Chapter 23 Premenstrual Syndrome and Menstrual-Related Disorders

INTRODUCTION

The literature on PMS has focused almost entirely on women with adverse premenstrual experiences. Some women experience well-defined medical conditions, such as migraine, epilepsy, irritable bowel syndrome, and asthma, that are linked to, and exacerbated by, the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. However, there is evidence that 5% to 15% of women may experience positive changes in the premenstruum.1 Clinicians now understand the need to discriminate between the usual premenstrual experience of ovulatory women (wherein premenstrual molimina forewarn of impending menstruation) and PMS. This chapter reviews our current understanding of menstrual-related conditions, including PMS.

DEFINITION AND PREVALENCE

Molimina

Molimina are symptoms, such as breast pain, swelling, bloating, acne, and constipation, that foreshadow impending menstruation. Some or all of these symptoms are estimated to occur in 80% to 90% of women of reproductive age. Approximately 30% to 40% of women report these symptoms to be distressing enough that they would seek a remedy if one were available. Swelling of the extremities and abdominal bloating are molimina reported by 60% of women, although objective documentation of weight gain is usually lacking.2,3 Cyclic breast symptoms affect 70% of women, with 22% reporting moderate to extreme discomfort.4

Premenstrual Syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome is defined as the cyclic recurrence in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of a combination of distressing physical, psychological, and/or behavioral changes of sufficient severity to result in deterioration of interpersonal relationships and/or interference with normal activities.5 This definition emphasizes the fact that a diagnosis of PMS should rely not only on the presence of typical premenstrual symptoms, but also on a level of severity enough to disrupt normal function. The term PMS should be reserved for a more severe constellation of symptoms, mostly psychiatric, that leads to major interference with day-to-day activities and interpersonal relationships.6 Women with this degree of symptoms probably comprise 3% to 5% of women in their reproductive years.7–10

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

In the psychiatric literature, the term premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is used to indicate the most serious premenstrual disturbances that are associated with deterioration in functioning. PMDD is characterized by depressed or labile mood, anxiety, irritability, anger, and other symptoms occurring exclusively during the 2 weeks preceding menses. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV), the symptoms must be severe enough to interfere with occupational and social functioning (Table 23-1).11 This sets PMDD apart from the more common PMS, as a severely distressing and disabling condition that requires treatment.

Table 23-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)

| 1. Timing of symptoms |

| Symptoms are present during the last week of the luteal phase, remit within the first few days of menses, and are absent during the week following menses. The symptoms occur during most, if not all, menstrual cycles. |

| 2. Symptoms |

| At least five symptoms are required, including at least one of the first four symptoms: |

Adapted from: American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, D.C. APA, 1994.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PMS-like behavior has been reported both in humans and in nonhuman primates that demonstrate menstrual cyclicity. In the nonhuman primate, zoologists have noted premenstrual changes in behavior and appetite similar to those reported by women with PMS.12,13 The availability of effective contraception since midway through the twentieth century has meant that repeated cycles of pregnancy and lactation were no longer the biological destiny of women in the developed world—and as a direct result the expected number of menstrual cycles in a woman’s lifetime increased from as few as 50 to as many as 500, with a commensurate increase in menstrual cycle-related disorders.

Little is known about the inheritance of PMS. However, there is support for a genetic predisposition. Surveys have found that as many as 70% of daughters of affected mothers were themselves PMS sufferers, whereas 63% of daughters of unaffected mothers were symptom-free.14

Premenstrual syndrome disappears during suppression of the ovarian cycle; for example, during hypothalamic amenorrhea due to excessive physical, or nutritional stress, during lactational amenorrhea, during pregnancy, and after menopause—either natural or induced.15,16 Interestingly, hormone therapy employing sequential progestin sometimes triggers PMS symptoms in susceptible women, whereas continuous combination hormone replacement therapy is not associated with these changes.17,18

DIAGNOSIS

History

Caution is needed in immediately accepting such a typical history as diagnostic of PMS. Researchers have found that many psychiatric conditions worsen premenstrually, a situation referred to as premenstrual magnification. Hence, an individual with an underlying psychiatric disorder may recall and relate the symptoms that were most severe in the premenstrual week, while ignoring the lower level of symptoms that exist throughout the month.19

Prospective Symptom Record

The clinician can have confidence in the diagnosis only by obtaining a prospective symptom record over a 1- to 2-month period. Any calendar used for this purpose must obtain information on four key areas: symptoms, severity, timing in relation to the menstrual cycle, and baseline level of symptoms in the follicular phase (Table 23-2). Information should be sought about stresses related to the woman’s occupation and family life, because these may tend to exacerbate PMS. Past medical and psychiatric diagnoses may be relevant in that a variety of medical and psychiatric disorders may show premenstrual exacerbation.

Table 23-2 Key Elements of a Prospective Symptom Record Used for the Diagnosis of PMS

| 1. | Daily listing of symptoms |

| 2. | Ratings of symptom severity throughout the month |

| 3. | Timing of symptoms in relation to menstruation |

| 4. | Rating of baseline symptom severity during the follicular phase |

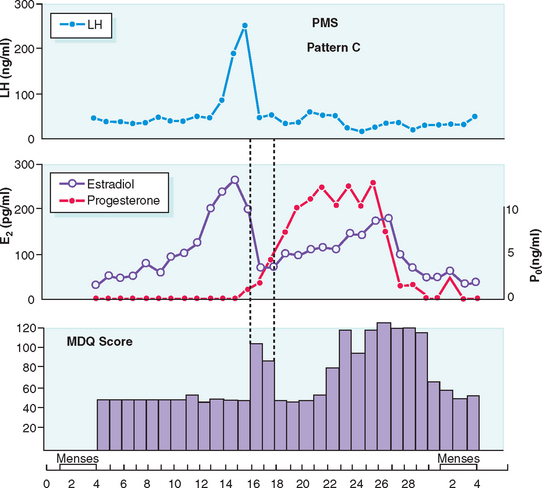

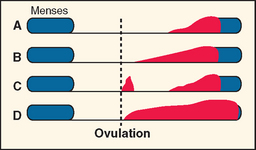

Typically PMS symptoms appear after ovulation and worsen progressively leading up to menstruation. Approximately 5% to 10% of PMS sufferers experience a brief burst of typical PMS symptoms coincident with the midcycle fall in estradiol that accompanies ovulation20 (Fig. 23-1). PMS symptoms resolve at varying rates after onset of menstruation. In some women there is almost immediate relief from psychiatric symptoms with the onset of bleeding; for others the return to normal is more gradual. The most severely affected women report symptoms onset shortly after ovulation (2 weeks before menstruation), resolving at the end of menstruation. Such individuals typically report having only one “good week” per month (Fig. 23-2).21 If this pattern is longstanding it becomes harder and harder for interpersonal relationships to rebound during the good week, with the result that their condition may start to take on the appearance of a chronic mood disorder. Whenever charting leaves the diagnosis in doubt, a 3-month trial of medical ovarian suppression will usually provide a definitive answer.

(From Reid RL: Premenstrual syndrome. In DeGroot L (ed). Endotext.com. Available at: www.endotext.org. Accessed 20 December 2004.)

