CHAPTER 14 PREHOSPITAL CARE OF BIOLOGICAL AGENT–INDUCED INJURIES

On a busy Baghdad bridge spanning the great Tigris River coursing Iraq from north to south, a crowd of people intermingled in their bidirectional flow. Most were hurrying to and from the nearby market on the east side of the river below. Some were carrying parcels, others infant children in their arms or on their backs. Someone shouted something; it was never determined who or what, but those within hearing interpreted the alarm as a warning, presumably of an improvised explosive device (IED) on the bridge. The reaction among the already apprehensive civilians was instant panic and they scattered in all directions. Some attempted to cross to the other side; others tried to retreat from where they were headed, some jumped into the waters below. A herd mentality eliminated all sense of proportion; flight with presumed escape dominated the thought processes of the terrified populace. In the aftermath of the incident, almost 1000 were dead and many more were injured. The causes of death included suffocation, exsanguination from blunt trauma to torso, head injuries, and multiple long-bone fractures. Many drowned. The alleged IED never detonated, nor was it ever identified. The date was August 31, 2005. The inciting event remains a mystery.1 The inciting event, however, exemplifies two phenomena pertinent to the trauma surgeon.

Prehospital care is provided by the most medically sophisticated at the scene and en route to a medical treatment facility (MTF). Such caregivers may be emergency medical technicians (EMTs), paramedics, and even physicians.2 They will be required, by necessity, to perform patient assessment, threat assessment, triage, and first aid until additional help arrives.

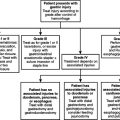

Triage is patient-location dependent.3 Casualties from biological agent–induced injuries may be encountered in the field or at the scene of agent exposure. At this level the term “field triage,” as distinguished from “hospital triage,” is appropriate. The word is derived from the French verb “trier,” which means to sort, and dates back to the 15th century and European marketplaces where fur and fiber were sorted according to quality and price. Any number of categories can be designated, but perhaps the simplest is three tiers. Most “patients” are apprehensive, bordering on hysteria. They need to be conveniently relocated and comforted by a minimal number of caregivers. This category may comprise the largest percentage of patients at the scene. A small percentage of the remainder are in extremis or agonal. They are termed “expectant,” and cannot be helped other than to allow them to die with a minimum of discomfort and as much dignity as can be provided under the circumstances. The remainder are “priority,” and they all need transport to an MTF. These patients are bleeding, have airway problems, head injuries, burns, chest or abdominal pain, or evidence of spine or long-bone fracture. This latter category may represent only 20% of the casualties, but it is the most important.

Principles of triage3 that must be understood include the fact that patients are triaged and re-triaged, not only at all levels of patient care, but also within levels of patient care. The triage officer does not treat, assuming there is more than one caregiver present. The triage officer only sorts patients according to injury and probable outcome. The latter is dependent on available resources—time, personnel, and equipment—and their presumed efficient use. Weather, communications, and available transportation will all play critical roles in determining anticipated outcome. Assuming that explosive ordinance, radiation, and chemical threats have been eliminated, but a biological agent has not, what steps should be taken by the first responder or caregiver present at the scene of an ACT?4

