Chapter 4 Preparation and staining methods for blood and bone marrow films

Preparation of blood films on slides

Manual Method

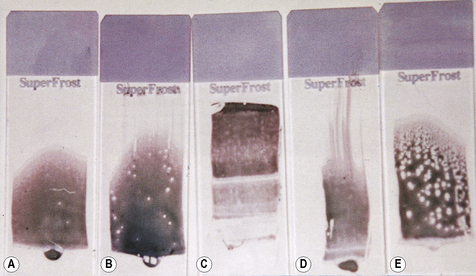

Place a small drop of blood in the centre line of a slide about 1 cm from one end. Then, without delay, place a spreader in front of the drop at an angle of about 30° to the slide and move it back to make contact with the drop. The drop should spread out quickly along the line of contact. With a steady movement of the hand, spread the drop of blood along the slide. The spreader must not be lifted off until the last trace of blood has been spread out; with a correctly sized drop, the film should be about 3 cm in length. It is important that the film of blood finishes at least 1 cm before the end of the slide (Fig. 4.1).

The ideal thickness is such that on microscopy there is some overlap of red cells throughout much of the film’s length (see p. 30). The leucocytes should be easily recognizable throughout most of the film. With poorly made films the leucocytes will be unevenly distributed, with monocytes and other large leucocytes being pushed to the end and the sides of the spread. An irregular streaky film will occur if the slide is greasy, and dust on the surface will cause patchy spots (Fig. 4.1).

Fixing Blood Films

To preserve the morphology of the cells, films must be fixed as described on p. 59. This must be done without delay, and the films should never be left unfixed for more than a few hours. If films are sent to the laboratory by post, it is essential that, when possible, they are thoroughly dried and fixed before dispatch.

Bone Marrow Films

The method for preparation of films of aspirated bone marrow is described on p. 126. They should be made without delay. Films must be thoroughly dry before they are fixed or artefactual changes will occur. At least one film should be fixed for a Perls’ stain on the initial bone marrow aspirate of each patient, and, if necessary, films should be fixed in the appropriate fixatives for special staining (Chapter 15); others should be fixed and stained with a Romanowsky stain as described later. Crushed bone marrow particles and touch preparations from trephine biopsy specimens can be stained in the same manner.

Staining blood and bone marrow films

Romanowsky stains are used universally for routine staining of blood films, and satisfactory results can be obtained. The remarkable property of the Romanowsky dyes of making subtle distinctions in shades of staining, and of staining granules differentially, depends on two components: azure B (trimethylthionin) and eosin Y (tetrabromo-fluorescein).1,2

The original Romanowsky combination was polychrome methylene blue and eosin. Several of the stains now used routinely that are based on azure B also include methylene blue, but the need for this is debatable. Its presence in the stain is thought by some to enhance the staining of nucleoli and polychromatic red cells; in its absence, normal neutrophil granules tend to stain heavily and may resemble ‘toxic granules’ in conventionally stained films.3

There are a number of causes of variation in staining. One of the main factors is the presence of contaminants in the commercial dyes and a simple combination of pure azure B and eosin Y might be considered preferable to the more complex stains because this ensures consistent results from batch to batch.1,4,5 However, in practice, absolutely pure dyes are expensive, and it is sufficient to ensure that the stains contain at least 80% of the appropriate dye.6 Among the Romanowsky stains now in use, Jenner is the simplest and Giemsa is the most complex. Leishman’s stain, which occupies an intermediate position, is still widely used in the routine staining of blood films, although the results are inferior to those obtained by the combined May–Grünwald–Giemsa, Jenner–Giemsa, and azure B–eosin Y methods. Wright’s stain, which is widely used in North America, gives results that are similar to those obtained with Leishman’s stain, whereas Wright–Giemsa is similar to May–Grünwald–Giemsa.

A pH to the alkaline side of neutrality accentuates the azure component at the expense of the eosin and vice versa. A pH of 6.8 is usually recommended for general use, but to some extent this depends on personal preference. (When looking for malaria parasites, a pH of 7.2 is recommended to see Schüffner’s dots.) To achieve a uniform pH, 50 ml of 66 mmol/l Sörensen’s phosphate buffer (see p. 622) may be added to each litre of the water used in diluting the stains and washing the films.

The mechanism by which certain components of a cell’s structure stain with particular dyes and other components fail to do so depends on complex differences in binding of the dyes to chemical structures and interactions between the dye molecules.7 Azure B is bound to anionic molecules, and eosin Y is bound to cationic sites on proteins.

