Chapter 25 Proximal, Distal, and Generalized Weakness

Clinical Presentation by Affected Region

Neck, Diaphragm, and Axial Muscles

Neck muscle weakness becomes apparent when the patient must stabilize the head. Riding as a passenger in a car that brakes or accelerates, particularly in emergencies, may be disconcerting for the patient with neck weakness, because the head rocks forward or backward. Similarly, when the patient is stooping or bending forward, weakness of the posterior neck muscles may cause the chin to fall on the chest. A patient with neck-flexion weakness often notices difficulty lifting the head off the pillow in the morning. As neck weakness progresses, patients may develop the dropped head syndrome, in which they no longer can extend the neck, and the chin rests against the chest (Fig. 25.1). This posture leads to several secondary difficulties, especially with vision and swallowing.

Bedside Examination of the Weak Patient

Observation

Weakness of the shoulder muscles causes a characteristic change in posture. Normally the shoulders brace back by means of the tone of the muscles, so the hands are positioned with the thumbs forward when the arms are by the side. As the shoulder muscles lose their tone, the point of the shoulder rotates forward. This forward rotation of the shoulder is associated with a rotation of the arm, so that the backs of the hands now are forward facing. Additionally, the loss of tone causes a rather loose swinging movement of the arms in normal walking. When shoulder weakness is severe, the patient may fling the arms by using a movement of the trunk, rather than lifting the arms in the normal fashion. In the most extreme example, the only way the patient can get the hand above the head on a wall is to use a truncal movement to throw the whole arm upward and forward so the hand rests on the wall, and then to creep the hand up the wall using finger movements. Atrophy of the pectoral muscles leads to the development of a horizontal or upward sloping of the anterior axillary fold. This is especially the case in facioscapulohumeral (FSH) muscular dystrophy. The examiner may observe winging of the scapula, a characteristic finding in weakness of muscles that normally fix the scapula to the thorax (i.e., the serratus anterior, rhomboid, or trapezius). As these muscles become weak, any attempted movement of the arm causes the scapula to rise off the back of the rib cage and protrude like a small wing. The arm and shoulder act as a crane—the boom of the crane is the arm, and the base is the scapula. Obviously, if the base is not fixed, any attempt to use the crane results in the whole structure’s falling over. This is the operative mechanism with attempts to elevate the arm; the scapula simply pops off the back of the chest wall in a characteristic fashion. In the most common type of winging, the entire medial border of the scapula protrudes backward. In some diseases, particularly FSH muscular dystrophy, the inferomedial angle juts out first, and the entire scapula rotates and rides up over the back. This often is associated with a trapezius hump, in which the middle part of the trapezius muscle in the web of the neck mounds over the upper border of the scapula (Fig. 25.2). Note that when examining a slender person or a child, in whom prominent shoulder blades are common, the shoulder configuration returns to normal with forcible use of the arm, as in a push-up.

Muscle Bulk and Deformities

Assessment of muscle bulk looking for atrophy and hypertrophy is an important part of the neuromuscular examination. Prominent muscle wasting usually accompanies neurogenic disorders associated with axonal loss. However, severe wasting also occurs in chronic myopathic conditions. Wasting is best appreciated in the distal hand and foot muscles and around bony prominences. In the arm, wasting of the intrinsic hand muscles produces a characteristic hand posture in which the thumb rotates outward so that it lies in the same plane as that of the fingers (the simian hand), and the interphalangeal joints flex slightly with slight extension of metacarpophalangeal joints (the claw hand). Wasting of the small muscles leaves the bones easily visible through the skin, resulting in the characteristic guttered appearance of the back of the hand. In the foot, one of the easier muscles to inspect is the extensor digitorum brevis, a small muscle on the lateral dorsum of the foot that helps dorsiflex the toes (Fig. 25.3). It often wastes early in neuropathies and anterior horn cell disorders. In myopathic conditions in which proximal muscles are affected more than distal muscles, the extensor digitorum brevis may actually hypertrophy to try to compensate for weakness of the long toe dorsiflexors above it.

