48 Prostate disease

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Prostate cancer

Prostatitis

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Epidemiology

BPH is seen in all races although the overall size of the prostate varies from race to race.

Pathophysiology

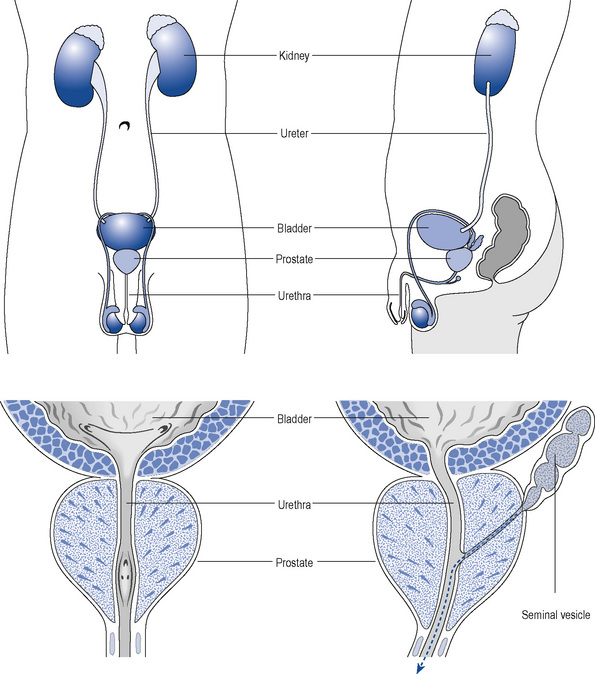

The prostate is a part glandular, part fibromuscular structure about the size of a walnut that surrounds the first part of the male urethra at the base of the bladder (Fig. 48.1). In simple terms, the prostate can be divided into a lobular inner zone encapsulated by an external layer. The inner zone is where benign hypertrophic changes are generally found, whereas most malignant changes originate in the peripheral zone.

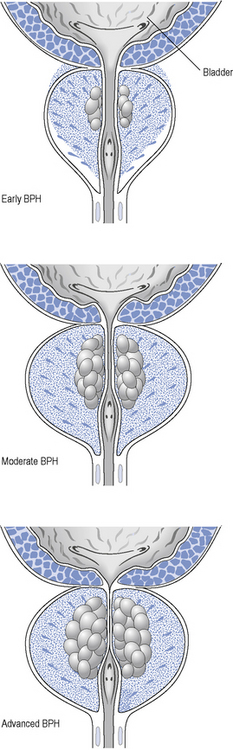

As the prostate enlarges, it can compress the urethra (Fig. 48.2) and this, together with increased adrenergic tone, can lead to bladder outflow obstruction (BOO) and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs). Therefore, the term BPH includes benign prostatic enlargement (BPE), the clinical features associated with urinary obstruction and LUTSs.

Examination and investigations

Treatment

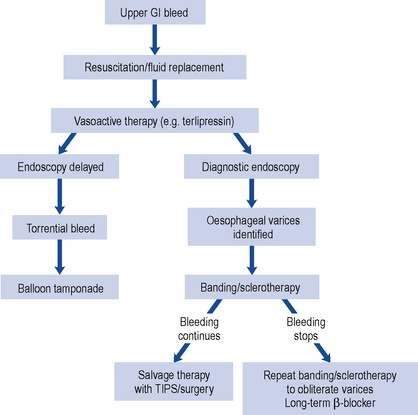

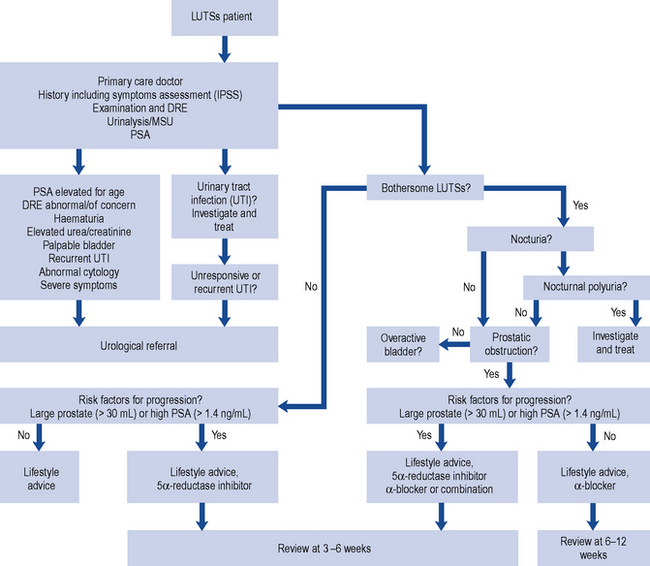

The British Association of Urological Surgeons has published guidelines for the management of BPH in primary care (Speakman et al., 2004), focussing on when urological referral is required and when non-invasive treatment can be initiated (Fig. 48.3).

