Psychiatric disorders and thyroid disease

1. How well established is the relationship between thyroid disease and psychiatric symptoms?

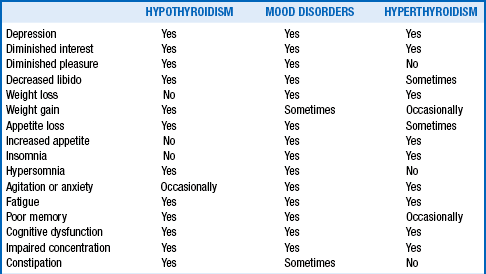

Since the publication of the Clinical Society of London’s “Report on Myxoedema” in 1888, it has been recognized that thyroid disease may give rise to psychiatric disorders that can be corrected by reestablishment of normal thyroid hormone levels. Later, Asher reemphasized that patients with profound hypothyroidism may present with depressive psychosis. As outlined in Table 41-1, the symptoms of hypothyroidism often mimic those of depression, whereas those of hyperthyroidism include anxiety, dysphoria, emotional lability, and intellectual dysfunction, as well as mania or depression, the latter especially characteristic among elderly patients presenting with apathetic thyrotoxicosis.

TABLE 41-1.

CLINICAL FEATURES COMMON TO BOTH THYROID DISEASES AND MOOD DISORDERS

Adapted from Hennessey JV, Jackson IMD: The interface between thyroid hormones and psychiatry. Endocrinologist 6:214–223, 1996.

2. What abnormalities of thyroid function are found in psychiatric disorders?

Because patients with thyroid disease may manifest frank psychiatric disorders that are reversible with endocrine therapy, the thyroid axis has been extensively studied in patients presenting with a wide variety of behavioral disturbances. Various abnormalities of thyroid function have been identified, particularly in depression. In most depressed subjects, the basal serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3) levels are within the normal range, although in one report, a third of such patients were observed to have suppressed TSH levels.

3. What abnormalities of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation test may be observed in depressed patients?

A “blunted” TSH response to TRH administration (defined as a TSH rise < 5 mU/L) is seen in approximately 25% of depressed subjects. The blunted TSH response is said to be observed more often in unipolar than bipolar depression, but differentiating these disorders with TRH testing has been disappointing. The blunted TSH response is a “state” marker that normalizes on recovery from depression.

4. Describe a mechanism for the blunted TSH response to TRH in affective disorders.

The mechanism for the blunted TSH response in affective disorders is not known; however, glucocorticoids, known to inhibit the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, are elevated in depression and could be responsible. This suppressed TSH response is not specific to depression and may be observed in alcohol withdrawal, starvation, normal male aging, renal failure, acromegaly, Cushing’s syndrome, and hypopituitarism. The blunting may also result from medications such as T4, glucocorticoids, growth hormone, somatostatin, dopamine, and phenytoin, all of which have been reported to diminish this response.

5. Can abnormalities in the TSH circadian rhythm be identified in depression?

In normal subjects, TSH begins to rise in the evening before the onset of sleep and reaches a peak between 11:00 pm and 4 am. In depression, the nocturnal TSH surge is frequently absent, resulting in reduced thyroid hormone secretion. This finding supports the view that functional central hypothyroidism may occur in some depressed subjects. Sleep deprivation, which has an antidepressant effect, returns the TSH circadian rhythm to normal. The mechanism for the impaired nocturnal TSH rise is unknown.

6. Is autoimmune thyroid disease frequently present in the depressed patient?

Although the blunted TSH response is well recognized in depression, it is less clearly appreciated that an enhanced TSH response may occur in up to 15% of depressed subjects with normal baseline thyroid function tests. Most such patients have antithyroid antibodies, a finding suggesting that the TSH hyperresponse may indicate latent hypothyroidism caused by autoimmune thyroiditis. When autoimmunity is tested using the antithyroid peroxidase antibody (anti-TPO) rather than the less specific antimicrosomal antibody, the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease is even higher. Not all studies, however, have found an increased prevalence of antithyroid antibodies in depressed subjects when compared with matched control groups.

