18 Pseudoneoplastic Lesions of the Lungs and Pleural Surfaces

There is a limited group of pulmonary lesions that one can classify as pseudoneoplastic, but their conditions comprise a significant aggregation in absolute numbers. Some are categorized as malformative or reactive, including pulmonary hamartomas; selected inflammatory pseudotumors (“plasma cell granulomas”); tumefactive lymphoid hyperplasias; inflammatory or reparative conditions simulating carcinomas; unusual granulomatous reactions; tumefactive pleural plaques; and florid examples of mesothelial hyperplasia. Other clinical “pseudotumors” such as amyloidoma and rounded atelectasis1 are confused with neoplasms only by nonpathologists and are not included for discussion here. On the other hand, the variant of inflammatory pseudotumor now known as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor demonstrates clonal characteristics and can rightly be regarded as a true neoplasm.2,3 Accordingly, it likewise has been omitted from this chapter.

Pulmonary Hamartoma

The term hamartoma is intended to denote tumefactive malformations that exhibit an architecturally abnormal relationship between tissue components that are appropriate to the organ site in which they arise.4 Other terms for these lesions in the lung include benign mesenchymoma, fibroma, chondroma, fibrochondrolipoma, fibrolipomyochondroma, hamartoma-chondroma, cartilage-containing tumor of the lung, adenochondroma, lipochondroadenoma, adenofibrolipochondromyxoma, and mixed tumor.5 Although in the past, chondroma has been used interchangeably with the lesion referred to here as hamartoma, they constitute distinct lesions and are discussed in Chapter 19.

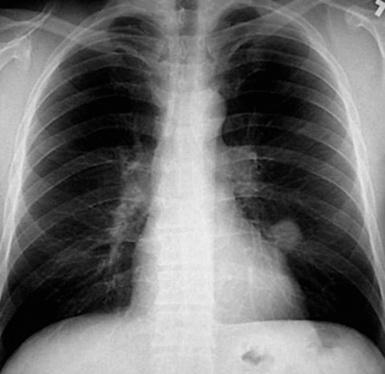

Pulmonary hamartomas (PHs) have been encountered in approximately 0.25% of autopsies.6 They can arise both centrally and peripherally, and the latter are more common in men than women.7–10 Radiographically, hamartomas are typically found incidentally, usually in patients between 40 and 60 years of age; nevertheless, pediatric cases have also been reported.10 They are only rarely multiple. Hamartomas may coexist with primary or secondary malignancies of the lung.11,12 Under these circumstances, the hamartomatous lesions may be mistaken for intrapulmonary metastases or synchronous primary carcinomas, particularly if they lack internal calcification.

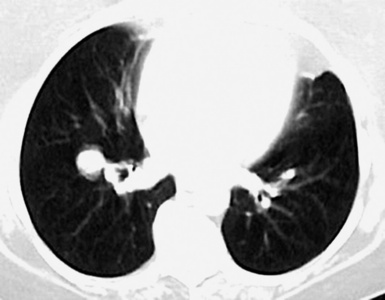

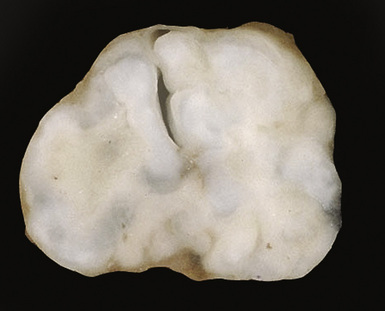

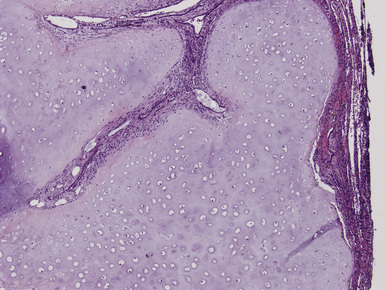

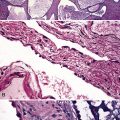

Macroscopically, most PHs are peripherally located, and they sometimes show a topographical relationship to small bronchi or bronchioles.13–16 They rarely penetrate the visceral pleura.17 They are usually well-demarcated (Figs. 18-1 and 18-2) and range from several millimeters to 20 cm in diameter. The central form of hamartoma is encountered in association with large bronchi, as an endoluminal polypoid protuberance covered by intact mucosa.10 All hamartomas of the lung are lobulated, and their cut surfaces reflect their constituent cells (Figs. 18-3 and 18-4). Most of these lesions contain predominantly cartilaginous tissue and are therefore firm to hard, relatively homogeneous, and translucent when transected.

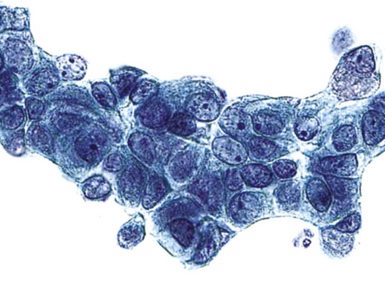

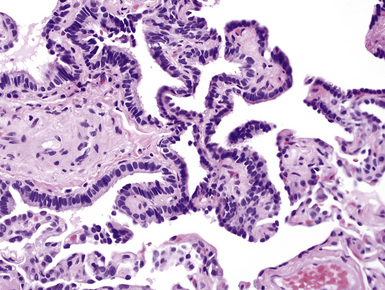

On histologic examination, PHs are manifested by mature mesenchymal tissues but with abnormal configurations. These elements are usually represented by hyaline cartilage, but fibrous tissue, smooth muscle, adipocytic components, and bone18 may be seen. Those masses lacking chondroid elements have sometimes been diagnosed as “intrabronchial lipoma,” “myxoma,” “leiomyoma,” or “fibroadenoma.”13–16 During the growth of PHs, the mesenchymal portions of the lesion engulf and trap small tubular airways, and the latter structures thus spuriously appear to represent an integral part of the lesion (Figs. 18-5 and 18-6). Entrapped alveolar epithelium may also undergo cuboidal or low-columnar metaplasia. Epithelial hyperplasia and papillae may be present in the entrapped epithelium (Fig. 18-7). Indeed, the last of these changes can be prominent and bear a resemblance to placental tissue,19 a feature referred to as “placental transmogrification.” The presence of entrapped epithelium is one of the key distinguishing features of PH from “true” pulmonary chondroma. Transthoracic fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is a common method for the initial pathologic sampling of mass lesions in the lung. In fact, if PH is the favored diagnosis of the radiologist, FNAB is usually done with the anticipation that a thoracotomy can be avoided if that interpretation is correct. The cytologic features of PH include the presence of dispersed fusiform and stellate cells in a myxoid background, as seen histologically (see Fig. 18-7B). Chondroid material is also present in a majority of cases.20–22

Nevertheless, FNAB of PH may, in fact, result in the very outcome it intends to avoid: namely, formal surgical resection because of a suspicion of malignancy. Some cytologic specimens of PH show atypical epithelial cells with enlarged nuclei, mimicking low-grade adenocarcinoma (see Fig. 18-7C), sometimes adjacent to stromal tissues resembling the pattern seen in some fibroadenomas of the breast in FNAB samples. This can easily lead to a false-positive interpretation of carcinoma.23 Surfactant-containing intranuclear inclusions can be seen in the trapped epithelium of PH,24 like those observed in bronchioloalveolar carcinomas, further suggesting the diagnosis of carcinoma.

Electron microscopic studies of PH show primitive stellate fibroblastic cells with transitional forms to cartilaginous foci.25,26

Cytogenetic evaluations have demonstrated an abnormal karyotype in several instances, principally represented by an exchange of material among various chromosomes.27–30 These data beg the question of whether PH might actually be neoplastic after all, but the clinical evolution of this lesion (see subsequent discussion) generally speaks against such a possibility.

PH must be distinguished from primary or metastatic mesenchymal malignancies in the lungs, as well as primary or secondary biphasic sarcomatoid carcinomas.31–34 The presence of multinucleated cells, nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis, and mitotic activity is rare in PH, in contrast to these diagnostic alternatives. In histologically similar biphasic carcinomas (Fig. 18-8), keratin immunoreactivity is present both in the mesenchymal-like and the overtly epithelial components, whereas PH shows reactivity for epithelial markers only in trapped epithelial elements. True chondromas of the lung tend to be multiple and comprised of only cartilage, which is smoothly circumscribed. In contrast, PHs occur singly, and contain multiple tissue types and entrapped, invaginated epithelium.

PHs continue to enlarge slowly if left in place after diagnosis, but they rarely cause significant clinical difficulty. Simple excision of the lesions is typically performed today, especially with the availability of thoracoscopic video-assisted surgical techniques.35 Laser treatment has also been offered for patients with central PHs.36 The clinical result of these treatments is excellent in virtually all cases.

Returning to the question of whether PH might be neoplastic, Pelosi and colleagues have reported exceptional cases in which a malignancy appears to evolve from this lesion.37 In particular, these authors observed the patterns of malignant mixed tumor and malignant myoepithelioma in association with PH.

Inflammatory Pseudotumor—Plasma Cell Granuloma of the Lung

The most common form of the proliferative spindle cell lesion known as inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) of the lung has undergone scrutiny in the recent past and is generally regarded currently as a true neoplasm composed of myofibroblasts.2,3 That particular entity had been called the fibrohistiocytic subtype of pulmonary pseudotumor38–40 but has now been renamed inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT).3 The lesion known as calcifying fibrous pseudotumor41–44 may represent a closely related entity, at least in some cases, and is bound to IMT by its common manifestation of a t(2;17) chromosomal translocation and a potential expression of the ALK-1 protein.45–47 Other lesions of the lung that have been included in the category of IPT—namely, plasma cell granuloma and hyalinizing granuloma46–54—probably do represent non-neoplastic masses with variable etiologies. Both of them are composed of inflammatory and mesenchymal cells, potentially including mature lymphocytes, plasma cells, mast cells, macrophages, eosinophils, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts. There is also likely overlap between some of these lesions and those described in association with IgG4 sclerosing disease (see later discussion).

As just defined, the true incidence of pulmonary IPTs that are not IMTs is uncertain. IPTs are not commonly encountered in general surgical pathology practice, but their frequency is somewhat dependent on definitions. Some observers have used IPT broadly, to describe both circumscribed nodules and large irregular inflammatory masses, or segmental and lobar consolidations,55 whereas others have almost abandoned the term altogether, preferring a more descriptive diagnosis for most cases, such as organizing pneumonia.

