Importance and incidence of locomotor system dysfunctions 363

8.2 Principles and goals of prevention 364

8.4 Manipulation as a prophylactic measure 369

8.1. Importance and incidence of locomotor system dysfunctions

The previous chapter in particular has highlighted the role of dysfunctions of the spinal column in the pathogenesis of pain involving the locomotor system. That discussion will enable us now to formulate a strategy for their prevention as we remind ourselves that it is possible to apply preventive principles not only to therapy itself, but also to rehabilitation, the main goal of which is to ward off relapses and complications.

Before going into detail, we first need to consider the importance of locomotor system dysfunctions and the sheer scale of the problems they pose. The patients we see comprise the vast majority of all those who suffer from back pain and from pain associated in any way with the spinal column. The statistical data are unreliable because our patients are recorded under a range of different diagnostic labels, for example headache, chest pain, vertigo, rheumatism, etc. Many patients who suffer constantly from these painful conditions do not even seek medical help, having learned from experience that conventional treatment is ineffective: and so they escape the record. Even so, the statistics are impressive.

The category heading of ‘soft-tissue rheumatism’ clearly includes many patients suffering from locomotor system dysfunctions. As a cause of absenteeism from work, it is a sobering fact that locomotor system disorders rank second only behind common infections of the upper respiratory tract. However, if we consider only those locomotor system disorders that are of vertebrogenic origin, we find that they account for 15 million lost working days.

Table 8.1 gives official data from the Czech Republic. These give a good overview and are significant economically; they cover only patients who missed work because of their symptoms.

| *Since 1989 ‘vertebrogenic disease’ has no longer been categorized separately in the statistics issued by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic. |

||||||

| Disease category | Year | Average number of working days lost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | 1979 | 1989 | 2004 | 1989 | 2004 | |

| Locomotor system disease | 7898 | 9451 | 11798 | 11627 | 21.9 | 53.0 |

| Vertebrogenic disease | 3763 | 4895 | 7338 | 19.9 | * | |

| Circulatory disease | 3114 | 3335 | 2254 | 35.7 | 69.4 | |

| Psychiatric disease | 1430 | 1229 | 1075 | 32.0 | 68.9 | |

| Neurological disease | 1037 | 940 | 732 | 29.0 | 64.0 | |

| Respiratory infection | 36538 | 40203 | 37896 | 9.4 | 17.6 | |

Impressive though this statistic may be, unfitness for work is only part of the problem. It is mainly low-back pain and/or pain in the lower extremities that renders people unfit for work, and ‘unfitness’ also depends on the nature of the work involved. It is therefore critical to cite data that relate more directly to the incidence of locomotor system dysfunctions. According to Säker (1957), in a survey population aged between 60 and 80 years, 440 out of 1000 people questioned stated that they had experienced at least one episode of low-back pain or sciatica in their lives. In his 1951 study conducted in Stockholm among 1200 workers from a variety of occupations, Hult (1954) found current symptoms or a history of cervical disk or lumbar disk lesions in 51% and 60% respectively. In a randomly selected rural district near Prague, Uttl (1966) found that 61 subjects from a representative sample of 100 had a history of vertebrogenic symptoms.

When older and more recent data are compared, it is evident that the incidence of such dysfunctions is increasing year on year and that the number of lost working days has in fact doubled over the course of 20 years. Locomotor system dysfunctions primarily affect middle-aged individuals, that is those in the most productive years of their working lives. Treatment is frequently time-consuming and costly, and there is a marked tendency for these conditions to become chronic. The cardinal symptom is pain, and this is associated with a burden of suffering that is impossible to quantify. According to Frymoyer (1991, Frymoyer et al 1980), back pain affects 80% of the general population at some point in their lifetime.

8.2. Principles and goals of prevention

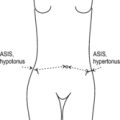

As locomotor system dysfunctions play a key role in the pathogenesis of back pain, it is important to know the circumstances that most frequently produce them. Major factors here also include muscle imbalance, instability, and faulty patterns of muscle movement, among which incorrect breathing is probably the most common.

