CHAPTER 8 Principles of surgery and management of intraoperative complications

Opening and Closing the Abdomen

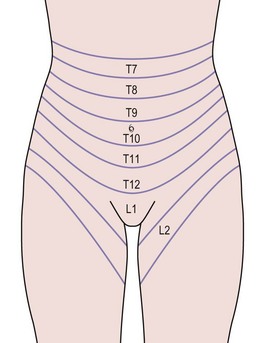

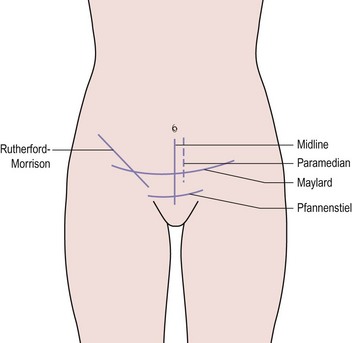

The layers of the anterior abdominal wall include skin, subcutaneous fat, rectus sheath and oblique abdominal muscles, transversalis fascia and peritoneum. Within these structures lie segmental arteries, veins and nerves that supply the dermatomes and myotomes, and also the epigastric vessels (Figure 8.1). Abdominal incisions have been developed that preserve function as well as possible and which heal rapidly with good strength. Commonly used incisions are shown in Figure 8.2.

It should not be forgotten that inappropriate wound closure technique can increase the risk of pulmonary complications and death (Niggebrugge et al 1999). While some surgeons prefer to use electrocautery rather than a cold scalpel to open the wound, there seems to be no difference in the early or late complications in midline incisions (Franchi et al 2001).

Incisions

The vertical midline incision avoids all major nerves, vessels and muscles by dividing the rectus sheath. It gives good access to the whole of the abdomen except the subdiaphragmatic areas, and is a very fast incision to make. Its principal drawback is that it heals slowly and suffers from a high incidence of wound dehiscence and incisional hernia. The development of improved sutures and technique has dramatically reduced these complications. A midline incision should always be closed using the ‘mass closure’ technique. This involves 1-cm-deep bites of the rectus muscle and peritoneum in a continuous closure, with sutures placed 1 cm apart. The suture material used does not affect the rates of dehiscence or infection, but incisional hernia is more common if braided absorbable material is used (Rucinski et al 2001). The same meta-analysis showed that incision pain and suture sinus formation are more common after non-absorbable material is inserted. Absorbable monofilament used in a continuous mass closure gave the best results.

The Maylard incision involves dividing all layers in the line of the skin incision and also divides the inferior epigastric vessels. The rectus sheath is not separated from the muscle and closure is in layers, leaving the muscle to be drawn together by the sheath. This incision provides improved access to the pelvic side wall when compared with the Pfannenstiel incision, and is useful for oncological surgery. Many centres now use this incision or a Pfannenstiel incision for radical hysterectomy (Orr et al 1995, Scribner et al 2001).

Drains

Drains are used either therapeutically, to remove pus, infected material and products from an abscess, or to prevent accumulation of blood, pus, urine, lymph, bile or intestinal secretions. There is little evidence to support the use of prophylactic drains. In abdominal incisions, drains have been used in an attempt to reduce the incidence of haematoma and wound infection. Unfortunately, they tend to introduce organisms into an otherwise clean area and increase the incidence of wound infection (Cruise and Foord 1973). In addition, pelvic drains do not reduce infection following radical pelvic surgery (Orr et al 1987). Careful attention to haemostasis is preferable and drains should be avoided in most closures.

Closure of peritoneum

This practice has been questioned recently. Research in animal models has suggested that closure of the peritoneum increases rather than decreases peritoneal adhesions. Human studies support this finding, showing that closure of the pelvic peritoneum does not reduce the incidence of postoperative adhesions or obstruction (Table 8.1; Tulandi et al 1988). The peritoneum spreads rapidly across any raw areas left after surgery, although devascularized tissue, such as pedicles, are a focus for adhesion formation. Practice still varies with regard to peritoneal closure, although it probably results in increased adhesion formation (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1998). However, if a suction drain is used in the wound, the peritoneum must be closed to avoid drawing the bowel into the wound.

