Chapter 38 Primary Osteoarthritis of the Elbow

Introduction

Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is a relatively uncommon condition mainly affecting middle-aged men. It is characterized by wear of the articular cartilage together with new bone formation at the joint surfaces.1 The condition is normally progressive, although the speed of progression is variable. In the general population it has a prevalence of between 1.3 and 2.0%,2,3 although Doherty and Preston working in a rheumatological clinic noted a prevalence of 7%.4

Background/aetiology

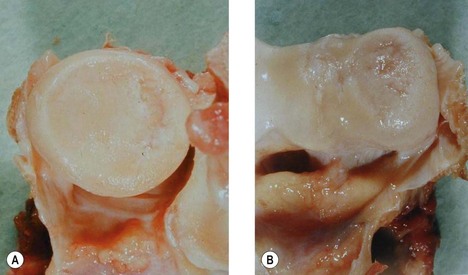

The natural history of articular cartilage changes within the elbow has been investigated by Goodfellow and Bullough.5 They examined 28 elbow joints retrieved at autopsy in subjects aged 18–88 years. They noted that with increasing age the radiocapitellar joint almost invariably showed degenerative change with a posteromedial radial head ulcer (Fig. 38.1A,B). Associated with this was an area of linear ulceration of the humeral crest between the trochlea and the capitellum. By contrast the cartilage of the ulnar-trochlear joint rarely showed evidence of degeneration. In older subjects grooves in the articular cartilage of this articulation were seen, although these did not expose the underlying bone. It was suggested that the differences in the pattern of wear between the radiocapitellar and ulnar-trochlear joints were related to the fact that the radiocapitellar joint has a combination of flexion, extension and rotational movements, whereas the ulnar-trochlear joint has only flexion and extension.

Murato et al6 noted similar changes in the elbow with ageing and concluded that there was a progression of change from normal ageing to the development of elbow osteoarthritis. They found that the degenerative change in the radiocapitellar joint was always more advanced than in the ulnar-trochlear joint.

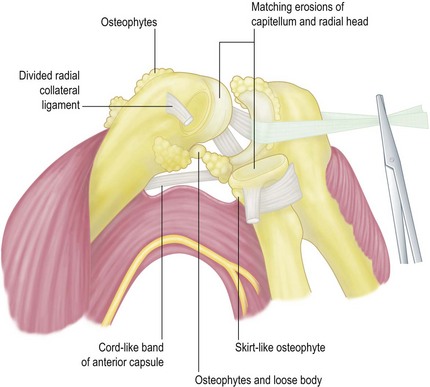

Kashiwagi7 and Tsuge and Mizuseki8 noted erosion of the radial head with reciprocal loss of cartilage over the capitellum. Osteophytes occur around the radial head, but are predominantly seen at the tip of the olecranon and coronoid process. They may also be present around the olecranon and coronoid fossae.9 Osteophytes involving the medial aspect of the joint may also compress the ulnar nerve resulting in symptoms of ulnar neuritis. Bell10 first reported the presence of loose bodies within the elbow and Morrey11 has suggested that these occur in up to 50% of patients with elbow osteoarthritis. These loose bodies may be single or multiple and can be found in any compartment of the joint.

Thickening of the olecranon fossa membrane was originally noted by Kashiwagi7 when he performed the Outerbridge–Kashiwagi procedure. More recently a histological study has shown that the anterior and posterior cortices, together with the intramedullary bone of the olecranon fossa membrane, are all thickened in this condition.12

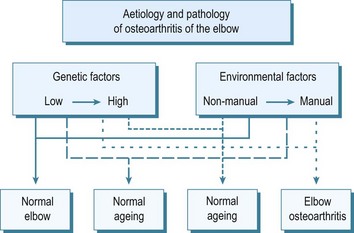

The aetiology of elbow osteoarthritis is not fully understood. Repetitive trauma is undoubtedly an important factor, but it is probable that other influences particularly genetic factors are also relevant in the development of this condition (Fig. 38.2).

Figure 38.2 Proposed interaction of genetic and environmental factors in the development of osteoarthritis of the elbow.

Holtzmann13 in a study of heavy manual workers suggested that the use of pneumatic tools might be an important predisposing influence. This view was supported by Rostock,14 who found that miners using pneumatic boring equipment experienced osteoarthritis of the elbow more commonly than shoulder or wrist osteoarthritis. Lawrence15 noted that 31% of miners using pneumatic drills for more than1 year developed elbow osteoarthritis compared with only 16% who had not drilled. Other authors, however, have failed to show an association with this type of work.16,17

Of greater significance was the finding from Lawrence’s study15 that in miners the elbow was the third most frequently affected joint with osteoarthritis after the spine and knee. Lawrence concluded that elbow osteoarthritis was a feature of all types of heavy manual work. More recently Stanley3 has shown a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of elbow osteoarthritis in men undertaking heavy manual work compared with those doing non-manual tasks (p = 0.016).