7. What is the frequency of elevated T4 values in psychiatric patients?

Approximately 20% of patients admitted to a hospital with acute psychiatric presentations, including schizophrenia and major affective disorders, but rarely dementia or alcoholism, may demonstrate mild elevations in their serum T4 levels and, less often, T3 levels. The basal TSH is usually normal but may demonstrate blunted TRH responsiveness in up to 90% of such patients. These findings do not appear to represent thyrotoxicosis, and the abnormalities spontaneously resolve within 2 weeks without specific therapy. Such phenomena may be secondary to central activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis resulting in enhanced TSH secretion with consequent elevation in circulating T4 levels.

8. What is the most consistent abnormality of the thyroid axis in hospitalized depressed patients?

In depressed patients, the most consistent abnormality of the thyroid axis may be an increase in serum total or free T4 levels, although usually within the conventional reference range. This elevation generally regresses following successful treatment of the depression.

9. What is the prevalence of hypothyroid dysfunction in psychiatric populations?

Thyroid function test abnormalities are common in older individuals. In otherwise normal female patients who are more than 60 years old, the prevalence of elevated TSH values and/or positive antithyroid antibodies is 10% or more. Subjecting apparently asymptomatic individuals with slight elevations of serum TSH but normal T4 and T3 levels to a battery of psychological tests has revealed significant differences from control subjects on scales measuring memory, anxiety, somatic complaints, and depression in many but not all studies reported. It is becoming increasingly recognized that depression is much more common in elderly individuals. Whether borderline hypothyroidism plays a role in these behavioral disturbances requires clinical attention. Further investigation should also be directed at studying the outcomes of intervention with levothyroxine.

Among alcoholic patients and those suffering from anorexia nervosa, suppressed T3 levels with elevations in reverse T3 and normal TSH values are consistent with the euthyroid sick syndrome. These findings likely result from caloric deprivation.

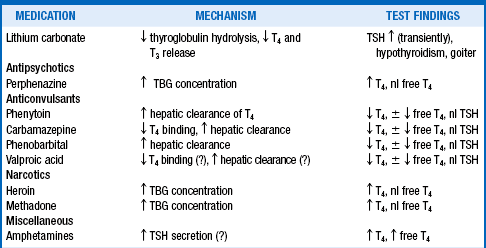

10. Which medications affect thyroid function and thyroid function tests?

Medications commonly used to treat psychiatric illness have been shown to affect thyroid function tests (Table 41-2).

TABLE 41-2.

IMPACT OF PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS ON THYROID FUNCTION TESTS

Adapted from Hennessy JV, Jackson IMD: The interface between thyroid hormones and psychiatry. Endocrinologist 6:214–223, 1996.

11. How does lithium affect the pituitary-thyroidal axis?

Lithium carbonate, used to treat bipolar disorders, interferes with both the release and organification of thyroid hormone. Therapeutic lithium levels diminish both T3 and T4 release from the thyroid gland, whereas at higher (probably toxic) levels, iodine uptake and organification may also be inhibited. Following a 3-week therapeutic course of lithium carbonate, suppression of serum T4 and T3 levels and associated elevations of basal serum TSH values and exaggerated TSH responses to TRH administration may be noted; these abnormalities generally return to normal within 3 to 12 months, even if the medication is continued.

12. What is the most common thyroid disorder in lithium-treated patients?

Goiter is the most common thyroid disorder in lithium-treated patients. Hypothyroidism can also occasionally develop, particularly in patients who have thyroid glands that have been compromised by disorders such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease previously treated with 131-iodine therapy. However, it is uncommon for hypothyroidism to occur if pretreatment thyroid function was completely normal and patients are thyroid antibody negative. If considered clinically necessary, lithium may be continued and T4 added to treat patients who develop goiter or hypothyroidism.

