Chapter 12 Problems in surgical intensive care

12.1 Introduction: what is intensive care?

Intensive care is a relatively new specialty, which has evolved at a considerable pace over the past 30 years. Intensive care medicine involves the care of critically ill patients within a dedicated ward of the hospital, with the ability to continuously monitor and support the various organ systems while allowing the patient to recover. The intensive care unit (ICU) is staffed by dedicated intensive care specialist doctors (intensivists) and specialist intensive care nursing staff. There are medical staff present within the unit at all times and most patients are nursed at a 1:1 ratio of nurses to patients. Other staff such as physiotherapists, dietitians, speech therapists and pharmacists all play an important role within the unit.

12.2 Patient selection

Unplanned admission from the surgical ward

Postoperative deterioration on the surgical ward is not an uncommon problem and patients may require admission to the ICU. Many hospitals nowadays have a rapid response or medical emergency (MET) team to intervene early in the patient’s course and either avert an ICU admission or facilitate rapid transfer to the ICU or operating theatre. This response service may be activated by any member of the medical or nursing staff and calling criteria are based on a set of physiological variables including pulse rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and conscious state.

12.5 Postoperative ICU care

Monitoring — an overview

Monitoring is one of the mainstays of intensive care. It allows for early detection and treatment of problems and to observe and titrate any interventions made. Monitoring may be invasive or noninvasive and includes point of care tests such as arterial blood gases (Table 12.1).

| Cardiovascular monitoring | |

| Noninvasive | Invasive |

| ECG monitoring Noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) monitoring: manual or automatic cuff Repeated transthoracic echocardiography |

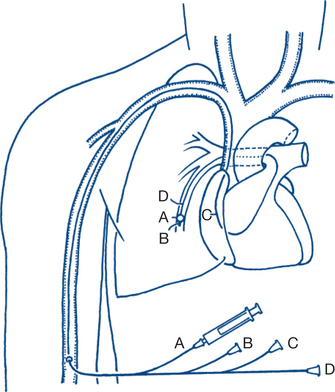

Intra-arterial line — invasive blood pressure monitoring Central venous line — measures central venous pressure (CVP) Pulmonary artery or Swan-Ganz catheter (Fig 12.1) — measures cardiac output (CO), pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and CVP Continuous transoesophageal Doppler wave pulse measurement Continuous/intermittent transoesophageal echocardiography |

| Respiratory monitoring | |

| Noninvasive | Invasive |

| Thoracic impedance measurement of respiratory rate (RR) Saturation probe (plethysmography) End tidal CO2 monitoring Transcutaneous CO2 monitoring Peak flow measurement |

Venous/arterial blood gas monitoring (also allows metabolic monitoring) Measurements made by ventilator via endotracheal tube e.g. flow/volume loops |

| Neurological monitoring | |

| Noninvasive | Invasive |

| Continuous EEG monitoring Bispectral index (BIS) monitoring |

Measurement of intracranial pressure (ICP) |

Intra-arterial and central venous pressure access

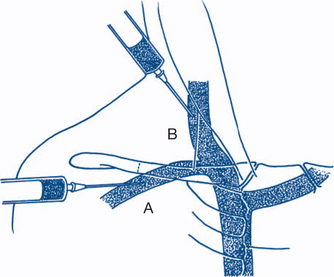

Intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring allows continuous ‘beat to beat’ monitoring of the blood pressure. This is achieved by inserting a catheter into an artery, most commonly using the Seldinger technique of entering a vessel with a needle, inserting a guidewire and then threading the catheter over the guidewire. The catheter is then attached to a pressure transducer and levelled at the phlebostatic axis (the level of the tricuspid valve). Common arterial sites selected are radial (Fig 12.2), femoral and dorsalis pedis. Complications include arterial occlusion, arterial dissection, distal ischaemia and embolisation, infection and bleeding. There are many case reports of limb or digit loss secondary to one of these complications. For this reason, end arteries such as the brachial artery or the femoral artery in young children are less commonly preferred.

