Principles and Concepts

A musculoskeletal assessment requires a proper and thorough systematic examination of the patient. A correct diagnosis depends on a knowledge of functional anatomy, an accurate patient history, diligent observation, and a thorough examination. The differential diagnosis process involves the use of clinical signs and symptoms, physical examination, a knowledge of pathology and mechanisms of injury, provocative and palpation (motion) tests, and laboratory and diagnostic imaging techniques. It is only through a complete and systematic assessment that an accurate diagnosis can be made. The purpose of the assessment should be to fully and clearly understand the patient’s problems, from the patient’s perspective as well as the clinician’s, and the physical basis for the symptoms that have caused the patient to complain. As James Cyriax stated, “Diagnosis is only a matter of applying one’s anatomy.”1

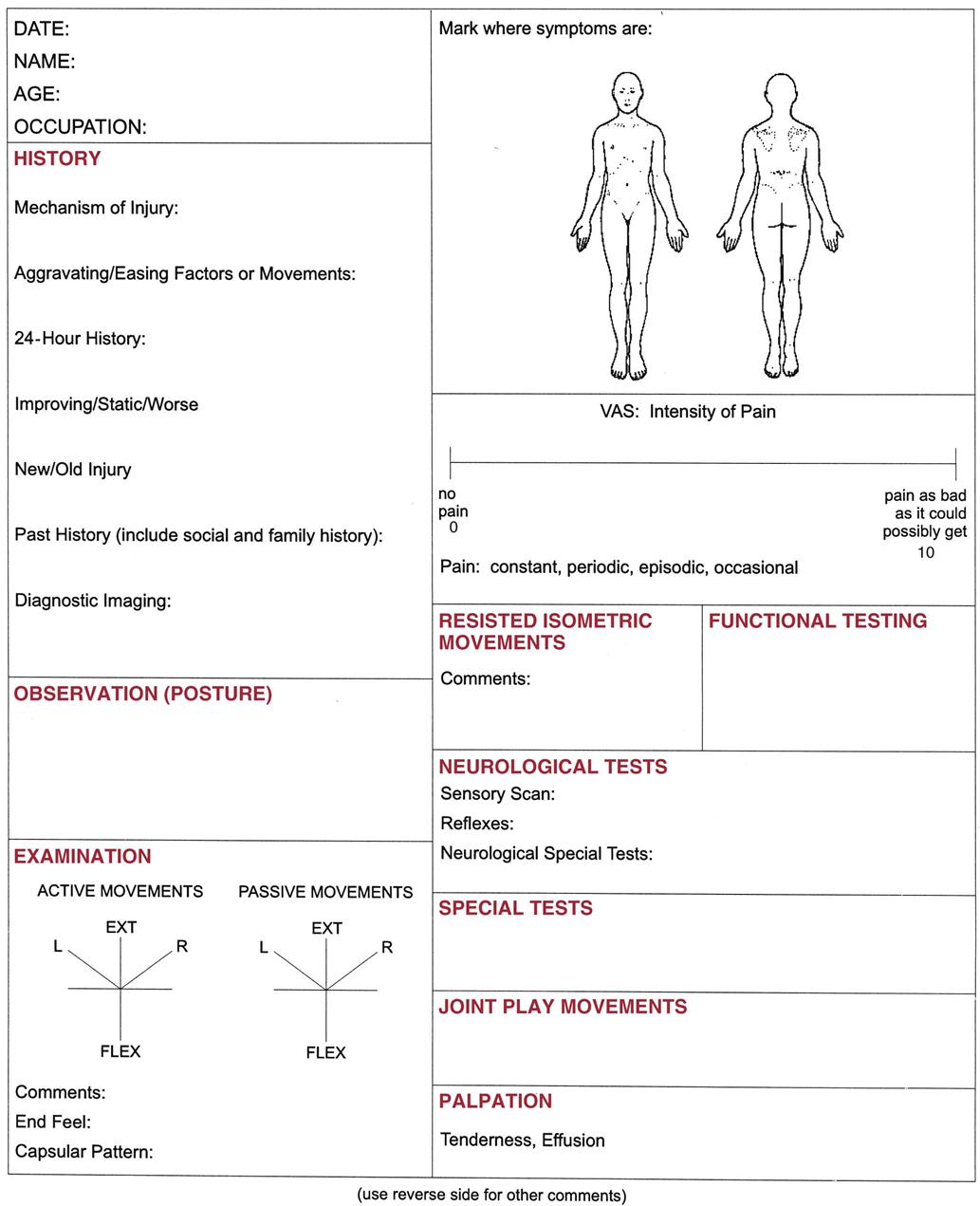

One of the more common assessment recording techniques is the problem-oriented medical records method, which uses “SOAP” notes.2 SOAP stands for the four parts of the assessment: Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan. This method is especially useful in helping the examiner to solve a problem. In this book, the subjective portion of the assessment is covered under the heading Patient History, objective under Observation, and assessment under Examination.

Although the text deals primarily with musculoskeletal physical assessment on an outpatient basis, it can easily be adapted to evaluate inpatients. The primary difference is in adapting the assessment to the needs of a bedridden patient. Often, an inpatient’s diagnosis has been made previously, and any continuing assessment is modified to determine how the patient’s condition is responding to treatment. Likewise, an outpatient is assessed continually during treatment, and the assessment is modified to reflect the patient’s response to treatment.

Regardless of which system is selected for assessment, the examiner should establish a sequential method to ensure that nothing is overlooked. The assessment must be organized, comprehensive, and reproducible. In general, the examiner compares one side of the body, which is assumed to be normal, with the other side of the body, which is abnormal or injured. For this reason, the examiner must come to understand and know the wide variability in what is considered normal. In addition, the examiner should focus attention on only one aspect of the assessment at a time, for example, ensuring a thorough history is taken before completing the examination component. When assessing an individual joint, the examiner must look at the joint and injury in the context of how the injury may affect other joints in the kinetic chain. These other joints may demonstrate changes as they try to compensate for the injured joint.

Each chapter ends with a summary, or précis, of the assessment procedures identified in that chapter. This section enables the examiner to quickly review the pertinent steps of assessment for the joint or structure being assessed. For further information, the examiner can refer to the more detailed sections of the chapter.

Patient History

A complete medical and injury history should be taken and written to ensure reliability. This requires effective and efficient communication on the part of the examiner and the ability to develop a good rapport with the patient and, in some cases, family members and other members of the health care team. This includes speaking at a level and using terms the patient will understand; taking the time to listen; and being empathic, interested, caring, and professional.3 Naturally, emphasis in taking the history should be placed on the portion of the assessment that has the greatest clinical relevance. Often the examiner can make the diagnosis by simply listening to the patient. No subject areas should be skipped. Repetition helps the examiner to become familiar with the characteristic history of the patient’s complaints so that unusual deviation, which often indicates problems, is noticed immediately. Even if the diagnosis is obvious, the history provides valuable information about the disorder, its present state, its prognosis, and the appropriate treatment. The history also enables the examiner to determine the type of person the patient is, his or her language and cognitive ability, the patient’s ability to articulate, any treatment the patient has received, and the behavior of the injury. In addition to the history of the present illness or injury, the examiner should note relevant past history, treatment, and results. Past medical history should include any major illnesses, surgery, accidents, or allergies. In some cases, it may be necessary to delve into the social and family histories of the patient if they appear relevant. Lifestyle habit patterns, including sleep patterns, stress, workload, and recreational pursuits, should also be noted.

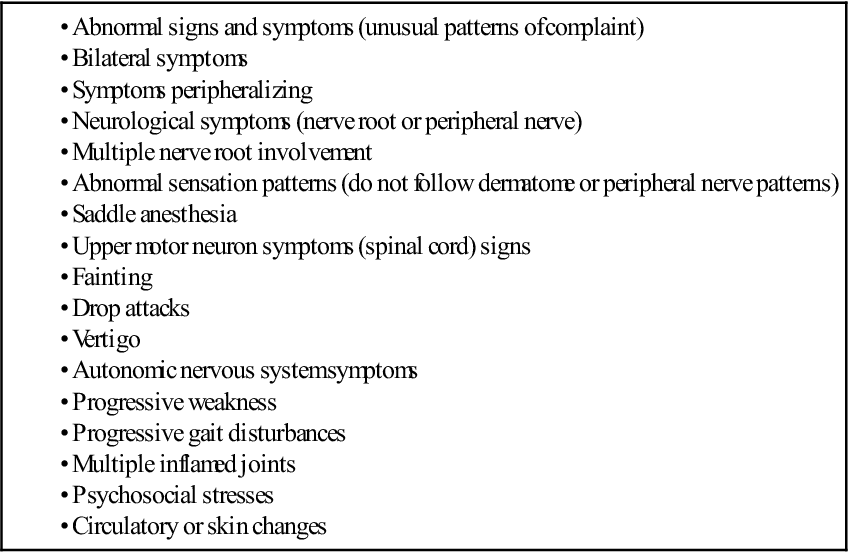

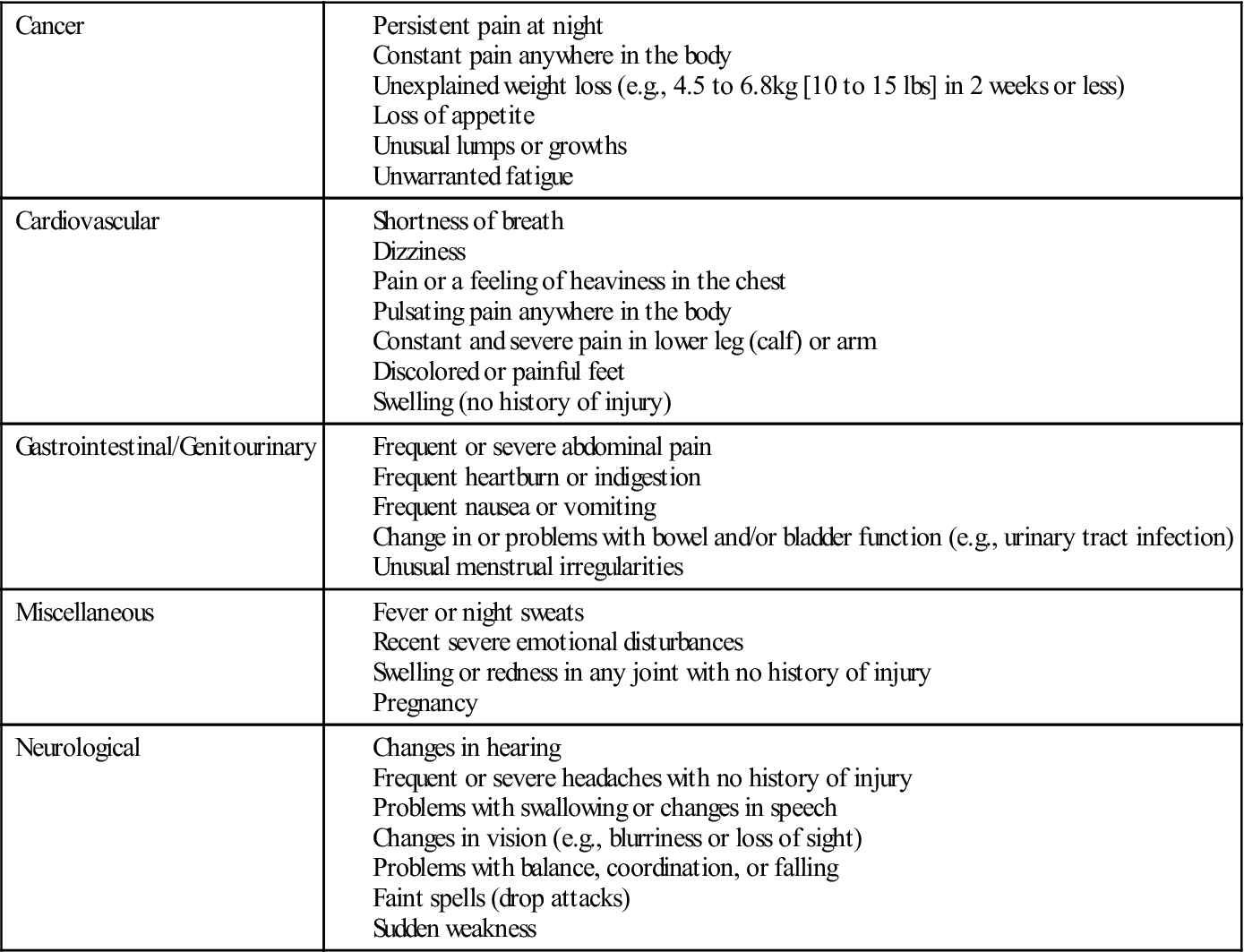

It is important that the examiner politely but firmly keeps the patient focused and discourages irrelevant information. Questions and answers should provide practical information about the problem. At the same time, to obtain optimum results in the assessment, it is important for the examiner to establish a good rapport with the patient. In addition, the examiner should listen for any potential red flag signs and symptoms (Table 1-1) that would indicate the problem is not a musculoskeletal one or a more serious problem that should be referred to the appropriate health care professional.4,5 Yellow flag signs and symptoms are also important for the examiner to note as they denote problems that may be more severe or may involve more than one area requiring a more extensive examination, or they may relate to cautions and contraindications to treatment that the examiner might have to consider, or they may indicate overlying psychosocial issues that may affect treatment.6

![]() TABLE 1-1

TABLE 1-1

Red Flag Findings in Patient History That Indicate Need for Referral to Physician

Data from Stith JS, Sahrmann SA, Dixon KK, et al: Curriculum to prepare diagnosticians in physical therapy. J Phys Ther Educ 9:50, 1995.

The patient’s history is usually taken in an orderly sequence. It offers the patient an opportunity to describe the problem and the limitations caused by the problem as he or she perceives them. To achieve a good functional outcome, it is essential that the clinician heed to the patient’s concerns and expectations for treatment. After all, the history is the patient’s report of his or her own condition. The clinician should ask questions that are easy to understand and should not lead the patient. For example, the examiner should not say, “Does this increase your pain?” It would be better to say, “Does this alter your pain in any way?” The examiner should ask one question at a time and receive an answer to each question before proceeding with another question. Open-ended questions ask for narrative information; closed or direct questions ask for specific information. Direct questions are often used to fill in details of information given in open-ended questions, and they frequently require only a one-word answer, such as yes or no. In any musculoskeletal assessment, the examiner should seek answers to the following pertinent questions.

2. What is the patient’s occupation? What does the patient do at work? What is the working environment like? What are the demands and postures assumed?7 For example, a laborer probably has stronger muscles than a sedentary worker and may be less likely to suffer a muscle strain. However, laborers are more susceptible to injury because of the types of jobs they have. Because sedentary workers usually have no need for high levels of muscle strength, they may overstress their muscles or joints on weekends because of overactivity or participation in activity that they are not used to. Habitual postures and repetitive strain caused by some occupations may indicate the location or source of the problem.

