CHAPTER 15 Pregnancy: Third Trimester

CONSTIPATION DURING PREGNANCY

Constipation is defined as having bowel movements fewer than three times per week. The stools are typically hard, dry, small in size, and difficult to eliminate. Constipation may be accompanied by straining, pain, bloating, cramping, and the sensation of a full bowel. It is a bothersome common complaint of pregnancy, particularly in the second and third trimesters. Women who are habitually constipated may become more so during pregnancy. The prevalence of constipation in pregnancy is reported to be 11% to 38%.1 It has been generally accepted that decreased gastric motility in pregnancy is a result of increased circulating progesterone levels. More recent experimental evidence suggests that elevated estrogen concentrations are involved in delayed motility through an enhancement of nitric oxide release.1,2 Slow transit time of food through the intestinal tract leads to increased water absorption and thereby to constipation. Dietary factors, particularly inadequate fiber intake and lack of exercise, contribute to constipation, as does increased pressure of the growing uterus on the rectum as pregnancy becomes advanced.3 Ignoring the urge to have a bowel movement can also contribute to the problem. Iron-deficiency anemia can contribute to constipation, as can elemental iron supplements (see Chapter 16).

DIAGNOSIS

Constipation first presenting in pregnancy does not require an extensive evaluation, and is considered a normal pregnancy complaint.4 Constipation accompanied by other symptoms, for example, blood in the stools, or unresponsive to treatments requires further investigation to rule out possible pathology.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT OF CONSTIPATION

Most patients respond to simple dietary and lifestyle measures. Treatment during pregnancy is similar to that for the general population; however, special care must be taken to avoid medications that may be harmful to the fetus or disrupt the pregnancy.4

The first line of treatments for constipation include:

Fiber Supplementation: Bulk-Forming Laxatives

Fiber supplements, which are bulk-forming laxatives, are effective, safe, and without side effects when used in appropriate doses; however, limited studies are available on the use of laxatives in pregnancy.1 In addition to

softening the stool by keeping more fluid in the bowel lumen, the presence of the increased bulk is thought to stimulate intestinal peristalsis.5 Examples include wheat fiber (e.g., wheat bran), psyllium, flax seed, and pectin, to 25 g per day.6 Laxative effects may take 3 to 7 days to be noticeable. If side effects occur, switching to a different bulk laxative may help. Taken in excessive qualities they can lead to cramping, gas, diarrhea, and bloating.4,6 Bulk laxatives have a pregnancy B category (Table 15-1).4,6 Stool softeners are not recommended for use during pregnancy.

| CATEGORY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| A | Adequate, well-controlled studies in pregnant women have not shown an increased risk of fetal abnormalities. |

| B |

Adapted from Meadows M: Pregnancy and the drug dilemma, FDA Consum 35(3):16-20, 2001.

Osmotic Laxatives

Osmotic laxatives are indigestible sugars that work by increasing the amount of fluid that is retained in the bowel. Sorbitol, lactulose, and glycerin appear to be safe sources for use during pregnancy. Saline, phosphorus, and magnesium salt laxatives, including many prepackaged enemas, are not advisable during pregnancy because they can cause salt retention in the mother.7

Stimulant Laxatives

Stimulant laxatives are best used in pregnancy only after other measures have failed to relieve constipation. Examples of stimulant laxatives include senna, cascara sagrada, and aloes. Of these, only senna is considered safe (see senna discussion in the following) for use during pregnancy. Approved as an over-the-counter (OTC) medication, senna is an herb and is thus discussed in the following section with other botanicals. Stimulants are more likely to cause side effects of diarrhea and abdominal pain than are bulk laxatives.8

BOTANICAL TREATMENT FOR CONSTIPATION

Botanical treatment for constipation relies on a combination of the practical dietary and lifestyle changes presented on the preceding page, and gentle herbs that increase bulk and moisture in the bowel, or gently stimulate bowel activity. These herbs may be used singly, or in combination, and are combined with a carminative herb—one that relieves gas and griping—to prevent side effects sometimes associated with laxatives. Examples of carminatives that can be safely used for short durations during pregnancy include ginger root and anise seed. Stimulant laxatives are used only for short durations (up to 2 weeks) to avoid dependence. When using herbal bulking laxatives, it is important to make sure the patient is drinking plenty of water, because the bulk laxative will absorb large amounts of water from the colon. There have been few studies evaluating the safety or efficacy of natural laxatives in pregnancy. A number of herbal preparations available in health food and grocery stores contain herbs that are not appropriate or safe for use in pregnancy, including cascara sagrada, aloe, and buckthorn (see Case History 1). Aloe may be teratogenic, whereas the other herbs are associated with increased uterine activity. Practitioners should inquire of their pregnant patients whether they are using preparations containing these herbs if constipation is a problem and direct them to safer food-based, lifestyle, and herbal alternatives.

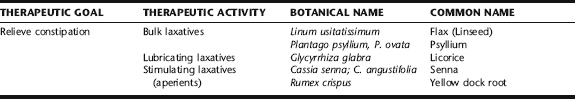

Foods and food agents commonly used to relieve constipation include wheat bran, which is a high-fiber source, prunes (soaked in water or apple juice until soft and plump), and fruits high in sorbitol, including apples, pears, apricots, and cherries. Molasses is both high in iron and a gentle laxative, and therefore excellent for constipation associated with anemia.9 Commonly used herbs are listed in Table 15-2, and discussed below. In traditional Chinese medicine constipation is considered a symptom of blood deficiency, and may be treated with Dong Quai and Peony formula, discussed under iron deficiency anemia.

