Prenatal, Congenital, and Neonatal Abnormalities

Imaging Modalities

Ultrasonography

Color Doppler provides valuable characterization of a lesion’s vascularity and blood supply, detects possible arteriovenous shunting, and depicts the major neck vessels. Three-dimensional reconstruction clearly depicts the relationship of cervical lesions with adjacent facial and skull base structures (e-Fig. 14-1). Potential shortcomings of ultrasonography involve cases with poor acoustic windows because of an anterior position of the placenta, maternal obesity or polyhydramnios, and abnormal fetal position with unusual flexion and extension of the fetal neck.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Useful MRI sequences for fetal neck imaging include the following:

1. Ultrafast spin echo T2-weighted sequences are excellent for imaging of normal anatomical structures and depiction of cervical lesions.

2. Spoiled gradient echo T1-weighted imaging is helpful for imaging of the thyroid gland and blood flow within the major cervical vessels, as well as for depiction of intralesional blood products and calcifications.

3. Gradient echo planar imaging is helpful for detection of blood products, calcifications, and bony details.

4. Steady state or balanced gradient echo sequences are valuable in the prenatal assessment of preservation or impairment of swallowing in the fetus (Video 14-1). The details of fetal airway compromise secondary to the presence of a cervical mass should always be carefully examined.

MRI sequences for imaging of neonatal neck lesions include the following:

1. High resolution 2- to 3-mm T1- and T2-weighted and postcontrast imaging with fat-suppression in orthogonal planes

2. Ultrafast spin echo imaging for optimal visualization of thin fluid–filled sinus tract or fistula

3. Diffusion-weighted imaging, which is particularly useful for identification of hypercellular tumors and infected cystic lesions with viscous, purulent content

4. Magnetic resonance angiography, which may provide crucial information regarding vascular anatomy

Vascular Tumors

Infantile Hemangioma

On cross-sectional imaging, it appears as a lobulated mass with intense uniform enhancement, which usually demonstrates intralesional flow voids on MRI (Fig. 14-2, A). Proliferation may be biphasic. Careful assessment of upper airway status is important because the deep portions of a cervical hemangioma may enlarge sufficiently at this stage to impinge on the airway and cause obstruction. During the final involution phase, which may continue for up to 12 years, the rate of regression is variable. Involution is never complete, although the residual lesion may not be grossly visible; in the neck, it leaves persistent fibrofatty tissue. Infantile hemangiomas are positive for the glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) marker at all stages of lesion development.

