CHAPTER 40 Presigmoid Keyhole Approach for Petroclival Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas are one of the most commonly seen lesions of the petroclival and clival regions. Approaches to the cerebellopontine angle, the petroclival region, and the ventral aspect of the brain are technically challenging in neurosurgery. Initially these tumors were thought to be “inoperable,” as surgical attempts to remove them were associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality in the early series. More recently, skull-base surgery has undergone a remarkable evolution with resulting progress in radiodiagnostic techniques, intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring, and better investigation of the microsurgical anatomy of this region. As a result, surgical management of these tumors has been evolving, leading to better outcome and a marked reduction in surgical morbidity and mortality.1–9 However, radical excision of these tumors via all the modern skull-base surgery techniques is discouraging even in the hands of experienced cranial base surgeons.1,4,10 Moreover, many surgeons changed their philosophy of treatment approach from radical to conservative because of the good results achieved with adjuvant radiosurgery and probably also because complex surgery may have a paramount impact on the patients’ health.1,4,10

THE ADVENTURE THROUGH THE OPTIMAL APPROACH

The term “petroclival meningioma” was defined as meningiomas having their point of origin at the upper ⅔ of the clivus and petrous apex, medial to the trigeminal nerve. Extension to the medial tentorium, Meckel’s cave, middle cranial fossa, parasellar area, petrosal and cavernous sinuses, and cranial nerve (CN) foramina may be seen. Traditionally, major routes used to reach these areas are the middle cranial fossa (subtemporal),2,11–15 transpetrosal,1,9,16,17 suboccipital retrosigmoid,18–22 and combined approaches.23–26 Each method has its advocates, and comparable results have been reported in the literature.

The so-called subtemporal approach was originally adapted by Drake for elimination of basilar aneurysms and modified later by many authors.12,15,27 It is possible to reach the upper clival, tentorial notch, and petrous apex region by this method. For petroclival meningiomas, approach through the middle fossa is a fascinating proposition because it affords immediate visibility and complete control of the supratentorial tumor bulge. In our experience, however, it is also a highly hazardous route. Retraction of the temporal lobe can cause some heavy postoperative morbidity, especially on the dominant side. Access to the posterior fossa also remains narrow and tedious, affording insufficient command of CNs below the trigeminal nerve. Because of this subtotal excision is more possible with this approach, especially if the tumor is reaching downward through the lower clivus.

The classical retrosigmoid approach,18–22 with unroofing of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses to keep them out of the surgical field and moderate, readily tolerated, cerebellar retraction affords the simplest access to the region of the cerebellopontine angle and lateral clivus. However, it is difficult to resect tumors that are implanted all the way to the dura of the cavernous sinus and sella turcica and those that involve Meckel’s cave and tentorium to encase CN III and/or the internal carotid artery. In addition, the retrosigmoid approach does not provide a direct view of the brain stem–tumor interface. Another drawback may be found in the fact that the surgeon must conduct the whole phase of removal through the fissures made by the tentorium and by CNs V, VII–VIII, and IX–XI, all of which may be contused in the process.