13. How does phenytoin affect laboratory tests and the function of the thyroid?

The effects of phenytoin (Dilantin), occasionally used for bipolar disorder, on thyroid function are quite complex. Suppressed values of total T4 and, occasionally, free T4 are observed in a significant minority of patients who are treated on a long-term basis with phenytoin alone and in more than 75% of patients in whom the drug is combined with carbamazepine (Tegretol). The lower total T4 levels are likely secondary to displacement of T4 from thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), whereas the reduced free T4 levels result from enhanced clearance of T4 through phenytoin-induced hepatic microsomal oxidative enzyme activity. Generally, the suppressed T4 levels are accompanied by normal T3 and free T3 levels and normal TSH concentrations. Normal basal TSH values with diminished TSH responses to TRH have been attributed to potential phenytoin agonism at the T3 receptor. However, other studies have suggested that this may be an assay artifact because free T4 values have been found to be normal or mildly elevated in analyses using undiluted serum.

14. Describe the effects of carbamazepine on thyroid function.

Carbamazepine (Tegretol) is used increasingly in bipolar disorder. Long-term use with maintenance of therapeutic serum levels suppresses serum T4 values in more than 50% of patients. This may be the result of enhanced hepatic metabolism of T4. TRH stimulation testing before and after initiation of carbamazepine therapy reveals that TSH responsiveness is reduced by the addition of this drug; this finding has led to speculation that carbamazepine may inhibit thyroid function through effects on the pituitary gland. Displacement of T4 from TBG, similar to that seen with phenytoin, has additionally been cited as a potential effect.

15. How do phenobarbital, valproic acid, and other psychotropic medications affect thyroid function?

Both phenobarbital and valproic acid are reported to lower serum levels of T4 in patients treated on a long-term basis, the former via enhanced hepatic T4 clearance and the latter likely from protein binding changes. Heroin, methadone, and perphenazine commonly increase serum TBG levels and therefore may elevate serum total T4 levels, although TSH and free T4 values remain normal. Amphetamines induce hyperthyroxinemia through enhanced secretion of TSH, an effect that appears to be centrally mediated.

16. How do antidepressant therapies affect thyroid function?

Antidepressants do not generally cause abnormal peripheral thyroid hormone levels but may affect thyroid hormone metabolism in the central nervous system (CNS). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) appear to promote activity of type 2 deiodinase (D2), which increases conversion of T4 into T3 in the brain. However, peripheral circulating total T4 and free T4 levels, often show a modest decline, though still within the normal range after treatment with various pharmacologic classes of antidepressants, or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). There are case reports of sertraline-, paroxetine-, and escitalopram-related asymptomatic hypothyroidism, but more recent studies evaluating fluoxetine and sertraline have shown no clinically significant change in thyroid function test results.

17. Are there caveats for antidepressant use in individuals with thyroid disease?

The use of TCAs in thyrotoxic patients should be pursued with caution because cardiac dysrhythmias may be exacerbated or precipitated. Further, the monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors may cause hypertension in thyrotoxic patients, although these drugs generally do not affect thyroid function or serum thyroid hormone levels.

18. Has T4 been used as sole treatment for depression?

Asher’s report on “myxoedematous madness” demonstrated that thyroid hormone deficiency resulted in depression that reversed with thyroid hormone administration. This led to studies of the role of thyroid hormone therapy alone in the treatment of depression and other psychiatric diseases and open studies of high-dose T4 for refractory bipolar and unipolar depression. Euthyroid individuals with typical hypothyroid symptoms who are considered depressed on psychological testing do not improve when treated with T4. In fact, patients presenting with symptoms of hypothyroidism with normal thyroid function test results respond more positively to placebo. Although initial reports of T3 as single therapy were promising, these studies were methodologically flawed, so the role of thyroid hormone by itself in the treatment of depression in the absence of abnormal thyroid function has not been established.