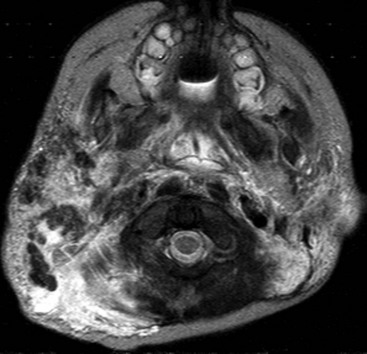

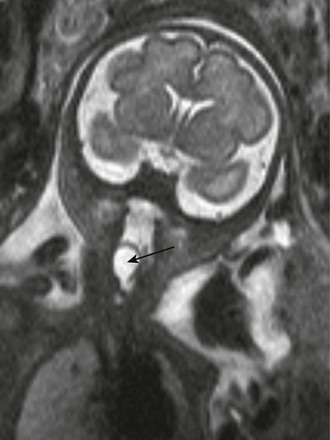

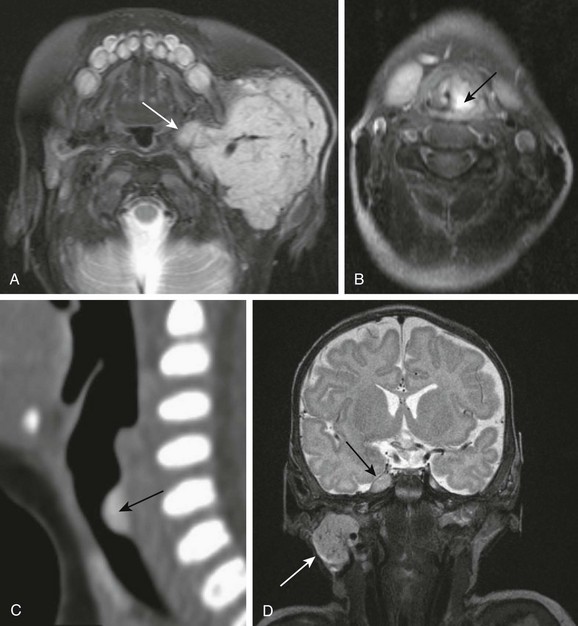

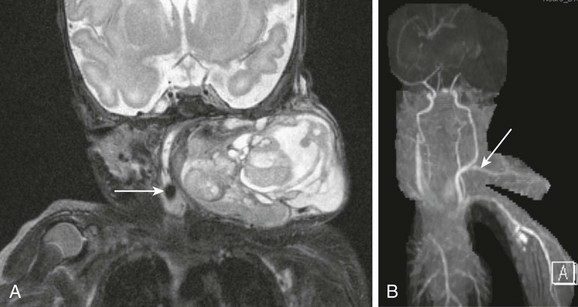

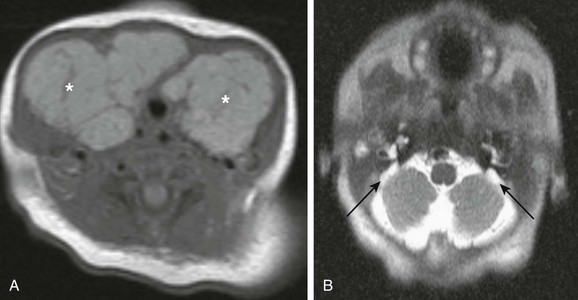

Figure 14-2 Infantile hemangiomas.

A, Parotid infantile hemangioma. A T2-weighted axial image with fat suppression shows a well-circumscribed lobular soft tissue mass in the left parotid with intrinsic flow voids and deep extension into the ipsilateral parapharyngeal space (arrow). The upper airways remain patent. B and C, Upper airways infantile hemangiomas. A T2-weighted axial image with fat suppression shows a small hyperintense hemangioma in the left vocal cord (black arrow), causing severe airway effacement (B). A sagittal reconstructed computed tomography image shows a small lobulated enhancing subglottic hemangioma (black arrow) (C). D, Multifocal infantile hemangiomas with intracranial lesions. A T2-weighted coronal image with fat suppression shows cervical (white arrow) and Meckel cave (black arrow) hemangiomas. (C, Courtesy Avrum N. Pollock, MD.)

Upper airway hemangiomas (see Fig. 14-2, B and C) become symptomatic in the proliferative phase, causing biphasic stridor, respiratory distress, and potentially even life-threatening airway obstruction, which may require emergent intubation. These hemangiomas are often multifocal and occur above and below the vocal cords. Close monitoring with cross-sectional imaging may be indicated because laryngoscopy may not accurately depict the degree of invasion. MRI is preferred in the setting of intubation or tracheostomy.

In rare cases, cervicofacial infantile hemangioma may be associated with central nervous system hemangiomas in intracranial (see Fig. 14-2, D) or intraspinal locations. The reported cases of central nervous system hemangiomas indicate a specific pattern of distribution, with a predilection for the basal cisterns, ventricular system, and extradural spinal involvement.

Congenital Hemangioma

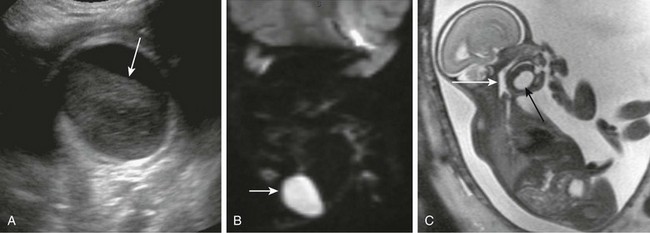

RICH has a predilection for scalp and neck locations. On prenatal imaging, it may appear as a large heterogeneous mass, emanating from the posterior neck (Fig. 14-3, A) with increased vascularity, best demonstrated on obstetric Doppler ultrasonography. Postnatal imaging features of RICH include large irregular flow voids and arterial aneurysms, direct arteriovenous shunts (seen on angiography), and calcifications. Their imaging appearance may occasionally resemble congenital infantile fibrosarcoma.