Discussion of Botanicals for Constipation during Pregnancy

Psyllium Seed and Husk

Psyllium seeds, as well as Ispaghula seeds, which have comparable activity, are bulk laxative agents.10 Psyllium seeds shorten bowel transit time by increasing the intestinal contents and stimulating stretch receptors and thereby peristalsis. The whole seeds or husks are soaked in water or apple juice for several hours and then they are taken with a large amount of liquid. Bowel movements are usually achieved within 6 to 12 hours after taking the preparation.5 Rarely, allergic reactions have occurred.5 The preparation should not be taken by patients with swallowing difficulties because choking can occur.

Senna Leaf and Pod

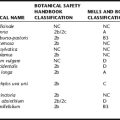

Senna, a quick-acting, reliable stimulating laxative generally, is taken as a tea. Its mechanism of action is primarily via anthracoids (sennoside A and B), or anthraquinone glycosides. Senna is considered appropriate for use in acute cases, and is not considered an herb to be used regularly. When used alone it can elicit loose stool with significant griping, and is therefore traditionally combined with a small amount of ginger root, anise seed, fennel seed, spearmint, or peppermint for their carminative action (see Formula 1 in Box 15-2). There is significant disagreement in the literature regarding the safety of senna use during pregnancy. Modern herbalists have tended to consider it contraindicated for use during pregnancy, with the supposition that the markedly increased bowel peristalsis stimulated by the herb might lead to reflex uterine activity and thus may have indirect emmenagogic effects. The herb is commonly found on lists of herbs contraindicated during pregnancy. The Botanical Safety Handbook classifies senna as a Class 2b herb, not to be used during pregnancy or lactation unless otherwise directed by an expert qualified in the appropriate use of this substance.14 According to the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP) there no reports of undesirable or damaging effects during pregnancy or on the fetus when senna is used in accordance with the recommended dosing and use schedule. However, because of experimental data concerning a genotoxic risk from several anthracoids (emodin and aloe-emodin), the herb should be avoided during the first trimester or taken only under medical supervision.15 Two studies reported that human and animal data do not support concerns that senna laxatives pose a genotoxic risk to humans when taken properly. 16 17 18 A review article reported that senna appears to be the most appropriate stimulant laxative to use during pregnancy.19 Small amounts of active metabolites are excreted in the breast milk, and though these do not appear to have a laxative effect in the newborn, its use is not recommended during lactation.15 The dose recommended by ESCOP is individualized to the smallest possible dose that produces a comfortable, soft, formed stool. Weiss states that small doses of 1 to 2 g soften the stools within 5 to 7 hours.10 It is recommended that the herb be used only short-term for occasional constipation. Senna preparations are typically taken at bed time to produce a bowel movement the following morning.

BOX 15-2 Formulas for Constipation

Formula 1: Laxative Tea (adapted from the German Standard Registration)5

| Senna leaf | (Cassia senna) | 15 g |

| Anise seed | (Pimpinella anisum) | 3 g |

| Chamomile blossoms | (Matricaria recutita) | 5 g |

| Spearmint leaf | (Mentha spicata) | 5 g |

| Total: 28 g (1 oz) | ||

Formula 2: Dandelion-Yellow Dock Syrup

| Yellow dock root | (Rumex crispus) | 14 g |

| Dandelion root | (Taraxacum officinale) | 14 g |

Yellow Dock Root

Yellow dock is sometimes contraindicated during pregnancy because of its anthraquinone glycoside contents. Clinically, it is widely used by midwives as a gentle stimulating laxative because it is effective yet much milder than senna, which is generally avoided when possible. According to the Botanical Safety Handbook, this herb contains only a small amount of anthraquinone glycosides and has a mild laxative effect.14 Limited maternal use has not been observed to cause any increase in fetal malformation or other harmful effects to the fetus.20 The use of yellow dock for constipation is illustrated in yellow dock dandelion root syrup, and in the case history in iron deficiency anemia.

Licorice Root

Herbalists favor the use of licorice root for its intestinal moistening abilities. According to Wichtl et al., licorice root is included in laxative herbal tea formulas because it potentiates the activity of anthraquinone-containing herbs (e.g., senna), lowering the required dose of the anthraquinone laxative.11 Because of its effects on glucorticoids, excessive doses (>50 g per day) over a prolonged period can result in hypokalemia, hypernatremia, edema, hypertension, and cardiac disorders, and in extreme cases, pseudoaldosteronism. Symptoms disappear within days of discontinuation of the herb.11 Two recent reports on high-dose licorice consumption, in the form of licorice candy containing actual glycyrrhizin-containing licorice, during pregnancy, demonstrated no increase in maternal hypertension or low birth weight; however, both studies, demonstrated a significant increased in preterm (<37 weeks) delivery. In one study, the risk of preterm delivery was greater than double the risk of women not consuming licorice.12,13 No studies demonstrate harm or adverse outcomes with short-term use of modest doses of licorice. It is recommended that licorice not be used in excessive doses or for prolonged periods during pregnancy, rather, as with senna, it be used for acute use for up to several days at a time.

HYPERTENSION IN PREGNANCY

Hypertension is the most common medical problem of pregnancy, affecting 10% of all pregnant women.21 The condition can lead to devastating outcomes with significantly increased risks of placental abruption, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), cerebral hemorrhage, hepatic failure, and acute renal failure.22 Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a significant cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, and therefore require accurate diagnosis and proper medical management. CAM treatments for hypertensive disorders during pregnancy should always accompany proper medical management in conjunction with the care of an obstetrician.

