Chapter 19 Psychologic Treatment of Children and Adolescents

The provision of supportive counseling, anticipatory guidance, and parent psychoeducation (Chapter 5) combined with medication management of noncomplex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and pervasive developmental disorders are commonly undertaken in the medical home. Youngsters with complex and co-occurring psychiatric illnesses require intervention from specially trained mental health clinicians.

19.1 Psychopharmacology

To ensure safe and appropriate use of psychotropic medications, prescribers should follow best practice principles that underlie medication prescribing (Table 19-1). The use of medication involves a series of interconnected steps including performing an assessment, deciding on treatment and a monitoring plan, obtaining treatment assent or consent, and implementing treatment. Cognitive, emotional, and/or behavior symptoms are targets for medication intervention when there is no response to available evidence-based psychosocial interventions, there is a significant risk of harm, and/or there is significant functional impairment. Commonly encountered target symptom domains include agitation, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, inattention, impulsivity, mania, and psychosis (Table 19-2).

Table 19-1 CLINICAL APPROACH TO PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Modified from Myers SM, Johnson CP, American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities: Management of children with autism spectrum disorders, Pediatrics 120:1162–1182, 2007.

Table 19-2 TARGET SYMPTOM APPROACH TO PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

| TARGET SYMPTOM | MEDICATION CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

| Agitation |

Modified from Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR: Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents, Washington, DC, 2006, American Psychiatric Press, p 306.

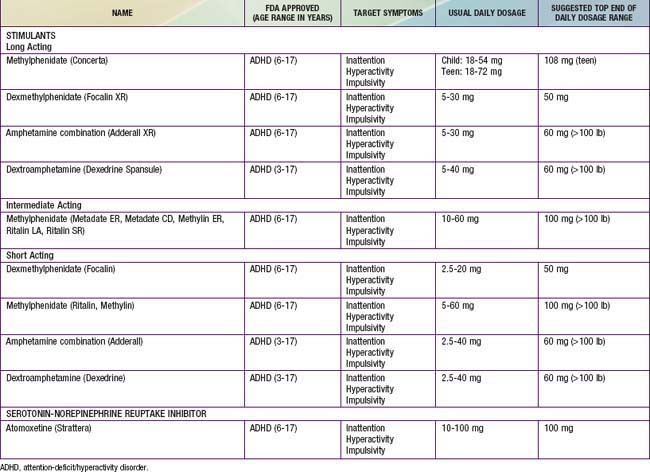

Stimulants

Stimulants are sympathomimetic drugs that act both in the central nervous system and peripherally by enhancing dopaminergic and noradrenergic transmission (Table 19-3). These medications are used to treat ADHD (Chapter 30) and in some cases as an adjunct in the treatment of depression and for fatigue or malaise associated with chronic physical illnesses. There is a range of stimulant options including those with short half-lives (typically 4 hr) and those with long half-lives (8-12 hr). The most commonly reported side effects are appetite suppression and sleep disturbances. Irritability, headaches, stomachaches, lethargy, hallucinations, and fatigue have also been reported. Anorexia and weight loss have been noted with controversy about their impact on ultimate growth in height.

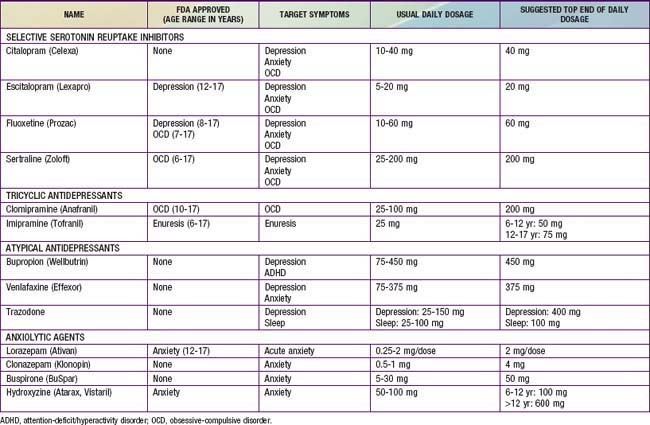

Antidepressants

Antidepressant drugs act on pre- and postsynaptic receptors affecting the release and reuptake of brain neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine (Table 19-4). These medications have been useful in the treatment of depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first line of medication treatment for anxiety and depressive disorders; the evidence supports a higher degree of efficacy for anxiety compared to depression. They have a large margin of safety with no cardiovascular effects. Side effects include irritability, insomnia, appetite changes, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, diaphoresis, restlessness, and sexual dysfunction (Chapter 58). Withdrawal symptoms are more common in short-acting SSRIs. Behavioral activation and suicidal thoughts have been reported. This has led to recommendations for close monitoring for these adverse effects, especially in the 1st wks of treatment.

The tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have mixed mechanisms of action (e.g., clomipramine is primarily serotonergic; imipramine is both noradrenergic and serotoninergic). With the advent of the SSRIs, the lack of efficacy studies (particularly in depression), and more serious side effects, the use of TCAs in children has declined. They continue to be used in the treatment of some anxiety disorders (particularly obsessive-compulsive disorder) and, unlike the SSRIs, can be helpful in pain disorders. They have a narrow therapeutic index, with overdoses being potentially fatal (Chapter 58). Anticholinergic symptoms (e.g., dry mouth, blurred vision, and constipation) are the most common side effects. TCAs can have cardiac conduction effects in doses higher than 3.5 mg/kg. Blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring is indicated at doses above this level.

