Chapter 10 Preoperative medical problems in surgical patients

10.1 Introduction

The most common chronic medical problems in surgical patients are hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive airways disease, diabetes mellitus and alcoholic liver disease. Other disorders encountered include chronic renal injury, anaemia, cerebral vascular disease and disorders of haemostasis. Many patients have multiple medical conditions, particularly when there is a history of smoking and excessive consumption of alcohol. Many patients have associated depression or anxiety. Thus, when assessing any patient with a surgical problem, an adequate general history and physical examination is essential. Identifying associated medical problems at the first interview gives the best chance for them to be controlled prior to operation.

10.2 Assessing patients for surgery

Progress in anaesthetic and surgical practice has enabled more and more patients, over wider extremes of age, with more and more complex systemic diseases, to be treated by major surgery. Making the patient safe for surgery (Box 10.1) starts with detecting concurrent medical illness in the systems review and physical examination. Evaluation and subsequent treatment of major risk factors are important steps in the reduction of surgical mortality and morbidity. Surgical risk is the probability of mortality or complications associated with surgery or anaesthesia. Risk factors can be related to the procedure or to the patient or both.

Patient-related risk factors to be aware of include:

Procedure-related risk factors may be anaesthesia-related or operation-related and vary with:

Grading of surgical and anaesthetic risk

Patients can be graded into five classes according to the severity of associated systemic diseases and of the surgical condition, as recommended by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA classification — Table 10.1). The suffix E is added to each class for those having emergency operations.

| Class 1 | Normal healthy patients for age |

| Class 2 | Mild systemic disease |

| Class 3 | More severe compensated systemic disease that limits activity but is not incapacitating |

| Class 4 | Uncompensated incapacitating systemic disease — a constant threat to life |

| Class 5 | Moribund — not expected to survive 24 hours with or without operation |

Emergency — precede the number with an E

Evaluation of the elderly asymptomatic patient

Ageing increases the likelihood of asymptomatic systemic illness and screening tests are therefore more stringently applied to older, apparently healthy patients. Elderly patients (aged over 70 years) have increased mortality and complication rates for surgical procedures compared with young patients. Problems are: reduced functional reserves; coexisting cardiac and pulmonary disease; renal dysfunction; poor tolerance of blood loss and greater sensitivity to analgesics; sedatives; and anaesthetic agents.

Investigations and diagnostic (screening) tests before surgery

Other tests

In patients aged over 60 years serum glucose, renal function tests and tests of haemostatic disorders — prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), as well as any history of anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent ingestion — should be added (Box 10.2). Preoperative routine tests in those aged over 60 years should include ECG, chest X-ray, liver function tests, renal function tests, prothrombin time, APTT, platelet count and full blood count.

Box 10.2

Assessment for surgery: preoperative requirements and tests

Young, healthy patients (<60 years), class I surgical risk

Blood type and screen for major surgery

Consider autologous transfusion

Healthy patients 60–70 years, class I surgical risk

Blood type and screen (cross-match and reserve blood if expected loss >2 units)

10.3 Cardiac disease

Using noninvasive methods, Goldman,1 in the USA, proposed a concise system using nine identified risk factors for estimating the perioperative cardiac risk index (Box 10.3). Patient-related risk factors are: age over 70 years, previous myocardial infarction, heart failure, arrhythmias, ECG abnormalities, aortic stenosis and associated general medical illness. Procedure-related risk factors include intrathoracic, intraperitoneal and aortic surgery and emergency operations. Points are assigned for risk factors and patients are divided into classes with ascending scores. Mortality and morbidity rise steeply and progressively from class 1 to 4.

Box 10.3

Cardiac risk index: high risk factors

Myocardial infarction <6 months ago

Elective surgery, however, is contraindicated when there is angina of recent onset, unstable angina, recent myocardial infarction, severe aortic stenosis, a high degree of atrioventricular heart block, severe hypertension and untreated congestive cardiac failure. Within three months of an acute infarct (which in 50% of cases is silent), the reinfarction rate after operation is 25%, with a perioperative mortality of more than 50%. The added risk of surgery stabilises at 5% after six months.

Cardiac patients are particularly sensitive to a fall in venous return (and thus coronary perfusion) and to hypoxia, especially when they are also anaemic (Box 10.4). In most cases hypovolaemia is the cause of diminished venous return during surgery but septicaemia, vasodilator drugs and hypercapnia are other causes. Occasionally, the pneumoperitoneum induced for laparoscopic abdominal procedures may reduce venous return. Patients with chronic obstructive airways disease tend to accumulate pulmonary interstitial fluid and, unless care is taken in high-risk patients, diminished pulmonary gas transfer will produce hypoxia and increase the danger of cardiac complications. Postoperative pain leads to increased catecholamine release and an increased incidence of arrhythmias.

