CHAPTER 150 Pseudotumor Cerebri

Terminology

The syndrome known as pseudotumor cerebri (PTC) is generally thought of as a condition characterized by increased intracranial pressure (ICP) without evidence of dilated ventricles or a mass lesion by imaging, normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) content, and papilledema occurring in most cases (but not all—see later) in young, obese women without any clear explanation. The terminology used to describe this condition has changed dramatically over time and continues to change as new issues regarding its etiology are raised. The condition was probably first described by Quincke in 18971; however, the term pseudotumor cerebri appears to have first been used in 1914.2 Subsequently, Foley suggested calling the condition “benign intracranial hypertension” because it appeared to have a much more benign neurological prognosis than increased ICP caused by a central nervous system mass lesion or infection.3 Because significant visual morbidity may result from PTC, use of the adjective “benign” is no longer considered appropriate terminology. Instead, most physicians use the term idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) for cases of PTC that occur in young, obese patients and the term secondary pseudotumor cerebri for the rare cases in which a cause (e.g., drug induced) is identified.4,5 The problem with this terminology is that a substantial percentage of patients with so-called IIH have been shown to have some degree of lateral sinus stenosis. At issue is whether the stenosis is the cause or the effect of the increased ICP. If one believes—as many do—that the stenosis is the cause of the condition, patients previously considered to have IIH but who exhibit lateral sinus stenosis may have to be put into the category of secondary PTC, even though they are otherwise identical in body habitus, age, and other features as patients without lateral sinus stenosis. This issue is discussed in more detail later. It suffices here simply to state that (1) one should not use the term pseudotumor cerebri synonymously with idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and (2) some patients previously thought to have IIH because no cause could be identified may now be considered to have a condition caused by stenosis of one or both lateral sinuses. In this chapter I use the terms pseudotumor cerebri to describe the general condition and idiopathic intracranial hypertension when discussing the condition formerly thought to have no identifiable cause but, in some cases, appears to be associated with lateral sinus stenosis. It should also be emphasized that some authors use the term pseudotumor syndrome for patients with increased ICP unassociated with ventricular dilation, evidence of cerebral edema, or an intracranial mass lesion but with abnormal CSF content. This condition occurs in some patients with aseptic, carcinomatous, or lymphomatous meningitis. This chapter deals only with patients who have true PTC, not this “pseudotumor syndrome.”

Epidemiology

PTC affects infants, children, and young adults. The idiopathic form (i.e., IIH), which represents about 90% of cases, is typically a disorder of obese females of childbearing age,5 but it may also occur in men and young children.6 The incidence of IIH varies throughout the world. Two studies in the United States estimated the incidence to be approximately 0.9 per 100,000 in the general population with a female-to-male ratio of 8 : 1.7,8 The incidence increases to 3.5 per 100,000 in women aged 20 to 44 years and further increases to 13 per 100,000 in women who are 10% over ideal weight and 19 per 100,000 in women who are 20% over ideal weight.7 A recent and rapid gain in weight is associated with an increased risk for IIH in both obese and nonobese patients.9,10 All races are affected, and there is evidence that African Americans have a worse prognosis than white individuals regardless of treatment.11 Secondary PTC, which accounts for about 10% of cases, may develop at any age and occurs with equal frequency in both sexes.

Symptoms and Signs

Primary PTC (i.e., IIH) and secondary PTC produce identical symptoms and signs. Occasionally, the condition is asymptomatic and discovered during a routine ophthalmic examination when papilledema is found12; however, the most common symptom, as well as most often the initial symptom, is headache, which occurs in approximately 90% of cases.4,5 The character of the headache is not specific, but it is generally different from previous headaches and is severe.13–15 It most frequently is bifrontal or generalized, pressure-like, and often associated with neck pain.13 The headache usually occurs daily but may be intermittent. Many patients have migrainous features, including unilateral pain, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia.15 It may awaken the patient from sleep or resemble a “brain tumor headache” that is worse in the morning and aggravated when cerebral venous pressure is increased by Valsalva maneuvers (e.g., coughing, sneezing).

The second most common symptom of PTC is transient visual loss. Typical transient obscurations of vision (TOVs) are reported by about 70% of patients.4,5 They may be unilateral or bilateral and generally last only a few seconds. They are thus quite different from the TOVs experienced by patients with carotid artery or cardiac valvular disease, which typically last at least 15 minutes. The TOVs occurring in patients with PTC are often precipitated by a change in posture (e.g., bending over, arising from a stooped position) or rolling the eyes. In some patients, TOVs occur 20 to 30 times a day. The visual loss may be partial or complete. TOVs indicate the presence of optic disc swelling, usually severe, but are not a sign of a poor prognosis. They probably reflect transient ischemia of the optic disc caused by the papilledema.

A small percentage of patients with PTC complain of visual loss that may be characterized as an enlarged dark spot in the temporal visual field. This is caused by enlargement of the physiologic blind spot as a result of severe papilledema. Tunnel vision and central visual loss may occur in more chronic cases13 or acutely from ischemic optic neuropathy.16 The visual loss in patients with PTC may also arise from local associated ocular causes, such as macular hemorrhage, exudates, or accumulation of subretinal fluid.17,18

Diplopia, reported by approximately 40% of patients, is usually horizontal and results from unilateral or bilateral abducens nerve paresis, a nonlocalizing feature of increased ICP.4,5 Rarely, there is vertical diplopia from trochlear nerve paresis, oculomotor nerve paresis, or skew deviation.19

Pulsatile tinnitus is not uncommon in patients with PTC, although such patients rarely mention this symptom unless asked directly about it. Frequently described as a whooshing sound, hearing a heartbeat in the head, or a high-pitched noise, pulsatile tinnitus is thought to reflect flow disturbances within the cerebral venous system.13,20 It may be unilateral or bilateral and is often more prominent at night or in quiet surroundings.

Focal neurological deficits in patients with PTC are extremely uncommon, and their occurrence should make one consider alternative diagnoses21; however, patients with chronic PTC are more likely to be anxious or depressed or feel that they have a worse quality of life than age-matched control subjects.9,10,22 Cognitive deficits are less well substantiated and may be a manifestation of headache-related concentration difficulties, depression, or anxiety.22