HISTORY OF THE TRANSPETROSAL APPROACH

A combined supra–infratentorial presigmoid transpetrosal approach without sigmoid sinus division embodies some important refinements of the original approach developed by Hakuba and his associates. Hakuba and co-workers28 first described in the neurosurgical literature the surgical technique and results of the transpetrosal transtentorial route, used in eight patients with a retrochiasmatic craniopharyngioma. Again, in 1988 Hakuba16 described his experience using the transpetrosal approach for surgery of clivus meningeomas. In the same year, Al-Mefty and co-workers9 and Samii and Ammirati29 independently described their experience with the technique and results of the transpetrosal approach. Al-Mefty reported on 13 patients with a petroclival meningioma treated using what he called the “petrosal” approach. He described the petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas in which the retrolabyrinthine transtentorial approach was used to preserve hearing. They approached lesions through the petrosal corridor by making a craniotomy of temporo-occipital bone above the tentorium and suboccipital bone below the tentorium, centered on the posterior petrous ridge. Samii29 described nine patients treated with a “combined supra–infratentorial pre-sigmoid sinus avenue” approach. Further reports on the use of the presigmoid transpetrosal approach to tumors of the clivus with some technical modifications came from Sekhar30,31 and Fukushima17 based on their extensive experience in skull-base surgery. Kawase and co-workers32 described the anterior transpetrosal–transtentorial approach to aneurysms of the lower basilar artery. This anterior petrosal approach was later used to remove petroclival tumors.33,34 Like the retrolabyrinthine posterior petrosal approach, the anterior petrosal approach preserves hearing and facial nevre function, even though the exposure is limited. According to the amount of petrous bone drilling there are three variations of the transpetrosal approach: (1) the retrolabyrinthine approach with preservation of hearing, (2) the translabyrinthine technique with more extensive resection of the petrous bone and sacrifice of hearing, and (3) the transcochlear approach with radical petrous bone removal, sacrifice of hearing, and rerouting of the facial nerve.35,36

KEYHOLE APPROACH AND SMALL OPENING OF THE BONE

A combined supra–infratentorial presigmoid transpetrosal approach is well described in the literature.1,9,16,17,28 For this approach, the patient is placed under general endotracheal anesthesia and positioned supine with the head rotated to the side opposite the lesion and fixed in a three-pin head frame (Fig. 40-1). The vertex is lowered as much as possible to allow a good view of the lesion without having to retract the temporal lobe. A small, reverse, hook-shaped supraretroauricular incision is made beginning above the ear and finishing 1 cm distal to the mastoid process (see Fig. 40-1). After the skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised, they are separated in one layer from the muscle layer. The muscles and periosteum are incised in the same fashion and dissected to expose the underlying bone.

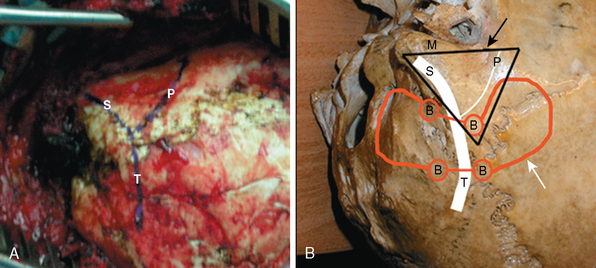

A combined supra–infratentorial craniotomy is a part of transpetrosal approach described by several authors.9,16,17,28 Burr holes are made on each side of the transverse sinus and the temporal bone and then a portion of the occipital bone above and as well as below the tentorium are cut between burr holes with craniotome. As a result a craniotomy flap is raised. A triangular bony area in the petrosal bone in front of this exposed surface is then left. The tumor to be approached is located under this presigmoidal triangle and can be approached upon opening of the dura. What the surgeon actually needs is this space (Fig. 40-2).

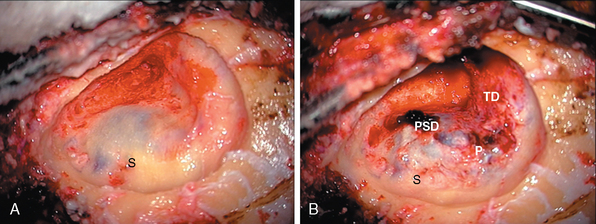

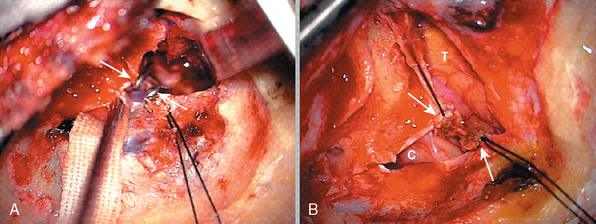

Thus in recent cases we used a different technique called the presigmoid keyhole approach in which we did not perform a craniotomy, in contrast with the preceding discussion.37 For this keyhole presigmoid transpetrosal approach, after the incision and dissection of the skin, muscle, and periosteum and exposing the petrosal bone, a posterior petrosectomy is performed without a preceding craniotomy (Fig. 40-3A). The petrosectomy stage of the presigmoid keyhole approach is identical to that of the conventional combined approach, only with the execption that it is not performed after craniotomy as in the combined approach.