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Clinical presentation

Investigations

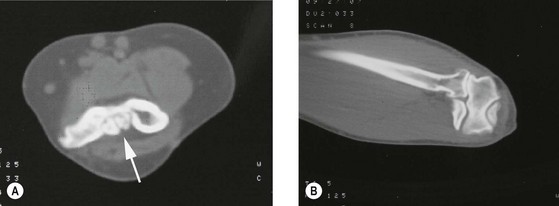

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are usually the only investigations required to make the diagnosis (Fig. 38.3). These usually show the characteristic features of the condition with osteophytes at the tip of the olecranon and coronoid process, narrowing of the radiocapitellar joint space, radial head osteophytes, loss of definition of the outline of the olecranon fossa due to thickening of the interfossa membrane and loose body formation.9 When multiple loose bodies are present, computed tomography allows confirmation of the number of loose bodies within the joint, together with the location and identifies the extent of osteophyte formation (Fig. 38.4).

Treatment options

It is obviously important that all patients are made aware of their diagnosis and that this is the cause of their symptoms. Those with minor complaints may find conservative management beneficial. The use of simple analgesics or non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs may relieve symptoms, and on occasion an intra-articular steroid injection can also be of benefit.4

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Arthroscopic debridement

The arthroscopic treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow is becoming increasingly popular. It is, however, dependent on the surgeon having a detailed anatomical knowledge of the elbow and appropriate arthroscopic expertise. These techniques have been used for the removal of loose bodies,18 debridement of osteophytes19 and for performing the ulnohumeral arthroplasty arthroscopically.20,21 The surgical set up and techniques available are beyond the remit of this chapter. For a more detailed description and discussion the reader is referred to Chapter 39.

Open debridement procedures

Outerbridge–Kashiwagi procedure/ulnohumeral arthroplasty

Kashiwagi22 reported an open debridement procedure for osteoarthritis of the elbow that he attributed to Outerbridge and described as the Outerbridge–Kashiwagi or OK method. The operation allowed the removal of loose bodies and the excision of osteophytes and was stated to relieve pain and improve flexion. Using this technique good results were obtained by both Minami and Ishii23 and Stanley and Winson.24 The procedure was later modified by Morrey,25 who recommended the use of a bone trephine for fenestration of the olecranon fossa membrane in order to reduce bone debris. He named the operation ulnohumeral arthroplasty.

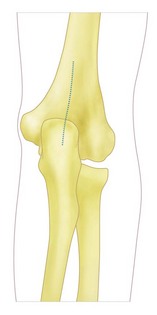

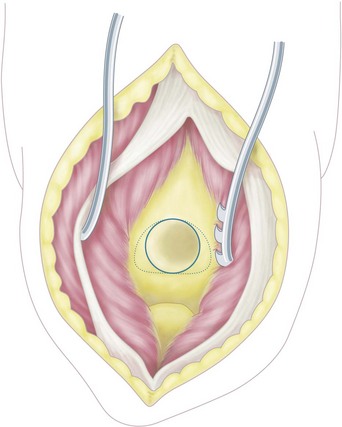

The operation is performed under tourniquet control with the patient supine on the operating table and with a sandbag under the ipsilateral shoulder. With the arm across the chest an 8 cm midline incision is made extending proximally from the tip of the olecranon (Fig. 38.5). The incision is deepened and the triceps is split in the line of its fibres. The posterior capsule is then opened and any loose bodies in this compartment are removed (Fig. 38.6). Osteophytes at the tip of the olecranon and around the olecranon fossa are excised. A bone trephine of approximately the same size as the olecranon fossa is then used to fenestrate the thickened olecranon fossa membrane allowing access to the anterior compartment of the elbow (Fig. 38.7). By flexion and extension of the elbow anterior loose bodies will present themselves at the fenestrated fossa and can be easily removed. In addition by maximal flexion of the elbow osteophytes at the tip of the coronoid process can be excised through the fenestration using a fine osteotome. The elbow is then thoroughly washed out and the wound closed over a suction drain. A dressing of orthopaedic gauze, wool and crepe is applied and the arm is supported in a broad arm sling. The drain is removed within 24 hours and the dressing reduced. The patient is then encouraged to undertake progressive range of movement and strengthening exercises.

