CHAPTER 76 Primary Osteoarthritis: Ulnohumeral Arthroplasty

INTRODUCTION

Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow is now well recognized and readily treated. Even today, the studies to better understand the condition are limited. Articular cartilage changes at the distal humerus40 and proximal radius with aging have been observed and studied.15 More recent experience with this condition has clarified to some extent the etiology and presentation, but the greatest advances are in the treatment of this disease. *

INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

The existence of degenerative arthritis of the elbow has been recognized by orthopedic surgeons in the past, but the etiology was generally believed to be secondary to unrecognized or repetitive trauma. The radiographic characteristics have, however, been carefully delineated by Mianami et al in 1977.29 Furthermore, demographic studies have shown dramatic differences in the incidence of elbow arthritis in different races, but it is unclear if this is due to a genetic or an environmental influence.43 Smith50 clearly identified a condition that he termed osteoarthritis as a sequelae to trauma such as fracture-dislocation or “hard usage.” In fact, the condition as an overuse manifestation is rather well recognized,3,17,32 yet only brief references to the condition are noted in the standard texts.33,50 In addition to an increased awareness, there is some evidence that the actual incidence of the disease may be increasing.8

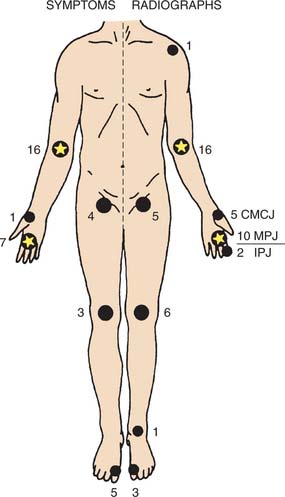

When discussed, it is thought to be related to a single or repetitive traumatic event or other predisposing conditions such as osteochondritis dissecans.21,50,57 We concur with this opinion as a cause, at least in some. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow has been reported as accounting for 1% to 2% of patients presenting with elbow arthritis.7,18 This is consistent with the observation that less than 5% of joint replacement is performed in patients with this diagnosis.24,37 Doherty and Preston10 reported an incidence of about 7% from a typical rheumatologic practice and was shown to be associated with other sites of involvement, especially of the hand (Fig. 76-1). Because of these features, recognition of the entity is still sometimes overlooked or misinterpreted as a post-traumatic condition.11

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Men are, by far, more commonly affected with this condition than women at a ratio of about 4 to 1.11,19,29,31,38 The age at initial presentation is about 50 years,10 but I and others have observed a surprising variation ranging from 20 to 65 years.31,38 Occupations or avocations involving the repetitive use of an extremity are the most common factors, being present in about 60% of patients. We have diagnosed this problem in persons with neuropathic conditions causing impaired ambulation and requiring continued use of crutches or a wheelchair. The dominant extremity is involved in about 80% to 90% of patients, and bilateral involvement is present in 25% to 60%.10,38 The radiohumeral joint is involved in about 85%, but it may not be symptomatic.8

Stiffness may be a dominant feature.10 Loss of extension is the most common problem prompting medical attention, but mild to occasional moderate pain is also commonly present. The characteristic pain is of terminal extension in almost all patients and of terminal flexion in about 50%. Less commonly, symptoms are present throughout the arc. The intensity of pain is mild to moderate, and only occasionally is the process described as severe. The radiohumeral joint may be symptomatic in flexion, extension, and rotation.

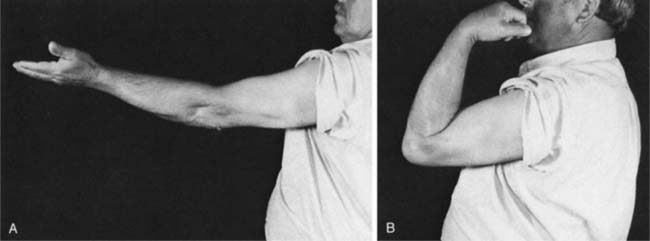

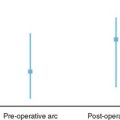

Consistent with these features, examination reveals an arc of motion that averages about 30 to 120 degrees (Fig. 76-2). Forearm rotation is not restricted or only minimally so because the radiohumeral joint is typically not severely involved. Because of excessive osteophyte formation, ulnar nerve irritation is observed in at least 10%31 and we suspect in a higher number if carefully examined. Ulnar nerve involvement should be specifically sought in the examination because it may influence treatment decisions and even long-term outcome.1

