Chapter 56

Preoperative Cardiac Evaluation

1. What is the natural history of perioperative cardiac morbidity?

2. What is the cause of perioperative cardiac morbidity?

3. What are the strongest predictors of perioperative cardiac events?

For some specific patients, surgery represents a very high risk of cardiac complications and either therapy should be initiated preoperatively or the benefits of surgery must significantly outweigh the risks if the decision is to proceed to surgery. According to the 2009 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation, active cardiac conditions for which the patient should undergo evaluation and treatment before noncardiac surgery include unstable coronary syndromes, active heart failure, severe valvular disease, and severe arrhythmias. Specific conditions within these general categories are shown in Table 56-1. Analysis of administrative data suggests that the elevated risk of a recent MI continues for at least the first 60 days.

TABLE 56-1

ACTIVE CARDIAC CONDITIONS FOR WHICH THE PATIENT SHOULD UNDERGO EVALUATION AND TREATMENT BEFORE NONCARDIAC SURGERY (CLASS I, LEVEL OF EVIDENCE B)

| CONDITION | EXAMPLES |

| Unstable coronary syndromes | Unstable or severe angina∗ (CCS class III or IV)† |

| Recent MI‡ | |

| Decompensated HF (NYHA functional class IV; worsening or new-onset HF) | |

| Significant arrhythmias | High-grade atrioventricular block |

| Mobitz II atrioventricular block | |

| Third-degree atrioventricular heart block | |

| Symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias | |

| Supraventricular arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation) with uncontrolled ventricular rate (HR > 100 beats/min at rest) | |

| Symptomatic bradycardia | |

| Newly recognized ventricular tachycardia | |

| Severe valvular disease | Severe aortic stenosis (mean pressure gradient >40 mm Hg, aortic valve area <1.0 cm2, or symptomatic) |

| Symptomatic mitral stenosis (progressive dyspnea on exertion, exertional presyncope, or HF) |

∗According to Campeau L: Grading of angina pectoris [letter]. Circulation 54:522-523

†May include stable angina in patients who are unusually sedentary.

‡The American College of Cardiology National Database Library defines recent MI as more than 7 days but less than or equal to 1 month (within 30 days).

Modified from Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al: ACC/AHA guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary, J Am Coll Cardiol 50:1716, 2007.

4. What is the revised cardiac risk index (RCRI) and how is it used clinically?

History of congestive heart failure

History of congestive heart failure

History of cerebrovascular disease

History of cerebrovascular disease

5. What is the importance of exercise capacity?

6. What is the influence of the surgical procedure on the decision to perform further diagnostic testing?

In all patients, regardless of the type of surgery, determination of the presence of active cardiac conditions is first and foremost, because proceeding to surgery should only be done after assessing and potentially treating these conditions. Low-risk surgeries (those associated with a perioperative cardiac morbidity and mortality less than 1%) rarely, if ever, require a change in management based on the results of a diagnostic test. The most common such procedures are those performed on an outpatient basis. Multiple studies have focused on patients undergoing vascular surgery, particularly open aortic and lower extremity revascularization. Therefore, these patients are treated uniquely in the assessment of the need to perform diagnostic testing, based on the extensive evidence and the high perioperative cardiac morbidity and mortality, often in the range of 5% or greater. In the intermediate group of procedures, a gradation of risk is based on the specific surgical procedures and the institution-specific risk is critical to determine if further diagnostic testing would add value. For example, increased surgical volume is associated with lower perioperative risk, and preoperative testing may not lead to changes in management in such institutions.

7. How do the ACCF/AHA guidelines suggest an approach to preoperative evaluation?

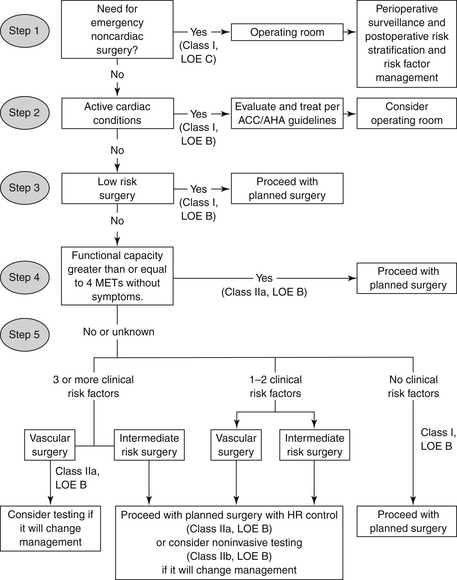

The algorithm from the 2009 guidelines can be found in Figure 56-1. Importantly, any decision to perform diagnostic testing based on the algorithm must incorporate the value of the information to change perioperative management. Changes in management can include the decision to undergo coronary revascularization, but may also include decisions by the patient to forego surgery and decisions by the surgeon to change the type of procedure. The algorithm incorporates the urgency of surgery, clinical risk factors, and functional status. For patients with risk factors, who are undergoing vascular surgery, the studies demonstrate no difference in outcomes between coronary revascularization before noncardiac surgery and proceeding directly to the noncardiac surgery, incorporating heart rate control perioperatively. The class of recommendation and strength of evidence, based on the ACCF/AHA criteria, is shown on the algorithm.

Figure 56-1 Algorithm from the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) for the decision for preoperative cardiovascular testing in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. (Modified from Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al: 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 54:e13-e118, 2009.) HR, Heart rate; LOE, level of evidence; MET, metabolic equivalent.

8. What is the value of coronary revascularization before noncardiac surgery?

9. What is the concern regarding surgery in patients with a previous PCI?

Patients who have previously undergone PCI have not been shown to have a significant difference in perioperative outcomes compared with case-matched controls. Importantly, the risk of thrombosis after PCI is high and the hypercoagulable perioperative state increases the probability of this occurring. Multiple cohort studies and case reports have reported the occurrence of acute thrombosis and perioperative MI at the site of coronary stents. In patients with bare metal stents, this most commonly occurs in patients who have undergone noncardiac surgery within 30 days. In patients with drug-eluting stents, the higher rate of acute thrombosis can be seen for at least 1 year, and there are data to suggest it continues after this period. Therefore, the current recommendation is to delay elective surgery for at least 14 days after balloon angioplasty (without stenting), at least 30 days after placement of bare metal stents, and until 1 year after placement of drug-eluting stents.

10. How should antiplatelet agents be managed in the perioperative period?

11. How should beta-adrenergic blocking agents (β-blockers) be managed in the perioperative period?

12. How should statins be managed in the perioperative period?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Devereaux, P.J., Xavier, D., Pogue, J., et al. Characteristics and short-term prognosis of perioperative myocardial infarction in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:523–528.

2. Devereaux, P.J., Yang, H., Yusuf, S., et al. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1839–1847.

3. Fleisher, L.A., Beckman, J.A., Brown, K.A., et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:e13–e118.

4. McFalls, E.O., Ward, H.B., Moritz, T.E., et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2795–2804.

5. Poldermans, D., Bax, J.J., Boersma, E., et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery: the Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2769–2812.

6. Poldermans, D., Bax, J.J., Schouten, O., et al. Should major vascular surgery be delayed because of preoperative cardiac testing in intermediate-risk patients receiving beta-blocker therapy with tight heart rate control? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:964–969.

7. Poldermans, D., Boersma, E., Bax, J.J., et al. The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mortality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergoing vascular surgery. Dutch Echocardiographic Cardiac Risk Evaluation Applying Stress Echocardiography Study Group [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1789–1794.