Figure 38.7 The olecranon fossa membrane has been fenestrated allowing access to the anterior compartment of the elbow.

Morrey25 uses a more aggressive postoperative rehabilitation regimen with a continuous brachial plexus block for 1–3 days together with the use of continuous passive motion. In addition, active movement is encouraged and the patient is provided with a hinged splint to maintain both flexion and extension.26 Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs will confirm that appropriate debridement has been achieved (Fig. 38.8).

Tsuge debridement procedure

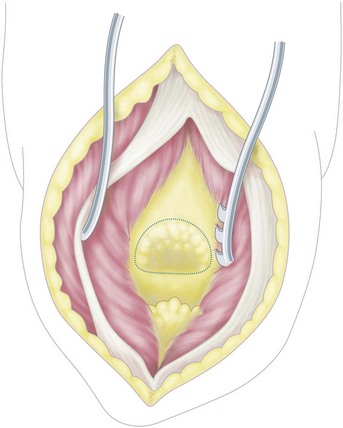

Tsuge and Mizuseki27 described a more extensive debridement procedure for advanced primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Via a posterior incision the ulnar nerve is identified and protected and the extensor mechanism reflected medially. The radial collateral ligament and the posterior part of the ulnar collateral ligament are divided and the joint dislocated (Fig. 38.9). Loose bodies are removed and osteophytes excised. The shallow olecranon, coronoid and radial fossae are deepened with a burr and the anterior capsule released to improve extension. If there is restricted rotation the radial head can be trimmed and reshaped to improve pronation and supination. Postoperatively, continuous passive motion is used for 7 days.

Ulnar nerve surgery

Compression of the ulnar nerve is not uncommon with osteoarthritis of the elbow and may result from medial joint osteophytes or thickening of the fascia overlying the cubital tunnel. The clinical diagnosis and site of compression should be confirmed electromyographically after which decompression of the nerve should be undertaken. For the techniques of ulnar nerve decompression, the reader is referred to Chapter 31.

Total elbow arthroplasty

Although total elbow arthroplasty has been shown to be an effective treatment option in rheumatoid arthritis, the indications for its use in osteoarthritis are more limited.28 The procedure should not be undertaken in young adults who wish to perform manual tasks and is only suitable for those over the age of 65 who have low activity levels, pain throughout the range of movement and in whom all other treatment options have failed. In addition if a total elbow arthroplasty is contemplated the patient must accept a lifetime ban on lifting weights of more than 4.5 kg (10 lb) or repetitive lifting of more than 1 kg (2 lb).29

Surgery is performed under tourniquet control. The patient is positioned either supine with a sandbag under the ipsilateral shoulder and with the arm across the chest or, as is my preference, with the patient lateral, the arm horizontal and with the forearm hanging vertically. A posterior skin incision is made centred at the tip of the olecranon and skin flaps elevated to allow identification and superficial decompression of the ulnar nerve. The nerve is then mobilized to enable the arthroplasty to be performed safely or, alternatively, formally anteriorly transposed. Several surgical approaches to the elbow joint have been reported and a number of implants utilized. Further information is given in Chapter 43. Essentially the elbow can be exposed using a triceps splitting, triceps reflecting or triceps sparing approach. The elbow is then dislocated and bone resection undertaken depending on the type of arthroplasty being inserted.

Outcome including literature review

Arthroscopy

The early results of arthroscopic debridement of the osteoarthritic elbow have been encouraging19,20 and more recent studies have shown reduction in pain, together with improved range of movement and patient satisfaction.21,30 Arthroscopic ulnohumeral arthroplasty has been shown to reduce elbow pain but has not always shown an improvement in range of movement.20 If, however, additional arthroscopic anterior and posterior capsular releases are performed, some improvement in range of movement can be expected.31

Debate exists as to whether excision of the radial head should be part of the arthroscopic procedure. Kelly et al30 advised against it whereas McLaughlin et al32 noted better outcomes when radial head excision alone was performed than when it was combined with ulnohumeral arthroplasty.

Open debridement procedures

Outerbridge–Kashiwagi procedure/ulnohumeral arthroplasty

Minami et al33 reported their experience of 44 osteoarthritic elbows that had been treated with Outerbridge–Kashiwagi arthroplasty and followed for 8–16 years. At a mean follow-up of 10 years 55% had no or minimal pain, 76% had improved flexion and 55% improved flexion. Phillips et al34 reviewed 20 patients at an average of 75 months postoperatively and noted that although there was some evidence of progressive closure of the olecranon fossa fenestration, this did not appear to affect the clinical outcome. Antuna et al35 reviewed 46 elbows at a mean follow-up of 80 months. Seventy-five per cent were considered to have had a satisfactory outcome. This study did, however, identify that patients with ulnar nerve symptoms that were not addressed at the initial debridement procedure had a less satisfactory outcome.