Fig. 48.3 Algorithm for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs) in males in primary care (from Speakman et al., 2004) (DRE, digital rectal examination; MSU, mid-stream urine sample; PSA, prostate-specific antigen).

Watchful waiting

Men with mild or moderate and not significantly bothersome LUTSs should be offered a trial of watchful waiting. This management strategy does not include any medical or surgical treatment but involves regular active monitoring. In some cases, symptoms remain unchanged for years and no further interventions are necessary since disease progression is minimal. Patients that adopt this modality should be offered education and lifestyle advice (Box 48.1) to manage their urological symptoms together with a review of their medication, particularly diuretics or other medicines known to affect the urinary system.

Therapeutic management

α-Adrenoceptor blocking drugs

Patients with BPH frequently experience erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction. The treatment of BPH should also aim to improve sexual function. However, the effect of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists on male sexual function is variable and influenced by the choice of agent and patient characteristics (Van Dijk et al., 2006).

Doxazosin

Doxazosin has a long half-life of about 22 h, which allows for once-daily dosing. When starting treatment, dose titration is recommended to limit postural hypotension. There would appear to be no significant difference in symptom score regardless of whether the standard or controlled-release preparation is used (Kirby et al., 2001).

Tamsulosin

Tamsulosin is a selective inhibitor of the α1A– and α1B-adrenoceptor. It has an elimination half-life of about 13 h and is available as a prolonged release formulation that allows once-daily dosing. There is no requirement to titrate the dose upward when initiating treatment. Although the side-effect profile of tamsulosin is similar to other α1-adrenoceptor antagonists, it is normally well tolerated (O’Leary, 2001). Intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS) has been reported during cataract surgery in men treated with tamsulosin, as it is highly selective to iris dilator muscle (Chaim et al., 2009). IFIS can lead to complications and poor outcomes during cataract surgery. As a result, it is essential that patients inform their cataract surgeon that they are taking tamsulosin during the pre-operative assessment. It has been recommended to avoid starting treatment and to discontinue treatment with tamsulosin 1–2 weeks before cataract surgery.

Alfuzosin

Alfuzosin displays a higher selectivity for the prostate compared with tamsulosin or doxazosin. It has a half-life of 5 h, but it is available as a once-daily formulation. It has a rapid onset of action and good tolerability (MacDonald and Wilt, 2005). It reduces the overall clinical progression of BPH and it appears to have a sustained beneficial effect on quality of life (Roehrborn, 2006). Alfuzosin has the least effect on ejaculatory function. Alfuzosin should not be co-administered with potent inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 such as itraconazole, ketoconazole and ritonavir, since this can lead to a several fold increase to exposure in alfuzosin.

5α-Reductase inhibitors

The two agents currently available in this group are finasteride and dutasteride. Both have been shown to reduce prostate volume, to improve symptom scores and flow rates, and reduce the incidence of complications such as acute urinary retention (AUR) and the need for surgical intervention to treat BPH (Roehrborn et al., 2000, 2002). Improvements in LUTSs are normally seen after the first 6 months of treatment and are sustained during continuous treatment (Lam et al., 2003).

Combination therapy

The benefits of using a combination of doxazosin and finasteride compared to monotherapy have been demonstrated in over 3000 men (McConnell et al., 2003). Similarly, the combAT trial (Roehrborn et al., 2010) involved nearly 5000 men with moderate to severe symptoms of BPH and prostate enlargement treated with a combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin. This study demonstrated a significant improvement in BPH symptoms over a 4-year period when compared to either agent used alone. The combination was also found to reduce AUR and progression to BPH-related surgery and, although superior to tamsulosin with respect to these complications, combination therapy was not better than dutasteride. Overall, the adverse events associated with combination therapy were few and treatment was well tolerated.