Table 8.1 The effect of peritoneal closure on wound infection and adhesion formation.

| Closed (%) | Not Closed (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wound infection | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| Adhesions | 22.2 | 15.8 |

| Obstruction | 1.6 | 0 |

Source: From Tulandi T, Hum HS, Gelfand MM 1988 Closure of laparotomy incisions with or without peritoneal suturing and second look laparoscopy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 158:536, with permission of Elsevier.

Ureteric Damage

The ureter at the pelvic brim and ovarian fossa

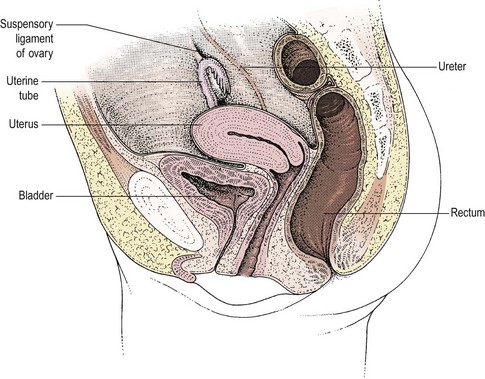

At the pelvic brim, the infundibulopelvic ligament with the ovarian vessels also crosses the iliac vascular bundle, usually 1–2 cm distal to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and the ureter (Figure 8.3). At this point, the ureter and the ovarian vessels are running in parallel in a similar plane and may be confused if care is not taken. Occasionally, the ureter may be duplex. Where the ureter runs lateral to the ovary, it will almost inevitably be associated with any inflammatory or malignant mass. Happily, it will lie on the lateral aspect of the mass where it can be identified and dissected free, usually without difficulty, although in patients with endometriosis, the ureter may be fixed in dense fibrosis.

The lower ureter

The third position where the ureter is at risk is in the ureteric tunnel, where the ureter crosses beneath the uterine artery but superior to the cardinal ligament and approximately 1–1.5 cm lateral to the angle of the vagina (Figure 8.4). It is possible to palpate the ureter in this position by gripping the paracervical tissue between one finger in the pouch of Douglas and the thumb placed laterally in front of the uterine pedicle. The ureter, which is felt as a firm cord running across the cardinal ligament, is surprisingly far lateral to the cervix if the bladder has been properly reflected and the anatomy is normal. However, adhesions, fibrosis or inadequate dissection may disrupt these relationships, causing the ureter to remain fixed near the lateral margin of the cervix.

Repairing ureteric damage

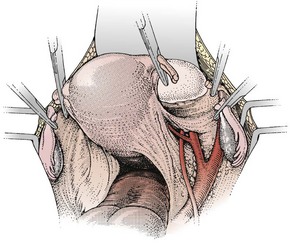

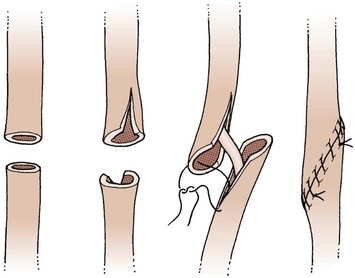

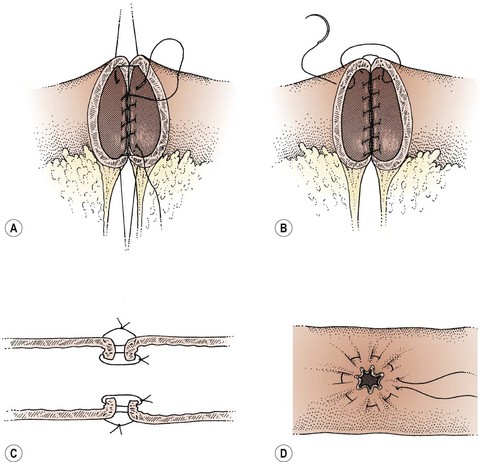

Repair of the ureter is technically demanding and may lead to long-term complications. It is not appropriate for a gynaecologist without urological training or extensive urological experience to undertake this. In principle, an end-to-end anastomosis can be performed for ureteric damage at the pelvic brim or above. The ureter is mobilized so that the ends can be brought together without tension. They are spatulated and the anastomosis performed using fine interrupted sutures over a Silastic stent (Figure 8.5). This is removed several weeks later. An alternative for damage at this level is to perform a uretero-ureteric anastomosis.