3. Why has the patient come for help? This is often referred to as the history of the present illness or chief complaint. This part of the history provides an opportunity for patients to describe in their own words what is bothering them and the extent to which it bothers them. It is important for the clinician to determine what the patient wants to be able to do functionally and what the patient is unable to do functionally. It is also essential to ensure that the clinician knows what is important to the patient in terms of outcome, whether the patient’s expectations for the following treatment are realistic, and what direction functional treatment should take to ensure the patient can, if at all possible, return to his or her previous level of activity or realize his or her expected outcome.8

4. Was there any inciting trauma (macrotrauma) or repetitive activity (microtrauma)? In other words, what was the mechanism of injury, and were there any predisposing factors? If the patient was in a motor vehicle accident, for example, was the patient the driver or the passenger? Was he or she the cause of the accident? What part of the car was hit? How fast were the cars going? Was the patient wearing a seat belt? When asking questions about the mechanism(s) of injury, the examiner must try to determine the direction and magnitude of the injuring force and how the force was applied. By carefully listening to the patient, the examiner can often determine which structures were injured and how severely by knowing the force and mechanism of injury. For example, anterior dislocations of the shoulder usually occur when the arm is abducted and laterally rotated beyond the normal range of motion (ROM), and the “terrible triad” injury to the knee (i.e., medial collateral ligament, anterior cruciate ligament, and medial meniscus injury) usually results from a blow to the lateral side of the knee while the knee is flexed, the full weight of the patient is on the knee, and the foot is fixed. Likewise, the examiner should determine whether there were any predisposing, unusual, or new factors (such as, sustained postures or repetitive activities, general health, or familial or genetic problems) that may have led to the problem.9

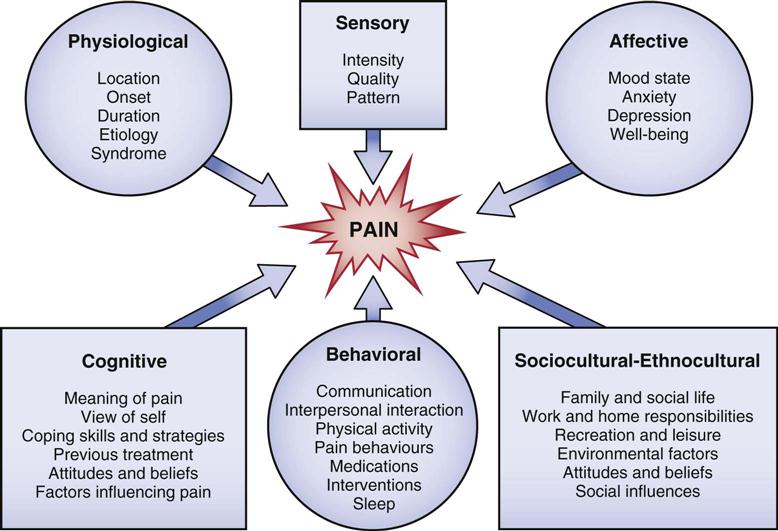

7. Where was the pain or other symptoms when the patient first had the complaint? Pain is subjective, and its manifestations are unique to each individual. It is a complex experience involving several dimensions (Figure 1-1).10 If the intensity of the pain or symptoms is such that the patient is unable to move in a certain direction or hold a particular posture because of the symptoms, the symptoms are said to be severe. If the symptoms or pain become progressively worse with movement or the longer a position is held, the symptoms are said to be irritable.11,12 Acute pain is new pain that is often severe, continuous, and perhaps disabling and is of sufficient quality or duration that the patient seeks help. Acute injuries tend to be more irritable resulting in pain earlier in the movement, or minimal activity will bring on symptoms, and often the pain will remain after movement has stopped.3 Chronic pain is more aggravating, is not as intense, has been experienced before, and in many cases, the patient knows how to deal with it. Acute pain is more often accompanied by anxiety, whereas chronic pain is associated with depression.13 When tissue has been damaged, substances are released leading to inflammation and peripheral sensitization of the nociceptors (also called primary hyperalgesia) resulting in localized pain. If the injury does not follow a normal healing pathway and becomes chronic, central sensitization (also called secondary hyperalgesia) may occur. Peripheral sensitization is a local phenomenon whereas central sensitization is a more central process involving the spinal cord and brain. Central sensitization manifests itself as widespread hypersensitivity to such physical, mental, and emotional stressors as touch, mechanical pressure, noise, bright light, temperature, and medication.14,15

Has the pain moved or spread? The location and spread of pain may be marked on a body chart, which is part of the assessment sheet (see Appendix 1-1). The examiner should ask the patient to point to exactly where the pain was and where it is now. Are trigger points present? Trigger points are localized areas of hyperirritability within the tissues; they are tender to compression, are often accompanied by tight bands of tissue, and, if sufficiently hypersensitive, may give rise to referred pain that is steady, deep, and aching. These trigger points can lead to a diagnosis, because pressure on them reproduces the patient’s symptoms. Trigger points are not found in normal muscles.16

In general, the area of pain enlarges or becomes more distal as the lesion worsens and becomes smaller or more localized as it improves. Some examiners call the former peripheralization of symptoms and the latter, centralization of symptoms.17–19 The more distal and superficial the problem, the more accurately the patient can determine the location of the pain. In the case of referred pain, the patient usually points out a general area; with a localized lesion, the patient points to a specific location. Referred pain tends to be felt deeply; its boundaries are indistinct, and it radiates segmentally without crossing the midline. The term, referred pain, means that the pain is felt at a site other than the injured tissue because the same or adjacent neural segments supply the referred site. Pain also may shift as the lesion shifts. For example, with an internal derangement of the knee, pain may occur in flexion one time and in extension another time if it is caused by a loose body within the joint. The examiner must clearly understand where the patient feels the pain. For example, does the pain occur only at the end of the ROM, in part of the range, or throughout the ROM?9

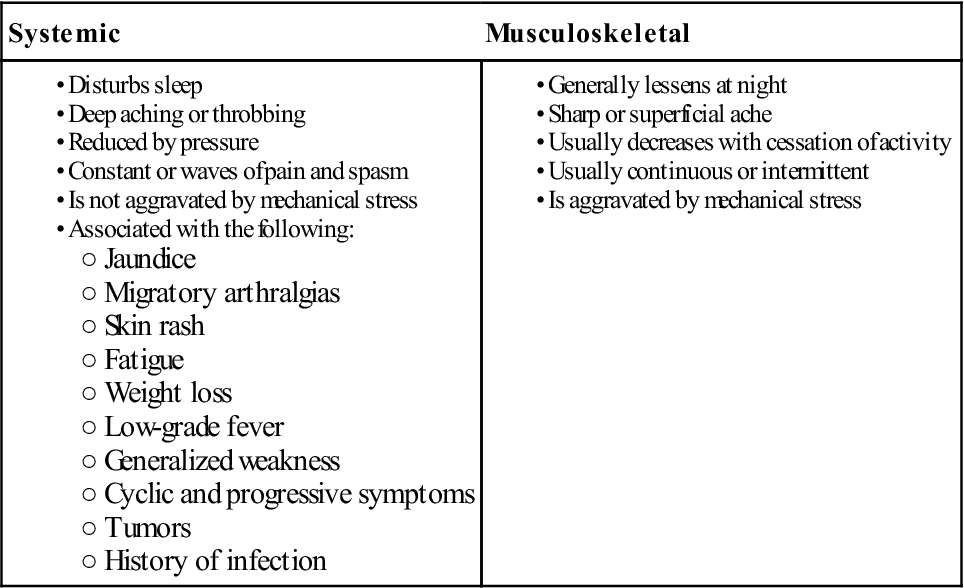

8. What are the exact movements or activities that cause pain? At this stage, the examiner should not ask the patient to do the movements or activities; this will take place during the examination. However, the examiner should remember which movements the patient says are painful so that when the examination is carried out, the patient can do these movements last to avoid an overflow of painful symptoms. With cessation of the activity, does the pain stay the same, or how long does it take for the pain to return to its previous level? Are there any other factors that aggravate or help to relieve the pain? Do these activities alter the intensity of the pain? The answers to these questions give the examiner some idea of the irritability of the joint. They also help the examiner to differentiate between musculoskeletal or mechanical pain and systemic pain, which is pain arising from one of the body’s systems other than the musculoskeletal system (Table 1-2).18 Functionally, pain can be divided into different levels, especially for repetitive stress conditions.

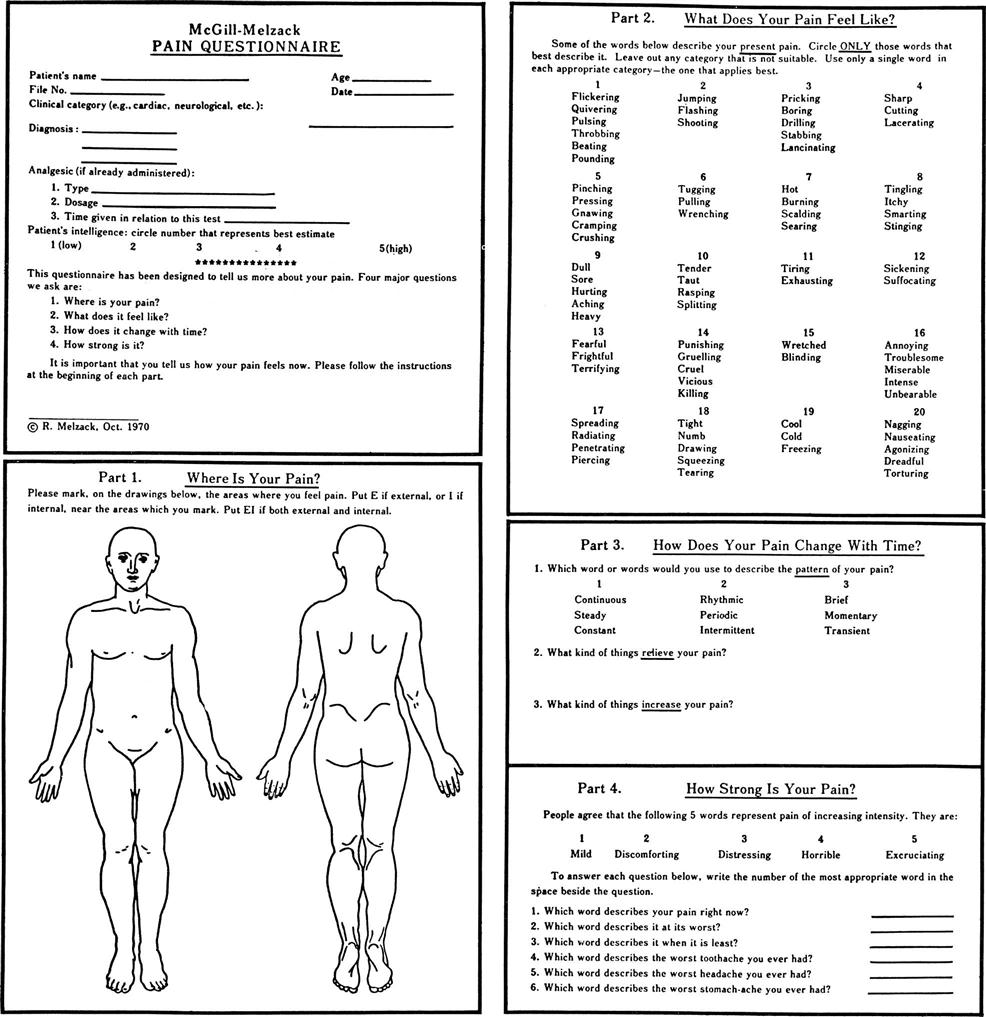

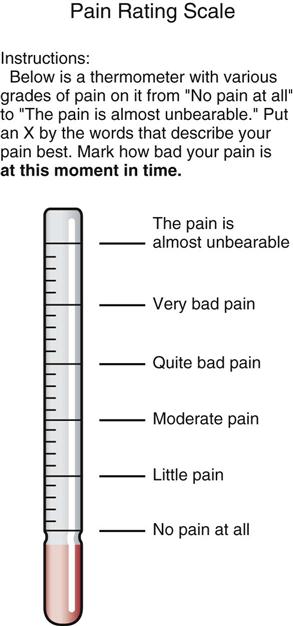

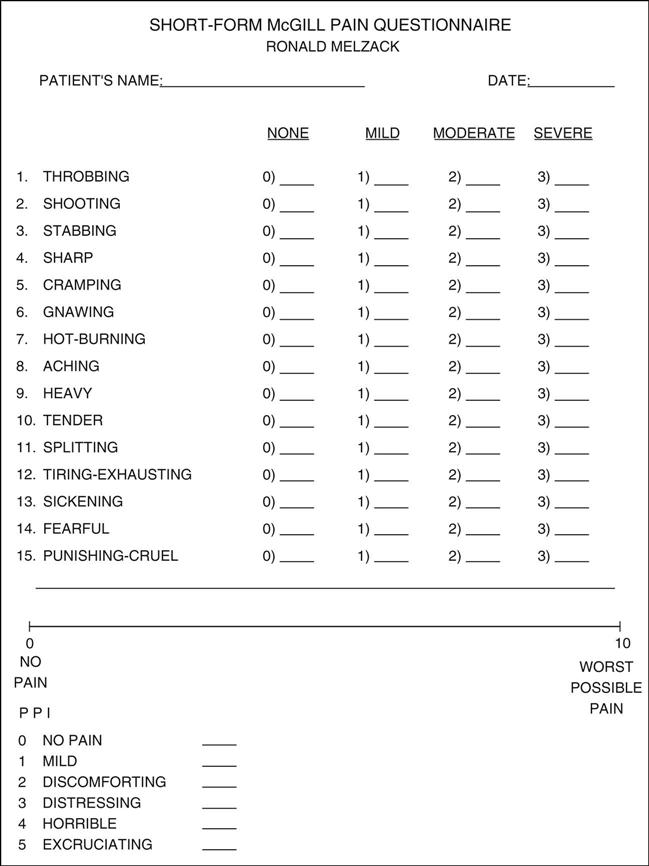

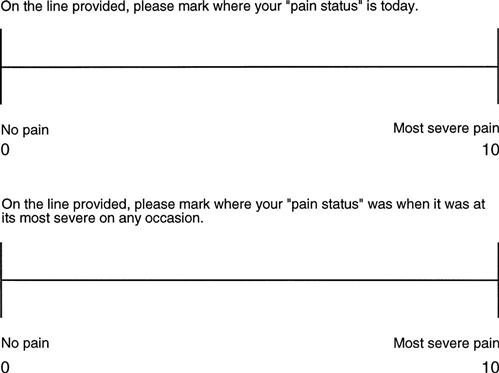

12. Are the intensity, duration, or frequency of pain or other symptoms increasing? These changes usually mean the condition is getting worse. A decrease in pain or other symptoms usually means the condition is improving. Is the pain static? If so, how long has it been that way? This question may help the examiner to determine the present state of the problem. These factors may become important in treatment and may help to determine whether a treatment is helping. Are pain or other symptoms associated with other physiological functions? For example, is the pain worse with menstruation? If so, when did the patient last have a pelvic examination? Questions such as these may give the examiner an indication of what is causing the problem or what factors may affect the problem. It is often worthwhile to give the patient a pain questionnaire, visual analog scale (VAS), numerical rating scale, box scale, or verbal rating scale that can be completed while the patient is waiting to be assessed.20,21 The McGill-Melzack pain questionnaire and its short form (Figures 1-2 and 1-3)22–24 provide the patient with three major classes of word descriptors—sensory, affective, and evaluative—to describe their pain experience. These designations are used to differentiate patients who have a true sensory pain experience from those who think they have experienced pain (affective pain state). Other pain-rating scales allow the patient to visually gauge the amount of pain along a solid 10-cm line (visual analogue scale) (Figure 1-4) or on a thermometer-type scale (Figure 1-5).25 It has been shown that an examiner should consistently use the same pain scales when assessing or reassessing patients to increase consistent results.26–29 The examiner can use the completed questionnaire or scale as an indication of the pain as described or perceived by the patient. Alternatively, a self-report pain drawing (see Appendix 1-1), which (with the training and guidelines of the raters) has been shown to have reliability, can be used for the same purpose.30

13. Is the pain constant, periodic, episodic (occurring with certain activities), or occasional? Does the condition bother the patient at that exact moment? If the patient is not bothered at that exact moment, the pain is not constant. Constant pain suggests chemical irritation, tumors, or possibly visceral lesions.18 It is always there, although its intensity may vary. If periodic or occasional pain is present, the examiner should try to determine the activity, position, or posture that irritates or brings on the symptoms, because this may help determine what tissues are at fault. This type of pain is more likely to be mechanical and related to movement and stress.18 Episodic pain is related to specific activities. At the same time, the examiner should be observing the patient. Does the patient appear to be in constant pain? Does the patient appear to be lacking sleep because of pain? Does the patient move around a great deal in an attempt to find a comfortable position?

14. Is the pain associated with rest? Activity? Certain postures? Visceral function? Time of day? Pain on activity that decreases with rest usually indicates a mechanical problem interfering with movement, such as adhesions. Morning pain with stiffness that improves with activity usually indicates chronic inflammation and edema, which decrease with motion. Pain or aching as the day progresses usually indicates increased congestion in a joint. Pain at rest and pain that is worse at the beginning of activity than at the end implies acute inflammation. Pain that is not affected by rest or activity usually indicates bone pain or could be related to organic or systemic disorders, such as cancer or diseases of the viscera. Chronic pain is often associated with multiple factors, such as fatigue or certain postures or activities. If the pain occurs at night, how does the patient lie in bed: supine, on the side, or prone? Does sleeping alter the pain, or does the patient wake when he or she changes position? Intractable pain at night may indicate serious pathology (e.g., a tumor). Movement seldom affects visceral pain unless the movement compresses or stretches the structure.11 Symptoms of peripheral nerve entrapment (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome) and thoracic outlet syndromes tend to be worse at night. Pain and cramping with prolonged walking may indicate lumbar spinal stenosis (neurogenic intermittent claudication) or vascular problems (circulatory or vascular intermittent claudication). Intervertebral disc pain is aggravated by sitting and bending forward. Facet joint pain is often relieved by sitting and bending forward and is aggravated by extension and rotation. What type of mattress and pillow does the patient use? Foam pillows often cause more problems for persons with cervical disorders because these pillows have more “bounce” to them than do feather or buckwheat pillows. Too many pillows, pillows improperly positioned, or too soft a mattress may also cause problems.