Hypertension itself is defined as a sustained increase in blood pressure >140/90. Elevated blood pressure should be documented on at least two consecutive occasions greater than 6 hours apart, using the appropriate-size blood pressure cuff, to make a diagnosis of hypertension. Diastolic pressure should be considered the number at which the Phase V Korotkoff sound is auscultated. Patients should be told to avoid tobacco and caffeine for at least 30 minutes prior to a blood pressure reading, and should be encouraged to relax for 10 minutes prior to evaluation.22 The definition of hypertension as a 30 mm Hg systolic and/or 15 mm Hg rise over baseline is now considered invalid, as it is recognized that up to 73% of all women in their first pregnancies experience a diastolic rise of this magnitude at some point in the pregnancy with no subsequent development of pathology.23 Nonetheless, close observation of these women is recommended.21 Each type of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy has specific diagnostic criteria (Box 15-3).

BOX 15-3 Diagnosis of Hypertensive Disorders Complicating Pregnancy

Note that edema is no longer considered a diagnostic criterion of preeclampsia as it is found in many normal pregnancies and is not a reliable indicator.

Preeclampsia Superimposed on Chronic Hypertension

DESCRIPTIONS OF HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS OF PREGNANCY BY CLASSIFICATION AND GENERAL CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is a disease specific to pregnancy, with “cure” occurring only upon delivery of the placenta. The etiology of preeclampsia remains unknown, although there are numerous theories. It appears that it is a complex, multifactorial condition with genetic factors, immunologic factors, altered inflammatory pathways, insulin resistance (obesity, hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance), endothelial dysfunction, macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies, altered placental angiogenesis, and subclinical infections possibly participating in the risk of developing this condition.21,24 Advanced maternal age, first pregnancy, poor nutrition, residence at high altitudes, and lack of adequate prenatal care have also been associated with increased risk.24 There is a common thread in all cases: poor placental perfusion associated with maternal vasoconstriction and subsequent maternal multiorgan failure.21

Early identification of preeclampsia increases the likelihood of proper early management and reduction of poor prenatal outcome. Unfortunately, in spite of a great deal of investigation into serum markers that might help to identify women at risk of developing preeclampsia, no reliable markers have been found, nor is there a consistent standard for clinical identification of this potentially devastating condition.21 Similarly, no preventative measures for preeclampsia have been identified with any certainty. Current pharmacotherapy is able to reduce blood pressure and prevent the development of eclampia (preeclampsia with seizures), but it cannot stop the progression of the condition once it is established. Fetal intrauterine growth restriction is a major consequence of this disease. Initial ultrasound at 18 to 20 weeks gestation documents baseline fetal growth. When a woman is diagnosed with preeclampsia, serial ultrasounds at 28 to 32 weeks gestation and then monthly until term, are suggested for objective measurement. Fetal well-being tests such as non-stress tests (NST) and biophysical profile (BPP) are ordered in the third trimester. Fetal movement counts are helpful as a subjective measurement the woman can do at home. A variety of therapeutic strategies have been evaluated for the prevention and treatment of preeclampsia. These are discussed in the following.

Diuretics

Diuretics were once assumed to be a beneficial part of treatment of preeclampsia with its attendant hypertension and edema. However, women with preeclampsia are actually hypovolemic and hemoconcentrated; therefore, the use of diuretics may exacerbate the condition, and thus their use for this condition has been abandoned.21

Salt Restriction

There is no evidence that salt restriction is of any benefit in the prevention or treatment of preeclampsia.25,26

Antihypertensive Medication

Antihypertensive therapy for women with preeclampsia does not affect the underlying disease process or improve mother–baby outcome.26 Further, antihypertensive medications have been associated with adverse side effects, including total placental hypoperfusion; thus, their use is reserved for the treatment of chronic and severe hypertension.26

Aspirin

Data from randomized trials and meta-analysis have been conflicting on the prophylactic and therapeutic effects of low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia. The use of aspirin is predicated on the fact that widely disseminated endothelial dysfunction and platelet disturbances are associated with the etiology of this condition. Low-dose aspirin is thought to be effective because of its thromboxane synthesis inhibition, with consequent reduction in platelet aggregation, as well as its ability to inhibit free radical formation (lipid peroxides) and support of resistance to angiotensin II in pregnant women with increased susceptibility to this vasoconstriction substance.21,27,28 The most recent systematic review of all randomized trials to meet the reviewer’s inclusion criteria (39 trials with a total of 30,563 women) showed a positive safety profile with a moderate, but significant, reduction in the risk of preeclampsia regardless of weeks gestation at trial entry or dose of aspirin. A 15% reduction in incidence of preeclampsia was observed, with an 8% reduction in preterm birth and a 14% reduction in risk of perinatal death.29 In spite of disagreement of the value of aspirin for preeclampsia in earlier studies, all studies have demonstrated that aspirin use in recommended doses during pregnancy appears safe.21 Recent evidence suggests that the earlier in pregnancy that the aspirin is started, the greater the benefit. The recommended dosage range for optimal effects is between 80 and 150 mg per day, specifically to be taken at bedtime.30,31

Calcium

Studies on the efficacy of calcium supplementation for prophylaxis and treatment of preeclampsia have been equivocal. A recent, large, multicenter, randomized prospective trial of 2 g of elemental calcium vs. placebo given to healthy, nulliparous pregnant women beginning in their second trimester showed no differences in the incidence or severity of hypertensive disorders.32 However, a more recent trial demonstrated benefit for women who were at very high risk for developing preeclampsia.33 A proposed mechanism is via prevention of a compensatory rise in parathyroid hormone associated with low serum calcium, and consequently, smooth muscle contraction; however, this remains theoretical.21

Vitamins C and E

Oxidative stress has been proposed as a mechanism associated with the development of preeclampsia. Further, studies have demonstrated decreased levels of antioxidant levels in women with preeclampsia. This has prompted evaluation into the use of vitamin C and E supplements as possibly prophylaxis and therapy. The risk of developing preeclampsia was seen to be lower in high-risk women begun on supplementation at 16 to 20 weeks gestation compared with placebo.21 At this point, the role of antioxidants in this condition remains unclear. For women wishing to supplement vitamin C during pregnancy, it is recommended not to exceed 2000 mg per day to avoid the risk of sensitivity or neonatal rebound scurvy.