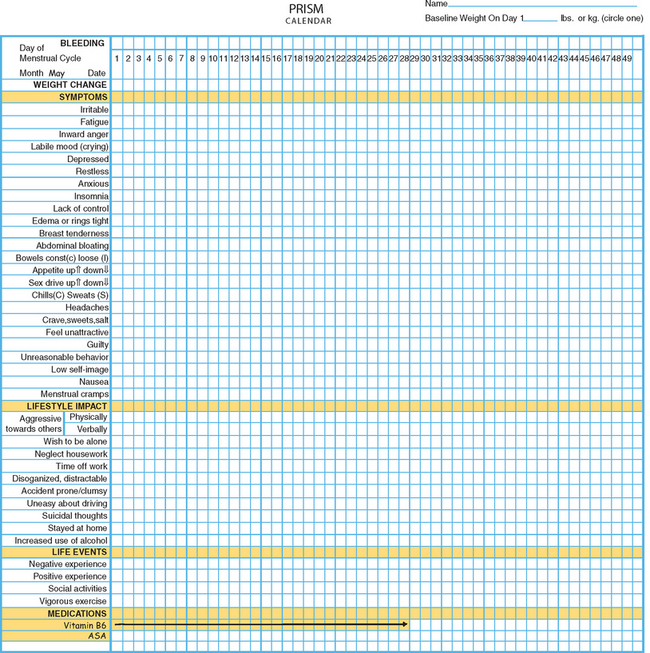

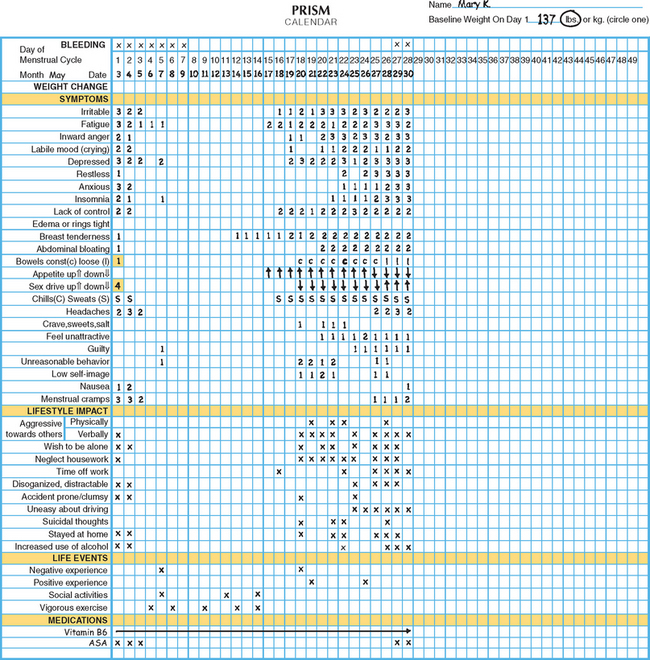

One example of a symptom calendar is the Prospective Record of the Impact and Severity of Menstrual symptoms (PRISM) calendar (Figs. 23-3 and 23-4).5 This instrument allows rapid visual confirmation of the nature, timing, and severity of menstrual cycle-related symptomatology and at the same time provides information on life stressors and current use of PMS therapies.

Figure 23-4 Visual inspection of a completed PRISM calendar reveals a pattern of symptoms consistent with PMS.

Positive premenstrual changes associated with enhanced mood or performance are reported by up to 15% of women. Increased energy, excitement, and well-being have been associated with increased activity, heightened sexuality, and improved performance on certain types of tasks during the premenstrual phase.1

Physical Examination

Organic causes of PMS-like symptoms must be ruled out. Marked fatigue may result from anemia, leukemia, hypothyroidism, or diuretic-induced potassium deficiency. Headaches may be due to intracranial lesions. Women attending PMS clinics have been found to have brain tumors, anemia, leukemia, thyroid dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, pelvic tumors including endometriosis, and other recurrent premenstrual phenomena, such as arthritis, asthma, epilepsy, and pneumothorax.16

ETIOLOGY

Since the 1950s a wide range of etiologic theories have been advanced to explain the varied manifestations of PMS. PMS has been attributed to altered levels or ratios of estrogen and progesterone, androgen excess, fluid retention, endogenous hormone allergy, vitamin and trace element deficiencies, prolactin excess, hypoglycemia, bacterial and yeast infections, thyroid dysfunction, endogenous opiate addiction and withdrawal, abnormal metabolism of essential fatty acids leading to prostaglandin E1 deficiency, and altered calcium metabolism, to mention a few.15

As with other areas of confusion and uncertainty, the area of PMS is an attractive one for those promoting unorthodox treatments for personal gain. Many of the theories that underlie such interventions lack biologic plausibility and appear to have emerged as a means to market specific therapeutic products. Conscientious investigators have expended much effort to rigorously evaluate the promotional claims of others. Randomized, controlled trials have failed to confirm the efficacy of most of these purported treatments.

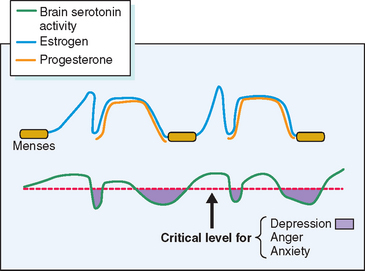

Other theories, while having some biologic plausibility, have not or cannot be confirmed with available diagnostic techniques. No one theory has gained universal acceptance, although consensus is developing that in some susceptible women normal swings in gonadal hormones22 appear to mediate changes in the activity of central neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which in turn incite profound changes in mood and behavior.23 Others have speculated a role for steroid-induced modulation of γ-aminobutyric acid receptors in the brain.24 Although it is likely that many of the physical symptoms (breast tenderness, bloating, constipation) are the direct effect of gonadal steroids, it is intriguing that treatment of PMS with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) will ameliorate the severity of not only psychological, but also physical complaints.25

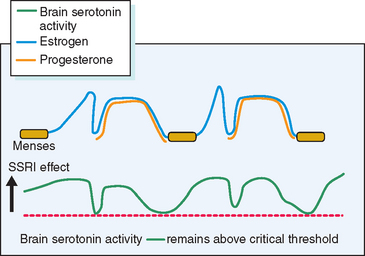

Several lines of evidence from clinical medicine support this interrelationship between estrogen or lack of estrogen effect (perhaps mediated by progestin-induced depletion of estrogen receptors) and central serotonergic activity.23 Estrogen has been shown to alleviate clinical depression in hypoestrogenic women in double-blind clinical trials.26,27 The addition of sequential progestin therapy to estrogen replacement triggers characteristic PMS-like mood disturbance in some susceptible postmenopausal women.17 Anti-estrogens given for ovulation induction may, at times, provoke profound mood disruption. Women with PMS show a surprisingly high frequency of premenstrual and menstrual hot flashes (85% of PMS sufferers vs. 15% of non-PMS controls) that are typical of those experienced by menopausal women.28,29 SSRIs have been shown to relieve hot flashes in breast cancer survivors made menopausal by chemotherapy.30 In each of these circumstances a decrease in exposure to estrogen has been linked to mood disturbance and in each case a decrease in serotonin activity (inferred from the response to SSRIs) appears to be the proximate cause (Fig. 23-5).

THERAPY

Lifestyle Modification Strategies

Diet

There is a paucity of evidence to support a dietary approach to the control of PMS,31 although there are a few simple dietary measures that may afford a measure of relief for the afflicted woman. Most women with PMS, despite feelings of bloating and tension, show no absolute increase in weight, no change in girth, and no signs of peripheral edema.3 PMS sufferers commonly report cravings for salty and sweet foods, and these dietary alterations may account for unusual cases of premenstrual edema.32 Sudden shifts from low-sodium, low-carbohydrate intake to a diet high in these constituents can account for weight gain of as much as 5 kg in 24 hours.33 For this reason reduction in the intake of salt and refined carbohydrates may help prevent edema and swelling in occasional women with this manifestation of PMS.

Although a link between methylxanthine intake and premenstrual breast pain has been suggested, available data are not convincing.34,35 Nevertheless, a reduction in the intake of caffeine may prove useful in women in whom tension, anxiety, and insomnia predominate.

Several lines of evidence indicate that there is a tendency to increased alcohol intake premenstrually,36 and women should be cautioned that excessive use of alcohol is frequently an antecedent factor in marital discord. Anecdotal evidence suggests that small, more frequent meals may occasionally alleviate mood swings. Based on recent evidence that cellular uptake of glucose may be impaired premenstrually, there is at least some theoretical basis for this dietary recommendation.37 Carbohydrates may exhibit mood-altering effects through a number of mechanisms,38 yet attempts to improve premenstrual symptoms through dietary supplements have not been successful.39,40 Calcium supplementation has been shown to be marginally superior to placebo in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial.41

Exercise

Regular aerobic exercise may relieve PMS symptoms, at least temporarily, in many women,42,43 and it should be recommended as part of an overall program of lifestyle modification. Some women with PMS report that exercise is an outlet for the inward anger and aggression that characterizes their symptomatology.

Medical Interventions

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Mefenamic acid (500 mg three times daily) in the premenstrual and menstrual weeks has outperformed placebo for the treatment of PMS in some but not all clinical trials.44,45 Mefenamic acid is contraindicated in women with known sensitivity to aspirin or those at risk for peptic ulcers.