Thus, the acidic groupings of the nucleic acids and proteins of the cell nuclei and cytoplasm of primitive cells determine their uptake of the basic dye azure B, and, conversely, the presence of basic groupings on the haemoglobin molecule results in its affinity for acidic dyes and its staining by eosin. The granules in the cytoplasm of neutrophil leucocytes are weakly stained by the azure complexes. Eosinophilic granules contain a spermine derivative with an alkaline grouping that stains strongly with the acidic component of the dye, whereas basophilic granules contain heparin, which has an affinity for the basic component of the dye. These effects depend on molar equilibrium between the two dyes in time-dependent reactions.2 DNA binds rapidly, RNA more slowly, and haemoglobin more slowly still; hence the need to have the correct azure B to eosin ratio to avoid contamination of the dyes and to stain for the right time. Standardized stains and staining method have been proposed (see p. 61).

The colour reactions of the Romanowsky effect are shown in Table 4.1; causes of variation in staining are given in Table 4.2.

Table 4.1 Colour responses of blood cells to Romanowsky staining

| Cellular component | Colour |

|---|---|

| Nuclei | |

| Chromatin | Purple |

| Nucleoli | Light blue |

| Cytoplasm | |

| Erythroblast | Dark blue |

| Erythrocyte | Dark pink |

| Reticulocyte | Grey-blue |

| Lymphocyte | Blue |

| Metamyelocyte | Pink |

| Monocyte | Grey-blue |

| Myelocyte | Pink |

| Neutrophil | Pink/orange |

| Promyelocyte | Blue |

| Basophil | Blue |

| Granules | |

| Promyelocyte (primary granules) | Red or purple |

| Basophil | Purple black |

| Eosinophil | Red-orange |

| Neutrophil | Purple |

| Toxic granules | Dark blue |

| Platelet | Purple |

| Other inclusions | |

| Auer body | Purple |

| Cabot ring | Purple |

| Howell–Jolly body | Purple |

| Döhle body | Light blue |

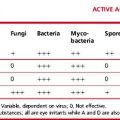

Table 4.2 Factors giving rise to faulty staining

| Appearances | Causes |

|---|---|

| Too blue | Incorrect preparation of stock, eosin concentration too low |

| Stock stain exposed to bright daylight | |

| Batch of stain solution overused | |

| Impure dyes | |

| Staining time too short | |

| Staining solution too acid | |

| Film too thick | |

| Inadequate time in buffer solution | |

| Too pink | Incorrect proportion of azure B:eosin Y |

| Impure dyes | |

| Buffer pH too low | |

| Excessive washing in buffer solution | |

| Pale staining | Old staining solution |

| Overused staining solution | |

| Incorrect preparation of stock | |

| Impure dyes, especially azure A and/or C | |

| High ambient temperature | |

| Neutrophil granules not stained | Insufficient azure B |

| Neutrophil granules dark blue/black (pseudo-toxic) | Excess azure B |

| Other stain anomalies | Various contaminating dyes and metal salts |

| Stain deposit on film | Stain solution left in uncovered jar |

| Stain solution not filtered | |

| Blue background | Inadequate fixation or prolonged storage before fixation |

| Blood collected into heparin as anticoagulant |

Preparation of Solutions of Romanowsky Dyes

Buffered Water

Make up 50 ml of 66 mmol/l Sörensen’s phosphate buffer of the required pH to 1 litre with water at a pH of 6.8 (see p. 622). An alternative buffer may be prepared from buffer tablets, which are available commercially. Solutions of the required pH are obtained by dissolving the tablets in water.

Staining methods

May–Grünwald–Giemsa Stain

When differentiation is complete, stand the slides upright to dry. This method is designed for staining a number of films at the same time. Single slides may be stained by flooding the slide with a combined fixative and staining solution (e.g. Leishman’s stain, discussed later), but it is important to ensure that the methanol used as fixative is completely water-free. As little as 1% water may affect the appearance of the films, and a higher water content causes gross changes (Fig. 4.2). The red cells will also be affected by traces of detergent on inadequately washed slides (see Fig. 26.5, p. 612).

Standardized Romanowsky Stain

A standardized Romanowsky stain2,5 based on a method with pure dyes has been proposed by the International Committee for Standardization in Haematology. It is useful for checking the performance of routine stains. The method is described fully in previous editions.