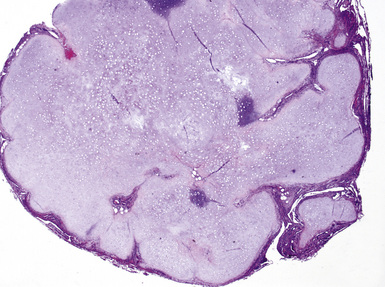

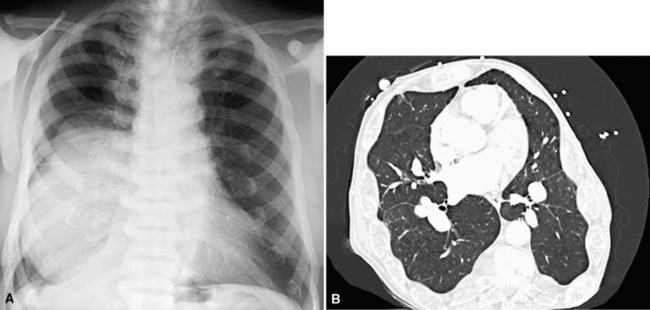

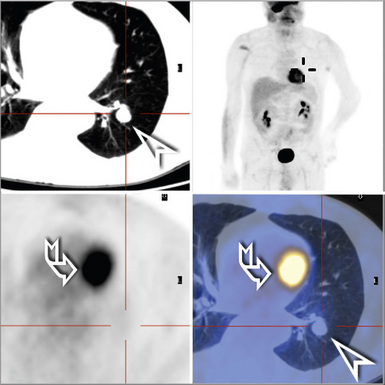

This lesion shows no sex predilection and occurs over a broad age range, from 1 to 77 years, with a mean of 27 to 50 years.40 Approximately 50% of patients complain of cough, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, chest pain, or combinations thereof. Chest radiographs usually show a single, sharply marginated, round or oval mass (Fig. 18-9), but the edges of large lesions may be more ill-defined.56,57 Some IPTs involve the pleural surface and retract it as seen on computed tomography (CT) of the thorax57; as expected, these findings may falsely suggest the possibility of malignancy. Calcification and cavitation also are potentially present in IPTs, and these features may also be present in imaging.

Pulmonary IPTs range in size from 0.5 to larger than 30 cm.39,40 Most have well-defined margins macroscopically but do not have a true fibrous capsule, and the color and texture is variable. Those that contain numerous inflammatory cells are tan-white and fleshy, and those with a predominance of mesenchymal tissue are gray and firm. IPTs with secondary xanthomatization may be bright yellow and friable. Some IPT also exhibit areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, and/or calcification. Rarely IPTs are comprised of sessile intrabronchial masses, whereas others are attached to the pleura. In typical pulmonary IPT, the microscopic architecture of the lung is replaced by a fibroinflammatory proliferation. Depending on their dominant cellular elements and major growth patterns, IPTs may be subclassified into two types: namely, tumefactive organizing pneumonia-like and lymphoplasmacytic variants.39 These may simply represent different stages in the evolution of IPT, but recent publications suggest that lymphoplasmacytic IPT (LPIPT) is distinctive as part of systemic fibrosing autoimmune disorders that feature the presence of numerous IgG4-producing plasma cells.58–61

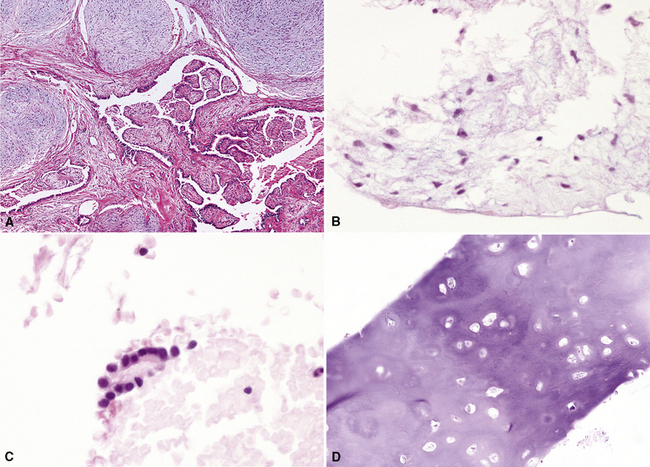

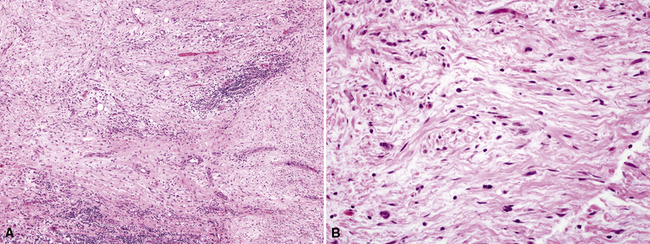

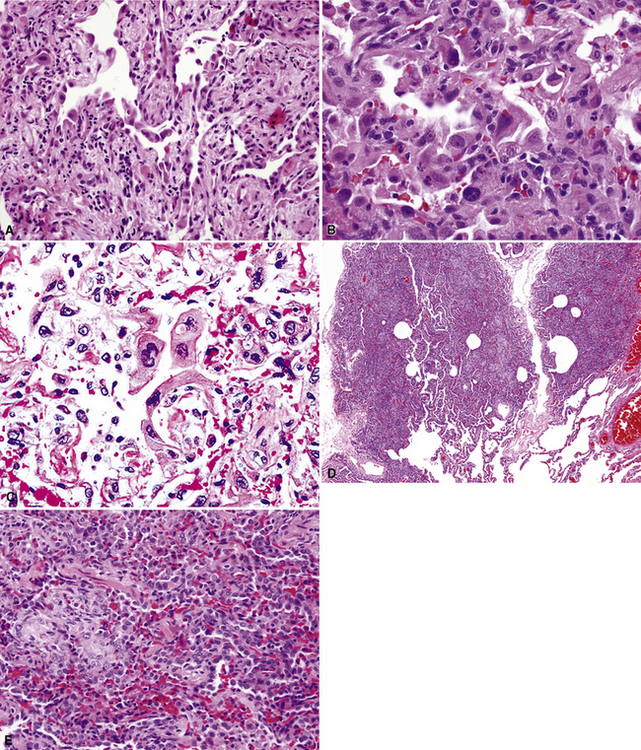

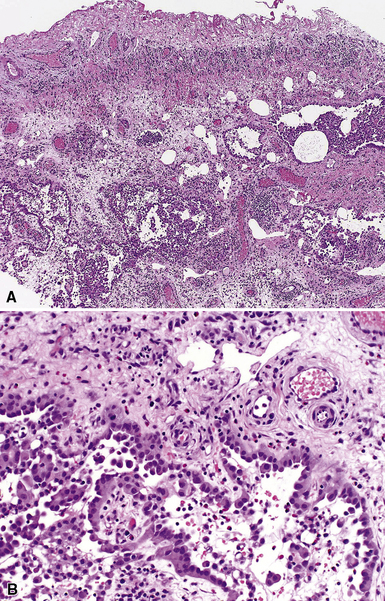

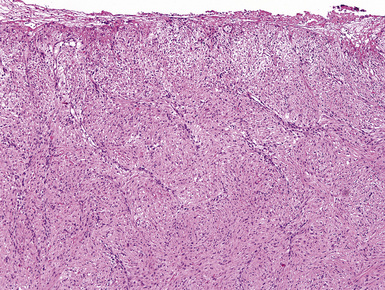

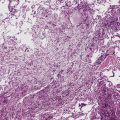

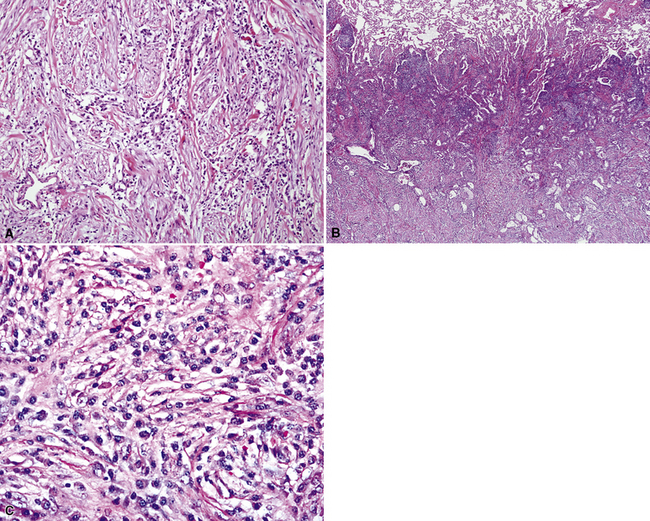

The organizing pneumonia-like variant shows intra-alveolar lymphohistiocytic inflammation and peripheral as well as central fibrosis (Figs. 18-10 and 18-11). Fibroblastic proliferation is admixed with fibrinoinflammatory exudate in alveoli, alveolar ducts, and bronchioles. The alveolar architecture is preserved in early lesions and the peripheral portions of “mature” IPT but is generally obscured by superimposed fibrous tissue, which tends to assume a whorled configuration (Figs. 18-12 and 18-13). Neutrophils are sometimes interspersed with the lymphocytes and plasma cells, and they may form intralesional microabscesses that result in small areas of cavitation. Alveoli bordering IPTs are often filled with foamy macrophages and mantled by hyperplastic pneumocytes. Multinucleated cells of the Touton type are sometimes present, as are foci of dystrophic calcification, osseous metaplasia, or myxomatous change. Lipoid pneumonia may develop adjacent to areas where IPTs have caused bronchial obstruction by intraluminal proliferation or impingement on an airway. Late in the evolution of IPTs and in their central aspects, the lung parenchyma is replaced by deposition of mature collagen in broad bundles that transect the lesion; it may sometimes assume a keloidal appearance.

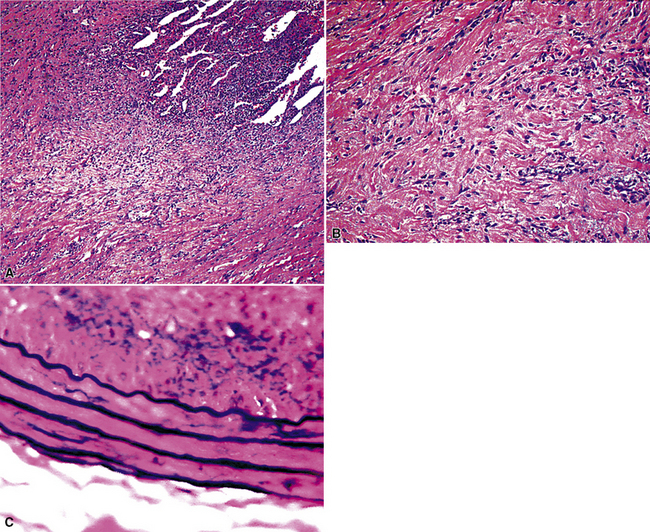

Figure 18-11 A to C, Marked chronic inflammation—with numerous plasma cells—and sclerosis in pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor.