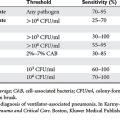

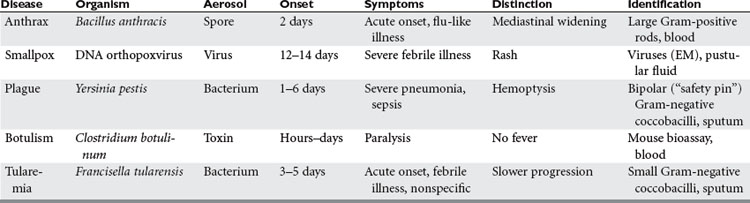

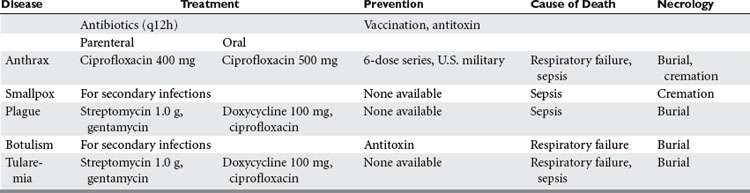

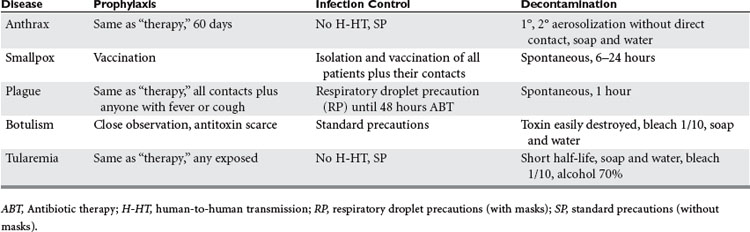

At present, there are five specific agents considered likely sources of bioterrorism. They have several general characteristics in common that make them preferable to alternative agents. These characteristics include relative ease of production, packaging, transport, and delivery, as well as not only lethality, but also morbidity. Agents that kill rapidly may be less inducive of panic and terror than those that cause large numbers to be extremely ill for prolonged periods of time, their condition apparently communicable. The five agents most commonly cited, as potential threats, are those associated with anthrax, smallpox, botulism, plague, and tularemia. The characteristics of each will be presented with emphasis placed on detection, diagnosis, treatment, precautions, prophylaxis, quarantine, decontamination, and necrology (Tables 1,2, and 3). Other less likely agents, such as the encephalitides, the Ebola virus, and so on, will be mentioned, but only in passing, because of their much lower probability of encounter.

Table 1 Five Most Frequently Cited Bioterrorism Agents: Characteristics, Associated Disease, Recognition, and Identification

Table 2 Five Most Frequently Cited Bioterrorism Agents: Treatment, Prevention, Cause of Death, and Necrology

Table 3 Five Most Frequently Cited Bioterrorism Agents: Prophylaxis, Infection Control, and Decontamination

Anthrax5 has a long history as a disease among animals, but is much less commonly encountered in humans. Spores of Bacillus anthracis have been weaponized by the governments of many countries and individuals have been exposed accidentally in Russia as well as targeted by attacks in Japan and more recently the United States. While the number of deaths from these exposures is relatively small, the potential is impressive. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that aerial release of 50 kg of anthrax spores over an urban population of 5 million, would cause 250,000 casualties, almost half of whom would die without treatment. Similar scenarios have compared an aerosolized attack with anthrax spores to the effects of a hydrogen bomb attack on a large city.

Three forms of anthrax infection delivery occur in humans: inhalation, cutaneous, and gastrointestinal. Anthrax spores are 1.0 mcm, extremely hardy, and, when aerosolized, odorless, tasteless, colorless, and invisible. Obviously bioterrorists would most likely attempt inhalation exposure via an aerosolized release of spores from an aerial source. A two-stage illness ensues. In the primary phase, which lasts hours to days, the victim experiences fever, dyspnea, cough, headache, nausea, vomiting, chills, weakness, and pain in the chest and abdomen within days to weeks of exposure, depending on number and size of spores inhaled. The second phase begins with an abrupt increase in severity of symptoms, which coincides with massive lymphadenopathy, bacteremia, hypotension, and death, if untreated. The massive hilar lymphadenopathy presents radiographically as a “widened mediastinum.” Mediastinitis, meningitis, and cyanosis are common in the second phase. Clues to the diagnosis are the sudden appearance, in large numbers, of previously healthy city dwellers with an overwhelming flu-like illness. Differential diagnosis includes pneumonic plague. Treatment includes parenteral antibiotics (penicillin, etc.), ventilator and pressors if patients can be hospitalized, and if not, oral antibiotics. Blood cultures before antibiotic therapy are confirmatory, but case fatality rates approach 80% and most of those occur within the first 2 days of symptoms.

Prophylaxis consists of vaccination (six-dose series),6 which has been administered to all U.S. service personnel. Since there is no threat of patient-to-patient transmission of anthrax, patient contacts do not require treatment; however, the dead should be cremated because of spore hardiness. Decontamination of all suspected victims of inhalation anthrax is necessary to avoid secondary aerosolization of spores that remain on clothing, etc. Health care workers must wash their hands after contact with anthrax victims for the same reason.