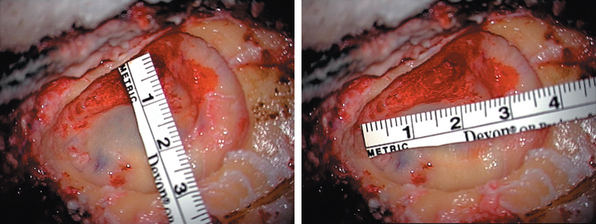

A posterior petrosectomy starts with a mastoidectomy with the use of a high-speed drill. The sigmoid sinus is completely unroofed under the surgical microscope. A suction-irrigator should be used for temporal bone procedures to keep the field free of bone dust and the underlying structures cool. A thin shell of bone can be left on the sigmoid and can later be elevated with a free elevator (Fig. 40-3B). For the posterior petrosectomy, this is followed by a drilling of bone with a sufficient exposure of the presigmoid dura from the superior petrosal sinus to the level of the jugular bulb, while preserving the integrity of the facial canal as well as middle and inner ear structures38 (Fig. 40-4). Petrosectomy should be wide, fully defining the sigmoid and transverse sinuses; it is also important to fully delineate the sinodural angle, the angle defined by the sigmoid sinus with the middle and presigmoid posterior fossa.

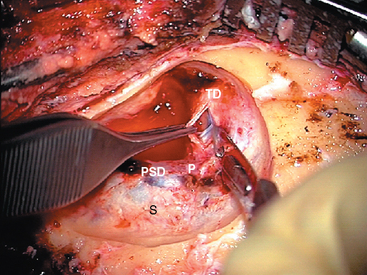

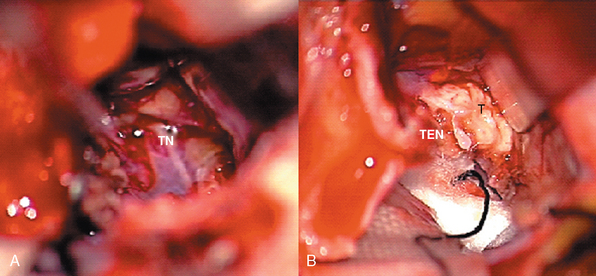

After completion of the extradural bone removal, the temporal dura is incised parallel to the floor of the temporal fossa in the anterior portion of vein of Labbé (Fig. 40-5). The presigmoid dura covering the posterior fossa is then incised up to the superior petrosal sinus, which is coagulated or obliterated using small hemoclips and severed (Fig. 40-6). CSF is released from the cerebellopontine angle cistern. The temporal lobe is slightly elevated and the tentorium is transected completely, parallel to the petrous bone, in the direction of the trochlear nerve (Fig. 40-7). Preservation of the Vein of Labbé during elevation of the temporal lobe and during cutting of the tentorium is very important. After the tentorium has been cut completely, the transverse and sigmoid sinuses and the remaining part of the tentorium can be retracted with self-retaining retractors. The ambient cistern and crus cerebri are then exposed.

