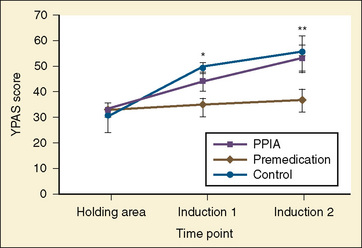

Early studies involving parental presence during induction of anesthesia indicated that the presence of a parent might lower the anxiety of the child (Schulman et al., 1967; Hannallah and Rosales, 1983). These studies, however, were nonrandomized, did not control for confounding variables, and lacked appropriate outcome measurement tools. It is important to note that measurement of a child’s anxiety during induction of anesthesia is a complex issue that necessitates the use of a validated and reliable instrument of a child’s anxiety. Such an instrument, the Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale, was developed and validated a number of years ago (Kain et al., 1995, 1997b). Later studies that used appropriate sample size, eliminated confounding variables, and used appropriate end points and assessment instruments concluded that parental presence does not result in decreased anxiety on the part of the child during the induction process (Hickmott et al., 1989; Bevan et al., 1990; Kain et al., 1996b, 1998b, 2000; Kain, 2001). Further, parental presence during induction of anesthesia was also compared with the use of oral midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) administered 30 minutes before surgery (Kain et al., 1998b). The investigations concluded that the use of oral midazolam is significantly more effective than parental presence in terms of both reducing a child’s anxiety and increasing a child’s compliance (Fig. 8-6) (Kain et al., 1998b).

However, it is clear that research related to the basic concepts underlying parental presence during induction of anesthesia has not changed during the past 2 decades and that the present body of research simply deals with the question of whether parents should be present during induction of anesthesia. Research interests should shift toward an emphasis on what parents actually do during induction of anesthesia rather than simply on their presence. A preliminary publication reports the development of an intervention that consists of an informational and modeling video, instructed graduated exposure and shaping exercises, coached distraction techniques, supportive telephone coaching, and adherence checks (Kain et al., 2002b). This informative modeling intervention is directed at parents of children undergoing surgery and is quite extensive. Results show that children and parents who underwent the extensive parental-preparation program were significantly less anxious than were children whose parents were present during induction of anesthesia and who did not receive the preparation program. More data regarding this preparation program are needed.

Moreover, more recent studies have also attempted to illustrate which children may benefit most from parental presence. In a large-scale prospective cohort study of over 400 children, Kain and colleagues (2006c) demonstrated that children who were older, had lower levels of temperamental activity, and had less anxious parents who valued preparation and coping skills for medical situations benefitted from parental presence at anesthesia induction in terms of anxiety levels and cooperation ratings. In addition, calm parents were found to benefit anxious children during induction of anesthesia, whereas there were no benefits of parental presence when parents were highly anxious (Kain et al., 2006a). In fact, in this large cohort study, calm children who had overly anxious parents present at anesthesia induction were significantly more anxious than calm children who had no parental presence. Finally, it should be noted that the number of parents who are allowed into the operating rooms does not impact the anxiety of the child (Kain et al., 2009b). That is, a child’s anxiety during induction is not higher or lower based on the presence of only one parent as opposed to both parents.

Satisfaction Issues

Previously, the medical community held the view that the only “real” outcomes are those that have an immediate and direct impact on patient morbidity and mortality. This view has changed dramatically, and issues such as patient satisfaction and quality of life are considered by many as equally important as morbidity (Ford et al., 1997). This new development is echoed in review articles in the anesthesia literature suggesting that patient satisfaction should serve as an important end point and indicator of overall quality of anesthesia care (Fung and Cohen, 1998).

A study evaluated parental presence during induction of anesthesia as a contributing factor to their satisfaction. The study also evaluated the effectiveness of parental presence when used in conjunction with oral midazolam (0.5 mg/kg) (Kain et al., 2000). The study has demonstrated that while parental presence did not provide added value in terms of reducing child’s anxiety or increasing a child’s compliance, it did improve parental satisfaction with both the separation process and the entire perioperative process (Kain et al., 2000). Thus, although experimental studies fail to demonstrate the effectiveness of parental presence with regard to anxiety reduction or increased compliance, parental satisfaction seems to improve if the parents are present during the induction of anesthesia.

Medicolegal Issues

The practicing anesthesiologist should also be aware of legal issues associated with parental presence during induction of anesthesia—that is, the additional risks the anesthesiologist incurs because of the presence of a parent in the operating room. The legal literature is not clear with this issue. Of note, however, is a decision made by the Illinois Supreme Court with regard to parental presence during an invasive procedure. In its verdict, the Illinois Supreme Court stated that a hospital that allows a nonpatient to accompany a patient during treatment does not have a duty to protect the nonpatient from fainting (Lewyn, 1993). If medical personnel invite the nonpatient to be present during the treatment, however, the hospital has a legal responsibility toward the nonpatient. Thus, there is an important distinction between allowing parental presence and inviting parental presence. As a response to such possible litigation, a number of hospitals require parents to sign a separate consent form when they express the wish to be present during induction of anesthesia. In a nationwide survey, Kain et al. (2004c) reported that only 5% of all hospitals in the United States indicate that they routinely obtain a separate written consent for parental presence during induction of anesthesia.