No less important is the influence of the modern industrialized world in which we live: not only have our dietary habits altered, but we are also exposed to air and water pollution and to risks from chemicals and radiation. And the change in our locomotor habits has been no less radical: although we have become increasingly sedentary, excessive static strain is on the increase. It is precisely this that produces the imbalances described by Janda: our predominantly postural, phylogenetically ‘older’ muscles become hyperactive and contract, whereas our predominantly phasic, phylogenetically ‘younger’ muscles grow flaccid. The same process is also at work in the deep stabilizers. This is one reason for the epidemic increase in disorders involving the locomotor system and spinal column.

Instead of walking, or even riding, we sit or stand in automobiles and other vehicles in which we are jolted about. Most work nowadays is carried out in a more or less fixed position, frequently sitting or bending forward. Long hours of working at the computer are especially harmful. And the worst thing about this unfavorable trend is that it begins in early childhood: in front of the TV screen, sitting in school, or playing computer games. Children travel to school by automobile, bus, or tramcar, even though the distance may be short. Healthy children may resist this trend for a while, boisterously involving themselves in fun and games, but once they start to grow older they are seduced by the appeal of watching TV, riding motorbikes or sitting in a café or bar. These facts deserve to be emphasized because the public gaze is so narrowly focused on environmental pollution that the harm done as a result of changes to our patterns of locomotor behavior is easily overlooked. From this there emerge two logical approaches to prevention: one is to minimize excessive static strain as far as possible, and the other is to seek to compensate for it by exercise.

Our highly-developed technological society is suffering from the twin evils of sedentary lifestyle and excessive static strain.

8.3. Lifestyle factors

8.3.1. Passive prevention

Sitting

As most of our time is spent seated, a correct sitting position is of great importance. This, however, depends on the chair used: the height of the chair is correct if the subject’s thighs are horizontal, with feet resting flat on the floor. The back of the chair should provide support where the kyphosis peaks in a position of complete relaxation (see Figure 6.159). When the patient is sitting relaxed, the peak of kyphosis is more often in the lumbar than in the thoracic region of the back. Under these circumstances it may even be helpful if the sitting surface is tilted backward slightly. If leaning back is not possible, then the patient’s elbows and forearms should be able to rest on the desk or work surface.

If the patient is not supported either by the chair back or the desk/work table, it is better if the seat slopes up at the back, rather like a saddle, because this tilts the pelvis forward and prevents excessive lumbar kyphosis. Special chairs are now manufactured with the seat tilted forward and a knee rest, thus ensuring that the patient sits up straight. However, it is helpful to advise the patient to change sitting position as soon as back pain is felt, and chairs should be recommended that allow patients to vary their position. Specially-designed wedged cushions are also recommended. Long periods of sitting can be particularly harmful if they are compounded by jolting, for example when riding on lorries or tractors (the shock absorption and suspension on such vehicles should therefore be as smooth and efficient as possible).

It is important that the height of the desk or work table is on a level with the elbows when the patient is sitting upright with upper arms vertical. If the chair has forearm rests, these should be adjusted to the height of the freely hanging elbows. For work at the computer, it is also important that the monitor is positioned so that the patient’s gaze is not directed up or down or to one side.

Like forward-bending of the trunk, head and neck anteflexion can also pose problems in the long term. Care must therefore be taken to ensure that this head position is avoided if at all possible. If the work surface is horizontal, the plane of the visual field forces the head into anteflexion. This can be overcome by using a desk with a tilted surface but not by raising the height of the desk. A potentially even more harmful situation arises when simple head and neck anteflexion is compounded by rotation of the head to one side. This is the position typically adopted by keyboard operators as they copy texts lying flat on the desk. The remedy is for the text to be positioned directly in front of the keyboard operator.

Standing

If work is performed standing, the goal should be an erect posture, because a forward-bending position held for any length of time is always a strain. At this point it is helpful to note that bending forward slightly, for example over a wash basin while shaving, may constitute more of a strain than maximum forward-bending. This is because in the former position the erector spinae is maximally contracted, exerting greatest pressure on the spinal column (see Cyriax’s ‘painful arc’, Section 4.6.1). During forward-bending, it is therefore always recommended to advance one leg while bending the knee at the same time (see Figure 4.72). When standing at the wash basin, patients should turn to the side slightly and brace themselves with one thigh against the basin.