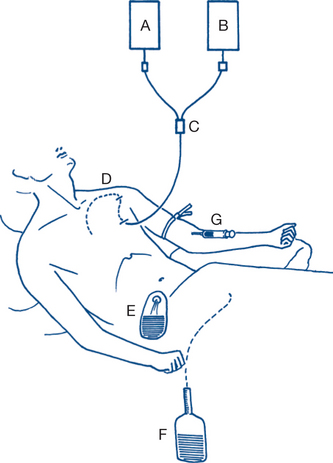

Central venous cannulation allows for measurement of the central venous pressure and for administration of drugs into the central circulation. Central venous catheters may be single or multilumen and are usually inserted via the Seldinger technique. Common sites (Fig 12.3) include the internal jugular, subclavian and femoral veins. These veins are often localised by ultrasound prior to insertion. The catheters are placed so the distal tip lies in the superior vena cava (SVC) for internal jugular and subclavian catheters. Complications relate to either their insertion (pneumothorax, arterial puncture, haemothorax, haematoma) or presence in a central vein (blood stream infection, venous thrombosis/embolisation, venous perforation etc).

Nursing care

The bedside nurse plays a vital role in the overall care of the intensive care patient, being responsible for monitoring the patient’s overall status and vital signs, implementing the physician’s therapeutic plan and attaining physiological targets, administering medications and infusions and, often, adjusting and running the various machines attached to the patient, such as the ventilator or haemodialysis machine. Nursing staff are often in the best position to first notice a change in the patient’s condition and then notify the medical staff. Communication between the two groups is absolutely of paramount importance.

Wound healing in the ICU

Poor wound healing may be due to a number of causes such as:

Nutrition

A number of methods are used to determine the ideal amount of nutrition a patient should receive. One common formula used is the Schofield equation.

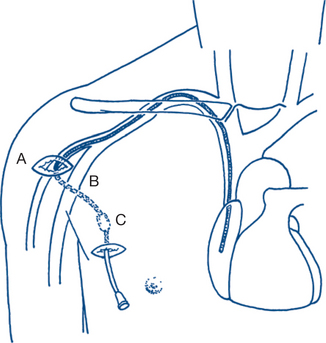

Enteral feeding

Enteral feeding uses the patient’s gastrointestinal tract to provide nutrition and is generally the preferred route in the ICU. This may occur by having the patient eat in the usual manner, but in ICU it usually occurs by administering a prepared feeding formula into the patient via a nasogastric or nasojejunal tube. It may also be administered via a PEG or PEJ (a percutaneous feeding tube into the stomach or small bowel respectively; Fig 12.4). Initially small volumes of food are used, with a gradual escalation to a target volume. Enteral feeding has the advantage of using the patient’s own gastrointestinal tract, is usually relatively noninvasive and confers protective effects on the stomach and intestines. The major drawback is that critically ill patients often have gastrointestinal dysfunction such as gastroparesis or ileus that limits absorption or have had surgery or bowel injury that prohibits the use of the native gut.

Parenteral feeding or total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

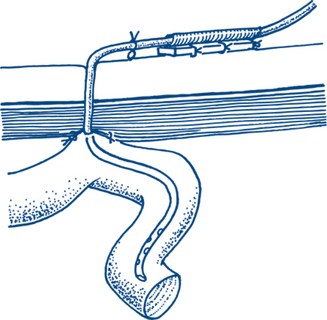

Parenteral feeding involves the infusion of a specially formulated solution into a central vein via a dedicated catheter (CVC or Hickman) (Fig 12.5). It is usually only used in situations where enteral feeding is contraindicated. It has the advantage of having guaranteed delivery of nutrients into the body (Fig 12.6) but has a number of drawbacks. First, it is quite invasive because it requires the placement of a dedicated catheter into a central vein, with all the potential complications that this entails (see above). It has also been associated with an increased risk of blood stream infection via this catheter. Other problems include electrolyte and water balance, hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia.

12.6 Recovery and discharge from the ICU to the surgical ward

While in the ICU the patient is continuously observed and monitored with a view to reducing their levels of organ support. Whenever possible, improvements in isolated organ function or global state should lead to a reduction in the level of ICU intervention. This may manifest as cessation of inotropic or vasoconstrictor drugs, liberation from the ventilator or the removal of intercostal catheters or intracranial pressure monitoring devices. Some supportive therapies, such as renal replacement therapy, may have to be continued for many weeks or even permanently.

12.8 Cardiopulmonary arrest

This chapter will not list algorithms for advanced adult life support — these are freely available from the Australian Resuscitation Council (see: www.resus.org.au). It should be remembered though that certain types of problems leading to arrest may be more common in the ICU patient than the general hospital population. These include massive haemorrhage, tension pneumothorax, pacing failure, tamponade or pseudotamponade in the cardiac or thoracic surgical patient, intracranial catastrophe and various others.