Behavioral Interventions

Family-Centered Preparation

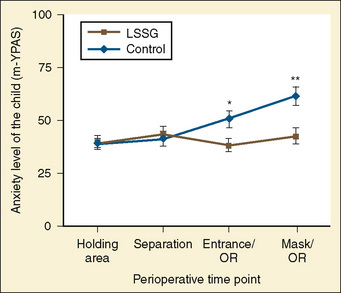

In the contexts of increased attention to family-centered care in the past decade and of the relationship between a parent and a child’s anxiety, Kain and colleagues recently developed a multicomponent, behavioral preoperative-preparation program targeting the family as a whole, rather than the individual child (Kain et al., 2007). Termed ADVANCE (Anxiety-reduction, Distraction, Video modeling and education, Adding parents, No excessive reassurance, Coaching, and Exposure/shaping), this program consists of psychological techniques of shaping, exposure, and modeling with coaching in combination with empirically supported distraction techniques. A randomized controlled trial comparing ADVANCE with standard of care (no premedication or parental presence), standard of care plus parental presence at induction of anesthesia, or standard of care plus midazolam indicated that parents and children in the ADVANCE group exhibited significantly lower levels of preoperative anxiety in the holding area compared with all other groups and lower anxiety during anesthesia induction when compared with the standard-of-care and parental-presence groups (Kain et al., 2007). Moreover, children in the ADVANCE groups had a lower incidence of emergence delirium, required fewer analgesics in recovery, and had a shorter length of stay in recovery as compared with children in the other three groups.

Music

Music has well-established psychological effects, including the induction and modification of moods and emotions (Baeck, 2002; Kain et al., 2002a; Lipe, 2002). Kane, in 1914, is reported to have been one of the first individuals to provide intraoperative music to distract patients from “the horror of surgery.” It was not until about 1960, however, that a group of dentists reported that 65% to 90% of their patients needed little or no anesthesia for dental extractions with the routine use of music during dental surgery (Gardner and Licklider, 1959; Gardner et al., 1960). Music has gained popularity as a part of complementary medicine directed at patients undergoing medical and surgical procedures (Wang et al., 2002a, 2002b, 2003).

The role of music as a therapeutic modality for the treatment of preoperative anxiety in adult patients has been evaluated in several studies. Although a number of studies conducted in this area were hindered by multiple methodologic flaws, the anxiolytic effects of perioperative music are well documented in adults (Standley, 1986; Thompson and Kam, 1995; Miluck-Kolasa et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2002a). As indicated earlier, the anxiety experienced by a child during the induction period is related to personality factors, as well as to operating room factors such as bright lights and high noise levels. Several studies that have assessed noise levels in the operating room concluded that while overall sound levels are not excessive, loud intermittent noises up to 108 dB are present intermittently (Hodge and Thompson, 1990; Nott and West, 2003). Cohen (1970) classified noises as just audible (10 dB), very quiet (50 dB, comparable with light traffic at 30 miles/hr), moderately loud (70 dB, comparable with a dishwasher), very loud (90 dB, comparable with a food blender), and uncomfortably loud (130 dB, comparable with a rock-and-roll band). Interestingly, a sudden noise with a level as little as 30 dB above the background noise (e.g., an SpO2 alarm) might cause an immediate startle response, which is associated with an activation of the sympathetic system, and an anxiolytic response (Falk and Woods, 1973). A study introduced an intervention that consisted of dimmed operating room lights (200 lux) and soft background music (Bach’s “Air on a G String” at 50 to 60 dB), and only the attending anesthesiologist was allowed to interact with the child during induction (Fig. 8-7) (Kain et al., 2002b).The number of medical personnel interacting with the child is of particular importance, as it is not uncommon that the surgeon, the circulating nurse, the anesthesia resident, and the anesthesiologist attending all try to help the child through the induction process. This may result in conflicting messages and increased anxiety on the part of the child. This study found that this combination of music, dim light, and only the attending anesthesiologist interacting with the child was effective and that the children who received this intervention exhibited significantly less anxiety during induction of anesthesia (Kain et al., 2002b).

To date, most reported studies of music therapy in the medical literature describe interventions that consist of patients passively listening to music. Studies that examined live-participation music therapy with children undergoing surgery concluded that this type of music therapy resulted in reduced anxiety in children undergoing surgery (Chetta, 1981; Robb et al., 1995). These studies, however, were limited because of a small sample size and a lack of reliable and valid outcome measures. A more recent trial that used an appropriate sample size and a reliable instrument for measuring outcome indicated some complexities related to this issue (Kain et al., 2004b). The study found that both at separation from parents and on entrance to the operating room, only children who received music therapy from one of the therapists involved in thez study were significantly less anxious than the control group. This anxiolytic effect was present only in the holding area and at separation but not during induction of anesthesia. Thus, it can be concluded that the provision of live-participation music therapy is quite expensive, and considering the results of the more recent study, it is doubtful as to whether this modality should be routinely used to reduce preoperative anxiety in all children undergoing surgery.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture originated in China between the years 2000 and 100 bce (Hsu, 1996). Despite the slow progression of scientific evidence, acupuncture and related techniques have become very popular in the western medical culture over the last few decades.

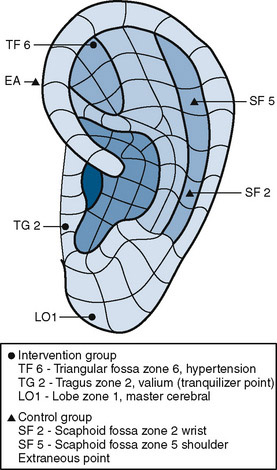

Several studies have examined whether acupuncture is an effective treatment modality for preoperative anxiety. Wang and Kain (2001a, 2001b) found that both healthy volunteers and adult patients undergoing routine outpatient surgery report lower levels of state anxiety after auricular acupuncture provided in specific points. This effect started as early as 30 minutes after insertion of the acupuncture needles. The use of acupuncture as a treatment for parental anxiety was examined as well. Wang and Kain randomized mothers of children who were scheduled for surgery to an acupuncture intervention group or a sham acupuncture control group (Fig. 8-8). The intervention was performed at least 30 minutes before the child’s induction of anesthesia and all mothers were present during induction of anesthesia (Wang et al., 2004).