Chronic Hypertension

Chronic hypertension is defined as hypertension that predated pregnancy, or hypertension beginning prior to 20 weeks gestation. This diagnosis is not easy to establish in women who have not had care prior to pregnancy and because hypertension prior to 20 weeks gestation can also be indicative of preeclampsia that can occur early in pregnancy in a limited number of conditions.21 Blood pressure levels are less suggestive of poor maternal or fetal outcomes, including fetal growth retardation, prematurity, preeclampsia, placental abruption, and maternal or perinatal morbidity and mortality than are the onset of proteinuria and symptoms of preeclampsia.35,36 The health care professional may order electrocardiography, echocardiogram, ophthalmologic exam, and renal ultrasound. Women with mild hypertension (140 to 159 mm Hg systolic or 90 to 105 mm Hg diastolic) generally do well in pregnancy and, overall, do not need antihypertensive medication. In fact, women already taking antihypertensive medications may need to decrease the dose as some studies have shown decreased uteroplacental blood flow and fetal growth with medication.37 Tapering or stopping antihypertensive medications is done under close observation. Antihypertensive therapies are given to reduce the risk of maternal stroke and cardiovascular complication in women with a diastolic BP of >105 mm Hg. Recommendation of antihypertensive treatment is done when blood pressure levels reach or exceed 160 mm Hg systolic or 100 to 106 mm Hg diastolic, when abnormal laboratory values are found, and certainly with a combination of both abnormal factors. Oral antihypertensive medication with methyldopa or labetalol is typically recommended. Methyldopa does not appear to have negative effects on uteroplacental blood flow.38 Some women, however, do not tolerate it well because of drowsiness. Labetalol, a combined alpha- and beta-blocker, is another choice and can also be prescribed postpartum when breastfeeding. Ideally, women with chronic hypertension need to be evaluated before pregnancy for severity of the hypertension, modification of lifestyle habits and target organ damage (heart, kidney). Women with significant renal impairment (serum creatinine 71.4 mg/dL) may have further deterioration in pregnancy. Women with cardiac abnormalities may have underlying diseases in addition to chronic hypertension. Most women with mild chronic hypertension (140/90 mm Hg) have no end-organ involvement and can have uncomplicated pregnancies.

Gestational (Transient) Hypertension

Elevated blood pressure appearing after 20 weeks without proteinuria and with normal laboratory values in a previously normotensive woman generally results in a good outcome.21 However, gestational hypertension is considered a provisional term. Although most women will not develop subsequent problems, up to 25% will go on to develop symptoms of preeclampsia.39 Women with gestational hypertension appear to be at significantly increased risk of maternal and perinatal morbidity, with elevated rates of preterm delivery, small for gestational age infants, and abruptio placenta compared significantly higher than in the general obstetrical population, and similar to rates reported for women with severe preeclampsia.39 Thus, women with a diagnosis of gestational hypertension should be monitored closely, with weekly prenatal visits optimal. Ultrasound and fetal well-being tests are appropriate in the third trimester. If symptoms of preeclampsia develop, women are treated as is appropriate for that condition. If elevated blood pressure readings persist 12 weeks postpartum, a diagnosis of chronic hypertension is made retrospectively.

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF HYPERTENSION IN PREGNANCY

Cramp Bark and Black Haw

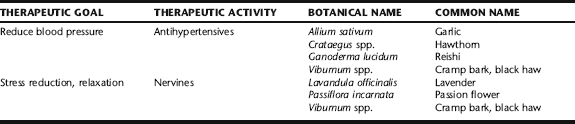

Cramp bark and black haw have been used by midwives as part of herbal antihypertensive protocol for gestational hypertension. Traditionally, they have been used as musculoskeletal relaxants during pregnancy, and to treat irritable uterus, prevent premature labor, and relieve incoordinate uterine contractions.40,41 They are taken in tincture form, either alone or more typically with relaxing nervines and hawthorn, for this purpose in Table 15-3.

Garlic

Garlic has mild antihypertensive properties and inhibits platelet aggregation and inflammation. No studies have evaluated the efficacy or safety of garlic use for pregnancy hypertension. Garlic is a common food used during pregnancy worldwide, and in modest doses is not expected to cause any adverse effects. The German Commission E gives no contraindication to its use during pregnancy, nor does the Botanical Safety Handbook, which does however provide a caution about use during lactation because of active constituents passing through the breast milk. 42 43 44 (McKenna et al. note that the dose of constituents received through breast milk is actually quite small.)43 A randomized control study of 100 primigravid women given either 800 mg/day of garlic tablets or placebo during third trimester pregnancy to evaluate the effect of garlic supplementation on preeclampsia found that pregnancy outcomes were comparable in both groups. There were no reports of side effects in the garlic group other than garlic body odor, and nausea, nor reports of an incidence of adverse fetal outcomes or spontaneous abortion.45 Garlic odor was identifiable in the amniotic fluid of a small group of pregnant women taking garlic supplements.46 It is commonly recommended that because of its antithrombotic effects, garlic use should be discounted 7 days prior to surgery.43 A recent Cochrane review evaluating the effects of garlic on preeclampsia and its related complications concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend increased garlic intake for preventing preeclampsia and its complications, and that side effects have not been reported with its use in pregnancy.47 Although the actual risk of bleeding is uncertain, it is prudent to discontinue the medicinal use of garlic 3 weeks prior to the due date to minimize any increased risk of bleeding, as women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are more likely to enter labor early.