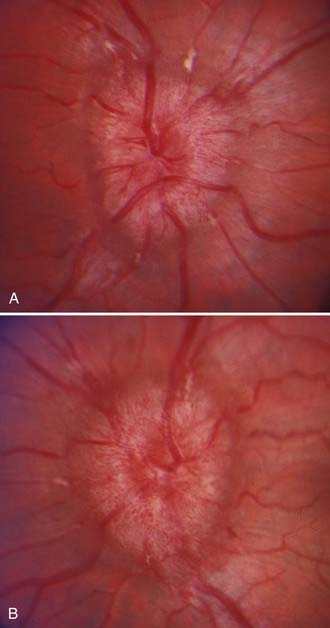

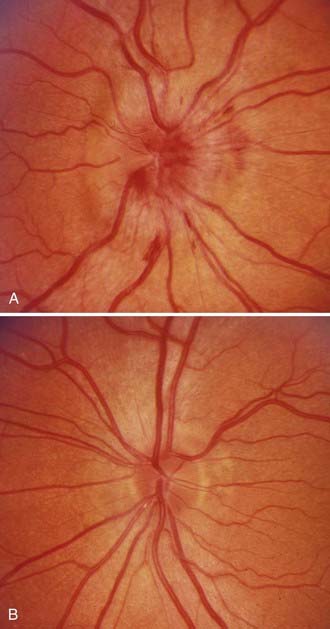

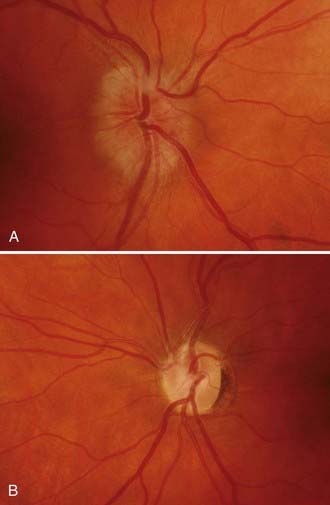

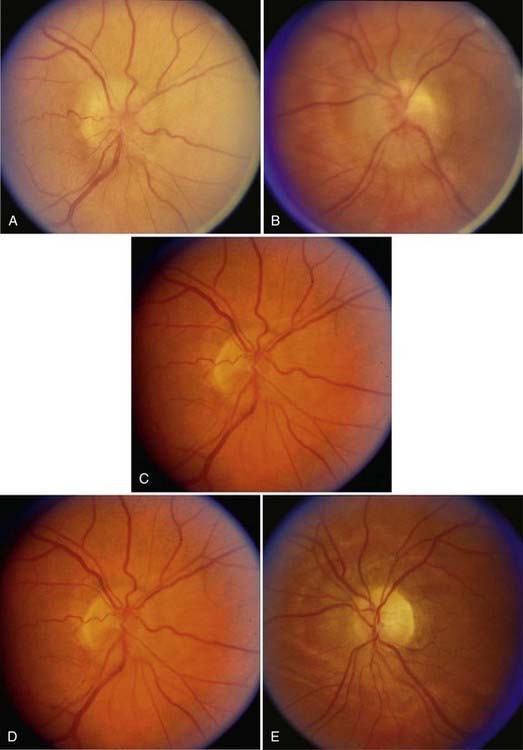

Papilledema is the diagnostic hallmark of PTC and is present in almost all patients.4,5 The papilledema of PTC is identical with that in patients with other causes of increased ICP. It is almost always bilateral and symmetrical (Fig. 150-1), but it may be asymmetric or, occasionally, unilateral (Fig. 150-2).23 Several grading systems for papilledema have been proposed over the years. The system most commonly used is the Frisén system, which separates the appearance of the optic disc into stages ranging from normal appearance (stage 0) to very severe papilledema (stage 5) (Table 150-1 and Fig. 150-3).24 The importance of this grading system cannot be overemphasized because it—along with color vision assessment and visual field testing—is crucial in determining the appropriate management of any patient with papilledema, particularly a patient with PTC. It should also be noted that PTC may occur without papilledema, but it is uncommon and the diagnosis should be made with caution in such a setting, preferably only after continuous CSF pressure monitoring.25

| Stage 0—Normal Optic Disc |

From Frisén L. Swelling of the optic nerve head: a staging scheme. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982;45:13-18.

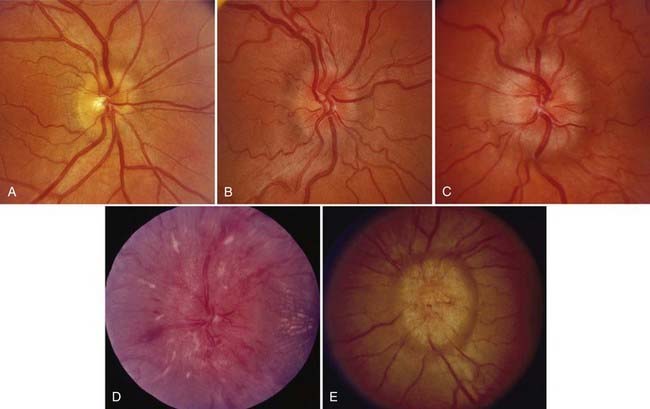

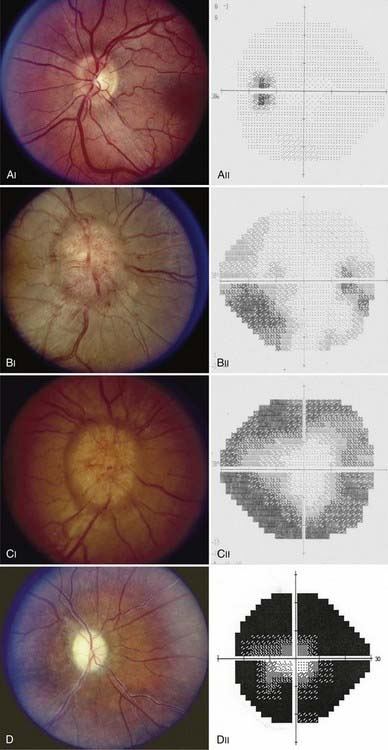

As with papilledema from other causes, loss of central visual acuity is uncommon in patients with PTC unless they have sustained severe damage to the optic nerves or there is an intraocular cause, such as macular hemorrhage or exudates, all of which should be easily visible with an ophthalmoscope. Instead, the visual dysfunction usually begins with visual field defects similar to those that occur in patients with glaucoma (Fig. 150-4). Thus, loss of central acuity in a patient with PTC who has severe papilledema and no evidence of an intraocular cause for the loss of vision indicates an advanced process, requires immediate and aggressive treatment, and confers a poor prognosis for recovery, even if urgent therapy is undertaken immediately.

FIGURE 150-4 A-E, Progression of visual field defects in papilledema with corresponding appearance of the optic disc.