FIGURE 8-8 Auricular acupuncture points that are used to treat parental anxiety.

(From Wang S, Maranets I, Weinberg M, et al.: Parental auricular acupuncture as an adjunct for parental presence during induction of anesthesia, Anesthesiology 100(6):1399–1404, 2004.)

The investigators found that after induction, maternal anxiety in the acupuncture group was significantly lower, and children whose mothers received the acupuncture intervention were significantly less anxious on entrance to the operating room (Wang et al., 2004). Thus, auricular acupuncture may have various uses in the pediatric perioperative environment. In addition to acupuncture, Wang and colleagues (2005) have also examined parental acupressure as an intervention for preoperative anxiety and found that acupressure at the Yintang point significantly reduced parental self-reported anxiety in the preoperative holding area.

Preoperative Interview

Anesthesiologists undoubtedly have the ability to increase or decrease the anxiety levels of patients; therefore, one should consider the preoperative interview as a psychological intervention that is administered routinely to parents and children (Egbert et al., 1963; Kain et al., 2002a). The anxiety-moderating effect of anesthesiologists is dependent on multiple variables, such as environmental stimuli and the coping style of the parent. That is, patients undergoing surgery generally ask for all relevant information to be provided to them, although some patients and parents have a coping style that is information-seeking, whereas others have a coping style that is information-avoiding (Miller, 1995; Kain et al., 1997a, 1997d). The challenge for the anesthesiologist is to identify the individual coping style of a parent without the benefit of using structured psychological instruments during the preoperative visit.

The impact of information given in the preoperative setting on the anxiety of patients was examined by Miller and Mangan (1983). They found that adult patients who were given extensive information preoperatively were more anxious and uncomfortable. In contrast, no increase in preoperative anxiety was demonstrated in a study that involved English and Scottish men undergoing elective herniorrhaphy who were presented with detailed risk information (Kerrigan et al., 1993). Similarly, a study that involved parents of children undergoing surgery found that the provision of detailed anesthetic information in the setting of a randomized controlled trial did not increase the anxiety of the parents (Kain et al., 1997d). In terms of information desired by children, Fortier and colleagues (2009) recently demonstrated that the majority of children report a strong desire for comprehensive preoperative information, particularly information about pain; however, the impact of providing such information on perioperative outcomes, including anxiety, is not known. Thus, the practicing anesthesiologist should be aware of these data and provide information in the perioperative settings as dictated by the settings and the needs of the parents and the children.

Behavioral outcomes of preoperative anxiety in children

Postoperative Behavioral Changes

Epidemiology

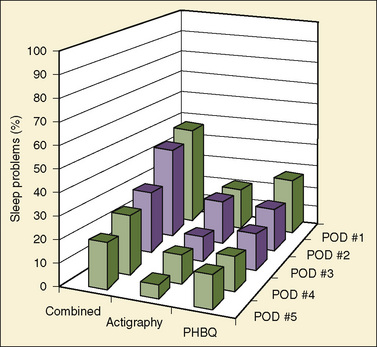

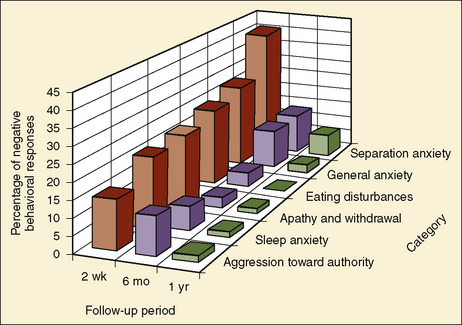

In 1945, Levy described 25 cases of children who developed significant fear of physicians after tonsillectomy. Vernon et al. (1966) developed a structured parental instrument (Posthospitalization Behavior Questionnaire [PHBQ]) that addressed the issue of postoperative behavioral changes in children. Earlier studies that used the PHBQ reported that up to 88% of all children undergoing anesthesia and surgery develop new behavioral changes postoperatively (Vernon et al., 1966; Peterson and Shigetomi, 1982; Thompson and Vernon, 1993). More recent studies conducted in the United States and Europe documented that up to 54% of young children undergoing outpatient surgery experience general anxiety, nighttime crying, enuresis, separation anxiety, and temper tantrums 2 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 8-9) (Kain et al., 1996c; Kotiniemi et al., 1996, 1997a; Kain, 2000). Nearly one-fifth of children continue to demonstrate maladaptive behavior changes 6 months postoperatively, and in 6% of children these behaviors persist at 1 year (Kain et al., 1996c).

FIGURE 8-9 The incidence of postoperative behavioral changes as a function of time after surgery.

(From Kain ZN, Mayes LC, O’Connor T, et al.: Preoperative anxiety in children: predictors and outcomes, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 150:1238–1245, 1996c.)

Nightmares and waking up crying are particularly common problems after surgery in children, and the incidence of these behaviors is as high as 20% 2 weeks postoperatively (Kain et al., 1996c). The effect of outpatient surgery on postoperative sleep patterns was also addressed in a study that used actigraphy, which is an objective measure that aims to quantify sleep (Kain et al., 2002c). The study found that 47% of all children developed postoperative sleeping problems as assessed by either actigraphy or the PHBQ (Kain et al., 2002c). Fourteen percent of children experienced a decrease of at least 1 standard deviation in percentage sleep as assessed by actigraphy (Fig. 8-10) (Kain et al., 2002d).