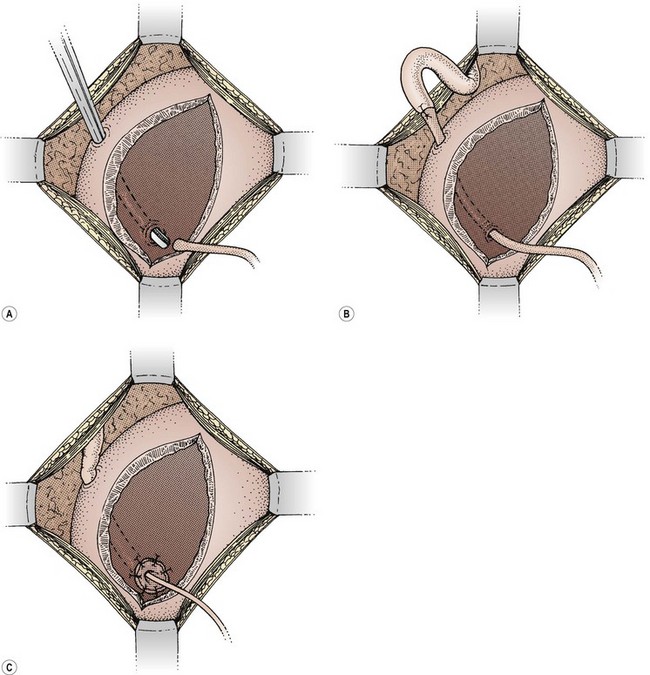

If the damage has occurred at the level of the ureteric tunnel or lower, the safest method of repair is to reimplant the ureter into the bladder. The bladder is opened between stay sutures. A submucosal tunnel is fashioned, taking care to avoid the other ureter. The distal end of the ureter is brought through the tunnel and, after spatulating the end, is sutured to the bladder mucosa. A couple of sutures into the serosal surface anchor the ureter to the outer layer of the bladder (Figure 8.6).

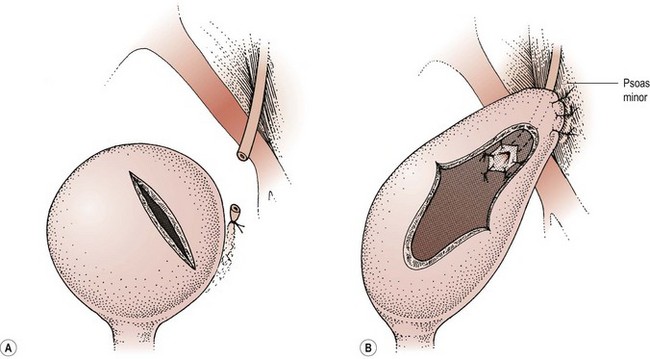

When damage has occurred higher on the pelvic side wall, the bladder can be elevated to the cut end of the ureter to allow reimplantation without tension, using either a psoas hitch or a Boari flap. In the former, an appropriate part of the bladder is elevated towards the end of the ureter. To facilitate this, the cystotomy is performed across the direction of elevation and is closed in the opposite direction to elongate the bladder. In addition, the contralateral superior vesical pedicle may be divided. The ureter is reimplanted as described previously and the bladder is fixed to the psoas muscle to relieve any tension. This technique will allow a ureter divided at any level in the pelvis up to the pelvic brim to be safely reimplanted (Figure 8.7).