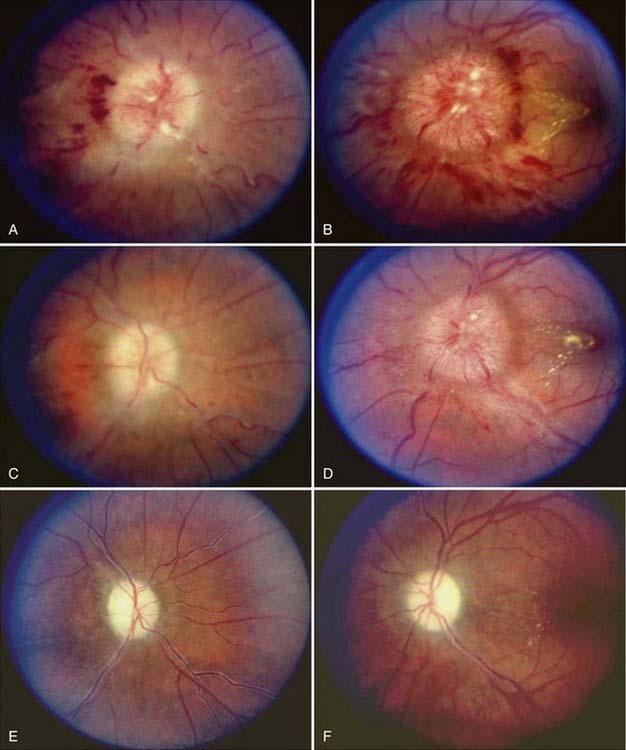

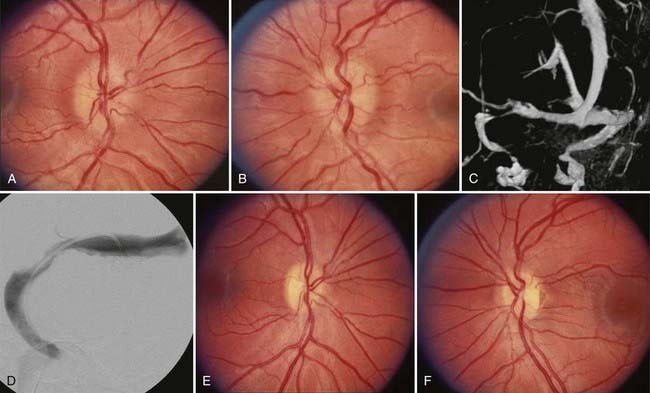

Postpapilledema optic atrophy occurs in untreated or inadequately treated patients after a variable period, usually several months, but occasionally within weeks of the onset of symptoms (Fig. 150-5). Some patients have persistent chronic papilledema without visual deterioration or optic atrophy. Postpapilledema optic atrophy in patients with PTC usually develops symmetrically, but just as papilledema may be asymmetric, so postpapilledema optic atrophy can be asymmetric. In some patients a pseudo–Foster Kennedy syndrome develops that is characterized by postpapilledema optic atrophy in one eye and papilledema in the other (Fig. 150-6).26

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of both IIH and secondary PTC requires that there be no intracranial or spinal mass, no evidence of hydrocephalus, documented increased ICP, and normal CSF contents.4,5 Thus, the diagnosis cannot and should not be made without neuroimaging and a lumbar puncture (LP).

Neuroimaging

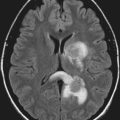

The rationale for neuroimaging studies in patients with suspected PTC is twofold: first, to exclude a condition such as a tumor producing hydrocephalus or a mass effect that would put the patient at risk for herniation and, second, to ensure that there is no secondary cause of the increased ICP. Although computed tomography (CT) is generally adequate to ensure that the patient will not be at risk when undergoing LP, the resolution of this study is insufficient to exclude certain posterior fossa lesions, isodense lesions not associated with ventriculomegaly, gliomatosis cerebri, meningeal abnormalities, or venous sinus thrombosis.27 Thus, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended for most patients.4,5 For children, men, and non-overweight women or patients with symptoms or signs that are atypical for PTC, MR or CT venography should be performed. Indeed, even patients who appear to have the typical clinical picture of IIH may show evidence of venous sinus thrombosis on MR venography.28 Catheter-based angiography with venous-phase sequences may also be needed in such patients if venous sinus thrombosis is suspected and the results of noninvasive venography are equivocal. In addition, I and others have seen patients with apparent IIH who initially had no evidence of venous sinus thrombosis but who then worsened and underwent repeat imaging that subsequently showed venous sinus thrombosis.29

The diagnosis of PTC should not be made in patients with an intracranial or spinal mass lesion; however, about 50% of patients with the condition have an empty sella as a result of the chronically increased ICP. In addition, a small percentage of patients with PTC have a Chiari type I malformation or cerebellar ectopia.30 In some cases, this results from downward pressure on the cerebellar tonsils; however, in other cases, it is thought that the Chiari malformation is the cause rather than the effect of the increased ICP, and in such cases, treatment is directed at the malformation (see later). Finally, as noted earlier, an increasing percentage of patients who in the past would be considered to have IIH are being shown to have unilateral or, occasionally, bilateral lateral sinus stenosis.

Examination of Cerebrospinal Fluid

Examination of CSF is required for the diagnosis of PTC to confirm an elevated opening pressure and to exclude a malignant, infectious, or inflammatory process that might simulate PTC. Normal lumbar CSF pressure in both obese and nonobese adults is 200 to 250 mm H2O, and thus values between 201 and 249 are nondiagnostic.31,32 Consequently, the diagnosis of PTC cannot be made unless the CSF opening pressure is 250 mm H2O or greater. In prepubertal children, a value higher than 200 mm H2O is probably abnormal. Because CSF pressure normally fluctuates, multiple CSF pressure measurements or prolonged CSF pressure monitoring is sometimes required, depending on the clinical circumstance.33 In obese patients, LP may be technically challenging to perform, in which case fluoroscopic guidance is extremely helpful. To ensure accuracy, lumbar CSF pressure must be measured with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, relaxed with the legs partially extended. The pressure may be artifactually elevated if the patient is crying, performing a Valsalva maneuver, or in severe pain.34 CSF should be analyzed for glucose and protein concentration, presence of cells, cytology, and atypical infections (e.g., syphilis, Cryptococcus, fungus). A diagnosis of PTC should not be made unless the CSF contents are completely normal.4,5

Secondary Pseudotumor Cerebri

IIH is a diagnosis of exclusion that occurs primarily in young obese women and, occasionally, in obese men with no evidence of any underlying disease4,5,35,36; however, about 10% of cases of PTC are associated with a number of different conditions. Suspicion of a secondary cause of PTC is heightened in prepubertal children, men, nonobese women, and otherwise typical patients with rapidly progressive visual loss that does not respond to treatment. Secondary causes of PTC include (1) impairment or obstruction of cerebral venous sinus drainage by intrinsic or extrinsic lesions, (2) endocrine and metabolic dysfunction, (3) exposure to exogenous drugs and other substances, (4) withdrawal of certain drugs, and (5) systemic illnesses.4,5,35,36 It is important to realize that although many conditions have been reported to be associated with PTC, relatively few are likely to be true associations. Tables 150-2 to 150-5 list the best substantiated and most frequently observed ones.