Considering the dramatic changes that have occurred with health care delivery, this relatively high incidence of postoperative behavioral changes is surprising (Kain, 2000). That is, considering that these were studies that were conducted with outpatients, a lower incidence would be expected. It is important to appreciate, however, that because of economic issues, outpatient surgery for children is being performed with high levels of medical acuity. Children with similar issues underwent inpatient surgery just a few years ago; it may be that efforts to improve the psychological climate of hospitals have been neutralized by other variables.

Predictors

Several studies report that young age is a significant risk factor for the development of postoperative behavioral changes. In 1945, Levy noted a marked reduction in the emotional reaction after surgery in children older than age of 3 years, when the incidence of the new-onset behaviors dropped from 50% to 10%. More recent investigations confirm this observation and report that these postoperative behavioral changes are most common between the ages of 1 and 4 years (Vernon et al., 1965; Kain et al., 1996c). At these ages, children are particularly vulnerable because of issues such as separation anxiety, social inexperience, limited ability to communicate and benefit from psychological preparation, and limited ability to relieve anxiety through play (Kain, 2000).

Increased anxiety of the child and of the parent in the holding area and during induction of anesthesia are both good predictors for later emergence of maladaptive postoperative behaviors (Eckenhoff, 1958; Kain et al., 1996c, 1999a, 2004a, 2006a; Lumley et al., 1993). Meyers and Muravchick (1977) compared postoperative behavioral responses in a group of children who underwent a “steal induction” with a group of children who underwent an “awake” induction. One month after the children were discharged from the hospital, the investigators reported that the rate of behavioral changes was 88% in the awake group and 58% in the steal group. Kain et al. (1999a) confirmed these previous findings and observed that extreme anxiety during induction of anesthesia and forcing the child to the table is associated with a significantly increased occurrence of negative postoperative behavioral changes. Several reports indicate that these behavioral changes are significantly more common among children undergoing tonsillectomy and genitourinary surgery (Manley, 1982; Kain et al., 1996c). Finally, positive behavioral changes have also been reported after surgery, particularly in children with chronic conditions (e.g., recurrent otitis media) that have been improved by the surgery (Kain et al., 1996c; Kotiniemi et al., 1996).

The issue of anesthetic techniques (intravenous vs. mask) has not been demonstrated to be a significant predictor of the incidence of postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes (Kotiniemi and Ryhanen, 1996). In addition, the type of anesthetic used (sevoflurane vs. halothane) has not been shown to predict the incidence of postoperative negative behavioral changes (Kain et al., 2005). Although a history of previous surgery predicted increased incidence of postoperative maladaptive behavior in one study, other studies did not confirm this finding (Lumley et al., 1993; Kain et al., 1996c; Kotiniemi et al., 1997b). It is likely that the quality of surgical experiences is an important predictor, not simply the history of surgery. Quality of past medical experience as a predictor of future anxiety of the child has been reported in studies exploring the issue of preoperative anxiety (Kain et al., 1996c).

Interventions

Preparation Programs

The impact of preparation programs on the incidence of postoperative behavioral changes is not clear. Vernon and Thompson (1993) completed a meta-analysis of published studies that evaluated the effects of preoperative behavioral preparation programs on postoperative behavior. The meta-analysis concluded that on the average, children who received preoperative interventions tended to have less postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes than did control subjects. In contrast, Kain et al. (1998a) compared several types of preoperative preparation programs in children and found no effect of preoperative preparation on the incidence of postoperative behavioral changes.

Parental Presence

The impact of parental presence during induction of anesthesia on the incidence of postoperative behavioral changes was evaluated (Kain et al., 1996b). To date, all studies concluded that the presence of a parent during induction does not have an impact on the issue of postoperative behavioral changes (Kain et al., 1996b; Kain, 2000).

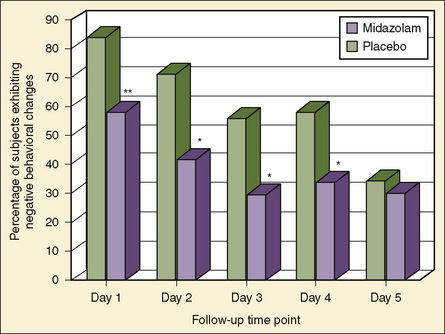

Sedatives

Investigations that looked into the association between preoperative sedative premedication and postoperative behavioral changes report contradictory findings. Two investigations report some beneficial effects of premedication on postoperative behavior, but others report no effect (Padfield et al., 1986; Parnis et al., 1992; Payne et al., 1992). Furthermore, an investigation found a higher incidence of negative postoperative behavioral changes in children who were premedicated (McGraw and Kendrick, 1998). These contradictory results may be explained by the methodologic complexity of this issue. Confounding variables such as the age of the child, surgical procedure, postoperative pain, and recent stressful major life events must be considered. An investigation by Kain and others (1999b) addressed all of these methodologic issues and screened all children for recent stressful life events. The investigators found that a significantly smaller number of children who were premedicated with oral midazolam before surgery demonstrated negative behavioral changes on postoperative days 1 through 7 (Fig. 8-11). Postoperative behaviors that were most improved included apathy and withdrawal, separation anxiety, and eating disturbances. At the second postoperative week, however, there were no significant differences between the placebo and midazolam groups. Thus, it can be concluded that in addition to its significant beneficial preoperative effects, sedative premedication improves immediate postoperative behavioral outcomes in young children undergoing general anesthesia and outpatient surgery.