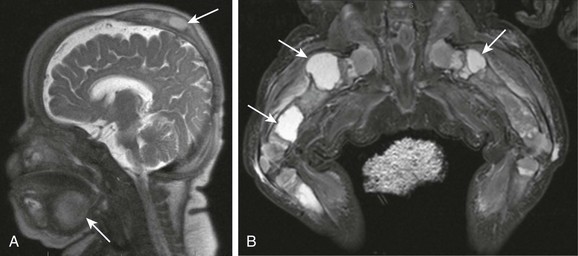

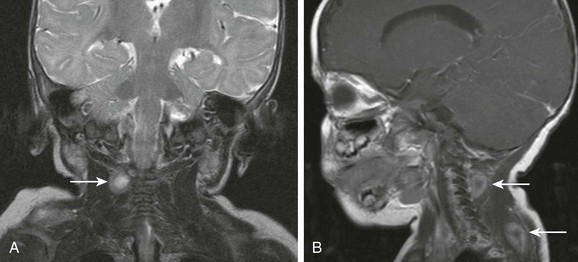

Figure 14-3 Congenital hemangiomas.

A, A fetal magnetic resonance imaging, sagittal half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo image shows a complex soft tissue mass in the posterior neck (black arrow) with internal hypointensity, indicative of blood products. B, A sagittal magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted image of a 1-day-old newborn’s neck shows a very large heterogeneous mass with internal flow voids in the posterior neck. Enlargement of ipsilateral carotid artery (white arrow) and cardiomegaly indicate high-output congestive heart failure.

RICH may have a dramatic presentation at birth with high-output congestive heart failure, which may occur in the setting of a large hemangioma (see Fig. 14-3, B). Rapid involution is usually completed by 14 months of age. Usually, RICH is managed conservatively. Presence of complications may prompt surgical removal.

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma

KHE is a rare, aggressive vascular tumor of infancy of intermediate malignancy and differs from hemangioma by histopathology and clinical appearance. The head and neck are uncommon locations. KHE presents as an ill-defined vascular mass with stranding in the subcutaneous fat, intralesional calcifications, and prominent feeding and draining vessels (e-Fig. 14-4). It tends to cause bony destruction and may be associated with the Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. It should be noted that thrombocytopenia occurs with the rarer KHE and not with the more commonly seen infantile hemangioma.

Venolymphatic Malformations Spectrum

Ultrasonography demonstrates translucent nuchal thickening, with no identifiable arterial or venous flow by Doppler. MRI reveals focal edema of the posterior fetal neck (e-Fig. 14-5) and, in severe cases, depicts associated lymphedema, pleural effusions, ascites, and anasarca.

e-Figure 14-5 Fetal magnetic resonance imaging of nuchal cystic hygroma.

A sagittal half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo image of the 19-week-old fetus shows unilocular cystic mass within the posterior fetal neck (arrow) and moderate pleural effusion, compressing the lung.

Lymphatic or venolymphatic malformations of the fetal or neonatal neck represent congenital lesions that may be apparent at birth or may “silently” grow with a child in the first few years before suddenly becoming symptomatic following spontaneous hemorrhage or infection. They usually present as large, transspatial, multicystic masses with intervening septations and fluid–fluid levels (Fig. 14-6, A and B). Ultrasonography demonstrates septated hypoechoic cystic lesions (see Fig. 14-6, C) without internal vascularity, although some vascular flow may be seen within the intralesional septae.