LABORATORY STUDIES

Because the diagnosis is not obvious owing to its relative infrequent occurrence, arthrocentesis, synovial biopsy, and arthroscopy have all been performed to diagnose this condition.11,39 When one is familiar with the disease, it comes as no surprise that all three of these diagnostic studies offer little if any added value.10,38 The roentgenographic study is diagnostic, and typically no other assessment is indicated or required. The sedimentation rate is normal.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

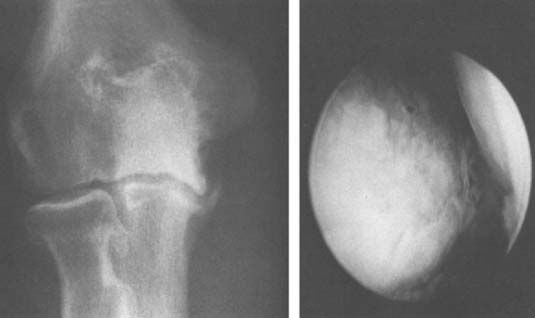

The roentgenographic features of this condition are classic and characteristic, maybe even monotonous. The characteristic of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is “marginal osteophyte formation.” Hence, the consistent routine anteroposterior and lateral roentgenograms reveal an anterior osteophyte of the coronoid and a posterior osteophyte of the olecranon process (Fig. 76-3).29 The anteroposterior view also shows a consistent finding of ossification and osteophyte formation in the olecranon or coronoid fossa (Fig. 76-4). In the later stages, no other study is required to make this diagnosis. However, tomography may show subtle osteophyte formation, the presence and location of loose bodies, and the size and extent of the osteophytes on the humerus and ulna (Fig. 76-5). Involvement of the radial head has been documented in about 85%.8 Bell and Minami et al2,31 have characterized the development of loose bodies as an integral feature of primary arthritis of the elbow. Special imaging studies are not needed and are of no value to diagnose this condition. A cubital tunnel view is sometimes obtained if the ulnar nerve shows signs of ulnar neuritis. These features do reflect the clinical expression and provide a guideline to treatment.

TREATMENT

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

Symptomatic treatment is appropriate, especially in the early stages because symptoms are slowly progressive and well tolerated. Although anti-inflammatory agents may be of use, by the time the patient sees a surgeon, the clinical findings and functional limitations usually justify some intervention. This is in contrast with the experience of others in which nonoperative treatment appears appropriate and adequate.10 In addition to anti-inflammatory agents, in some instances a cortisone injection may be of value. One study, however, demonstrated that the use of hyaluronic acid was not effective in 18 patients treated with hyaluronic acid with the diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow.54 The mean time to surgery from symptom onset is about 5 years. The most important feature of the initial treatment is to explain to the patient the cause of the pain and the natural history of the process, and to recommend activity modification. However, because this disorder is so often associated with one’s occupation, this advice usually goes unheeded or cannot be acted on. Avoiding pressure to the cubital tunnel is recommended if there are ulnar nerve symptoms.

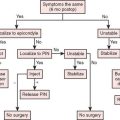

OPERATIVE TREATMENT

Several surgical options exist and are evoked depending on the dominant symptoms and radiographic change (Table 76-1). For the most part, débridement by arthroscopy or by arthrotomy is the treatment of choice, with or without ulnar nerve decompression. In some instances, symptomatic loose bodies will be the primary pathology or at least the primary complaint. Under these circumstances, simple arthroscopic removal of the loose bodies relieves the patient of their symptoms5,44 and, in some instances, may even improve motion up to 15 degrees.44