Clinical Outcomes

Five decades ago, Janis (1958) proposed that moderate levels of preoperative anxiety in adult patients were associated with good postoperative behavioral recovery and that low and high levels of preoperative anxiety were associated with poor behavioral recovery. Although Janis’ theory is intriguing, his studies were based on descriptive data from nonrandom, limited samples and retrospective reports of questionable validity. Subsequent studies have been critical of Janis’ methodology and have reported a linear rather than a curvilinear relationship between anxiety level and postoperative behavioral recovery (Johnson et al., 1971; Johnston, 1980; Johnston and Carpenter, 1980; Newman, 1984; Pick et al., 1994). That is, low levels of preoperative anxiety are associated with good postoperative behavioral recovery, whereas high levels of preoperative anxiety are associated with poor postoperative behavioral recovery. To date, the literature on adults indicates that intensity of pain, analgesic requirements, postsurgical complications, length of hospital stay, poor patient satisfaction, and blood cortisol levels have all been reported to be associated with high levels of preoperative anxiety (Devine, 1992; Johnston and Vogele, 1993; Contrada et al., 1994; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1998).

Many reviews of this research have appeared that, although critical of the methodology of a large number of studies, concluded that high preoperative anxiety is associated with impaired postoperative recovery (Mumford et al., 1982; Mathews and Ridgeway, 1984; Rogers and Reich, 1986; Anderson, 1987; Suls and Wan, 1989; Johnston and Wallace, 1990; Kincey and Saltmore, 1990; Devine, 1992; Johnston and Vogele, 1993; Contrada et al., 1994; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1998).

The fact that low preoperative anxiety is predictive of good postoperative outcome underlies many interventions in which the aim is to reduce preoperative anxiety. As with the cohort studies described earlier, preparation studies have used diverse postoperative outcome measures, including pain, analgesic requirements, length of hospital stays, patient satisfaction, cortisol levels, blood pressure, heart rate, and behavioral indices of recovery (Mumford et al., 1982; Andersen and Masur, 1983; Mathews and Ridgeway, 1984; Anderson, 1987; Johnston and Vogele, 1993). Reviews of this research concluded that psychologically prepared adult patients have improved postoperative recovery results (Mumford et al., 1982; Suls and Wan, 1989; Johnston and Wallace, 1990; Devine, 1992; Johnston and Vogele, 1993; Contrada et al., 1994; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1998).

In contrast to the adult literature, there is a paucity of peer-reviewed, published-outcome data regarding the question of whether heightened preoperative anxiety impairs postoperative recovery in children undergoing surgery. A large-scale study assessed this question with convergent clinical, neuroendocrinologic, and behavioral measures and found that increased preoperative anxiety in children is associated with impaired postoperative behavioral and clinical recovery. Analysis of the data indicated that children who were more anxious preoperatively showed poorer immediate clinical recovery (Kain et al., 2002c). The study also found a significant relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain and postoperative behavioral recovery. That is, children who were more anxious preoperatively were in more pain postoperatively and had a higher incidence of postoperative behavioral changes. More recently, Kain and colleagues (2004a, 2006a) demonstrated that preoperative anxiety was a predictor of emergence delirium, postoperative anxiety and sleep problems, and new behavioral problems after surgery.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care. Child life programs. Pediatrics. 1993;91:671-673.

Andersen K.O., Masur F.T. Psychological preparation for invasive medical and dental procedures. J Behav Med. 1983;6:17-40.

Anderson E. Preoperative preparation for cardiac surgery facilitates recovery, reduces psychological distress, and reduces the incidence of acute postoperative hypertension. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:513-520.

Aono J., Mamiya K., Manabe M. Preoperative anxiety is associated with a high incidence of problematic behavior on emergence after halothane anesthesia in boys. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43:542-544.

Baeck E. The neural networks of music. Eur J Neurol. 2002;56:449-454.

Beeby D.G., Hughes J.O.M. Behaviour of unsedated children in the anaesthetic room. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:279-281.

Bevan J.C., Johnston C., Haig M.J., et al. Preoperative parental anxiety predicts behavioral and emotional responses to induction of anesthesia in children. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:177-182.

Bowie J.R. Parents in the operating room. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:1192-1193.

Braude N., Ridley S.A., Summer E. Parents and paediatric anaesthesia: a prospective survey of parental attitudes to their presence at induction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:41-44.

Brophy C.J., Erickson M.T. Children’s self-statements and adjustment to elective outpatient surgery. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1990;11:13-16.

Burton L. Anxiety relating to illness and treatment. In: Verma V., editor. Anxiety in children. New York: Methuen Croom Helm, 1984.

Buss A., Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. New York: Wiley-Interscience Publications, 1975.

Buss A., Plomin R., Willevuan L. The inheritance of temperament. J Pers. 1973;41:513-524.

Cassady J., Kain Z. Preoperative preparation for parents of pediatric surgery patients. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2000;1:10-17.

Cassady J.F.Jr, Wysocki T.T., Miller K.M., et al. Use of a preanesthetic video for facilitation of parental education and anxiolysis before pediatric ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:246-250.

Chapman A.H., Loeb D.G., Gibbons M.J. Psychiatric aspects of hospitalizing children. Arch Paediatr. 1956;73:77.

Chetta H.D. The effect of music and desensitization on preoperative anxiety in children. J Music Ther. 1981;18:74-87.

Cohen A. Environmental noise problems in broad perspective. In: Proceedings of Symposium on Environmental Noise-Its Human and Economic Effects. Chicago: Chicago Hearing Society; 1970.