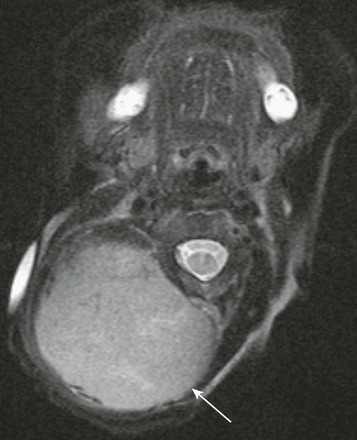

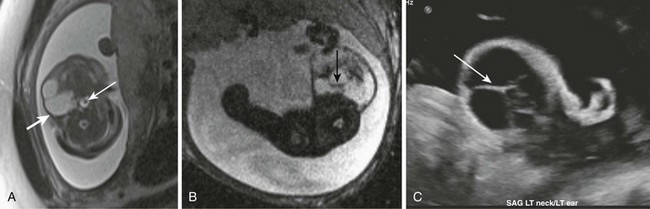

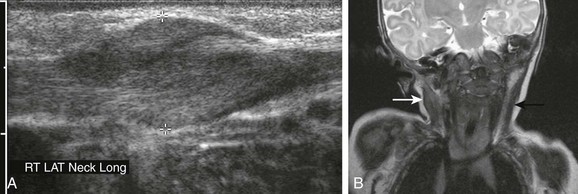

Figure 14-6 Lymphatic malformations.

Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (A, B), fetal ultrasonography (C). Axial half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo (A) and gradient echo planar imaging (B) scans show a multicystic mass of the lateral neck (thick white arrow) with blood-fluid level (black arrow). The airways remain patent (thin white arrow). Fetal ultrasonography (C) shows hypoechoic multicystic lesion with thick intralesional septations (arrow). Hyperechoic debris indicates blood products.

Systemic lymphatic malformations include rare conditions known as lymphangiomatosis and Gorham disease (vanishing bone disease). These entities are poorly understood and likely represent a spectrum of congenital disorders of lymphatic development. They manifest by numerous foci of vascular and lymphatic proliferation, involving multiple organs, including bones and lungs (Fig. 14-7 and e-Fig. 14-8), and often cause serious consequences.

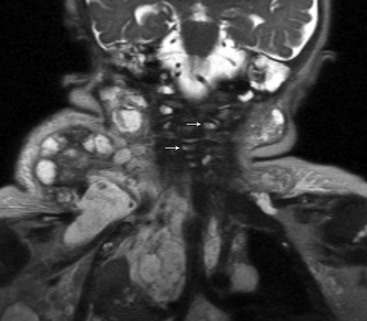

Figure 14-7 Lymphangiomatosis.

A coronal magnetic resonance half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin echo image shows large complex cystic masses in the lateral neck, extending into the thorax, and numerous small cysts (arrows) involving the vertebra.

e-Figure 14-8 Gorham disease (vanishing bone disease).

A sagittal magnetic resonance imaging half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo image through the head (A) and coronal short TI inversion recovery image through the legs (B) show numerous lymphatic malformations (arrows), involving the skull, submandibular neck, and bones and soft tissue of the lower extremities (arrows).

Venous Vascular Malformations

On imaging, they appear as well-defined, ovoid, heterogeneous lesions with strong enhancement and occasional intralesional phleboliths (Fig. 14-9). A calcified phlebolith may occasionally simulate a flow void on MRI, leading to an erroneous identification of the lesion as a hemangioma. Many lesions may be successfully treated with sclerotherapy, although larger and infiltrative lesions may be more challenging to treat.

Figure 14-9 Venovascular malformation.

A T2-weighted fat-suppressed image shows an ovoid heterogeneous lesion, almost replacing the tongue with numerous hypointense phleboliths.

