Prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors

1. Describe the normal control of prolactin secretion. How is it altered in prolactin-secreting tumors?

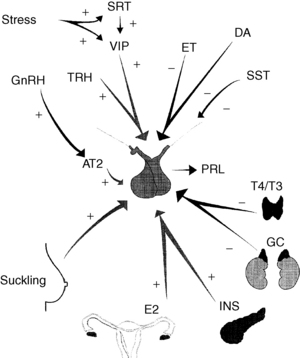

Multiple factors affect prolactin secretion (Fig. 20-1). However, the principal influence on prolactin secretion is tonic inhibition by dopamine input from the hypothalamus. Dopamine interaction with receptors of the D2 subtype on pituitary lactotroph membranes activates the inhibitory G-protein, leading to decreased adenylate cyclase activity and decreased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). In prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas, a monoclonal population of prolactin-producing cells escapes the normal physiologic input of dopamine from the hypothalamus, apparently by acquiring a peripheral blood supply. In almost all cases, responsiveness to a pharmacologic dose of dopamine is maintained.

2. What are the normal levels of serum prolactin? Are they different in men and women? What levels are seen in patients with prolactin-secreting tumors?

The normal serum prolactin level is less than 15 or 30 ng/mL, depending on the laboratory. Women tend to have slightly higher levels than men, probably because of estrogen stimulation of prolactin secretion. In patients with prolactin-secreting tumors, the levels are usually higher than 100 ng/mL but may be as low as 30 to 50 ng/mL if the tumor is small. A level greater than 200 ng/mL is almost always indicative of a prolactin-secreting tumor. Very high prolactin levels may be found to be falsely normal because of the high-dose hook effect of the assay; if clinically indicated, the sample should be assayed again after dilution.

3. What are the physiologic causes of an elevated prolactin level that must be considered in the differential diagnosis of prolactin-secreting tumors? What levels can be reached under these circumstances?

The most important physiologic states in which prolactin is found to be elevated are pregnancy and lactation. During the third trimester of pregnancy, the prolactin level may reach 200 to 300 ng/mL. It then gradually decreases during the first week postpartum, despite continued lactation, but may continue to rise acutely at the time of breastfeeding. Prolactin values are also elevated during sleep, strenuous exercise, stress, and nipple stimulation. In these cases, the elevation is mild, below 50 ng/mL.

4. List the abnormal causes of an elevated serum prolactin value other than a prolactin-secreting tumor, and state the mechanisms underlying the abnormal prolactin production.

TABLE 20-1.

| CAUSES | MECHANISM |

| Pituitary stalk interruption Trauma Surgery Pituitary, hypothalamic, or parasellar tumor Infiltrative disorders of the hypothalamus |

Interference with the hypothalamic-pituitary pathways: Prolactin production increases because the tonic inhibition of prolactin secretion is interrupted; often accompanied by hypopituitarism |

| Pharmacologic agents: Phenothiazines Tricyclic antidepressants Alpha-methyldopa Metoclopramide Cimetidine Estrogens |

Specific interference with dopaminergic input to the pituitary gland |

| Hypothyroidism | Increased thyrotropin-releasing hormone that stimulates prolactin release |

| Renal failure and liver cirrhosis | Decreased metabolic clearance of prolactin; also, increased production in chronic renal failure |

| Intercostal nerve stimulationChest wall lesions Herpes zoster |

Mimicking of the stimulation caused by suckling |

5. What are the typical levels of serum prolactin associated with these causes?

In all these cases, the prolactin value is usually mildly elevated, 30 to 50 ng/mL, and rarely above 100 ng/mL.

6. How does prolactin elevation result in gonadal dysfunction? What are the symptoms associated with gonadal dysfunction?

Elevated prolactin values suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis by interfering with the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in the hypothalamus, resulting in a decrease in circulating levels of estrogen or testosterone. Symptoms include infertility, loss of libido, menstrual irregularity, and amenorrhea in women, and loss of libido and impotence in men.

7. What is galactorrhea? Do most patients with prolactin-secreting tumors present with this symptom?

Galactorrhea is the discharge of milk from the breast not associated with pregnancy or lactation. Although a typical symptom of prolactin-secreting tumors, it may be absent in up to 50% of women, particularly when estrogen levels are very low. Galactorrhea is uncommon in men but may be seen in conjunction with gynecomastia when decreased gonadal function results in a low ratio of testosterone to estrogen.

8. Why do men with prolactin-secreting tumors often present with more advanced disease than women?

The major symptoms of elevated prolactin values in men are decreased libido and impotence. These symptoms may be ignored or attributed to psychological causes. Many years may go by before an evaluation is sought, often when the patient experiences headaches and visual field defects related to the mass effect of the tumor. Women are more likely to seek evaluation early in the disease process, when infertility or menstrual irregularities prompt an evaluation of their hormonal status. Interestingly, studies have suggested that large (≥ 10 mm) and small (< 10 mm) tumors may be biologically different at their onset. It has been found that there is no difference in the prevalence of large tumors between men and women; however, there is a much higher prevalence of small tumors in women. This difference suggests that factors in women, possibly estrogen, may promote the appearance of prolactin-secreting tumors, but when these appear, they may be smaller and less aggressive.

9. What is the imaging technique of choice when a prolactin-secreting tumor is suspected? Why?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary with a contrast agent, such as gadolinium, is the imaging technique of choice for the evaluation of pituitary tumors. In particular, discrimination of small tumors is improved. Computed tomographic (CT) allows better visualization of bone structures, such as the floor of the sella, in cases of large tumors. However, the relationship of the tumor to other soft tissue structures, such as the cavernous sinuses and carotid arteries, is better visualized with MRI. Skull radiographs and tomograms are not helpful.