Hawthorn

Hawthorn has been used for treating a variety of cardiovascular conditions, and has noted antioxidant effects and antiplatelet aggregating effects, which may be of benefit in preventing pregnancy hypertension.42,43,48 Other noted actions are an increase in the integrity of blood vessel wall, improvement in coronary blood flow, and positive effects on oxygen use.43 There are no known contraindications or restrictions to the use of this herb during pregnancy or lactation. 42 43 44

Reishi

Although not classically used for the treatment of hypertension in pregnancy, it is worth mentioning that the medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lucidum has demonstrated positive results in research looking at its antihypertensive effects, as well as effects against diabetes and hyperlipidemia. 49 50 51 One interesting study looked at the effects of reishi on glomerular function, and found that it was able to improve hemodynamic flow in glomerular disease and reduce proteinuria. The beneficial effect of Ganoderma lucidum appears to be multifactorial, including the modulation of immunocirculatory balance, antilipid, vasodilator, antiplatelet, and improved hemodynamics. Together with vitamins C and E, this herb helped to neutralize oxidative stress and suppress the toxic effect to the glomerular endothelial function.52 Extracts of reishi polysaccharides have demonstrated significantly improved basal nitrous oxide (NO) release and endothelium-dependent relaxation but without affecting endogenous nitrous oxide synthase (NOS) activity. These results suggest that this herb has the potential to improve endothelium-dependent relaxation in mineralocorticoid hypertension.53 In a study evaluating the clinical effects of lyophilized G. lucidum extract, 53 patients were divided into two groups: Group I consisted of essential hypertensive patients, and Group II consisted of mild hypertensive or normotensive patients. The patients were instructed to take six tablets containing 240 mg of the extract per day. Biochemical and hematologic examination were performed for 21 test items, and the following results were obtained.1 In regard to hypertension, blood pressure significantly decreased in Group I, but did not in Group II, thus showing that G. lucidum has an ameliorating effect on hypertension.2 In regard to biochemical and hematologic effects, the oral intake did not result in any change in the values of any of the 21 test items beyond the normal range, except that total cholesterol decreased slightly and fibrinogen increased slightly. It was therefore concluded that G. lucidum has blood pressure lowering effect on patients with essential hypertension and will not have any side effects on patients with essential or border line hypertension during 6 months oral intake.54 No safety data on use during pregnancy was identified.55 Reishi may be taken alone or in combination with other herbs, and may be taken as a liquid extract or in solid (pill) form (Box 15-4).

BOX 15-4 Protocol for Chronic or Gestational Hypertension

Tincture Formula for Cardiovascular Support

| Hawthorn | Crataegus oxyacantha | 40 mL |

| Cramp bark or black haw | Viburnum spp. | 30 mL |

| Passion flower | Passiflora incarnata | 30 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Nutritional Considerations

A diet rich in calcium, magnesium, and potassium may lessen cardiovascular risk. A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, good-quality oils, and low-fat foods is associated with decreased hypertension and may be especially beneficial for women with chronic hypertension. Essential fatty acids may be beneficial in the prevention of pregnancy hypertension. Vascular sensitivity to angiotensin II was determined in the midtrimester of pregnancy in women after taking a diet with supplemented essential fatty acids and vitamins. The essential fatty acids linoleic and dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid were administered as evening primrose oil capsules (Efamol) for 1 week prior to the study. Vascular sensitivity was then determined in response to 4, 8, and 16 ng kg-1 min-1 angiotensin II. Vitamin supplements (Efavit) were given with the Efamol capsules. Seven women have been studied, and their vascular sensitivity compared with controls on normal diet. The vascular sensitivity was significantly reduced in all the patients on essential fatty acid supplements, and all values fell below the mean of the control group.56

GROUP B STREP (GBS) INFECTION IN PREGNANCY

In the 1970s, Group B Streptococcus (GBS), infection with Streptococcus agalactiae, emerged as a leading cause of pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis in newborns.57 GBS is a normal inhabitant of the intestinal tract and colonizes the vaginal tracts of many women; it can be demonstrated by culture of combined rectal and vaginal swabs in 15% to 40% of pregnant women on random sampling. Most bacterial transmission to the neonate occurs during birth via passage of the baby through the birth canal, or via ascendant bacteria during labor with ruptured membranes. Premature babies and babies of mothers with premature or prolonged rupture of membranes (PROM) are at higher risk of infection. GBS can also cross the membranes, so cesarean section is not protective and carries additional surgical risks to the mother. Infection is categorized as either early or late onset. Early-onset disease symptoms manifest within a few hours, and up to a week after birth. Antibiotic prophylaxis administered to the mother during labor, as is discussed in the following, is used to prevent early-onset infection in the neonate. Late-onset disease develops through contact with hospital nursery personnel and usually manifests in the first 3 months after birth. Up to 45% of health care workers carry the bacteria on their skin, and may transmit the infection to newborns.58 Meticulous hand-washing practices in the hospital are essential for reduction of nosocomial disease transmission.

Although GBS transmission rates are high, the rate of neonatal sepsis is surprisingly low. Unfortunately, the mortality rate associated with early-onset disease can be as high as 50% in premature infants and approaches 25% even in otherwise healthy term infants.58 Over 1600 cases of early-onset infections occur in newborns annually, with as many as 80 deaths per year.57 Long-term sequelae of meningitis in survivors include mental retardation, and hearing or vision loss. The bacterium can also cause maternal bladder and uterine infections; increases the risk of premature labor and premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and stillbirth in pregnant women; and can lead to blood infections, skin or soft tissue infections, and pneumonia in the general population.