19. Are neuropsychiatric abnormalities demonstrable among patients with mild thyroid failure?

Studies have shown that symptomatic patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (elevated serum TSH but normal T4 and T3 levels) can have significant impairment of memory-related abilities, health status, and mood, as well as anxiety, somatic complaints, and depressive features, when compared with euthyroid controls. Greater than 60% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism report some degree of depressive symptoms. Effects of treatment with levothyroxine have been mixed. Some studies suggested that normalization of thyroid function with levothyroxine therapy, as determined by the serum TSH, may completely reverse these neuropsychiatric features. Conversely, other studies suggested that hypothyroid patients receiving levothyroxine replacement may continue to experience neuropsychiatric abnormalities despite a normal TSH when compared with controls of similar age and sex. Further, when thyroid hormone is withdrawn from subjects with underlying hypothyroidism, gradually increasing cognitive deficits, sadness, and anxiety symptoms are observed over the ensuing few weeks. These findings indicate that the patient presenting with depression must be assessed for thyroid dysfunction because the presence of even subclinical hypothyroidism may provide an opportunity for resolution of the depression with thyroid hormone treatment.

20. How effective is the combination of levothyroxine and liothyronine in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of hypothyroidism?

Murray introduced thyroid hormone therapy to the clinical world in 1891. From the beginning, this was a treatment based on a combination of T4 and T3 derived from animal thyroid extracts. Variability of the animal extracts in regard to T4 and T3 content and ratios from batch to batch and brand to brand led to the replacement of “natural” combination therapy using extracts with pharmaceutically more precise synthetic T4 and T3. Eventually, the simplicity of T4 monotherapy was adopted as usual therapy. The T4 dosage was titrated based on symptoms until more sensitive TSH assays became available. During the 1980s, sensitive TSH assays allowed titration of thyroid hormone therapy to “normal,” and this resulted in significant dose reductions of as much as 100 μg per day. Once euthyroid, however, some patients continued to complain of symptoms consistent with some components of hypothyroidism. Since that time, multiple reports have appeared evaluating the effectiveness of combining T3 with T4 to improve neuropsychological outcomes. The 1999 report of Bunevicius et al, for example, seemed to indicate that substituting 12.5 μg of T3 for 50 μg of the individual’s usual T4 dose resulted in improvement in mood and neuropsychological function. Several double-blind randomized controlled trials designed to correct design flaws of previous trials subsequently failed to reproduce the positive effects reported by Bunevicius et al and did not demonstrate improvement in self-rated mood, well-being, or depression scales with the addition of T3 to T4 therapy. Moreover, these studies failed to demonstrate differences in cognitive function, quality of life, or subjective satisfaction with treatment, but they did report that anxiety scores were significantly worse in patients treated with the T4-T3 combination. However, a subset of patients may benefit from T3 supplementation. Preliminary evidence suggests that patients with certain mutations in the D2 gene may have a positive response to T3 potentiation, but prospective trials have not yet been conducted. At this time, it does not appear justified to use combined T4 and T3 treatment in hypothyroid patients who complain of depressive symptoms after biochemical euthyroidism is restored.

21. Can combination antidepressant medication and thyroid hormone enhance the response to depression treatment?

Adjuvant therapy has been said to be logical when depression fails to resolve after 6 weeks of adequate antidepressant medication. Such resistance occurs in about 30% to 45% of cases. The role of adjuvant thyroid hormone with TCAs has been investigated in euthyroid patients with depression for more than 25 years. T3 doses of 25 to 50 μg daily increase serum T3 levels and cause suppression of serum TSH and T4 values. Two separate therapeutic effects of T3 therapy have been studied: first, its ability to accelerate the onset of the antidepressant response; and second, its ability to augment antidepressant responses among those considered pharmacologically resistant.

22. How effective is thyroid hormone for the acceleration of the antidepressant response?

Given that the antidepressant effect of TCAs is known to be delayed, the role of T3 in accelerating the therapeutic onset of these drugs has been investigated. Several reports detailing the clinical outcomes of starting T3 (5-40 μg daily) along with varying doses of TCAs, as well as SSRIs, at the outset of therapy have appeared in the literature. The study populations were inhomogeneous, consisting of patients with various types of depression. Furthermore, the studies had important methodologic limitations, including small sample sizes, inadequate medication doses, lack of serum medication level monitoring, and variable outcome measures. Because two relatively large, prospective, randomized placebo-controlled studies came to opposite conclusions, it still has not been clearly established that T3 accelerates the antidepressant effect of TCAs. A meta-analysis of double-blind clinical trials comparing SSRI-T3 treatment with SSRIs alone showed no significant difference in remission rates.

