Chapter 1 Preparing for the fellowship examination

The format of the fellowship examination

At all times during the examination you are iden tified only as a number: names are not used. The initial digits indicate the number of the examination and subsequent digits are assigned in a manner so as not to identify candidates in any way. For example, the second examination in 2008 was the 42nd fellowship examination, so candidate numbers ranged from 4201 upwards. For the clinical components, you will be provided with a sticker to wear with your number on it. A marking scale out of 10 is used throughout the examination. A score of five constitutes a pass.

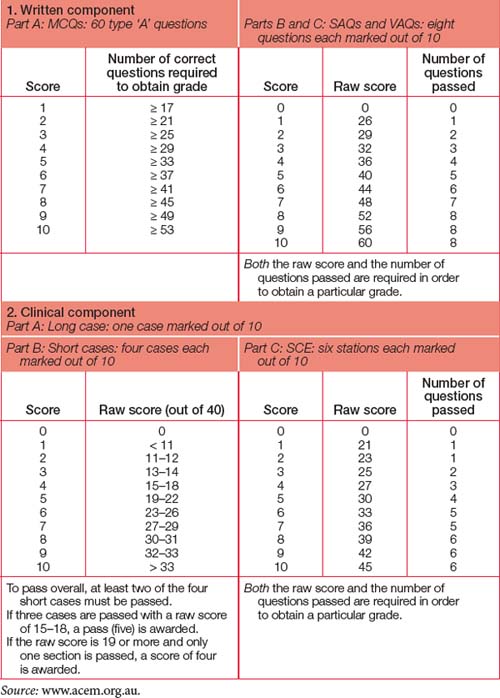

Written component

Clinical component

The three parts of the clinical component are conducted over two days. This is typically held on a Saturday and Sunday in an outpatient/clinic facility, but may vary. Usually the long and short cases are spread over two sites, with candidates and examiners spending the whole day at one site, whereas the structured clinical examination (SCE) is held at a single venue. The current format of the examination has the long case on the first morning, the short cases in the afternoon and the SCE on the second day.

Short cases

Each candidate sees a total of four short cases — two cases with one pair of examiners and another two cases with a different pair of examiners — with the expectation that at least one of these cases will involve a child. Each of the four examiners will act as the lead for an individual case. Twenty minutes is assigned to each pair of cases, which is roughly to be split between the two cases. After the first 20 minutes on two cases, you will be escorted to a different location (often next door or across the corridor). When the bell is rung five minutes later, you have the second 20 minutes with the second pair of cases and examiners. The examiners award a score out of 10 for each individual short case, and these scores are then consolidated to derive an overall score out of 10. To achieve an overall pass, candidates must pass at least two of the four cases. Consistency is rewarded more than good performance on individual cases (see Table 1.1).

Structured clinical examination (SCE)

The final section of the fellowship examination consists of the SCE with six stations. The usual format is like musical chairs in six adjacent rooms (except in this game everyone gets a seat!). Outside each room is a brief ‘prompt’ such as a brief clinical scenario. For each station, you are allocated three minutes to get to the station and review the ‘prompt’, and seven minutes to spend with a pair of examiners, one of whom will act as lead while the other scribes. Candidates should expect that one station will focus on a difficult communication or administration scenario with an actor involved. Each of the six stations is marked out of 10: to achieve an overall pass, candidates must pass at least four stations and attain a total score of 30 or more. Once again, consistency is rewarded more than good performance at individual stations. Five or more stations must be passed to pass the section overall (see Table 1.1).

Notification of results

Once you have completed the final clinical compon ent, stay near the venue if you can, as the examiners meet shortly after candidates complete this component. Following this examiners’ meeting, the list of successful candidates is prepared for posting outside the venue and on the College website, and individual envelopes are prepared containing results. The envelopes are handed out at the designated time, usually approximately two hours after the clinical component has been completed. There is no distinction between the envelopes of ‘successful’ and ‘unsuccessful’ candidates: they all look identical, with only the candidate number on the outside. Those results not collected are mailed out to candidates.

Who are the examiners?

You may occasionally find a scribing third examiner join the active pair. This is a ‘peer support’ examiner. Like the other observers, this person will not examine you and will not interact with you. Select ed from the senior court of examiners, this person is there to provide feedback to the examiners on their per formance as a quality assurance measure. Even the examiners get examined!