Contrada R.J., Leventhal E.A., Anderson J.R.. Psychological preparation for surgery: marshalling individual and social resources to optimize self-regulation. Maes S., Leventhal H., Johnston M., editors. International review of health psychology, vol 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 1994.

Corman H., Hornick E., Kritchman M., et al. Emotional reactions of surgical patients to hospitalization, anesthesia and surgery. Am J Surg. 1958;96:646-653.

Davidson A.J., Shrivastava P.P., Jamsen K., et al. Risk factors for anxiety at induction of anesthesia in children: a prospective cohort study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16:919-927.

Devine E. Effects of psychoeducational care for adult surgical patients: a meta-analysis of 191 studies. Patient Educ Counsel. 1992;19:129-142.

Eckenhoff J.E. Relationship of anesthesia to postoperative personality changes in children. Am J Dis Child. 1958;86:587-591.

Egbert L., Battit G., Turndorf H., et al. The value of the preoperative visit by an anesthetist. JAMA. 1963;185:553-555.

Falk S.A., Woods N.F. Hospital noise: levels and potential health hazards. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:774-781.

Faust J., Melamed B. Influence of arousal, previous experience, and age on surgery preparation of same day of surgery and in-hospital pediatric patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:359-365.

Ford R.C., Bach S.A., Fottler M.D. Methods of measuring patient satisfaction in health care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev. 1997;22:74-89.

Fortier M.A., MacLaren Chorney J., Zisk Rony R.Y., et al. Children’s desire for perioperative information. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1085-1090.

Fung D., Cohen M.M. Measuring patient satisfaction with anesthesia care: a review of current methodology. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1089-1098.

Gardner W.J., Licklider J.C.R. Auditory analgesia in dental operations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1959;59:1144-1149.

Gardner W.J., Licklider J.C.R., et al. Suppression of pain by sound. Science. 1960;132:32-33.

Gauderer M.W., Lorig J.L., Eastwood D.W. Is there a place for parents in the operating room? J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:705-706.

Hannallah R.S., Rosales J.K. Experience with parents’ presence during anaesthesia induction in children. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1983;30:286-289.

Hickmott K.C., Shaw E.A., Goodyer I., et al. Anaesthetic induction in children: the effect of maternal presence on mood and subsequent behaviour. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1989;6:145-155.

Hodge B., Thompson J.F. Noise pollution in the operating theatre. Lancet. 1990;335:891-894.

Holm-Knudsen R.J., Carlin J.B., McKenzie I.M. Distress at induction of anaesthesia in children: a survey of incidence, associated factors and recovery characteristics. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:383-392.

Hsu D. Acupuncture: a review. Reg Anesth. 1996;21:361-370.

Hyson M. Going to the doctor: a developmental study of stress and coping. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 24, 1983.

Janis I.L. Psychological stress: Psychoanalytic and behavioral studies of surgical patients. New York: Wiley, 1958.

Johnson J.E., Leventhal H., Dabbs J.M.Jr. Contribution of emotional and instrumental response processes in adaptation to surgery. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1971;20:55-64.

Johnston M. Anxiety in surgical patients. Psychol Med. 1980;10:145-152.

Johnston M., Carpenter L. Relationship between pre-operative anxiety and post-operative state. Psychol Med. 1980;10:361-367.

Johnston M., Vogele C. Benefits of psychological preparation for surgery: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 1993;15:245-256.

Johnston M., Wallace L. Stress and medical procedures. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Kagan J., Reznick J.S., Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Dev. 1987;58:1459-1473.

Kain Z.N. Postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes in children: incidence, risks factors and interventions. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2000;51:217-226.

Kain Z.N. Parental presence and premedication revisited. Curr Opin Anesth. 2001;14:331-337.

Kain Z.N., Andrews-Caldwal A., Wang S. Psychological preparation of the pediatric surgical patient. Anesth Clin North Am. 2002;20:29-44.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A., Blount R., et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia: the development of a new intervention. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:A1242.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., LoDolce M.E., et al. The perioperative behavioral stress response in children. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:A1242.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., Alexander G.M., et al. Sleeping characteristics of children undergoing outpatient elective surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1093-1101.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Maranets I., et al. Preoperative anxiety and emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1648-1654.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Krivutza D.M., et al. Interactive music therapy as a treatment for preoperative anxiety in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1260-1266.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Krivutza D., et al. Trends in the practice of parental presence during induction of anesthesia and the use of preoperative sedative premedication in the United States, 1995–2002: results of a follow-up national survey. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1252-1259.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Maranets I., et al. Predicting which child-parent pair will benefit from parental presence during induction of anesthesia: a decision-making approach. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:81-84.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., et al. Preoperative anxiety, postoperative pain, and behavioral recovery in young children undergoing surgery. Pediatrics. 2006;118:651-658.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., et al. Predicting which children benefit most from parental presence during induction of anesthesia. Pedatr Anesth. 2006;16:627-634.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Mayes L.C., et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia: physiological effects on parents. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:58-64.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Wang S-M., et al. Parental intervention choices for children undergoing repeated surgeries. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:970-975.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Mayes L.C., et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:65-74.

Kain Z.N., Caldwell-Andrews A.A., Weinberg M.E., et al. Sevoflurane versus halothane: postoperative maladaptive behavioral changes. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:720-726.