23. Can T3 therapy augment the clinical antidepressant response?

An additional hypothesis is that adding small doses of T3 to the antidepressant therapy of patients who have little or no initial response will enhance the clinical effectiveness of the antidepressant. Resistance to antidepressants is defined as inadequate remission after 2 successive trials of monotherapy with different antidepressants in adequate doses, each for 4 to 6 weeks before changing to alternative therapies. However, a course of 8 to 12 weeks of ineffective antidepressant therapy is commonly deemed unacceptable, and strategies designed to augment the response are being sought. Early studies assessing T3 effectiveness in augmenting the antidepressant response were neither placebo controlled nor focused on patient populations that could be directly compared. The first placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study reported results in 16 unipolar depressed outpatients who had experienced no improvement in their clinical outcomes with TCAs alone. The intervention consisted of adding 25 μg of T3 or placebo daily for 2 weeks before the patients were crossed over to the opposite treatment for an additional 2 weeks. No beneficial effect of T3 was apparent. The only other placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind trial investigating this question involved 33 patients with unipolar depression treated with either desipramine or imipramine for 5 weeks before random assignment to placebo or 37.5 μg of T3 daily. After 2 weeks of observation on T3, during which TCA levels were monitored, significantly more patients treated with T3 (10 of 17; 59%) had a positive response than did placebo-treated patients (3 of 16; 19%). A subsequent open clinical trial of imipramine-resistant depression, using a prolonged TCA treatment period preceding the addition of T3, showed no demonstrable T3 effect.

24. What evidence is there that the effect of SSRIs and ECT may be enhanced by the addition of T3?

The SSRI group of substances (including fluoxetine and sertraline) is the preferred antidepressant treatment in the United States today. A large, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to determine the role of T3 as augmentation therapy did not demonstrate an effect of T3 in augmenting the response of paroxetine (an SSRI) therapy in patients with major depressive disorder, but a similar study using sertraline and T3 showed a conflicting positive response. Responders in the Cooper-Kazaz report seemed to have had lower circulating thyroid hormone levels before treatment and to have experienced greater decreases in TSH levels as a result of the intervention. This finding may indicate that patients benefiting from the addition of T3 may have been subtly hypothyroid, and the addition of T3 compensated for this deficiency. A metaanalysis of the available data suggests that coadministration of T3 and SSRIs has no significant clinical effect in depressed patients when compared with SSRIs alone. More research is necessary to determine whether those patients with a functional type 1 deiodinase (D1) gene polymorphism may be more responsive to T3 cotreatment.

T3 has been reported to augment the antidepressant effect of ECT. However, there is little to no evidence to guide the duration of treatment with T3, and there are few studies on the side effects of long-term administration.

25. Are any psychiatric conditions recognized to respond to pharmacologic doses of T4?

For the 10% to 15% of patients with bipolar disorder with four or more episodes of manic-depressive psychosis yearly (rapid cyclers), the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease may reach 50% or higher. Therapeutic intervention with standard therapy such as lithium is frequently disappointing. Open-label studies treating such patients with T4 in pharmacologic doses sufficient to suppress serum TSH and elevate T4 levels to approximately 150% of normal showed that treatment may decrease the manic and depressive phases in both amplitude and frequency, and it led to remission in some patients. Given these encouraging results, controlled studies on the efficacy of T4 or T3 seem warranted.

26. Are mechanisms of thyroid hormone action on the brain known?

Thyroid hormones play a critical role in the development and function of the CNS. T3 receptors are widely distributed throughout the brain, and there is much evidence that thyroid hormone regulates brain function through interaction with the catecholaminergic system. Thyroid hormone action in brain tissue is accomplished through the binding of T3 to its nuclear receptor. The T3 is derived from T4 by the action of D2, which is located throughout the CNS.