In the LPIPT variant, plasma cells and lymphocytes comprise the bulk of the lesion; germinal centers and a paucicellular collagenous matrix may also be prominent.58–61 Fibroblasts and xanthoma cells are usually relatively scant. To some degree, the two histologic subtypes of IPT do overlap one another morphologically. As mentioned earlier, the immunohistologic presence of numerous IgG4-positive plasmacytes tends to strongly favor a diagnosis of LPIPT. Other findings that may suggest LPIPT are the presence of endothelialitis, prominent organization, lymphangitic inflammatory infiltrates that are rich in plasma cells and histiocytes (with or without the presence of a mass), and fibrinous pleuritis. Prominently dilated lymphatic spaces, containing histiocytes that show emperipolesis of lymphocytes, may also be observed.

Neither form of IPT is composed of solid sheets of lymphocytes or plasma cells, tending to prevent diagnostic confusion with lymphoma or plasmacytoma. Nevertheless, rearrangement of the immunoglobulin heavy chain genes in a subset of LPIPT cases has been reported, raising the possibility that these particular lesions might be neoplastic or preneoplastic.62

Lymphocytic infiltration and scarring of vascular walls in some examples of IPT, often in association with organizing thrombi, have also been described.39 These changes may be secondary rather than a reflection of a primary vasculitic process. Usually, both kappa and lambda light chain immunoglobulins are detectable immunohistologically in the plasma cells, indicating a polytypic population51; lymphocyte subset markers similarly show an admixture of B cells and T cells.3

The specific etiologic factors underlying the development of pulmonary IPT are largely unknown. The premise that some cases represent a peculiar form of localized pneumonia has support from a history of a previous febrile illness with respiratory complaints in up to 40% of cases. Some case reports have suggested that there is an overlap in appearance between IPT and tumefactive pulmonary infections with aspergillus, rickettsiae, mycoplasma, various viruses, mycobacteria, Cryptococcus, corynebacteria, and other microorganisms.55–57,63–69 Rare examples have also been documented after trauma to the lung,70 and some cases arise from prior aspiration. As stated earlier, current hypotheses hold that some LPIPT are probably part of a systemic autoimmune process.58–61

The differential diagnosis of pulmonary IPT has been partially cited previously. It includes plasmacytoma,71 malignant lymphoma,72,73 and lymphoid hyperplasia,74 selected examples of sclerosing hemangioma of the lung (called epithelial plasma cell granuloma-like tumors by Michal and Mukensnabl75), the peculiar variant of lung cancer known as inflammatory sarcomatoid carcinoma76 (see Chapter 14), and IMT.2,3 Among those conditions, plasmacytomas are recognized by their monotypism for cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, and selected lymphomas may also demonstrate this characteristic. Furthermore, malignant lymphomas are generally less well-circumscribed than IPTs and exhibit more cytologically monotonous infiltrates of atypical lymphoid cells. Localized and diffuse forms of pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia are composed predominantly of mature lymphocytes, in contrast to the heterogeneous cellular composition of IPTs. Inflammatory sarcomatoid carcinoma can be separated from inflammatory simulators by its diffuse immunoreactivity for keratin, and IMTs contain significantly fewer IgG4-positive cells than those seen in IPTs.60 There is some minor difference of opinion as to whether pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma77 is a part of the spectrum of IPT in the lung. Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma shows more lamellar hyalinized collagen than is seen in classical IPT. Hyalinizing granulomas of the lung are commonly multiple, whereas “usual” IPT is not.77 Sclerosing hemangiomas78 were once considered to be related to IPTs, but they are now appreciated as epithelial neoplasms with pneumocytic differentiation.79 The latter lesions may exhibit sclerosis, but they also contain aggregates of bland cuboidal cells together with micropapillary and angiomatoid areas. Inflammation is absent or scanty in sclerosing hemangiomas, and their constituent cells express thyroid transcription factor-179; those of IPT do not. Ledet and associates80 have examined the utility of immunostains for mutant p53 protein in the diagnostic separation of IPTs from low-grade intrapulmonary sarcomas. In their hands, p53 was restricted to malignant lesions, albeit with less than absolute sensitivity for such tumors.

Some examples of pulmonary IPT have been monitored for extended periods of time before excision or autopsy examination.81–83 Information from these cases indicates that the lesions tend to remain stable or grow very slowly. Spontaneous resolution has also been documented, and a few lesions have shrunk after small incisional biopsy or administration of systemic corticosteroids or irradiation.81,83 Surgical removal is usually necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis of IPT, and, if the lesion has been completely excised, no further therapy is needed.56 Long-term follow-up of patients with pulmonary IPTs has revealed no untoward clinical events in such cases.

Mycobacterial Spindle Cell Pseudotumor

Spindle cell pseudotumors that are reactions to mycobacterial infection have been documented in several organ sites in immunosuppressed patients.84–86 These proliferations show a close histologic resemblance to histoid leprosy,87,88 and most reports have documented numerous intralesional mycobacteria (see Chapter 6). Only one case of mycobacterial pseudotumor (MP) has been reported in the lung,89 although we have anecdotally encountered another example in a 41-year-old male patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

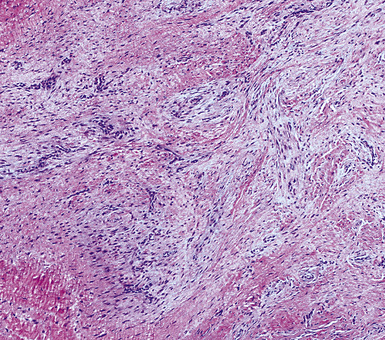

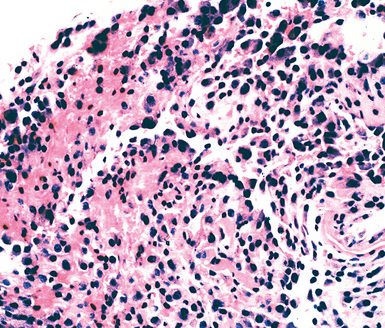

Grossly, the lesions appear as yellow-gray nodules. They may show a predilection for small airways. Microscopically, the lesions are comprised of aggregates of spindle cells with a fascicular growth pattern and without significant atypia or mitoses. Scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells may be present, but overt granulomas are lacking. The cytoplasm of the spindle cells is “foamy” but may contain hemosiderin focally. The lesional cells are immunoreactive for lysozyme, with no labeling for S100 protein, keratin, actin, desmin, or von Willebrand factor. Ziehl-Neelsen staining shows innumerable acid-fast bacilli in the fusiform cells (Figs. 18-14 to 18-16). Most examples of MP in other anatomic locations have been related to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare or Mycobacterium kansasii.

Another reported feature of MPs in other sites is a possible source of diagnostic error. That is, a reproducible cross-reaction has been seen with mycobacterial antigens using certain desmin antibodies,90 spuriously suggesting the presence of a myogenous proliferation. This observation is especially troublesome in the setting being discussed here, because smooth muscle or myofibroblastic tumors enter prominently into the differential diagnosis of MPs. However, a documented lack of immunoreactivity for actin and electron microscopic attributes that support histiocytic differentiation in MP argue against those alternative interpretations.

Other lesions that must be separated from pulmonary MP include Kaposi sarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, spindle cell melanoma, and neural proliferations.89 Obviously, acid-fast stains should be done in all spindle cell lesions from immunocompromised individuals, and these consistently confirm mycobacterial causation. In some instances, the nature of MP is more obvious because of overtly granulomatous foci in the lung tissue around the spindle cell lesion. Characteristics of malignancy such as necrosis, nuclear atypia, and pathologic mitoses are absent in MP.84–86 Thus, diagnoses of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, or other sarcomas would be unlikely.

Pseudoneoplastic Hematolymphoid Processes

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia may both be regarded as pseudoneoplasms. They are discussed in Chapter 15.

Rosai-Dorfman Disease (Sinus Histiocytosis with Massive Lymphadenopathy)

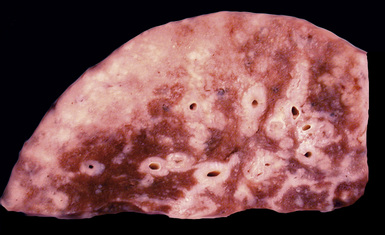

Most frequently, Rosai-Dorfman disease (sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy [SHML]) involves lymph nodes, but it may rarely involve the lung primarily.91,92 It can be seen in either sex and over a wide range of ages. Despite the name of this condition, lymphadenopathy does not always coexist with extranodal disease. When this condition affects the pulmonary parenchyma, it appears to have its epicenter in the hilar tissue and follows lymphatics peripherally into both lungs.91,93 Accordingly, chest radiographs show an accentuation of central bronchovascular markings and bilateral interstitial prominence. CT scans (Fig. 18-17) may show areas of pleural-based consolidation. Confluence of the infiltrates may yield masslike densities in the lung fields as well (Fig. 18-18). Interestingly, clinical evidence of associated immune dysfunction may be apparent, including autoantibody formation, polyarthritis, immune-complex glomerulonephritis, asthma, and juvenile diabetes mellitus. Fever, night sweats, and weight loss have also been reported.91 Justification for the classification of Rosai-Dorfman disease as non-neoplastic comes from molecular data indicating its polyclonal nature.91 Nevertheless, this condition may occasionally coexist with solid malignancies, including carcinomas of the lung.94,95 Such an association could arise, at least in part, from the aforementioned immunologic dysfunction in SHML.

Figure 18-18 Gross photograph of lung tissue in Rosai-Dorfman disease (from the same patient as Fig. 18-17). Note the lymphangitic pattern of involvement.