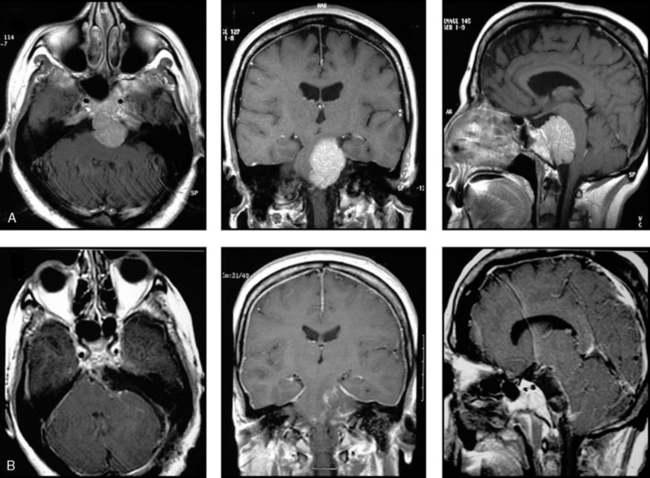

After tumor removal, the dura is closed with a fascial graft. The mastoid bony defect is then packed with a fat graft, Gelfoam, and thrombin/fibrinogen sealant to prevent CSF leakage. Primary closure of the muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin is performed. The cosmetic result is fair (Fig. 40-8A) and the postoperative bony defect is small (Fig. 40-8B).

In our view, in approaching to these tumors, further craniotomy or craniectomy besides the drilled bone is an unnecessary procedure that can potentiate unwanted postoperative complications, as ideal exposure could be achieved and the tumor itself is accessible during the resection (Fig. 40-9). In our experience, the reasons for failure to resect totally were not due to a small opening of bone but the fibrous nature of the tumor, adherence to brain stem, perforating artery and/or cranial nerve encasement, cavernous sinus invasion, and bradycardia during resection.

[1] Seifert V., Raabe A., Zimmermann M. Conservative (labyrinth-preserving) transpetrosal approach to the clivus and petroclival region: indications, complications, results and lessons learned. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145(8):631-642. discussion 642

[2] Goel A. Extended lateral subtemporal approach for petroclival meningiomas: report of experience with 24 cases. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13(3):270-275.

[3] Sekhar L.N., Wright D.C., Richardson R., Monacci W. Petroclival and foramen magnum meningiomas: surgical approaches and pitfalls. J Neurooncol. 1996;29(3):249-259.

[4] Natarajan S.K., Sekhar L.N., Schessel D., Morita A. Petroclival meningiomas: multimodality treatment and outcomes at long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(6):965-979. discussion 979–81

[5] Samii M., Tatagiba M. Experience with 36 surgical cases of petroclival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;118(1–2):27-32.

[6] Zentner J., Meyer B., Vieweg U., et al. Petroclival meningiomas: is radical resection always the best option? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(4):341-345.

[7] Couldwell W.T., Fukushima T., Giannotta S.L., Weiss M.H. Petroclival meningiomas: surgical experience in 109 cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;84(1):20-28.

[8] Bricolo A.P., Turazzi S., Talacchi A., Cristofori L. Microsurgical removal of petroclival meningiomas: a report of 33 patients. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(5):813-828. discussion 828

[9] Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L., Smith R.R. Petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22(3):510-517.

[10] Little K.M., Friedman A.H., Sampson J.H., et al. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: defining resection goals based on risk of neurological morbidity and tumor recurrence rates in 137 patients. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(3):546-559. discussion 546–59

[11] Bonnal J., Louis R., Combalbert A. The transtentorial temporal approach to the cerebellopontile angle and the clivus. Neurochirurgie. 1964;10:3-12.

[12] Rosomoff H.L. The subtemporal transtentorial approach to the cerebellopontine angle. Laryngoscope. 1971;81(9):1448-1454.

[13] Malis L. Suboccipital subtemporal approach to petroclival tumors. In: Wilson C.B., editor. Neurosurgical Procedures: Personal Approaches to Classic Operations. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1992:41-51.

[14] Samii M., Ammirati M., Mahran A., et al. Surgery of petroclival meningiomas: report of 24 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24(1):12-17.

[15] Spetzler R.F. Subtemporal transtentorial approach. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(5):854. author reply 855–6

[16] Hakuba A., Nishimura S., Jang B.J. A combined retroauricular and preauricular transpetrosal-transtentorial approach to clivus meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 1988;30(2):108-116.