The atypical antidepressants include bupropion, venlafaxine, and trazodone (see Table 19-4); they are second-line medications for anxiety and depressive disorders. Bupropion has also been used for smoking cessation and ADHD. Bupropion appears to have an indirect mixed agonist effect on dopamine and norepinephrine transmission. Common side effects include irritability, nausea, anorexia, headache, and insomnia. Venlafaxine has both serotonergic and noradrenergic properties. Side effects are similar to SSRIs, including irritability, insomnia, headaches, anorexia, nervousness, dizziness, and blood pressure changes. Trazodone also has a mixed mechanism of action, with serotonergic and anti-α-adrenergic properties. Sedation is its most common side effect, leading to its common use for insomnia.

Anxiolytic agents (including lorazepam, clonazepam, buspirone, and hydroxyzine) have all been effectively used for acute situational anxiety (see Table 19-4). Their efficacy as chronic medication is poorer, particularly when used as a monotherapy agent.

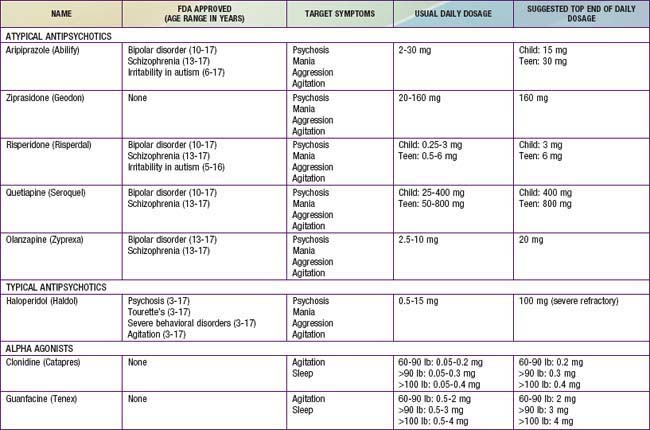

Antipsychotics

Based on their mechanism of action, antipsychotic medication can be divided into typical (blocking dopamine D2 receptor) and atypical (mixed dopaminergic and serotoninergic (5-HT2) activity) agents (Table 19-5).

α-Adrenergic Agents

The α-adrenergic agents (clonidine and guanfacine) are presynaptic adrenergic agonists that appear to stimulate inhibitory presynaptic autoreceptors in the central nervous system. Although most commonly used in Tourette’s disorder and ADHD, these agents may be useful in controlling aggression, particularly in patients with developmental disorders (see Table 19-5). Sedation, hypotension, dry mouth, depression, and confusion are potential side effects. Abrupt withdrawal can result in rebound hypertension. Guanfacine appears to be less sedating and to have a longer duration of action than clonidine.

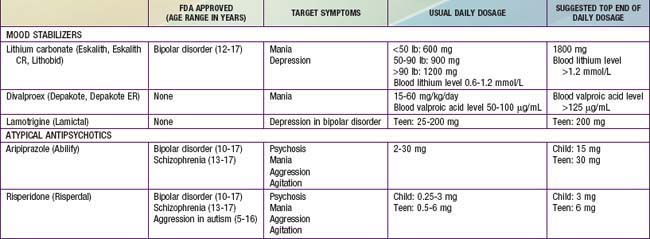

Mood Stabilizers

Several medications have been shown to be potentially helpful in children experiencing significant mood instability and/or mania, although the evidence base is sparse (Table 19-6).

Medication Use in Physical Illness

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare and potentially fatal reaction that can occur during treatment with antipsychotic agents (Chapter 169). The syndrome generally manifests with fever, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability, and delirium. It is associated with elevated serum creatine phosphokinase levels, a metabolic acidosis, and high end-tidal CO2 excretion. It has been estimated to occur in 0.2-1% of patients treated with dopamine-blocking agents. Malnutrition and dehydration in the context of an organic brain syndrome and simultaneous treatment with lithium and antipsychotic agents can increase the risk. Mortality rates may be as high as 20-30% due to dehydration, aspiration, kidney failure, and respiratory collapse. Differential diagnosis of NMS includes heat stroke, malignant hyperthermia, lethal catatonia, serotonin syndrome, and anticholinergic toxicity

Serotonin Syndrome

Serotonin syndrome is characterized by a triad of mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities (Chapter 58). It is the result of an excess agonism of the central and peripheral nervous system serotoninergic receptors and can be caused by a range of drugs including SSRIs, valproate, and lithium. Drug-drug interactions that can cause serotonin syndrome include linezolid (an antibiotic that has MAOI properties) and anti-migraine preparations used with an SSRI, as well as combinations of SSRI, trazodone, buspirone, and venlafaxine. It is generally self-limited and can resolve spontaneously after the serotoninergic agents are discontinued. Severe cases require the control of agitation, autonomic instability, and hyperthermia as well as the administration of 5-HT2A antagonists (e.g., cyproheptadine).

Frazier JA, Bregman HA, Jackson JA. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of early-onset bipolar disorder. In: Geller B, Delbello MP, editors. Treatment of bipolar illness in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2008:69-108.

Green WH. Child and adolescent clinical psychopharmacology, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Hamernedd PG, Geller DA. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pediatric psychopharmacology: a review of the evidence. J Pediatr. 2006;48:58-65.

Myers SM, Johnson CP. American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities: Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162-1182.

Parikh SV. Antidepressants are not all created equal. Lancet. 2009;373:700-701.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:225-235.

Rosenheck RA, Krystal JH, Lew R, et al. Long-acting risperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:842-850.

Scahill L, Oesterheld JR, Martin A. General principles, specific drug treatments, and clinical practice. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, editors. Lewis’ child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:754-788.

Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR. Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2006.

19.2 Psychotherapy

Shapiro JP, Friedberg RD, Bardenstein KK. Child and adolescent therapy: science and art. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006.

Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR. Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2006.