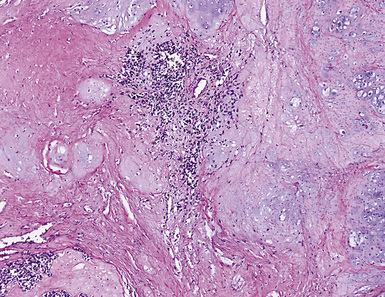

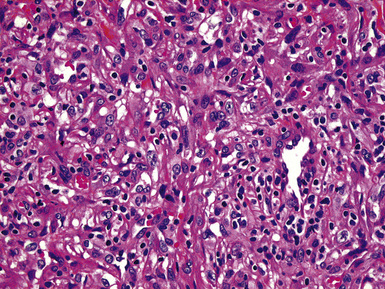

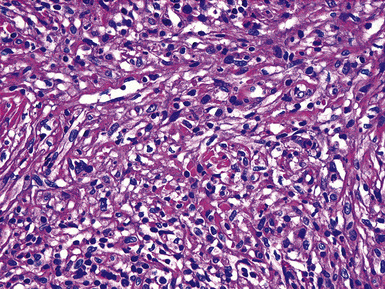

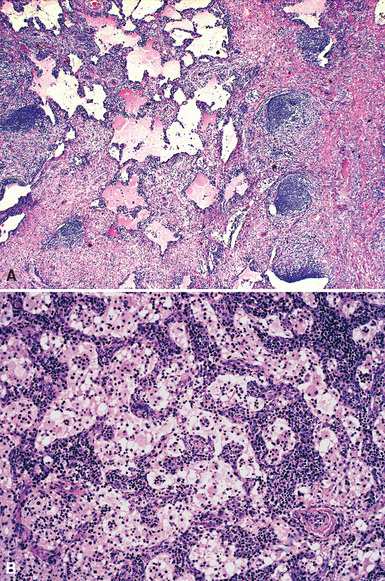

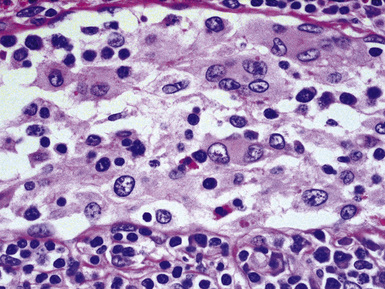

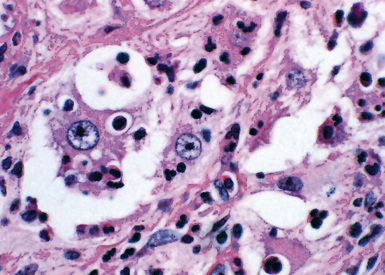

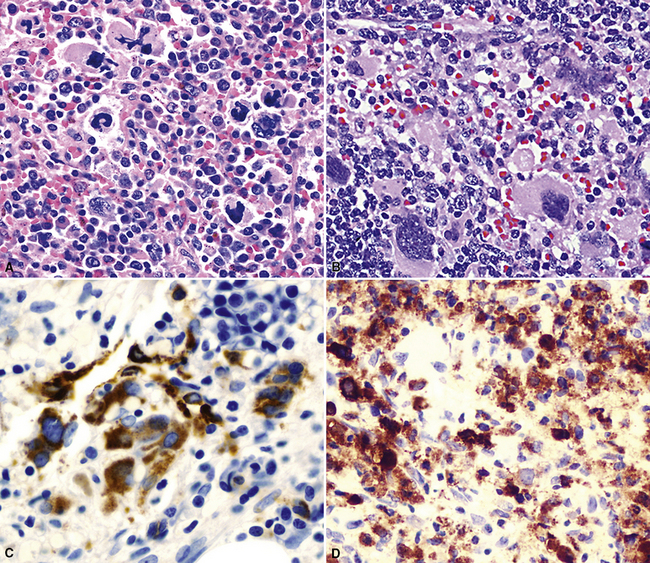

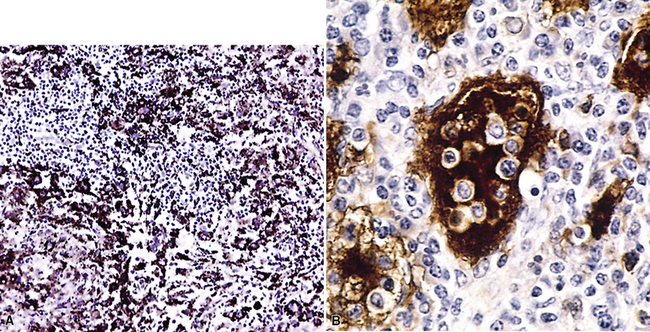

Pathologic specimens of the lung or lymph nodes in SHML demonstrate comparable morphologic findings. Dilated lymphatic spaces in the pulmonary parenchyma contain large pale histiocytes with abundant amphophilic cytoplasm, surrounded by lymphoid infiltrates that are punctuated by germinal centers and fibrous septa (Figs. 18-19 and 18-20). The large histiocytes demonstrate a peculiar tendency to engulf intact, mature lymphocytes, representing a phenomenon known as lymphemperipolesis (Fig. 18-21). The overall image of foci of SHML in extranodal sites is therefore reminiscent of abnormal lymph nodes.91 The immunophenotype of the lesional histiocytes is singular in that it features prominent reactivity for S100 protein (Fig. 18-22) and CD45 in the absence of CD1a. Labeling for CD68, lysozyme, MAC387, and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin may also be observed.

Figure 18-22 A and B, Intense immunoreactivity for S100 protein is seen in the lesional histiocytes of Rosai-Dorfman disease.

Differential diagnoses in cases of SHML potentially include metastatic carcinoma, metastatic melanoma, Erdheim-Chester disease, large cell lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma.91,92 The large tumor cells in the non-histiocytic conditions in this list differ from those in SHML immunohistologically, by their reactivity for keratin (in carcinoma), MART-1/melan-A (in melanoma), CD3 or CD20 (in non-Hodgkin lymphoma), and CD30 (in Hodgkin lymphoma). Practically speaking, with the exception of Erdheim-Chester disease—which is immunohistochemically indistinguishable from SHML and also characterized by bland histiocytes—all of the other conditions also show a much higher degree of cytologic atypia than that seen in SHML. Thus, special diagnostic studies are usually not required to make the cited distinctions.

The clinical course of Rosai-Dorfman disease is unpredictable. A comprehensive summary91 noted that patients with more than one site of extranodal disease and obvious immune dysfunction more often suffered significant morbidity and even mortality from this condition. Spontaneous remissions have been seen as well. Treatment is individualized, with antineoplastic therapy being reserved for those patients with serious organ dysfunction.

Extramedullary Hematopoiesis

In patients who have preexisting disorders of myelopoiesis, such as idiopathic myelofibrosis, hemoglobinopathies, severe hemolytic anemias, or Gaucher disease,96–101 myeloid tissue that has been nascent since infancy can potentially reappear in several extramedullary sites. The lung and pleura are included in that list. If the proliferation of such elements is sufficient, it may manifest itself as discrete masses within visceral structures or serosal surfaces, often imitating neoplasms radiographically.100

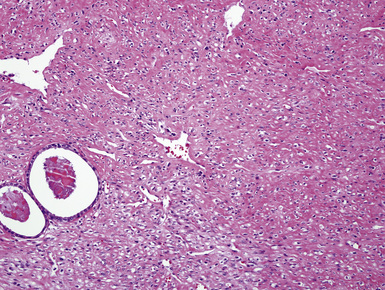

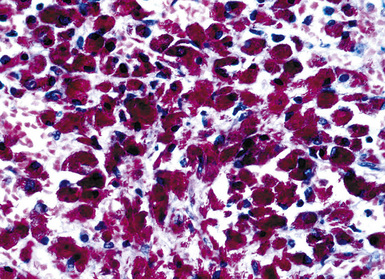

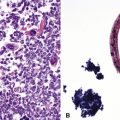

Fine needle aspiration or needle biopsy of extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH) demonstrates a variable mixture of erythroblasts, myeloid precursors, and megakaryocytes99 (Figs. 18-23 and 18-24). These cell lines are usually recognizable as such in routine sections; however, should confirmation of their identity be desired, Leder stain and immunostains for glycophorin-A, myeloperoxidase, and CD61 can be used (see Fig. 18-24).

Very uncommonly, EMH may serve as the seed bed for extramedullary leukemic transformation.102

Pseudoneoplastic Changes as a Consequence Of Lung Injury

Exfoliative cytology of the respiratory tract has been used effectively for several decades in the diagnosis of pulmonary disorders.103 Nonetheless, inherent shortcomings in this method have been well-documented, and some of them relate to the potential for the overdiagnosis of benign reparative or inflammatory conditions in the lungs as neoplastic. The incidence of this eventuality should be less than or equal to 0.25% of all cytologic specimens according to accepted standards.104 Generally speaking, similar pitfalls accompany the interpretation of small transbronchial biopsy specimens in surgical pathology.

There are several possible reasons for mistakes in the cytologic diagnosis of malignancy in the lung. One may simply misinterpret reparative conditions or inflammatory epithelial atypia as carcinoma, but this should be rare.105,106 Another potential source of confusion is the shedding or artifactual introduction of malignant cells from the mouth or upper airway into a sputum or bronchial washing specimen.107,108 Both of these scenarios are troublesome only if there are accompanying abnormalities on chest films that might cause clinicians to consider a neoplasm diagnostically. Thus, it is obvious that radiologic data are essential to optimal cytopathologic interpretation.

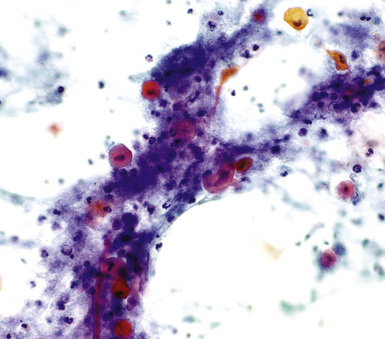

However, there are some mass lesions that may, under selected circumstances, incite benign but atypical epithelial proliferations in the surrounding lung. Exfoliated cells in these cases may thus be mistaken as carcinomatous. The underlying conditions associated with this trap include symptomatically “occult” pulmonary infarcts, granulomas, and bronchiectasis with surrounding pneumonia, typically associated with atypical squamous metaplasia in adjacent bronchi109–116 (Figs. 18-25 and 18-26). As expected, a misdiagnosis of squamous carcinoma is the usual error in such instances.

Another more heterogeneous collection of diseases that may imitate adenocarcinoma in cytologic samples or small biopsies includes radiation pneumonitis, postchemotherapy atypia in alveolar lining cells, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infarcts, viral pneumonias of various types, pulmonary vasculitides, lung injury caused by toxic chemicals, noninfectious interstitial pneumonitides, diffuse alveolar damage, and recurrent pneumothorax116–126 (see also Chapter 5) (Figs. 18-27 and 18-28). These conditions are again most misleading in the context of localized radiographic abnormalities in the lungs and when details of the clinical setting are not provided. Moreover, because of the broad roentgenographic spectrum of such tumors as bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma, including an imitation of uncomplicated pneumonia,127 the study of chest films is, unfortunately, an imperfect safeguard in this specific setting. In general, pseudomalignant glandular pulmonary metaplasias show greater cellular heterogeneity than that seen in true adenocarcinomas.128 Lower nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, “scalloping” of cell borders, and focal intercellular “windows” in pseudoneoplastic glandlike profiles also typify atypical metaplasias.