Several bony deformities often provide important clues to the presence of neuromuscular conditions. Proximal and axial muscle weakness often leads to scoliosis. Intrinsic foot muscle weakness present from childhood often leads to the characteristic foot deformity of pes cavus, in which the foot is foreshortened with high arches and hammer toes (Fig. 25.4). Pes cavus is a sign that weakness has been present at least since early childhood and implies a genetic disorder in most patients. Likewise, a high-arched palate often develops from chronic neuromuscular weakness present from childhood.

Strength

In an office situation and in many clinical drug trials, manual muscle testing gives perfectly adequate results and is preferable to fixed myometry in young children. The basis is the Medical Research Council grading system, with some modification (Table 25.1). This method is adequate for use in an office situation, particularly if supplemented by the functional evaluation. A scale of 0 to 5 is used, in which 5 indicates normal strength. A grade of 5 indicates that the examiner is certain a muscle is normal and never used to compensate for slightly weak muscles. Muscles that can move the joint against resistance may vary quite widely in strength; grades of 4+, 4, and 4− often are used to indicate differences, particularly between one side of the body and the other. Grade 4 represents a wide range of strength, from slight weakness to moderate weakness, which is a disadvantage. For this reason, the scale has been more useful in following the average strength of many muscles during the course of a disease, rather than the course of a single muscle. Averaging many muscle scores smoothes out the stepwise progression noted in a single muscle. This may demonstrate a steadily progressive decline. A grade of 3+ is assigned when the muscle can move the joint against gravity and can exert a tiny amount of resistance but then collapses under the pressure of the examiner’s hand. It does not denote the phenomenon of sudden give-way, which occurs in conversion disorders and in patients limited by pain. Grade 3 indicates that the muscle can move the joint throughout its full range against gravity, but not against any added resistance. Sometimes, particularly in muscles acting across large joints such as the knee, the muscle is capable of moving the limb partially against gravity but not through the full range of movement. A muscle that cannot extend the knee horizontally when the patient is in a sitting position but can extend the knee to within 30 to 40 degrees of horizontal is graded 3−. Grades 2, 1, and 0 are as defined in Table 25.1.

Table 25.1 The Medical Research Council Scale for Grading Muscle Strength

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No contraction |

| 1 | Flicker or trace of contraction |

| 2 | Active movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Active movement against gravity |

| 4 | Active movement against gravity and resistance |

| 5 | Normal power |

Functional Evaluation of the Weak Patient

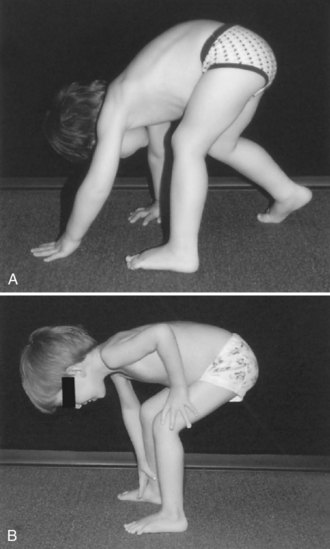

Arising from the Floor

The normal method for arising from the floor depends on the age of the patient. The young child can spring rapidly to the feet without the average observer being able to dissect the movements. The elderly patient may turn to one side, place a hand on the floor, and rise to a standing position with a deliberate slowness. Despite such variability, abnormalities caused by muscle weakness are easily detectable. The patient with hip muscle weakness will turn to one side or the other to put the hand on the floor for support. The degree of turning is proportional to the severity of the weakness. Some patients must turn all the way around until they are in a prone position before they draw their feet under them to begin the standing process. Most people arise to a standing position from a squatting position, but the patient with hip extensor and quadriceps muscle weakness finds it easier to keep the hands on the floor and raise the hips high in the air. This has been termed the butt-first maneuver; the patient forms a triangle with the hips at the apex and the base of support provided by both hands and feet on the floor, and then laboriously rises from this position, usually by pushing on the thighs with both hands to brace the body upward. The progress of recovery or progression of weakness can be documented by noting whether the initial turn is greater than 90 degrees, whether unilateral or bilateral hand support is used on the floor and thighs, whether this support is sustained or transitory, and whether a butt-first maneuver is used. The entire process is known as the Gower maneuver, but it is useful to break it up into its component parts (Fig. 25.5).