Automated Staining

Automatic staining machines are available that enable large batches of slides to be handled. They may be either stand-alone staining machines or a part of a large automated blood counting instrument. In many instances, the instrument spreads, fixes and stains blood films. Some automated instruments incorporating staining can only be programmed to prepare and stain a single film per sample. Others can prepare and stain multiple films from a single blood sample; this is useful for preparing slides for teaching large numbers of students. Some systems apply staining solutions to slides lying horizontally (flat-bed staining), whereas others either immerse a slide or slides in a bath of staining solution (‘dip-and-dunk’ technique) or spray stain onto slides in a cytocentrifuge. Problems include increased background staining, inadequate staining of neutrophil granules, degranulation of basophils and blue or green rather than pink staining of erythrocytes. These problems are usually related to the specific stains and staining protocols used rather than to the type of instrument, although flat-bed stainers are more likely to cause problems with stain deposit. However, as a rule, staining is satisfactory provided that reliable stains are used and there is careful control of the cycle time and other variables.8 Flat-bed stainers may not stain an entire film (e.g. a bone marrow film) if the film exceeds the standard length.

Rapid Staining Method

Field’s method9,10 was introduced to provide a quick method for staining thick films for malaria parasites (see below). With some modifications, it can be used fairly satisfactorily for the rapid staining of thin films. The stains are available commercially ready for use, or they can be prepared as follows.

Stains

Stain A (Polychromed Methylene Blue)

| Methylene blue | 1.3 g |

| Disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4.12H2O) | 12.6 g |

| Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) | 6.25 g |

| Water | 500 ml |

Stain B (Eosin)

| Eosin | 1.3 g |

| Disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4.12H2O) | 12.6 g |

| Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) | 6.25 g |

| Water | 500 ml |

Examination of wet blood film preparations

The examination of a drop of blood sealed between a slide and coverglass is sometimes of considerable value. The preparation may be examined in several ways: by ordinary illumination, by dark-ground or by Nomarski (interference) illumination. Chemically clean slides and coverglasses (see p. 623) should be used,* and the blood should be allowed to spread out thinly between them. If the glass surfaces are free from dust, the blood will spread out spontaneously, and pressure, which is undesirable, should not be necessary. The edges of the preparation may be sealed with a melted mixture of equal parts of petroleum jelly and paraffin wax or with nail varnish.

Red Cells

Anisocytosis and poikilocytosis can be recognized in ‘wet’ preparations of blood, but the tendency to crenation and the formation of rouleaux tend to make observations on shape changes rather difficult. Such changes can best be studied in a wet preparation after fixation. For this, dilute a sample of freshly collected heparinized or EDTA-anticoagulated blood in 10 volumes of iso-osmotic phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (see p. 622) and immediately fix with an equal volume of 0.3% glutaraldehyde in iso-osmotic phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. After standing for 5 min, add 1 drop of this suspension to 4 drops of glycerol and place 1–2 drops on a glass slide that is then sealed.11

Pitting occurs normally in less than 2% of the red cells; an increase of more than 4% is an indication of splenic dysfunction. The pits are readily identified by Nomarski illumination or electron microscopy when they have the appearance of small crater-like indentations on the cell surface.12

Sickling of red cells in ‘wet’ preparations of blood is described in Chapter 14.

Crystals of haemoglobin C can be demonstrated by incubating a sample of blood with an equal volume of 30 g/l sodium chloride for 4 h at 37°C.13 In blood from patients with haemoglobin C disease this induces formation of intracellular haemoglobin C crystals, large, clear structures that are well shown when the preparation is then stained by any Romanowsky stain.13 They can also be demonstrated in red cells from patients with compound heterozygosity for haemoglobins S and C.

Cryoglobulinaemia

This is a useful test when an automated blood count gives anomalous results with spuriously elevated white blood cell and platelet counts.14

Separation and concentration of blood cells

Making a Buffy Coat Preparation

As an alternative to centrifugation, the blood may be allowed to sediment by placing the tube vertically on the bench without disturbance, with or without the help of sedimentation-enhancing agents such as fibrinogen, dextran, gum acacia, Ficoll (Pharmacia) or methylcellulose.15 Bøyum’s reagent16 (methylcellulose and sodium metrizoate) is particularly suitable for obtaining leucocyte preparations with minimal red cell contamination.