Lifting and carrying

If lifting is the cause of symptoms (or relapses), the patient must be taught how to lift objects correctly. For light objects, the principle is the same as when bending forward: there must be harmonious synergism between the trunk and the advanced leg, and ‘uncurling’ of the trunk is accompanied by co-contraction of the abdominal muscles. Heavy objects should be lifted with a straight back while bending and straightening the knees and holding the load close to the trunk to eliminate any leverage effect. Here, too, it would be ideal if everyone obliged to work bending forward for long periods were encouraged to change this position occasionally, or given a short break in which to do so.

Sleeping position

Just as important as the position held during the day is the way the body lies at night, in bed. It is no exaggeration to say that there are few lifestyle factors that affect the spinal column so powerfully – for good or ill – as the patient’s sleeping position in bed. This applies especially in cases where a patient reports that symptoms are felt mainly during the night or in the morning on waking up. Questioning about the type of bed slept on is usually followed by advice to use a hard mattress over a firm, unyielding frame. We believe that this is the wrong approach. The patient should first demonstrate the usual sleeping position and only then should we offer advice on how this might be corrected. For this we need to know, for example, whether the patient’s symptoms are mainly in the cervical or lumbosacral region.

If symptoms are mainly in the low back we need to know whether the patient sleeps in the supine, side-lying, or prone position. If the answer is supine or prone, and symptoms occur during the night or on waking, the trouble is usually due to lordosis. We may then advise the patient either to adopt a side-lying position, or – if the patient lies supine – to put a thick pillow under the legs or a rolled towel or blanket under the waist. If the patient sleeps in the prone position, it is usually best to advise a different position. If that proves impossible, it can be helpful to raise the pelvis using a pillow. If side-lying produces symptoms, this may be due to scoliosis because the shoulders and pelvis are wider than the waist. In this case a rolled towel should be placed under the waist.

More often though it is necessary to correct the patient’s sleeping position due to symptoms associated with the cervical spine. This is also borne out by the fact that acute wry neck and cervicogenic headache most frequently occur after a night in bed, and radicular pain has a tendency to be worse when lying down. All too frequently advice is given to patients to lie flat. This counsel may be helpful for a young person who sleeps in the supine position. However, if the patient sleeps side-lying, it should be remembered that the shoulders are wider than the head. If such a patient sleeps with only a thin pillow (or no pillow at all), this means that the cervical spine slopes downward at an angle. The patient’s head should be supported so as to keep the cervical spine in a neutral position; this will depend not only on the width of the shoulders but also on the position that the patient adopts. Many patients demonstrate a side-lying position in which one arm is under their head. While they cannot sustain this position for long, they are nevertheless demonstrating their need for a sufficiently thick support. The pillow should be squarish, sufficiently big so that the patient’s head does not slip off it, and firm enough to give constant support. It must not be placed under the shoulders and therefore should not be wedge-shaped.

If the patient has the unfortunate habit of lying prone, this should be discouraged, because it is a position that forces the cervical spine into maximum rotation. Again, a firm pillow giving the necessary support to allow comfortable side-lying will both encourage this and prove an obstacle if the patient tries to turn into a prone position. Specially-designed pillows with a hole for the face and nose can be purchased that enable the patient to lie prone with the head in a neutral position. However, this position may produce extreme cervical lordosis. The most suitable compromise for those who cannot drop this habit is to place a large pillow under the shoulder and chest on the side to which the head is turned, instructing them to clutch this to them, thus lessening neck rotation. The habit of lying prone usually dates from early childhood, when the position has much to recommend it; later in life, unfortunately, it can give rise to pathological changes.

Even when lying supine, most older people with a rounded back need a fairly thick, firm head support to prevent their head falling into retroflexion. Head retroflexion is not only unfavorable for the cervical spine but may actually jeopardize the blood supply to the vertebrobasilar region, especially if there are already signs of arteriosclerosis.

Summary

In each individual case it is most important to identify the circumstances that precipitate symptoms, so as to prevent further disturbances or relapses. In fact, there is probably no more effective way of helping these patients than by judicious advice concerning workplace organization, leisure activities, and sleeping position.