Clinical Investigations in Muscular Weakness

Serum Creatine Kinase

The usefulness of measuring the serum CK concentration in the diagnosis of neuromuscular diseases is in differentiating between neurogenic disease, in which normal or mild to moderate elevations of CK may be seen, and myopathies, in which the CK concentration often is markedly increased. Notable exceptions exist. CK concentrations may be elevated as high as 10 times normal in patients with spinal muscular atrophy and occasionally in those with ALS (see Chapter 74). Measurements of serial CK concentrations follow the progress of the disease. Problems have been recognized with both of these uses. Foremost is the determination of the normal level. A survey of 250 hospitals in Ontario, Canada, showed a surprising ignorance of the basic mechanisms involved in the test and the way to derive normal values. Some hospital laboratories were unaware that race, gender, age, and activity level are important in determining normal values. Blood samples obtained from truly normal controls and not from inactive hospital patients not showing overt muscle disease show a higher normal serum CK concentration than would be anticipated. Furthermore, all studies on CK concentration show that gender and race affect values. A log transformation does much to convert this to a normal distribution curve, but even then, the results are not perfect.

Electromyography

The EMG is an operator-sensitive study, and an experienced electromyographer is essential to perform and interpret an EMG correctly. Chapter 32B discusses the principles of EMG. The EMG study may provide much useful information. An initial step in the assessment of the weak patient is to localize the abnormality in the motor unit: neuropathic, myopathic, or neuromuscular junction. Nerve conduction studies and needle electrode examination are particularly useful for identifying neuropathic disorders and localizing the abnormality to anterior horn cells, roots, plexus, or peripheral nerve territories (see Chapters 74 to 76). Repetitive nerve stimulation and single-fiber EMG can aid in elucidating disorders of the neuromuscular junction. Needle electrode examination may help distinguish between the presence of abnormal muscle versus nerve activity, depending on the presence of acute and chronic denervation, myotonia, neuromyotonia, fasciculations, cramps, and myokymia.

Genetic Testing

Chapter 40 covers the details of genetic testing and counseling. Genetic analysis has become a routine part of the clinical investigation of neuromuscular disease and in many situations has supplanted muscle biopsy and other diagnostic tests. This is a distinct advantage to the patient if a blood test can substitute for a muscle biopsy. The use of genetic testing for diagnosis in a specific patient implies that the genetic cause of a specific disease is established, and that intragenic probes are available that allow the determination of whether the gene in question is abnormal. Examples of such abnormalities are deletions in the dystrophin gene, seen in many cases of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and the expansion of the triplet repeat in the myotonic dystrophy gene.

Linkage studies are useful when the gene has a known location, but tests for mutations of the gene itself are not available. The success of such studies depends on having probes that are close to the gene. With use of these closely situated probes, it often can be demonstrated that a person does or does not carry the part of the chromosome on which an involved gene must have occurred in another affected family member. For linkage studies to be successful, a sufficient number of family members both with and without the illness must be available for testing to allow an identification of the segment of the chromosome at fault. Hampering this type of study is the tendency of parts of the chromosome to become detached during meiosis and exchange with parts of another chromosome, a phenomenon known as recombination. The closer the probe is to the actual gene, the less likely recombination is to separate them. Genetic counseling based on linkage studies is less likely to be successful when only one or two patients with the illness and few family members are available. It is difficult to keep up with the mushrooming list of genes known to be associated with neuromuscular diseases, yet maintaining current knowledge is imperative if patients are to be provided with suitable advice. Useful references can be found in the journal, Neuromuscular Disorders, which carries a list of all known neuromuscular genetic abnormalities each month, and on the websites Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/) and GeneTests-GeneClinics (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/GeneTests/).