Utility of the Buffy Coat

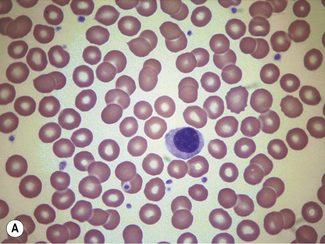

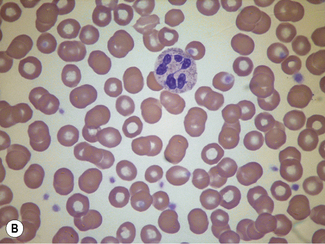

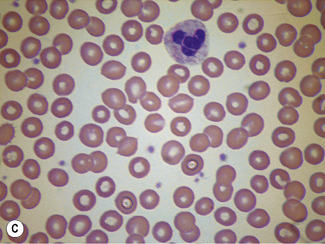

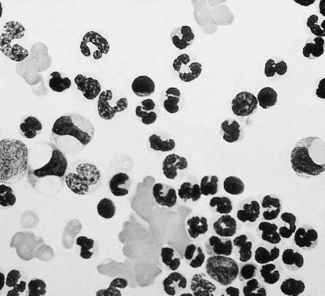

It is well known that atypical or primitive blood cells circulate in small numbers in the peripheral blood in health. Thus, atypical mononuclear cells, metamyelocytes and megakaryocytes may be found. Even promyelocytes, blasts and nucleated red cells may occasionally be seen but only in very small numbers. Efrati and Rozenszajn17 described a method for the quantitative assessment of the numbers of atypical cells in normal blood and gave figures for the incidence of megakaryocyte fragments (e.g. mean 21.8 per 1 ml of blood) and of atypical mononuclear cells and metamyelocytes and myelocytes. In cord blood, the incidence of all types of primitive cells is considerably greater.18

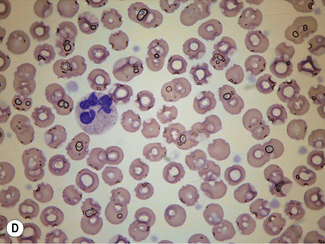

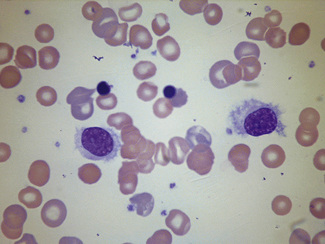

In disease, abnormal cells may be seen in buffy coat preparations in much larger numbers than in films of whole blood (Fig. 4.3). Another example, for instance, is megakaryocytes and immature cells of the granulocyte series found in relatively large numbers in disseminated carcinoma.19 Megaloblasts, if present, may help in the diagnosis of a megaloblastic anaemia. Ring sideroblasts may be seen in patients with sideroblastic anaemia; their presence can be confirmed with a Perls’ stain. Haemophagocytosis, which is more often observed in the bone marrow, may also sometimes be demonstrated in buffy coat preparations.20 Erythrophagocytosis may be conspicuous in cases of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (Fig. 4.4). In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) a few LE cells may be found, but this is not the best way to demonstrate LE cells; moreover, the detection of LE cells for the diagnosis of SLE has been supplanted by immunological tests for the detection of antinuclear or anti-DNA antibodies.

Separation of Specific Cell Populations

It is now possible to identify specific cell populations by flow cytometric immunophenotyping, and the need for separation of mononuclear cells from blood has diminished. However, differences in density of cells can also be used to separate individual cell types, using gradient solutions of selected specific gravity.16,21 This is also a useful method for use in leucocyte imaging with radio-isotope-labelled neutrophils (see p. 388). A simple convenient technique has been described for layering the blood or bone marrow over the density preparations.22 The median density values for the main haemopoietic cells are as follows:

| Erythrocytes | 1100 |

| Eosinophils | 1090 |

| Neutrophils | 1085 |

| Myelocytes | 1075 |

| Lymphocytes | 1070 |

| Monocytes | 1064 |

| Myeloblasts | 1062 |

| Platelets | 1035 |

Parasites detectable in blood, bone marrow or splenic aspirates

There are now a number of screening tests for diagnosing malaria based on the detection of malarial antigens (see Chapter 6). However, the essential method for a definitive diagnosis remains the finding of parasites in a blood film and the identification of the species by morphology.23,24 Only brief outlines of the microscopic diagnoses are given in this chapter. For more detailed accounts, readers are referred to a parasitology textbook. In addition to the plasmodia that give rise to malaria, the other important parasites to be found in the blood are leishmaniae, babesiae, trypanosomes and microfilaria.

Low levels of parasitaemia detected by immunological tests may be missed by microscopy and proficiency testing studies have demonstrated the need for all laboratories, and especially those lacking expertise, to take part in external quality control programmes and to refer problematic cases to more experienced centres.25,26

Examination of blood films for parasites

Staining Thick Films

Field’s method of staining9,10 is quick and usually satisfactory for thick films, but the method is not practical for staining large numbers of films; for this purpose the Giemsa, Leishman or azure B–eosin Y methods are more suitable. Careful attention to pH is critical for satisfactory staining of parasites.