Oral Contraceptives

The first systematic studies to examine the effects of oral contraceptives on PMS did not find differences in PMS symptoms between oral contraceptive users and nonusers, nor were there significant differences between agents with differing progestational potencies.46,47 Monophasic and triphasic preparations showed similar rates of symptomatology.48

A new oral contraceptive preparation containing a novel progestin with diuretic effects (drospirenone) has undergone the most rigorous testing in normal women and women with strictly defined PMDD. The dosage of progestin in each pill is said to be the equivalent to 25mg of spironolactone. Alhough the evidence supporting a role for fluid retention as an etiologic component of PMS is lacking,3 many women are distressed by feelings of bloating and edema. In controlled clinical trials this new oral contraceptive has been shown to offer relief to some physical and some psychological manifestations of PMS with an improvement in health-related quality of life.49,50

Pyridoxine

Published data in regard to the efficacy of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) have been contradictory51; however, this medication in proper dosages (100 mg daily) is, at worst, a safe placebo that becomes one part of an overall management plan for women with distressing molimina that should include lifestyle modification and changes in diet. Patients should be cautioned that these medications do not work for all women and that increasing the dose of pyridoxine in an effort to achieve complete relief of symptoms may lead to peripheral neuropathy. Pyridoxine should be discontinued if there is evidence of tingling or numbness of the extremities.

Diuretics

The routine use of diuretics in the treatment of PMS should be abandoned. Most women show only random weight fluctuations during the menstrual cycle despite the common sensation of bloating. Spironolactone has been reported to alleviate symptoms in some PMS sufferers.52

Anxiolytics

Some women report overriding symptoms of anxiety and tension or insomnia in the premenstrual week.53 New short-acting anxiolytics or hypnotics such as alprazolam (0.25mg twice daily) or triazolam (0.25mg at bedtime), respectively, may be prescribed sparingly for such individuals.54,55 Buspirone has also proven useful for anxiety and may be particularly helpful in circumstances where SSRIs evoke sexual dysfunction.56

Antidepressant Therapy

A range of newer antidepressant medications that augment central serotonin activity have been shown to alleviate severe PMS.57,58 Because these agents will also relieve endogenous depression, a pretreatment diagnosis achieved by prospective charting is very important. For patients in whom psychiatric symptoms predominate, antidepressant therapy may provide excellent results (Fig. 23-6). SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and velafaxine (a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), have all been successfully employed.

Figure 23-6 Hypothetical depiction of how drugs that elevate serotonin activity can alleviate PMS.

(From Reid RL: Premenstrual syndrome. In DeGroot L (ed). Endotext.com. Available at: www.endotext.org. Accessed 1 January 2005.)

Most PMS sufferers would prefer to medicate themselves only during the symptomatic phase of the menstrual cycle. Recent studies have demonstrated that luteal phase therapy may be effective for many women with PMS.59 Practically speaking, a trial of SSRI therapy should be commenced with continuous use. After a woman has determined the optimal response that can be achieved with continuous therapy, it is reasonable for her to try luteal phase-only therapy to determine if the benefit is maintained.

Unfortunately, several follow-up studies have demonstrated the rapid recurrence of severe PMS attended by significant social disruption after cessation of therapy with SSRIs.60,61 Practically speaking this would mean that if this line of therapy is chosen extended treatment may be required.

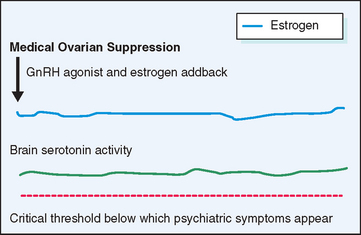

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists

A different approach to the management of severe PMS has been to suppress the ovarian cycle, which is thought to incite the changes in central neurotransmitters that underlie the manifestations of PMS (Fig. 23-7). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists effect rapid medical ovarian suppression, thereby inducing a pseudomenopause and affording relief from PMS.62 This approach is unsatisfactory in the long term not only because of the troublesome menopausal symptoms it evokes, but also because it creates an increased risk for osteoporosis and possibly ischemic heart disease. When combined with hormone replacement therapy GnRH agonists afford excellent relief from premenstrual symptoms without the attendant risks and symptoms resulting from premature menopause. The major drawback to this therapeutic approach is the expense of medication and the need for the patient to take multiple medications on a long-term basis.

Medical Management of Specific Symptoms

Premenstrual Mastalgia

Premenstrual mastalgia, which affects up to 70% of women in reproductive age, may occur in isolation from other PMS symptoms and, as such, should be considered a moliminal symptom. Low doses of danazol, the synthetic analog of ethinyltestosterone, can bring about dramatic relief of mastalgia in most women.66 This medication is given at a dose of 100mg daily for several cycles followed by maintenance doses of 50mg daily in the luteal phase only. Higher doses of danazol (400mg daily) may be required to relieve other PMS symptoms.67 Mastalgia may also respond to tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, at a dose of 10mg daily.68 Diuretics, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and pyridoxine have not been shown to help mastalgia.

Surgical Therapy

Medical approaches to PMS should be exhausted before consideration of surgery (hysterectomy and oophorectomy) for debilitating PMS. Observational trials have shown this therapy to be effective.69,70 For the woman in whom there is unequivocal documentation that premenstrual symptoms are severe and disruptive to lifestyle and relationships and in whom conservative medical therapies have failed (either due to lack of response, intolerable side effects, or prohibitive cost), the effect of medical ovarian suppression should be tested. At times this therapy (a GnRH agonist and continuous combination hormone replacement therapy) can be maintained until menopause with satisfactory symptom control. Some women, despite complete relief of symptoms, cannot afford to or choose not to take this combination of medications for prolonged intervals (as long as 10 to 15 years from diagnosis until menopause in some cases).

EFFECTS OF THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE ON COMMON MEDICAL CONDITIONS

Menstrual Migraine

There is compelling evidence supporting a relationship between reproductive hormones, particularly estrogen, and migraine headache. Table 23-3 gives an overview of mechanisms and management of menstrual cycle-related effects on common medical conditions.

Table 23-3 Mechanisms and Management of Menstrual Cycle-related Effects on Common Medical Conditions

| Medical Condition | Mechanism | Management |

|---|---|---|

OC, oral contraceptive; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone

Migraine and Other Hormonal Events

Migraine headaches are two to three times more common in women than men,71 and their frequency increases considerably after menarche.72 Although 60% of migrainous women link attacks to menstruation,71 only 7% to 14% of women have true menstrual migraine. These women experience migraine headaches, usually without aura, almost exclusively during menses (generally day 1 ± 2 days)73,74 and are virtually free of migraines at other times of the cycle, with the exception of a small percentage of women who experience a brief exacerbation associated with ovulation.71,72

Approximately 70% of women who experience menstrual migraine will improve during pregnancy, especially the second and third trimesters.74,75 These women may experience migraine in the postpartum period, associated with falling estrogen levels.76 Menopause and the climacteric, a time of declining estrogen levels, have a variable effect on migraine, although most women do show a decline in frequency of migraine after menopause.74,77 Oral contraceptives have variable effects on migraine frequency. Similar to menstrual migraine, some oral contraceptive users experience headaches only during the pill-free or placebo days.74,78

Role of Sex Steroids in Headache

Migraines are vascular headaches, associated with a vasoconstrictive phase followed by vasodilatation.79 Estrogen withdrawal is likely responsible for initiating some or all of these vascular effects on intracranial vessels.72,80 Estrogen affects headache by altering neurovascular activity in the brain. Exposure to migraine “triggers” in susceptible patients results in intracerebral release of serotonin, which stimulates dilation of intracerebral vessels. Vessel dilatation activates perivascular neurons, which in turn activate the trigeminal nucleus that results in headache pain. Peripheral serotonin levels affect a patient’s susceptibility to migraine triggers. High estrogen levels are associated with high peripheral serotonin levels, which reduce headache susceptibility. Conversely, when estrogen levels fall, as occurs with menses, ovulation, and postpartum, peripheral serotonin levels also decrease, increasing headache susceptibility and frequency.71,81 Cycling of estrogen levels and prepriming with high levels of estrogen is required for declining estrogen levels to modify peripheral serotonin levels and headache activity.74

In women with menstrual migraine, the onset of headache appears to be triggered by an abrupt decline in serum estrogen levels, rather than by any absolute level. Estrogen administration can preclude the expected migraine attack until the estrogen is discontinued.80,82–84 Progesterone administration, while delaying menstrual flow, does not prevent the occurrence of migraine at the expected time.80

Treatment of Menstrual Migraine

Effective treatment of menstrual migraine depends first on accurate diagnosis of migraine and on establishing a link between attacks and menstruation. This is best accomplished by prospective recording of migraine attacks and menstrual periods by the patient herself for at least 3 months. During this time, symptomatic relief of acute migraine attacks with the usual migraine therapies (ergotamine, analgesics, anti-inflammatory medications, antiemetics) can be offered. NSAIDs can also be used prophylactically, starting 2 days before menses and continuing for 4 to 6 days.85 These are particularly useful if the woman also experiences significant dysmenorrhea.74