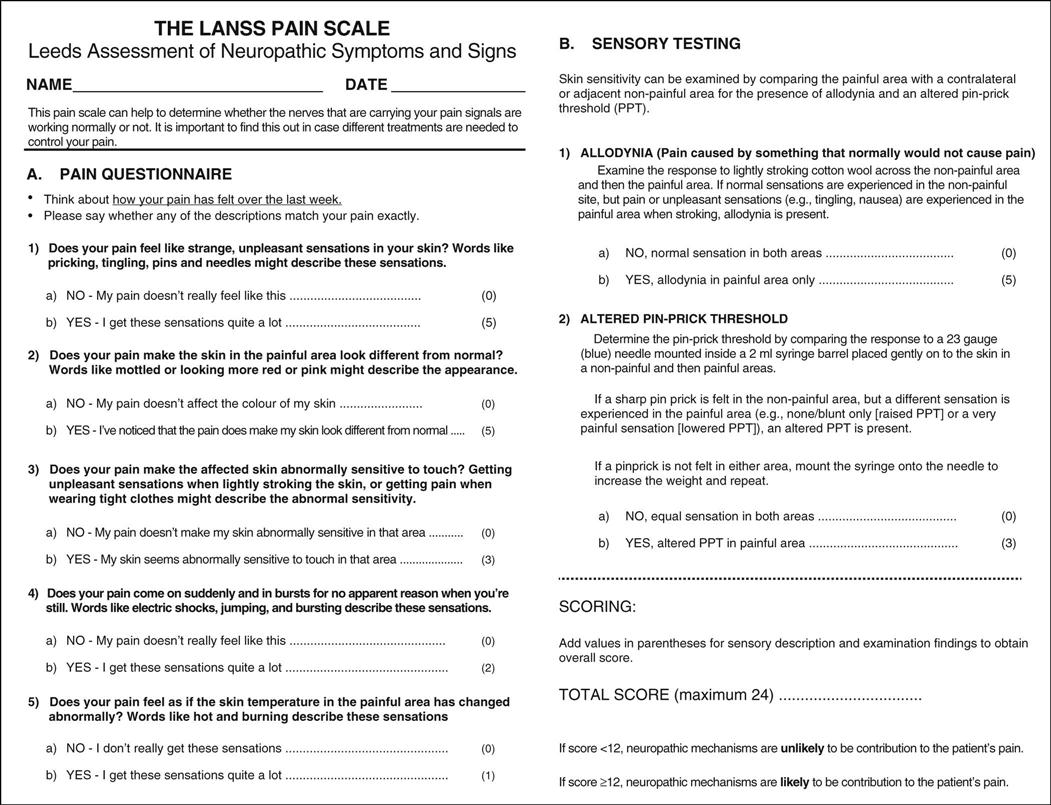

15. What type or quality of pain is exhibited? Nerve pain tends to be sharp (lancinating), bright, and burning and also tends to run in the distribution of specific nerves. Thus, the examiner must have detailed knowledge of the sensory distribution of nerve roots (dermatomes) and peripheral nerves as the different distributions may tell where the pathology or problem is if the nerve is involved. Bone pain tends to be deep, boring, and localized. Vascular pain tends to be diffuse, aching, and poorly localized and may be referred to other areas of the body. Muscle pain is usually hard to localize, is dull and aching, is often aggravated by injury, and may be referred to other areas (Table 1-3). If a muscle is injured, when the muscle contracts or is stretched, the pain will increase. Inert tissue, such as ligaments, joint capsules, and bursa, tend to exhibit pain similar to muscle pain and may be indistinguishable from muscle pain in the resting state (e.g., when the examiner is taking the history); however, pain in inert tissue is increased when the structures are stretched or pinched. Each of these specific tissue pains is sometimes grouped as neuropathic pain and follows specific anatomical pathways and affect specific anatomical structures.18 The Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) Pain Scale (Figure 1-6) has been developed to determine if neuropathic causes dominate the pain experience.31 Somatic pain, on the other hand, is a severe chronic or aching pain that is inconsistent with injury or pathology to specific anatomical structures and cannot be explained by any physical cause because the sensory input can come from so many different structures supplied by the same nerve root.12 Superficial somatic pain may be localized, but deep somatic pain is more diffuse and may be referred.32 On examination, somatic pain may be reproduced, but visceral pain is not reproduced by movement.32

17. Does a joint exhibit locking, unlocking, twinges, instability, or giving way? Seldom does locking mean that the joint will not move at all. Locking may mean that the joint cannot be fully extended, as is the case with a meniscal tear in the knee, or it may mean that it does not extend one time and does not flex the next time (pseudolocking), as in the case of a loose body moving within the joint. Locking may mean that the joint cannot be put through a full ROM because of muscle spasm or because the movement was too fast; this is sometimes referred to as spasm locking. Giving way is often caused by reflex inhibition or weakness of the muscles, and so the patient feels that the limb will buckle if weight is placed on it or the pain will be too great. Inhibition may be caused by anticipated pain or instability.

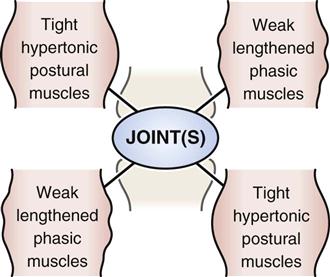

In nonpathological states, excessive ROM in a joint is called laxity or hypermobility. Laxity implies the patient has excessive ROM but can control movement in that range and no pathology is present. It is a function of the ligaments and joint capsule resistance.33 This differs from flexibility, which is the ROM available in one or more joints and is a function of contractile tissue resistance primarily as well as ligament and joint capsule resistance.33 Gleim and McHugh33 describe flexibility in two parts: static and dynamic. Static flexibility is related to the ROM available in one or more joints; dynamic flexibility is related to stiffness and ease of movement. Laxity may be caused by familial factors or may be job or activity (e.g., sports) related. In any case, laxity, when found, should be considered normal (Figure 1-7). If symptoms occur, then laxity is considered to be hypermobility and has a pathological component, which commonly indicates the patient’s inability to control the joint during movement, especially at end range, which implies instability of the joint. Instability can cover a wide range of pathological hypermobility from a loss of control of arthrokinematic joint movements to anatomical instability where subluxation or dislocation is imminent or has occurred. For assessment purposes, instability can be divided into translational (loss of arthrokinematic control) and anatomical (dislocation or subluxation) instability.34 Translational instability (also called pathological or mechanical instability) refers to loss of control of the small, arthrokinematic joint movements (e.g., spin, slide, roll, translation) that occur when the patient attempts to stabilize (statically or dynamically) the joint during movement. Anatomical instability (also called clinical or gross instability, or pathological hypermobility) refers to excessive or gross physiological movement in a joint where the patient becomes apprehensive at the end of the ROM because a subluxation or dislocation is imminent. It should be noted that there is confusion in the application of the terms used to describe the two types of instability. For example, mechanical instability is sometimes used to mean anatomical instability because of anatomical or pathological dysfunction. Functional instability may mean either or both types of instability and implies an inability to control either arthrokinematic or osteokinematic movement in the available ROM either consciously or unconsciously during functional movement. These instabilities are more likely to be evident during high-speed or loaded movements. Both types of instability can cause symptoms, and treatment centers on teaching the patient to develop muscular control of the joint and to improve reaction time and proprioceptive control. Both types of instability may be voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary instability is initiated by muscle contraction, and involuntary instability is the result of positioning. Another concept worth remembering during assessment for instability is the circle concept of instability, which was originally developed from shoulder studies35,36 but is equally applicable to other joints. This concept states that injury to structures on one side of a joint leading to instability can, at the same time, cause injury to structures on the other side or other parts of the joint. Thus, an anterior shoulder dislocation can lead to injury of the posterior capsule. Similarly, anterolateral rotary instability of the knee leads to injury to posterior structures (e.g., arcuate-popliteus complex, posterior capsule) as well as anterior (e.g., anterior cruciate ligament) and lateral (e.g., lateral collateral ligament) structures. Thus, the examiner must be aware of potential injuries on the opposite side of the joint even if symptoms are predominantly on one side, especially when the mechanism of injury is trauma.

18. Has the patient experienced any bilateral spinal cord symptoms, fainting, or drop attacks? Is bladder function normal? Is there any “saddle” involvement (abnormal sensation in the perianal region, buttocks, and superior aspect of the posterior thighs) or vertigo? “Vertigo” and “dizziness” are terms often used synonymously, although vertigo usually indicates more severe symptoms. The terms describe a swaying, spinning sensation accompanied by feelings of unsteadiness and loss of balance. These symptoms indicate severe neurological problems, such as cervical myelopathy, which must be dealt with carefully and can (e.g., in cases of altered bladder function) be emergency conditions potentially requiring surgery. Drop attacks occur when the patient suddenly falls without warning or provocation but remains conscious.18 It is caused by neurological dysfunction especially in the brain.

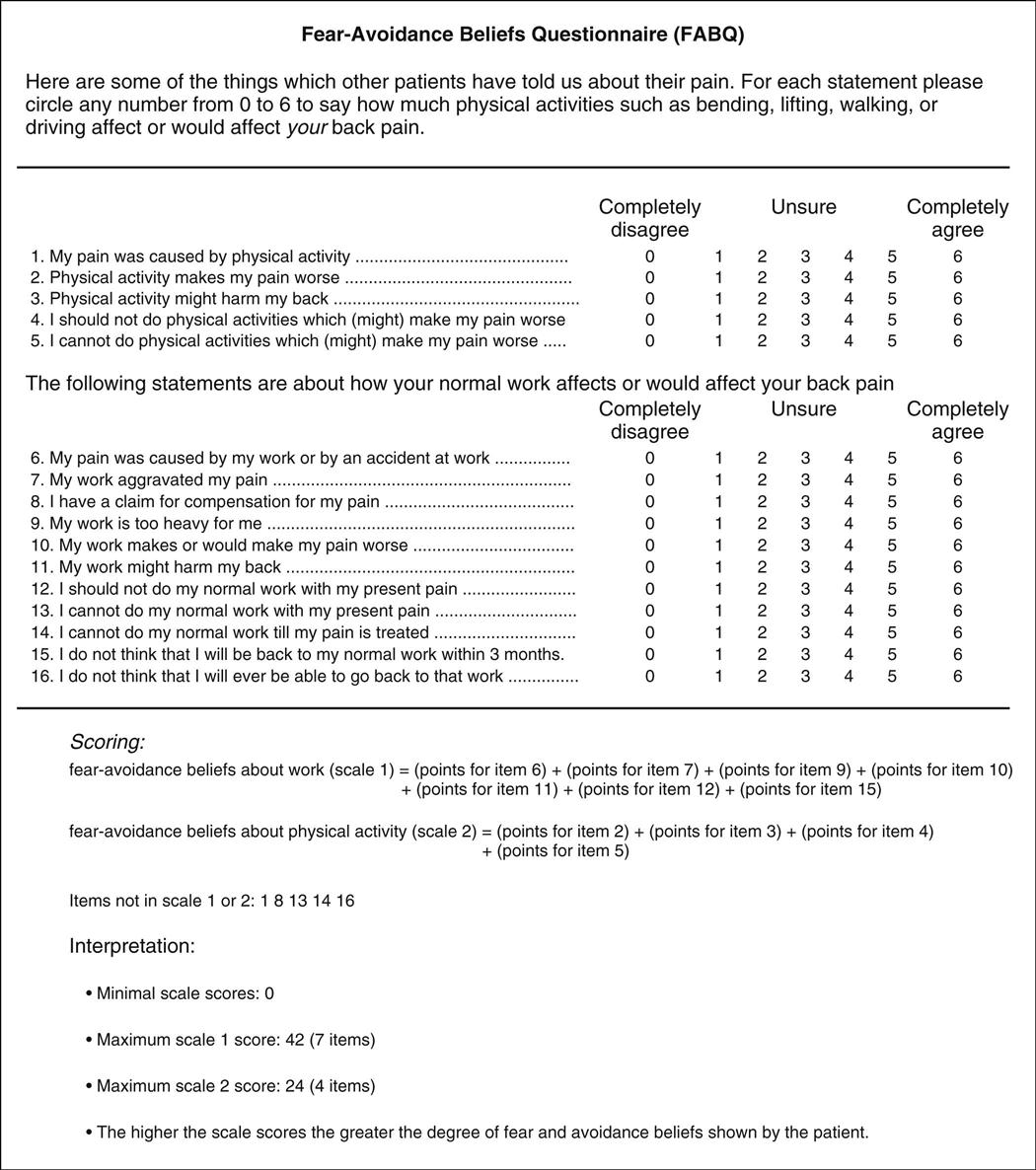

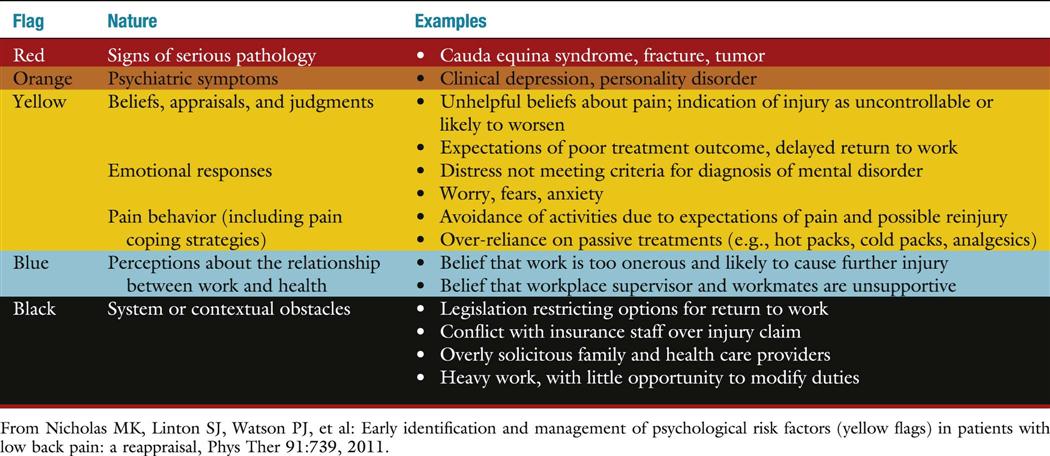

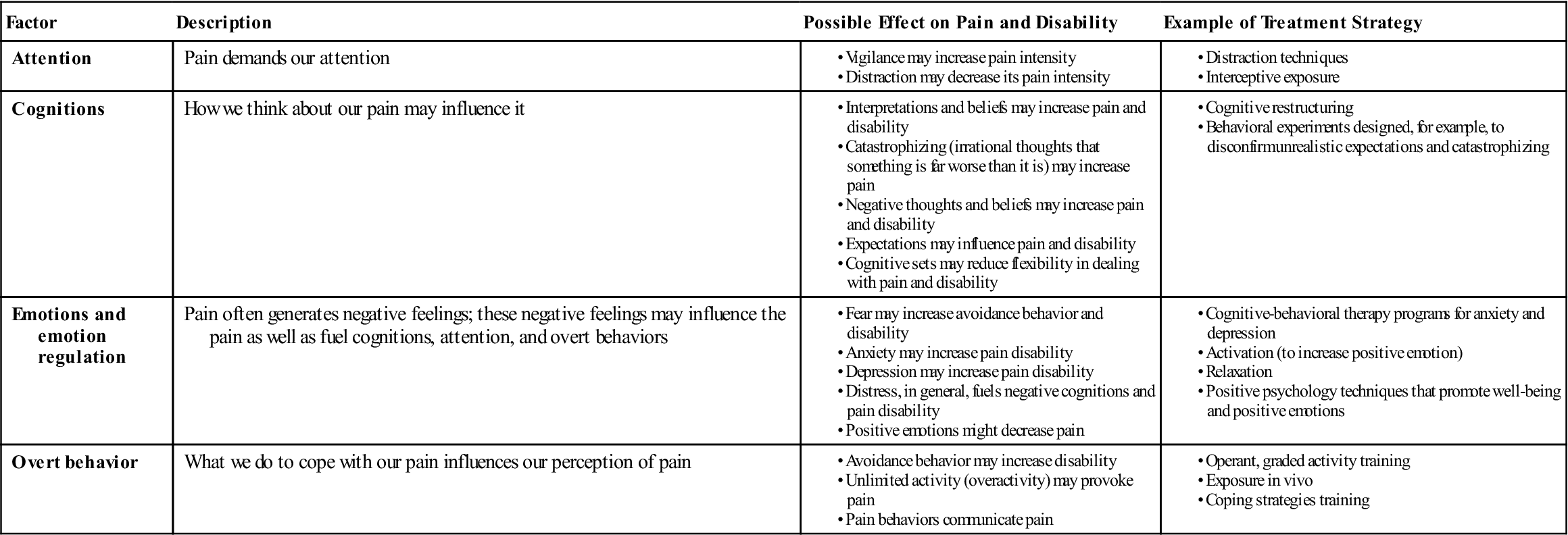

20. Has the patient been experiencing any life or economic stresses? These psychological stressors are sometimes considered to be yellow flags that alter both the assessment and subsequent treatment.37,38 Divorce, marital problems, financial problems, or job stress or insecurity can contribute to increasing the pain or symptoms because of psychological stress. What support systems and resources are available? Are there any cultural issues one should be aware of? Does the patient have an easily accessible living environment? Each of these issues may increase stress to the patient. Pain is often accentuated in patients with anxiety, depression, or hysteria, or patients may exaggerate their symptoms (symptom magnification) in the absence of objective signs, which may be called psychogenic pain.3,39,40 Thus, psychosocial aspects can play a significant role with injury.41–44 Because of the importance of these psychosocial aspects related to movement, questionnaires such as the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)45 (Figure 1-8) and the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia46–49 have been developed. Most of the studies related to the psychosocial aspects of injury have been related to the low back but could be used for other joints. The focus of these questionnaires is on the patient’s beliefs about how physical activity and work affect his or her injury and pain.42,50,51 Table 1-4 outlines some of the psychological processes affecting pain.42 These processes have been divided into different colored “flags” (Table 1-5), but it is important to note that these psychological flags, other than the red flag, are different from pathological “flags” previously mentioned.44 Waddell and Main37 consider illness behavior normal with patients who are exhibiting both a physical problem and varying degrees of illness behavior (Table 1-6). In these cases, it may be beneficial to determine the level of psychological stress or to refer the patient to another appropriate health care professional.38 When symptoms (such as, pain) appear to be exaggerated, the examiner must also consider the possibility that the patient is malingering. Malingering implies trying to obtain a particular gain by a conscious effort to deceive.52