Perhaps the most feared of the biological agents on the top five lists for likely agents of bioterrorism is smallpox.7 It is especially threatening for several reasons. Since global eradication through vaccination was declared almost 30 years ago, vaccination has been terminated. Thus, no one today is protected from a smallpox attack even though the only known sources of the virus are in state-controlled laboratories in the United States and Russia. In addition, there is no known treatment for smallpox. Person-to-person contact enables aerosol transmission of body secretions, and contaminated clothing, as well as bedding, readily holds as well as transmits the virus from patient to contacts. Only a few viruses are necessary for infection to progress to viremia, which lasts a few days. The hemopoietic and reticuloendothelial systems are inoculated, and a secondary, heavier viremia results within 8 days. Victims exhibit high fever, malaise, headache, prostration, backache, and abdominal pain. A characteristic vesicular skin eruption progresses centrifugally and involves the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, which distinguishes smallpox (variola) from chicken pox (varicella). The former lesions conform to a single stage, whereas those of varicella appear in crops and also occur centripetally. Treatment of smallpox consists of supportive measures, including antibiotics, but case fatality is in excess of 30%. Contacts need vaccination, and this of course includes all exposed health care workers, including all those who have had contact with the victim. Patients must be isolated and can be confined to a designated hospital, and even their home where possible. The incubation period is 12–14 days, and the subsequent viremia progresses as outlined previously. Since the patients remain heavily infective, even in death, cremation is necessary as with victims of anthrax.

Although perhaps most feared as an agent for bioterrorism, world condemnation of smallpox use for such purposes coupled with the very difficult, virtually impossible access to sufficient stores of the virus make it extremely impractical. Nonetheless, because Russia remains somewhat unpredictable, and because Russia and the United States may not be the only repositories for the virus,8 the threat remains and so must the registration of smallpox in all bioterrorism training programs in the United States and elsewhere.

Plague has its own history of bioterrorist use, and rivals any other biological agent in terms of numbers killed, certainly as a percentage of world population, including the Great Influenza of 1918.9 Plague is high on the list of choices for current bioterrorists because of ready availability, ease of production, and applicability to aerosolization. It is estimated that 50 kg of Yersenia pestis, the causative organism, aerosolized over an urban population of 5 million, would result in pneumonic plague in 150,000, of whom 36,000 would die. The organisms would be expected to survive within the area for 1 hour and remain a threat during that time. Because pneumonic plague can be transmitted from one person to another, panic and flight could readily spread the initial infection. The disease presents as a severe respiratory illness 1–6 days following exposure. Since actual exposure may not be known, the clue to recognition of pneumonic plague is its nearly simultaneous presentation in a relatively large number of previously healthy individuals with negligible risk factors. Historically, plague was anticipated in the wake of large numbers of dead and dying rats in an urban population, causing the fleas carrying the bacilli to turn to humans as hosts. In a terrorist attack, however, this phase of the life cycle would be obviated. The disease in humans became known as the “Black Death” from the acral cyanosis associated with digital vasospasm and gangrene associated with septicemic plague, a complication of any form of infection with Y. pestis. Others attribute the term to the intense, generalized cyanosis coincident with pneumonic plague and its resultant hypoxia. Since the prodroma of pneumonic plague include coryza, a sneeze in the 14th century was greeted with “God bless you” by those in attendance who quickly scurried away because the presumption was that the person who sneezed was about to come down with the plague, for which there was no treatment and death almost a certainty.

Because of its similarity to anthrax, several distinguishing features are mentioned. Hemoptysis is more suggestive of pneumonic plague than the pneumonia caused by anthrax. Sputum from patients with plague reveals Gram-negative coccobacilli that have been likened to “safety pins” in appearance because of their bipolar nuclei.10 Treatment is with parenteral antibiotics (tetracycline, gentamycin) preferably; but, faced with large numbers of patients and limited hospital space, oral tetracycline, doxycycline, or ciprofloxacin is recommended. A vaccine was developed for prevention against bubonic plague, but offers little protection against pneumonic plague contracted from aerosalization, and in fact, it is no longer manufactured. Once the organism is identified, health care providers should isolate patients because they remain infective and those in attendance should implement standard respiratory droplet precautions (SRDP), which include mask and eye screens in addition to gown and gloves. Patients who do not survive can be buried because the organisms will not survive. Environmental precautions are usually not a concern because the organisms have a limited life expectancy following release (1 hour).