27. Should T4 or T3 be used in treating the depressed patient?

Most studies using thyroid hormone as adjuvant therapy have used T3 rather than T4. In those reports assessing the advantages of one over the other, T3 was considered superior. In a randomized trial combining T4 or T3 with antidepressants, only 4 of 21 patients (19%) treated with 150 μg/day of T4 for 3 weeks responded, whereas 9 of 17 (53%) responded with 37.5 μg/day of T3. Further studies of open T4 treatment in antidepressant-resistant patients have appeared, but the lack of controls makes outcome interpretation difficult. One of these studies indicated that responders to T4 had significantly lower pretreatment serum T4 and reverse T3 levels, a finding leading the investigators to believe that the responders may have been subclinically hypothyroid. Adjuvant therapy with T4 rather than T3 may be indicated when subclinical hypothyroidism or rapid cycling bipolar disease is present. Because T4 equilibrates in tissues more slowly than T3, treatment with T4 for at least 6 to 8 weeks, and preferably longer, would be necessary to determine its efficacy in this situation.

As personalized medicine evolves, therapies will inevitably become more directed. Research directed at type 1 deiodinase (D1), which is important for serum conversion of T4 to T3, suggests that certain polymorphisms of D1 may be associated with a positive response to T3 potentiation of SSRIs. These patients with certain alleles have inherently lower D1 activity and therefore have naturally lower serum T3 levels. When compared with placebo, these patients have decreased depression scores at 8 weeks with T3 supplementation in combination with sertraline.

Conversely, there is evidence that specific subsets of patients may not respond to T3 potentiation. Genetic researchers have identified an organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) that is thought to be key in delivery of T4 to the brain. Polymorphisms in the OATP1C1 gene appear to be linked to increased depressive symptoms among patients with hypothyroidism. These patients do not appear to have any decrease in depressive scores with T3 supplementation when compared with controls. The clinical significance of these findings is yet to be determined, but it may have a meaningful impact on the future of depressive treatment.

28. Describe the proposed mechanisms linking thyroid function and depression.

It has been postulated that D2 activity in the CNS is deficient in depression, thereby giving rise to a state of brain hypothyroidism coexisting with systemic euthyroidism. Alternatively, D2 activity may be depressed by the elevated cortisol levels seen in depression and stress, thus resulting in T4 instead being converted to reverse T3 (rT3) by “inner ring” brain 5 deiodinase (type III deiodinase [5D-III]) activity, with decreased T3 and increased rT3 levels. Notably, T3 treatment is feasible because T3 is not dependent on transport by transthyretin, which is low in depression, and therefore would ensure adequate T3 delivery across the blood-brain barrier to the brain.

29. Do antidepressant medications have a mechanistic connection to the action of thyroid hormone in the brain?

It has been shown that desipramine, a TCA, and fluoxetine, an SSRI, both enhance D2 activity in the CNS, thus presumably increasing the availability of T3 in the brain. This could conceivably account for the clinical efficacy of these classes of drugs.

30. What recommendations can be made for the thyroid evaluation in psychiatric patients?

It seems prudent to check thyroid function test results in those psychiatric patients who are at increased risk for developing thyroid disease. Women more than 45 years of age, patients with known autoimmune diseases, individuals with a family history of thyroid disease, and those receiving lithium or suffering from dementia should be screened for underlying thyroid abnormalities. Patients receiving medications known to influence the interpretation of thyroid function tests should have these considered when interpreting the results of testing.

31. Who should receive thyroid hormone with the intent of relieving psychiatric symptoms?

It is recommended that T4 therapy be offered to any depressed patient with an elevated serum TSH, especially if it is accompanied by increased antithyroid antibody titers or a low free T4. Thyroid hormone replacement may alleviate the depression in these individuals. Conversely, antidepressant therapy, if required, may be ineffective before normalization of thyroid axis parameters. One observation suggests that there is a subset of patients with hypothyroidism who are taking T4 and who experience higher depression and anxiety scores than their euthyroid counterparts. These patients in particular, who may have D2 gene polymorphisms, may benefit from the addition of T3, but prospective trials have not yet been conducted. In patients with refractory depression but normal systemic thyroid function, adjuvant T3 therapy may not be worth considering.