The development of the triptans, serotonin receptor agonists, has significantly improved the management of migraine headaches.86 These medications selectively activate serotonin receptors on intracranial blood vessels and the trigeminal nerve, causing vasoconstriction of abnormally dilated intracranial vessels and inhibition of neurogenic inflammation.87 Acute attacks of menstrual migraine respond well to sumatriptan. Short-term prophylaxis with sumatriptan (2.5mg three times daily) for 5 consecutive perimenstrual days has also proven effective in treating menstrual migraine,88,89 although the cost-effectiveness and long-term safety of this regimen requires further study.87

Prophylactic hormonal therapy to stabilize estrogen levels is indicated for women with menstrual migraine who do not experience adequate relief from symptomatic treatment.82–84,90,91 Estrogen can be administered either orally or percutaneously as a 50- or 100-μg transdermal patch or 1.5mg of percutaneous estradiol gel.74,92 Percutaneous estrogen may be more effective because there is less variation in serum estrogen levels compared to oral preparations.74 Estrogen should be started in the late luteal phase, at least 48 hours before the anticipated onset of migraine, and should be continued for 4 to 6 days. Estradiol (1mg) taken sublingually immediately at the onset of the headache may interrupt the usual progression to migraine.93

Medications that suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis have been successful for treatment of women whose menstrual migraines are refractory to the usual therapies. The combination oral contraceptive pill can be given continuously for 3 to 4 months, followed by a withdrawal bleed and symptomatic treatment of any resulting migraine attack.91 A new 28-day oral contraceptive that maintains continuous, albeit lower, estrogen administration rather than placebo for the last 7 days is currently being developed and may be very useful for women experiencing menstrual migraine or migraine on the oral contraceptive during the usual pill-free or placebo week.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists are a useful tool for both diagnosis and treatment of menstrual migraine but should be tried only after all other possible treatments have been exhausted. A recent report demonstrated dramatic success in treating menstrual migraine with GnRH agonists, combined with continuous low-dose estrogen replacement therapy.94 Women who respond to this treatment typically can expect to experience long-term relief after surgical oophorectomy with low-dose estrogen replacement therapy. Concomitant hysterectomy, although unnecessary for migraine prevention, simplifies subsequent hormone therapy, if necessary for menopausal symptoms. This “definitive” therapy should only be offered to the woman with recalcitrant menstrual migraine who has completed her childbearing.

Catamenial Epilepsy

The term catamenial is derived from the Greek word Katamenios, which means monthly, because historically the cyclic nature of epileptic attacks was thought to be due to the cycles of the moon.95 Catamenial epilepsy is observed in 10% to 70% of epileptic women.95,96 As in menstrual migraine, the wide range in reported incidence is due to the lack of a generally accepted definition.96 Strictly defined, catamenial epilepsy is epilepsy that occurs at or worsens around menstruation, such that at least 75% of seizures occur over the 10 days beginning 4 days before menses, representing a sixfold increase in daily seizure frequency.95–97 Whereas up to 70% of epileptic women claim that their seizures are exacerbated by menstruation,96 true catamenial epilepsy can be objectively demonstrated in approximately 12%.96

Menstrual exacerbations occur with all types of seizures, although they may be more common in women with focal epilepsy rather than generalized seizures.95 Three distinct patterns of catamenial epilepsy have been described in women with ovulatory cycles: perimenstrual, periovulatory, and luteal.98 In the most common, perimenstrual pattern, seizure frequency is greatest during the menstrual phase (day -3 to +3) compared to the midfollicular and midluteal phases. The periovulatory pattern is characterized by increased seizure frequency during the ovulatory (midcycle) phase, compared to the midfollicular and midluteal phases. In the luteal pattern, seizure frequency is greatest in the ovulatory, midluteal, and menstrual phases, compared to the midfollicular phase.

Women with anovulatory cycles tend to experience an overall increase in seizure frequency throughout their cycle, compared to women with ovulatory cycles. This is very likely due to the overall lower progesterone levels that are consistent with anovulation. In contrast to the pattern seen in ovulatory women, seizures are significantly less common during menses compared with the remainder of the cycle in anovulatory women.99

Some women with epilepsy appear to be at increased risk for ovulatory dysfunction. One study identified anovulatory cycles in 35% of women with temporal lobe epilepsy, compared with 8% of controls.100 Other reproductive endocrine disorders, including polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, and premature ovarian failure, appear to have a higher prevalence in women with epilepsy.101,102

Pathophysiology of Catamenial Epilepsy

Catamenial epilepsy is believed to result from cyclic alterations in both ovarian hormone levels and drug metabolism. Seizure threshold is increased by progesterone and decreased by estrogen.103 A decrease in the progesterone level, or in the progesterone to estrogen ratio, correlates with increased seizure activity.104 Seizure frequency has been shown to increase during two specific times in the menstrual cycle. The first corresponds to the rapid decrease in progesterone just prior to menses, and the second to the elevation of estrogen prior to ovulation.103 An increase in seizure frequency has also been demonstrated during anovulatory cycles when progesterone levels are relatively low.105

Altered metabolism of anticonvulsants at different times in the cycle is well established.95,106 The decrease in estrogen and progesterone at menstruation is believed to stimulate the release of hepatic monoxygenase enzymes, which accelerates anticonvulsant metabolism and increases the risk for breakthrough seizures.95,106 Treatment of catamenial epilepsy should include measurement of serum levels of anticonvulsants during times of seizure exacerbation. A supplemental daily dose of seizure medication at the time of exacerbation may improve seizure control.107

Treatment of Catamenial Epilepsy

Accurate prospective documentation of seizures in relation to menstrual periods is essential for diagnosis and before specific treatment. Many investigators have shown progesterone therapy to be beneficial.104,105,108–112 Medroxyprogesterone acetate given orally (10–40mg daily) or intramuscularly (150mg q 6–12 weeks) has been the most widely studied.104,105 In addition to its antiepileptic properties, progesterone given in this fashion may also reduce seizure frequency by suppressing gonadotropin release, which, in turn, lowers estrogen levels.108 More recently, natural micronized progesterone has also proven effective treatment in some women. In one study, eight women with temporal lobe epilepsy were treated with progesterone vaginal suppositories, 50 to 400mg every 12 hours, during the phase of highest seizure frequency. The average monthly seizure frequency declined by 68%, and overall 75% of women had fewer seizures during the 3-month study period.110,111 In another larger study of 36 women treated with sublingual progesterone, focal and generalized seizures were reduced by 68% and 57%, respectively, and 4 patients became seizure-free.113 The effects of combined oral contraceptives on seizure frequency have been inconsistent, with seizure exacerbation occurring on pill-free days in some reports.104 Uninterrupted combination oral contraceptives or the progestin-only oral contraceptive may be preferable in women with epilepsy because they result in continuous progestin exposure.114

There are few studies describing the use of GnRH agonists for the treatment of catamenial epilepsy refractory to other therapies.115,116 Although these drugs are generally effective at reducing seizure frequency, their effects on bone demineralization may preclude long-term use.

Premenstrual Asthma

Up to 40% of women with asthma experience an increased frequency and severity of asthma symptoms premenstrually or at menstruation.117,118 Gibbs and coworkers119 objectively confirmed the worsening of asthmatic symptoms premenstrually by documenting significant decreases in peak expiratory flow rates. There is also some evidence that women are more likely to be hospitalized premenstrually for asthma complications, including respiratory failure.120–122

The precise etiology of premenstrual asthma remains elusive but may be related to changing levels of progesterone or prostaglandins. Progesterone level increases steadily after ovulation and falls abruptly in the days prior to menstruation. Its relaxant effect on smooth muscle contractility may contribute to cyclic changes in airway responsiveness.123 Progesterone-stimulated hyperventilation may further influence asthma, leading to symptomatic deterioration and dyspnea.