Our best treatment efforts often go awry because we fail to discover that the patient adopts a faulty position when working at the computer, or sits incorrectly when driving, or stands without proper support. It is therefore a grave omission on our part if, after learning that symptoms occur in the morning, we do not ask for a demonstration of the patient’s usual sleeping position – or if we learn that symptoms are precipitated by lifting or carrying objects and fail to investigate the patient’s techniques for doing this. Indeed, one of the main purposes of taking the case history is to investigate these matters meticulously. We are of no help to the patient in the long term if we detect a lifestyle error on repeated visits and fail to offer advice as to how this might be corrected. It also follows that prevention of disease or relapse and advice on lifestyle-related issues apply equally to patients and to the healthy population.

8.3.2. Active prevention

There are a number of activities – especially leisure pursuits – that can be used to compensate for the potentially harmful effects of the technological society in which we live.

Sports

The amount of exercise taken can be easily increased by making minor changes to our habitual lifestyle: for example, people might walk to work or use the stairs instead of taking the elevator.

Patients often ask which activities or sports they should take up for prophylactic reasons. The question seems straightforward, but we are instantly aware that there is no simple answer. Not only do the various forms of sport and physical exercise affect our bodies in very different ways, but they may even be downright harmful. It is therefore essential to analyze each type of sport carefully, bearing in mind the patient’s constitution and their medical history. Then there is the question of competitive sports: in view of the extreme and ever-increasing demands made by competitive sports on their devotees, their usefulness for prevention of disease is highly questionable. Indeed, competitive athletes are among the groups who are most at risk and most likely to become our future patients.

It cannot fall within the scope of this book to give a comprehensive picture of the effect of various types of sport on the locomotor system. It may be useful, however, to give a few examples of how to approach the question. Take swimming, for example, considered by most people to be a particularly ‘healthy’ sport: all the muscles are brought into play, the body weight does not act on the spinal column and there is very little risk of injury. On further analysis, however, we find that the breast stroke and even the crawl make the pectoralis muscles overactive and taut, so that most swimmers become slightly round-shouldered. Moreover, most exponents of the breast stroke and the ‘butterfly’ tend to develop lumbar hyperlordosis and hypermobility. Elderly swimmers have a habit of holding their head out of the water while swimming, keeping the cervical spine in hyperlordosis. All of which is not intended to imply that swimming is harmful. Patients who are round-shouldered or who have lumbar hyperlordosis should be advised to swim on their back if they suffer from low-back pain. And because swimming in cold water sends a signal to the body to form a good layer of insulation, this particular type of swimming is not recommended for people wishing to lose weight.

Volleyball is one of the most popular and at the same time one of the most dangerous types of sport. As they leap up and land again on the ground, players at the net must keep their lumbar spine in hyperlordosis so that no part of their body touches the net. This is most unphysiological and constitutes a great danger to the low lumbar disks (‘nutcracker mechanism’). High-board diving poses dangers for the same reason, with spondylolisthesis being significantly more frequent among divers than in the population at large (Groh 1972).

As usually taught, gymnastic exercises have a tendency to aggravate muscle imbalance, particularly when the legs and trunk are held straight and at right angles to each other. In order to achieve this, the gymnast is required to suppress the normal function of the abdominal muscles, which is to approximate the xiphoid process of the sternum to the pubic symphysis and thus bring the lumbar spine into kyphosis. Instead, the iliopsoas and the erector spinae enable the gymnast to hold the legs straight at right angles to the trunk, the net result of such training being to provoke what Janda defined as the ‘lower crossed syndrome’ (see Section 4.16). An important protective mechanism is lost, namely that of curling and uncurling the lumbar spine, to be replaced by unphysiological leverage in the particularly vulnerable lumbosacral region. In terms of prevention, therefore, preference should always be given to exercises that have become familiar to us from yoga or Tai Chi. In these traditional exercise systems, movements are smooth, never abrupt, while at the same time being rounded and gradual. Muscle contraction and relaxation are alternated and there is a focus on correct breathing; all these aspects tend to be absent from European-style gymnastics.