Kain Z.N., Caramico L., Mayes L., et al. Preoperative preparation programs in children: a comparative study. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1249-1255.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Wang S., et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia vs. sedative premedication: which intervention is more effective? Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1147-1156.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L. Anxiety in children during the perioperative period. In: Borestein M., Genevro J., editors. Child development and behavioral pediatrics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Caramico L., et al. Social adaptability and other personality characteristics as predictors for children’s reactions to surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2001;12:549-554.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Caramico L., et al. Distress during induction of anesthesia and postoperative behavioral outcomes. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1042-1047.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Caramico L., et al. Postoperative behavioral outcomes in children: effects of sedative premedication. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:758-765.

Kain Z.N., Hernandez Conte A., Kosarusavadi B., et al. Desire for information in adult patients: a cross sectional study. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:467-472.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Cicchetti D., et al. The Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale: how does it compare to a gold standard? Anesth Analg. 1997;85:783-788.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., Bell C., et al. Premedication in the United States: a status report. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:427-432.

Kain Z.N., Wang S.M., Caramico L.A., et al. Parental desire for perioperative information and informed consent: a two-phase study. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:299-306.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Cicchetti D., et al. Measurement tool for pre-operative anxiety in children: the Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale. Child Neuropsychol. 1995;1:203-210.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L., Wang S., et al. Parental presence and a sedative premedicant for children undergoing surgery: a hierarchical study. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:939-946.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., Caramico L.A. Preoperative preparation in children: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8:508-514.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., Caramico L.A., et al. Parental presence during induction of anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1060-1067.

Kain Z.N., Mayes L.C., O’Connor T.Z., et al. Preoperative anxiety in children: predictors and outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:1238-1245.

Kain Z.N., MacLaren J.E., Hammell C., et al. Healthcare provider-child-parent communication in the preoperative surgical setting. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:376-384.

Kain Z.N., Maclaren J., Weinberg M., et al. How many parents should we let into the operating room? Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:244-249.

Kain Z.N., Rimar S., Barash P.G. Cocaine abuse in the parturient and effects on the fetus and neonate. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:835-845.

Kane E. The phonograph in the operating room. JAMA. 1914;62:1829.

Karl H.W., Pauza K.J., Heyneman N., et al. Preanesthetic preparation of pediatric outpatients: the role of a videotape for parents. J Clin Anesth. 1990;2:172-177.

Kerrigan D.D., Thevasagayam R.S., Woods T.O., et al. Who’s afraid of informed consent? BMJ. 1993;306:298-300.

Kiecolt-Glaser J.K., Page G., Marucha P., et al. Psychological influences on surgical recovery. Am Psychol. 1998;53:1209-1218.

Kincey J., Saltmore S. Surgical treatments. In: Johnston M., Wallace L., editors. Stress and medical procedures. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Kotiniemi L., Ryhanen P. Behavioural changes and children’s memories after intravenous, inhalation and rectal induction of anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:201-207.

Kotiniemi L.H., Ryhanen P.T., Moilanen I.K. Behavioural changes following routine ENT operations in two-to-ten-year-old children. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:45-49.

Kotiniemi L.H., Ryhanen P.T., Moilanen I.K. Behavioural changes in children following day-case surgery: a 4-week follow-up of 551 children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:970-976.

Kotiniemi L.H., Ryhanen P.T., Valanne J., et al. Postoperative symptoms at home following day-case surgery in children: a multicentre survey of 551 children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:963-969.

Lerman J. Anxiolysis: by the parent or for the parent? Anesthesiology. 2000;92:925.

Levy D. Psychic trauma of operations in children. Am J Dis Child. 1945;69:7-25.

Lewyn M.J. Should parents be present while their children receive anesthesia? May. Anesth Malpract Protect. 1993:56-57.

Lipe A. Beyond therapy: music, spirituality, and health in human experience: a review of literature. J Music Ther. 2002;39:209-240.

Litman R., Berger A., Chhibber A. An evaluation of preoperative anxiety in a population of parents of infants and children undergoing ambulatory surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 1996;6:443-447.

Lumley M., Abeles L., Melamed B., et al. Coping outcomes in children undergoing stressful medical procedures: the role of child-environment variables. Behav Assess. 1990;12:223-238.

Lumley M.A., Melamed B.G., Abeles L.A. Predicting children’s presurgical anxiety and subsequent behavior changes. J Pediatr Psychol. 1993;18:481-497.

Macario A., Weinger M., Truong P., et al. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are both common and important to avoid? The perspective of a panel of expert anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1085-1091.

MacLaren J.E., Thompson C., Weinberg M., et al. Prediction of preoperative anxiety in children: who is most accurate? Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1777-1782.

Manley C. Elective genital surgery at one year of age: psychological and surgical considerations. Surg Clin North Am. 1982;62:941-953.

Mathews A., Ridgeway V. Psychological preparation for surgery. In: Steptoe A., Mathews A., editors. Health care and human behaviour. London: Academic Press, 1984.

McGraw T., Kendrick A. Oral midazolam premedication and postoperative behavior in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:117-121.

Melamed B., Meyer R., Gee C., et al. The influence of time and type of preparation on children’s adjustment to hospitalization. J Pediatr Psychol. 1976;1:31-37.

Melamed B.G. Putting the family back in the child. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:239-247.

Melamed B.G., Dearborn M., Hermecz D.A. Necessary considerations for surgery preparation: age and previous experience. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:517-525.

Melamed B.G., Ridley-Johnson R. Psychological preparation of families for hospitalization. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1988;9:96-102.

Melamed B.G., Siegel L.J. Reduction of anxiety in children facing hospitalization and surgery by use of filmed modeling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975;43:511-521.

Melamed B.G., Yurcheson R., Fleece E.L., et al. Effects of film modeling on the reduction of anxiety-related behaviors in individuals varying in level of previous experience in the stress situation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:1357-1367.