Teratoma

Teratomas are subdivided into mature, immature, and malignant types, each of which differs by histology and hence imaging appearance. Benign mature lesions are mostly cystic, whereas immature lesions tend to be more solid. Malignant teratoma types are uncommonly found in the neck and are less aggressive compared with other locations. Most teratomas demonstrate a combination of cystic and solid components (Fig. 14-10, A to C). Intratumoral foci of hemorrhage and necrosis are suggestive of malignancy. Intralesional fat and calcifications are nearly pathognomonic findings for teratoma but may not always be discernible on fetal MRI and are better seen on ultrasonography. Cervical teratoma and congenital hemangioma share many MRI and ultrasonography features, including interval growth in utero, and establishing the correct diagnosis may be quite challenging. Both imaging modalities are often necessary for optimal assessment.

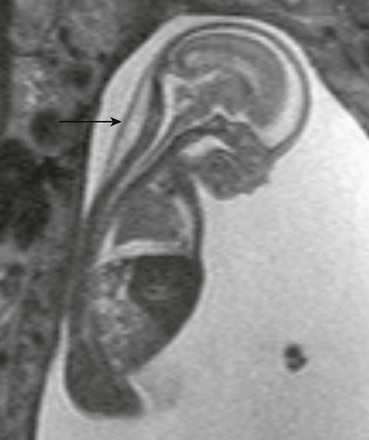

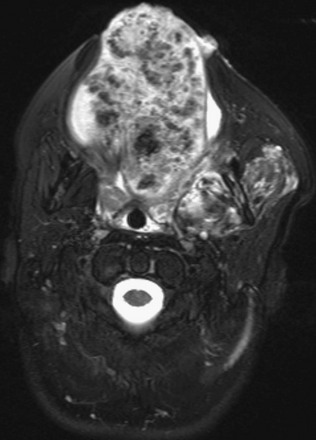

Figure 14-10 Fetal cervical teratomas.

A, A fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), sagittal half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) image shows predominantly cystic teratoma (large arrow) with small solid component in the anterolateral neck. Upper airways are distended, but motion of soft palate (small arrow) is preserved. B, A fetal MRI coronal HASTE image shows a complex cervical teratoma with mixture of cystic (white arrow) and solid (black arrow) components. C, A fetal MRI shows mainly solid lesion with small cystic components, extending from the skull base to the upper chest, which appears to encroach the airway. The lesion proved to be a malignant, immature teratoma.

Postnatal imaging of teratomas may include CT, which is helpful for demonstration of osseous involvement. MRI, with or without contrast, is superb for precise depiction of lesion morphology and extension (Fig. 14-11, A). Magnetic resonance angiography may provide crucial information about the vascular supply for surgical planning (see Fig. 14-11, B). Surgical treatment of teratomas may be curative, although the mortality rate remains high. Persistent disfiguration of facial structure, voice issues, and hypothyroidism are among the common complications.

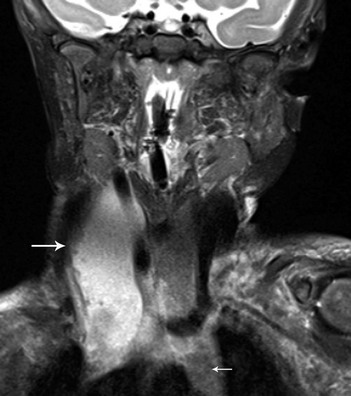

Figure 14-11 Neonatal cervical teratoma.

A, A coronal T2-weighted image with fat suppression shows a very large complex teratoma of the lateral neck with cystic and solid components, internal flow voids, causing severe compression of airways. Endotracheal tube is evident (arrow). B, Neck magnetic resonance angiography shows a large arterial feeder (arrow), originating from the carotid artery, and providing blood supply to the tumor.