Surgical treatments

Open prostatectomy

Open prostatectomy involves the surgical removal of an enlarged prostate. Typically, an incision is made through the lower abdomen although sometimes the incision is between the rectum and the base of the penis. This procedure is now performed infrequently and restricted to very enlarged prostate glands (larger than 100 mL) and those with large bladder stones or bladder diverticula (Stoevelaar and McDonnell, 2001). Open prostatectomy requires a longer hospital stay than transurethral resection and is associated with a higher incidence of bleeding and other complications.

Patient care

Patients generally seek medical help for BPH because of the impact of symptoms on their quality of life. Most men tolerate a high degree of symptoms and impact on daily activities before they seek help. Table 48.1 lists some common therapeutic problems in the management of BPH. Patients should receive information about the management options available, the investigations that they need to undergo and possible treatment outcomes and adverse effects. Patients receiving drug therapy should receive specific information about their treatment, including potential benefits, timeline of expected outcomes and possible side effects.

Table 48.1 Common therapeutic problems and proposed management strategies in benign prostatic hyperplasia

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Patient taking α-blocker still symptomatic after 2 weeks | Patients should be advised that it may take 2–6 weeks before symptomatic treatment relief is seen |

| Patient taking an α-adrenoceptor blocker complains of cardiovascular adverse effects such as dizziness, syncope, palpitations, tachycardia or angina | These side effects are more likely in elderly patients. They are most common after the first dose and reflect the hypotensive effects of the drugs. They can be reduced by titrating the dose or using more uroselective drugs such as tamsulosin |

| Sexual dysfunction | Decreased libido or impotence can occur in patients taking finasteride and dutasteride. Abnormal ejaculation can be caused by α-blockers. Tamsulosin in particular can cause a dry climax (retrograde ejaculation). Patients should be forewarned when discussing treatment options |

| Patient taking finasteride notices breast enlargement | Unilateral or bilateral gynaecomastia is a frequently reported side effect with finasteride and patients need to be counselled accordingly when discussing treatment options |

| Patient taking finasteride or dutasteride has a sexual partner who is pregnant | Exposure to semen should be avoided as both drugs can cause abnormalities to genitalia in a male fetus. The patient should be advised to use a condom |

There are two websites which produce particularly useful educational material on prostatic disease: the Men’s Health Forum (http://www.menshealthforum.org.uk/) and the Prostate Research Campaign (http://www.prostateuk.org/index.htm).

Prostate cancer

PC is the second most common cancer in the world and the most common form of cancer in men. Incidence varies from country to country with the highest rates in America, Canada and Scandinavia and the lowest rates in China and other Asian countries (Quinn and Babb, 2002; Gronberg, 2003). In the UK, nearly a quarter of all new male cancer diagnoses are of the prostate. The lifetime risk of PC is 1 in 10 in males in the UK.

Prostate-specific antigen

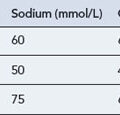

Measurement of PSA is an accurate and clinically useful biochemical marker because it is specific to prostate tissue and produced by the columnar epithelial cells in the prostate gland. Unfortunately, PSA is not cancer specific as any damage to the internal architecture of the prostate can result in release. As a consequence, it is not a useful tool for diagnosing cancer on its own, but it is useful in monitoring the effect of treatment or tumour progression in untreated patients. Generally, PSA is high in PC, but it can sometimes be low in high-grade malignancy. The standard assay for PSA measures total prostate-specific antigen (tPSA) and includes all molecular forms. Age-specific ranges are available (Table 48.2) and help make it a better predictor, but this is only a rough guide as variations occur due to racial difference. There is no threshold for PSA below which PC cannot be found.

| Age | Prostate-specific antigen (ng/mL) |

|---|---|

| 40–49 | ≤ 2.5 |

| 50–59 | ≤ 3.5 |

| 60–69 | ≤ 4.5 |

| >70 | ≤ 6.5 |

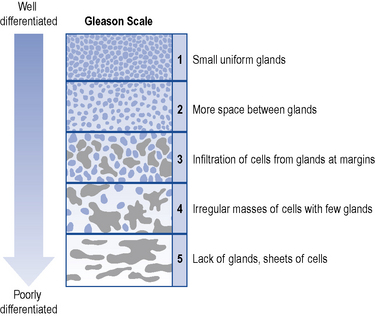

Prostate biopsy

This is a definitive method to detect PC. TRUS guided biopsy will help obtain samples from the peripheral and transitional zones of the prostate and other suspicious areas. The peripheral zone of the prostate is the location where the majority of the PC occurs and the most common location for HGPIN. It is difficult to identify PC from trans-urethral resection of the prostate specimens as not much of it occurs in the transitional zone. In the UK, USA and Europe, the most widely accepted histological grading system, which corresponds to biological malignancy, is based on the Gleason scale (Gleason and Mellinger, 1974). Histological examination of biopsy tissue is undertaken to identify cancer cells and these are scored from 1 to 5 depending on the different pattern of glandular tissue (Fig. 48.4). A score of 1 corresponds to well-differentiated cells, while a score of 5 corresponds to poorly differentiated cells. The higher the score, the more aggressive the cancer. The number for the two most common types of cell in the sample are added together to get a Gleason score. The score ranges from 2 to 10. This is an important prognostic factor as it can help predict the future behaviour of the tumour and determine the treatment required.