12.9 Common problems in the ICU

Intensive care patients often have very diverse diagnoses and manifestations of disease. Many ICU patients are sedated and on positive pressure ventilation and therefore the telltale signs and symptoms found in the ward patient are absent or disguised. A systematic approach to problems is therefore necessary. The following sections each outline a simple clinical approach to common ICU problems in postoperative surgical patients.

Fever

Fever is a common problem in the postoperative period, as discussed elsewhere in this book (e.g. Ch 11). In the ICU, fever is extremely common and may herald a significant underlying event or problem. The most important condition not to be missed is sepsis (discussed later), which can have many manifestations.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)

SIRS refers to a systemic inflammatory response to a range of insults. The criteria are outlined in Table 12.2.

| Infection | Microbial phenomenon characterised by an inflammatory response to the presence of microorganisms or the invasion of normally sterile host tissue by those organisms. |

| Bacteraemia | The presence of viable bacteria in the blood. |

| Inflammatory response | The systemic inflammatory response to a variety of severe clinical insults. The response is manifested by two or more of the following conditions: (1) temperature >38°C or <36°C; (2) heart rate >90 beats per minute; (3) respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute or PaCO2 <32 mmHg; and (4) white blood cell count >12,000/cu mm, <4,000/cu mm or >10% immature (band) forms. |

| Sepsis | The systemic response to infection, manifested by two or more of the following conditions as a result of infection: (1) temperature >38°C or 36°C; (2) heart rate >90 beats per minutes; (3) respiratory rate >20 breaths per minute or PaCO2 <32 mmHg; and white blood cell count >12,000/cu mm, <4,000/cu mm or >10% immature (band) forms. |

| Severe sepsis | Sepsis associated with organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion or hypotension. Hypoperfusion and perfusion abnormalities may include, but are not limited to, lactic acidosis, oliguria or an acute alteration in mental status. |

| Septic shock | Sepsis-induced with hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation along with the presence of perfusion abnormalities that may include, but are not limited to, lactic acidosis, oliguria or an acute alteration in mental status. Patients who are receiving inotropic or vasopressor agents may not be hypotensive at the time that perfusion abnormalities are measured. |

| Sepsis-induced hypotension | A systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg or a reduction of ≤ 40 mmHg from baseline in the absence of other causes of hypotension. |

| Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) | Presence of altered organ function in an acutely ill patient such that homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention. |

Source: Bone et al 1992 Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest; 101, 1644–1655

Sepsis

Sepsis refers to a SIRS state caused by an infectious process such as bacteraemia, pneumonia or faecal peritonitis. The criteria for sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock are outlined in Table 12.2.

Sepsis is an extremely common reason for admission to the ICU and has a high mortality rate. It has deleterious effects on all organ systems and its manifestations may initially be nonspecific. As a result it may not initially be recognised, as the presentation of tachypnoea or confusion in seeming isolation may initially suggest another diagnosis. Sepsis may occur in the preoperative or postoperative period and requires aggressive resuscitation. Source control is extremely important, with early and aggressive surgical treatment required for peritonitis, abscesses etc. Obstruction of the biliary and renal tracts should be relieved promptly. Antibiotics alone are frequently insufficient treatment and should not replace definitive surgery. Adjunctive therapies include steroids (stress dose hydrocortisone) and, occasionally, vasopressin in refractory shock. Other therapies such as activated protein C are occasionally used.

Hypotension and shock

Hypotension in the ICU is difficult to define, as the desired mean arterial pressure (MAP) may vary from patient to patient and condition to condition. A commonly used aim is a MAP of 70 or greater. Shock refers to a constellation of signs of inadequate tissue oxygenation, including acidosis, oliguria and organ dysfunction.

Causes of hypotension and shock vary and a variety of grouping classifications have been developed. A simple way of approaching the problem is listed in Table 12.3 with a couple of examples shown.

| Hypovolaemia | Bleeding/fluid losses |

| Cardiogenic | Acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, brady/tachyarrythmia |

| Obstructive | Cardiac tamponade, pneumothorax, massive pulmonary embolism |

| Distributive | Sepsis, anaphylaxis, spinal cord injury |

| Mixed aetiology | Some drug overdoses, amniotic fluid embolism, total spinal anaesthesia etc. |

Inotropes and vasopressors

Hypertension

A very common cause of hypertension in the ICU patient is undertreated pain in the sedated patient. This should always be excluded, as should the fortunately rare occurrence of inadequate sedation in the presence of muscle relaxation and noxious stimuli. Occasionally, other rare causes of hypertension are diagnosed in the surgical ICU, for example, phaeochromocytoma.