History

Patients with recent onset angina, unstable angina and crescendo angina are identified. The evidence for recent myocardial infarction should be reviewed and the time from infarct noted. A history of palpitations suggests the presence of potentially serious arrhythmias or serious conduction defects. A history of exertional dyspnoea, cough, fatigue, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea orthopnoea and leg oedema suggests the diagnosis of congestive cardiac failure or that heart failure under treatment is poorly controlled. The major risk factors associated with ischaemic disease are outlined in Box 10.5. Anaemia may unmask anginal symptoms. Most of the risk factors (apart from anaemia) will require considerable time to reverse.

Diagnostic and treatment plan

Invasive monitoring

Invasive monitoring is indicated in elective as well as emergency surgery for patients with diminished cardiac reserve. This applies particularly to major surgery in elderly patients and those with severe coronary artery disease, conduction defects or severe aortic stenosis. A radial arterial line is used to monitor arterial blood pressure. Monitoring of the left atrial pressure and pulmonary artery pressures with a Swan-Ganz catheter and serial measurement of oxygen tension in the blood and arteriovenous oxygen differences are sometimes necessary. Thermodilution techniques using a Swan-Ganz catheter, together with measurement of oxygen consumption and CO2 production, can provide serial monitoring of cardiac output, stroke volume and ventilatory equivalents of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Many such patients are also at high risk of respiratory failure.

Common cardiac problems

It is important to control certain cardiovascular problems before operation (Box 10.6).

Hypertension

Elective surgery poses little danger to patients with uncomplicated hypertension if the diastolic blood pressure is less than 100 mmHg, provided there is no heart failure and renal function is normal. With modern antihypertensives most patients can be maintained on their treatment up to and including the day of surgery. Postoperative hypotension may occur with catecholamine depletion secondary to antihypertensive agents such as methyldopa. It is essential to check for the presence of hypokalaemia before surgery in patients who have been treated with thiazide diuretics. Good anaesthetic management is a more important factor than preoperative adjustment of drug dosages in the prevention of hypertensive complications.

10.4 Respiratory disease

Diagnostic plan

Spirometry and arterial blood gas estimation are mandatory in patients with evidence of incipient respiratory failure (limitation in exercise tolerance because of exertional dyspnoea and a forced expiration time of greater than five seconds). Testing is also indicated in: patients undergoing major surgery of the upper abdomen or chest; the elderly; patients with cough, sputum, wheezing or asthma; and those with a history of heavy smoking (Box 10.7).

Box 10.7

Indications for preoperative lung function tests

History of exertional dyspnoea

History of cough, sputum, wheeze

Postoperative respiratory failure is almost inevitable (Box 10.8) if:

10.6 Alcoholic liver disease

Alcoholism can be difficult to detect. The amount consumed and length of history are often concealed. In most cases, signs of liver disease can be found that suggest the diagnosis. The degree of liver damage is directly related to the amount of alcohol consumed. Alcoholic liver disease is a common associated problem in both emergency and elective surgical patients. Elective surgery should be delayed in the presence of moderate or severe alcoholic liver disease. In most patients general health and liver function can be much improved by a period of abstinence and chest physiotherapy, especially in those patients who smoke heavily. Emergency surgery often causes a decompensation in liver function in patients with severe cirrhosis, especially with surgical conditions associated with sepsis, bleeding, electrolyte disturbances (hypokalaemia, metabolic alkalosis and acidosis), hypoxia and hypoglycaemia. Sedatives, narcotics, tranquillisers and antibiotics require very careful control of dosage. Most are metabolised and excreted by the liver; portal-systemic venous shunting due to liver disease results in oral agents having an effective 10–20-fold increase in systemic drug delivery, requiring reduction of oral drug dosage.

Complications arising from alcoholic liver disease

There are a number of major problems and complications that can arise in the surgical patient with alcoholic liver disease (Box 10.9). Each is explained in turn.

Box 10.9

Problems associated with alcoholic liver disease

Malnutrition — vitamin deficiency

Operative or gastrointestinal bleeding (portal hypertension)

Sepsis is increased because of malnutrition, poor hygiene and immunosuppression.