Differential Diagnosis by Affected Region and Other Manifestations of Weakness

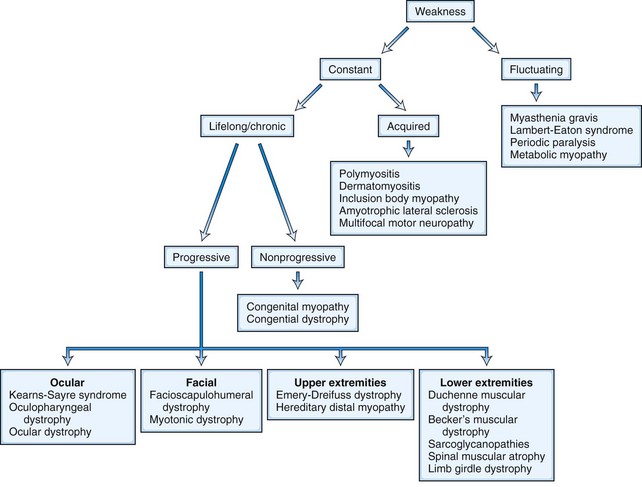

Once the presence of weakness has been established by means of either the history or physical examination, the clinical features may be so characteristic that the diagnosis is obvious. At other times, the cause of the weakness may be less certain. Fig. 25.6 displays an outline of diagnostic considerations based on the characteristics of the weakness, such as whether it is fluctuating or constant. This approach can be used in the differential diagnosis of weakness affecting specific body regions and with other manifestations of weakness, as described next.

Disorders with Distinctive Facial or Bulbar Weakness

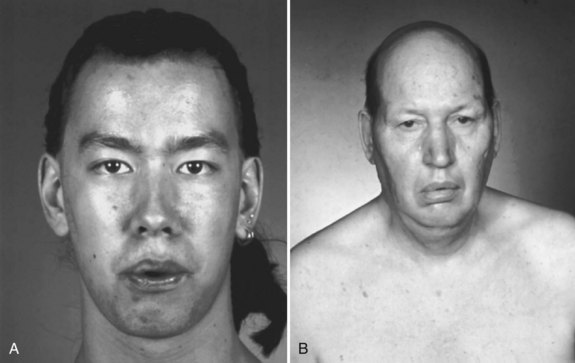

The diagnosis of FSH muscular dystrophy may be delayed until early adult life. Weakness of the face may lead to difficulty with whistling or blowing up balloons and may be severe enough to give the face a smooth, unlined appearance with an abnormal pout to the lips (Fig. 25.7, A). Weakness of the muscles around the shoulders is constant, although the deltoid muscle is surprisingly well preserved and even pseudohypertrophic in its lower portion. When the patient attempts to hold the arms extended in front, winging of the scapula occurs that is quite characteristic. The whole scapula may slide upward on the back of the thorax. The inferomedial border always juts backward, producing the appearance of a triangle at right angles to the back, with the base of the triangle still attached to the thorax. In addition, a discrepancy in power often occurs between the wrist flexors, which are strong, and the wrist extensors, which are weak. Similarly, the plantar flexors may be strong, whereas the dorsiflexors of the ankles are weak. It is common for the weakness to be asymmetrical, with one side much less involved than the other (Fig. 25.8). Inheritance of the disorder is as an autosomal dominant trait, although mild forms of the illness often are asymptomatic.

Myotonic dystrophy type I is a common illness with distinctive features including distal predominance of weakness. Inheritance is as an autosomal dominant trait, but often the family history is negative because patients may be unaware that other family members have the illness. This is due to the phenomenon of anticipation, whereby more severe syndromes appear in successive generations because of the expansion of the trinucleotide repeat. This diagnosis is suggested in any patient with muscular dystrophy and predominantly distal weakness. The neck flexors and temporalis and masseter muscles often are wasted. More characteristic than the distribution of the weakness is the long, thin face with hollowed temples, ptosis, and frontal balding (see Fig. 25.7, B). Percussion myotonia and grip myotonia occur in most patients after the age of 13 years. An EMG study can be diagnostic. Muscle biopsy usually is not necessary but may show characteristic changes. Genetic testing is now preferred to muscle biopsy for diagnosis of the disorder and is almost 100% accurate. The genetic defect is an amplified trinucleotide repeat in the 3′ untranslated region of the myotonin–protein kinase gene on chromosome 19.