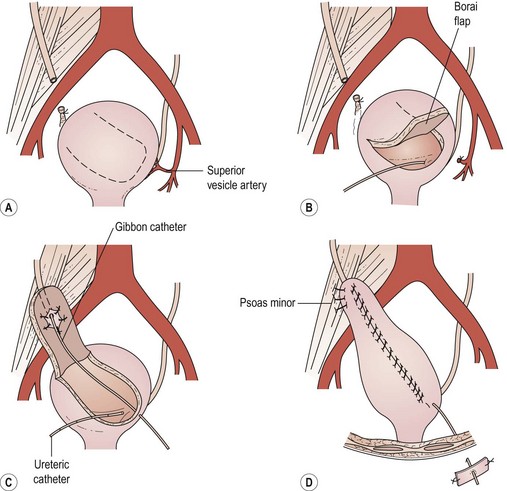

The Boari flap is an alternative to the psoas hitch. A flap of bladder is elevated, the ureter is reimplanted into this and the flap is closed as a tube (Figure 8.8). This allows good elevation of the bladder at the expense of reduced bladder capacity.

Bladder Damage

Avoiding damage

The bladder can also be damaged during closure of the vaginal vault, particularly if it has not been sufficiently mobilized. Sutures may be placed through the detrusor muscle or even into the bladder itself, although this rarely causes problems (Meeks et al 1997). However, if this is recognized at the time of surgery, such stitches should be removed and the bladder mobilized to allow closure of the vault without including the bladder. If damage to the bladder has occurred, this should be repaired and the bladder drained as discussed below.

Bowel Damage

Repair of bowel

Repair of damaged bowel may involve primary closure of a small hole or may be facilitated by the excision of a portion of unhealthy bowel and reanastomosis (Figure 8.9). Consideration should be given to a defunctioning colostomy proximal to anastomosis of large bowel, particularly if the blood supply to the bowel wall is compromised in any way. Factors that have a bearing on this decision are previous radiotherapy, bowel obstruction, gross infection of the operative field or other medical factors such as diabetes, steroid therapy, malignancy and advanced age. If no adverse factors are present, a colostomy may not be necessary. Small bowel usually heals without the need for defunctioning. If there is any doubt about the safety of a repair, a surgeon who specializes in bowel should be involved to help with the repair.

Laparoscopy

The incidence of complications in laparoscopic surgery relates very closely to the experience of the surgeon and the training they have received. Gynaecologists have built up extensive experience in the specialty with simple procedures over the last generation. Most senior house officers and junior registrars are trained in diagnostic laparoscopy as one of their earliest procedures. Nevertheless, adoption of the more advanced operative techniques has been slow, and experience in these areas is still very limited. If a high incidence of complications is to be avoided, it is essential that individual surgeons are well trained in the procedures they undertake. General complications of laparoscopy will be discussed but consideration of complications encountered in advanced laparoscopic surgery is outside the scope of this chapter (see Chapter 4, Laparoscopy, for more information).

Diathermy damage

KEY POINTS

Cruise PJE, Foord R. A 5 year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Archives of Surgery. 1973;107:206.

Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Benedetti-Panici PL, et al. A multicentre collaborative study on the use of cold scalpel and electrocautery for midline abdominal incision. Amerian Journal of Surgery. 2001;181:128-132.

Meeks GR, Sams JO4th, Field KW, Fulp KW, Margolis MT. Formation of vesicovaginal fistula: the role of suture placement into the bladder during closure of the vaginal cuff after transabdominal hysterectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;177:1298-1303.

Niggebrugge AHP, Trimbos JB, Hermans J, Steup W-H, Van De Velde CJH. Influence of abdominal-wound closure technique on complications after surgery: a randomised study. The Lancet. 1999;353:1563-1567.

Orr JWJr, Garter JF, Kilgore LC, et al. Closed suction pelvic drainage following radical pelvic surgery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;155:867.

Orr JWJr, Orr PJ, Bolen DD, Holimon JL. Radical hysterectomy: does the type of incision matter? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;173:399-405.

Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists. Peritoneal Closure. Guideline No. 15. RCOG, London, 1998.

Rucinski J, Margolis M, Panagopoulos G, Wise L. Closure of the abdominal midline fascia: meta-analysis delineates the optimal technique. American Surgeon. 2001;67:421-462.

Scribner DRJr, Kamelle SA, Gould N, et al. A retrospective analysis of radical hysterectomies done for cervical cancer: is there a role for the Pfannenstiel incision? Gynecological Oncology. 2001;81:481-484.

Tulandi T, Hum HS, Gelfand MM. Closure of laparotomy incisions with or without peritoneal suturing and second look laparoscopy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;158:536.