Chapter 272 Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis

Clinical Manifestations

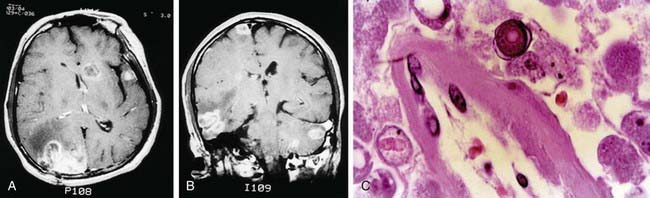

Granulomatous amebic meningoencephalitis may occur weeks to months after infection. The presenting signs and symptoms are often those of single or multiple central nervous system space-occupying lesions and include hemiparesis, personality changes, seizures, and drowsiness. Altered mental status is often a prominent symptom. Headache and fever occur only sporadically, but stiff neck is seen in a majority of cases. Palsies of the cranial nerves may be present. There is also 1 report of acute hydrocephalus and fever with Balamuthia. Results of neuroimaging studies of the brain usually demonstrate multiple low-density lesions resembling infarcts or enhancing lesions of granulomas (Fig. 272-1).

Bennett WM, Nespral JF, Rosson MW, et al. Use of organs for transplantation from a donor with primary meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1334-1335.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Balamuthia amebic encephalitis—California, 1999–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:768-771.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary amebic meningoencephalitis—Arizona, Florida, and Texas, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:573-577.

Deetz TR, Sawyer MH, Billman G, et al. Successful treatment of Balamuthia amoebic encephalitis: presentation of 2 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1304-1312.

Gelman BB, Popov V, Chaljub G, et al. Neuropathological and ultrastructural features of amebic encephalitis caused by Sappinia diploidea. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:990-998.

Radford CF, Minassian DC, Dart J. Acanthamoeba keratitis in England and Wales: incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:536-542.

Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Opportunistic amoebae: challenges in prophylaxis and treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7:41-51.

Schuster FL, Visvesvara GS. Free-living amoebae as opportunistic and non-opportunistic pathogens of humans and animals. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1001-1027.

Vargas-Zepeda J, Gomez-Alcala AV, Vasquez-Morales JA, et al. Successful treatment of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis by using intravenous amphotericin B, fluconazole and rifampicin. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:83-86.