A subset of patients with ALS present with isolated bulbar weakness of LMN type (i.e., progressive bulbar palsy) or UMN type (i.e., progressive pseudobulbar palsy). Frequently the condition shows a combination of UMN and LMN involvement. In these patients, dysarthria, dysphagia, and difficulty with secretions are the prominent symptoms. On examination, the tongue often is atrophic and fasciculating (Fig. 25.9), and the jaw and facial reflexes are exaggerated. The voice often is harsh and strained as well as slurred, reflecting the coexistent UMN and LMN dysfunction. In patients with X-linked spinobulbar muscular atrophy (Kennedy disease), bulbofacial muscles also are prominently affected. Patients often have a characteristic finding of chin fasciculations.

Disorders with Prominent Hip-Girdle or Leg Weakness

The inherited muscular dystrophies cause progressive, nonfluctuating weakness. Aside from the inherited distal muscular dystrophies discussed earlier in the chapter, other muscular dystrophies manifest with proximal muscle weakness. Duchenne muscular dystrophy, inherited as an X-linked recessive trait, is associated with an absence of dystrophin. Clinically, the combination of proximal weakness in a male child with hypertrophic calf muscles and contractures of the Achilles tendons gives the clue to the diagnosis. The serum CK concentration is markedly elevated. Although muscle biopsy is diagnostic, genetic testing is now preferred to confirm the diagnosis (see Chapter 40). The clinical features of Becker muscular dystrophy are identical except for later onset and slower progression. Cardiomyopathy also is a feature. Female carriers of the gene usually are free of symptoms but may present with limb-girdle distribution weakness or cardiomyopathy.

The limb-girdle dystrophies constitute a well-accepted diagnostic classification despite their clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Weakness begins in the hips, shoulders, or both and spreads gradually to involve the rest of the limbs and the trunk. Knowledge concerning the genetics of these disorders recently expanded (see Chapter 40), and genetic testing is now available for some limb-girdle dystrophies.

Diagnostic evaluation of limb-girdle muscular dystrophies is rapidly evolving and covered in greater depth in Chapter 79. Genetic testing for dystrophin, sarcoglycans, and other genes may be appropriate before performance of muscle biopsy. If the appropriate genetic tests are uninformative, then muscle biopsy is indicated. The biopsy specimen will show dystrophic changes, separating limb-girdle dystrophy from other (inflammatory) myopathies and from denervating diseases such as SMA. Immunohistochemical analysis of dystrophic muscle may provide a specific diagnosis, but not in all cases. Unfortunately, many patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophies do not receive a specific diagnosis.

Disorders with Fluctuating Weakness

The usual cause of weakness that fluctuates markedly on a day-to-day basis or within a space of several hours is a defect in neuromuscular transmission or a metabolic abnormality (e.g., periodic paralysis), rather than one of the muscular dystrophies. Most neurologists recognize that the cardinal features of MG are ptosis, ophthalmoparesis, dysarthria, dysphagia, and proximal weakness (see Chapter 78). On clinical examination, the hallmark of MG is pathological muscle fatigue. Normal muscles fatigue if exercised sufficiently, but in MG, fatigue occurs with little effort. Failure of neuromuscular transmission may prevent holding the arms in an outstretched position for more than a few seconds or maintenance of sustained upgaze. Frequently the patient is relatively normal in the office, making the diagnosis of myasthenia more difficult; the history and ancillary studies (assay for acetylcholine receptor antibodies, anti-MuSK antibodies, and EMG with repetitive stimulation or single-fiber EMG) must be relied on to establish the diagnosis.

Patients with periodic paralysis note attacks of weakness, typically provoked by rest after exercise (see Chapter 78). Inheritance of the primary periodic paralyses is as an autosomal dominant trait secondary to a sodium or calcium channel defect (see Chapter 64). In the hyperkalemic (sodium channel) form, patients experience weakness that may last from minutes to days; beginning in infancy to early childhood, the provocation is by rest after exercise or potassium ingestion. Potassium levels generally are high during an attack. In the hypokalemic (calcium channel) form, weakness may last hours to days, is quite severe beginning in the early teens, manifests more in males than in females, and the provocation is by rest after exercise or carbohydrate ingestion. Potassium levels generally are low during an attack.