Cervical Cystic Lesions

Dermoid and Epidermoid Cysts

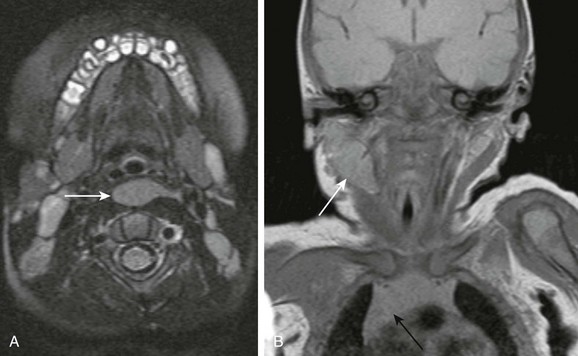

Epidermoid cysts are rare congenital unilocular lesions, which may closely resemble a thyroglossal duct cyst; however, a characteristic pattern of restricted diffusion typical for epidermoids helps distinguish these entities. Epidermoid cysts appear earlier, compared with dermoid cysts, with most lesions being evident during infancy (Fig. 14-12, A and B) or diagnosed prenatally (see Fig. 14-12, C). Dermoids and epidermoids have different histologies, but it is not always possible to differentiate them on imaging. It is more important to define the lesion position in relation to the oral floor muscles, as it may guide a surgical approach.

Figure 14-12 Cervical epidermoids.

A, Submandibular unilocular cystic structure with hyperechoic content on ultrasonography and fluid level (arrow). B, Restricted diffusion pattern on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diffusion-weighted image. C, Fetal sagittal MRI shows unilocular submandibular epidermoid (black arrow). Airways are patent; hypopharynx is distended (white arrow).

Laryngocele

Clinically, laryngoceles may manifest as fluctuating soft tissue masses causing airway obstruction in young infants, or the masses may be diagnosed prenatally (e-Fig. 14-13). Evaluation of a laryngocele with high-resolution cross-sectional imaging depicts the anatomic boundaries of the lesion and the contents of the cyst, which may be filled with air, fluid, or proteinaceous material.

Foregut Duplication Cyst

Foregut duplication cysts in the neck may be incidental findings, may present in the neonate with frank respiratory distress secondary to obstruction, or may be diagnosed prenatally as unilocular cystic masses in the anterior compartment of the fetal neck and mediastinum (e-Fig. 14-14). The cyst may or may not communicate with the esophagus; however, thorough search for this communication should be performed. Identification of abnormal canalization of the gastrointestinal tract confirms the diagnosis of foregut duplication cyst.

e-Figure 14-14 Fetal esophageal duplication cyst.

A fetal coronal half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo image shows a large unilocular cystic structure in the fetal anterolateral neck (large white arrow), which continues into superior mediastinum. Fetal airways appear patent (small white arrow).

Cervical Soft Tissue Masses

Ectopic thymus is usually discovered incidentally on neck imaging performed for unrelated indications. It may be seen anywhere along the course of the primordial thymopharyngeal duct, from the mandibular angle to the thoracic inlet. It is located most often along the carotid sheath but may extend to the midline (Fig. 14-16, A) or may be bilateral. It may be recognized by its imaging characteristics, identical to orthotopic thymus (see Fig. 14-16, B). Ectopic thymus usually resolves with involution of the intrathoracic orthotopic thymus.

Figure 14-16 Ectopic thymus.

A, An axial magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted image shows unusual retropharyngeal location of ectopic thymus (arrow). B, Ectopic thymus (white arrow) in the right lateral neck of a 1-week-old infant has signal characteristics similar to the visualized orthotopic thymus (black arrow). The lesion elicits no significant mass effect. The airways are patent.