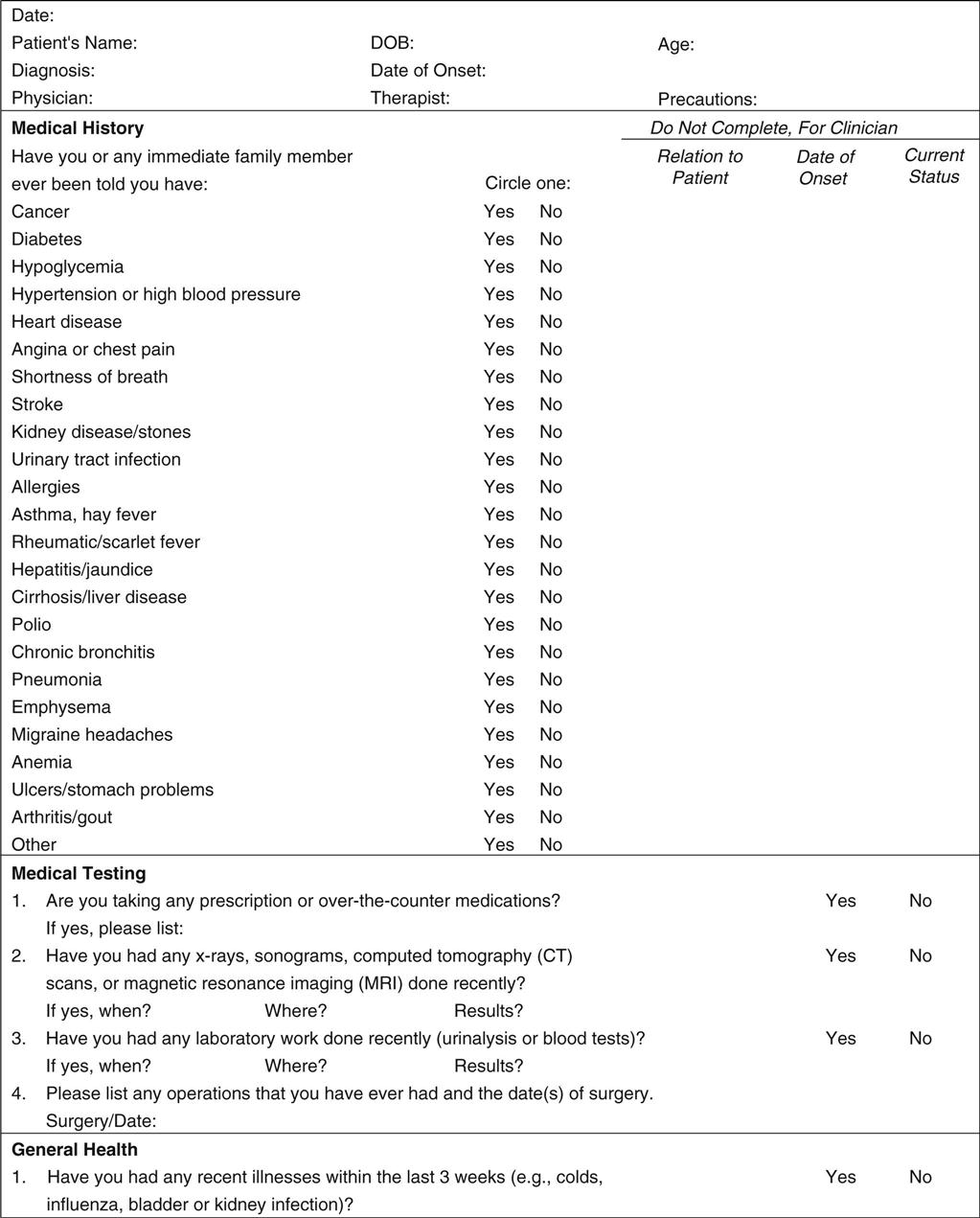

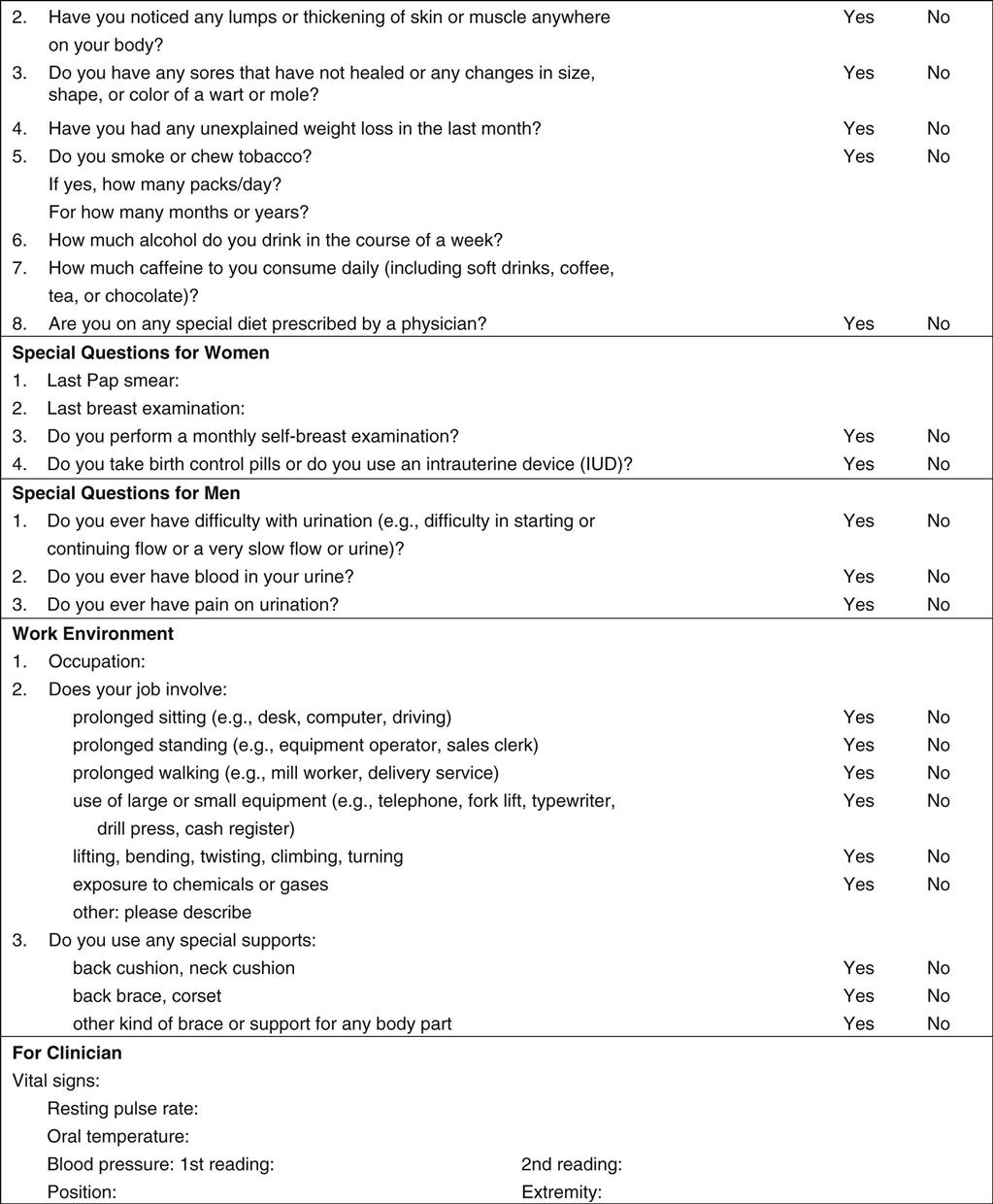

21. Does the patient have any chronic or serious systemic illnesses or adverse social habits (e.g., smoking, drinking) that may influence the course of the pathology or the treatment? In some cases, the examiner may use a medical history screening form (Figure 1-9) to determine the presence of conditions that may affect treatment or require referral to another health care professional.

24. Has the patient been receiving analgesic, steroid, or any other medication? If so, for how long? High dosages of steroids taken for long periods may lead to problems, such as osteoporosis. Has the patient been taking any other medication that is pertinent? Anticoagulants (such as, aspirin or anticoagulant therapy) increase the chance of bruising or hemarthrosis because the clotting mechanism is altered. Patients may not regard over-the-counter formulations, birth control pills, and so on as medications. If such medications have been taken for a long period, their use may not seem pertinent to the patient. How long has the patient been taking the medication? When did he or she last take the medication? Did the medication help?53 It is also important to determine whether medication is being taken for the condition under review. If analgesics or anti-inflammatories were taken just before the patient’s visit for the assessment, some symptoms may be masked.

25. Does the patient have a history of surgery or past/present illness? If so, when was the surgery performed, what was the site of operation, and what condition was being treated? Sometimes, the condition the examiner is asked to treat is the result of the surgery. Has the patient ever been hospitalized? If so, why? Health conditions such as high blood pressure, heart and circulatory problems, and systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes) should be noted because of their effect on healing, exercise prescription, and functional activities.3

TABLE 1-2

Differentiation of Systemic and Musculoskeletal Pain

From Meadows JT: Orthopedic differential diagnosis in physical therapy—a case study approach, New York, 1999, McGraw Hill, p. 100. Reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies.

Descriptors 1 to 11 represent the sensory dimension of pain experience, and descriptors 12 to 15 represent the affective dimension. Each descriptor is ranked on an intensity scale of 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe. The present pain intensity (PPI) of the standard long-form McGill pain questionnaire and the visual analogue scale (VAS) are also included to provide overall intensity scores. For actual examination, line would be 10 cm long. (Modified from Melzack R: The short-form McGill pain questionnaire. Pain 30:193, 1987.)

Example only. Note: For an actual examination, the lines would be 10 cm long.

TABLE 1-3

Pain Descriptions and Related Structures

| Type of Pain | Structure |

| Cramping, dull, aching | Muscle |

| Dull, aching | Ligament, joint capsule |

| Sharp, shooting | Nerve root |

| Sharp, bright, lightning-like | Nerve |

| Burning, pressure-like, stinging, aching | Sympathetic nerve |

| Deep, nagging, dull | Bone |

| Sharp, severe, intolerable | Fracture |

| Throbbing, diffuse | Vasculature |

This may also be called nonpathological hypermobility.

TABLE 1-4

Summary of Psychological Processes

Modified from Linton SJ, Shaw WS: Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys Ther 91:703, 2011.

TABLE 1-6

Spectrum of Clinical Symptoms and Signs

| Physical Disease | Illness Behavior | |

| Pain | ||

| Pain drawing | Localized Anatomic |

Nonanatomic Regional Magnified |

| Pain adjectives | Sensory | Emotional |

| Symptoms | ||

| Pain | Musculoskeletal or neurologic distribution | Whole leg pain Pain at the tip of the tailbone |

| Numbness | Dermatomal | Whole leg numbness |

| Weakness | Myotomal | Whole leg giving way |

| Time pattern | Varies with time and activity | Never free of pain |

| Response to treatment | Variable benefit | Intolerance of treatments Emergency hospitalization |

| Signs | ||

| Tenderness | Musculoskeletal distribution | Superficial Nonanatomic |

| Axial loading | Neck pain | Low back pain |

| Simulated rotation | Nerve root pain | Low back pain |

| Straight leg raising | Limited on formal examination No improvement on distraction |

Marked improvement with distraction |

| Motor | Myotomal | Regional, jerky, giving way |

| Sensory | Dermatomal | Regional |

From Waddell G, Main CJ: Illness behavior. In Waddell G, editor: The back pain revolution, Edinburgh, 1998, Churchill Livingstone, p. 162.

Taking an accurate, detailed history is very important. Listen to the patient—he or she is telling you what is wrong! With experience, the examiner should be able to make a preliminary “working” diagnosis from the history alone. The observation and examination phases of the assessment are then used to confirm, alter, or refute the possible diagnoses. What an examiner looks for in observation and tests for in examination is often related to what she or he has found when taking a history.

Observation

In an assessment, observation is the “looking” or inspection phase. Its purpose is to gain information on visible defects, functional deficits, and abnormalities of alignment. Much of the observation phase involves assessment of normal standing posture (see Chapter 15). Normal posture covers a wide range, and asymmetric findings are common. The key is to determine whether these findings are related to the pathology being presented. The examiner should note the patient’s way of moving as well as the general posture, manner, attitude, willingness to cooperate, and any signs of overt pain behavior.54 Observation may begin in the waiting room or as the patient is being taken to the assessment area. Often the patient is unaware that observation is occurring at this stage and may present a different picture. The patient must be adequately undressed in a private assessment area to be observed properly. Male patients should wear only shorts, and female patients should wear a bra or halter top and shorts. Because the patient is in a state of undress, it is essential for the examiner to explain that observation and detailed looking at the patient are integral parts of the assessment. This explanation may prevent a potentially embarrassing situation that can have legal ramifications.

As the patient enters the assessment area, the examiner should observe his or her gait (see Chapter 14). This initial gait assessment is only a cursory one; however, problems, such as Trendelenburg sign or drop foot, are easily noticed. If there appears to be an abnormality, the gait may be checked in greater detail after the patient has undressed.

The examiner should be positioned so that the dominant eye is used, and both sides of the patient should be compared simultaneously. During the observation stage, the examiner is only looking at the patient and does not ask the patient to move; the examiner usually does not palpate, except possibly to learn whether an area is warm or hot or to find specific landmarks.

After the patient has undressed, the examiner should observe the posture, looking for asymmetries and determining whether the asymmetries are significant or applicable to the problem being assessed. In doing so, the examiner should attempt to answer the following questions often by comparing both sides:

6. Because pelvic position plays such an important role in correct posture of the whole body, the examiner should determine if the patient can position the pelvis in the “neutral pelvis” position. This dynamic position is such that the anterior superior iliac spines are one-to-two finger widths lower than the posterior superior iliac spines on the same side in normal standing. When looking for the “neutral pelvis” position, the examiner must be able to answer three questions in the affirmative. If not, there are probably hypomobile and/or hypermobile structures affecting the pelvic position. The three questions are:

1) Can the patient get into the “neutral pelvis” position? (If not, why not?)