Disorders Exacerbated by Exercise

Fatigue and muscle pain provoked by exercise, the most common complaints in patients presenting to the muscle clinic, often are unexplained. Diagnoses such as fibromyalgia (see Chapter 26) may confound the examination. Biochemical defects are being detected in an increasing number of patients with exercise-induced fatigue and myalgia. The metabolic abnormalities that impede exercise are disorders of carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial function (see Chapter 79). The patient’s history may give some clue to the type of defect.

Disorders of mitochondrial metabolism vary in presentation. In some types, recurrent encephalopathic episodes occur, often noted in early childhood and resembling Reye disease (see Chapter 63). In other types, particular weakness of the extraocular and skeletal muscles is a presenting feature. In still other types, usually affecting young adults, the symptoms are predominantly of exercise intolerance. Defects occur in the electron transport system or cytochrome chain that uncouples oxygen consumption from the useful production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The resulting limit on available ATP causes metabolic pathways to operate at their maximum with even a light exercise load. Resting tachycardia, high lactic acid levels in the blood, excessive sweating, and other indications of hypermetabolism may be noted. This clinical picture may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of hyperthyroidism. It is essential always to measure the serum lactic acid concentration when a mitochondrial myopathy is suspected, even though the level is normal in some patients. In addition to lactate, ammonia and hypoxanthine concentrations also may be elevated.

Lifelong Disorders

Lifelong Nonprogressive Disorders

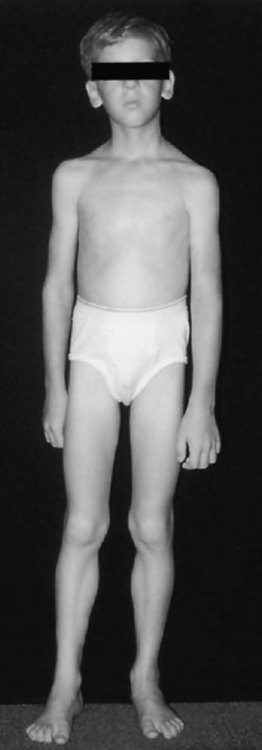

Some patients complain of lifelong weakness that has been relatively unchanged over many years. Almost by definition, such disorders have to start in early childhood. Nonprogression of weakness does not preclude severe weakness. Later-life progression of such weakness may occur as the normal aging process further weakens muscles that have little functional reserve. One major group of such illnesses is the congenital nonprogressive myopathies, including central core disease, nemaline myopathy, and congenital fiber-type disproportion. The typical clinical picture in these diseases is that of a slender dysmorphic patient with diffuse weakness (Fig. 25.10). Other features may include skeletal abnormalities such as high-arched palate, pes cavus, and scoliosis, which are supportive of the presence of weakness in early life. Deep tendon reflexes are depressed or absent. Though unusual, severe respiratory involvement may occur in all these diseases. The less severe (non-X-linked) form of myotubular (centronuclear) myopathy is suggested by findings of ptosis, extraocular muscle weakness, and facial diplegia. Muscle biopsy usually provides a specific morphological diagnosis in the congenital myopathies; specific genetic testing is now available for some congenital myopathies.

Guarantors of Brain. Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th ed. London: W. B. Saunders Ltd.; 2000.

Hogrel J.Y., Laforet P.Y., Ben Yaou R., et al. A non-ischemic forearm exercise test for the screening of patients with exercise intolerance. Neurology. 2001;56:1733-1738.

Jensen T.D., Kazemi-Esfarjani P., Skomorowska E., et al. A forearm exercise screening test for mitochondrial myopathy. Neurology. 2002;58:1533-1538.

Katirji B., Kaminski H.J., Preston D.C., et al. Neuromuscular Disorders in Clinical Practice. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann, 2002.

McArdle W.D., Katch F.I., Katch V.L. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.