A subjective increase in asthma symptoms, along with an objective increase in peak expiratory flow rates, has been demonstrated in women with premenstrual asthma; however, an associated deterioration in airway reactivity has not been shown.124 There is also no relationship between airway function and absolute levels of progesterone. Although some prostaglandins have bronchoconstrictive effects, studies have failed to show any relationship between endogenous prostaglandin synthesis and premenstrual asthma.125 Menstrual cycle-related alterations in immune mechanisms have also been suggested.126 It has been suggested that premenstrual asthma may in part be due to altered perception or heightened awareness of symptoms, perhaps related to PMS.117 An association has been reported between premenstrual asthma and symptom scores for PMS and dysmenorrhea.121

Both estrogen and progesterone can alter β2-adrenoceptor function and regulation, thereby potentiating the brochorelaxant effects of catecholamines. There are cyclic changes in β2-adrenoceptors during the menstrual cycle in normal women, with up-regulation of receptors during the luteal phase, most likely related to progesterone.127 Interestingly, this cyclic change is lost in asthmatic women, who demonstrate a paradoxical down-regulation of receptors when exposed to progesterone.127 The altered β2-adrenoceptor function and regulation may reduce response to both endogenous and exogenous bronchdilators, thereby contributing to premenstrual asthma exacerbations.117

Treatment of Premenstrual Asthma

Proper management of premenstrual asthma requires an accurate diagnosis. A detailed history of the timing of exacerbations, accompanied by a patient diary of symptoms and peak expiratory flow rates is useful. The majority of patients will respond to increased dosages of the usual asthma medications (beta-adrenergic agonists, anticholinergics, and corticosteroids) during the luteal phase.117,123 Intramuscular progesterone was shown to be effective in three women with severe, refractory premenstrual asthma, eliminating the decrease in peak flow rate, as well as reducing total corticosteroid requirement.128 Exogenously administered estradiol did not ameliorate severe premenstrual asthma in a randomized clinical trial.129 There are two reports of the successful use of a GnRH agonist for women with recurrent menstrual-related status asthmaticus.130,131 The improvements seen with high-dose progesterone and GnRH agonists may be due to the resulting profound suppression of ovarian hormone production. Although there has been interest in the use of oral contraceptives in women with premenstrual asthma, the existing studies have shown highly variable effects on asthma symptoms.132–134

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder, diagnosed clinically by the triad of chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, altered bowel habits, and the absence of a structural or biochemical abnormality.135,136 Up to one third of otherwise asymptomatic women report an increase in gastrointestinal symptoms before and during menstruation.137 Reports of constipation during the progesterone-dominant luteal phase and loose stools or diarrhea at the onset of menses are common. Almost 50% of women with IBS will report a similar increase in bowel symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation.136–138 Progesterone has well-documented effects on the gastrointestinal system, including a reduction in lower esophageal sphincter tone and delayed gastric emptying.139 Delayed gastrointestinal transit time in women, particularly during the luteal phase, has also been demonstrated.140 Abrupt progesterone withdrawal may trigger an increase in bowel activity. Progesterone may also act as an endogenous antagonist of enteric nerve function.141

A recent study has shown that the exacerbation of IBS symptomatology at menses is associated with an increase in rectal sensitivity in women with IBS. A control group of healthy female volunteers did not demonstrate any changes in rectal sensitivity in relation to their menstrual cycles.142

Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation, are consistently reported by women with IBS.137,143,144 The most dramatic changes in bowel symptoms occur at the start of menstrual flow, a time when the levels of progesterone fall, and prostaglandin E2 and F2α, powerful stimulants of colonic contractility, rise.136 Patients with IBS, in whom the colon is hyperresponsive to a variety of stimuli, may have an exaggerated colonic response to prostaglandins released during menstruation.136

Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Treatment of IBS is generally symptomatic, including antispasmodics, promotility agents, and bulk-forming laxatives. The theory of prostaglandin involvement in menstrual-related exacerbations of IBS raises the possibility of treatment with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. Although there are other effective drug therapies for IBS, including antispasmodics and the newer serotonin receptor antagonists,145 studies investigating the efficacies of these therapies in women with menstrual exacerbations of IBS are lacking.

There have been several reports of successful treatment of severe, menstrually exacerbated IBS with GnRH agonists.146 With the menstrual cycle completely eliminated, these women experience significant and progressive improvement in bowel symptoms. Interestingly, many of these women experienced transient recurrence of their symptoms during the progestin phase of the estrogen and progestin addback therapy given to minimize the long-term adverse effects associated with GnRH agonists.146 It is likely that GnRH agonists have direct effects on the enteric nervous system, in addition to their indirect effects on the gut, mediated through ovarian hormone suppression.147 This possibility is supported by limited evidence that GnRH agonists provide relief from IBS in men and postmenopausal women.146 The expense and potential adverse effects of these medications will preclude prolonged use in most circumstances. Rarely, if dramatic relief results from a trial of ovarian suppression, oophorectomy may have a therapeutic role.

Diabetes

Menstrual cycle-related alterations in glycemic control during the luteal and premenstrual phases in some women with insulin-dependent diabetes (IDDM) have been reported.148–150 In one observational study of 406 women with IDDM, 67% reported changes in blood glucose control and 70% reported changes during menstruation. These changes were most pronounced in women experiencing PMS or sweet cravings during this time.151,152 Deterioration in glycemic control, diabetic ketoacidosis, severe insulin reactions, and hypoglycemic episodes may occur more frequently around menstruation.153 In one exceptional case, insulin resistance and ketoacidosis recurred exclusively during menstruation.154

Altered insulin receptor binding and affinity at different times during the menstrual cycle have been reported in some155–157 but not all studies.158 Attempts to identify the hormones responsible for menstrual cycle-related changes in carbohydrate metabolism have produced conflicting results. Impaired glucose tolerance during the luteal phase is reported in healthy women without diabetes.159 Studies on the effects of oral contraceptives and progestational agents on carbohydrate metabolism also show variable effects.160–162 It is possible that even small effects of estrogen and progesterone on glucose homeostasis are exaggerated in diabetic women, in whom the normal feedback regulation between plasma glucose levels and insulin secretion is lost.149

Poor eating behavior, such as binging or increased intake of sweets, is described by many women in the luteal phase and premenstrually152 and is another possible cause for loss of glycemic control in women with diabetes. Diabetic women should be counseled regarding the possibility of altered glycemic control. They need to recognize and anticipate changes in their eating patterns. Regular glucose monitoring, with appropriate anticipatory adjustment of insulin dosage and dietary intake, is a useful management strategy.97 Ovarian suppression with GnRH agonists has been used successfully in women with recurrent life-threatening complications, such as recurrent severe insulin reactions or ketoacidosis associated with specific phases of the menstrual cycle.150

Arthritis

Symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis often improve in the luteal phase when ovarian steroid production is maximal. Similarly, improvement is seen during pregnancy with exacerbation postpartum.163 A subjective increase in morning stiffness and arthritic pain during menstruation and the early follicular phase has been shown.164 Rudge and colleagues objectively documented menstrual cycle-related variations in rheumatoid arthritis by demonstrating a significant decline in mean grip strength at the start of menstruation.165 Similarly, finger joint size peaked within 6 days of the start of menses, corresponding in many cases with increased body weight.165

The abrupt decline of ovarian steroidogenesis resulting from involution of the corpus luteum is thought to be responsible for “menstrual arthritis,” a rare condition in which arthritis occurs exclusively at the time of menses.166 Cyclic alterations in rheumatoid arthritis may be attributable to menstrual cyclicity in the immune response.97 Both estrogen and progesterone have anti-inflammatory properties that may ameliorate arthritic symptoms.167 Premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms has also been attributed to altered pain perception associated with premenstrual mood alterations.165

Estrogen, either alone168 or in combination oral contraceptives,169,170 has proved beneficial for some women with rheumatoid arthritis. Oral contraceptives may delay onset of rheumatoid arthritis but do not prevent its occurrence.171,172 Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women does not appear to protect against the occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis.168

Other Disorders

The previous discussion describes the effects of the menstrual cycle on several relatively common disorders. Several rare conditions also show menstrual variation in severity. There are numerous case reports of catamenial pneumothorax, the occurrence of recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax exclusively associated with menses, possibly the result of pleural or diaphragmatic endometriosis.173,174 This has been successfully treated with GnRH agonists.175 There is some evidence that acute appendicitis presents more frequently in the luteal phase,176,177 although this could be due to the misdiagnosis of right lower quadrant pain resulting from corpus luteal cysts, leading to unnecessary appendectomy. Other disorders exacerbated by the postovulatory and premenstrual phases of the menstrual cycle include acne, endocrine allergy and anaphylaxis, hereditary angioedema, erythema multiforme, urticaria, aphthous ulcers, Behçet’s syndrome, acute intermittent porphyria, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, glaucoma, and multiple sclerosis.123,178–182 GnRH agonists have been used for some of these conditions, in particular for recurrent anaphylaxis and acute intermittent porphyria, when symptoms are severe or disabling.183–185 In contrast to these disorders, myasthenia gravis generally improves premenstrually.186 Although one early report indicated better outcomes if breast surgery was performed in the luteal phase,187 subsequent investigators have been unable to confirm this finding.188

CONCLUSION

1 Logue CM, Moos RH. Positive perimenstrual changes: Toward a new perspective on the menstrual cycle. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:31-40.