TABLE 150-2 Causes of Obstruction/Impairment of Cerebral Venous Drainage Associated with Secondary Pseudotumor Cerebri

| Obstruction of the Superior Sagittal Sinus |

TABLE 150-3 Endocrine and Metabolic Disturbances Associated with Pseudotumor Cerebri

TABLE 150-4 Exogenous Substances Whose Exposure, Ingestion, or Withdrawal Has Been Associated with Pseudotumor Cerebri

TABLE 150-5 Systemic Illnesses Associated with Pseudotumor Cerebri

Complications

The natural history of PTC is variable. In some cases it is a self-limited condition; in others, ICP remains elevated for many years, even if the systemic and visual symptoms resolve. In still other patients, the condition resolves but then recurs months to years later or a stable condition suddenly worsens.37 The most feared complication of PTC is permanent visual loss. In one long-term study performed before the era of modern neuroimaging, 57 patients with a diagnosis of PTC were monitored for 5 to 41 years.38 Severe visual impairment occurred in one or both eyes in 14 patients (24.5%), and in 7 patients the visual loss occurred months to years after the initial symptoms appeared. In more than 80% of the patients in this study, CSF pressure remained elevated, regardless of the treatment that the patients had received. In a more recent prospective study of 50 patients treated for IIH, visual acuity was worse than 20/20 in 13%.13 The effects of even self-limited PTC on the visual system may be catastrophic. PTC produces significant visual impairment in approximately 25% of patients and permanent visual field abnormalities in most patients.4,5,13

Pathophysiology

Although the mechanism by which ICP is increased may be clear in some cases of secondary PTC, the reason that the ventricles do not dilate is not. Furthermore, even the mechanism by which ICP becomes increased may be unclear, not only in cases of IIH but also in cases of secondary PTC such as those that are drug induced. There is certainly no evidence of brain edema by either standard MRI or diffusion tensor imaging.39,40 Similarly, assessment of the plasma levels of ghrelin—a hormone that appears to be involved in the regulation of body weight—found no difference between obese patients with and without evidence of IIH.41 Most evidence points to decreased absorption of CSF with increased cerebral blood volume; however, despite the progress in our understanding of IIH, Fishman’s comment that there are “more speculations than data available” remains applicable.42

Monitoring

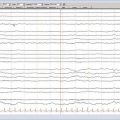

Progressive loss of visual function most often develops in patients with PTC in a manner similar to that occurring in patients with chronic open-angle glaucoma in that field defects are usually the first manifestation, followed by progressive visual field constriction, color vision loss, and finally, loss of central vision.4,5 Thus, once patients complain of reduced visual acuity or “tunnel vision,” they are, as noted earlier, in need of rapid, aggressive intervention because they have advanced disease that will result in permanent visual dysfunction if not treated immediately and that may remain permanent even if treatment is initiated immediately. In addition, the tempo of visual loss in patients with PTC may be rapid or slowly progressive.16 Conversely, most visual deficits associated with papilledema are reversible if ICP is lowered before severe visual loss or optic nerve ischemia develops.43,44 Thus, it is imperative that patients be monitored by an ophthalmologist who can assess the best-corrected visual acuity, color vision, visual fields by quantitative static or kinetic perimetry, and severity of papilledema so that appropriate and timely intervention can be performed before permanent visual dysfunction occurs. In addition to standard clinical testing, stereo color photographs of the optic discs obtained on a regular basis are helpful in providing the examiner with objective evidence of the appearance of the optic discs. Although some authors recommend monitoring patients with PTC with devices to measure the thickness of the peripapillary nerve fiber layer,45 we have not found such techniques to be particularly useful.

The intervals between clinical assessment of patients with PTC must be individualized. At disease onset, some patients require an evaluation every 1 to 2 weeks until a pattern of progression or stability is established. Other patients can be examined every 1 to 3 months without fear that they will lose vision in the interim, and patients with stable vision and mild or moderate papilledema may need to be examined only every 4 to 12 months. Most patients may be monitored clinically by following their visual status rather than by LP, and once it is established that the results of neuroimaging studies are normal, subsequent scans are not helpful in assessing the patient’s status. There is evidence that puberty is a risk factor for a less favorable visual outcome than that in prepubertal, teenage, or adult persons.46 There is also evidence that African Americans are more likely than white individuals to experience severe visual loss regardless of access to care, duration of symptoms, visual status at the time that treatment is begun, or the type of treatment11 and that severe visual loss is twice as likely to develop in men as in women.47 Thus, it would appear appropriate to monitor pubescent children, men, and all African American patients very closely and to initiate treatment earlier in the course of the disorder in these groups than in others.

Treatment

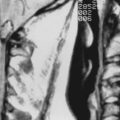

Regardless of the cause, the primary goals of treatment in patients with PTC are preservation of vision and alleviation of symptoms. Treatment of PTC in adults and children is similar. In asymptomatic patients with mild papilledema, close observation without specific therapy may be undertaken once an underlying cause is excluded. If a secondary cause is identified, it should be treated appropriately. For example, implicated exogenous agents should be discontinued, obstructive sleep apnea treated, and Chiari malformations decompressed (Fig. 150-7).48,49 Although treating the underlying condition usually produces improvement, it may also be necessary to use other medical and surgical treatments specifically directed at controlling ICP, at least as temporizing measures.

Treatment Related to Obesity

For patients with IIH associated with obesity, weight loss is advised, particularly since several retrospective studies have indicated that a modest degree of weight loss (6% to 10% of body weight) results in complete or at least more rapid resolution of the condition.50,51 When possible, the weight loss should be achieved through a combination of diet and exercise prescribed by a registered dietician or nutritionist who can assist the patient in setting realistic goals. Many obese women with IIH also have orthostatic edema and excessive sodium or water retention.52 In such patients, decreasing food intake while increasing water consumption, as is commonly used in weight reduction plans, may be counterproductive, and sodium restriction is often helpful. When weight loss efforts fail, bariatric surgery may be considered. Such surgery is generally successful in producing weight reduction, resolution of papilledema, and return of ICP to normal53,54; however, significant complications may occur, including anastomotic leaks, small bowel obstruction, malabsorption syndromes, Wernicke’s encephalopathy, and gastrointestinal bleeding.53,55 It must be emphasized that weight reduction should not be used as the only treatment in patients with PTC who have acute visual loss or severe papilledema with significant visual field loss. It is, however, reasonable as the only treatment for patients with mild PTC, no evidence of optic neuropathy and little or no headache, and as long-term management of the condition.

Medical Treatment

Medications to Reduce Headache

Many medications may be helpful for patients in whom headache is the main problem, although some of these medications have the potential to cause weight gain (e.g., sodium valproate, tricyclic antidepressants) or fluid retention (e.g., calcium channel blockers). Early experience with topiramate has been promising. It effectively prevents or reduces headaches, has mild carbonic anhydrase activity, and commonly produces weight appetite,56–59 although it has a number of potential side effects, including angle-closure glaucoma.57,60

Many patients with PTC experience headaches that are unrelated to their ICP.61 We discourage the frequent use of analgesics in such patients because of the potential development of analgesic-induced headaches, which may be extremely difficult to treat.