TABLE 76-1 General Relationship of Major Symptoms with Preferred Treatment

| Dominant Symptom | Surgical Technique |

|---|---|

| Loose body | Arthroscopy |

| Extension loss | |

| Mild | Arthroscopy*/Column |

| Moderate | Column |

| Flexion loss | Column |

ARTHROSCOPY

Arthroscopic Management

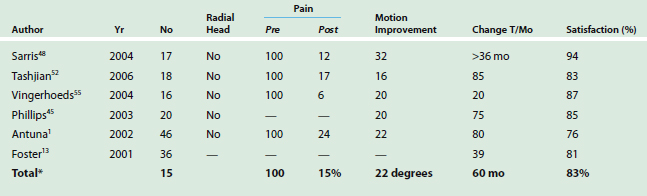

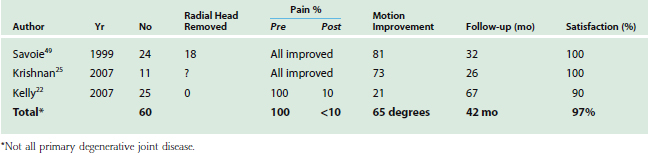

Arthroscopic débridement of the elbow is discussed in Chapters 38 to 40; however, there have been a number of reports specifically discussing arthroscopic débridement in the face of primary osteoarthritis (Fig. 76-6).16,23,28 These studies are summarized in Table 76-2. Although the sample is relatively small (60 patients) with a mean follow-up of just more than 3 years, it is impressive that more than 90% of patients expressed satisfaction with relief of pain and the improved arc of motion in these recent studies is greater than 60 degrees. Hence, arthroscopic débridement for primary osteoarthritis is emerging as a viable treatment option. In our opinion, the key elements to consider this option are

TABLE 76-2 Scope: Summary of the Recent Literature Regarding Arthroscopic Treatment for Primary Osteoarthritis

Technique

The technique for removal of loose bodies and for osseous and capsular débridement are described in detail in Chapters 38 to 40.

Results

A summary of arthroscopic intervention is shown in Table 76-2. Two early reports by Redden and Stanley46 and Ogilvie-Harris et al40 provide the results of 12 and 21 patients, respectively. Overall, a successful result from a similar débridement technique is reported for all 33 patients with adequate surveillance. Improved results are observed in the more recent studies. The benefits include universal relief of most or some pain, elimination of locking, and slight improvement in motion at about 2 years.40,46 A rapid recovery was noted in both studies with minimal complications. However, the potential for significant nerve injury, especially with adjunctive débridement must be considered.

Open Joint Débridement

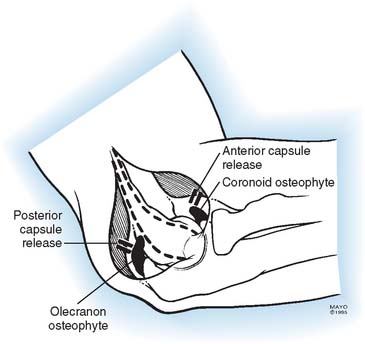

A “house cleaning” procedure has long been recommended for arthritic elbow disease.50 A safe and effective débridement procedure was originally described by Outerbridge and popularized and first reported by Kashiwagi in 1978. Simply stated, this débridement procedure removes bone from the ulnar and humeral articular margins, altering the joint and justifying the term arthroplasty. Modification of this technique by exposure, and trephine débridement, descriptively termed ulnohumeral arthroplasty (UHA), is my preferred treatment for the selected patient.38 Subsequently, there have been a number of articles from several sources documenting satisfactory outcomes of various débridement procedures. Most of these are termed the UHA, which is our preference or the O-K arthroplasty after the originators Outerbridge and Kashiwagi. I have also combined the UHA with the column procedure when an anterior débridement and capsular release is desirable (Fig. 76-7). In any event, Table 76-3 summarizes the outcomes of six studies comprising more than 160 patients.

Ulnohumeral Arthroplasty

Technique

A straight incision 4 cm distal and 8 cm proximal to the olecranon is made over the posterior aspect of the elbow. A medial flap is elevated and the ulnar nerve decompressed in situ. We only rarely translocate the nerve in this circumstance.