Metabolic and electrolyte disturbances

Acid–base disorders

Acid–base disturbance is very common in the ICU and is an involved and complicated topic. In extremely simplistic terms, acidaemia/osis and alkalaemia/osis are defined in the following table Table 12.4.

| Acidaemia | Alkalaemia |

|---|---|

| pH <7.35 Metabolic acidosis if bicarbonate low |

pH >7.45 Metabolic alkalosis if bicarbonate high |

| Respiratory acidosis if CO2 high | Respiratory alkalosis if CO2 low |

Metabolic acidosis

First, the anion gap should be calculated:

Normal is considered 14–17. A raised anion gap indicates the presence of an unmeasured anion such as lactate. Some causes appear in Table 12.5.

| Normal anion gap | Raised anion gap |

|---|---|

| GI bicarbonate loss | Lactate |

| Renal bicarbonate loss | Renal injury |

| Excess chloride administration | Ketones |

| Toxins e.g. aspirin, alcohols |

Metabolic alkalosis

Common causes in the ICU include diuretic administration and large nasogastric losses.

Sodium and water (disorders of tonicity)

Hypo- or hypernatremia is a common problem in the ICU. Although there is a tendency to view these conditions as disorders of sodium balance, they are in fact disorders of water balance.

Disorders of potassium

Hyper- and hypokalaemia are both very common in the ICU. Hypokalaemia may result in atrial and ventricular dysrhythmias and sudden death, while hyperkalaemia if left untreated will result in a so-called sine wave ECG and asystole. Disorders of potassium, a largely intracellular cation, fall into two main categories. These are problems of total body depletion or overload or problems of potassium distribution between the intra- and extracellular compartments. Table 12.6 shows some causes of potassium imbalance.

| Hypokalaemia | Hyperkalaemia |

|---|---|

| Urinary losses e.g. diuretics | Renal injury |

| Alkalosis | Acidosis |

| Drugs e.g. salbutamol | Potassium administration |

| Nasogastric losses/vomiting | |

| Anorexia/bulimia (poor diet/vomiting) |

Oliguria/renal dysfunction and renal replacement

Decreased urine output is very common in the ICU. This is partly physiological, as major surgery is a powerful stimulus for antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release. However, the ICU patient is extremely susceptible to renal injury from a variety of mechanisms and close monitoring is vital.

Multiple factors contribute to renal injury/dysfunction in the ICU. Patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction are at extremely high risk. Urological causes are discussed in Chapter 9 but urinary tract obstruction secondary to prostatic hypertrophy, calculi or extrinsic ureteric compression (cancer, haematoma etc.) should always be excluded. Acute abdominal compartment syndrome (where raised intra-abdominal pressure causes renal compression and reduced renal blood flow) should also be ruled out. Other causes are listed in Box 12.1.

Box 12.1

Causes of renal dysfunction/oliguria in the ICU

Acute tubular necrosis secondary to volume depletion/hypotension of any cause

Abdominal compartment syndrome

Nephrotoxic drugs — e.g. gentamicin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, ACE inhibitors

Interstitial nephritis secondary to drugs e.g. penicillins

Renovascular causes: embolic events, renal vein thrombosis

Hepatic failure (hepatorenal syndrome)

Hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction

Gut dysfunction in the critically ill surgical patient is extremely common, even in those patients who have not had abdominal surgery. It may manifest as prolonged ileus, gastroparesis, failure to absorb enteral nutrition, colonic pseudo-obstruction, volvulus or severe constipation. Common reasons include drugs (opiates, barbiturates), metabolic/electrolyte disturbance and prolonged immobility. Treatment involves correction of metabolic disturbance, decrease in sedation if possible and the use of prokinetics for gastric mobility. Occasionally, surgery, colonoscopic decompression or neostigmine is required.

Neurological dysfunction

Neurosurgical causes of neurological dysfunction are discussed elsewhere in this book (Chs 2 and 5). Neurological dysfunction in the non-neurosurgical ICU patient is common and may be either central (Box 12.2) or peripheral.

Box 12.2

Central causes of neurological dysfunction

Haematological dysfunction and haemorrhage

Haematological dysfunction in the ICU may take several forms:

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)

This describes a clinical picture of multiple organ/organ system dysfunction that may be the result of any number of causes. Examples of conditions that may lead to MODS are sepsis, post cardiac arrest, burns and severe and multiple trauma. When the insult leads to frank organ failure, the term multisystem organ failure (MOF) is sometimes used. Although potentially recoverable in many cases, MODS often heralds a bleak prognosis that is related to the number of organ systems failing.