Cancer staging

Results from a DRE, biopsy and scan are used to identify the extent of the cancer. The tumour volume, whether there is invasion into or through the capsule, and spread to lymph nodes or bone are all taken into consideration for staging. Staging based on the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) system is a classification accepted worldwide (Epstein et al., 2005). Based on the TNM classification, PC can be classified into localised disease, locally advanced disease and advanced/metastased disease.

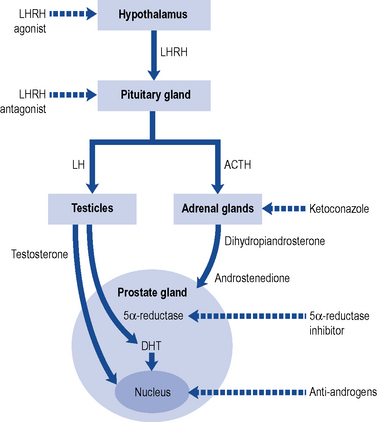

Fig. 48.5 Diagrammatic representation of the site of action of some treatments used in prostate cancer.

Localised prostate cancer

Established treatments with curative intent

Active surveillance

It is difficult to distinguish PC which may not cause any problems to that which may grow and spread aggressively. Curative treatment can improve longevity but has side effects which include impotence and incontinence and can affect the quality of life of the individual. Patients on active surveillance are monitored closely by repeated testing of PSA levels, DRE and biopsy with the intention to make a radical intervention to treat if there is disease progression. A 20-year outcome study following conservative management of localised PC found that the annual mortality rates did not support aggressive treatment (Albertsen et al., 2005). Although active surveillance can spare side effects of treatment without compromising survival, regular biopsies used to monitor the disease can also be uncomfortable and carry a risk of infection. The optimal schedule for measuring PSA and repeating biopsies is unclear.

Minimal invasive procedures

Locally advanced prostate cancer

Hormonal therapy/androgen deprivation therapy

Medical castration

A number of drugs can be used to reduce the levels of testosterone to those achieved by castration.

Anti-androgens

Non-steroidal anti-androgens are used in patients who wish to preserve their quality of life as they do not suppress testosterone and hence preserve libido, physical performance and bone mineral density. The disadvantage of nilutamide, flutamide and bicalutamide is a reduced survival when used as monotherapy because of a gradual rise in testosterone. All three agents have side effects of gynaecomastia, gastro-intestinal upsets, idiopathic hepato-cellular toxicity and haematuria. Bicalutamide has a better safety and tolerability profile compared to nilutamide and flutamide (Inverson, 2002). Some trials show that non-steroidal anti-androgens used in combination with surgical castration or LHRH agonists bring about complete or total androgen blockade by also reducing the production of androgens from the adrenal glands, which normally accounts for 5% of the body’s production, thereby conferring a small survival advantage.

Metastatic prostate cancer

Other palliative treatments

LHRH antagonists

The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on PC recommend the use of LHRH antagonists in patients with metastasis and impending spinal cord compression (Heidenreich et al., 2009).

Bisphosphonates

Skeletal involvement in PC can be disease related or due to androgen depletion therapy. Bisphosphonates are pyrophosphates that inhibit osteoclast activity in bones and hence prevent and treat bone lesions. Pamidronate prevents bone loss but zolendronate not only increases bone mass while on androgen depletion therapy but also reduces skeletal complications in patients with bone metastasis secondary to PC (Saad and Schulman, 2004). Bisphosphonates are also recommended for pain relief when analgesics and palliative radiotherapy to bone have failed. Dental examination needs to be carried out before commencing treatment with a bisphosphonate due to the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in those with a history of dental trauma, infection or surgery.