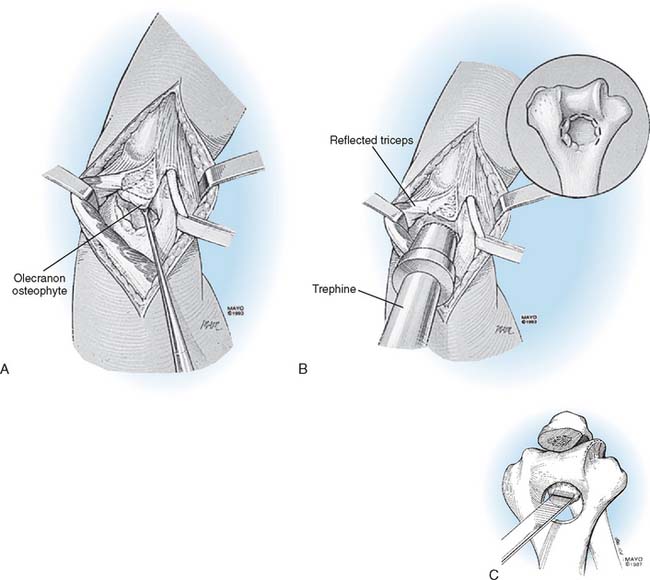

The medial one half of the triceps attachment is elevated or the triceps is simply split in the mid line (Fig. 76-8).

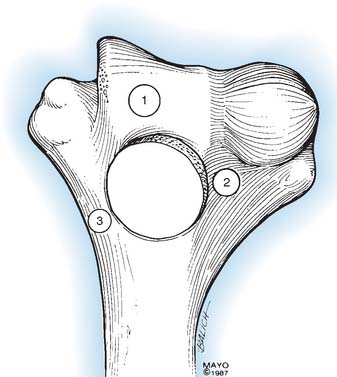

Note: The placement of the trephine is worthy of emphasis. If the trephine is placed too distal, the competence of the trochlea may be impaired (Fig. 76-9); if it is placed too lateral, the capitellum may be violated; and if it is placed too medial, the medial column may be weakened.

I have yet to remove the radial head as an adjunct to this procedure and agree with Tsuge and Mizuseki53 that this is to be avoided if at all possible.

Postoperative Management

The postsurgical treatment program is similar to that for those undergoing release for a post-traumatic stiff joint33 (see Chapter 32). On the day of surgery, the patient is given a brachial plexus block with a constant infusion of local analgesic14 (see Chapter 8). The extremity is placed in a continuous motion machine and is elevated, and a passive arc of motion is aggressively established. The analgesic block is discontinued after approximately 24 hours, and continuous passive motion is monitored for a second day. Active motion is allowed to the greatest extent possible. A hinged splint is applied, and the patient is given detailed instructions with regard to the use of the splint to maintain both flexion and extension (see Chapter 11).35

RESULTS

Minami et al31 updated the results of the original O-K arthroplasty in 44 elbows that were observed for 8 to 16 years. With a mean surveillance of more than 10 years, 55% had no or minimal pain. Appropriately, 10% deteriorated since the original report with a mean surveillance of about 5 years.30 An additional 61% had partial relief of pain. Overall, 76% of patients had improved flexion and 55% had improved extension after surgery. With subsequent assessment, the mean arc had decreased to 32 to 122 degrees, representing a 17-degree loss over time (Fig. 76-10).

More recent reports are summarized in Table 76-3. Residual pain is present in about 15% of patients. Only a modest improvement in the arc of approximately 20 degrees of motion was observed. At a mean follow-up of 5 years, approximately 85% of patients were satisfied with the procedure. Furthermore, there has been one specific comparison of 18 patients with the open débridement and 26 patients undergoing arthroscopic joint débridement.6 At approximately 3 years’ follow-up, these investigators conclude interestingly that the pain relief seems to be superior after the arthroscopic procedure; however, at least in their hands, the postoperative arc of motion had increased more in the open than in the arthroscopic patients. We would conclude by saying that both techniques are viable, but the above-mentioned principles should be kept in mind for the arthroscopic intervention.