A fourth agent for bioterrorism is botulinum toxin,11 considered the most poisonous substance known to mankind. Aerosolization of 1 g of the toxin, if adequately dispersed and inhaled by those exposed, could kill 1 million people. One-tenth of 1 mcg, intravenously, is sufficient to kill an adult. The toxin blocks acetylcholine release at neuromuscular junctions, and it does so by binding irreversibly with the cholinergic synapse. The clinical picture then is a classic triad of symptoms: (1) symmetric, descending flaccid paralysis with prominent bulbar palsies, in (2) an afebrile patient, with (3) a clear sensorium. The bulbar palsies are often referred to as “the 4Ds”: diplopia, dysphoria, dysarthria, and dysphagia. Recovery from inhalation botulism requires intensive care and ventilatory and nutritional support, and may take weeks to months because neural regeneration is required to displace the previously blocked synapses at myoneural junctions. For this reason alone—the prolonged disability and delayed recovery of so many victims—the toxin is a highly prized agent of bioterrorism. In fact, prior to the outbreak of the Gulf War in 1991, Iraq is said to have stockpiled and weaponized enough botulinum toxin to kill three times the world’s population. The toxin is easily produced, and readily stored and transported, as well as delivered, to a target.

What might be expected at the prehospital phase of the bioterrorist attack with aerosolized botulinum toxin? The agent, like anthrax spores, even in large volume and concentration, is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and invisible. Hence, its detection would go unnoticed, at least initially. Symptoms might not appear for an hour and for obvious reasons. Experience with human inhalation botulism is very limited.12 In its only delivery against civilians, Japanese terrorists failed on three occasions in the early 1990s to injure anyone, presumably for technical reasons. Nonetheless, word of the attacks did terrorize those in attendance. Many who fled the scene sustained injuries, but the final report concluded “non-toxin casualties were light.” Had the population been forewarned of a possible attack or, like the Iraqi civilians on the bridge mentioned earlier, been subjected to potential terror attacks for several years before, the ensuing panic could have been infinitely more injurious to those present. Add to that possibility the likelihood that symptoms occurred more rapidly and word spread among the crowd that death was imminent unless the victims could reach a major treatment facility. Pandemonium would ensue and nearby hospitals would be inundated and overwhelmed within a matter of minutes. Such examples point to the need for education of the populace, and those who care for them in the field and at the MTF. The former need to know that they should avoid panic, await instructions, leave the area, and listen to the radio and other media for further information and instructions. Similarly, hospital and field staff must be notified of probable patient surge and agent, and the latest diagnostic treatment and reporting algorithms to follow. Prehospital teams—EMTs, paramedics, and first responders—should assess the scene for symptomatic victims who need to be transported expeditiously to the MTF.

Francisella tularensis,13 a small, nonmotile, aerobic, Gramnegative coccobacillus, is responsible for tularemia in humans and is one of the most infectious pathogenic bacteria known to humankind. Inoculation or inhalation of as few as 10 organisms is sufficient to cause disease. For this reason, its extreme infectivity, the ease of its dissemination, and its capacity to cause severe illness, even death, F. tularensis is a likely agent for use in bioterrorism. WHO estimated that 50 kg of live organisms, aerosolized over an urban population center of 5 million, would cause 250,000 casualties including 19,000 deaths.

The result of an aerosolized release of F. tularensis would be a large number of patients with an unusual respiratory disease 3 to 5 days after inhalation. A high index of suspicion is again needed to distinguish tularemia from community-acquired infections such as influenza or atypical pneumonia. If a bioterrorist attack is suspected, the differential diagnosis includes other agents of bioterrorism such as plague, anthrax, and, yet to be discussed, Q-fever. Tularemia generally has a slower progression of symptoms and a lower case fatality rate. Plague progresses to hemoptysis, respiratory failure, sepsis, and shock, which are not usually seen in tularemia. Anthrax has a characteristic radiographic appearance (widened mediastinum), which is not seen in tularemia. Culture from sputum establishes the diagnosis, although light microscopy of sputum may reveal the Gram-negative coccobacilli. Treatment consists of parenteral antibiotics, such as streptomycin or gentamycin, under ideal conditions.14 When mass casualties exceed, numerically, the facilities for parenteral antibiotics, oral doxycycline or ciprofloxacin are substituted. Vaccination is not useful because of the very short incubation period of the organism in humans. Patients need not be isolated since person-to-person transmission does not occur. Standard precautions are all that is necessary for patient care providers. Environmental decontamination is minimally problematic because of the presumed short half-life of the organism exposed to environmental factors such as desiccation and solar radiation. Alcohol, soap and water, and household bleach (dilute) are decontaminants if there is concern about additional potential contamination of equipment or other materials.