Apparatus-based gymnastic exercises routinely make the upper fixators of the shoulder girdle overactive, leading to the ‘upper crossed syndrome’ (see Section 4.16). The emphasis on very rapid, forceful movement here makes safe control of the body difficult, and it is not easy to avoid (micro-)trauma.

One leisure activity that can always be recommended is regular walking, preferably on soft paths and wearing suitable trainers that support and cushion the feet; this is the most physiological form of locomotor movement. Similarly, cross-country skiing has much to commend it because it also exercises the arms, as does Nordic walking. We should also not forget that dancing is among the oldest forms of exercise that people have enjoyed throughout history. Because it can be carried on for hours at a time, its beneficial effects are considerable while harmful effects are a rare exception. Dancing can also be highly recommended as a weapon in the war against obesity. However, with the high noise levels generated by modern amplification systems, a warning against auditory damage may not be out of place.

Clothing

Although posture and movement, and their correction, naturally play the principal part in preventing disturbed locomotor function and its sequelae, the influence of other important factors such as food and clothing should not be underestimated.

It has long been known that regions that are highly susceptible to pain, such as the neck and low back, should be protected from cold and draughts, especially in situations where the individual is perspiring. (In this regard, many aspects of modern-day women’s fashion are particularly harmful.) At the same time it is also necessary to develop a certain degree of resistance or hardening. Thus although it is sensible to protect regions that we know are apt to be vulnerable to symptoms, we should aim to harden the body as a whole. Nor should it be forgotten that the susceptibility to cold of certain body regions is often due to a clinically latent lesion that is localized there, and that after successful treatment cautious hardening may be undertaken. Nevertheless, the main purpose of wearing clothes is to protect the body from the cold, but this should be judicious so as to maintain thermoregulation and the ability to cope with fluctuations in temperature. Besides clothing, this also applies to the question of when and to what extent we should expose our bodies to the air, water, and the sun.

There is yet another side to the question, something that might be termed the mechanical effect of clothing; and the most telling example here is the sometimes devastating effect of brassieres that are too tight. Tight brassieres with thin straps cut deeply into the skin and muscles of the shoulders, resulting in permanent excessive strain in which the shoulder girdle and cervical spine are drawn forward. Overlooking this problem in our female patients may be the root cause of treatment failure. Use of shopping bags instead of rucksacks can also be harmful. For men, wearing belts that are too tight can be a problem, particularly in cases where there are hyperalgesic zones in the abdominal or dorsal regions. Braces are recommended for obese patients. Wearing pantyhose is not helpful for women with weak abdominal muscles; elasticated stocking suspenders are far better if an abdominal support belt around the waist is not necessary.

Without doubt, shoes are the biggest problem area. High heels do not merely change the position of the feet but also tilt the pelvis forward, thus altering the body’s center of gravity, as well as accentuating lumbar lordosis, which in turn adversely affects the abdominal muscles and breathing. What is more, the toes are forced into dorsiflexion and the great toe is angled away from the midline of the body, which encourages the development of splay foot and hallux valgus. From the purely physiological standpoint, only walking barefoot can be termed ‘normal’; footwear should therefore be constructed from yielding material that allows the foot to adapt well to the walking surface. Hard soles and heels should therefore be avoided, and they are especially harmful where osteoarthritis is already present in the joints of the lower extremities.

Obesity

It is only too obvious that the campaign against obesity common to many fields of medicine is very relevant for the correct functioning of the locomotor system. A vicious circle easily develops in which pain (due to overstrain and faulty statics) makes the patient reluctant to move and lack of movement encourages obesity.

It is beyond the scope of this book to deal in detail with the problem of obesity. However, it is important to decide whether obesity is a relevant factor in any given case. We should remember that obesity seriously affects the joints of the lower extremities in particular, less so the lumbosacral spine, and at most has only indirect relevance for the cervical spine. We frequently encounter subjects who have very little fat on their trunk but whose buttocks and thighs are hugely obese; this may be completely irrelevant for the spinal column.

The patient’s somatic type is also important: individuals with a stocky, compact (‘pyknic’) build tolerate obesity much better than those with a graceful (‘asthenic’) build. A stockily-built subject who weighed about 80kg at 20 years, increasing to 90 or even 100kg at 50 years, may handle the additional weight very well, whereas someone who weighed 50 or 60kg at 20 years, increasing to 80 or 90kg at 50 years, will be decompensated. When advising weight reduction we must have good reason to think that obesity is a potential cause of the symptoms.