10. Bone metabolism is altered when prolactin values are elevated. What is the mechanism for this effect? Is it reversible?

The resulting decrease in circulating estrogen or testosterone levels causes a corresponding decrease in osteoblastic bone formation and an increase in osteoclastic bone resorption. Consequently there is a decrease in bone mineral density and progression to osteoporosis. Studies suggest that normalization of prolactin levels restores bone density in most but not all patients, particularly those affected at an early age, before reaching peak bone mass in the third decade of life.

11. If a prolactinoma is left untreated, what is the risk of tumor enlargement?

Many longitudinal studies agree that progression of the disease is rare and occurs at a slow pace. This is particularly true of small prolactin-secreting tumors (< 10 mm), fewer than 5% of which enlarge significantly over 25 years of observation. There is no reliable way to predict which tumors will show progression. Spontaneous resolution, attributed to necrosis, has also been described in some patients, particularly after pregnancy.

12. Is medical treatment available for prolactin-secreting tumors? What is the mode of action?

Medical treatment with dopamine agonists has been available since the early 1980s. The most commonly used drugs are bromocriptine and cabergoline; pergolide and hydergine are also commercially available dopamine agonists, but they are not approved specifically for treatment of prolactin-secreting tumors. Both bromocriptine and cabergoline are highly effective in reducing both prolactin level and tumor size.

13. Describe the mode of action of commonly used drugs.

Dopamine agonists bind to the pituitary-specific D2 dopamine receptors on the cell membrane of prolactin-secreting cells, decreasing intracellular levels of cAMP and Ca2+. This process inhibits the release and synthesis of prolactin. An increase in cellular lysosomal activity causes involution of the rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. The action of dopamine agonists on D1 dopamine receptors in the brain has the side effects nausea and dizziness; dopamine agonists with more D2 specificity, such as cabergoline, are less likely to have these side effects.

14. If a woman with a prolactin-secreting tumor becomes pregnant while undergoing medical treatment, should the treatment be continued? Should she breast-feed her infant?

Even though many studies have found that maternal treatment with dopamine agonists is safe for the fetus, it is recommended that the drug be stopped as soon as pregnancy is diagnosed. The risk of tumor reexpansion is low: less than 5% for small prolactin-secreting tumors and 15% to 35% for large tumors. Assessment of symptoms, particularly headaches, and visual field tests should be performed monthly; any evidence of tumor reexpansion should prompt the reinstitution of treatment. Breast-feeding does not appear to add any significant risk for these patients, but close follow-up should be continued.

15. How long does it take for medical treatment to reduce the serum prolactin level? To reduce the size of the tumor?

The onset of action of dopamine agonists is rapid; because prolactin has a serum half-life of 50 minutes, a decrease in the prolactin level may be noted within 2 hours. However, normalization of prolactin levels may take weeks or months, with the maximal decrease usually seen by 3 months. Tumor size reduction can occur within 48 hours and may be demonstrated by improvement in visual fields when these are affected by the tumor. Tumor shrinkage is usually evident by 3 months; for larger tumors it is recommended that the MRI be performed again at this time. Maximal tumor shrinkage, however, is not usually observed until after at least 12 months of treatment. Another MRI after 1 year of treatment is therefore recommended.

16. How long is medical treatment of prolactin-secreting tumors required? Why?

Lifelong treatment is usually required because prolactin levels rise and tumors reexpand when treatment is interrupted, suggesting that the effect is mostly cytostatic. Later reports, however, suggest that about 20% of cases may be cured after 2 to 5 years of treatment (longer time required for larger tumors), and some evidence suggests that dopamine agonists may have a cytolytic effect.

17. When is surgical removal of a prolactin-secreting tumor indicated?

With the availability of dopamine agonists, surgery has become a secondary choice in the treatment of prolactin-secreting tumors, particularly because the long-term surgical cure rate for large tumors is only 25% to 50%. The principal indications for surgical treatment of a prolactin-secreting tumor are intolerance or resistance to dopamine agonists and acute hemorrhage into the tumor. A cerebrospinal fluid leak due to erosion of the floor of the sella turcica is another indication for surgical debulking and repair.

18. When is radiotherapy indicated to treat a prolactin-secreting tumor?

Radiotherapy has rarely been used because hypopituitarism is a common side effect. This complication is of critical concern, particularly in patients under treatment for infertility. However, radiotherapy may be a useful adjunct in patients who require additional treatment after surgery and who do not tolerate dopamine agonists. Some experts advocate the use of radiotherapy 3 months before attempting pregnancy in women with large tumors to avoid tumor reexpansion during pregnancy. The development of new stereotactic radiosurgical techniques, such as the gamma knife, may improve outcomes and minimize radiation side effects.

Bronstein, MD. Prolactinomas and pregnancy. Pituitary. 2005;8:31–38.

Casanueva, FF, Molitch, ME, Schlechte, JA, et al. Guidelines of the Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006;65:265–273.

Colao, A, Abs, R, Bárcena, DG, et al, Pregnancy outcomes following cabergoline treatment. extended results from a 12-year observational study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:66–71.

Gillam, MP, Molitch, ME, Lombardi, G, et al. Advances in the treatment of prolactinomas. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:485–534.

Molitch, ME. Pharmacologic resistance in prolactinoma patients. Pituitary. 2005;8:43–52.

Schlechte, JA. Long-term management of prolactinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2861–2865.