MAYO EXPERIENCE: ULNOHUMERAL ARTHROPLASTY

Initial results of Minami and Ishii parallel my preliminary and current experience.38 Mansat et al27 have reviewed the Mayo experience using this procedure in seven patients with osteoarthritis. A mean arc of 43 to 108 degrees improved postoperatively to 21 to 124 degrees, a 38-degree improvement. Pain relief was reliably achieved in all (Fig. 76-11). This technique can be an additional feature to the ulnohumeral débridement described below.

RECENT UPDATE

In 2002 our experience with 46 elbows was reviewed by Antuna et al1 with a mean follow-up of 80 months (2-14 years). It was documented that an improvement of 22 degrees occurred in the flexion arc, with an average arc at follow up of 30 to 135 degrees. Seventy-five percent of the elbows were not painful, reflecting the 75% that were considered satisfactory, a mean follow-up of 7 years. One major finding in this group was that the presence of ulnar nerve symptoms that was not addressed at the time of the débridement significantly and adversely affected the outcome. As a result of this experience, we have aggressively evaluated patients for the presence of ulnar neuropathy and have addressed this appropriately at the time of surgery.

Complications

If the technical points are understood and followed, the complication rate is very low, which is uncommon for most reconstructive procedures at the elbow. The ulnar nerve is at greatest risk. Recurrence of symptoms occur in 20% at 10 years.31 Recurrence of the radiographic changes may develop in as many as 50% of patients after 5 years.19,20,29,30 (Fig. 76-12).

EXTENDED DÉBRIDEMENT

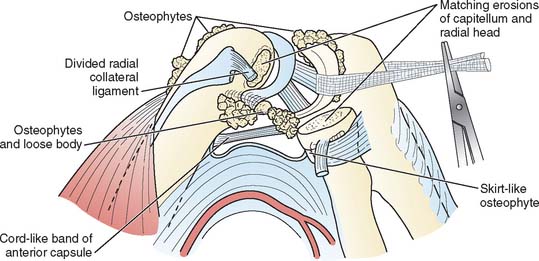

In addition to the classic O-K or UHA, other authors have employed variations of an open débridement procedure.42,56 If the patient is too young to undergo prosthetic replacement, an aggressive extensile débridement as recommended by Tsuge,53 Oka,41 and others may be considered.

Procedure

Extensile Débridement (Tsuge Technique)

Technique.

This débridement is essentially that performed with interposition arthroplasty (see Chapter 69) but is limited to release and débridement.

The patient is supine, and a posterior incision is performed. The nerve is decompressed and the triceps reflected, generally from medial to lateral. We prefer notto release the ligaments but this is done by Tsuge (Fig. 76-13). The capsule is released, and the osteophytes are removed. The marginal osteophyte of the radial head is removed only if symptomatic. Removal of the entire radial head is avoided.

ULNAR NERVE

PROSTHETIC REPLACEMENT

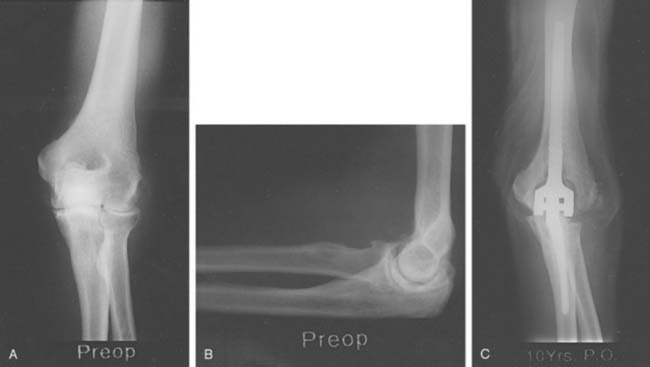

Kozak et al24 reported our experience of five patients with primary osteoarthritis treated by joint replacement (Fig. 76-14). The mean age was 68 years. All five were doing well at final assessment, with a mean flexion arc of 30 to 125 degrees averaging 5 years after surgery. Yet, four had significant complications, such as fracture of the implant, ectopic bone, implant wear debris, and transient ulnar nerve symptoms. This topic is reviewed in detail in Chapter 60.