The journey to the fellowship examination

Obviously, the best way to become comfortable and familiar with doing things the ‘examination’ way is to do them routinely every day. During departmental teaching sessions, every question is a SCE, SAQ and/or VAQ opportunity. Develop a style for approaching these questions. Every case you see is at least a short case and potentially a long case. The short case examination technique is very time efficient. Develop a technique for each organ ‘system’ and use it on each and every patient you see. If the patient appears to have issues that would be well suited for a long case and is not acutely unwell, limit yourself to 35 minutes, spend five minutes collating your thoughts and then present the case to a colleague. If you have a sufficiently cooperative patient and ‘study buddy’ or colleague, ask your colleague to see the patient first, check the notes and then do it as a true ‘mock’ long case.

Core principles

Which section should you prepare for first?

If you adopt the core principles outlined above, embedding them as part of your everyday practice, you will already be preparing for every section.

Where can you find the best information?

The College website (www.acem.org.au) is a virtual goldmine of information, including the curriculum, examination reports, numerous guidelines, policies, position statements and other material covering every aspect of FACEM activity. The site also has the contact details for the College Secretariat, which will help you navigate the maze if you get lost. Spend a lot of time at this site.

There are a number of recommended texts: use those that work best for you. The reference list in Chapter 9 can give you a starting point, as it highlights what most FACEMs find of greatest value. In addition, the source journals listed in the chapter are those that are most read by FACEMs and so should guide you towards what will be foremost in the minds of your examiners, those who will be setting the questions and those who will be assisting you in your preparation.

Critique

Part of the pathway to success involves getting others to ‘assess’ your performance. Without constructive critique, you cannot correct deficiencies and improve. As you start presenting cases, practising written components and responding to probing questions, you will inevitably receive feedback that leaves you feeling deflated and despondent. There is no way to avoid this, so you need to develop a strategy to deal with it. Keep going — as you progress, this will happen less often. And remember, even your most admired FACEM occasionally gets things wrong and does not know all the answers. If they can handle it, so can you.

Preparation courses/opportunities

A number of formal and informal opportunities exist to participate in activities that will assist you in preparing for the fellowship examination. The ACEM Annual Scientific Meeting (late in the year) and Winter Symposium (mid-year) are excellent opportunities to meet other trainees and FACEMs from all regions. Oral and poster presentations can guide you on how to present and how questions can be addressed, and this can be enormously valuable when considering your own presentation/publication requirement.

ALS (advanced life support) course

A variety of course formats exist, with courses run regularly throughout Australasia. Courses approved by the Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC) can be accessed via its website (www.resus.org.au).

APLS (advanced paediatric life support) course

See the course website for more information (www.apls.org.au).

EMST (early management of severe trauma) course

More details are available under the Skills Training section of the RACS website (www.racs.edu.au).

ACME (advanced complex medical emergencies) course

Simulation training has matured significantly in recent years. A number of senior FACEMs have been involved in the creation and running of this high-intensity course, and more details can be obtained from the College website (www.acem.org.au).

CCrISP (care of the critically ill surgical patient) course

This course runs along a similar three-day format to the EMST course and is compulsory for surgical trainees. Based on MET-type principles of early recognition and management of medical complications, this course has broad application to surgical and medical conditions and has instructors from all the critical care specialties, as well as senior surgeons. A particularly valuable aspect of this course is its strong emphasis on communication skills. More details are available under the Skills Training section of the RACS website (www.racs.edu.au).

EMSB (emergency management of severe burns) course

If trauma appeals to you and/or management of burns is something you need to be more familiar with, this course has it all. The course is run by the Australia and New Zealand Burn Association (ANZBA), and course dates and information can be obtained from the Health Care Professionals section of the ANZBA website (www.anzba.org.au).

Creating the right impression

However, the most important component of the impression you create is your attitude. Recall your inten tion to be a competent emergency medicine specialist and be one. Take each question you are asked as a lead to a discussion with a colleague. There will be no traps or hidden agendas. The examiners gen uinely want to hear what you know. Conversely, they don’t want to be argued with. Your responses should be considered, to the point and not waffly. Speak audibly at a pace you are comfortable with. If you are not sure what a question means, politely say so and it will be rephrased. Do not be concerned when the topic changes. Each new question is an opportunity for you to demonstrate your competence in another area and the examiners may be deliberately trying to lead you in order to maximise your overall score on their marking template.

Travel considerations

Coping with failure

If you are unsuccessful, you will be notified by mail of your marks in each section of the examination. You may also request further feedback from the Censor-in-Chief, who can discuss your performance with you via telephone in the weeks after the exam. Your DEMT(s) should also be able to debrief you and offer confidential counselling and support, as well as help you plan for the future.