Chapter 15 Prostaglandins and Other Eicosanoids

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| DP | D prostanoid |

| EP | E prostanoid |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HPETE | Hydroxyperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| LTs | Leukotrienes |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug |

| PGs | Prostaglandins |

| TXs | Thromboxanes |

Therapeutic Overview

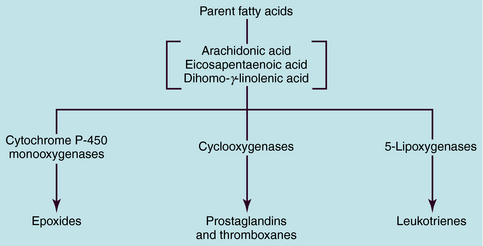

The term eicosanoid is used to represent a large family of endogenous compounds containing oxygenated unsaturated 20-carbon fatty acids and includes the prostaglandins (PGs), thromboxanes (TXs), and leukotrienes (LTs). The name PG was derived from the gland from which these compounds were first isolated, and the LTs derive their name from white blood cells and the inclusion of “trienes” or three conjugated double bonds. The PGs, TXs, and LTs are synthesized as shown schematically in Figure 15-1. Most pathways originate with the parent compound arachidonic acid, a major component of membrane phospholipids. Catalysis by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases produces epoxides, whereas the action of the cyclooxygenases (COXs) produces PGs and TXs, and that of the 5-lipoxygenases (5-LOX) produces LTs.

The PGs, TXs, and LTs exert profound effects on practically all cells and tissues, providing many potential targets for intervention in the treatment of disease. The PGs themselves are used as drugs to mimic effects they would produce if formed endogenously. In addition, many compounds such as the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, see Chapter 36) and corticosteroids (see Chapter 39) produce their effects by inhibiting the formation of the PGs, whereas other compounds block the synthesis of the LTs. New drugs are also being introduced to block PG or LT receptors (see Chapter 16).

| Therapeutic Overview | ||

|---|---|---|

| Drug | Effect | Use |

| Corticosteroids | Block eicosanoid production | Inflammation |

| Prostaglandins | Increased blood flow and oxygenation by vessel relaxation | Neonatal defects |

| Penile erection | ||

| Increased uterine contraction | Induction of labor, abortifacient | |

| Reduced platelet aggregation | Peripheral vascular disease | |

| Reduce intraocular pressure | Glaucoma | |

| Suppress gastric acid secretion | Gastric ulcers | |

| Leukotriene antagonists | Block leukotriene receptor-mediated bronchoconstriction | Asthma |

| Leukotriene synthesis inhibitors | Inhibit lipoxygenase | Asthma |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | Block prostaglandin synthesis | Pain, inflammation |

Mechanisms of Action

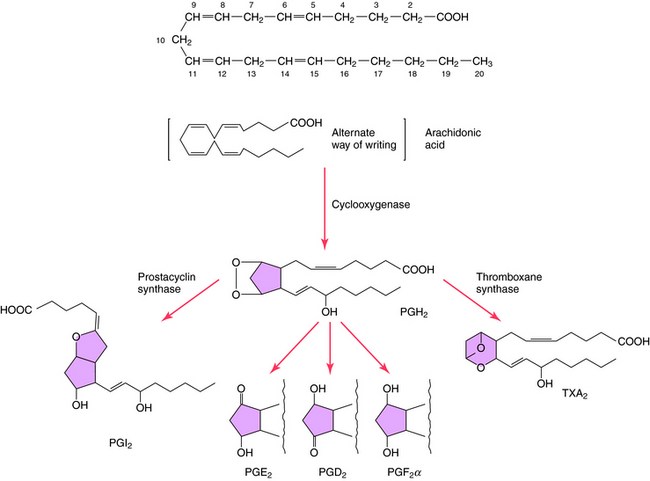

The structures and biosynthesis of PGs and TXs are shown in Figure 15-2. PGs are derived from essential fatty acids, usually arachidonic acid (C20:4). The numbering designation of arachidonic acid, 20:4, indicates 20 carbon atoms and 4 double bonds. The compounds that retain two double bonds in their alkyl side-chains are denoted by the subscript 2, and those that retain three double bonds are denoted by the subscript 3. Arachidonic acid and other fatty acids are cleaved from membrane phospholipids by the action of phospholipase A2 and are metabolized by three different types of enzymes: COXs, lipoxygenases, and cytochrome P450 monooxygenases.