Applehof, BC, et al. Triiodothyronine addition to paroxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6271–6276.

Asher, R. Myxoedematous madness. Br Med J. 1949;22:555–562.

Bauer, M, Whybrow, PC, Thyroid hormones and the central nervous system in affective illness. interactions that may have clinical significance. Integr Psychiatry 1988;6:75–100.

Bauer, M, et al. Effects of supraphysiological thyroxine administration in healthy controls and patients with depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:285–294.

Bell, RJ, et al, Well-being, health-related quality of life and cardiovascular disease risk profile in women with subclinical thyroid disease. a community-based study. Clin Endocrinol 2007;66:548–556.

Bocchetta, A, Loviselli, A. Lithium treatment and thyroid abnormalities. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:23.

Brent, GA, Larsen, PR, Treatment of hypothyroidism. Braverman LE, Utiger RD, eds. Werner and Ingbar’s the Thyroid. A Fundamental and Clinical Text. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2000;853–860.

Bunevicius, R, et al. Effects of thyroxine as compared with thyroxine plus triiodothyronine in patients with hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:424–429.

Chopra, IJ, Solomon, DH, Huang, TS, Serum thyrotropin in hospitalized psychiatric patients. evidence for hyperthyrotropinemia as measured by ultrasensitive thyrotropin assay. Metabolism 1990;93:538–543.

Cooper, DS, et al, l-Thyroxine therapy in subclinical hypothyroidism. a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:18–24.

Cooper-Kazaz, R, Lerer, B. Efficacy and safety of triiodothyronine supplementation in patients with major depressive disorder treated with specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:685–699.

Cooper-Kazaz, R, et al, Combined treatment with sertraline and liothyronine in major depression. a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:679–688.

Cooper-Kazaz, R, et al. Preliminary evidence that a functional polymorphism in type 1 deiodinase is associated with enhanced potentiation of the antidepressant effect of sertraline by triiodothyronine. J Affect Disord. 2009;116:113–116.

de Carvalho, GA, et al. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on thyroid function in depressed patients with primary hypothyroidism or normal thyroid function. Thyroid. 2009;19:691–697.

Demartini, B, et al. Prevalence of depression in patients affected by subclinical hypothyroidism. Panminerva Med. 2010;52:277–282.

Eker, SS, et al. Reversible escitalopram-induced hypothyroidism. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:559, e5–7.

Fava, M, et al. Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism in major depression revisited. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56:186–192.

Fliers, E, et al, Efficacy of triiodothyronine (T3) addition to paroxetine in major depressive disorder. a randomized clinical trial In Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society. Philadelphia: The Endocrine Society; 2003;S12–S19.

Gharib, H, et al, Consensus statement. subclinical thyroid dysfunction. A joint statement on Management from the American Association of Clinical Endcrinologists, the American Thyroid Association, and the Endocrine Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:581–585.

Grozinsky-Glasberg, S, et al, Thyroxine-triiodothyronine combination therapy versus thyroxine monotherapy for clinical hypothyroidism. meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2592–2599.

Gulseren, S, et al. Depression, anxiety, health-related quality of life, and disability in patients with overt and subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:133–139.

Hage, MP, Azar, ST. The link between thyroid function and depression. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:590–648.

Hein, MD, Jackson, IMD. Thyroid function in psychiatric illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1990;12:232–244.

Hennessey, JV, Jackson, IMD. The interface between thyroid hormones and psychiatry. Endocrinologist. 1996;6:214–223.

Jackson, IMD, Whybrow, PC. The relationship between psychiatric disorders and thyroid function. Thyroid Update,. 1995;9:1–7.

Jackson, IMD. The thyroid axis and depression. Thyroid. 1998;8:951–956.