Other agents are available and the list of possibilities is extensive. We will conclude, as indicated earlier, with a brief presentation of other agents that are often mentioned, but thought less likely to be deployed than “the big five” discussed previously. Included here are Q-fever, Staphylococcal enterotoxin B, the equine encephalitides, and the hemorrhagic fever viruses.15 Each has a special characteristic that makes it attractive to bioterrorists, but also at least one that makes it less likely to be used than one of the big five.

Q-fever is the cause of a flu-like illness that results from inhalation of the etiologic agent, Coxiella burnetii.15 The latter has been called a rickettsia by some, and a bacterium by others. It is for this reason that the resultant disease derives its name. “Q” stands for “query,” indicating the enigma surrounding its definition. The terrorist appeal relates to the organism’s high infectivity. This “asset” is countered by a relatively low lethality and self-limited clinical course. Diagnosis is problematic, a high index of suspicion is necessary, and confirmation requires serological testing. Treatment, if necessary, is antibiotic (doxycycline).

Staphylococcal enterotoxin B is an exotoxin that can be aerosolized, and when inhaled results in sepsis. Its appeal is its ability to produce an incapacitating illness that would persist long enough to spread terror, even panic, among a large number (essentially all) of those exposed. Theoretically, the living can more readily dramatize the threat than can the dead because the former remain vocal. The “disadvantage” of the agent for bioterrorists is its very low lethality and ease of therapy, which is largely supportive. Diagnosis again depends on a high index of suspicion, and identification is based upon serological confirmation. Of concern is the potential mixture of agents for aerosolization that would cause obvious confusion among caregivers and heighten the terror and panic.

Since victims of bioterrorism may seek different treatment facilities and because onset of symptoms may not always be synchronous, health care deliverers must have surveillance systems in place so that any “flu-like illness,” unusual in number or presentation, is reported to all regional health care facilities. This practice is essential for early detection of an otherwise silent bioterrorist attack.16,17 What else can be done in preparation for such an event?

1 BBC, World News, 31 August 2005

2 Clements BW, Evans RG. The doctor’s role in bioterrorism. Lancet. 2004;364:26-27.

3 Swan KG, Swan KGJr. Triage: the past revisited. Mil Med. 1996;8:448-452.

4 Fry DE, Schecter WP, Parker JS, et al. The surgeon and acts of civilian terrorism: biologic agents. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:291-302.

5 Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon. JAMA. 1999;281:1735-1745.

6 Fowler RA, Saunders GD, Bravata DM, et al. Cost effectiveness of defending against bioterrorism: a comparison of vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis against anthrax. Ann Intern Med. 2005;42:601-610.

7 Henderson DA, Inglesby TV, Bartlett JG, et al. Smallpox as a biological weapon. JAMA. 1999;281:2127-2137.

8 Beeching NJ, Dance DAB, Miller ARO, Spencer RC. Biological warfare and bioterrorism. BMJ. 2002;324:336-339.

9 Inglesby TV, Dennis DT, Henderson DA. Plague as a biological weapon. JAMA. 2000;283:2281-2290.

10 Franz DR, Zajtchuk R. Biological terrorism: understanding the threat, preparation and medical response. Dis Mon. 2002;48:489-564.

11 Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, et al. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon. JAMA. 2001;285:1059-1070.

12 Karwa M, Currie B, Kvetan V. Bioterrorism: preparing for the impossible or the improbable. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:575-595.

13 Dennis DT, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon. JAMA. 2001;285:2763-2773.

14 Eachempati SR, Flomenbaum N, Barie PS. Biological warfare: current concerns for the health care provider. J Trauma. 2002;52:179-186.

15 Gosden C, Gardener D. Weapons of mass destruction—threats and responses. BMJ. 2005;331:397-400.

16 Moran GJ, Talon DA. Update on emerging infections: news from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:414-418.

17 Bravata DM, McDonald KM, Smith WM, et al. Systemic review: surveillance systems for early detection of bioterrorism-related diseases. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:910-922.