COXs convert arachidonic acid into the PG endoperoxides PGG2 and PGH2. COXs are inhibited by NSAIDS such as aspirin and ibuprofen (see Chapter 36), leading to inhibition of PG and TX formation. Two distinct COXs have been described and have been designated as COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is constitutively expressed, whereas COX-2 is inducible and expressed in response to inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and lipopolysaccharides. Corticosteroids suppress the induction of COX-2 (see Chapter 39), suggesting that control of PG synthesis is involved in the antiinflammatory actions of these compounds. In addition, selective COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib (see Chapter 39) are useful in treating chronic inflammation, because they may cause less gastric disturbance than NSAIDS by allowing formation of cytoprotective PGE2 through COX-1.

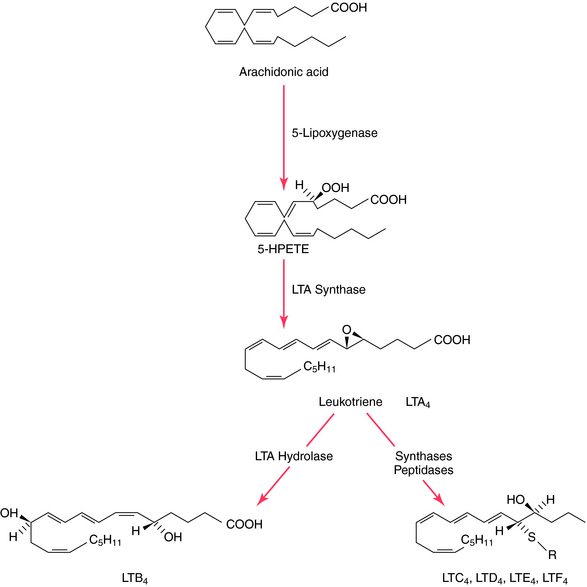

Like the PGs, the LTs are acidic lipids synthesized from essential fatty acids through the action of 5-LOX (Fig. 15-3), a pathway not inhibited by NSAIDs. Three major LOXs have been discovered, which catalyze incorporation of a molecule of O2 into the 5-, 12-, or 15-position of arachidonic acid, forming the corresponding 5-, 12-, or 15-hydroxyperoxyeicosatetraenoic (HPETE) acids. The 5-LOX pathway gives rise to the LTs. LTB4 has potent chemotactic properties for polymorphonuclear leukocytes, promoting adhesion and aggregation, whereas LTC4 and LTD4 are potent constrictors of peripheral lung airways and other vessels, including coronary arteries. The biologic activity of LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 was previously termed “slow-reacting substance.”

PGs are synthesized and secreted in response to diverse stimuli; they are not stored. PGs and TXA2 act primarily as local hormones (autacoids), with their biological activities usually restricted to the cell, tissue, or structure where they are synthesized. Concentrations of PGE2 and PGF2α in arterial blood are very low because of pulmonary degradation, which normally removes more than 90% of these PGs from the venous blood as it passes through the lungs. Not all cells synthesize PGs; for example, there are segments of the nephron that lack COXs or show negligible capacity to transform added arachidonic acid to PGs. In contrast, COX is abundant within the vasculature, although the principal products vary longitudinally along the vasculature and cross-sectionally within the blood vessel wall (e.g., endothelium versus vascular smooth muscle). Within the coronary circulation, the larger blood vessels synthesize principally PGI2, whereas PGE2 predominates in microvessels.

PGs exert their effects by binding to specific cell surface receptors, which have been subdivided pharmacologically with respect to agonist potency and the signal transduction system to which they are coupled. All PG receptors are G-protein coupled receptors (see Chapter 1), which stimulate G-proteins to initiate transmembrane signaling. PGD2 activates D prostanoid (DP) receptors, PGE2 activates E prostanoid (EP) receptors, PGF2α activates F prostanoid (FP) receptors, and PGI2 activates I prostanoid (IP) receptors. PG receptors may stimulate (DP, EP2, EP4, IP) or inhibit (EP2) adenylyl cyclase, or stimulate phospholipase C (EP1, TP), leading to formation of diacylglycerol and inositol trisphosphate and Ca++ mobilization. Many cell types possess several PG receptor subtypes and respond in a variety of ways to PGs. For example, renal tubules possess multiple PG receptors, because low doses of PGE1 inhibit arginine-vasopressin induced H2O reabsorption through Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, whereas high doses of PGE1 cause H2O reabsorption. The tissue-specific functional changes induced by PGE2 acting through four receptor subtypes include vasodilation, bronchodilation, promotion of salt and H2O excretion, and inhibition of lipolysis, glycogenolysis, and fatty acid oxidation. PGI2 produces effects through IP receptors with wide distribution. IP receptors are highly expressed in the vasculature, reflected in the high vasodilator activity of PGI2.

The LTs also act through specific G-protein coupled receptors. LTB4 binds to and activates both subtypes of BLT receptors, BLT1 and BLT2. The cysteinyl LTs bind to and activate two CysLT receptors, designated CysLT1, which binds LTD4 and LTE4, and CysLT2, which binds LTC4. Clinically useful CysLT receptor antagonists include montelukast and zafirlukast. In addition, LT formation can be inhibited by the 5-LOX inhibitor zileuton.* All these agents are useful in the treatment of asthma (see Chapter 16).