Medications to Lower Intracranial Pressure

Carbonic anhydrase, present in the choroid plexus, has a major role in the secretion of CSF. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors decrease the production of CSF and thereby result in decreased sodium ion transport across the choroidal epithelium.62 They also have a mild diuretic effect. Although as noted earlier topiramate has been suggested as an ideal drug for PTC because of its ability to decrease the production of carbonic anhydrase while also decreasing headache and reducing appetite,56–59 the most commonly used agent is acetazolamide (Diamox).4,5,58 Reduced ICP may be observed in patients with idiopathic PTC within several hours after intravenous administration and within hours to days after oral administration of acetazolamide.58,63 In adults, acetazolamide is generally begun at a dose of 1 g/day given in divided doses of either 250 mg four times a day or 500-mg Sequels twice a day. Lower doses usually have no effect and should not be considered. Theoretically, the dose of acetazolamide can be increased up to a maximum of 4 g/day, but the maximum dose is often limited by side effects, including paresthesias of the extremities, lethargy, and altered taste sensation.63 These side effects can be reduced but not eliminated by using Sequels, if available. Alternatively, methazolamide (Neptazane) may be used and is sometimes better tolerated than acetazolamide.

Diuretics such as furosemide and chlorthalidone are sometimes used to treat PTC.52,64 In general, they are not as effective as either acetazolamide or topiramate. Spironolactone and triamterene may be considered in patients who are allergic to carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and other sulfonamide-containing diuretics. Combining diuretics or using them with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may induce hypokalemia and should be done with extreme caution.

Although systemic corticosteroids are clearly beneficial in the treatment of PTC associated with various systemic inflammatory disorders, such as sarcoidosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, they are not recommended for routine use in patients with PTC.4,5 Corticosteroids lower ICP acutely, but their withdrawal leads to a rebound increase in ICP. Moreover, their long-term side effects (weight gain, fluid retention) are undesirable in the population most commonly affected by IIH. Nevertheless, corticosteroids may be appropriate for the urgent treatment of patients with impending or progressive visual loss while awaiting a definitive surgical procedure.65,66

Surgical Procedures

Surgery is performed when patients initially have severe optic neuropathy or when other forms of treatment have failed to prevent visual loss. It is not recommended for the treatment of headaches alone. At one time, subtemporal decompression was the procedure of choice, but this has generally been replaced by various operations to divert CSF or by optic nerve sheath fenestration (ONSF).67 The decision whether to proceed with a CSF diversion procedure or ONSF depends largely on the local resources available. There is more information available regarding the risks and benefits of ONSF than shunts in patients with PTC.67,68 Thus, although one may argue that shunting treats the primary pathology of PTC,67 the risks and benefits of each procedure must be considered for each patient. Although it appears from one retrospective study that ventriculoatrial and ventriculoperitoneal shunts are more effective than ONSF in alleviating headache and just as effective in decreasing ICP and preserving or improving vision,69 most attempts at comparisons are confounded by differences in surgical technique and assessment of outcomes, the retrospective nature of the data, and underreporting of adverse events. In addition to shunt procedures and ONSF, attention has recently focused on the role of cerebral venous sinus stenting for the treatment of PTC in patients who have evidence of lateral or sigmoid sinus stenosis (see later).

Cerebrospinal Fluid Diversion Procedures

In the past, most neurosurgeons preferred to perform a lumboperitoneal shunt procedure for patients in whom surgery was thought to be warranted. The results are generally quite good with respect to visual preservation or improvement and resolution of headache67,70,71; however, these shunts often malfunction, with at least one revision required within a year after placement, and a Chiari malformation can develop in some patients, particularly children.70,72 Most of the malformations are asymptomatic or cause minor neurological manifestations, but fatal tonsillar herniation after lumboperitoneal shunting for PTC has been reported.73 Now that stereotactic devices are available for the placement of intracranial devices, many surgeons prefer to perform either a ventriculoperitoneal or a ventriculoatrial shunt procedure for PTC because both are quite effective in relieving headache and lowering ICP in patients with PTC and have less likelihood of failure.67,69,74,75 In the rare instance in which neither a lumbar nor a ventricular site is available, a shunt can be placed in the cisterna magna.76 Although this type of shunt results in reduction of ICP, it is associated with a high complication rate. Indeed, all shunt procedures may be complicated by a variety of problems, including spontaneous obstruction of the proximal or distal ends of the shunt, excessively low pressure, infection, and migration of the distal end of the catheter resulting in chest or abdominal pain.69–72

Optic Nerve Sheath Fenestration

ONSF (also called “optic nerve sheath decompression”) is a procedure in which the optic nerve just posterior to the globe is exposed and several slits or some other type of opening is made in the dura and arachnoid sheaths of the nerve to allow CSF to escape, thus decompressing the nerve. Both lateral and medial approaches are used, almost all of which incorporate an operating microscope.68,77–80

Successful ONSF results in resolution of papilledema on the operated side and occasionally on the other, with bilateral improvement in visual function in many cases.68,78,80 The procedure immediately reduces pressure on the nerve by creating a filtration site that controls the intradural pressure surrounding the orbital segment of the optic nerve.81 Although the procedure is usually quite effective in reducing pressure on the optic nerve and some patients report substantial improvement in headaches after ONSF, most studies show no effects of ONSF on ICP,82,83 and it is thought that the decrease in papilledema and the subsequent visual improvement or stabilization result from a local decrease in optic nerve sheath pressure rather than from a generalized decrease in ICP.82,83 In contrast, one study showed persistently decreased CSF pressure after ONSF as assessed by repeated LP for 3 years after the procedure.84 The mechanism of the long-term effectiveness of ONSF may be fibrous scar formation between the dura and optic nerve, thus creating a barrier that protects the proximal optic nerve from the effects of increased ICP.

The risks associated with ONSF, although low, are nevertheless significant. They include infection, transient or permanent diplopia, and transient or permanent loss of vision from central retinal artery occlusion or ischemic optic neuropathy.67,68 In addition, a substantial percentage of patients require repeated ONSF. Although a second procedure is technically much more difficult and never as effective as the first, most adults and children have stabilization or improvement of vision after ONSF.67,68,78,80

Venous Sinus Stenting

As noted earlier, it is clear that occlusion of the cerebral venous sinuses can produce increased ICP and papilledema; however, it was previously assumed that there was no role of venous disease in the etiology of PTC. Recently, several groups using ICP monitoring devices have documented high pressures in the venous sinuses in typical cases of PTC.85,86 These sometimes appear to be secondary to central venous hypertension, but they more often appear to be the result of focal stenotic lesions in the lateral sinuses obstructing cranial venous outflow.87,88 This has led an increasing number of investigators to suggest that undetected intracranial venous hypertension may, in fact, be the substrate for all cases of PTC,86 although others have argued that at least in some cases, the venous hypertension is the effect rather than the cause of elevated ICP because after removal of CSF, the apparent venous sinus stenosis may resolve.85,89,90 I agree with Corbett and Digre that considering venous hypertension as the cause of the elevated ICP in IIH does not explain why the condition has a disproportionate predilection for young women, why the few men in whom IIH develops are less likely than women to be obese, or why children in whom IIH develops are even less likely to be obese.91 In addition, I also agree that other conditions that result in increased venous pressure, such as various forms of cardiac disease, are not typically associated with IIH. Nevertheless, the concept of venous sinus stenosis as a cause of PTC has been strengthened by the results of several groups that have found persistence of lateral sinus stenosis after normalization of ICP in patients with presumed IIH.92 In addition, other groups have performed stenting in patients with PTC in whom the usual investigations failed to reveal a cause of the raised ICP but catheter venography showed an area of stenosis with a significant pressure gradient across it in one or both lateral sinuses, after which the majority have shown an immediate reduction in ICP to normal with resolution of papilledema and improvement in visual function (Fig. 150-8).93–96 As with other procedures, stenting is not without potential and occasionally fatal complications and, in my opinion, should be reserved for patients with clear-cut lateral sinus stenosis with evidence by manometry of a significant pressure gradient across the area of stenosis.