It is also important to realize that special techniques, such as immunostains for tumor-associated glycoprotein-72 (with the antibody B72.3), are not able to make the distinction in question and may even contribute further to misdiagnosis.129 Indeed, there are no universally effective methods to avoid mistakes in the cytologic or biopsy diagnosis of pulmonary malignancy. Patients and clinicians should probably be apprised of that reality.

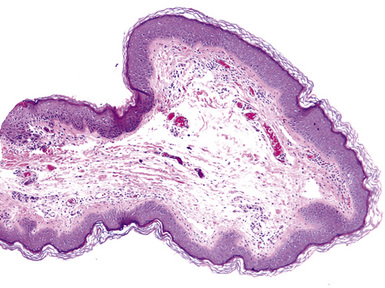

Traumatic neuroma, a discrete injury-related tumefactive lesion of the bronchial mucosa,130,131 may occur spontaneously (e.g., after aspiration of food), or as a result of instrumentation-induced injury of the airway. Histologically, it shows a disorganized proliferation of mucosal nerve bundles, set in a fibrous or fibromyxoid stroma (Fig. 18-29). A mechanistically related process is that of necrotizing sialometaplasia, caused by inflammatory damage to, and pseudocarcinomatous metaplasia of, the bronchial glands.132 Yet another bronchial lesion that has been documented after injury to the lung is the fibroepithelial polyp. It may represent the end result of re-epithelialization of polypoid intraluminal granulation tissue in the airway lumen. When it is ultimately excised, a fibroepithelial polyp shows variable degrees of squamous metaplasia mantling a central fibrovascular polyp, which emanates from the bronchial submucosa (Fig. 18-30).

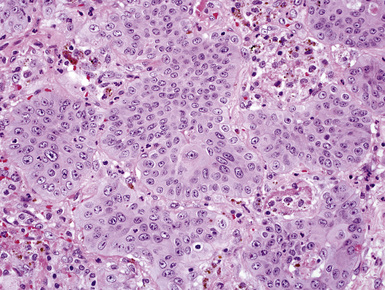

Peribronchiolar Metaplasia (Lambertosis)

As discussed in Chapter 8, peribronchiolar metaplasia (also known as Lambertosis) is a condition wherein metaplastic bronchiolar epithelium extensively colonizes adjacent alveolar spaces.133,134 Occasionally, this process may be so marked as to raise serious concern over the histopathologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Fig. 18-31). When peribronchiolar metaplasia is seen in the setting of emphysema in cigarette smokers, that worry is heightened even further. Nevertheless, the metaplastic elements in peribronchiolar metaplasia are more columnar than those of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, and not as atypical as those of ordinary pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Focal retention of ciliation in the cells of peribronchiolar metaplasia further supports its reactive benign nature, inasmuch as cilia virtually exclude a diagnosis of carcinoma.

Pseudoneoplastic Lesions of the Pleural Surfaces

Pseudoneoplastic lesions of the pleura comprise a relatively small group. Perhaps the most common of them is principally seen by cytopathologists: namely, mesothelial hyperplasia in pleural effusion specimens. Indeed, cytologic simulators of malignancy encompass such a wide variety of entities that they cannot be addressed completely in this text. We will consider selected aspects of this topic, but for a more complete discussion, the reader should consult comprehensive treatises on cytopathology.135–137

Reactive Mesothelial Proliferations

Reactive mesothelial lesions have often been given the descriptive but nebulous label of atypical mesothelial cell proliferation in cytologic practice.138 However, because that terminology implies a possible connection to malignancy, or, at least, premalignancy, we do not advocate its use. Rather, one should simply state that mesothelial cells are hyperplastic or reactive if their morphologic features are clearly benign.139 Such proliferations are associated with a number of underlying pathologic conditions, including cirrhosis, anemia, viral infections, connective tissue diseases, prior radiation, reactions to bronchogenic carcinomas or pleural metastases, recurrent pneumothoraces, and a variety of chronic pleural infections.126,140 An adequate clinical history is obviously necessary to the accurate interpretation of pleural tissue samples. Cytologic features that favor malignancy include the presence of papillae or other architectural complexities, obvious nuclear atypia, necrosis, and pathologic mitotic figures.135,141 There are contrasting criteria for the recognition of reactive or hyperplastic mesothelial lesions.142 They are characterized only by superficial entrapment of mesothelial cell nests in the pleural stroma, an intense inflammatory infiltrate that is densest near the pleural surface, vascular proliferation with few associated spindle cells, an absence of overt nuclear atypia, and a lack of atypical mitoses (Figs. 18-32 and 18-33).

Despite an almost-universal reference to cytologic atypia in the literature on mesothelioma, nuclear aberrations in mesothelioma are often unimpressive. Conversely, cytologic atypia may be striking in reactive mesothelium.143 In general, the cytologic criteria associated with malignant mesothelioma include an elevated nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, irregularity of the nuclear membranes, and coarsely clumped chromatin.141 However, even by morphometric evaluation, conflicting results regarding such features have been reported.144–147

Several attributes of mesothelial cells are potentially shared by both benign and malignant proliferations in cytologic samples. They include cytoplasmic vacuolization, binucleation or multinucleation, and a brush-border pattern that extends over the entire free surface of the cells, correlating with the ultrastructural finding of elongated microvilli.135,141 Reactive cells generally tend to exfoliate singly or in small groups; on the other hand, large formations, including morular structures with “knobby” cellular outlines or papillary structures, raise the likelihood of mesothelioma.141,148 A similar comment applies to uniformly dense mesothelial hypercellularity in an effusion specimen. It should also be understood that the comments just offered apply only to epithelial or biphasic subtypes of malignant mesothelioma, because sarcomatoid variants rarely shed into body cavities. If effusions are present in the latter cases, they usually contain only inflammatory cells and reactive but cytologically benign mesothelial cells.149 The largely hypothetical concept of “mesothelioma in situ” has been introduced for putatively malignant but microscopic lesions limited to the pleural surface.150,151 The distinction of this condition from florid but reactive mesothelial proliferations is unsettled diagnostically.

Immunohistochemistry has limited value in the separation of reactive and malignant mesothelial cells.152 Some analyses have suggested that purely epithelioid mesotheliomas show dense plasmalemmal labeling for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin,153 whereas benign mesothelial cells lack both markers. Nevertheless, these determinants have been shared by both pathologic entities in our experience. Both cell types are consistently negative for carcinoembryonic antigen, tumor-associated glycoprotein-72, and CD15 (all of which are expected in carcinomas), and positive for HBME-1, calretinin, WT1, podoplanin, and keratin 5/6.141,154 Although this panel of reactants is useful in distinguishing adenocarcinoma from mesothelioma, it cannot separate benign and malignant mesothelial lesions.

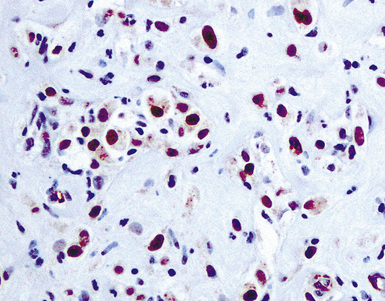

Interest has also arisen regarding the immunostaining of mesothelial lesions for selected gene products that might be correlated with malignancy. In particular, mutant p53 proteins have been assessed in that context, with the expectation that they would be present in malignant mesothelioma but not in benign pleural proliferations.155,156 In fact, when they are immunoreactive for p53 protein, reactive mesothelia usually shows weak nuclear labeling or both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining that should raise suspicion of a spurious result.156 In contrast, mesotheliomas can exhibit convincing and intense nuclear reactivity (Fig. 18-34), but up to 40% are completely nonreactive for p53.155 Although p53 protein immunotyping may provide adjunctive diagnostic information, we believe that it should not be used in isolation. It must be integrated with morphologic findings as well as radiographic details.

More clear-cut criteria are available for the distinction between reactive mesothelium and metastatic carcinoma.142 Carcinomatous effusions often feature a distinctly dimorphic cellular population, although this may be subtle in cases of mammary or gastric cancers.135 Immunohistologic differences have been outlined above. Periodic acid/Schiff stains, performed with and without diastase digestion, label neutral mucins in at least 50% of metastatic adenocarcinomas but not in mesothelial proliferations. Some intracytoplasmic vacuoles in mesothelial cells also contain hyaluronic acid that may stain with the Alcian blue method at pH 2.5; it is digestible with hyaluronidase. Such inclusions may show weak cross-reactivity with mucicarmine stains, potentially causing a mistaken diagnosis of carcinoma. However, spurious mucicarmine staining again disappears after hyaluronidase treatment, unlike the pattern of adenocarcinoma.

Tumefactive Hyaline Pleural Plaques

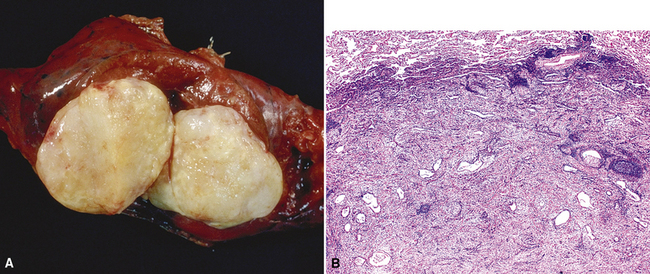

Hyaline pleural plaques (HPPs) are important because of their value as markers of above-background asbestos exposure (Fig. 18-35). Moreover, they occasionally may simulate the radiographic and pathologic appearances of selected mesothelial neoplasms or metastases of malignant tumors in the pleural space.

Many studies have linked asbestos exposure to the emergence of fibrohyaline plaques (Fig. 18-36).157–163 There is also a variable but generally low incidence of these lesions in routine necropsies. Asbestos fibers are absent in the plaques themselves, and, if present, are seen only in the subjacent pulmonary parenchyma. Most patients with bilateral HPP have an increase in commercial-type amphibole asbestos content in the lungs.157–163 The number of fibers is greater than that in the general population but less than the number found in individuals with asbestosis. Unilateral plaques may also be seen in patients with asbestos exposure, but these plaques may also develop as a consequence of chronic pleural irritation of any type. They are commonly associated with infections such as tuberculosis or empyema, chronic or recurrent pleural hemorrhage, and chest wall trauma.162

Figure 18-36 Gross image of fibrohyaline pleural plaques, represented by well-demarcated sessile white-yellow fibrous thickening.