Cohen et al36 compared the results of arthroscopic and open debridement of the osteoarthritic elbow. At a follow-up of approximately 3 years, those patients undergoing arthroscopic surgery had superior pain relief whereas those who had open surgery had a better range of movement.

Tsuge debridement procedure

In 29 elbows, Tsuge and Mizuseki27 reported an average gain in range of movement of 34° at a mean follow-up of 64 months. Grip strength and pain relief were also improved in most patients.

Total elbow arthroplasty

Kozak et al37 reported their experience of total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of five patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow. At an average postoperative follow-up of 5 years the mean arc of flexion and extension was 85°. One of the two patients treated with an unlinked prosthesis had an unsatisfactory outcome but those treated with a linked prosthesis were considered to be doing well. Naqui et al38 reported their results with an unlinked implant with an average follow-up of almost 5 years. In this series there is a significant reduction in pain and improvement in movement and function. At follow-up no cases had been revised and there was no evidence of any significant radiolucency. Espag et al39 treated 11 osteoarthritic elbows (10 patients) using the unlinked Souter–Strathclyde prosthesis. At a mean follow-up of 68 months, seven patients were pain-free and three had persistent occasional pain especially on repetitive movement. The mean flexion/extension arc increased from 69° to 107°.

Complications of treatment

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy of the elbow has a higher complication rate than any other joint arthroscopic procedure. This is related to its complex anatomy and in particular the close proximity of neurovascular structures to the arthroscopic portals. The most common complication is transient nerve palsy, which occurs in up to 14% of reported series.30–32,40–42 Less frequent complications include infection, stiffness and myositis ossificans.

Open debridement procedures

Complications of open debridement procedures again include ulnar nerve entrapment and neuropraxia,35,43 triceps rupture44 with a reoperation rate of 8%.43 Wada et al45 noted a recurrence of olecranon and coronoid fossae osteophytes in all patients followed for 10 years or more after ulnohumeral arthroplasty. However, a correlation between radiographic signs of recurrence and functional outcome has not been firmly established. Finally Hearnden et al44 while confirming the improvement in pain relief and range of motion, noted that both diminished with time.

Total elbow arthroplasty

Kosak et al37 in their five osteoarthritic patients treated by total elbow arthroplasty noted complications that included implant wear and a fracture of one of the prostheses.

Espag et al39 also noted complications using the unlinked Souter–Strathclyde prosthesis. At a mean follow-up of 68 months, radiological evidence of loosening was seen around three humeral and two ulnar components, one of which required revision at 97 months.

1 Sokloff L. The biology of degenerative joint disease. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1969.

2 Collins DH. Incidence of cartilage changes and osteoarthritis in joints at different ages in the pathology of articular and spinal diseases. London: Edward Arnold; 1949.

3 Stanley D. Prevalence and aetiology of symptomatic elbow osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:386-389.

4 Doherty M, Preston B. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:743-747.

5 Goodfellow JW, Bullough PG. The pattern of ageing of the articular cartilage of the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1967;49:175-181.

6 Murato H, Ikuta Y, Murakami T. Anatomic investigation of the elbow joint with special reference to ageing of the articular cartilage. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2:175-181.

7 Kashiwagi D. Osteoarthritis of the elbow joint – intraarticular changes and the special operative procedure, Outerbridge-Kashiwagi method (O-K method). In: Kashiwagi D, editor. Elbow Joint. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers BV (Biomedical Division); 1985:177-188.

8 Stanley D. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. In: Stanley D, Kay NRM, editors. Surgery of the Elbow Practical and Scientific Aspects. London: Arnold; 1998:354-364.

9 Delal S, Bull M, Stanley D. Radiographic changes at the elbow in primary osteoarthritis: a comparison with normal ageing of the elbow joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:358-361.

10 Bell MS. Loose bodies in the elbow. Brit J Surg. 1975;62:921-924.

11 Morrey BF. Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: ulnohumeral arthroplasty. In: Morrey BF, editor. The Elbow and its Disorders. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:799-808.

12 Suvarna SK, Stanley D. The histological changes of the olecranon fossa membrane in primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:355-357.