Treatment is decided after discussing the various options and side effects with the individual. Urinary and sexual function related problems are common side effects of most treatments in PC and need to be discussed in detail with the patient. Emotional factors like depression may also need to be addressed as they can adversely affect the quality of life of the individual. Some of the common problems associated with PC are listed in Table 48.3. Patients can also be referred to http://www.nhs.uk/prostatecancer for facts, information and details of choices available in the diagnosis and treatment of PC. Information on how to cope with the disease and live with PC together with details of various support organisations are available from http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk, whilst http://www.prostate-link.org.uk describes various patient experiences.

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Loss of erectile function after prostatectomy | Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors such as sildenafil have shown efficacy in prevention and help improve chance of spontaneous erection. If medication fails or is contraindicated a vacuum device, intraurethral inserts or penile prosthesis may be used |

| Advanced disease with impending spinal cord compression | Treat with oral dexamethasone and either cyproterone or ketoconazole with external-beam radiotherapy. LHRH agonist treatment is not advisable as the tumour flare up in the initial stage can stimulate tumour growth and exacerbate the condition |

| Bleeding and coagulation disorder | Prostate cancer can cause disseminated intravascular coagulation as a pathological response to the disease. This is a rare condition where small blood clots are formed in the body, disrupt the normal coagulation process and cause bleeding. This can be further complicated if the patient has co-morbidities which require treatment with anti-coagulants. Prompt treatment of the cancer with hormones and in some cases replacement of blood, platelets and clotting factors may be required |

| Hot flushes during androgen deprivation therapy | The hypothalamus is the centre for thermoregulation. Orchiectomy and LHRH agonists inhibit some of the peptides involved in thermoregulation. This increases central adrenergic activity and inappropriate stimulation of thermoregulatory centres, causing peripheral body vasodilatation and hot flushes. Low dose cyproterone acetate (100 mg a day) has been used to suppress hot flushes |

Prostatitis

Epidemiology

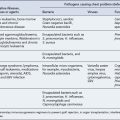

The term prostatitis comprises a range of disorders that have been defined and classified (Table 48.4) by the International Prostatitis Collaborative Network (IPCN) into four categories (Krieger et al., 1999).

Table 48.4 International Prostatitis Collaborative Network (IPCN) classification of prostatitis

| IPCN classification | Comment |

|---|---|

| I. Acute bacterial prostatitis | Acute infection of the prostate |

| II. Chronic bacterial prostatitis | Chronic infection of the prostate |

| III. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome | No evidence of infection |

| A. Inflammatory | Leucocytes in prostatic secretions, post prostate massage urine, or semen |

| B. Non-inflammatory | No evidence of inflammation |

| IV. Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis | Lack of genitourinary symptoms |

Examination and investigations

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion. Typical disorders which must be excluded include the presence of active urethritis, urogenital cancer, urinary tract disease, functionally significant urethral stricture or neurological disease affecting the bladder (Krieger et al., 1999). The main component of this syndrome is the presence of genitourinary pain. After taking a detailed medical history, the evaluation of symptoms can be done using the Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index. Other investigations include a DRE, urinalysis, urine culture and cytology, screening for sexually transmitted diseases, urodynamic studies, prostatic TRUS and serum PSA.

Treatment

The treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis involves long courses (at least 4 weeks) of antibiotics. Fluoroquinolones are used as first-choice agents because of good prostatic penetration, their spectrum of anti-bacterial activity and favourable safety profile. If infective episodes are frequent, patients can be offered prophylactic antibiotics for several months with periodic follow-up to monitor progress (McNaughton-Collins et al., 2007).

Since the aetiology of most cases of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is unknown, management often involves empirical treatment. Despite not being considered to have an infective nature, up to 50% of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome respond to long courses of fluoroquinolones (Nickel et al., 2001), especially men with symptoms of relatively recent onset (a few weeks). Patients with longstanding symptoms refractory to treatment are less likely to benefit from fluoroquinolones. α-Adrenoceptor antagonists are also used alone or in combination with antibiotics in the management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The evidence for efficacy is conflicting but remains an option for patients with persistent symptoms. There are also limited data describing the use of other therapies in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome such as fluoxetine, pollen extract, quercertin, finasteride, mepartricin and pelvic electromagnetic therapy.

Patient care

The British Prostatitis Support Association has a website (http://www.bps-assoc.org.uk) that offers patients information and support.

Albertsen P.C., Hanley J.A., Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2005;293:2095-2101.

Chaim M., Hatch W.V., Fischer H.D., et al. Association between tamsulosin and serious ophthalmic adverse events in older men following cataract surgery. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2009;301:1991-1996.