Special Circumstances

Pregnancy

Women in whom PTC develops during pregnancy are diagnosed and treated similarly to nonpregnant women. Most women do well, with little or no permanent visual loss.97,98 There is no contraindication to pregnancy in women with a history of PTC, and no special provisions are required for delivery unless other medical complications are present. Although acetazolamide in high doses may produce birth defects in animals, there is little clinical or experimental evidence to support any adverse effect of the drug on pregnancy outcomes in humans.99 Thus, if the clinical setting warrants, the drug can be offered after appropriate informed consent. Conversely, caloric restriction, thiazide diuretics, and tricyclic antidepressants are generally avoided. If a surgical procedure is required, I would prefer ONSF to a shunt procedure in which the distal end of the catheter is in the peritoneum because of the risk for shunt malfunction from obstruction of the peritoneal catheter as the uterus enlarges,97 although a ventriculoatrial shunt would still be a reasonable option. PTC arising in the postpartum period or after a spontaneous abortion should raise suspicion for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, even in women who are overweight or obese.100

Fulminant Pseudotumor Cerebri

A small subgroup of patients with PTC experience a rapid onset of symptoms and precipitous visual decline.16 They often have significant visual field loss, central visual acuity loss, and marked papilledema on initial examination. This setting requires rapid and aggressive treatment. A multidisciplinary physician team and one or more surgical procedures are usually required but may still be unsuccessful in preserving vision. In such cases, we favor insertion of a lumbar drain until a definitive shunt procedure or ONSF can be performed. In some cases, I will perform emergency ONSF and a shunt procedure at the same time. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is an important diagnostic consideration in these patients.

Prognosis

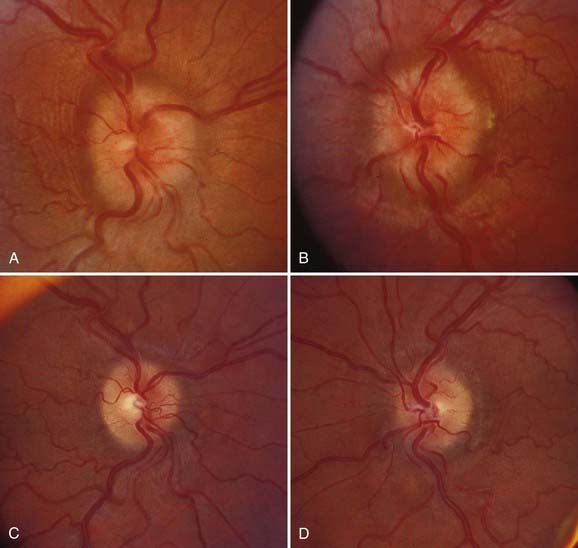

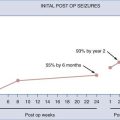

Most patients in whom the diagnosis of PTC or IIH is made before severe constriction of the visual field or loss of the central field has occurred and in whom appropriate treatment is initiated have an excellent visual prognosis (Fig. 150-9).5,43,44 In many of these cases, the visual field and sometimes visual acuity and color vision improve once ICP is lowered and the papilledema resolves. Indeed, even patients with severe papilledema associated with substantial visual field defects may experience improvement. Having said this, it is clear that the worse the visual function when treatment is begun, the less likely the patient is to experience visual improvement, and even patients in whom treatment appears to be initiated early in the course of the disorder may experience progressive visual loss. As noted earlier, this appears to particularly be the case in pubescent children,46 in men,47 and in African Americans11 and is not related, at least in African Americans, to access to care, duration of symptoms, visual status at the time of treatment, or type of treatment.

Patients with IIH whose symptoms and signs have resolved nevertheless have a risk for recurrence months to years later, particularly if they gain weight over a short period.10,37 Similarly, patients with IIH whose symptoms and signs have been stable for months to years may experience worsening, again often associated with rapid weight gain.37 Thus, all patients with IIH should be told of these risks and should be observed closely or at least be told to contact their physician should they experience a recurrence or worsening of their symptoms or signs.

Agarwal MR, Yoo JH. Optic nerve sheath fenestration for vision preservation in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E7.

Ball AK, Clarke CE. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:433-442.

Banik R, Lin D, Miller NR. Prevalence of Chiari I malformation and cerebellar ectopia in patients with pseudotumor cerebri. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:71-75.

Bruce BB, Preechawat P, Newman NJ, et al. Racial differences in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2008;70:861-867.

Çelebisoy N, Gökçay F, Sirin H, et al. Treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension: topiramate vs acetazolamide, an open-label study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:322-327.

Corbett JJ, Mehta MP. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in normal obese subjects and patients with pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1983;33:1386-1388.

Curry WTJr, Butler WE, Barker FGII. Rapidly rising incidence of cerebrospinal fluid shunting procedures for idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the United States, 1988-2002. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:97-108.

Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, et al. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:635-641.

Donnet A, Metellus P, Levrier O, et al. Endovascular treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Clinical and radiologic outcome of 10 consecutive patients. Neurology. 2008;70:641-647.

Feldon SE. Visual outcomes comparing surgical techniques for management of severe idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E6.

Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:138-145.

Frisén L. Swelling of the optic nerve head: a staging scheme. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982;45:13-18.

Garton JHL. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion procedures. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:146-155.

Higgins JNP, Tipper G, Varley M, et al. Transverse sinus stenoses in benign intracranial hypertension demonstrated on CT venography. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:137-140.

Johnson LN, Krohel GB, Madsen RW, et al. The role of weight loss and acetazolamide in the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Ophthalmology. 1998;105:2313-2317.

Kupersmith MJ, Gamell L, Turbin R, et al. Effects of weight loss on the course of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in women. Neurology. 1998;50:1094-1098.

Lee AG, Golnik K, Kardon R, et al. Sleep apnea and intracranial hypertension in men. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:482-485.

Lin A, Foroozan R, Danesh-Meyer HV, et al. Occurrence of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in patients with presumed idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2281-2284.

McGirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri–associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:627-632.

Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:597-617.

Rohr A, Dörner L, Stingele R, et al. Reversibility of venous sinus obstruction in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;29:656-659.