[17] Fukushima T. Combined supra-infra-parapetrosal approach for petroclival lesions. In: Sekhar L.N., Janecka I.P., editors. Surgery of Skull Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:661-670.

[18] Markham J.W., Fager C.A., Horrax G., Poppen J.L. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa; their diagnosis, clinical features, and surgical treatment. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1955;74(2):163-170.

[19] Russell J.R., Bucy P.C. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1953;96(2):183-192.

[20] Samii MSekhar L.N. Petroclival and medial tentorial meningiomas. In: Scheunemann H., Scheunemann K., Helms J., editors. Tumors of the Skull Base. Extra- and Intracranial Surgery of Skull Base Tumors. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 1986:141-158.

[21] Goel A., Muzumdar D. Conventional posterior fossa approach for surgery on petroclival meningiomas: a report on an experience with 28 cases. Surg Neurol. 2004;62(4):332-338. discussion 338–40

[22] Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6(1):27-30.

[23] King T.T. Combined translabyrinthine–transtentorial approach to acoustic nerve tumours. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63(8):780-782.

[24] Hitselberger W.E., House W.F. A combined approach to the cerebellopontine angle. A suboccipital-petrosal approach. Arch Otolaryngol. 1966;84(3):267-285.

[25] Blevins N.H., Jackler R.K., Kaplan M.J., Gutin P.H. Combined transpetrosal–subtemporal craniotomy for clival tumors with extension into the posterior fossa. Laryngoscope. 1995;105(9 Pt 1):975-982.

[26] Fujitsu K., Kitsuta Y., Takemoto Y., et al. Combined pre- and retrosigmoid approach for petroclival meningiomas with the aid of a rotatable head frame: peri-auricular three-quarter twist-rotation approach: technical note. Skull Base. 2004;14(4):209-215. discussion 215

[27] Drake C. The surgical treatment of aneurysms of the basilar artery. J Neurosurg. 1968;29:436-446.

[28] Hakuba A., Nishimura S., Inoue Y. Transpetrosal-transtentorial approach and its application in the therapy of retrochiasmatic craniopharyngiomas. Surg Neurol. 1985;24(4):405-415.

[29] Samii M., Ammirati M. The combined supra-infratentorial pre-sigmoid sinus avenue to the petro-clival region. Surgical technique and clinical applications. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;95(1–2):6-12.

[30] Javed T., Sekhar L.N. Surgical management of clival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1991;53:171-182.

[31] Sekhar L.N., Jannetta P.J., Burkhart L.E., Janosky J.E. Meningiomas involving the clivus: a six-year experience with 41 patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;27(5):764-781. discussion 781

[32] Kawase T., Toya S., Shiobara R., Mine T. Transpetrosal approach for aneurysms of the lower basilar artery. J Neurosurg. 1985;63(6):857-861.

[33] House W.F., Hitselberger W.E., Horn K.L. The middle fossa transpetrous approach to the anterior-superior cerebellopontine angle. Am J Otol. 1986;7(1):1-4.

[34] Kawase T., Shiobara R., Toya S. Anterior transpetrosal–transtentorial approach for sphenopetroclival meningiomas: surgical method and results in 10 patients. Neurosurgery. 1991;28(6):869-875. discussion 875–6

[35] Spetzler R.F., Daspit C.P., Pappas C.T. Combined approach for lesions involving the cerebellopontine angle and skull base: experience with 30 cases. Skull Base Surg. 1991;1(4):226-234.

[36] Spetzler R.F., Daspit C.P., Pappas C.T. The combined supra- and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76(4):588-599.

[37] Türe U, Pamir MN. Small petrosal approach to the middle portion of the mediobasal temporal region: technical case report. Surg Neurol 2004;61:60–7.

[38] Ammirati M., Cheatham M.L., Ma J., et al. Drilling the posterior wall of the petrous pyramid: a microneurosurgical anatomical study. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:452-455.