7. Are the color and texture of the skin normal? Does the appearance of the skin differ in the area of pain or symptoms, compared with other areas of the body? Ecchymosis or bruising indicates bleeding under the skin from injury to tissues (Figure 1-10). In some cases, this ecchymosis may track away from the injury site because of gravity. Trophic changes in the skin resulting from peripheral nerve lesions include loss of skin elasticity, shiny skin, hair loss on the skin, and skin that breaks down easily and heals slowly. The nails may become brittle and ridged. Skin disorders (such as, psoriasis) may affect joints (psoriatic arthritis). Cyanosis, or a bluish color to the skin, is usually an indication of poor blood perfusion. Redness indicates increased blood flow or inflammation.

On completion of the observation phase of the assessment, the examiner should return to the original preliminary working diagnosis made at the end of the history to see if any alteration in the diagnosis should be made with the additional information found in this phase.

Examination

Principles

Because the examination portion of the assessment involves touching the patient and may, in some cases, cause the patient discomfort, the examiner must obtain a valid consent to perform the examination before it begins. A valid consent must be voluntary, must cover the procedures to be done (informed consent), and the patient must be legally competent to give the consent (Appendix 1-2).55,56

The examination is used to confirm or refute the suspected diagnosis, which is based on the history and observation. The examination must be performed systematically with the examiner looking for a consistent pattern of signs and symptoms that leads to a differential diagnosis. Special care must be taken if the condition of the joint is irritable or acute. This is especially true if the area is in severe spasm or if the patient complains of severe unremitting pain that is not affected by position or medication, severe night pain, severe pain with no history of injury, or nonmechanical behavior of the joint.

In the examination portion of the assessment, a number of principles must be followed.

1. Unless bilateral movement is required, the normal side is tested first. Testing the normal side first allows the examiner to establish a baseline for normal movement for the joint being tested58 and shows the patient what to expect, resulting in increased patient confidence and less patient apprehension when the injured side is tested.

Vital Signs

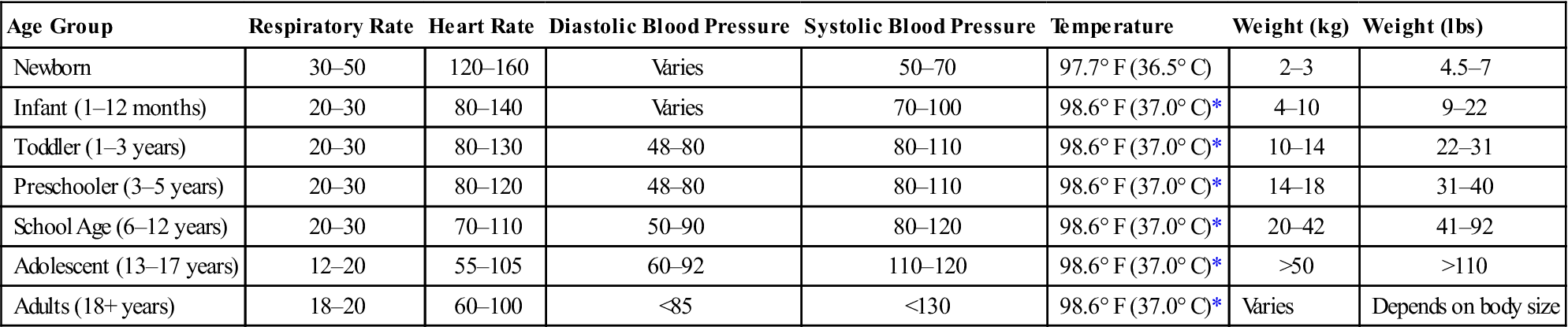

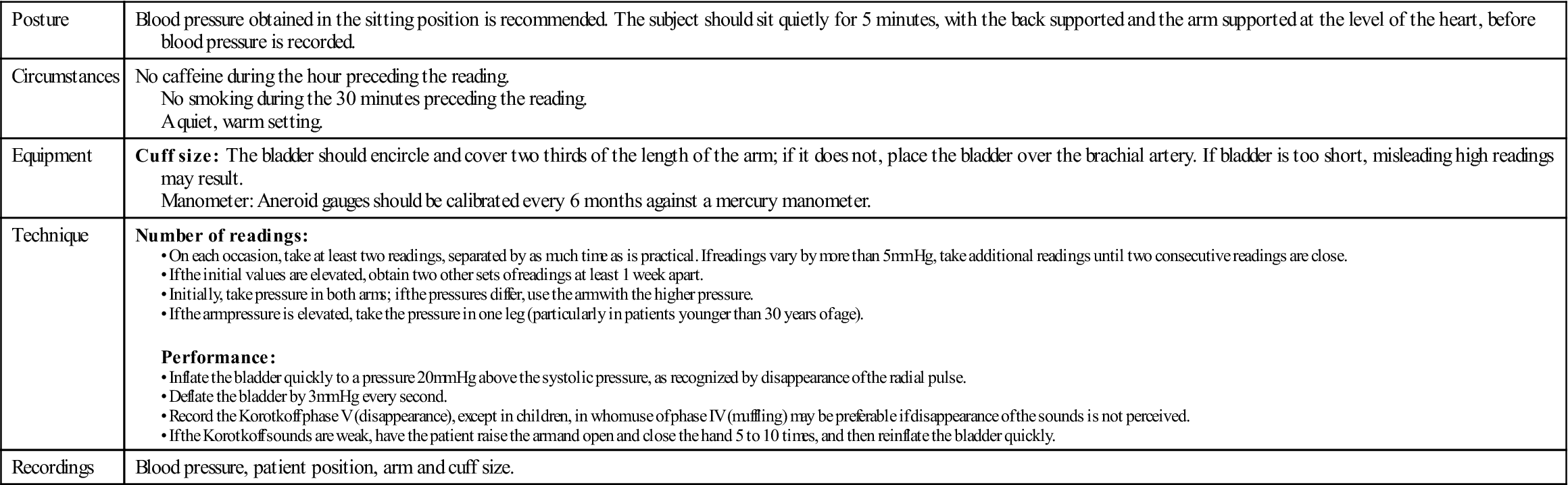

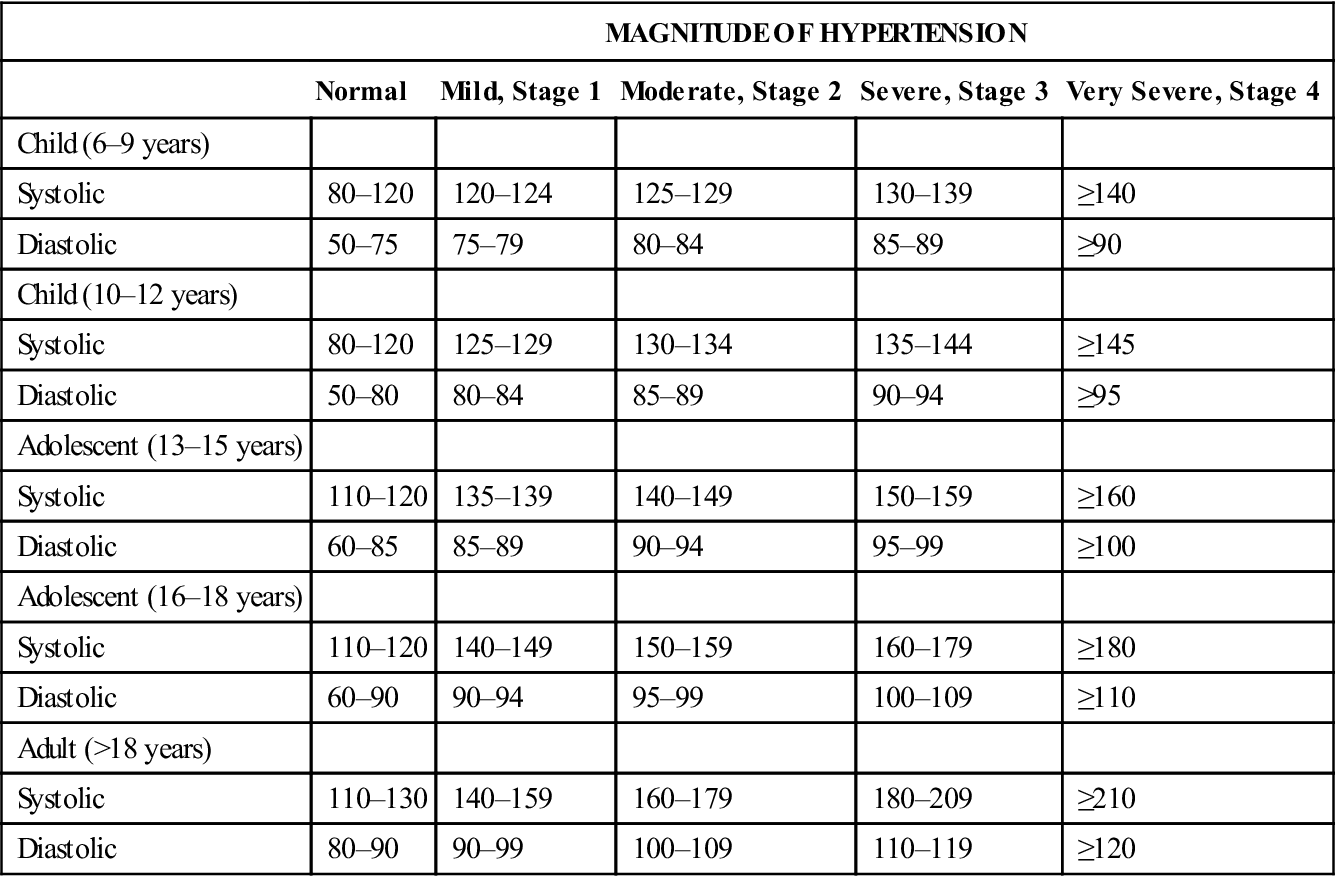

In some cases, the examiner may want to begin the examination by taking the patient’s vital signs to establish the patient’s baseline physiological parameters and vital signs (Table 1-7) and review the medical history screening card (see Figure 1-9). These include the pulse (most commonly the radial pulse at the wrist is used), blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature (98.4° F or 37° C is normal, but it may range from 96.5° F [35.8° C] to 99.4° F [37.4° C]), and weight. Table 1-8 outlines guidelines for blood pressure measurement. High blood pressure values should be checked several times at 15- to 30-minute intervals with the patient resting in between to determine whether a high reading is accurate or is being caused by anxiety (“white coat syndrome”) or some similar reason. If three consecutive readings are high, the patient is said to have high blood pressure (hypertension) (Table 1-9). If the readings remain high, further investigation may be warranted.59–61

TABLE 1-7

| Age Group | Respiratory Rate | Heart Rate | Diastolic Blood Pressure | Systolic Blood Pressure | Temperature | Weight (kg) | Weight (lbs) |

| Newborn | 30–50 | 120–160 | Varies | 50–70 | 97.7° F (36.5° C) | 2–3 | 4.5–7 |

| Infant (1–12 months) | 20–30 | 80–140 | Varies | 70–100 | 98.6° F (37.0° C)* | 4–10 | 9–22 |

| Toddler (1–3 years) | 20–30 | 80–130 | 48–80 | 80–110 | 98.6° F (37.0° C)* | 10–14 | 22–31 |

| Preschooler (3–5 years) | 20–30 | 80–120 | 48–80 | 80–110 | 98.6° F (37.0° C)* | 14–18 | 31–40 |

| School Age (6–12 years) | 20–30 | 70–110 | 50–90 | 80–120 | 98.6° F (37.0° C)* | 20–42 | 41–92 |

| Adolescent (13–17 years) | 12–20 | 55–105 | 60–92 | 110–120 | 98.6° F (37.0° C)* | >50 | >110 |

| Adults (18+ years) | 18–20 | 60–100 | <85 | <130 | 98.6° F (37.0° C)* | Varies | Depends on body size |

• The patient’s normal range should always be taken into consideration.

• Respiratory rate for infants should be counted for a full 60 seconds.

TABLE 1-8

Guidelines for Measurement of Blood Pressure

| Posture | Blood pressure obtained in the sitting position is recommended. The subject should sit quietly for 5 minutes, with the back supported and the arm supported at the level of the heart, before blood pressure is recorded. |

| Circumstances | No caffeine during the hour preceding the reading. No smoking during the 30 minutes preceding the reading. A quiet, warm setting. |

| Equipment | Cuff size: The bladder should encircle and cover two thirds of the length of the arm; if it does not, place the bladder over the brachial artery. If bladder is too short, misleading high readings may result. Manometer: Aneroid gauges should be calibrated every 6 months against a mercury manometer. |

| Technique | Number of readings: Performance: |

| Recordings | Blood pressure, patient position, arm and cuff size. |

From Kaplan NM, Deveraux RB, Miller HS: Systemic hyperextension. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26:S269, 1994.

TABLE 1-9

Classification of Hypertension by Age

| MAGNITUDE OF HYPERTENSION | |||||

| Normal | Mild, Stage 1 | Moderate, Stage 2 | Severe, Stage 3 | Very Severe, Stage 4 | |

| Child (6–9 years) | |||||

| Systolic | 80–120 | 120–124 | 125–129 | 130–139 | ≥140 |

| Diastolic | 50–75 | 75–79 | 80–84 | 85–89 | ≥90 |

| Child (10–12 years) | |||||

| Systolic | 80–120 | 125–129 | 130–134 | 135–144 | ≥145 |

| Diastolic | 50–80 | 80–84 | 85–89 | 90–94 | ≥95 |

| Adolescent (13–15 years) | |||||

| Systolic | 110–120 | 135–139 | 140–149 | 150–159 | ≥160 |

| Diastolic | 60–85 | 85–89 | 90–94 | 95–99 | ≥100 |

| Adolescent (16–18 years) | |||||

| Systolic | 110–120 | 140–149 | 150–159 | 160–179 | ≥180 |

| Diastolic | 60–90 | 90–94 | 95–99 | 100–109 | ≥110 |

| Adult (>18 years) | |||||

| Systolic | 110–130 | 140–159 | 160–179 | 180–209 | ≥210 |

| Diastolic | 80–90 | 90–99 | 100–109 | 110–119 | ≥120 |

Reprinted, by permission, from McGrew CA: Clinical implications of the AHA preparticipation cardiovascular screening guidelines. Athletic Ther Today 5(4):55, 2000.

Scanning Examination

The examination described in this book emphasizes the joints of the body, their movement and stability. It is necessary to examine all appropriate tissues to delineate the affected area, which can then be examined in detail. Application of tension, stretch, or isometric contraction to specific tissues produces either a normal or an appropriate abnormal response. This action enables the examiner to determine the nature and site of the present symptoms and the patient’s response to these symptoms. The examination shows whether certain activities provoke or change the patient’s pain; in this way, the examiner can focus on the subjective response (i.e., the patient’s feelings or opinions) as well as the test findings. The patient must be clear about his or her side of the examination. For instance, the patient must not confuse questions about movement-associated pain (“Does the movement make any difference to the pain?” “Does the movement bring on or change the pain?”) with questions about already existing pain. In addition, the examiner attempts to see whether patient responses are measurably abnormal. Do the movements cause any abnormalities in function? A loss of movement or weakness in muscles can be measured and therefore is an objective response. Throughout the assessment, the examiner looks for two sets of data: (1) what the patient feels (subjective) and (2) responses that can be measured or are found by the examiner (objective).