8.4. Manipulation as a prophylactic measure

Having discussed some of the basic principles of prevention, we will now turn to the question of preventive correction of specific disturbances.

Treatment should not be directed only at the site where pain is manifest. Instead we should attempt to target treatment at those structures that appear to be key regions for the dysfunction in question, even though the patient may be experiencing no pain there whatsoever, because we are convinced that abnormal findings in these structures are a source of potential trouble. We do this because the pain for which the patient is seeking help would shortly recur if we were not to take such action. From this it is evident that the aspect of prevention must also be taken into account when we are establishing the indications for treatment. We should therefore ask ourselves whether, and under what circumstances, it is justifiable to treat clinically latent lesions in persons without (perceived) symptoms, purely for reasons of prevention. This needs to be considered particularly in cases of non-painful restriction in a motion segment or of latent trigger points (TrPs) that can be easily abolished.

So what are the options for treating patients with non-painful dysfunctions, purely as a prophylactic measure? Given the astronomical incidence of latent dysfunctions, prophylactic manipulative treatment for the population as a whole is probably an illusory goal. However, it may be entirely reasonable in future to envisage such preventive measures for pre-school and school children. Our own experience suggests that a locomotor system check-up once a year would be sufficient, to be carried out exclusively by qualified physicians and/or physiotherapists. This would ensure prevention during the decisive growth phase.

There are also a number of at-risk groups for whom preventive manipulation is indeed desirable. The first category comprises patients recovering from injury, and this group may be further extended to include those recovering from painful visceral diseases where spinal column involvement is to be anticipated. Surgical patients are another candidate group here because the position of the head for intubation is likely to result in dysfunctions involving the cervical spine. Similar considerations are appropriate following tonsillectomy. There may also be some value in advocating preventive manipulation for certain occupational groups that appear to be at particular risk, although, as we have noted, this might be seen as including most occupations in our modern technological society. However, there is one group in which manipulative treatment for preventive purposes is justified, namely competitive athletes, a fact which throws light on the effects of competitive sport. One other aspect should be mentioned while we are on the subject of prevention: it is imperative that choice of employment should take into account the individual’s physical constitution. And here we are most concerned with hypermobility; it is the hypermobile subject who is least able to tolerate static overstrain and jolting.

It would of course be misleading to give the impression that manipulation is the only therapeutic measure with a potential role in prevention. It forms the subject of this book, and serves to illustrate the fact that a therapeutic method can also be useful for prevention. The classic method used in a preventive setting is, of course, remedial exercise, and this has been accorded due importance in 4 and 6. Remedial exercise, too, is effective only if it is applied specifically on the basis of a precise diagnosis. However, it must be emphasized that remedial exercise is far more demanding in terms of time and effort than are manipulation or TrP treatment. Herein perhaps lies the chief reason for its limited practicability in a preventive context.

Remedial exercise has always been used for children with bad posture, but it has only ever been implemented consistently in a tiny proportion of those who need it. A more effective approach would be to introduce the principles of remedial exercise into normal physical education in schools: teaching correct techniques for respiration, bending down, picking up objects from the floor, carrying bags/satchels, and sitting. I have already made reference to the potentially harmful effects of traditional European-style exercise systems, but it would certainly also be possible to introduce many elements from yoga into school gymnastics lessons. However, the greatest obstacle to achieving this is the attitude of many, if not most, physical training instructors. Like sports trainers, they are primarily interested in those children who shine in sports and gymnastics – those who (perhaps to their own detriment) seem promising as future competitive athletes. Instead it is the ‘awkward’ children who really need more of the teacher’s attention. In sports and athletics clubs, the above attitude is even more accentuated: in the public interest, youngsters deemed not to have what it takes to make the grade at the very highest level are ruthlessly dropped from the program.

Finally, there are two groups for whom the prescription of remedial exercise is obligatory: these are women after childbirth and, for the same reason, patients with weak abdominal muscles after abdominal surgery. Failure to prescribe remedial exercise in such cases constitutes gross negligence.