History and physical examination

Examination may reveal few signs, apart from hepatomegaly. A dishevelled appearance and alcoholic facies may arouse suspicion of the diagnosis. Systemic signs of liver disease include palmar erythema, leuconychia, spider naevi, loss of body hair, gynaecomastia, testicular atrophy, evidence of vitamin deficiencies, glossitis and cheilosis. Overt signs of liver failure include jaundice, ascites, wasting and encephalopathy. Jaundice can occur early from alcoholic hepatitis or cholestasis, often precipitated by a drinking spree. Wernicke’s encephalopathy (a reversible brain syndrome due to thiamine deficiency) and Korsakov’s psychosis (in which brain damage is usually irreversible) may also be evident. Sudden deterioration in liver function may sometimes be due to the development of hepatoma. Congestive heart failure is common. Splenomegaly, a major sign of portal hypertension, may be detectable.

Diagnostic plan

Routine tests (Box 10.10) include blood examination, liver function tests including coagulation screening, serum amylase, chest X-ray and ECG. The level of serum albumin is the best general measure of prognosis. In many cases respiratory function tests are necessary because of significant obstructive airways disease. Abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT scan and liver biopsy may be indicated when the diagnosis is in doubt.

Treatment plan

10.7 Chronic renal disease

Treatment plan

Important aspects of preoperative preparation in patients with chronic renal failure are summarised in Box 10.12. Hypertension and urinary tract infection may need treatment before elective surgery can proceed. Unless absolutely necessary, urinary catheterisation should be avoided. Transurethral prostectomy may be necessary to relieve bladder neck obstruction before elective surgery. Patients with anaemia or renal failure survive with quite low haemoglobin levels, due to an increase in 2, 3–diphosphoglycerate (2, 3–DPG) promoting better transfer of oxygen at the tissue level. Injudicious blood transfusion in a normovolaemic haemodiluted patient may reduce renal blood flow by increasing blood viscosity and can precipitate an exacerbation of renal failure. Thus a haemoglobin level of 8–9 g/dL in patients with chronic renal disease may be adequate for major surgery and not require transfusion. As many drugs are nephrotoxic, particular care must be taken with prescribing (Box 10.13).

Box 10.12

Preoperative preparation of patients with chronic renal disease

Watch for drug nephrotoxicity — particularly nephrotoxic antibiotics.

Box 10.13

Nephrotoxic drugs

Antibiotics: aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, amphotericin B, tetracycline, cephalosporins

As each nephron either functions normally or ceases to function with disease (intact nephron principle), creatinine clearance (Ccr) is an excellent marker of the degree of dose reduction required. If the Ccr is 50% of normal, all drugs cleared by the kidney need 50% reduction in dose. Drugs that are the worst offenders are aminoglycoside antibiotics (gentamicin), analgesics such as phenacetin and NSAIDs, oral hypoglycaemic agents and methoxyflurane. As digoxin is mainly excreted by the kidneys, digitalis toxicity is a common problem in patients with chronic renal failure. Examples of drugs mainly cleared by renal mechanisms are shown in Box 10.14.

In patients not requiring maintenance dialysis and after cautious correction of severe anaemia, management concentrates on preoperative hydration and strict attention to fluid balance during and after surgery. High-risk patients (major vascular surgery, jaundiced and diabetic patients, and those with chronic renal insufficiency) are also given a slow infusion of a solute diuretic during surgery (mannitol 20 g) with careful monitoring of urine output.

Acute tubular necrosis may occur, especially in the high-risk patient, after emergency or complicated surgery. Oliguria in these patients commonly has a correctable hypovolaemic prerenal component to it. Bladder neck obstruction should always be excluded. In patients with a poor response to a fluid load or diuretic measures and a raised urinary sodium, where incipient acute renal failure is likely to be present, preparations for dialysis should be taken as soon as possible (Box 10.15). Extrarenal factors that may contribute to deterioration of renal failure — such as sepsis, fluid and electrolyte disturbances, drug toxicity and inadequate nutrition — should also receive careful attention.

10.8 Haemostatic and haemopoietic disorders

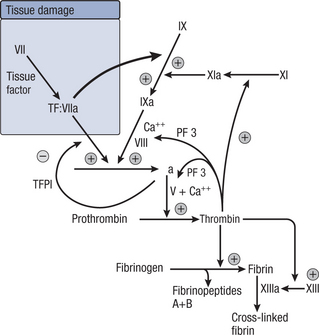

Sometimes unexpected bleeding can be traced to a generalised defect in haemostasis (Box 10.16). The most common defect of coagulation encountered in surgical practice is prior treatment with oral anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. Precise diagnosis and correct management require knowledge of the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways to fibrin formation (Fig 10.1) and the formation and the function of platelets. The initial response when a vessel is divided is for it to constrict (Box 10.16). This, combined with platelet aggregation and adherence and plasma coagulation, stops the bleeding. Platelets adhere to an endothelial defect and react with collagen to perpetuate vasoconstriction and produce further platelet aggregation. Exposure of plasma to connective tissue activates specific plasma enzymes and clotting factors, initiating the coagulation cascade. This generates thrombin and ultimately leads to the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin clot, reinforcing the friable platelet aggregate. Initiation of coagulation also leads to the activation of plasminogen that releases plasmin, a fibrinolytic factor. Plasmin is a natural defence against pathological extension of fibrin deposition.