Since the last edition, there have been few indications for replacement in our practice. Espag et al. did report 11 instances of primary degenerative arthritis treated by the Souter-Strathclyde implant with a mean surveillance of 68 months. Evidence of loosening was present in three humeral and two ulnar components, one of which was revised during the preparation of the manuscript. These authors also noted two neuropraxias of the ulnar nerve and overall believed that this was a satisfactory outcome in nine of the 11 cases.12

1 Antuna S.A., Morrey B.F., Adams R.A., O’Driscoll S.W. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: Long-term outcome and complications. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84A:2168.

2 Bell M.S. Loose bodies in the elbow. Br. J. Surg. 1975;62:921.

3 Bovenzi M., Fiorito A., Volpe C. Bone and joint disorders in the upper extremities of chipping and grinding operators. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 1987;59:189.

4 Cheung E.V., Adams R., Morrey B.F. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow: Current treatment options. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2008;16:77.

5 Clasper J.C., Carr A.J. Arthroscopy of the elbow for loose bodies. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2001;83:34.

6 Cohen A.P., Redden J.F., Stanley D. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow. A comparison of open and arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:701.

7 Collins D.H. The Pathology of Articular Cartilage in Spinal Disease. London: Edward Arnold Co., 1949.

8 Delal S., Bull M., Stanley D. Radiographic changes at the elbow in primary osteoarthritis: A comparison with normal aging of the elbow joint. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:358.

9 Debono L., Mafart B., Jeusel E., Guipert G. Is the incidence of elbow osteoarthritis underestimated? Insights from paleopathology. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:397.

10 Doherty M., Preston B. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1989;48:743.

11 Doherty M., Watt I., Dieppe P.A. Influence of primary generalized osteoarthritis on development of secondary osteoarthritis. Lancet. 1983;2:8.

12 Espag M.P., Back D.L., Clark D.I., Lunn P.G. Early results of the Souter-Strathclyde unlinked total elbow arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85B:351.

13 Forster M.C., Clark D.I., Lunn P.G. Elbow osteoarthritis: Prognostic indicators in ulnohumeral debridement—the Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:557.

14 Gaumann D.M., Lennon R.L., Wodel D.J. Continuous axillary block for postoperative pain management. Reg. Anesth. 1988;13:77.

15 Goodfellow J.W., Bullough D.G. The pattern and aging of articular cartilage in the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1967;49B:175.

16 Gramstad G.D., Galatz L.M. Management of elbow osteoarthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88A:421.

17 Hellmann D.B., Helms C.A., Genant H.K. Chronic repetitive trauma: A cause of atypical degenerative joint disease. Skeletal Radiol. 1983;10:236.

18 Huskisson E.C., Dieppe P.A., Tucker A.K., Cannell L.B. Another look at osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1979;38:423.

19 Kashiwagi D. Intra-articular changes of the osteoarthritic elbow, especially about the fossa olecrani. Jpn. Orthop. Assoc. 1978;52:1367.

20 Kashiwagi D. Outerbridge Kashiwagi arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow in the elbow joint. In: Kashiwagi D., editor. Proceedings of the International Congress, Kobi, Japan. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1986.

21 Kelley W.N., Harris E.D., Ruddy S., Sledge C.P., editors. Textbook of Rheumatology, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1989.

22 Kelly E.W., Bryce R., Coghlan J., Simon B. Arthroscopic debridement without radial head excision of the osteoarthritic elbow. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:151.

23 Kim S.J., Shin S.J. Arthroscopic treatment for limitation of motion of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 2000;375:140.

24 Kosak K., Morrey B.F. Prosthetic replacement for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. J. Arthroplasty. 1998;13:837.

