Chapter 597 Pseudotumor Cerebri

Etiology

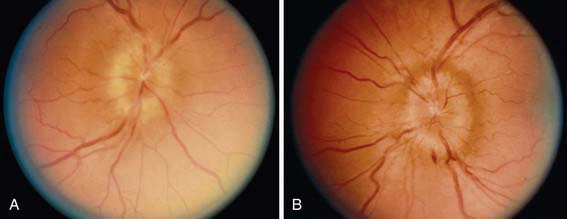

Table 597-1 lists the many causes of pseudotumor cerebri. There are many explanations for the development of pseudotumor cerebri, including alterations in CSF absorption and production, cerebral edema, abnormalities in vasomotor control and cerebral blood flow, and venous obstruction. The causes of pseudotumor are numerous and include metabolic disorders (galactosemia, hypoparathyroidism, pseudohypoparathyroidism, hypophosphatasia, prolonged corticosteroid therapy or rapid corticosteroid withdrawal, possibly growth hormone treatment, refeeding of a significantly malnourished child, hypervitaminosis A, severe vitamin A deficiency, Addison disease, obesity, menarche, oral contraceptives, and pregnancy), infections (roseola infantum, sinusitis, chronic otitis media and mastoiditis, Guillain-Barré syndrome), drugs (nalidixic acid, doxycycline, minocycline, tetracycline, nitrofurantoin), isotretinoin used for acne therapy especially when combined with tetracycline, hematologic disorders (polycythemia, hemolytic and iron-deficiency anemias [Fig. 597-1], Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome), obstruction of intracranial drainage by venous thrombosis (lateral sinus or posterior sagittal sinus thrombosis), head injury, and obstruction of the superior vena cava. When a cause is not identified, the condition is classified as idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Table 597-1 ETIOLOGY OF CHILDHOOD PSEUDOTUMOR CEREBRI

HEMATOLOGIC

INFECTIONS

DRUGS

RENAL

NUTRITIONAL

CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISORDERS

ENDOCRINE

OTHER

POSSIBLE ASSOCIATIONS

Abu-Serieh B, Ghassempour K, Duprez T, et al. Stereotactic ventriculoperitoneal shunting for refractory idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(6):1039-1043.

Acheson JF. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and visual function. Br Med Bull. 2006;79–80:233-244.

Bruce BB, Preechawat P, Newman NJ, et al. Racial differences in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2008;70(11):861-867.

Dirge KB. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. BMJ. 2010;341:109-110.

Distelmaier F, Sengler U, Messing-Juenger M, et al. Pseudotumor cerebri as an important differential diagnosis of papilledema in children. Brain Dev. 2006;28(3):190-195.

Friedman DI. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11(1):62-99.

Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri. Neurol Clin. 2004;22(1):99-131.

Goyal S, Krishnamoorthy K, Noviski N, et al. What’s new in childhood idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neuroophthalmology. 2009;33:23-35.

Kesler A, Bassan H. Pseudotumor cerebri—idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the pediatric population. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006;3(4):387-392.

Matthews YY. Drugs used in childhood idiopathic or benign intracranial hypertension. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93(1):19-25.

Mercille G, Ospina LH. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a review. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28(11):e77-86.

Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):597-617.

Thuente DD, Buckley EG. Pediatric optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(4):724-727.