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of PGs, LT antagonists, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and related drugs are discussed in Chapters 16, 18, 26, 36 and Chapter 39.

Relationship of Mechanisms of Action to Clinical Response

The dynamic interplay at the platelet-endothelium interface between proaggregatory vasoconstrictor and antiaggregatory vasodilator mediators influences the outcome of arterial insufficiency, thrombosis, and ischemia (see Chapter 26). Key components are the proaggregatory TXA2 and the antiaggregatory PGI2, with interventions that favor PGI2 production and lowering TXA2 formation having the most benefit. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COXs by covalent acetylation. Therapeutic strategies strive to maximize the effect of aspirin on platelet COXs, while sparing as much as possible the effect on endothelial cell COXs. Unlike the endothelium, platelets lack nuclei and cannot synthesize new COX molecules to replace those inactivated by aspirin. Thus a deficient production of TXA2 by platelets cannot be corrected until new platelets form. The effects of aspirin therefore continue for the life of the platelet or more than 10 days. In contrast, after being inhibited, vascular COX can be replaced within a few hours by resynthesis in endothelial cells. Therefore the low-dose aspirin strategy limits the ability of aspirin to enter the systemic circulation to inhibit vascular COX but allows aspirin to act on platelet COX in the portal circulation (from the site of absorption of aspirin to its metabolism by the liver).

PGE1 and PGE2 inhibit basal and stimulated gastric acid secretion and are used for treatment of ulcers, as discussed in Chapter 18. The propensity of NSAIDs to cause gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers is a consequence of eliminating the contribution of PGs to maintain mucosal integrity. Because PGs and their analogs have protective actions on the GI mucosa distinct from their ability to inhibit secretory activity, they are considered cytoprotective (see Chapter 18). COX-2 inhibitors are suggested to have the advantage over NSAIDs in long-term therapy because they do not suppress the cytoprotective effects of PGs and may therefore be less likely to cause ulcers. However, COX-2 inhibitors have serious adverse cardiovascular effects (see Chapter 18).

Inflammatory and Immune Responses

PGs and LTs released in response to infection, and to mechanical, thermal, chemical, and other injuries, participate in inflammatory responses. LTs affect vascular permeability, and LTB4 is a chemoattractant for polymorphonuclear leukocytes. PGE2 and PGI2 enhance edema by increasing blood flow and enhance the action of bradykinin in producing pain. Consequently, COX inhibitors are effective as analgesics and antiinflammatory agents (see Chapter 36).

Elevated concentrations of PGs have been measured in the circulating blood of women during labor or spontaneous abortion, suggesting that initiation and maintenance of uterine contractions may be caused by increased PG synthesis. In fact, labor can be induced by PGE2 given orally; if labor does not occur within 12 hours, oxytocin is substituted. Use of PGE2 to induce labor is accompanied by uterine hypertonus and fetal bradycardia. In contrast to oxytocin, PGs will induce uterine contractions at all stages of pregnancy. Therefore the main use of PGE2 (dinoprostone) and PGF2α (dinoprost) in gynecological practice has been as abortifacients (see Chapter 17).

The lungs produce many PGs and LTs. Mast cells lining the respiratory passages are the likely source of LTs. Overproduction of these substances leads to bronchoconstriction, and they are potential mediators of asthma. PGF2α and TXA2 are also potent bronchoconstrictors, whereas PGE1, PGE2, and PGI2 are potent vasodilators. However, inhaled PGs irritate the airways and are not suitable as antiasthmatic drugs. LT receptor antagonists, including montelukast and zafirlukast, are useful in treating asthma (see Chapter 16).

Pharmacovigilance: Side Effects, Clinical Problems, and Toxicity

Attempts to use authentic PGI2 or its stable analogs to forestall or ameliorate myocardial infarction, cerebral ischemia, and other manifestations of arterial insufficiency are

restricted by the hypotension, headache, and flushing that attend the intravenous infusion of these agents.

James MJ, Cleland LG. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: What went wrong? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:89-94.

Liao Z, Mason KA, Milas L. Cyclooxygenase-2 and its inhibition in cancer: Is there a role? Drugs. 2007;67:821-845.

Lima JJ. Treatment heterogeneity in asthma: Genetics of response to leukotriene modifiers. Mol Diagn Ther. 2007;11:97-104.

Perwez HS, Harris CC. Inflammation and cancer: an ancient link with novel potentials. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(11):2373-2380.

Peters-Golden M, Henderson WRJr. Leukotrienes. N Engl J Med. 2007;57:1841-1854.