2 Lee KA, Rittenhouse CA. Prevalence of perimenstrual symptoms in employed women. Women Health. 1991;17:17-32.

3 Faratian B, Gaspar A, O’Brien PM, et al. Premenstrual syndrome: Weight, abdominal swelling, and perceived body image. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;150:200-204.

4 Ader DN, South-Paul J, Adera T, et al. Cyclical mastalgia: Prevalence and associated health and behavioural factors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22:71-76.

5 Reid RL. Premenstrual syndrome. Curr Prob Obstet Gynecol Fertil. 1985;8:1-57.

6 Reid RL, Yen SS. Premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;139:85-104.

7 Wood NF, Most A, Dery GK. Prevalence of perimenstrual symptoms. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:1257-1264.

8 Johnston SR, McChesney C, Bean JA. Epidemiology of premenstrual symptoms in a nonclinical sample. I. Prevalence, natural history, and help seeking behaviour. J Reprod Med. 1988;33:340-346.

9 Rivera-Tovar AD, Frank E. Late luteal phase dysphoric disorder in young women. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1634-1636.

10 Reid RL. Premenstrual syndrome. NEJM. 1991;324:1208-1210.

11 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:717-718.

12 Sassenrath EN, Rowell TE, Hendrickx AG. Perimenstrual aggression in groups of female rhesus monkeys. J Reprod Fertil. 1973;34:509-513.

13 Gilbert C, Gillman J. The changing pattern of food intake and appetite during the menstrual cycle of the baboon with a consideration of some of the controlling hormonal factors. S Afr J Med. 1956;21:75-89.

14 Kantero RL, Widholm O. Correlations of menstrual traits between adolescent girls and their mothers. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;14(Suppl):30-42.

15 Reid RL. Premenstrual syndrome: A time for introspection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:921-926.

16 Reid RL, Yen SS. The premenstrual syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1983;26:710-718.

17 Bjorn I, Bixo M, Nojd KS, et al. Negative mood changes during hormone replacement therapy: A comparison between two progestogens. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1419-1426.

18 Kirkham C, Hahn PM, Van Vugt DA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial to assess the side effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate in hormone replacement therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:93-97.

19 Steiner M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: An update. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:244-250.

20 Reid RL. Endogenous opioid activity and the premenstrual syndrome. Lancet. 1983;2:786.

21 Reid RL: Premenstrual syndrome. In DeGroot L (ed). Endotext.com. Available at: www.endotext.org. Accessed 1 January 2005.

22 Reame NE, Marshall JC, Kelch RP. Pulsatile LH secretion in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS): Evidence for normal neuroregulation of the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:205-213.

23 Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA. Estrogen–serotonin interactions: Implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:839-850.

24 Backstrom T, Andersson A, Andree L, et al. Pathogenesis in menstrual cycle-linked CNS disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1007:42-53.

25 Steiner M, Romano SJ, Babcock S, et al. The efficacy of fluoxetine in improving physical symptoms associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. BJOG. 2001;108:462-468.

26 Halbreich U, Kahn LS. Role of estrogen in the aetiology and treatment of mood disorders. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:797-817.

27 Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, et al. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:529-534.

28 Hahn PM, Wong J, Reid RL. Menopausal-like hot flushes reported in women of reproductive age. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:913-918.

29 Casper RF, Graves GR, Reid RL. Objective measurement of hot flushes associated with the premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:341-344.

30 Stearns V, Isaacs C, Rowland J, et al. A pilot trial assessing the efficacy of paroxetine hydrochloride (Paxil) in controlling hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:17-22.

31 Bendich A. The potential for dietary supplements to reduce premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms. J Am Coll Nutrition. 2000;19:3-12.

32 Cross GB, Marley J, Miles H, et al. Changes in nutrient intake during the menstrual cycle of overweight women with premenstrual syndrome. Brit J Nutr. 2001;85:475-482.

33 MacGregor GA, Markander ND, Roulston JE, et al. Is “idiopathic” edema idiopathic? Lancet. 1979;1:397-400.

34 Minton JP, Foecking MK, Webster DJ, et al. Caffeine, cyclic nucleotides, and breast disease. Surgery. 1979;86:105-109.

35 Rossignol AM, Bonnlander H. Caffeine-containing beverages, total fluid consumption, and premenstrual syndrome. Am J Publ Health. 1990;80:1106-1110.

36 Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Lex BW. Alcohol use and premenstrual symptoms in social drinkers. Psychopharmacology. 1990;101:448-455.

37 Diamond M, Simonson CD, DeFronzo RA. Menstrual cyclicity has a profound effect on glucose homeostasis. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:204-208.

38 Young SN. Clinical nutrition: 3. The fuzzy boundary between nutrition and psychopharmacology. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166:205-209.

39 Sayegh R, Schiff I, Wurtman J, et al. The effect of a carbohydrate-rich beverage on mood, appetite, and cognitive function in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:1-8.

40 Freeman EW, Stout AL, Endicott J, et al. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with a carbohydrate-rich beverage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:253-254.

41 Thys-Jacobs S, Starkey P, Bernstein D, et al. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: Effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. Premenstrual Syndrome Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:444-452.

42 Prior JC, Vigna Y, Sciarretta D, et al. Conditioning exercise decreases premenstrual symptoms: A prospective, controlled 6-month trial. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:402-408.

43 Steege JF, Blumenthal JA. The effects of aerobic exercise of premenstrual symptoms in middle aged women: A preliminary study. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:127-133.

44 Mira M, McNeil D, Fraser IS, et al. Mefenamic acid in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68:395-398.

45 Wood C, Jakubowicz D. The treatment of premenstrual symptoms with mefenamic acid. BJOG. 1980;87:627-630.

46 Bancroft J, Rennie D. The impact of oral contraceptives on the experience of perimenstrual mood, clumsiness, food craving and other symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:195-202.

47 Andersch B. The effect of various oral contraceptive combinations on premenstrual symptoms. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1982;20:463-469.

48 Graham CA, Sherwin BB. A prospective study of premenstrual symptoms using a triphasic oral contraceptive. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:257-266.

49 Freeman EW. Evaluation of a unique oral contraceptive in the management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Eur J Contracep Reprod Health. 2002;7(Suppl 3):27-34.

50 Yonkers KA, Brown C, Pearlstein TB, et al. Efficacy of a new low-dose oral contraceptive with drospirenone in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):492-501.

51 Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Jones PW, et al. Efficacy of vitamin B6 in treatment of premenstrual syndrome: Systematic review. BMJ. 1999;318:1375-1381.

52 O’Brien PM, Craven D, Selby C, et al. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome by spironolactone. BJOG. 1979;86:142-147.

53 Mauri M, Reid RL, MacLean AW. Sleep in the premenstrual phase: A self-report study of PMS patients and normal controls. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1988;78:82-86.

54 Harrison WM, Endicott J, Nee J. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoria with alprazolam: A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:270-275.

55 Berger CP, Presser B. Alprazolam in the treatment of two subsamples of patients with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder: A double blind placebo controlled crossover study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:379-385.

56 Landen M, Eriksson O, Sundblad C, et al. Compounds with affinity for serotonergic receptors in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria: A comparison of buspirone, nefazodone and placebo. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:292-298.

57 Steiner M, Korzekwa M, Lamont J, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. NEJM. 1995;332:1529-1534.

58 Dimmock PW, Wyatt KM, Jones PW, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: A systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131-1136.

59 Steiner M, Korzekwa M, Lamont J, et al. Intermittent fluoxetine dosing in the treatment of women with premenstrual dysphoria. Psychopharmacology Bull. 1997;33:771-774.

60 Pearlstein T, Joliat MJ, Brown EB, et al. Recurrence of symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder after cessation of luteal phase fluoxetine treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:887-895.

61 Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ, Rickels K, et al. A pilot naturalistic follow-up of extended sertraline treatment for severe premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:351-353.

62 Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Ismail KM, et al. The effectiveness of GnRH agonists with and without “add-back” therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: A meta-analysis. BJOG. 2004;111:585-593.

63 Maddocks S, Hahn P, Moller F, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of progesterone vaginal suppositories in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:573-581.

64 Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P, et al. Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in management of premenstrual syndrome: Systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:776-780.