13 Holtzmann F. Erkrankingen Durch Arbeiten Mit Pressluftwerkzeugen. Zentralb Gewerbehygiene Unfallverhutung. 1929;50:1002-1003.

14 Rostock P. Gelenkschaden Durch Arbeiten Mit Pressluftwerkzeugen und Andere Schwere. Rorperliche Arbeit Medizinische Klink. 1936;11:341-343.

15 Lawrence JS. Rheumatism in coal miners. Brit J Ind Med. 1955;12:249-261.

16 Hunter D, McLaughlin AIG, Perry KMA. Clinical effects of the use of pneumatic tools. Br J Ind Med. 1945;2:10-16.

17 Burke MJ, Fear EC, Wright V. Bone and joint changes in pneumatic drillers. Ann Rheum Dis. 1977;36:276-279.

18 O’Driscoll S, Morrey BF. Arthroscopy of the elbow: a critical assessment. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1992;74:84-94.

19 Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Gordon R, MacKay M. Arthroscopic treatment for posterior impingement in degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:437-443.

20 Redden JF, Stanley D. Arthroscopic fenestration of the olecranon fossa in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:14-16.

21 Krishnan SG, Harkins DC, Pennington SD, et al. Arthroscopic ulnohumeral arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the elbow in patients under 50 years of age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:443-448.

22 Kashiwagi D. Intra-articular changes of the osteoarthritic elbow, especially about the fossa olecrani. J Jap Orthop Assoc. 1978;52:1367-1382.

23 Minami M, Ishii S. Outerbridge-Kashiwagi arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the elbow. In: Kashiwagi D, editor. Elbow Joint. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers BV (Biomedical Division); 1985:189-196.

24 Stanley D, Winson IG. A surgical approach to the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1990;72:728-729.

25 Morrey BF. Primary arthritis of the elbow treated by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1992;74:409-413.

26 Morrey BF. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: Operative treatment including distraction arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1990;72:601-618.

27 Tsuge K, Mizuseki T. Debridement arthroplasty for advanced primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Results of a new technique used for 29 elbows. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1994;76:641-646.

28 Kraay MJ, Figgie MP, Inglis AE, et al. Primary semi-constrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1994;76:636-640.

29 Cheung EV, Adams R, Morrey BF. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow: current treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:77-87.

30 Kelly EW, Bryce R, Coghlan J, et al. Arthroscopic debridement without radial head excision of the osteoarthritic elbow. Arthroscopy. 2007;25:151-156.

31 O’Driscoll SW. Arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritis of the elbow. Orthop Clin N Am. 1995;26:691-706.

32 McLaughlin RE2nd, Savoie FH3rd, Field LD, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow due to primary radiocapitellar arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:63-69.

33 Minami M, Kato S, Kashiwagi D. Outerbridge-Kashiwagi’s method for arthroplasty of osteoarthritis of the elbow. 44 elbows followed for 8–16 years. J Orthop Sci. 1996;1:1-11.

34 Phillips NJ, Ali A, Stanley D. Treatment of primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. Along term follow up. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2003;85:347-350.

35 Antuna SA, Morrey BF, Adams RA, et al. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: Long term outcome and complications. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2002;84:2168-2173.

36 Cohen AP, Redden JF, Stanley D. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow. A comparison of open and arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:701-706.

37 Kosak TK, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Total elbow arthroplasty in primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:837-842.

38 Naqui SZ, Rajpura A, Nuttall D, et al. Early results of the Acclaim total elbow replacement in patients with primary osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2010;92:668-671.

39 Espag MP, Back DL, Clark DI, et al. Early results of the Souter-Strathclyde unlinked total elbow arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2003;85:351-353.

40 Savoie FH, Nunley PD, Field LD. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications techniques and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214-219.

41 Verhaar J, Van Mameren H, Brandsma A. Risks of neurovascular injury in elbow arthroscopy: starting anteromedially or anterolaterally? Arthroscopy. 1991;7:287-290.

42 Adams JE, Wolff LH3rd, Merten SM, et al. Osteoarthritis of the elbow: results of arthroscopic osteophyte resection and capsulectomy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:126-131.

43 Forster MC, Clark DI, Lunn PG. Elbow osteoarthritis: prognostic indicators in ulnohumeral debridement – the Outerbridge-Kashiwagi procedure. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10:557-560.

44 Hearnden A, Talwalkar SC, Roy N, et al. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty in the management of the arthritic elbow. Shoulder Elbow. 2009;1:95-98.

45 Wada T, Isogai S, Ishii S, et al. Debridement arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2004;86:233-241.