DIAGNOSIS

The gold standard test used in screening is a bacterial culture of a sample collection from a simultaneous vaginal and rectal swab. The best time to test for the presence of the organism is between the 35th and 37th weeks of pregnancy.57 Testing at this time is as much as 50% more effective at predicting and preventing perinatal disease than screening earlier in pregnancy, although the numbers of organisms in any individual might fluctuate, making detectable levels variable. CDC guidelines published in 2002 recommend universal screening for pregnant mothers between 35 and 37 weeks gestation.57 The FDA has recently approved a new “quick” test that can diagnose GBS in pregnant women in about an hour. Some studies have shown the test to be up to 94% sensitive, whereas other studies show less consistent results. Because GBS resistance to specific antibiotics has developed, especially to those used for penicillin-allergic women, culture and sensitivity testing is recommended.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published guidelines in 1996 recommending a risk-based (screening) approach, to determine when to recommend intravenous (IV) antibiotic prophylaxis during labor.59,60 It was determined that women with the following risk factors should be offered (IV) antibiotics during labor and delivery, not before labor:

As of 2002, the CDC revised the 1996 guidelines, recommending routine screening for all pregnant women between 35 and 37 weeks gestation, and universal treatment for women who test positive for GBS during pregnancy (Box 15-5).

BOX 15-5 CDC 2002 GBS Treatment Guidelines57

The use of prophylactic perinatal IV antibiotics is attributed with a 70% reduction in the incidence of GBS disease during the last 10 years. In spite of this reduction in incidence, early-onset GBS-related diseases such as pneumonia and meningitis remain a cause of illness and death in newborns in the United States, with a rate of approximately 80 deaths annually.

An alternative conventional treatment to IV antibiotic prophylaxis that has been investigated in Europe but is not employed in the United States other than by midwives, is the use of chlorhexidine vaginal flushings. A randomized controlled study was conducted to investigate the efficacy of intrapartum vaginal flushings with chlorhexidine compared with ampicillin in preventing group B streptococcus transmission to neonates. The study evaluated outcomes of singleton pregnancies delivering vaginally. Rupture of membranes, when present, must not have occurred more than 6 hours prior. Women with any gestational complication, with a newborn previously affected by group B streptococcus sepsis or whose cervical dilatation was greater than 5 cm were excluded. A total of 244 group B streptococcus-colonized mothers at term (screened at 36 to 38 weeks) were randomized to receive either 140 mL chlorhexidine 0.2% by vaginal flushings every 6 hours or ampicillin 2 g intravenously every 6 hours until delivery. Neonatal swabs were taken at birth, at three different sites (nose, ear, and gastric juice). A total of 108 women were treated with ampicillin and 109 with chlorhexidine. Their ages and gestational weeks at delivery were similar in the two groups. Nulliparous women were equally distributed between the two groups (ampicillin, 87%; chlorhexidine, 89%). Clinical data such as birth weight (ampicillin, 3,365 ± 390 g; chlorhexidine, 3,440 ± 452 g), Apgar scores at 1 minute (ampicillin, 8.4 ± 0.9; chlorhexidine, 8.2 ± 1.4), and at 5 min (ampicillin, 9.7 ± 0.6; chlorhexidine, 9.6 ± 1.1) were similar for the two groups, as was the rate of neonatal group B streptococcus colonization (chlorhexidine, 15.6%; ampicillin, 12%). Escherichia coli, on the other hand, was significantly more prevalent in the ampicillin (7.4%) than in the chlorhexidine group (1.8%, p < 0.05). Six neonates were transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit, including two cases of early-onset sepsis (one in each group). In this carefully screened target population, intrapartum vaginal flushings with chlorhexidine in colonized mothers displayed the same efficacy as ampicillin in preventing vertical transmission of group B streptococcus. Moreover, the rate of neonatal E. coli colonization was reduced by chlorhexidine.61 Additional studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this practice, but for unknown reasons it has not been more widely investigated or employed in the United States. 62 63 64 65 This is an option that many midwives in the United States are beginning to employ in home birth settings; clearly more investigation of this option should be conducted to determine whether it is a safe and effective alternative to routine intranatal IV prophylaxis for neonatal GBS infection. Until then, IV antibiotic prophylaxis remains the recommended standard.

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF GBS

Choosing to Use Botanical Therapies for Reducing GBS Infection during Pregnancy

Given the potential narrow time frame between a positive GBS test at 35 to 37 weeks and the time of birth, especially considering the possible need for antibiotic follow-up and the increased risk of premature rupture of membranes and premature labor associated with GBS, midwives may consider an initial culture during pregnancy earlier than the recommended 35 to 37 weeks gestation, particularly in women with a history of chronic UTI or vaginal yeast infection. Although a positive result earlier in pregnancy is not predictive of risk of neonatal infection, earlier testing allows time to address the potential problem using botanical strategies, with a reculture during the predictive period. This approach is consistent with the preventative philosophies of both herbal medicine and midwifery care, and also allows adequate time for more aggressive medical intervention with antibiotics should this be optimal.

Botanical Protocol for GBS

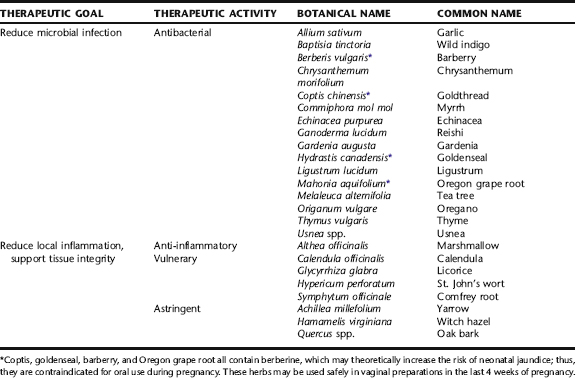

myrrh, thyme, and tea tree oil, to name a few. After an exhaustive search of a number of key medical and chemical databases; however, no clinical trials looking at the clinical treatment or prevention of GBS infection with herbal medicine are available in the world literature. In vitro tests show S. agalactiae to be inhibited by a number of herbs, however, many of these are not safe for use during pregnancy.