Common causes

Clinical assessment

Diagnostic plan

Tests relating to coagulation, platelet function and vascular abnormalities include the following.

One-stage prothrombin time (PT)

This measures the time in seconds required to form a clot in citrated plasma after calcium and a standardised tissue thromboplastin have been added. It thus reflects the extrinsic clotting system from factor VII through the common pathway involving prothrombin and fibrinogen. It is most sensitive to factor VII deficiency and is the standard method of monitoring anticoagulant treatment with vitamin K antagonists and in detecting problems in patients with liver failure. The international normalised ratio (INR) is used to assess the control of oral anticoagulant treatment. It represents the ratio of the patient’s PT to a normal control based on an international reference thromboplastin, which ensures standardisation of anticoagulation between different centres.

Treatment plan

1 Patients on oral anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents

Aspirin and/or clopidogrel ingestion is often a factor in perioperative bleeding. Both reduce the capacity of platelets to aggregate. Where possible they should both be stopped at least five to seven days prior to elective surgery. Patients at high risk for arterial thrombosis (e.g. those with a drug-eluting coronary artery stent in situ) should be converted to heparin or clexane and managed as above during the perioperative period. The antiplatelet agents may be recommenced once oral intake has been re-established. For emergency surgery, it may be impossible to cease aspirin and/or clopidogrel in advance of the operation. If excessive bleeding is anticipated or occurs in this situation a platelet transfusion may be required.

4 Consumption coagulopathy

Consumption of clotting factors (including platelets) in the microcirculation may occur in the massively injured patient with tissue necrosis and sepsis, especially when compounded by massive transfusion of banked blood, which is poor in platelets and in labile factors V and VIII (Table 10.2).

Table 10.2 Changes during bank storage of whole blood at 4°C after two weeks

| Plasma levels | |

| Hydrogen ion | 25 mmol/L |

| Citrate | 5 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 20–30 mmol/L |

| Ammonia | 1 mg % |

| Free haemoglobin | 20 mg % |

| Particulate and antigenic debris | |

| Dead leucocytes — HLA | |

| Dead platelets | |

| Plasma protein antigens | |

| Red cells | |

| Early loss post-transfusion | 20% |

| 2,3–DPG | Nil |

| ATP | Very low |

| Osmotic fragility | Increased |

| Coagulation factors | |

| Factor V, VIII, IX | 10–20% or less |

| Platelets | Nil |

| Calcium | All chelated with citrate |

| Fibrinogen | Relatively normal |

5 Haemophilia, Christmas disease and Von Willebrand’s disease

Haemophilia A is an inherited sex-linked recessive trait that is associated with a deficiency of factor VIII (antihaemophilic globulin). Platelet function is unimpaired but the platelet clot is not reinforced by fibrin. The common clinical manifestation is bleeding into joints and soft tissues. Surgery should be avoided if possible but can be covered with increased safety by administration of concentrated factor VIII.

10.9 Anaemia

Treatment plan

In patients with megaloblastic anaemia surgery should be deferred, if possible, until specific therapy such as vitamin B12 or folic acid has repaired the generalised tissue defect. In these cases transfusion alone may not render surgery safe, as protein metabolism of all cells is affected by the vitamin deficiency that causes the macrocytic anaemia. Adequate tissue levels can be achieved with one to two weeks’ oral treatment with vitamin B12 or folic acid or both.

10.10 Diabetes mellitus

Diagnostic and treatment plans

Diabetes mellitus should be brought under control prior to operation (Box 10.17).

Box 10.17

Preoperative management: diabetes mellitus

Prevention of hypoglycaemia from inadequate carbohydrate intake is more important than prevention of ketosis from diabetes.

Prevention of hypoglycaemia from inadequate carbohydrate intake is more important than prevention of ketosis from diabetes.Ideally any operation should be scheduled early in the day, following the normal nocturnal fast. Metformin should be ceased 24 hours prior to surgery due to the risk of lactic acidosis. All other oral hypoglycaemic agents (e.g. sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, acarbose) should be ceased when the patient is fasting. Insulin-dependent diabetic patients should have their morning dose of insulin withheld or modified depending on their regimen of insulin and timing of surgery to a short-acting insulin and then be managed by a CII. Diabetes diagnosed in the perioperative period is best managed with insulin delivered as a CII. Treatment with insulin should commence when the blood sugar is greater than 10 mmol/L.