Giemsa’s Stain

Azure B–Eosin Y Stain

Sometimes when thick films are stained, they become overlaid by a residue of stain or spoilt by the envelopes of the lysed red cells. These defects can be minimized by adding 0.1% Triton X-100 to the buffer before diluting the stock stain.27 An alternative, but more laborious, method is to lyse 1 volume of blood with 3 volumes of 1% saponin in saline for 10 min, then centrifuge for 5 min, decant the supernatant, and make films from the residual pellet.28

1 Wittekind D. On the nature of Romanowsky dyes and the Romanowsky Giemsa effect. Clin Lab Haematol. 1979;1:247-262.

2 Horobin R.W., Walter K.J. Understanding Romanowsky staining. I. the Romanowsky-Giemsa effect in blood smears. Azure B-eosin as a substitute for May–Grünwald–Giemsa and Jenner–Giemsa stains. Microsc Acta. 1987;79:153-156.

3 Marshall P.N. Romanowsky-type stains in haematology. Histochem J. 1978;10:1-29.

4 Wittekind D.H., Kretschmer V., Sohmer I. Azure B-eosin Y stain as the standard Romanowsky-Giemsa stain. Br J Haematol. 1982;5:391-393.

5 International Committee for Standardization in Haematology. ICSH reference method for staining of blood and bone marrow films by azure B and eosin Y (Romanowsky stain). Br J Haematol. 1984;57:707-710.

6 Schenk E.A., Willis C.T. Note from the Biological Stain Commission: certification of Wright stain solution. Stain Technol. 1989;64:152-153.

7 Wittekind D.H. On the nature of Romanowsky-Giemsa staining and its significance for cytochemistry and histochemistry: an overall view. Histochem J. 1983;15:1029-1047.

8 Hayashi M., Gauthier S., Tatsumi N. Evaluation of an automated slide preparation and staining unit. Sysmex Journal International. 1996;6:63-69.

9 Field J.W. The morphology of malarial parasites in thick blood films. IV. The identification of species and phase. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1940;34:405-414. –1941

10 Field J.W. Further notes on a method of staining malarial parasites in thick films. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1941;35:35. –1942

11 Zipursky A., Brown E., Palko J., et al. The erythrocyte differential count in newborn infants. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1983;5:45-51.

12 Sills R.H. Hyposplenism. In: Pochedly C., Sills R.H., Schwartz A.D., editors. Disorders of the Spleen. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1989.

13 Nagel R.L., Fabry M.E., Steinberg M.H. The paradox of hemoglobin SC disease. Blood Rev. 2003;17:167-178.

14 Fohlen-Walter A., Jacob C., Lacompte T., et al. Laboratory identification of cryoglobulinema from automated blood cell counts, fresh blood samples, and blood films. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:606-614.

15 Bloemendal H., editor. Cell Separation Methods. Amsterdam: Elsevier-North Holland, 1977.

16 Bøyum A. Separation of lymphocytes, granulocytes and monocytes from human blood using iodinated density gradient media. Methods Enzymol. 1984;108:88-102.

17 Efrati P., Rozenszajn L. The morphology of buffy coat in normal human adults. Blood. 1960;16:1012-1019.

18 Efrati P., Rozenszajn L., Shapira E. The morphology of buffy coat from cord blood of normal human newborns. Blood. 1961;17:497-503.

19 Romsdahl M.M., McGrew E.A., McGrath R.G., et al. Hematopoietic nucleated cells in the peripheral venous blood of patients with carcinoma. Cancer (Philadelphia). 1964;17:1400-1404.

20 Linn Y.C., Tien S.L., Lim L.C., et al. Haematophagocytosis in bone marrow aspirate: a review of the clinical course of 10 cases. Acta Haematol. 1995;94:182-191.

21 Ali F.M.K. Separation of Human Blood and Bone Marrow Cells. Bristol: Wright; 1986.

22 Islam A. A new, fast and convenient method for layering blood or bone marrow over density gradient medium. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:686-688.

23 Hänscheid T. Diagnosis of malaria: a review of alternatives to conventional microscopy. Clin Lab Haematol. 1999;21:235-245.

24 Moody A.H., Chiodini P.L. Methods for the detection of blood parasites. Clin Lab Haematol. 2000;22:189-202.

25 Thomson S.T., Lohmann R.C., Crawford L., et al. External quality assessment in the examination of blood films for malaria parasites within Ontario, Canada. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:57-60.

26 Bell D., GO R., Miguel C., et al. Diagnosis of malaria in a remote area of the Philippines: comparison of techniques and their acceptance by health workers and the community. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:933-941.

27 Melvin D.M., Brooke M.M. Triton X-100 in Giemsa staining of blood parasites. Stain Technol. 1955;30:269-275.

28 Gleeson R.M. An improved method for thick film preparation using saponin as a lysing agent. Clin Lab Haematol. 1997;19:249-251.