Schirmer CM, Hedges TR3rd. Mechanisms of visual loss in papilledema. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E5.

Shah VA, Kardon RH, Lee AG, et al. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The Iowa experience. Neurology. 2008;70:634-640.

Sugarman HJ, Felton WLIII, Sismanis A, et al. Gastric surgery for pseudotumor cerebri associated with severe obesity. Ann Surg. 1999;229:634-642.

Thambisetty M, Lavin PJ, Newman NJ, et al. Fulminant idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2007;68:229-232.

Vaphiades M, Vaphiades MS, Eggenberger ER, et al. Resolution of papilledema after neurosurgical decompression for primary Chiari I malformation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:673-678.

Wall M, Hart WMJr, Burde RM. Visual field defects in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:654-669.

1 Quincke H. Uber meningitis serosa and verewandte zustande. Dtsch Z Nervenheilk. 1897;9:149-168.

2 Warrington WB. Intracranial serous effusions of inflammatory origin: meningitis ependymitis serosa—meningism—with note on “pseudo-tumors” of the brain. Q J Med. 1914;7:93-118.

3 Foley J. Benign forms of intracranial hypertension: “toxic” and “otitic hydrocephalus.”. Brain. 1955;78:1-41.

4 Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:138-145.

5 Ball AK, Clarke CE. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:433-442.

6 Rangwala LM, Liu GT. Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:597-617.

7 Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri. Population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:875-877.

8 Radhakrishanan K, Ahlskog JE, Cross SA, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): descriptive epidemiology in Rochester, Minn, 1976-1990. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:78-80.

9 Brazis PW. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:683-684.

10 Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, et al. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:635-641.

11 Bruce BB, Preechawat P, Newman NJ, et al. Racial differences in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2008;70:861-867.

12 Winner P, Bello L. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in a young child without visual symptoms or signs. Headache. 1996;36:574-576.

13 Wall M, George D. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a prospective study of 50 patients. Brain. 1991;114:155-180.

14 Friedman DI. Pseudotumor cerebri presenting as headache. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:397-407.

15 Digre K. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:217-225.

16 Thambisetty M, Lavin PJ, Newman NJ, et al. Fulminant idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2007;68:229-232.

17 Schirmer CM, Hedges TR3rd. Mechanisms of visual loss in papilledema. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E5.

18 Hoye VJ3rd, Berrocal AM, Hedges TR3rd, et al. Optical coherence tomography demonstrates subretinal macular edema from papilledema. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1287-1290.

19 Rowe FJ. Ocular motility disturbances in benign intracranial hypertension. Br Orthop J. 1996;53:22-24.

20 Felton WL, Sismanis A. Otologic aspects of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in patients with and without papilledema. Neuroophthalmology. 1996;16(suppl):279. 1996

21 Corbett JJ. Problems in the diagnosis and treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. Can J Neurol Sci. 1983;10:221-229.

22 Kleinschmidt JJ, Digre KB, Hanover R. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: relationship to depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Neurology. 2000;54:319-324.

23 Huna-Baron R, Landau K, Rosenberg M, et al. Unilateral swollen disc due to increased intracranial pressure. Neurology. 2001;56:1588-1590.

24 Frisén L. Swelling of the optic nerve head: a staging scheme. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982;45:13-18.

25 Spence JD, Amacher AL, Willis NR. Benign intracranial hypertension without papilledema: role of 24-hour cerebrospinal fluid pressure monitoring in diagnosis and management. Neurosurgery. 1980;34:1509-1511.

26 Torun N, Sharpe JA. Pseudotumor cerebri mimicking Foster Kennedy syndrome. Neuroophthalmology. 1996;16:55-57.

27 Said RR, Rosman P. A negative cranial computed tomographic scan is not adequate to support a diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:609.

28 Lin A, Foroozan R, Danesh-Meyer HV, et al. Occurrence of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in patients with presumed idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2281-2284.

29 Pendse S, Bilyk JR, Olivia C, et al. Now you see it. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:177-182.

30 Banik R, Lin D, Miller NR. Prevalence of Chiari I malformation and cerebellar ectopia in patients with pseudotumor cerebri. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247:71-75.

31 Corbett JJ, Mehta MP. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in normal obese subjects and patients with pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1983;33:1386-1388.

32 Bono L, Lupo MR, Serra P, et al. Obesity does not induce abnormal CSF pressure in subjects with normal cerebral MR venography. Neurology. 2002;59:1641-1643.

33 Czosnyka M, Pickard JD. Monitoring and interpretation of intracranial pressure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:813-821.

34 Khandhar S, Friedman DI. Cerebrospinal fluid measurements in patients experiencing severe, benign headaches. Headache. 2003;43:553-554.

35 Digre KB, Corbett JJ. Pseudotumor cerebri in men. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:866-872.

36 Digre KB, Corbett JJ. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): a reappraisal. Neurologist. 2001;7:62-67.

37 Shah VA, Kardon RH, Lee AG, et al. Long-term follow-up of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The Iowa experience. Neurology. 2008;70:634-640.

38 Corbett JJ, Savino PJ, Thompson HS, et al. Visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Follow-up of 57 patients from 5 to 41 years and a profile of 14 patients with permanent severe visual loss. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:461-474.

39 Bastin ME, Sinha S, Farrall AJ, et al. Diffuse brain oedema in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1693-1696.

40 Owler BK, Higgins JNP, Péna A, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of benign intracranial hypertension: absence of cerebral oedema. Br J Neurosurg. 2006;20:79-81.

41 Subramanian PS, Goldenberg-Cohen N, Shukla S, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels are normal in obese patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:109-113.

42 Fishman RA. The pathophysiology of pseudotumor cerebri: an unsolved puzzle. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:257-258.

43 Wall M, Hart WMJr, Burde RM. Visual field defects in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:654-669.

44 Orcutt JC, Page NGR, Sanders MD. Factors affecting visual loss in benign intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1303-1312.

45 El-Dairi MA, Holgado S, O’Donnell F, et al. Optical coherence tomography as a tool for monitoring pediatric pseudotumor cerebri. J AAPOS. 2007;11:564-570.

46 Stiebel-Kalish H, Kalish Y, Lusky M, et al. Puberty as a risk factor for less favorable visual outcome in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:279-283.

47 Bruce BB, Kedar S, Van Stavern GP, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in men. Neurology. 2009;72:304-309.

48 Lee AG, Golnik K, Kardon R, et al. Sleep apnea and intracranial hypertension in men. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:482-485.

49 Vaphiades M, Vaphiades MS, Eggenberger ER, et al. Resolution of papilledema after neurosurgical decompression for primary Chiari I malformation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:673-678.

50 Kupersmith MJ, Gamell L, Turbin R, et al. Effects of weight loss on the course of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in women. Neurology. 1998;50:1094-1098.

51 Johnson LN, Krohel GB, Madsen RW, et al. The role of weight loss and acetazolamide in the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Ophthalmology. 1998;105:2313-2317.