10.11 Mental health problems

Less immediately apparent is the fact that somatic symptoms are often the first presentation of psychiatric disorders. Physical diseases are respectable, but many patients and some doctors consider that mental health disorders are not. Therefore, patients often present to doctors with somatic symptoms that are used as tickets of entry when their primary disorders are emotional and behavioural. Depressed and anxious patients often present in this way, concentrating on a physical symptom such as weight loss (Ch 7.13) or bodily discomfort rather than the basic depression or anxiety state. If the doctor fails to recognise the underlying psychiatric basis of the presenting symptoms, a fruitless and potentially endless series of investigations may be embarked on in an attempt to find an organic basis for increasingly vague symptoms. Alternatively, the doctor must avoid becoming angry with the patient for what is taken to be evasiveness and failure to cooperate. Discernment, tact and empathy are required from the doctor in coming to the correct diagnosis. Some of the commoner problems encountered are discussed below and their management will often require professional assistance to resolve.

Clinical states

Anxiety disorders

In anxiety disorders, the anxious affect and mood are sustained despite absence of real threat. Anxiety syndromes may produce unformulated apprehension, gross motor restlessness (agitation) and panic attacks. Chronic symptoms consist of feelings of impending doom and accompanying powerlessness to prevent this, inability to perceive the unreality of the threat, persistent high tension and exhaustive readiness. Somatic symptoms are common. They include band-like headache, muscle aches and pains, palpitations, tremor, epigastric discomfort, belching, tingling and cramps in the legs and hands due to hyperventilation, sweating, and urinary and sexual dysfunctions. Depersonalisation (the feeling of being an impotent spectator of one’s own actions) is common. Inability to sleep and fear of travelling or going out alone can also occur. The symptoms may occur acutely, as in panic disorder, or chronically as in generalised anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Organic mental syndromes

Delirium

Delirium is suspected if the patient has fluctuating attention during history-taking or has difficult in recounting the history coherently. Confusion may be precipitated, particularly in elderly patients, by the change from a familiar home environment with a fixed daily routine to the unfamiliar and disturbing environment of the hospital ward. Confusion is often worse at night.

Common causes of delirium in hospitalised surgical patients include:

Causes of dementia

10.12 Additional preoperative preparation

Additional preoperative preparation must attend to certain factors that are specific for individual operations and diseases (Boxes 10.18–10.24). Patients with ASA classes 3 to 5 will require baseline tests for appropriate systemic disorders.

Box 10.18A

Preoperative preparation: oesophageal surgery

Improve oral hygiene and control dental sepsis.

Chest physiotherapy and antibiotics for chronic bronchitis or aspiration pneumonitis.

Correct anaemia and malnutrition. Consider preoperative enteral or parenteral feeding.

Box 10.18B

Preoperative preparation: gastroduodenal surgery

Correct associated problems of anaemia, metabolic alkalosis and hypokalaemia, and malnutrition.

Preoperative gastric lavage for pyloric stenosis.

Chest physiotherapy to control obstructive airways disease.

Preoperative proton pump inhibitors to control painful ulceration.

Box 10.19A

Preoperative preparation: chronic liver disease

Prevent or control encephalopathy by emptying the gut of protein and altering the gut flora.

Box 10.19B

Preoperative preparation: jaundiced patient

Prevent renal injury by perioperative hydration and maintaining an adequate urine output.

Box 10.20

Preoperative preparation: colorectal surgery

Diagnose and correct anaemia and hypokalaemia.

Prevent sepsis by prophylactic antibiotics and mechanical bowel preparation.

Preoperative colonoscopy to exclude synchronous cancer and to remove adenomas.

Prepare the patient for the possibility or certainty of a stoma.

Box 10.21

Preoperative preparation: urological surgery

Indwelling catheter or suprapubic cystostomy to relieve obstruction.

Control urinary tract infection.

Box 10.22

Preoperative preparation: vascular surgery

Prophylactic antibiotics and careful skin preparation, especially in the patient with ischaemia.

Box 10.23

Preoperative preparation: thyroid surgery

Ensure the patient is euthyroid on antithyroid medication.

Indirect laryngoscopy to check vocal cord movement.

Serum calcium and TFTs as preoperative baseline tests.

Image the neck and thoracic inlet to exclude tracheal compression by intrathoracic goitre.