HPPs are most often detected in individuals older than 50 years of age, most commonly in men. Those lesions associated with occupational asbestos exposure show an average latency of 20 years or more from the time of initial dust inhalation.162,163 HPPs characteristically arise in the lower thorax (especially the diaphragm) and preferentially involve the parietal pleura, often with a parallel orientation to the ribs. Much less commonly, they may affect the pericardial surfaces.158 Individuals with HPPs lack symptoms that are directly related to the plaques themselves, and the lesions are regarded as tissue reactions rather than a true disease process. Most associated pulmonary function abnormalities are due to accompanying emphysema or interstitial lung disease.157 Plain films have limited sensitivity for the detection of uncomplicated HPPs, but this statistic increases markedly if the plaques are calcified. The use of CT has greatly improved the ease with which these lesions are recognized.164

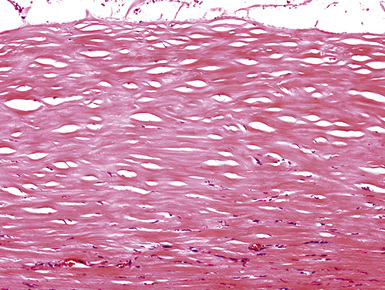

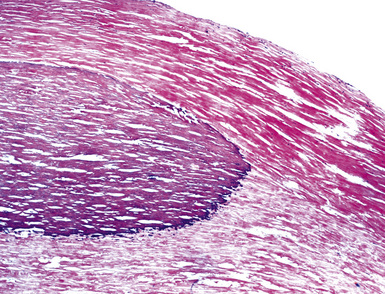

The typical pattern of HPP features hypocellular, dense bundles of hyalinized collagen, often with a “basket weave” arrangement162 (Fig. 18-37). Chronic inflammation may be present in and around the lesion and, in some cases, acute inflammation or fibrin deposition may be seen on the pleural surface. These changes likely reflect the proposed mechanism of formation of the lesion: namely, that of recurrent and organizing pleuritis. Dystrophic calcification is often evident pathologically (Fig. 18-38).

Figure 18-38 Another example of fibrohyaline pleural plaque, containing internal foci of dystrophic calcification.

The main pathologic diagnostic alternative in cases of HPP is that of localized desmoplastic mesothelioma (DM). This tumor shares many of the microscopic characteristics of HPP; both are composed of relatively bland cells that are separated by dense bands of collagen. Nevertheless, there is greater cellularity in DM, at least focally, with areas of storiform growth and a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism.165 Necrosis is also possible in mesothelioma but does not occur in HPP. Involvement of the visceral pleura or diffuse effacement of the pleural space are features usually associated with DM, and they argue against an interpretation of HPP. Adjunctive studies are of very little use in this context. Immunoreactivity for mutant p53 protein is more likely in DM but is not restricted to this lesion.166 Furthermore, a substantial portion of DM cases are completely p53-negative, mirroring the expected immunophenotype of HPP.

Although some solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura may contain keloidal collagen like that seen in HPPs,167 they show much greater cellularity and a dissimilar histologic pattern overall. Furthermore, a solitary fibrous tumor typically presents as a localized, polypoid intrapleural mass rather than a sessile plaque; it is also immunoreactive for CD34, CD99, or bcl-2 protein (unlike HPP) and has no causal relationship to asbestos exposure.

There is no indication for surgical removal of HPPs, except in those rare cases where their radiologic images cause clinical concern over a possible diagnosis of malignancy. Their possible relationship to bronchogenic carcinoma or mesothelioma has been examined, as reviewed elsewhere.168 The plaques themselves appear not to be precursor lesions for malignancies but are simple markers of dust exposure.

Diffuse Pleural Fibrosis

A pathologic process related to HPPs is diffuse pleural fibrosis (DPF; also known as fibrous pleurisy or chronic fibrosing pleuritis). It may be associated with connective tissue disorders, such as lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis, as well as chronic infections and asbestos exposure.169–171 DPF often involves the visceral pleura and may produce apical fibrous “capping” analogous to that seen in association with bullous emphysema. In extreme cases, obliteration of the pleural space may eventuate.

Microscopically, DPF is characterized by the deposition of bland, hypocellular fibrous tissue in the pleura, without the “basket weave” pattern of hyaline plaques (Fig. 18-39). The lesional tissue often demonstrates an increase in vascularity—with vertically oriented capillaries—and may contain scattered foci of chronic inflammation, including plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Fig. 18-40). An associated exudate may be apparent on the luminal pleural surface.

The differential diagnosis centers on the exclusion of DM. The clinicopathologic similarities of DM and DPF are even closer than the likenesses between DM and HPP, because both DM and DPF have the ability to encase the lung in a “rind” of tissue.163 However, DPF lacks the level of cellularity, nuclear atypia, hypovascularity, potential necrosis, and invasive growth of DM. Special studies are generally noncontributory to this diagnostic separation. However, a routine keratin stain may highlight invasion of tumor into pleural fat in cases of DM, and a Verhoeff–van Gieson elastic stain may be illustrative in showing preservation of elastic tissue layering in the pleura (see Fig. 18-38) in DPF, a characteristic that is lost in DM.

1 Koss M.N. Unusual tumor-like conditions of the lung. Adv Pathol Lab Med. 1994;7:123-150.

2 Su L.D., Atayde-Perez A., Sheldon S., et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: cytogenetic evidence supporting clonal origin. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:364-368.

3 Coffin C.M., Dehner L.P., Meis-Kindblom J.M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, inflammatory fibrosarcoma, and related lesions: an historical review with differential diagnostic considerations. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:102-110.

4 Albrecht E. Uber Harmartome. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1904;7:153-157.

5 Takeshima Y., Furukawa K., Inai K. Adenomyomatous hamartoma of the lung. Pathol Int. 2000;50:984-986.

6 McDonald J.R., Harrington S.W., Clagett O.T. Hamartoma (often called chondroma) of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1945;14:128-143.

7 Tomashefski J.F.Jr. Benign endobronchial mesenchymal tumors: their relationship to parenchymal pulmonary hamartomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:531-540.

8 Koutras P., Urschel H.C., Paulson D.L. Hamartoma of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1971;61:768-776.

9 Cosio B.G., Villena V., Echave-Sustaeta J., et al. Endobronchial hamartoma. Chest. 2002;122:202-205.

10 Ge F., Tong F., Li Z. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hamartoma. Chin Med J. 1998;13:61-62.

11 Higashita R., Ichikawa S., Ban T., et al. Coexistence of lung cancer and hamartoma. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;49:258-260.

12 Aggarwal P., Handa R., Wali J.P., et al. Pulmonary hamartoma in a patient with testicular seminoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:552-553.

13 Van Den Bosch J.M.M., Wagenaar S.S., Corrin B., et al. Mesenchymoma of the lung (so-called hamartoma): a review of 154 parenchymal and endobronchial cases. Thorax. 1987;42:790-793.

14 Salminen U.S. Pulmonary hamartoma: a clinical study of 77 cases in a 21 year period and review of the literature. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4:15-18.

15 Hansen C.P., Holtveg H., Francis D., et al. Pulmonary hamartoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:674-678.

16 Wang S.C. Lung hamartoma: a report of 30 cases and review of 477 cases. Chung Hua Wai Ko Tsa Chih. 1992;30:540-542.

17 Tomiyasu M., Yoshino I., Suemitsu R., et al. An intrapulmonary chondromatous hamartoma penetrating the visceral pleura: report of a case. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;8:42-44.

18 Markert E., Gruber-Moesenbacher U., Porubsky C., et al. Lung osteoma—a new benign lung lesion. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:117-120.

19 Xu R., Murray M., Jagirdar J., et al. Placental transmogrification of the lung is a histologic pattern frequently associated with pulmonary fibrochondromatous hamartoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:562-566.

20 Azua-Blanco J., Azua-Romeo J., Ortego J., et al. Cytologic features of pulmonary hamartoma: report of a case diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 2001;45:267-270.

21 Hamper U.M., Khouri N.F., Stitik F.P., et al. Pulmonary hamartoma: diagnosis by transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy. Radiology. 1985;155:15-18.

22 Wood B., Swarbrick N., Frost F. Diagnosis of pulmonary hamartoma by fine needle biopsy. Acta Cytol. 2008;52:412-417.

23 Hughes J.H., Young N.A., Wilbur D.C., et al. Fine-needle aspiration of pulmonary hamartoma: a common source of false-positive diagnoses in the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Nongynecologic Cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:19-22.

24 Incze J.S., Lui P.S. Morphology of the epithelial component of human lung hamartomas. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:411-419.

25 Stone F.J., Churg A.M. The ultrastructure of pulmonary hamartoma. Cancer. 1977;39:1064-1070.

26 Perez-Atayde A.R., Seiler M.W. Pulmonary hamartoma: an ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1984;53:485-492.

27 Johansson M., Dietrich C., Mandahl N., et al. Recombinations of chromosomal bands 6p21 and 14q24 characterize pulmonary hamartomas. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:1236-1241.

28 Fletcher J.A., Pinkus G.S., Donovan K., et al. Clonal rearrangement of chromosome band 6p21 in the mesenchymal component of pulmonary chondroid hamartoma. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6224-6228.

29 Rogalla P., Lemke I., Kazmierczak B., et al. An identical HMGIC-LPP fusion transcript is consistently expressed in pulmonary chondroid hamartomas with t(3;12)(q27-28;q14-15). Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29:363-366.

30 Kazmierczak B., Meyer-Bolte K., Tran K.H., et al. A high frequency of tumors with rearrangements of genes and the HMGI(Y) family in a series of 191 pulmonary chondroid hamartomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;26:125-133.

31 Yilmaz A., Rush D.S., Soslow R.A. Endometrial stromal sarcomas with unusual histologic features: a report of 24 primary and metastatic tumors emphasizing fibroblastic and smooth muscle differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1142-1150.

32 Erasmus J.J., Connolly J.E., McAdams H.P., et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules. Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics. 2000;20:43-58.

33 Chell S.E., Nayar R., De Frias D.V., et al. Metaplastic breast carcinoma metastatic to lung mimicking a primary chondroid lesion: report of a case with cytohistologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2:173-180.

34 Nappi O., Glasner S.D., Swanson P.E., Wick M.R. Biphasic and monophasic sarcomatoid carcinomas of the lung. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:331-340.

35 Landreneau R.J., Hazelrigg S.R., Ferson P.F., et al. Thoracoscopic resection of 85 pulmonary lesions. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:415-420.

36 Nakano M., Fukuda M., Sasayama K., et al. Nd–YAG laser treatment for central airway lesions. Nippon Kyoubu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;30:1007-1015.

37 Pelosi G., Rodriguez J., Viale G., et al. Salivary gland-type tumors with myoepithelial differentiation arising in pulmonary hamartoma: report of 2 cases of a hitherto-unrecognized association. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:375-387.