52 Friedman DI, Streeten DHP. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and orthostatic edema may share a common pathogenesis. Neurology. 1998;50:1099-1104.

53 Sugarman HJ, Felton WLIII, Sismanis A, et al. Gastric surgery for pseudotumor cerebri associated with severe obesity. Ann Surg. 1999;229:634-642.

54 Nadkarni T, Rekate HL, Wallace D. Resolution of pseudotumor cerebri after bariatric surgery for related obesity. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:878-880.

55 Singh S, Kumar A. Wernicke encephalopathy after obesity surgery: a systematic review. Neurology. 2007;68:807-811.

56 Friedman DI, Eller PE. Topiramate for treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Headache. 2003;43:592.

57 Alore PL, Jay WM, Macken MP. Topiramate, pseudotumor cerebri, weight-loss and glaucoma: an ophthalmologic perspective. Semin Ophthalmol. 2006;21:15-17.

58 Çelebisoy N, Gökçay F, Sirin H, et al. Treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension: topiramate vs acetazolamide, an open-label study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:322-327.

59 Shah VA, Fung S, Shahbaz R, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:617-618.

60 Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT. Adverse ocular drug reactions recently identified by the National Registry of Drug-Induced Ocular Side Effects. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1275-1279.

61 Friedman DI, Rausch EA. Headache diagnoses in patients with treated idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;58:1551-1553.

62 Fishman RA. Anatomical aspects of the cerebrospinal fluid. In: Fishman R, editor. Cerebrospinal Fluid in Diseases of the Nervous System. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1992:20-21.

63 Guçer G, Viernstein L. Long-term intracranial pressure recording in the management of pseudotumor cerebri. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:256-263.

64 Jefferson A, Clark J. Treatment of benign intracranial hypertension by dehydrating agents with particular reference to the measurement of the blindspot area as a means of recording improvement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:627-639.

65 Liu GT, Glaser JS, Schatz N. High-dose methylprednisolone and acetazolamide for visual loss in pseudotumor cerebri. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:88-96.

66 Friedman DI. Papilledema and pseudotumor cerebri. Neurol Clin. 2001;14:129-147.

67 Garton JHL. Cerebrospinal fluid diversion procedures. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24:146-155.

68 Feldon SE. Visual outcomes comparing surgical techniques for management of severe idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E6.

69 McGirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri–associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:627-632.

70 Eggenberger ER, Miller NR, Vitale S. Lumboperitoneal shunt for the treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1996;46:1524-1530.

71 Burgett RA, Purvin VA, Kawasaki A. Lumboperitoneal shunting for pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1997;49:734-739.

72 Chumas PD, Armstrong DC, Drake JM, et al. Tonsillar herniation: the rule rather than the exception after lumboperitoneal shunting in the pediatric population. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:568-573.

73 Sullivan HC. Fatal tonsillar herniation in pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology. 1991;41:1142-1144.

74 Bynke G, Zemack G, Bynke G, et al. Ventriculoperitoneal shunting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2004;63:1314-1316.

75 Curry WTJr, Butler WE, Barker FGII. Rapidly rising incidence of cerebrospinal fluid shunting procedures for idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the United States, 1988-2002. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:97-108.

76 Lee MC, Yamini B, Frim DM. Pseudotumor cerebri patients with shunts from the cisterna magna: clinical course and telemetric intracranial pressure data. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1094-1099.

77 Thuente DD, Buckley EG. Pediatric optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:724-727.

78 Chandrasekaran S, McCluskey P, Minassian D, et al. Visual outcomes for optic nerve sheath fenestration in pseudotumour cerebri and related conditions. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:661-665.

79 Abbasian J, Lee AG, Longmuir R, et al. Rapid regression of retinochoroidal venous collaterals following optic nerve sheath fenestration in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Semin Ophthalmol. 2007;22:35-37.

80 Agarwal MR, Yoo JH. Optic nerve sheath fenestration for vision preservation in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):E7.

81 Yazici Z, Yazici B, Tuncel E. Findings of magnetic resonance imaging after optic nerve sheath decompression in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:429-435.

82 Kaye AH, Galbraith JEK, King J. Intracranial pressure following optic nerve decompression for benign intracranial hypertension. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:453-456.

83 Jacobson EE, Johnston IH, McCluskey P. The effects of optic nerve sheath decompression on cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Neuroophthalmology. 1996;16(suppl):290.

84 Nguyen R, Carta A, Geleris A, et al. Long-term effect of optic sheath decompression on intracranial pressure in pseudotumor cerebri. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:S388.

85 King JO, Mitchell PJ, Thomson KR, et al. Cerebral venography and manometry in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 1995;45:2224-2228.

86 Karahalios DG, Rekate HL, Khayata MH, et al. Elevated intracranial venous pressure as a universal mechanism in pseudotumor cerebri of varying etiologies. Neurology. 1996;46:198-202.

87 Farb RI, Vanek I, Scott JN, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The prevalence and morphology of sinovenous stenosis. Neurology. 2003;60:1418-1424.

88 Higgins JNP, Tipper G, Varley M, et al. Transverse sinus stenoses in benign intracranial hypertension demonstrated on CT venography. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19:137-140.

89 King JO, Mitchell PJ, Thomason KR, et al. Manometry combined with cervical puncture in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;58:26-30.

90 Scoffings DJ, Pickard JD, Higgins JNP. Resolution of transverse sinus stenoses immediately after CSF withdrawal in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:911-912.

91 Corbett JJ, Digre K. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. An answer to, “the chicken or the egg?”. Neurology. 2002;58:5-6.

92 Bono F, Giliberto C, Mastrandrea C, et al. Transverse sinus stenoses persist after normalization of the CSF pressure in IIH. Neurology. 2005;65:1090-1093.

93 Higgins JNP, Cousins C, Owler BK, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: 12 cases treated by venous sinus stenting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1662-1666.

94 Owler BK, Parker G, Halmagyi GM, et al. Pseudotumor cerebri syndrome: venous sinus obstruction and its treatment with stent placement. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:1045-1055.

95 Rohr A, Dörner L, Stingele R, et al. Reversibility of venous sinus obstruction in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;29:656-659.

96 Donnet A, Metellus P, Levrier O, et al. Endovascular treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Clinical and radiologic outcome of 10 consecutive patients. Neurology. 2008;70:641-647.

97 Shapiro S, Yee R, Brown H. Surgical management of pseudotumor cerebri in pregnancy: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:829-831.

98 Huna-Baron R, Kupersmith MJ. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in pregnancy. J Neurol. 2002;249:1078-1081.

99 Lee AG, Pless M, Falardeau J, et al. The use of acetazolamide in idiopathic intracranial hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:855-859.

100 McDonnell GV, Patterson VH, McKinstry S. Cerebral venous thrombosis occurring during an ectopic pregnancy and complicated by intracranial hypertension. Br J Clin Pract. 1997;51:194-197.