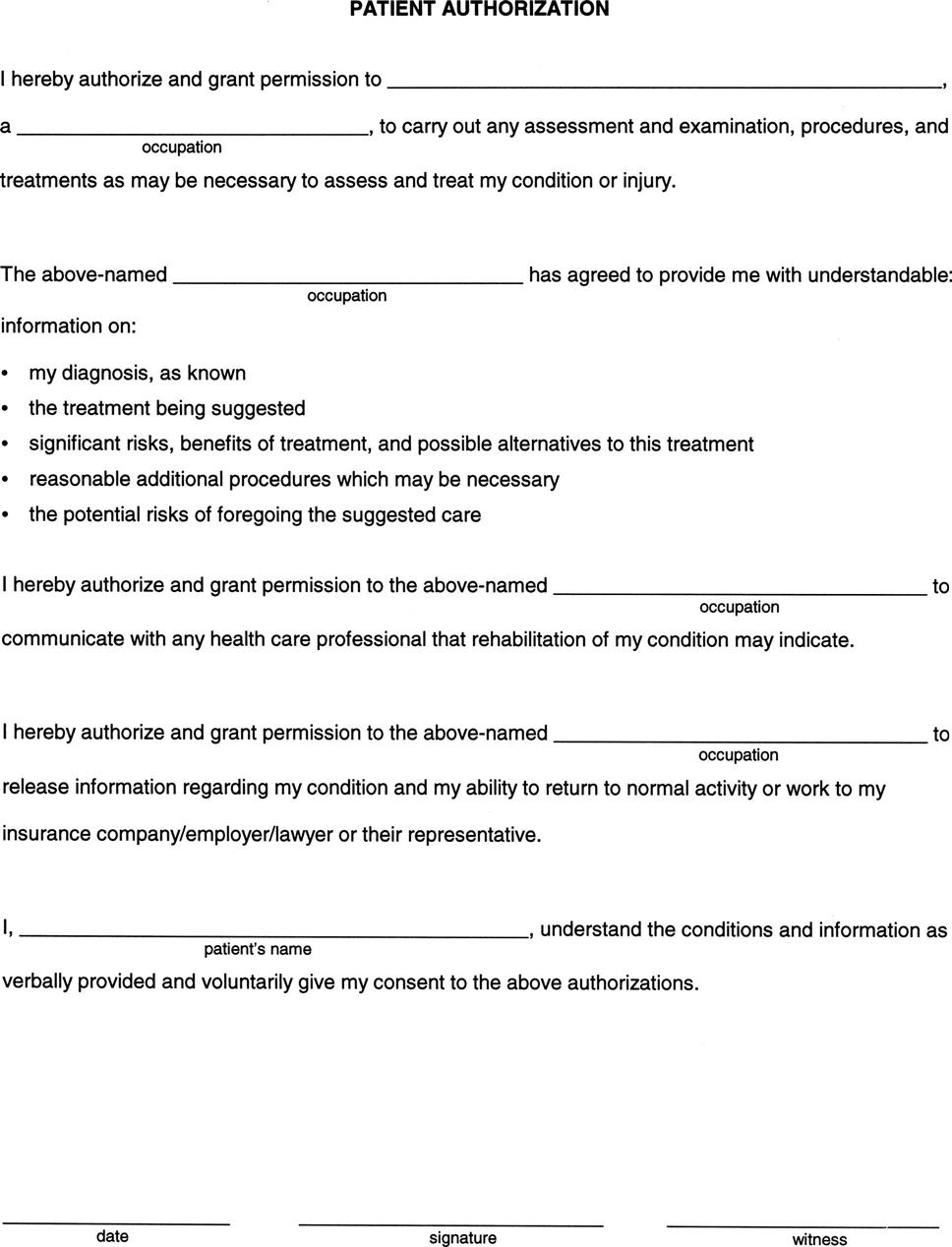

To ensure that all possible sources of pathology are assessed, the examination must be extensive. This is especially true if there are symptoms when no history of trauma is present. In this case, a scanning or screening examination is performed to rule out the possibility of referral of symptoms, especially from the spine. Similarly, if there is any doubt about where the pathology is located, the scanning examination is essential to ensure a correct diagnosis. The scanning examination is a “quick look” or scan of a part of the body involving the spine and extremities. It is used to rule out symptoms, which may be referred from one part of the body to another. It is divided into two scans: the upper limb scan and the lower limb scan. It is part of the examination that is used, where necessary, along with a detailed and focused examination of one or more of the joints.

As with all assessments, the use of a scanning examination depends on what the examiner found in the history and observation. For assessment of the spine, the scanning examination is integrated into the examination as a regular part of the cervical or lumbar assessment (Figure 1-11, A) and includes a peripheral joint scan, myotome testing, and a sensory scan. If, when assessing the peripheral joints, the examiner suspects a problem is being referred from the spine, the scanning examination is “inserted” into the examination of that joint (Figure 1-11, B). For the scanning examination, the peripheral joints are “scanned,” with the patient doing only a few key movements at each joint. The movements should include those that may be expected to exacerbate symptoms that are derived from the history. The examiner then tests the upper or lower limb myotomes (key muscles representing a specific nerve root). After these tests, a sensory scanning examination (sensory scan) can be performed that may include the appropriate reflexes, the sensory distributions of the dermatomes and peripheral nerve distribution, and selected neurodynamic tests (e.g., upper limb tension test, slump test) if the examiner suspects some neurological involvement. At this point, the examiner makes a decision or an “educated guess” as to whether the problem is in the cervical spine, lumbar spine, or the peripheral joint, based on the information gained. Once the decision is made, the examiner either completes the spinal assessment (in the case of a suspected spinal problem) or turns instead to completing the assessment of the appropriate peripheral joint (see Figure 1-11). The scanning examination should add no more than 5 or 10 minutes to the assessment.

The idea of the scanning examination was developed by James Cyriax,1 who also, more than any other author, originated the concepts of “contractile” and “inert” tissue, “end feel,” and “capsular patterns” and contributed greatly to development of a comprehensive and systematic physical examination of the moving parts of the body. Although several of his constructs and paradigms have been questioned,62–64 the basic principles of ensuring that all tissues are tested remains sound.

Spinal Cord and Nerve Roots

To further comprehend and ensure the value of the scanning examination, the examiner must have a clear understanding of signs and symptoms arising from the spinal cord and nerve roots of the body and those arising from peripheral nerves. The scanning examination helps to determine whether the pathology is caused by tissues innervated by a nerve root or peripheral nerve that is referring symptoms distally.

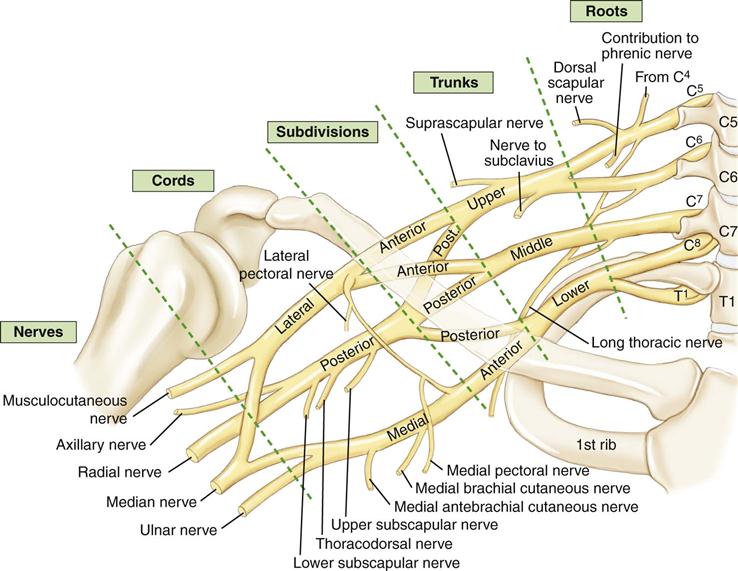

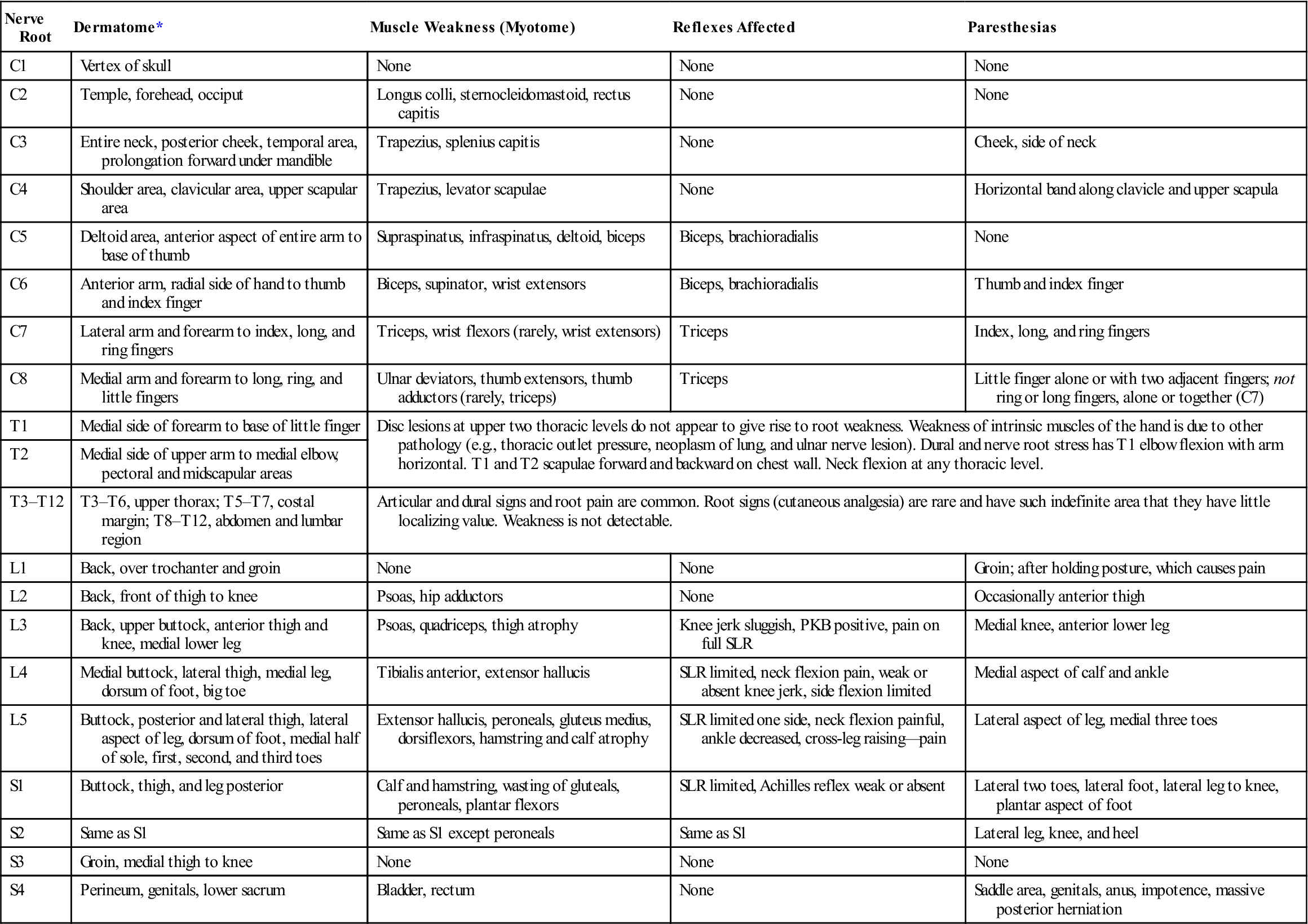

The nerve root is that portion of a peripheral nerve that “connects” the nerve to the spinal cord. Nerve roots arise from each level of the spinal cord (e.g., C3, C4), and many, but not all, intermingle in a plexus (brachial, lumbar, or lumbosacral) to form different peripheral nerves (Figure 1-12). This arrangement can result in a single nerve root supplying more than one peripheral nerve. For example, the median nerve is derived from the C6, C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots, whereas the ulnar nerve is derived from C7, C8, and T1 (Table 1-10). For this reason, if pressure is applied to the nerve root, the distribution of the sensation or motor function is often felt or exhibited in more than one peripheral nerve distribution (Table 1-11). Therefore, although the symptoms seen in a nerve root lesion (e.g., paresthesia, pain, muscle weakness) may be similar to those seen in peripheral nerves, the signs (e.g., area of paresthesia, where pain occurs, which muscles are weak) are commonly different. The examiner must be able to differentiate a dermatome (nerve root) from the sensory distribution of a peripheral nerve, and a myotome (nerve root) from muscles supplied by a specific peripheral nerve. In addition, neurological signs and symptoms, such as paresthesia and pain, may result from inflammation or irritation of tissues, such as facet joints and interspinous ligaments or other tissues supplied by the nerve roots, and they may be demonstrated in the dermatome, myotome, or sclerotome supplied by that nerve root. This irritation can contribute to the referred pain (see later discussion).

TABLE 1-10

Common Peripheral Nerves and Their Nerve Root Derivation

| Peripheral Nerve | Nerve Root Derivation |

| Axillary | C5,6 |

| Supraclavicular | C3,4 |

| Suprascapular | C5,6 |

| Subscapular | C5,6 |

| Long thoracic | C5,6,7 |

| Musculocutaneous | C5,6,7 |

| Medial cutaneous nerve of forearm | C8,T1 |

| Lateral cutaneous nerve of forearm | C5,6 |

| Posterior cutaneous nerve of forearm | C5,6,7,8 |

| Radial | C5,6,7,8,T1 |

| Median | C6,7,8,T1 |

| Ulnar | C(7)8,T1 |

| Pudendal | S2,3,4 |

| Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh | L2,3 |

| Medial cutaneous nerve of thigh | L2,3 |

| Intermediate cutaneous nerve of thigh | L2,3 |

| Posterior cutaneous nerve of thigh | S1,2,3 |

| Femoral | L2,3,4 |

| Obturator | L2,3,4 |

| Sciatic | L4,5,S1,2,3 |

| Tibial | L4,5,S1,2,3 |

| Common peroneal | L4,5,S1,2 |

| Superficial peroneal | L4,5,S1 |

| Deep peroneal | L4,5,S1,2 |

| Lateral cutaneous nerve of leg (calf) | L4,5,S1,2 |

| Saphenous | L3,4 |

| Sural | S1,2 |

| Medial plantar | L4,5 |

| Lateral plantar | S1,2 |

TABLE 1-11

Nerve Root Dermatomes, Myotomes, Reflexes, and Paresthetic Areas

| Nerve Root | Dermatome* | Muscle Weakness (Myotome) | Reflexes Affected | Paresthesias |

| C1 | Vertex of skull | None | None | None |

| C2 | Temple, forehead, occiput | Longus colli, sternocleidomastoid, rectus capitis | None | None |

| C3 | Entire neck, posterior cheek, temporal area, prolongation forward under mandible | Trapezius, splenius capitis | None | Cheek, side of neck |

| C4 | Shoulder area, clavicular area, upper scapular area | Trapezius, levator scapulae | None | Horizontal band along clavicle and upper scapula |

| C5 | Deltoid area, anterior aspect of entire arm to base of thumb | Supraspinatus, infraspinatus, deltoid, biceps | Biceps, brachioradialis | None |

| C6 | Anterior arm, radial side of hand to thumb and index finger | Biceps, supinator, wrist extensors | Biceps, brachioradialis | Thumb and index finger |

| C7 | Lateral arm and forearm to index, long, and ring fingers | Triceps, wrist flexors (rarely, wrist extensors) | Triceps | Index, long, and ring fingers |

| C8 | Medial arm and forearm to long, ring, and little fingers | Ulnar deviators, thumb extensors, thumb adductors (rarely, triceps) | Triceps | Little finger alone or with two adjacent fingers; not ring or long fingers, alone or together (C7) |

| T1 | Medial side of forearm to base of little finger | Disc lesions at upper two thoracic levels do not appear to give rise to root weakness. Weakness of intrinsic muscles of the hand is due to other pathology (e.g., thoracic outlet pressure, neoplasm of lung, and ulnar nerve lesion). Dural and nerve root stress has T1 elbow flexion with arm horizontal. T1 and T2 scapulae forward and backward on chest wall. Neck flexion at any thoracic level. | ||

| T2 | Medial side of upper arm to medial elbow, pectoral and midscapular areas | |||

| T3–T12 | T3–T6, upper thorax; T5–T7, costal margin; T8–T12, abdomen and lumbar region | Articular and dural signs and root pain are common. Root signs (cutaneous analgesia) are rare and have such indefinite area that they have little localizing value. Weakness is not detectable. | ||

| L1 | Back, over trochanter and groin | None | None | Groin; after holding posture, which causes pain |

| L2 | Back, front of thigh to knee | Psoas, hip adductors | None | Occasionally anterior thigh |

| L3 | Back, upper buttock, anterior thigh and knee, medial lower leg | Psoas, quadriceps, thigh atrophy | Knee jerk sluggish, PKB positive, pain on full SLR | Medial knee, anterior lower leg |

| L4 | Medial buttock, lateral thigh, medial leg, dorsum of foot, big toe | Tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis | SLR limited, neck flexion pain, weak or absent knee jerk, side flexion limited | Medial aspect of calf and ankle |

| L5 | Buttock, posterior and lateral thigh, lateral aspect of leg, dorsum of foot, medial half of sole, first, second, and third toes | Extensor hallucis, peroneals, gluteus medius, dorsiflexors, hamstring and calf atrophy | SLR limited one side, neck flexion painful, ankle decreased, cross-leg raising—pain | Lateral aspect of leg, medial three toes |

| S1 | Buttock, thigh, and leg posterior | Calf and hamstring, wasting of gluteals, peroneals, plantar flexors | SLR limited, Achilles reflex weak or absent | Lateral two toes, lateral foot, lateral leg to knee, plantar aspect of foot |

| S2 | Same as S1 | Same as S1 except peroneals | Same as S1 | Lateral leg, knee, and heel |

| S3 | Groin, medial thigh to knee | None | None | None |

| S4 | Perineum, genitals, lower sacrum | Bladder, rectum | None | Saddle area, genitals, anus, impotence, massive posterior herniation |

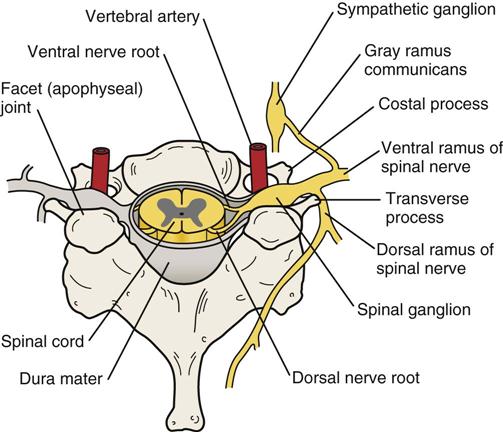

Nerve roots are made up of anterior (ventral) and posterior (dorsal) portions that unite near or in the intervertebral foramen to form a single nerve root or spinal nerve (Figure 1-13). They are the most proximal parts of the peripheral nervous system.