Fetal or Neonatal Goiter

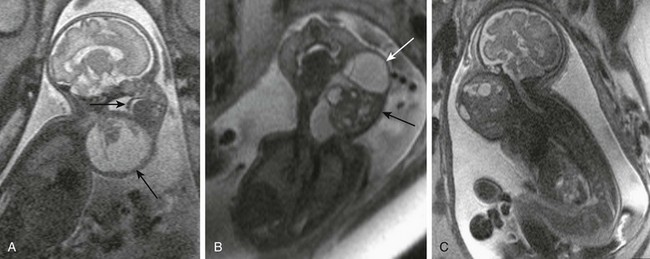

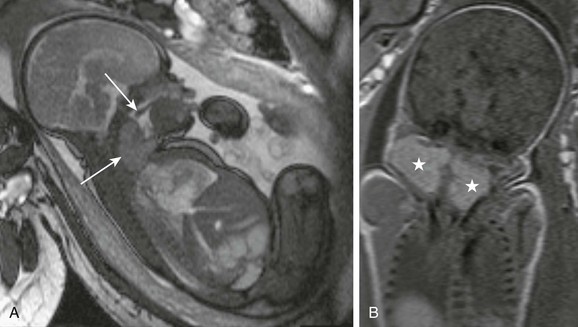

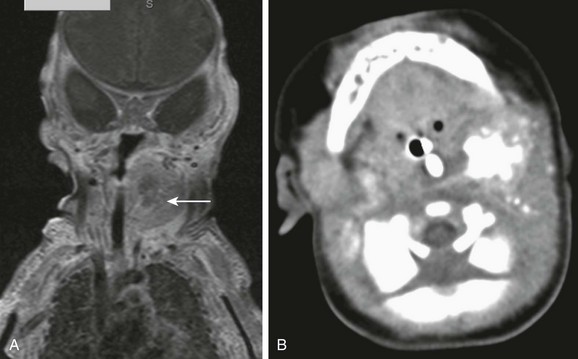

Fetal goiter may be diagnosed on ultrasonography as a bilobed echogenic mass in the anterior neck, with increased vascularity; fetal MRI demonstrates a midline symmetric cervical mass with high signal on T1-weighted imaging (Fig. 14-17). Treatment of fetal goiter includes intra-amniotic thyroxin injection, the main goal being reduction in the size of the goiter and prevention of tracheal obstruction. It may be associated with congenital deafness in the setting of Pendred syndrome (e-Fig. 14-18).

Figure 14-17 Fetal goiter.

A, A fetal magnetic resonance imaging sagittal true fast imaging with steady precession image shows a homogeneous cervical mass (bottom arrow), causing mild distension of hypopharynx. Free motion of soft palate (top arrow) remains preserved. B, A coronal T1-weighted image shows the bilobed uniformly T1-hyperintense lesion (stars), indicative of the iodine content of thyroid gland.

e-Figure 14-18 Pendred syndrome.

A, An axial T1-weighted image through the neck shows large symmetric enlargement of thyroid lobes and isthmus (asterisks), which causes almost complete encasement of the trachea. B, An axial half Fourier acquisition single shot turbo spin echo image through the skull base in the same patient shows bilateral enlargement of vestibular aqueducts (black arrows). The findings of thyroid goiter and congenital deafness are indicative of Pendred syndrome.

Infantile Fibromatoses

Infantile fibromatosis represents a spectrum of rare congenital disorder that involves skeletal and smooth muscles in very young children. It may manifest as a solitary form or as a multicentric form with visceral involvement. Aggressive infantile fibromatosis occurs in the first 2 years of life and may present as a nodular soft tissue mass in the head and neck, with an imaging appearance mimicking infantile fibrosarcoma or hemangioma. A desmoid type of fibromatosis may present as a nodular tumor, which often grows along the nerve sheath or vascular bundle and has a tendency to frequent hemorrhage or necrosis in the central portion, producing a target appearance on imaging (Fig. 14-19). The prognosis is good for solitary neck lesion. These lesions usually stop growing or spontaneously regress.

Figure 14-19 Infantile fibromatosis.

Coronal T2-weighted (A) and sagittal postcontrast (B) magnetic resonance imaging scans show multiple scattered nodular masses (arrows) of the neonatal neck with typical “target” appearance of desmoids type of infantile fibromatosis.

Fibromatosis colli is a benign condition that involves the sternocleidomastoid muscle only. It usually affects neonates and manifests as a hard unilateral soft tissue mass associated with ipsilateral torticollis caused by the muscular contraction and rotation of the chin to the opposite side. Imaging, with ultrasonography or MRI, may be performed if the clinical presentation is unusual. Both modalities reveal diffuse or focal enlargement of sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 14-20) and no discrete mass or lymphadenopathy. Congenital torticollis usually spontaneously resolves in a few months. A child with cervical lymphadenitis and retropharyngeal abscess may present with a postinflammatory torticollis known as Grisel syndrome; this condition is caused by increased ligamentous laxity.