38 Spencer H. The pulmonary plasma cell/histiocytoma complex. Histopathology. 1984;8:903-916.

39 Matsubara O., Tan-Liu N.S., Kenney R.M., et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the lung: progression from organizing pneumonia to fibrous histiocytoma or to plasma cell granuloma in 32 cases. Hum Pathol. 1988;19:807-814.

40 Pettinato G., Manivel J.C., Rosa N.D., et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (plasma cell granuloma): clinicopathologic study of 20 cases with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:538-546.

41 Cavazza Gelli M.C., Agostini L., et al. Calcified pseudotumor of the pleura: description of a case. Pathologica. 2002;94:201-205.

42 Fetsch J.F., Montgomery E.A., Meis J.M. Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:502-508.

43 Pinkard N.B., Wilson R.W., Lawless N., et al. Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor of the pleura: a report of three cases of a newly described entity involving the pleura. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:189-194.

44 Pomplun S., Goldstraw P., Davies S.E., et al. Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor arising within an inflammatory pseudotumor: evidence of progression from one lesion to the other? Histopathology. 2000;37:380-382.

45 Nascimento A.F., Ruiz R., Hornick J.L., et al. Calcifying fibrous “pseudotumor:” clinicopathologic study of 15 cases and analysis of its relationship to inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10:189-196.

46 Bahadori M., Liebow A.A. Plasma cell granulomas of the lung. Cancer. 1973;31:191-208.

47 Anthony P.P. Inflammatory pseudotumor (plasma cell granuloma) of lung, liver, and other organs. Histopathology. 1993;23:501-503.

48 Ahn J.M., Kim W.S., Yeon K.M., et al. Plasma cell granuloma involving the tracheobronchial angle in a child: a case report. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:204-205.

49 Copin M.C., Gosselin B.H., Ribet M.E. Plasma cell granuloma of the lung: difficulties in diagnosis and prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1477-1482.

50 Mas Estelles F., Andres V., Vallcanera A., et al. Plasma cell granuloma of the lung in childhood: atypical radiologic findings and association with hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:369-372.

51 Monzon C.M., Gilchrist G.S., Burgert E.O., et al. Plasma cell granuloma of the lung in children. Pediatrics. 1982;70:268-274.

52 Tomita T., Dixon A., Watanabe I., et al. Sclerosing vascular variant of plasma cell granuloma. Hum Pathol. 1980;11:197-202.

53 Toccanier M.F., Exquis B., Groebli Y. Granulome plasmocytaire du poumon. Neuf observations avec etude immunohistochemique. Ann Pathol. 1982;2:21-28.

54 Kobashi Y., Fukuda M., Nakata M., et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung: clinicopathological analysis in seven adult patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:461-466.

55 Mohsenifar Z., Bein M.E., Mott L.J.M., et al. Cystic organizing pneumonia with elements of plasma cell granuloma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1979;103:600-601.

56 Cerfolio R.J., Allen M.S., Nascimento A.G., et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:933-936.

57 Agrons G.A., Rosado-de-Cristenson M.L., Kirejczyk W.M., et al. Pulmonary inflammatory pseudotumor: radiologic features. Radiology. 1998;206:511-518.

58 Kawisawa T., Okamoto A. IgG4-related sclerosing disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3948-3955.

59 Shrestha B., Sekiguchi H., Colby T.V., et al. Distinctive pulmonary histopathology with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: report of 6 and 12 cases with similar histopathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1450-1462.

60 Yamamoto H., Yamaguchi H., Aishima S., et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor versus IgG4-related sclerosing disease and inflammatory pseudotumor: a comparative clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1330-1340.

61 Zen Y., Inoue D., Kitao A., et al. IgG4-related lung and pleural disease: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1886-1893.

62 Kojima M., Nakamura N., Itoh H., et al. Presence of immunoglobulin heavy-chain rearrangement in so-called “plasma cell granuloma” of the lung. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:83-87.

63 Park S.H., Choe G.Y., Kim C.W., et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung in a child with Mycoplasma pneumonia. J Korean Med Sci. 1990;5:213-223.

64 Harjula A., Mattila S., Kyoesola K., et al. Plasma cell granuloma of lung and pleura. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;20:119-121.

65 Loo K.T., Seneviratne S., Chan J.K.C. Mycobacterial infection mimicking inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung. Histopathology. 1989;14:217-219.

66 Kim I., Kim W.S., Yeon K.M., et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the lung manifesting as a posterior mediastinal mass. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:467-468.

67 Kuhr H., Svane S. Pulmonary pseudotumor caused by Cryptococcus neoformans. Tidsskr Norweg Laegeforen. 1991;111:3288-3290.

68 Bishopric G.A., D’Agay M.F., Schlemmer B., et al. Pulmonary pseudotumor due to Corynebacterium equi in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Thorax. 1988;43:486-487.

69 Yanagisawa K., Traquina D.N. Inflammatory pseudotumor: an unusual case of recurrent pneumonia in childhood. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;25:261-268.

70 Freschi P., Pocecco M., Carini C., et al. Pseudotumor inflammatorio polmonare post-traumatico: descrizione di un caso. Pediatr Med Chir. 1989;11:93-96.

71 Roikjaer O., Thomsen J.K. Plasmacytoma of the lung. Cancer. 1986;58:2671-2674.

72 Weiss L.M., Yousem S.A., Warnke R.A. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:480-490.

73 Toh H.C., Ang P.T. Primary pulmonary lymphoma—clinical review from a single institution in Singapore. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;27:153-163.

74 Kradin R.L., Mark E.J. Benign lymphoid disorders of the lung with a theory regarding their development. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:857-867.

75 Michal M., Mukensnabl P. Epithelial plasma cell granuloma-like tumors of the lungs: a hitherto-unrecognized tumor. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:311-316.

76 Wick M.R., Ritter J.H., Nappi O. Inflammatory sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: report of three cases and comparison with inflammatory pseudotumors in adult patients. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:1014-1021.

77 Yousem S.A., Hochholzer L. Pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:1-6.

78 Alvarez-Fernandez E., Carretero-Albinana L., Menarguez-Palance J. Sclerosing hemangioma of the lung: an immunohistochemical study of intermediate filaments and endothelial markers. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113:121-124.

79 Illei P.B., Rosai J., Klimstra D.S. Expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 and other markers in sclerosing hemangioma of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1335-1339.

80 Ledet S.C., Brown R.W., Cagle P.T. p53 immunoreactivity in the differentiation of inflammatory pseudotumor from sarcoma involving the lung. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:282-286.

81 Doski J.J., Priebe C.J.Jr, Driessnack M., et al. Corticosteroids in the management of unresected plasma cell granuloma (inflammatory pseudotumor) of the lung. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:1064-1066.

82 Umeki S. A case of plasma cell granuloma which resolved after steroid therapy. Nippon Kyoubu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1993;31:123-126.

83 Imperato J.P., Folkman J., Sagerman R.H., et al. Treatment of plasma cell granuloma of the lung with radiation therapy: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1986;57:2127-2129.

84 Wood C., Nickoloff B.J., Todes-Taylor N.R. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

85 Brandwein M., Choid H.S.H., Strauchen J., et al. Spindle cell reaction to nontuberculous mycobacteriosis in AIDS mimicking a spindle cell neoplasm: evidence for dual histiocytic and fibroblast-like characteristics of the cells. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1990;416:281-286.

86 Chen K.T.K. Mycobacterial spindle cell pseudotumor of lymph nodes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:276-281.

87 Wade H.W. The histoid variety of lepromatous leprosy. Int Lepr. 1963;31:129-142.

88 Triscott J.A., Nappi O., Ferrara G., et al. “Pseudoneoplastic” leprosy. Histoid leprosy revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:297-302.

89 Sekosan M., Cleto M., Senseng C., et al. Spindle cell pseudotumors in the lungs due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a transplant patient. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;18:1065-1068.

90 Umlas J., Federman M., Crawford C., et al. Spindle cell pseudotumor due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): positive staining of mycobacteria for cytoskeletal filaments. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1181-1187.

91 Foucar E., Rosai J., Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

92 Wang C.W., Colby T.V. Histiocytic lesions and proliferations in the lung. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24:162-182.

93 Wright D.H., Richards D.B. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease): report of a case with widespread nodal and extranodal dissemination. Histopathology. 1981;5:697-709.

94 Ratzinger G., Zelger B., Hobling W., et al. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): three unusual manifestations. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:797-800.

95 Lutterbach J., Henne K., Pagenstecher A., et al. Lung cancer and Rosai-Dorfman disease: a clinicopathological study. Strahlenther Onkol. 2003;179:486-492.

96 Chunduri S., Gaitonde S., Ciurea S.O., et al. Pulmonary extramedullary hematopoiesis in patients with myelofibrosis undergoing allgeneic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2008;93:1593-1595.

97 Bowling M.R., Cauthen C.G., Perry C.D., et al. Pulmonary extramedullary hematopoiesis. J Thorac Imaging. 2008;23:138-141.

98 Ogus C., Ozdemir T., Kabaalioglu A. Right hilar mass in a patient with beta-thalassemia major. Respiration. 2001;68:215-216.

99 Kumar P.V., Arasteh M., Musallaye A., et al. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of extramedullary hematopoiesis presenting as a right lung mass. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:698-699.

100 Hsu F.I., Filippa D.A., Castro-Malaspina H., et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis mimicking metastatic lung carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1411-1413.

101 Schwarz C., Bittner R., Kirsch A., et al. A 62 year-old woman with bilateral pleural effusions and pulmonary infiltrates caused by extramedullary hematopoiesis. Respiration. 2009;78:110-113.

102 Nadrous H.F., Krowka M.J., McClure R.F., et al. Agnogenic myeloid metaplasia with pleural extramedullary leukemic transformation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:815-818.

103 Wandall H.H. A study on neoplastic cells in sputum as a contribution to the diagnosis of primary lung cancer. Acta Chir Scand. 1944;91(suppl 93):1-143.

104 Koss L.G. Diagnostic Cytology and Its Histologic Basis, 4th ed., Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1992:849-864.

105 Erozan Y.S. Cytopathologic diagnosis of pulmonary neoplasms in sputum and bronchoscopic specimens. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1986;3:188-195.

106 Jay S.J., Wehr K., Nicholson D.P., et al. Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of pulmonary cytology. Acta Cytol. 1980;24:304-312.

107 Pearson F.G., Thompson D.W., Delarue N.C. Experience with the cytologic detection, localization, and treatment of radiographically undemonstrable bronchial carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1967;54:371-382.

108 Zavala D.C. Diagnostic fiberoptic bronchoscopy: techniques and results of biopsy in 600 patients. Chest. 1975;68:12-19.