The human body has 31 nerve root pairs: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal. Each nerve root has two components: a somatic portion, which innervates the skeletal muscles and provides sensory input from the skin, fascia, muscles, and joints, and a visceral component, which is part of the autonomic nervous system.65 The autonomic system supplies the blood vessels, dura mater, periosteum, ligaments, and intervertebral discs, among many other structures.

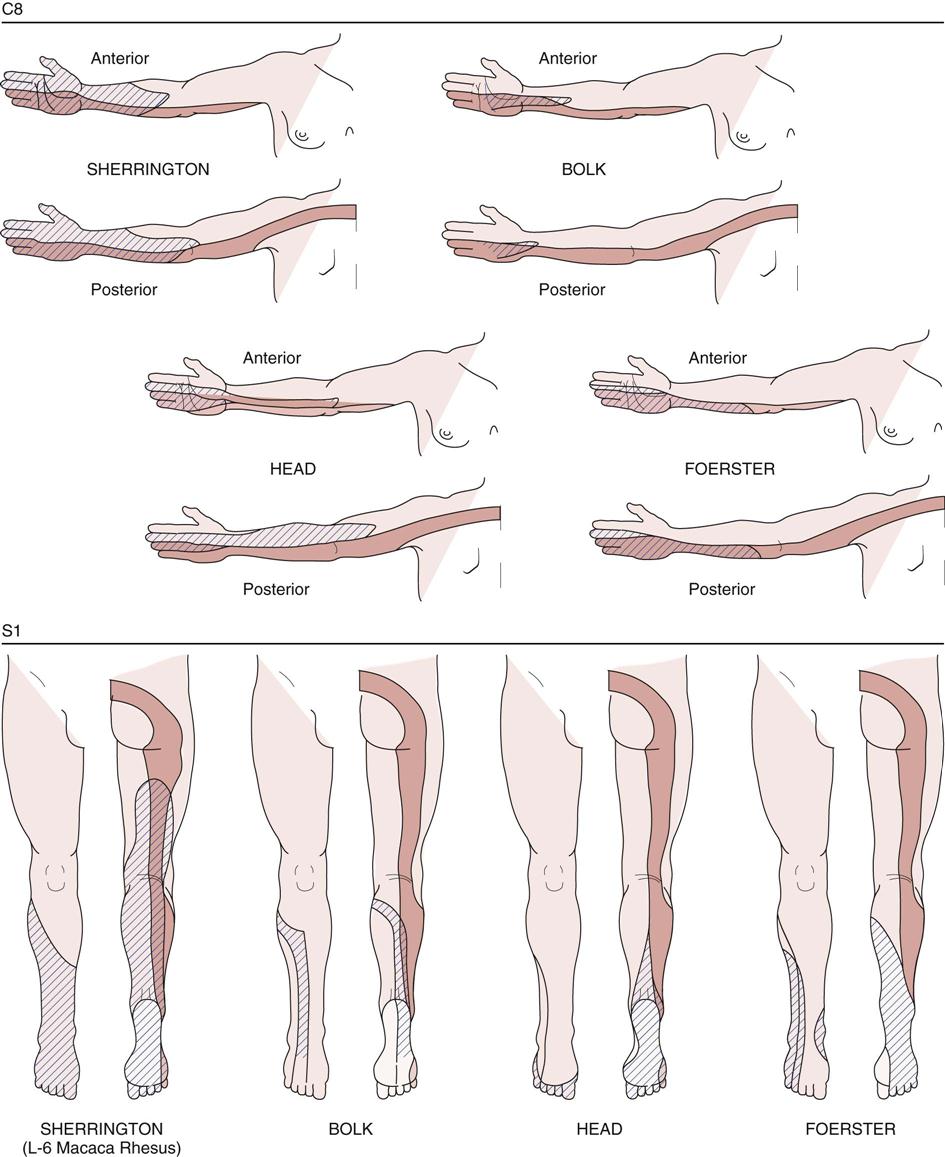

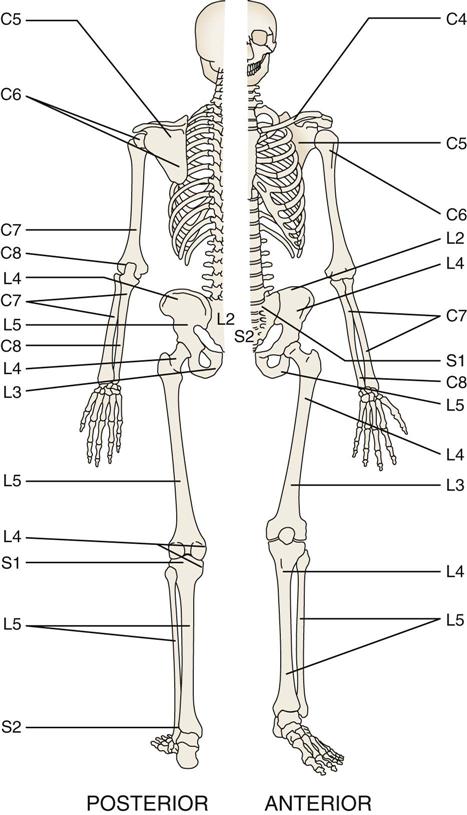

The sensory distribution of each nerve root is called the dermatome. A dermatome is defined as the area of skin supplied by a single nerve root. The area innervated by a nerve root is larger than that innervated by a peripheral nerve.66 The descriptions of dermatomes in the following chapters should be considered as examples only, because slight differences and variabilities occur with each patient, and dermatomes also exhibit a great deal of overlap.67,68 The variability in dermatomes was aptly demonstrated by Keegan and Garrett in 1948 (Figure 1-14).69 The overlap may be demonstrated by the fact that, in the thoracic spine, the loss of one dermatome often goes unnoticed because of the overlap of the adjacent dermatomes.

Spinal nerve roots have a poorly developed epineurium and lack a perineurium. This development makes the nerve root more susceptible to compressive forces, tensile deformation, chemical irritants (e.g., alcohol, lead, arsenic), and metabolic abnormalities. For example, compression of the nerve root could occur with a posterolateral intervertebral disc herniation, a “burner” or stretching of the nerve roots or the brachial plexus in a football player or alcoholic neuritis in an alcoholic. Pressure on nerve roots leads to loss of muscle tone and mass, but the loss is often not as obvious as when pressure is applied to a peripheral nerve. Because the peripheral nerve that innervates the muscle is usually supplied by more than one nerve root, more muscle fibers are likely to be affected and wasting or atrophy is more evident if the peripheral nerve itself is damaged. In addition, the pattern of weakness (i.e., which muscles are affected) is different for an injury to a nerve root and to a peripheral nerve, because a nerve root supplies more than one peripheral nerve. Pressure on a peripheral nerve resulting in a neuropraxia leads to temporary nonfunction of the nerve. With this type of injury, there is primarily motor involvement, with little sensory or autonomic involvement, and although weakness may be demonstrated, muscle atrophy may not be evident. With more severe peripheral nerve lesions (e.g., axonotmesis and neurotmesis), atrophy is evident.

Myotomes are defined as groups of muscles supplied by a single nerve root. A lesion of a single nerve root is usually associated with paresis (incomplete paralysis) of the myotome (muscles) supplied by that nerve root. It therefore takes time for any weakness to become evident on resisted isometric or myotome testing, and for this reason, the isometric testing of myotomes is held for at least 5 seconds. On the other hand, a lesion of a peripheral nerve leads to complete paralysis of the muscles supplied by that nerve, especially if the injury results in an axonotmesis or neurotmesis, and the weakness therefore is evident right away. Differences in the amount of resulting paralysis arise from the fact that more than one myotome contributes to the formation of a muscle embryologically.

A sclerotome is an area of bone or fascia supplied by a single nerve root (Figure 1-15). As with dermatomes, sclerotomes can show a great deal of variability among individuals.

Lines show areas of bone and fascia supplied by individual nerve roots.

It is the complex nature of the dermatomes, myotomes, and sclerotomes supplied by the nerve root that can lead to referred pain, which is pain felt in a part of the body that is usually a considerable distance from the tissues that have caused it. Referred pain is explained as an error in perception on the part of the brain. Usually, pain can be referred into the appropriate myotome, dermatome, or sclerotome from any somatic or visceral tissue innervated by a nerve root, but, confusingly, it sometimes is not referred according to a specific pattern.70 It is not understood why this occurs, but clinically it has been found to be so.

Many theories of the mechanism of referred pain have been developed, but none has been proven conclusively. Generally, referred pain may involve one or more of the following mechanisms:

1. Misinterpretation by the brain as to the source of the painful impulses

2. Inability of the brain to interpret a summation of noxious stimuli from various sources

3. Disturbance of the internuncial pool by afferent nerve impulses.

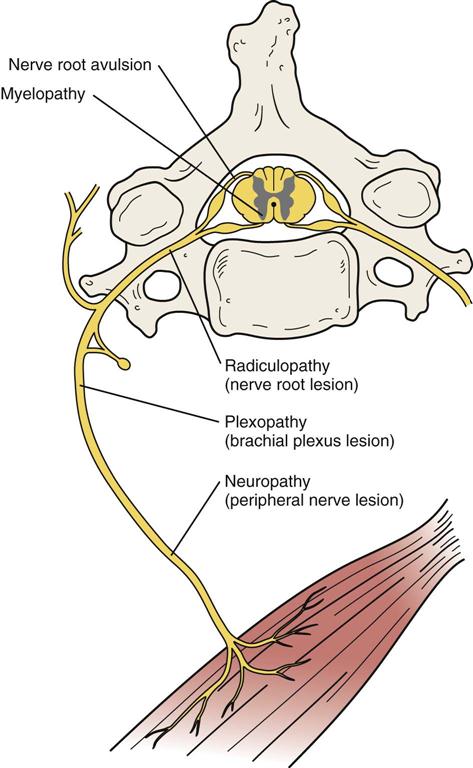

Referral of pain is a common occurrence in problems associated with the musculoskeletal system. Pain is often felt at points remote from the site of the lesion. The site to which pain is referred is an indicator of the segment that is at fault: it indicates that one of the structures innervated by a specific nerve root is causing signs and symptoms in other tissues supplied by that same nerve root. For example, pain in the L5 dermatome could arise from irritation around the L5 nerve root, from an L5 disc causing pressure on the L5 nerve root, from facet joint involvement at L4–L5 causing irritation of the L5 nerve root, from any muscle supplied by the L5 nerve root, or from any visceral structures having L5 innervation. Referred pain tends to be felt deeply; its boundaries are indistinct, and it radiates segmentally without crossing the midline. Radicular or radiating pain, a form of referred pain, is a sharp, shooting pain felt in a dermatome, myotome, or sclerotome because of direct involvement of or damage to a spinal nerve or nerve root.53 A radiculopathy refers to radiating paresthesia, numbness or weakness but not pain.71 A myelopathy is a neurogenic disorder involving the spinal cord or brain and resulting in an upper motor neuron lesion; the patterns of pain or symptoms are different from that of radicular pain, and often both upper and lower limbs are affected (Figure 1-16).

Peripheral Nerves

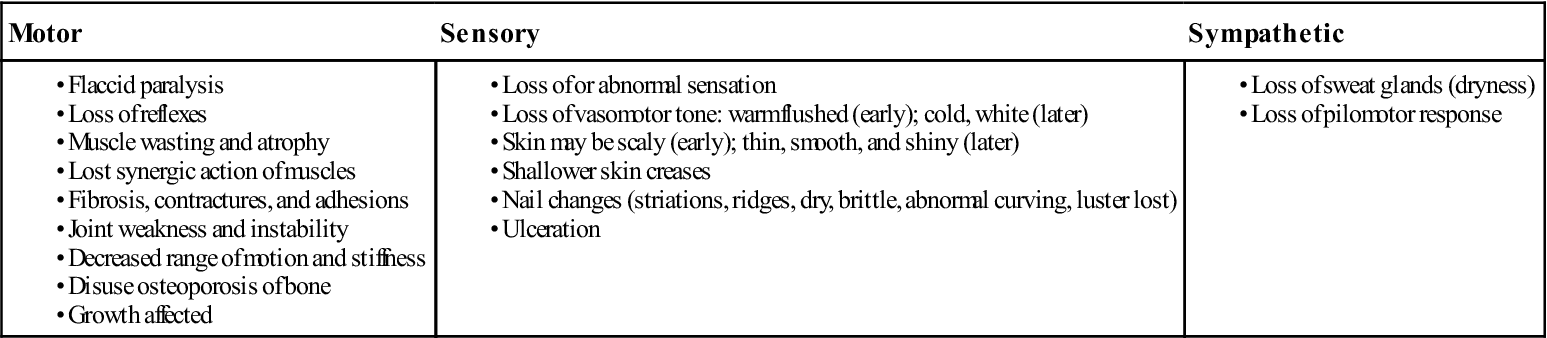

Peripheral nerves are a unique type of “inert” tissue (see the later discussion) in that they are not contractile tissue, but they are necessary for the normal functioning of voluntary muscle. The examiner must be aware of potential injury to nervous tissue when examining both contractile and inert tissue. Table 1-12 shows some of the tissue changes that result when a peripheral nerve lesion occurs.

TABLE 1-12

Signs and Symptoms of Mixed Peripheral Nerve (Lower Motor Neuron) Lesions*

In peripheral nerves, the epineurium consists of a loose areolar connective tissue matrix surrounding the nerve fiber. It allows changes in growth length of the bundled nerve fibers (funiculi) without allowing the bundles to be strained. The perineurium protects the nerve bundles by acting as a diffusion barrier to irritants and provides tensile strength and elasticity to the nerve. Peripheral nerves therefore are most commonly affected by pressure, traction, friction, anoxia, or cutting. Examples include pressure on the median nerve in the carpal tunnel, traction to the common peroneal nerve at the head of the fibula during a lateral ankle sprain, friction to the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel, anoxia of the anterior tibial nerve in a compartment syndrome, and cutting of the radial nerve with a fracture of the humeral shaft. Cooling, freezing, and thermal or electrical injury may also affect peripheral nerves.