Mellish R.W.P. Preparation of a child for hospitalization and surgery. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1969;16:543-553.

Meyers E.F., Muravchick S. Anesthesia induction technics in pediatric patients: a controlled study of behavioral consequences. Anesth Analg. 1977;56:538-542.

Miller S., Mangan C. Interacting effects of information and coping style in adapting to gynecologic stress: should the doctor tell all? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;45:223-226.

Miller S.M. Monitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their disease: implications for cancer screening and management. Cancer. 1995;76:167-177.

Miluck-Kolasa B., Matejek M., Stupnicki R. The effects of music listening on changes in selected physiological parameters in adult presurgical patients. J Music Ther. 1996;33:208-218.

Mumford E., Schlesinger H.J., Glass G.V. The effects of psychological intervention on recovery from surgery and heart attacks: an analysis of the literature. Am J Pub Health. 1982;72:141-151.

Newman S. Anxiety, hospitalization, and surgery. In: Fitzpatrick R., Hinton J., Newman S., et al, editors. The experience of illness. London: Tavistock Publications, 1984.

Nott M., West P. Orthopaedic theatre noise: a potential hazard to patients. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:784-787.

O’Byrne K., Peterson L., Saldana L. Survey of pediatric hospitals’ preparation programs: evidence of the impact of health psychology research. Health Psychol. 1997;16:147-154.

Padfield N.L., Twohig M., Fraser A.C.L. Tempazepam and trimeprazine compared with placebo as premedication in children. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:487-493.

Parnis S.J., Foate J.A., van-der-Walt J.H., et al. Oral midazolam is an effective premedication for children having day-stay anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1992;20:9-14.

Payne K.A., Coetzee A.R., Mattheyse F.J., et al. Behavioural changes in children following minor surgery: is premedication beneficial? Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1992;43:173-179.

Peterson L., Shigetomi C. One-year follow-up of elective surgery child patients receiving preoperative preparation. J Pediatr Psychol. 1982;7:43-48.

Piaget J. The language and thought of the child. New York: Meridian Books, 1955.

Pick B., Molloy A., Hinds C., et al. Post-operative fatigue following coronary artery bypass surgery: relationship to emotional state and to the catecholamine response to surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:599-607.

Pinto R.P., Hollandsworth J.G.Jr. Using videotape modeling to prepare children psychologically for surgery: influence of parents and costs versus benefits of providing preparation services. Health Psychol. 1989;8:79-95.

Robb S.L., Nichols R.J., Rutan R.L., et al. The effects of music assisted relaxation on preoperative anxiety. J Music Ther. 1995;32:2-21.

Robinson P.J., Kobayashi K. Development and evaluation of a presurgical preparation program. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:193-212.

Rogers M., Reich P.. Psychological intervention with surgical patients: evaluation outcome. Fava G., Guggenheim F.G., Lipowski Z.J., et al, editors. Psychological aspects of surgery, 15. Basel: Karger, 1986.

Ryder I., Spargo P. Parents in the anesthetic room: a questionnaire survey of parents’ reactions. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:977-979.

Schofield N.M., White J.B. Interrelations among children, parents, premedication, and anaesthetists in paediatric day stay surgery. BMJ. 1989;299:1371-1375.

Schulman J.L., Foley J.M., Vernon D.T., et al. A study of the effect of the mother’s presence during anesthesia induction. Pediatrics. 1967;39:111-114.

Shirley P., Thompson N., Kenward M., et al. Parental anxiety before elective surgery in children. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:956-959.

Sparrow S.S., Balla D.A., Cicchetti D.V. Manual for the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines: American Guidance Services, 1984.

Standley J.M. Music research in medical/dental treatment: meta-analysis and clinical applications. J Music Ther. 1986;23:56-122.

Suls J., Wan C.K. Effects of sensory and procedural information on coping with stressful medical procedures and pain: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:372-379.

Thompson J.F., Kam P.C. Music in the operating theatre [editorial]. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1586-1587.

Thompson R., Vernon D. Research on children’s behavior after hospitalization: a review and synthesis. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:28-35.

Vernon D., Foley J., Sipowicz R., et al. The psychological responses of children to hospitalization and illness. Springfield, IL: Thomas Books, 1965.

Vernon D., Thompson R. Research on the effect of experimental interventions on children’s behavior after hospitalization: a review and synthesis. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:36-44.

Vernon D.T., Schulman J.L., Foley J.M. Changes in children’s behavior after hospitalization. Am J Dis Child. 1966;111:581-593.

Vessey J.A., Bogetz M.S., Caserza C.L., et al. Parental upset associated with participation in induction of anaesthesia in children. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:276-280.

Vetter T. The epidemiology and selective identification of children at risk for preoperative anxiety reactions. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:96-99.

Wang S., Caldwell-Andrews A., Kain Z. The use of complementary and alternative medicines by surgical patients: a follow-up survey study. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1010-1015.

Wang S., Gaal D., Maranets I., et al. Acupressure and preoperative parental anxiety: a pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:666-669.

Wang S., Kain Z. Acupuncture as a treatment for preoperative anxiety. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1178-1180.

Wang S., Kain Z. Auricular acupuncture: a potential treatment for anxiety. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:548-553.

Wang S., Kulkarni L., Dolev J., et al. Music and preoperative anxiety: a randomized controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1489-1494.

Wang S., Peloquin C., Kain Z. Attitudes of patients undergoing surgery toward alternative medical treatment. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:351-356.

Wang S., Maranets I., Weinberg M., et al. Parental auricular acupuncture as an adjunct for parental presence during induction of anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(6):1399-1404.