Epstein J.I., Allsbrook W.C.Jr., Amin M.B., ISUP Grading Committee. The 2005 International Society of Urologic Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.. 2005;29:1228-1242.

Gleason D.F., Mellinger G.T. Prediction of prognosis for prostatic adenocarcinoma by combined histological grading and clinical staging. J. Urol.. 1974;111:58-64.

Gronberg H. Prostate cancer epidemiology. Lancet. 2003;361:859-864.

Heidenreich A., Bolla M., Joniau S., et al. Guidelines on prostate cancer. European Association of Urology. Available at http://www.uroweb.org, 2009.

Inverson P. Antiandrogen monotherapy indications and results. Urology. 2002;60(3 Suppl. 1):64-71.

Kirby R.S., Andersen M., Gratzke P., et al. A combined analysis of double blind trials of the efficacy and tolerability of doxazosin-gastro-intestinal therapeutic system, doxazosin standard and placebo in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Br. J. Urol. Int.. 2001;87:192-200.

Krieger J.N., Nyberg L., Nickel J.C. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 1999;282:236-237.

Lam J.S., Romas N.A., Lowe F.C. Long-term treatment with finasteride in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 10-year follow-up. Urology. 2003;61:354-358.

MacDonald R., Wilt T. Alfuzosin for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms compatible with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review of efficacy and adverse effects. Urology. 2005;66:780-788.

McConnell J.D., Roehrborn C.G., Bautista A.M., et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2003;349:2387-2398.

McNaughton-Collins M., Joyce G.F., Wise M., et al. Prostatitis. Litwin M.S., Saigal C.S., editors. Urologic Diseases in America. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. 2007:9-41. No. 07–5512 http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/statistics/uda/Prostatitis-Chapter01.pdf Available at

Nickel J.C., Downey J., Clark J., et al. Predictors of patient response to antibiotic therapy for the chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. J. Urol.. 2001;165:1539-1544.

O’Leary M. Tamsulosin: current clinical experience. Urology. 2001;58:42-48.

Quinn M., Babb P. International patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part 1: International comparisons. Br. J. Urol. Int.. 2002;90:162-173.

Roehrborn C.G., for the ALTESS Study Group. Alfuzosin 10 mg once daily prevents overall clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia but not acute urinary retention: results of a 2-year placebo-controlled study. Br. J. Urol. Int.. 2006;97:734-741.

Roehrborn C.G., Bruskewitz R., Nickel G.C., et al. Urinary retention in patients with BPH treated with finasteride or placebo over four years. Eur. Urol.. 2000;37:528-536.

Roehrborn C.G., Boyle P.J., Nickel G.C., on behalf of the ARIA3001, ARIA3002 and ARIA3003 study investigators. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor or 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2002;60:434-441.

Roehrborn C.G., Siami P., Barkin J., et al. The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study. Eur. Urol.. 2010;57:123-131.

Saad F., Schulman C.C. Role of bisphosphonates in prostate cancer. Eur. Urol.. 2004;45:1-122.

Speakman M.J., Kirby R.S., Joyce A., et al. Guidelines for the primary care management of male lower urinary tract symptoms. Br. J. Urol. Int.. 2004;93:985-990.

Stoevelaar H.J., McDonnell J. Changing therapeutic regimens in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:131-153.

Van Dijk M.M., de la Rosette J., Michel M.C. Effects of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists on male sexual function. Drugs. 2006;66:287-301.

Batista-Miranda J.E., de la Cruz Diez M., Bertran P.A., et al. Quality of life assessment in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:1079-1090.

Disantostefano R.L., Biddle A.K., Lavelle J.P. An evaluation of the economic costs and patient-related consequences of treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Br. J. Urol. Int.. 2006;97:1007-1016.

Kirby R., Taylor C., editors. Your Guide to Prostate Cancer. London: Hodder Arnold, 2005.

Luzzi G., Street E., Wilson J. Clinical Effectiveness Group. United Kingdom National Guideline for the Management of Prostatitis. British Association of Sexual Health and HIV. 2008. Available at http://www.bashh.org/documents/1844

McVary K.T. Management of Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2004.

Nicholson T.A., Kirby M., Miles A., editors. The Effective Management of Benign Prostatic Disease and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. London: Aesculapius Medical Press, 2000.

Sandhu J.S., Vaughan E.D. Combination therapy for the pharmacological management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:901-912.