65 Budeiri D, Li Wan Po A, Dornan JC. Is evening primrose oil of value in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome? Controlled Clin Trials. 1996;17:60-68.

66 Gorins A, Perret F, Tourant B, et al. A French double-blind crossover study (danazol versus placebo) in the treatment of severe fibrocystic breast disease. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1984;5:85-89.

67 Hahn PM, Van Vugt DA, Reid RL. A randomized placebo controlled crossover trial of danazol for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:193-209.

68 Messinis IE, Lolis D. Treatment of premenstrual mastalgia with tamoxifen. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1988;67:307-309.

69 Casper RF, Hearn MT. The effect of hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:105-109.

70 Casson P, Hahn P, VanVugt DA, et al. Lasting response to ovariectomy in severe intractable premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:99-102.

71 Marcus DA. Diagnosis and management of headache in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54:395-402.

72 Digre K, Damasio H. Menstrual migraine: Differential diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1987;30:417-430.

73 MacGregor EA. “Menstrual” migraine: Towards a definition. Cephalalgia. 1996;16:11-21.

74 MacGregor EA. Menstruation, sex hormones and migraine. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:125-141.

75 Granella F, Snaces G, Zanfeffari C, et al. Migraine without aura and reproductive life events: A clinical epidemiological study in 1300 women. Headache. 1993;33:385-389.

76 Stein GS. Headaches in the first postpartum week and their relationship to migraine. Headache. 1981;21:201-205.

77 Neri I, Granella F, Nappi R, et al. Characteristics of headache at menopause: A clinico-epidemiologic study. Maturitas. 1993;17:31-37.

78 Whitty CWN, Hockaday JM, Whitty MM. The effect of oral contraceptives on migraine. Lancet. 1966;1:856-859.

79 Dalessio DJ. Wolff’s Headache and Other Head Pain. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

80 Sommerville BW. The role of estrogen withdrawal in the etiology of menstrual migraine. Neurology. 1972;22:355-365.

81 Marcus DA. Serotonin and its role in headache pathogenesis and treatment. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:159-167.

82 Sommerville BW. Estrogen-withdrawal migraine. I. Duration of exposure required and attempted prophylaxis by premenstrual estrogen administration. Neurology. 1975;25:239-244.

83 Sommerville BW. Estrogen-withdrawal migraine. II. Attempted prophylaxis by premenstrual estrogen administration. Neurology. 1975;25:245-250.

84 Magos AL, Kilkha KJ, Studd JW. Treatment of menstrual migraine by oestradiol implants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46:1044-1046.

85 Wernke SM, Martin VT, Zoma WD, et al. The role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists with oestrogen add-back therapy in migraine prevention. Cephalalgia. 2001;21:449-450.

86 Ferrari MD, Roon KI, Lipton RB, et al. Oral triptans (serotonin 5-HT(1B/1D) agonists) in acute migraine treatment: A meta-analysis of 53 trials. Lancet. 2001;358:1668-1675.

87 Mannix LK. Management of menstrual migraine. Neurologist. 2003;9:207-213.

88 Newman LC, Lipton RB, Lay CL, Solomon S. A pilot study of oral sumatriptan as intermittent prophylaxis of menstruation-related migraine. Neurology. 1998;51:307-309.

89 Loder E. Prophylaxis of menstrual migraine with triptans: Problems and possibilities. Neurology. 2002;59:1677-1681.

90 DeLignières B, Vincens M, Mauvais-Jarvis P, et al. Prevention of menstrual migraine by percutaneous oestradiol. BMJ. 1986;293:1540.

91 Chavanu KJ, O’Donnell DC. Hormonal interventions for menstrual migraines. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:1442-1457.

92 Pfaffenrath V. Efficacy and safety of percutaneous estradiol vs placebo in menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia. 1993;13(Suppl):244.

93 Sarrell PM. Blood flow and ovarian secretions. In: Naftolin F, DeCherney A, Gutmann JN, Sarrel PM, editors. Ovarian Secretions and Cardiovascular and Neurological Function. New York: Raven Press; 1990:81-89.

94 Murray SC, Muse KN. Effective treatment of severe menstrual migraine headaches with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and “add-back” therapy. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:390-393.

95 Foldvary-Schaefer N, Falcone T. Catamenial epilepsy: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Neurology. 2003;61(6 Suppl):S2-S15.

96 Duncan S, Read CL, Brodie MJ. How common is catamenial epilepsy? Epilepsia. 1993;34:827-831.

97 Ensom MHH. Gender-based differences and menstrual cycle-related changes in specific diseases: Implications for pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:523-539.

98 Herzog AG, Klein P, Ransil BJ. Three patterns of catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38:1082-1088.

99 Bauer J, Burr W, Elger CE. Seizure occurrence during ovulatory and anovulatory cycles in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy: A prospective study. Eur J Neurol. 1998;5:83-88.

100 Cummings LN, Giudice L, Morrell MJ. Ovulatory function in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1995;36:355-359.

101 Klein P, Serje A, Pezzullo JC. Premature ovarian failure in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1584-1589.

102 Isojarvi JI. Reproductive dysfunction in women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;61(6 Suppl 2):S27-S34.

103 Backstrom T. Epileptic seizures in women related to plasma estrogen and progesterone during the menstrual cycle. Acta Neurol Scand. 1976;54:321-347.

104 Zimmerman AW. Hormones and epilepsy. Neurol Clin. 1986;4:853-861.

105 Mattson RH, Kamer JM, Cramer JA, et al. Seizure frequency and the menstrual cycle: A clinical study. Epilepsia. 1981;22:242.

106 Kumar N, Behari M, Aruja GK, et al. Phenytoin levels in catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1988;29:155-158.

107 Liporace JD. Women’s issues in epilepsy: Menses, childbearing and more. Postgrad Med. 1997;102:123-135.

108 Bäckström T, Zetterlund B, Blom S, et al. Effects of intravenous progesterone infusions on the epileptic discharge frequency in women with partial epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;69:240-248.

109 Dana-Haeri J, Richens A. Effect of norethisterone on seizures associated with menstruation. Epilepsia. 1983;24:377-381.

110 Herzog AG. Intermittent progesterone therapy and frequency of complex partial seizures in women with menstrual disorders. Neurology. 1986;36:1607-1610.

111 Herzog AG. Intermittent progesterone therapy of partial complex seizures in women with menstrual disorders. Neurology. 1986;36:1607-1610.

112 Herzog A. Progesterone therapy in women with epilepsy: A 3-year follow-up. Neurology. 1999;52:1917-1918.

113 Motta E, Rosciszewska D. Progesterone therapy in epileptic women with catamenial seizures. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 3):73.

114 Holmes GL. Effects of menstruation and pregnancy on epilepsy. Semin Neurol. 1988;8:234-239.

115 Bauer J, Wildt L, Flugel D, et al. The effect of a synthetic GnRH analogue on catamenial epilepsy: A study in ten patients. J Neurol. 1992;239:284-286.

116 Haider Y, Barnett DB. Catamenial epilepsy and goserelin. Lancet. 1991;338:1530.

117 Tan KS. Premenstrual asthma: Epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Drugs. 2001;61:2079-2086.

118 Settipane RA, Simon RA. Menstrual cycle and asthma. Ann Allergy. 1989;63:373-378.

119 Gibbs CJ, Counts II, Lock R, et al. Premenstrual exacerbations of asthma. Thorax. 1984;39:833-836.

120 Hanley SP. Asthma variation with menstruation. Br J Dis Chest. 1981;75:306-308.

121 Eliasson O, Scherzer HH, DeGraff ACJr. Morbidity in asthma in relation to the menstrual cycle. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;77(1 Pt 1):87-94.

122 Skobeloff EM, Spivey WH, Silverman R, et al. The effect of the menstrual cycle on asthma presentations in the emergency department. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1837-1840.

123 Boggess KA, Williamson HO, Homm RJ. Influence of the menstrual cycle on systemic diseases. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1990;17:321-342.

124 Pauli BD, Reid RL, Munt PW, et al. Influence of the menstrual cycle on airway function in asthmatic and normal subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:358-362.

125 Eliasson O, Densmore MJ, Scherzer HH, et al. The effect of sodium meclofenamate in premenstrual asthma: A controlled clinical trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;79:909-918.

126 Ozkaragoz K, Cakin F. The effect of menstruation on immediate skin reactions in patients with respiratory allergy. J Asthma Res. 1970;7:171-175.

127 Tan KS, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. Paradoxical down-regulation and desensitization of β2-adrenoceptors by exogenous progesterone in female asthmatics. Chest. 1997;111:847-851.