Figure 14-20 Fibromatosis colli.

A, Ultrasonography of a 5-week-old male infant shows fusiform enlargement of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (cursors). B, A coronal T2-weighted image in another patient shows diffuse thickening and hyperintensity of right sternocleidomastoid muscle (white arrow), associated with ipsilateral torticollis. The left sternocleidomastoid muscle (black arrow) demonstrates normal thickness and signal intensity. (A, Courtesy Brian D. Coley, MD.)

Neonatal Malignancy

The imaging of cervical neuroblastoma may be performed with CT or MRI (Fig. 14-21). Both modalities may depict tumor extension, presence of mineralization, and bony or spinal canal invasion. Restricted diffusion pattern on diffusion-weighted MRI confirms the hypercellular, malignant nature of the tumor. Intratumoral dystrophic calcifications are not uncommon and are observed in 50% of cervical neuroblastomas.

Figure 14-21 Primary cervical neuroblastoma.

A coronal postcontrast T1-weighted image with fat suppression (A) shows a heterogeneous mass (arrow) within the left neck, along the presumable course of the sympathetic chain with central lack of enhancement, which prove to be chunky internal calcifications on computed tomography (B).

Congenital Infantile Fibrosarcoma

Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma, a rare tumor of infancy, has a markedly different clinical course and a more favorable prognosis compared with adult fibrosarcoma. It may present at birth or soon after or may be diagnosed in utero. Infantile fibrosarcoma has unique cytogenetic findings, which help distinguish this tumor from other infantile tumors such as embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma or from infantile fibromatosis. The tumor appears as a large solid soft tissue mass of the neck (e-Fig. 14-22), which may be rather homogeneous or have central necrosis and hemorrhage.

Berenguer, B, Mulliken, JB, Enjolras, O, et al. Rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma: clinical and histopathologic features. Pediatr Development Pathol. 2003;6:495–510.

Boye, E, Jinin, M, Olsen, BR, et al. Infantile haemangioma: challenges, new insights and therapeutic promise. Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(suppl 1):678–684.

Cahill, AM, Nijs, E, Ballah, D, et al. Percutaneous sclerotherapy in neonatal and infant head and neck lymphatic malformations: a single center experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(11):2083–2095.

Francisca, SM, Kyriaki, A, Karl, OK, et al. Cystic hygromas, nuchal edema, and nuchal translucency at 11–14 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):678–683.

Grassi, R, Farina, R, Floriani, I, et al. Assessment of fetal swallowing with gray-scale and color doppler sonography. AJR. 2005;185(5):1322–1327.

Hubbard, AM, Crombleholme, TM, Adzick, NS. Prenatal MRI evaluation of giant neck masses in preparation for the fetal exit procedure. Am J Perinatol. 1998;15(4):253–257.

Konez, O, Burrows, PE, Mulliken, JB, et al. Angiographic features of rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma (RICH). Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:15–19.

Laje, P, Johnson, MP, Howell, LJ, et al. Ex utero intrapartum treatment in the management of giant cervical teratomas. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(6):1208–1216.

Murphey, MD, Ruble, CM, Tyszko, SM, et al. Musculoskeletal fibromatosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2009;29:2143–2183.

Nath, CA, Oyelese, Y, Yeo, L, et al. Three-dimensional sonography in the evaluation and management of fetal goiter. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(3):312–314.

Restrepo, R, Palani, R. Hemangiomas revisited: the useful, the unusual and the new. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:895–904.

Rossler, L, Rothoeft, T, Teig, N, et al. Ultrasound and color Doppler in infantile subglottic haemangioma. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:1421–1428.

Viswanathan, V, Smith, ER, Mulliken, JB, et al. Infantile hemangiomas involving the neuraxis: clinical and imaging findings. AJNR. 2009;30:1005–1013.