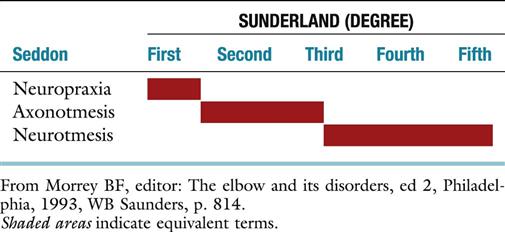

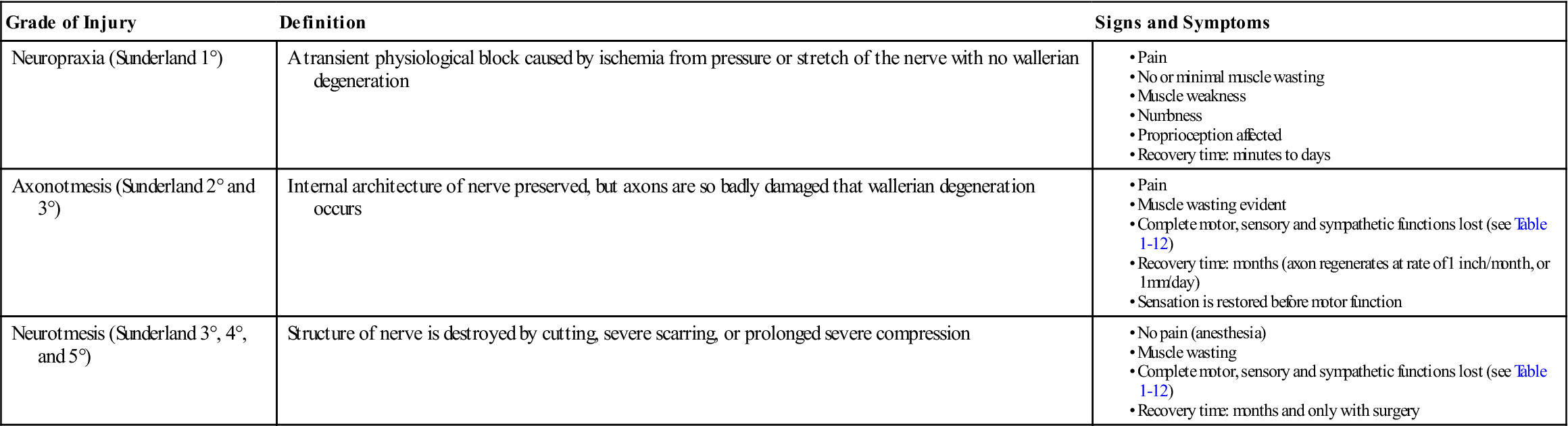

Nerve injuries are usually classified by the systems of Seddon72 or Sunderland.73 Seddon, whose system is most commonly used, classified nerve injuries into neuropraxia (most common), axonotmesis, and neurotmesis (Table 1-13). Sunderland followed a similar system but divided axonotmesis and neurotmesis into different levels or degrees (Table 1-14). Any examination of a joint must include a thorough peripheral nerve examination, especially if there are neurological signs and symptoms. The examiner must be able not only to differentiate inert tissue lesions from contractile tissue lesions but also to determine whether a contractile tissue malfunction is the result of the contractile tissue itself or a peripheral nerve lesion or a nerve root lesion.

TABLE 1-13

Classification of Nerve Injuries According to Seddon

Data from Seddon HJ: Three types of nerve injury. Brain 66:17–28, 1943.

Sensory loss combined with motor loss should alert the examiner to lesions of nervous tissue.74–76 Injury to a single peripheral nerve (e.g., the median nerve) is referred to as a mononeuropathy. Systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes) may affect more than one peripheral nerve. In this case, the pathology is referred to as a polyneuropathy. Careful mapping of the area of sensory loss and testing of the muscles affected by the motor loss allow the examiner to differentiate between a peripheral nerve lesion and a nerve root lesion. (An example is shown in Table 1-15.) If electromyographic studies are to be used to determine the grade of nerve injury, denervation cannot be evaluated for at least 3 weeks after injury to allow wallerian degeneration to occur and to allow regeneration (if any) to begin.77–79 Muscle wasting usually becomes obvious after 4 to 6 weeks and progresses to reach its maximum by about 12 weeks following injury. Circulatory changes after nerve injury vary with time. In the initial or early stages, the skin is warm, but after about 3 weeks, the skin becomes cooler as a result of decreased circulation. Because of the decreased circulation and altered cell metabolism, trophic changes occur to the skin and nails.

TABLE 1-15

Comparison of Signs and Symptoms for C7 Nerve Root Lesion and Median Nerve Lesion at Elbow

| C7 Nerve Root | Median Nerve | |

| Sensory alteration | Lateral arm and forearm to index, long, and ring fingers on palmar and dorsal aspect | Palmar aspect of thumb, index, middle, and half of ring finger Dorsal aspect of index, middle, and possibly half of ring finger |

| Motor alteration | Triceps Wrist flexors Wrist extensors (rarely) |

Pronator teres Wrist flexors (lateral half of flexor digitorum profundus) Palmaris longus Pronator quadratus Flexor pollicis longus and brevis Abductor pollicis brevis Opponens pollicis Lateral two lumbricals |

| Reflex alteration | Triceps may be affected | None* |

| Paresthesia | Index, long and ring fingers on palmar and dorsal aspect | Same as sensory alternation |

*No “common” reflexes are affected; if the examiner tested the tendon reflexes of the muscles listed, they would be affected.

When assessing a patient, the examiner must also be aware of what has been called the double-crush syndrome or double-entrapment neuropathy.80–83 The theory of this lesion (which has not yet been proved but has clinical supporting evidence) is that, whereas compression or pathology at one point along a peripheral nerve or nerve root may not be sufficient to cause signs and symptoms, compression or pathology at two or more points may lead to a cumulative effect that results in apparent signs and symptoms.84 Because of this cumulative effect, signs and symptoms may indicate one area of involvement (e.g., the carpal tunnel), whereas other areas (e.g., cervical spine, brachial plexus, thoracic outlet) may be contributing to the problem. Similarly, cervical lesions may be involved in tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) syndromes. Upton and McComas80 believed that compression proximally on the nerve trunk could increase the vulnerability of the peripheral nerves or nerve roots at distal points along their paths because axonal transport would be disrupted. In addition, diseased nerves are more susceptible to injury; thus, the presence of systemic disease (e.g., diabetes, thyroid dysfunction) may make the nerve more susceptible to compression somewhere along its path.75 Finally, the signs and symptoms could potentially be arising from both a nerve root lesion and a peripheral nerve lesion. Only with meticulous assessment can the clinician delineate where the true problems lie, which may be due to trauma, degeneration, or anatomical anomalies.

Similarly, the loss of extensibility of the nervous tissue at one site may produce increasing tensile loads when the peripheral nerve or nerve root is stretched, leading to mechanical dysfunction.85 This is the principle behind the neural tension or neurodynamic tests, such as the straight leg raise, slump test, and upper limb tension test,85–87 and may provide a partial explanation for lesions, such as cervical spine lesions mimicking tennis elbow and carpal tunnel syndrome. These tests put neural tissue (e.g., neuraxis of the central nervous system [CNS], meninges, nerve roots, peripheral nerves) under tension when they are performed and may duplicate symptoms that result during functional activity.85,87,88 For example, sitting in a car is closely mimicked by the action of the slump test and straight leg raising. However, they often do not, by themselves, indicate where the problem lies. Further testing (e.g., nerve conduction tests, electromyography [EMG]) may be needed to determine the exact site of the problem.

Neural tissue moves toward the joint at which elongation is initiated. Thus, if cervical flexion is initiated, the nerve roots, even those in the lumbar spine, move toward the cervical spine. Likewise, flexion of the whole spine causes movement toward the lumbar spine, and extension of the knee or dorsiflexion of the foot causes neural movement toward the knee or ankle.85,87,88 These “tension points” can potentially help determine where the restriction to movement is occurring. Normally, tension tests are not painful, although the patient is often aware of increased tension or discomfort in the spine or the limb. As tension tests indicate neural mobility and sensitivity to mechanical stresses, they are considered positive only if they reproduce the patient’s symptoms, or if the patient’s response is altered by movement of a body part distal to where the symptoms are felt (e.g., foot dorsiflexion causing symptoms in the lumbar spine), or if there is asymmetry in the response.85 When doing tension tests, the examiner should note the angle or position at which the restriction occurs and what the resistance feels like. With irritable conditions, only those parts of the test that are needed to cause positive results should be performed. For example, in the slump test, if neck flexion and slumping cause positive signs, there is no need to cause further discomfort to the patient by doing knee extension and foot dorsiflexion.

In the examination, testing of neurological tissue occurs during active, passive, and resisted isometric movement, as well as during functional testing, specific tests, reflexes, and cutaneous distribution and palpation.

Examination of Specific Joints

The examiner should use an unchanging, systematic approach to the examination that varies only slightly to elaborate certain clues given by the history or by asymmetric responses. For example, if the history is characteristic of a disc lesion, the examination should be a detailed one of all the tissues that may be affected by the disc and a brief one of all the other joints to exclude contradictory signs. If the history suggests arthritis of the hip, the examination should be a detailed one of the hip and a brief one of the other joints—again, to exclude contradictory signs. As the movements are tested, the examiner is looking sometimes for the patient’s subjective responses and sometimes for clinical objective findings. For example, if examination of the cervical spine shows clear signs of a disc problem, as the examination is continued down the arm, the examiner looks more for muscle weakness (objective) rather than for elicitation of pain (subjective). In contrast, if the history suggests a muscle lesion, pain will probably be provoked when the arm is examined. In either case, the structures expected to be normal are not omitted from the examination. There are only a few situations in which deviation from this systematic routine should occur: when there is uncertainty about where the pathology lies (in which case, a scanning examination must be performed with combined assessment of the spine and one or more peripheral joints); when there is no history of trauma or indication of pathology in a specific joint yet the patient complains of pain in that joint (again, a scanning examination is performed); or when the joint to be assessed is too acutely injured or irritable to do the total systematic examination.

If there is an organic lesion, some active, passive, or resisted isometric movements will be abnormal or painful, and others will not. Negative findings must balance positive ones, and the examination must be extensive enough to allow characteristic patterns to emerge. Determination of the problem is not made on the strength of the first positive finding; it is made only after it is clear that there are no other contradictory signs. Movements may be repeated several times quickly to rule out any problem, such as vascular insufficiency, or if the patient has indicated in the history that repetitive movements increase the symptoms. Likewise, sustained postures may be held for several seconds or combined movements may be performed if the history indicates increased symptoms with those postures or movements.

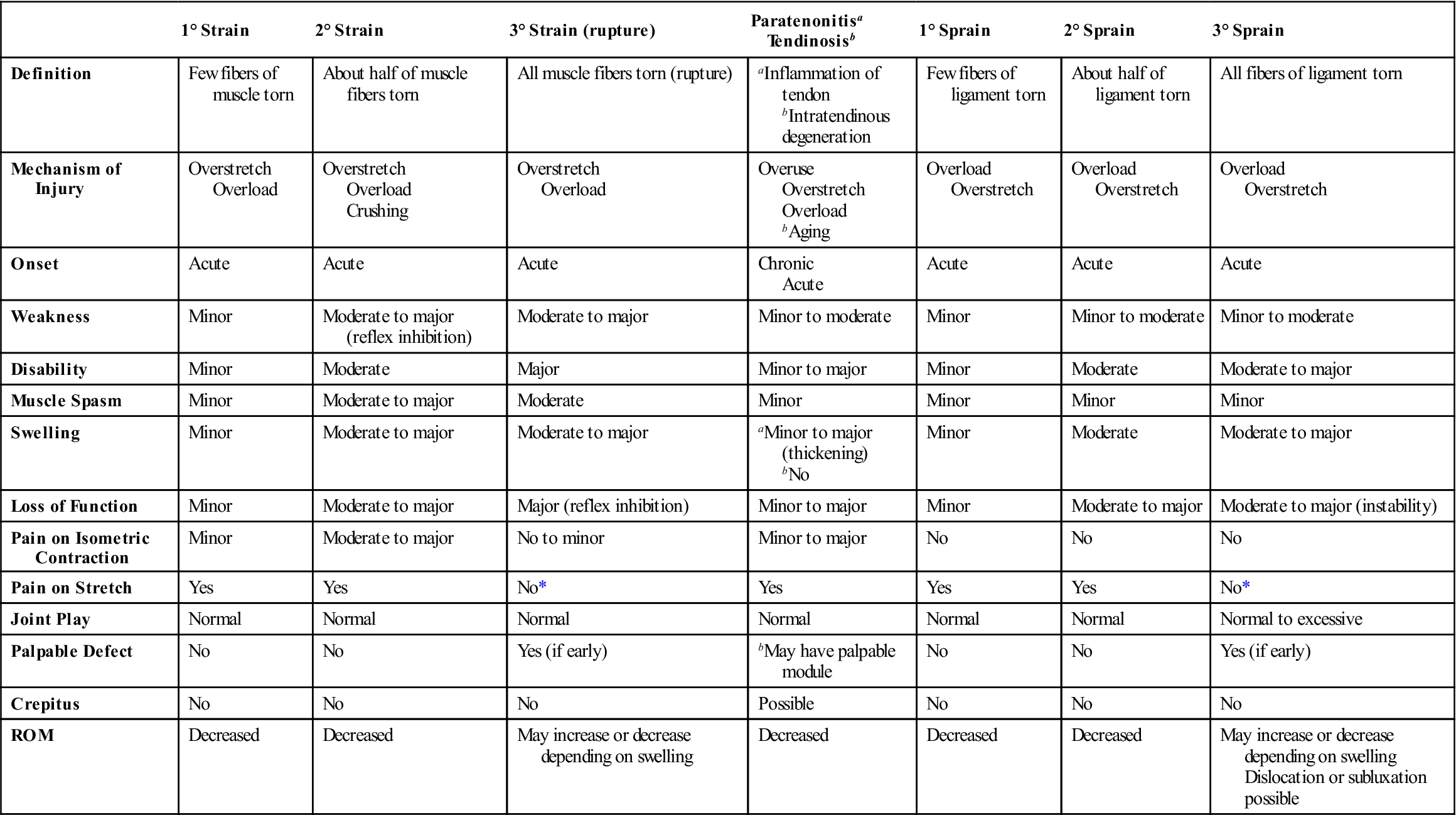

Contractile tissues may have tension placed on them by stretching or contraction.1 These structures include the muscles, their tendons, and their attachments into the bone. Nervous tissues and their associated sheaths also have tension put on them by stretching and pinching, as do inert tissues. Inert tissues include all structures that would not be considered contractile or neurological, such as joint capsules, ligaments, bursae, blood vessels, cartilage, and dura mater. Table 1-16 demonstrates differential diagnosis of injuries to contractile tissue (strains and paratenonitis) and inert tissue (sprains). Some examiners separate vascular tissues from the other inert tissues; however, for the most part, when doing a musculoskeletal examination, they can be grouped with the other inert tissues with the understanding that they do present their own unique signs and symptoms.

TABLE 1-16

Differential Diagnosis of Muscle Strains, Tendon Injury, and Ligament Sprains

| 1° Strain | 2° Strain | 3° Strain (rupture) | Paratenonitisa Tendinosisb | 1° Sprain | 2° Sprain | 3° Sprain | |

| Definition | Few fibers of muscle torn | About half of muscle fibers torn | All muscle fibers torn (rupture) | aInflammation of tendon bIntratendinous degeneration |

Few fibers of ligament torn | About half of ligament torn | All fibers of ligament torn |

| Mechanism of Injury | Overstretch Overload |

Overstretch Overload Crushing |

Overstretch Overload |

Overuse Overstretch Overload bAging |

Overload Overstretch |

Overload Overstretch |

Overload Overstretch |

| Onset | Acute | Acute | Acute | Chronic Acute |

Acute | Acute | Acute |

| Weakness | Minor | Moderate to major (reflex inhibition) | Moderate to major | Minor to moderate | Minor | Minor to moderate | Minor to moderate |

| Disability | Minor | Moderate | Major | Minor to major | Minor | Moderate | Moderate to major |

| Muscle Spasm | Minor | Moderate to major | Moderate | Minor | Minor | Minor | Minor |

| Swelling | Minor | Moderate to major | Moderate to major | aMinor to major (thickening) bNo |

Minor | Moderate | Moderate to major |

| Loss of Function | Minor | Moderate to major | Major (reflex inhibition) | Minor to major | Minor | Moderate to major | Moderate to major (instability) |

| Pain on Isometric Contraction | Minor | Moderate to major | No to minor | Minor to major | No | No | No |

| Pain on Stretch | Yes | Yes | No* | Yes | Yes | Yes | No* |

| Joint Play | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal to excessive |

| Palpable Defect | No | No | Yes (if early) | bMay have palpable module | No | No | Yes (if early) |

| Crepitus | No | No | No | Possible | No | No | No |

| ROM | Decreased | Decreased | May increase or decrease depending on swelling | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | May increase or decrease depending on swelling Dislocation or subluxation possible |

*Not if it is the only tissue injured; however, often with 3° injuries, other structures will suffer 1° or 2° injuries and be painful.

When doing movement testing, the examiner should note whether pain or restriction predominate. If pain predominates, the condition is more acute, and gentler assessment and treatment are required. If restriction predominates, the condition is subacute, or chronic, and more vigorous assessment and treatment can be performed.

Active Movements