25 Krishnan S.G., Harkins D.C., Pennington S.D., Harrison D.K., Burkhead W.Z. Arthroscopic ulnohumeral arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the elbow in patients under 50 years of age. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:443.

26 Lo G.H., LaValley M., McAlindon T., Felson D.T. Intraarticular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. J. A. M. A. 2003;290:3115.

27 Mansat P., Morrey B.F. The “column procedure” a limited surgical approach for the treatment of stiff elbows. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:1603.

28 McLaughlin R.E.2nd, Savoie F.H.3rd, Field L.D., Ramsey J.R. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow due to primary radiocapitellar arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:63.

29 Minami N.M. Roentgenological studies of osteoarthritis of the elbow joint. Jpn. Orthop. Assoc. 1977;51:1223.

30 Minami N.M., Ishii S. Outerbridge Kashiwagi arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow joint. In: Kashiwagi D., editor. Proceedings of the International Congress, Kobi, Japan. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1986.

31 Minami M., Kato S., Kashiwagi D. Outerbridge-Kashiwagi’s method for arthroplasty of osteoarthritis of the elbow. 44 elbows followed for 8-16 years. J. Orthop. Sci. 1996;1:11.

32 Mintz G., Fraga A. Severe osteoarthritis of the elbow in foundry workers. Arch. Environ. Health. 1973;27:78.

33 Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1985.

34 Morrey B.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Instr. Course Lect. 1986;35:102.

35 Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: Operative treatment including distraction arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:601.

36 Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: Operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:601.

37 Morrey B.F. Elbow replacement arthroplasty: Patient selection. In: Morrey B.F., editor. Joint Replacement Arthroplasty. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1991:669.

38 Morrey B.F. Primary arthritis of the elbow treated by ulno-humeral arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. (Br). 1992;74B:409.

39 O’Driscoll S., Morrey B.F. Elbow arthroscopy: A critical assessment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:84.

40 Ogilvie-Harris D.J., Gordon R., MacKay M. Arthroscopic treatment for posterior impingement in degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:437.

41 Oka Y. Debridement arthroplasty for osteoarthrosis of the elbow: 50 patients followed a mean of 5 years. Acta Orthop. Scand. 2000;71:185.

42 Oka Y., Ohta K., Saitoh I. Debridement arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1998;351:127.

43 Ortner D.J. Description and classification of degenerative bone changes in the distal joint surface of the humerus. Am. J. Phys. Anthrop. 1968;28:139.

44 Ozbaydar M.U., Tonbul M., Altan E., Yalaman O. Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic loose bodies in osteoarthritic elbows. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2006;40:371.

45 Phillips N.J., Ali A., Stanley D. Treatment of primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. A long-term follow-up. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85B:347.

46 Redden J.F., Stanley D. Arthroscopic fenestration of the olecranon fossa in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:14.

47 Salk R.S., Chang T.J., D’Costa W.F., Soomekh D.J., Grogan K.A. Sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the ankle: A controlled, randomized, double blind pilot study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88A:295.

48 Sarris I., Riano F.A., Goebel F., Goitz R.J., Sotereanos D.G. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty: results in primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 2004;420:190.

49 Savoie F.H.3rd, Nunley P.D., Field L.D. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, technique, and results. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214.

50 Smith F.M. The Elbow, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1972.

51 Stanley D., Winsor G. A surgical approach to the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72B:728.

52 Tashjian R.Z., Wolf J.M., Ritter M., Weiss A.P., Green A. Functional outcomes and general health status after ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:357.

53 Tsuge K., Mizuseki T. Debridement arthroplasty for advanced primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Results of a new technique used for. 29 elbows. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76B:641.

54 van Brakel R.W., Eygendaal D. Intra-articular injection of hyaluronic acid is not effective for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1199.

55 Vingerhoeds B., Degreef I., De Smet L. Debridement arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow (Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure). Acta Orthop. Belg. 2004;70:306.

56 Wada T., Isogai S., Ishii S., Yamashita T. Debridement arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86A:233.

57 Wadsworth T.G. The Elbow. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1982.