Given the paucity of research available directly on this topic, and the long history of clinical efficacy of many botanicals in reducing a variety of infections, including vaginal infections, contemporary herbal practitioners tend to rely on traditional indications of herbs enhanced by contemporary understanding of disease pathology and herbal pharmacology for developing modern clinical applications. Those herbs most commonly used by herbalists, midwives, and naturopathic physicians for the treatment of GBS are listed in Table 15-4. Information on specific categories of herbal actions and exemplary herbs follows.

The basic approach for treating GBS is the nightly insertion of either vaginal suppositories or capsules of antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and vulnerary herbs for a minimum of 3 weeks prior to the onset of labor. The suppositories, which are the most effective delivery model, are typically inserted in the evening, prior to bed, the woman instructed to wear a panty liner to prevent damage to bedding and underclothes from leakage as the suppository melts in the vaginal canal. This melting allows the vaginal and cervical tissue to be slowly bathed in the herbs and emollient. This is repeated nightly for 14 days, a 2-day break allowed, and reculturing done. Some practitioners choose to alternate nightly between the use of a suppository and an inserted capsule or garlic clove. A single “00” capsule can be filled with goldenseal powder and the woman instructed to insert these into the vaginal fornix every other night for the same duration as the suppository protocol. Again, a panty liner is worn. Perianal rinses are also sometimes used if there is heavy colonization or history of repeated urogenital infection. Astringent herbs may be included in topical preparations if there is a great deal of tissue irritation, as they also help to improve tissue integrity and make the tissue less permeable to infection. Douching should be avoided, because it is not an optimally safe practice during pregnancy and may also drive microorganisms upward toward the uterus. The combination of actions of herbs reduces microbial load while reinforcing the integrity of the vaginal tissue, reducing the ability of organisms to colonize in fissures and irritated areas. Probiotics are used concurrently on a daily basis to maximize the body’s ability to produce flora that prevents overgrowth of GBS and enhances the presence of normal vaginal flora. Satisfactorily low levels of the organism should be achieved at least 1 to 2 weeks before the onset of labor. Should GBS bacteriuria persist later than this, an antibiotic protocol can be offered, according to CDC guidelines.

Discussion of Botanical Protocol for GBS

Topical Antimicrobial Treatment

Antimicrobial herbs most commonly included in suppositories for GBS treatment include goldenseal, thyme, oregano, calendula, tea tree, and usnea. They are used in combination in forms most appropriate to each herb, for example, powder, tincture, or essential oil. Discussion of these herbs is found in their individual plant profiles (see Plant Profiles). An example of a suppository recipe, designating proper forms, can be found in the case history for GBS at the end of this chapter, and a discussion of suppository preparation can be found in Chapter 3. Garlic cloves have a long history of use as suppositories for the treatment of vaginal infections. A single garlic clove (not a full bulb!) is carefully peeled to avoid nicking of the garlic flesh, dipped in a small amount of olive oil and inserted into the vaginal fornix and left overnight. Whereas the suppositories and capsule will melt and do not require removal, the clove may fall out on its own when the woman urinates in the morning, or it may need to be manually removed by the woman if it does not spontaneously drop out. The woman can be instructed to remove the clove with a clean finger; some patients may find this offensive, and can be directed to the previous strategies. Capsules are usually filled with only one or two herbs, usually stronger antimicrobials, in powder form. Perhaps most commonly applied is goldenseal root powder, which is inserted on alternate nights to the suppository, as described in the preceding.

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Lisa, a 22-year-old woman, 36 weeks pregnant, tested positive for vaginal group B streptococcal (GBS) infection with routine screening. She was asymptomatic with no accompanying history of vaginal infection or UTI. She was planning a home birth and did not have ready access to intranatal antibiotics because of the political climate of home birth midwifery in her community. Home birth midwifery protocol with GBS is quite strict, and thus her midwife would require her to transport to the hospital for IV antibiotics within 18 hours of ROM, regardless of her stage of labor. Her midwife supported her choice to reduce GBS infection prenatally in the hopes of achieving a negative culture and keeping her birth options open. The following treatment protocol was maintained for 2 weeks, and then Lisa was recultured for GBS.

PRURITIC URTICARIAL PAPULES AND PLAQUES OF PREGNANCY (PUPPP)

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is the most common specific dermatologic condition affecting pregnant women, with an incidence of 1/120 to 1/300 pregnancies.69 Seventy-five percent of women who develop PUPPP are pregnant for the first time, and it is 8 to 12 times more likely to occur in women with multiple gestations.70 PUPPP usually develops in the third trimester, although the condition may have its onset in the postpartum, and rarely earlier in pregnancy.69 PUPPP is referred to as polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (in the United Kingdom), toxemic rash of pregnancy, and late-onset prurigo of pregnancy, although PUPPP is the name most commonly used in the United States.71

Treatment Summary for GBS Prior to Labor Onset

The condition presents as erythematous papules within the striae, usually of the abdomen and thighs, which eventually spread to the extremities and become hives (urticarial plaques). The periumbilical area, breasts, face, palms, and soles usually remain unaffected. The hallmark of this condition is pruritus (itching), which can be extreme, disturbing sleep and preventing normal daily activities. The pruritus of PUPPP can be so uncomfortable as to cause women to feel quite desperate. Pruritus may worsen immediately after delivery, but generally resolves by 10 to 15 days postpartum. Rarely, the condition may resolve prior to birth. Most women do not experience a recurrence with subsequent pregnancies; however, when a recurrence does occur, it is almost always much milder than the original case.69 The condition is not associated with any adverse maternal, fetal, or neonatal outcomes.69