109 Truong L.D., Underwood R.D., Greenberg S.D., et al. Diagnosis and typing of lung carcinomas by cytopathologic methods: a review of 108 cases. Acta Cytol. 1985;29:379-384.

110 Berkheiser J.W. Bronchiolar proliferation and metaplasia associated with bronchiectasis, pulmonary infarct, and anthracosis. Cancer. 1959;12:499-508.

111 Berkheiser J.W. Bronchiolar proliferation and metaplasia associated with thromboembolism: a pathological and experimental study. Cancer. 1963;16:205-211.

112 Kawecka M. Cytological evaluation of the sputum in patients with bronchiectasis and the possibility of erroneous diagnosis of carcinoma. Acta Union Int Cancer. 1959;15:469-473.

113 Marchevsky A.M., Nieburgs H.E., Olenko F., et al. Pulmonary tumorlets in cases of “tuberculoma” of the lung with malignant cells in brush biopsy. Acta Cytol. 1982;26:491-494.

114 Johnston W.W., Frable W.J. Cytopathology of the respiratory tract: a review. Am J Pathol. 1976;84:371-424.

115 Ritter J.H., Wick M.R., Reyes A., et al. False-positive interpretations of carcinoma in exfoliative respiratory cytology. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;104:133-140.

116 Policarpio-Nicolas M.L., Wick M.R. False-positive interpretations in respiratory cytopathology: exemplary cases and literature review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:13-19.

117 Saccomanno G., Archer V.E., Saunders R.D., et al. Development of carcinoma of the lung as reflected in exfoliated cells. Cancer. 1974;33:256-270.

118 Koss L.G., Richardson H.I. Some pitfalls of cytological diagnosis of lung cancer. Cancer. 1955;8:937-947.

119 Plamenac P., Nikulin A., Pikula B. Cytologic changes of the respiratory tract in young adults as a consequence of high levels of air pollution exposure. Acta Cytol. 1973;17:241-244.

120 Kern W.H. Cytology of hyperplastic and neoplastic lesions of terminal bronchioles and alveoli. Acta Cytol. 1965;9:372-379.

121 McKee G., Parums D.V. False positive cytodiagnosis in fibrosing alveolitis. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:105-107.

122 Meyer E.C., Liebow A.A. Relationship of interstitial pneumonia and honey-combing and typical epithelial proliferation to cancer of the lung. Cancer. 1965;18:322-351.

123 Williams J.W. Alveolar metaplasia: its relationship to pulmonary fibrosis in industry and development of lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 1957;11:30-42.

124 Johnston W.W. Type II pneumocytes in cytologic specimens: a diagnostic dilemma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;97:608-609.

125 Pei F., Zheng J., Gao Z.F., et al. Lung pathology and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a report of six full autopsies. Chin J Pathol. 2005;34:656-660.

126 Shilo K., Colby T.V., Travis W.D., et al. Exuberant type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia associated with spontaneous pneumothorax: secondary reactive change mimicking adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:352-356.

127 Clayton F. The spectrum and significance of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Pathol Annu. 1988;23(part 2):361-394.

128 Stanley M.W., Henry-Stanley M.J., Gajl-Peczakska K.J., et al. Hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes in acute lung injury. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;97:669-677.

129 Grotte D., Stanley M.W., Swanson P.E., et al. Reactive type II pneumocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from acute respiratory distress syndrome can be mistaken for cells of adenocarcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1990;6:317-322.

130 Miura H., Kato H., Hayata V., et al. Solitary bronchial mucosal neuroma. CHEST. 1989;95:245-247.

131 Rossi G., Marchioni A., Agostini L., et al. Traumatic neuroma of the bronchi: bronchoscopy and histology of a hitherto-unreported lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:640-641.

132 Pagni F., Zarate A.F., Urbanski S.J. Necrotizing sialometaplasia of bronchial mucosa. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:64-65.

133 Couture C., Colby T.V. Histopathology of bronchiolar disorders. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;24:489-498.

134 Fukuoka J., Franks T.J., Colby T.V., et al. Peribronchiolar metaplasia: a common histologic finding in diffuse lung disease and a rare cause of interstitial lung disease: clinicopathologic features of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:948-954.

135 Cibas E.S. Effusions (pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal) and peritoneal washings. In: Atkinson B., editor. Atlas of Diagnostic Cytopathology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2003.

136 Bibbo M. Comprehensive Cytopathology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1991.

137 DeMay R.M. The Art and Science of Cytopathology. Chicago: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press, 1996.

138 Kobayashi T.K., Gotoh T., Nakano K., et al. Atypical mesothelial cells associated with eosinophilic pleural effusions: nuclear DNA content and immunocytochemical staining reaction with epithelial markers. Cytopathology. 1993;4:37-46.

139 Chen C.J., Chang S.C., Tseng H.H. Assessment of immunocytochemical and histochemical staining in the distinction between reactive mesothelial cells and adenocarcinoma in body effusions. Chinese Med J. 1994;54:149-155.

140 Schultenover S.J. Body cavity fluids. In: Ramzi I., editor. Clinical Cytopathology and Aspiration Biopsy. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1990:165-180.

141 Leong A.S.-Y., Stevens M.W., Mukherjee T.M. Malignant mesothelioma: cytologic diagnosis with histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural correlation. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1992;9:141-150.

142 Bedrossian C.W.M., Bonsib S., Moran C. Differential diagnosis between mesothelioma and adenocarcinoma: a multimodal approach based on ultrastructure and immunocytochemistry. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1992;9:91-96.

143 Kutty C.P.K., Remeniuk E., Varkey B. Malignant-appearing cells in pleural effusion due to pancreatitis. Acta Cytol. 1981;25:412-416.

144 Marchevsky A.M., Hauptman E., Gil J., et al. Computerized interactive morphometry as an aid in the diagnosis of pleural effusions. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:131-136.

145 Kwee W.S., Veldhuizen R.W., Alons C.A., et al. Quantitative and qualitative differences between benign and malignant mesothelial cells in pleural fluid. Acta Cytol. 1982;26:401-406.

146 Oberholzer M., Ettlin R., Christen H., et al. The significance of morphometric methods in cytologic diagnostics: differentiation between mesothelial cells, mesothelioma cells, and metastatic adenocarcinoma cells in pleural effusions with special emphasis on chromatin texture. Analyt Cell Pathol. 1991;3:25-42.

147 Ranaldi R., Marinelli F., Barbatelli G., et al. Benign and malignant mesothelial lesions of the pleura: quantitative study. Appl Pathol. 1986;4:55-64.

148 Roberts G.H., Campbell G.H. Exfoliative cytology of diffuse mesothelioma. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25:557-582.

149 Bolen J.W. Tumors of serosal tissue origin. Clin Lab Med. 1987;7:31-50.

150 Whitaker D., Henderson D.W., Shilkin K.B. The concept of mesothelioma in situ: implications for diagnosis and histogenesis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1992;9:151-161.

151 Henderson D.W., Shilkin K.B., Whitaker D. Reactive mesothelial hyperplasia vs. mesothelioma, including mesothelioma in-situ: a brief review. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:397-404.

152 Lee A., Baloch Z.W., Yu G., et al. Mesothelial hyperplasia with reactive atypia: diagnostic pitfalls and role of immunohistochemical studies: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:113-116.

153 Singh H.K., Silverman J.F., Berns L., et al. Significance of epithelial membrane antigen in the workup of problematic serous effusions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;13:3-7.

154 Ferrandez-Izquierdo A., Navarro-Fos S., Gonzalez-Devesa M., et al. Immunocytochemical typification of mesothelial cells in effusions: in vivo and in vitro models. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10:256-262.

155 Cagle P.T., Brown R.W., Lebovitz R.M. p53 immunostaining in the differentiation of reactive processes from malignancy in pleural biopsy specimens. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:443-448.

156 Walts A.E., Said J.W., Koeffler H.P. Is immunoreactivity for p53 useful in distinguishing benign from malignant effusions? Localization of p53 gene product in benign mesothelial and adenocarcinoma cells. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:462-468.

157 Churg A. Asbestos fibers and pleural plaques in a general autopsy population. Am J Pathol. 1982;109:88-96.

158 Fondimare A., Duwoos H., Desbordes J., et al. Plaques fibroyalines calcifiees du foie dans l’asbestose. Nouv Presse Med. 1973;3:893.

159 Hourihane D.O., Lessof L., Richardson P.C. Hyaline and calcified pleural plaques as an index of exposure to asbestos: a study of radiological and pathological features of 100 cases with a consideration of epidemiology. Br Med J. 1966;1:1069-1074.

160 Kishimoto T., Ono T., Okada K., et al. Relationship between numbers of asbestos bodies in autopsy lung and pleural plaques on chest x-ray film. Chest. 1989;95:549-552.

161 Mattson S., Ringqvist T. Pleural plaques and exposure to asbestos. Scand J Respir Dis. 1970;75:1-41.

162 Roberts G.H. The pathology of parietal pleural plaques. J Clin Pathol. 1961:348-353.

163 Warnock M.L., Prescott B.T., Kuwahara T.J. Numbers and types of asbestos fibers in subjects with pleural plaques. Am J Pathol. 1982;109:37-46.

164 Kuhlman J.E., Singha N.K. Complex disease of the pleural space: radiographic and CT evaluation. Radiographics. 1997;17:63-79.

165 Wilson G.E., Hasleton P.S., Chatterjee A.K. Desmoplastic malignant mesothelioma: a review of 17 cases. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:295-298.

166 Mangano E.W., Cagle P.T., Churg A., et al. The diagnosis of desmoplastic malignant mesothelioma and its distinction from fibrous pleurisy: a histologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 31 cases including p53 immunostaining. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:191-199.

167 Moran C.A., Suster S., Koss M.N. The spectrum of histologic growth patterns in benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1992;9:169-180.

168 Wain S.L., Roggli V.L., Foster W.L.Jr. Parietal pleural plaques, asbestos bodies and neoplasia: a clinical, pathologic and roentgenographic correlation of 25 consecutive cases. Chest. 1985;86:707-713.

169 Epler G.R., McCloud T.C., Gaensler E.A. Prevalence and incidence of benign asbestos pleural effusion in a working population. JAMA. 1982;247:617-622.

170 Gibbs A.R., Stephens M., Griffiths D.M., et al. Fiber distribution in the lungs and pleura of subjects with asbestos-related diffuse pleural fibrosis. Br J Ind Med. 1991;48:762-770.

171 Stephens M., Gibbs A.R., Pooley F.D., et al. Asbestos-induced diffuse pleural fibrosis: pathology and mineralogy. Thorax. 1987;42:583-588.