Joffe, RT. Is the thyroid still important in major depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:367–368.

Jorde, R, et al. Neuropsychological function and symptoms in subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:145–153.

Monzani, F, et al, Subclinical hypothyroidism. neuro-behavioral features and beneficial effect of l-thyroxine treatment. Clin Invest 1993;71:367–371.

Murray, GR. Note on the treatment of myxoedema by hypodermic injections of an extract of the thyroid gland of a sheep. Br Med J. 1891;2:796–797.

Nelson, JC. Augmentation stategies in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 1):13–19.

Panicker, V, et al, A paradoxical difference in relationship between anxiety, depression and thyroid function in subjects on and not on T4. findings from the HUNT study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:574–580.

Panicker, V, et al. Common variation in the DIO2 gene predicts baseline psychological well-being and response to combination thyroxine plus triiodothyronine therapy in hypothyroid patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1623–1629.

Papakostas, GI, et al, Simultaneous initiation (coinitiation) of pharmacotherapy with triiodothyronine and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for major depressive disorder. a quantitative synthesis of double-blind studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;24:19–25.

Pardridge, WM, Carrier medicated transport of thyroid hormones through the rat blood-brain barrier. primary role of albumin bound hormone. Endocrinology 1979;105:605–612.

Parle, J, et al, A randomized controlled trial of the effect of thyroxine replacement on cognitive function in community-living elderly subjects with subclinical hypothyroidism. the Birmingham Elderly Thyroid study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:3623–3632.

Pollock, MA, et al, Thyroxine treatment in patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism but thyroid function tests within the reference range. randomized double blind placebo controlled crossover trial. Br Med J 2001;323:891–895.

Razvi, S, IL, Keeka, G, Oates, C, McMillan, C, Weaver, JU, The beneficial effect of l-thyroxine on cardiovascular risk factors, endothelial function, and quality of life in subclinical hypothyroidism. randomized, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1715–1723.

Report on myxoedema. Transactions of the Clinical Society of London; 1888.

Sachs, BA, Wolfman, L, Murthy, G, Lipid and clinical response to a new thyroid hormone combination. Am J Med Sci 1968;256:232–238.

Samuels, MH, et al. Health status, mood, and cognition in experimentally induced subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2545–2551.

Saravanan, P, et al, Psychological well-being in patients on “adequate” doses of l-thyroxine. results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clin Endocrinol 2002;57:577–585.

Sarne, D, DeGroot, LJ. Effects of the environment, chemicals and drugs on thyroid function. Endocrine Education. www.thyroidmanager.org, 2012.

Sawka, AM, et al. Does a combination regimen of thyroxine (T4) and 3,5,3’-triiodothyronine improve depressive symptoms better than T4 alone in patients with hypothyroidism? Results of a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4551–4555.

Selenkow, HA, Wool, MS. A new synthetic thyroid hormone combination for clinical therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1967;67:90–99.

Smith, RN, Taylor, SA, Massey, JC. Controlled clinical trial of combined triiodothyronine and thyroxine in the treatment of hypothyroidism. Br Med J. 1970;4:145–148.

Taylor, S, Kapur, M, Adie, R. Combined thyroxine and triiodothyronine for thyroid replacement therapy. Br Med J. 1970;2:270–271.

Tremont, G, RA, S. Use of thyroid hormone to diminish the cognitive side effects of psychiatric treatment. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:273–280.

van der Deure, WM, et al. Polymorphisms in the brain-specific thyroid hormone transporter OATP1C1 are associated with fatigue and depression in hypothyroid patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69:804–811.

Vigario, P, et al. Perceived health status of women with overt and subclinical hypothyroidism. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18:317–322.

Walsh, JP, et al, Combined thyroxine/liothyronine treatment does not improve well-being, quality of life, or cognitive function compared to thyroxine alone. a randomized controlled trial in patients with primary hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:4543–4550.

Whybrow, PC. The therapeutic use of triiodothyronine and high dose thyroxine in psychiatric disorders. Acta Med Aust. 1994;21:47–52.