128 Beynon HLC, Garbett ND, Barnes PJ. Severe premenstrual exacerbations of asthma: Effect of intramuscular progesterone. Lancet. 1988;2:370-372.

129 Ensom MH, Chong G, Zhou D, et al. Estradiol in premenstrual asthma: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:561-571.

130 Murray RD, New JP, Barber PV, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues: A novel treatment for premenstrual asthma. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:966-967.

131 Blumenfeld Z, Bentur L, Yoffe N, et al. Menstrual asthma: Use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue for the treatment of cyclic aggravation of bronchial asthma. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:197-200.

132 Haggerty CL, Ness RB, Kelsey S, et al. The impact of estrogen and progesterone on asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:284-291.

133 Derimanov GS, Oppenheimer J. Exacerbation of premenstrual asthma caused by an oral contraceptive. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:243-246.

134 Tan KS, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. β2-adrenoceptor regulation and function in female asthmatic patients receiving the oral combined contraceptive pill. Chest. 1998;113:278-282.

135 Sandler RS. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in the U.S. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:409-412.

136 Whitehead WE, Cheskin LJ, Heller BR, et al. Evidence for exacerbation of irritable bowel syndrome during menses. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1485-1489.

137 Moore J, Barlow D, Jewell D, Kennedy S. Do gastrointestinal symptoms vary with the menstrual cycle? BJOG. 1998;105:1322-1325.

138 Heitkemper MM, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, et al. Symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:420-430.

139 Fisher RS, Robert GS, Graowski CJ, et al. Inhibition of lower esophageal sphincter circular muscle by female sex hormones. Am J Physiol. 1978;23:243-287.

140 Wald A, Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, et al. Gastrointestinal transit: The effect of the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1497-1500.

141 Mathias JR, Clench MH, Reeves-Darby VG, et al. Effect of leuprolide acetate in patients with moderate to severe functional bowel disease: Double-blind, placebo controlled study. Digest Dis Sci. 1994;39:1155-1162.

142 Houghton LA, Lea R, Jackson N, et al. The menstrual cycle affects rectal sensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome but not healthy volunteers. Gut. 2002;50:471-474.

143 Turnbull GK, Thompson DG, Day S, et al. Relationships between symptoms, menstrual cycle and orocaecal transit in normal and constipated women. Gut. 1989;30:30-34.

144 Heitkemper M, Jarrett M. Pattern of gastrointestinal and somatic symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:505-513.

145 Mertz HR. Irritable bowel syndrome. NEJM. 2003;349:2136-2146.

146 Mathias JR, Clenck MH, Roberts PH, Reeves-Darby VG. Effects of leuprolide acetate in patients with functional bowel disease: Long-term follow-up after double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Digest Dis Sci. 1994;39:1163-1170.

147 Wood JD. Efficacy of leuprolide treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Digest Dis Sci. 1994;39:1153-1154.

148 Magos A, Studd J. Effects of the menstrual cycle on medical disorders. Br J Hosp Med. 1985;33:68-77.

149 Widom B, Diamond MP, Simonson DC. Alterations in glucose metabolism during menstrual cycle in women with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:213-220.

150 Letterie GS, Fredlund PN. Catamenial insulin reactions treated with a long-acting gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1868-1870.

151 Cawood EH, Bancroft J, Steel JM. Perimenstrual symptoms in women with diabetes mellitus and the relationship to diabetic control. Diabet Med. 1993;10:444-448.

152 Tomelleri R, Gruewald K. Menstrual cycle and food cravings in young college women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1987;87:311-315.

153 Walsh CH, Malins JM. Menstruation and control of diabetes. BMJ. 1977;2:177-179.

154 Hubble D. Insulin resistance. BMJ. 1954;2:1022-1024.

155 De Pirro R, Fusco A, Bertoli A, et al. Insulin receptors during the menstrual cycle in normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;47:1387-1389.

156 Bertoli A, De Pirro R, Fusco A, et al. Differences in insulin receptors between men and menstruating women and influence of sex hormones on insulin binding during the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50:246-250.

157 Moore P, Kolterman O, Weyant J, et al. Insulin binding in human pregnancy: Comparisons to the postpartum, luteal, and follicular states. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52:937-941.

158 Pedersen O, Hjolland E, Lindsskov HO. Insulin binding and action on fat cells from young healthy females and males. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:E158-E167.

159 Jarrett RJ, Graver HJ. Changes in oral glucose tolerance during the menstrual cycle. BMJ. 1968;2:528-529.

160 Diamond MP, Wentz AC, Cherrington AD. Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism as they apply to reproductive endocrinology. Fertil Steril. 1988;50:387-397.

161 Godsland IF, Crook D, Simpson R, et al. The effects of different formulations of oral contraceptive agents on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. NEJM. 1990;323:1375-1381.

162 Spellacy WN. Carbohydrate metabolism during treatment with estrogen, progestogen, and low-dose oral contraceptives. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:732-734.

163 Ostensen M, Aune B, Husby G. Effect of pregnancy and hormonal changes on the activity of rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1983;12:69-72.

164 Latman NS. Relation of menstrual cycle phase to symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 1983;74:957-960.

165 Rudge SR, Kowanko IC, Drury PL. Menstrual cyclicity of finger joint size and grip strength in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983;42:425-430.

166 McDonagh JE, Singh MM, Griffiths ID. Menstrual arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:65-66.

167 Bodel P, Dillard GMJr, Kaplan SS, Malawista SE. Anti-inflammatory effects of estradiol on human blood leukocytes. J Lab Clin Med. 1970;80:373-384.

168 Da Silva JA, Hall GM. The effects of gender and sex hormones on outcome in rheumatoid arthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1992;6:196-219.

169 Kay CR, Wingrave SJ. Oral contraceptives and rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1983;1(8339):1437.

170 Linos A, Worthington JW, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Rheumatoid arthritis and oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1978;1:871.

171 Wingrave SJ, Kay CR. Reduction in incidence of rheumatoid arthritis associated with oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1978;1:569-571.

172 Spector TD, Hochberg MC. The protective effect of the oral contraceptive pill on rheumatoid arthritis: An overview of the analytic epidemiological studies using meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:1221-1230.

173 Maurer ER, Schaal FA, Mendez FL. Chronic recurring spontaneous pneumothorax due to endometriosis of the diaphragm. JAMA. 1958;168:2013-2024.

174 Markham SM, Carpenter SE, Rock JA. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:193-207.

175 Slabbynck H, Laureys M, Impens N, et al. Recurring catamenial pneumothorax treated with a GnRH analogue. Chest. 1991;100:851.

176 Arnbjonsson E. Acute appendicitis risk in various phases of the menstrual cycle. Acta Chir Scand. 1983;149:603-605.

177 Arnbjornsson E. The influence of oral contraceptives on the frequency of acute appendicitis in different phases of the menstrual cycle. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;158:464-466.

178 Dalton K. Influence of menstruation on glaucoma. Br J Ophthal. 1967;51:692-695.

179 Smith R, Studd JW. A pilot study of the effect upon multiple sclerosis of the menopause, hormone replacement therapy and the menstrual cycle. J Royal Soc Med. 1992;85:612-613.

180 Caughey SC, Margesson LJ, Reid RL. Erythema multiforme with ulcerative stomatitis at menstruation. Can J Obstet Gynecol. 1990:112-113.

181 Howard RE. Premenstrual urticaria and dermatographism. JAMA. 1981;245:1068.

182 Rosano GMC, Leonardo F, Sarrel P, et al. Cyclical variation in paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in women. Lancet. 1996;347:786-788.

183 Anderson KE, Spitz IM, Sassa S, et al. Prevention of cyclical attacks of acute intermittent porphyria with a long-acting agonist of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. NEJM. 1984;311:643-645.

184 Meggs WJ, Pescovitz OH, Metcalfe D, et al. Progesterone sensitivity as a cause of recurrent anaphylaxis. NEJM. 1984;311:1236-1238.

185 Slater JE, Raphael G, Cutler GB, et al. Recurrent anaphylaxis in menstruating women: Treatment with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist: A preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:542-546.

186 Vijayan N, Vijayan VK, Dreyfuss PM. Acetylcholinesterase activity and menstrual remissions in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40:1060-1065.

187 Badue RA. Timing of surgery during the cycle and breast cancer survival. Lancet. 1991;337:1261.

188 Wobbes T, Thomas CM, Segers MF, et al. The phase of the menstrual cycle has no influence on the disease-free survival of patients with mammary carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:599-600.