The exact etiology of PUPPP is unknown. One popular theory, supported by the fact that women with larger babies, multiples, or greater maternal weight gain are more likely to develop PUPPP, is that the abdominal stretching of pregnancy leads to an inflammatory response in the connective tissue.69,71 More recently, a maternal response to fetal circulating antigens has been proposed as an etiologic theory, based on the fact that fetal skin tissue has been found in maternal lesions.69,72,73

CONVENTIONAL MEDICAL TREATMENT FOR PUPPP

Treatment for PUPPP consists of high-potency topical steroids, ideally tapering these off after 7 days of therapy. Oral prednisone in doses of 10 to 40 mg/day has been used for severe cases when the pruritus is unbearable to the woman. Symptoms are often relieved after 24 hours of oral treatment. Oral antihistamines are generally ineffective. Early delivery is sometimes discussed when the symptoms are unbearable and treatment is ineffective; however, early delivery does not usually give relief of symptoms.71 Fortunately, symptoms are usually greatly improved with several days of steroid treatment.69 The safety of antenatal steroid use remains controversial; short-term or single course use is advisable, and the safety of use is greater in the third trimester than in the first trimester.

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF PUPPP

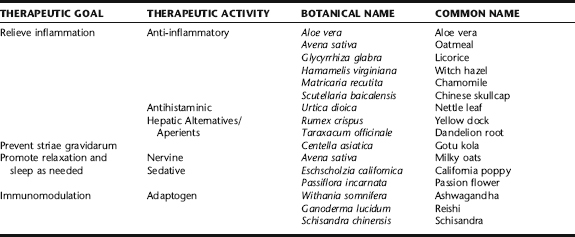

Herbs used to promote sleep are discussed later in Insomnia in Pregnancy.

Treatments are divided into those for topical and internal use, and are recommended to be used in combination. Effects may be expected after 2 to 3 days of regular use, although some women gain relief more quickly and for some it may take up to a week to notice results. Many women report that herbal treatments provide only temporary relief, requiring them to reapply topical remedies often; however, they find this an acceptable alternative to steroid use during pregnancy.

The effects of using oral corticosteroids and herbs internally simultaneously during pregnancy has not been studied, therefore, owing to unknown safety, is not recommended. However, the use of oral steroids and topical herbal treatments, or conversely, oral herbal treatments and topical steroids may be acceptable. Women using oral medications for the treatment of PUPPP should inform their medical provides about their use of herbs prior to beginning an herbal protocol (Table 15-5).

Topical Applications

Chamomile

Chamomile has been approved by the German Commission E for the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions.74 Although there appear to be no contraindications to its use topically or internally (with the exception of rare allergy), herbalists have noted that with some conditions, for example, pediatric eczema, chamomile oil extracts may actually exacerbate irritation. For patients wishing to use chamomile for topical treatment of PUPPP, a cream preparation is advised. Chamomile tea may also be taken internally as a relaxing, mild sleep-promoting tea or tincture.

Chinese Skullcap

Chinese skullcap, “scute,” is used in traditional Chinese medicine to clear heat and drain dampness, which, from a modern medical perspective, might be interpreted as treating inflammation.75 The anti-inflammatory effects are attributed to the herbs flavonoids, and antioxidant and antihistamine activity.75,76 Only recently is this herb finding its way into Western herbal medicine practice. Little published data was identified specifically on the use of Chinese skullcap for skin conditions; however, clinical evidence from herbal practice suggests a high degree of efficacy and safety in the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions including eczema and dermatitis. Tincture may be added to a cream base and applied topically, either alone or mixed with or herbs, for example, licorice root and St. John’s wort extracts. Internal use of Chinese skullcap is not recommended during pregnancy because of teratogenicity in animal studies. It may be used internally, short term, during the postpartum should PUPPP arise during that period, or persists past the time of birth.77

Gotu Kola

Because one of the theories on the etiology of PUPPP is connective tissue damage as a result of abdominal stretching, with manifestation in the striae, it seems a reasonable consideration to minimize striae development if at all possible. A Cochrane Collaboration review of topical agents for stretch mark prevention identified two randomized trials involving a total of 130 women. One study, involving 80 women, indicated that, compared to placebo, massage with a cream (Trofolastin) containing Centella asiatica extract, alpha tocopherol and collagen-elastin hydrolysates was associated with less women developing stretch marks. A second study of 50 women compared massage using an ointment (Verum) containing tocopherol, panthenol, hyaluronic acid, elastin, and menthol with no treatment. Massage with the ointment was associated with fewer women developing stretch marks. The two papers reviewed may show that any cream massaged onto the abdomen, thighs, and breasts (areas most affected by stretch marks) may be of some benefit. There may be additional benefit from certain ingredients in the cream and the ointment described, but it is unknown which constituent(s) is beneficial. Neither preparation is widely available.78 Gotu kola is widely used by herbalists for the treatment of connective tissue damage. Practitioners should be aware that a number of cases of contact dermatitis from topical use were identified in the literature (nonpregnant patients); therefore, caution is advised and patch testing recommended before general use. 79 80 81

Oatmeal Baths

To apply oats topically, the rolled oats are moistened and the milk extracted and added to bath water or rubbed on the body in a bath or shower.82 Two handfuls (about 1 cup) of rolled oats are placed into a large clean sock or rolled in a towel or bandana that can be tied at the top. The sac is taken into the bath or the shower, and as the oats soak up the water the cloth is squeezed firmly in the palm of the hand. A milky liquid will begin to be exuded, and it is this liquid that is allowed to fill the tub or rubbed over the body in the shower, and then rinsed off. This oat milk is very soothing and emollient. This can be repeated as needed even several times daily.

St. John’s Wort

St. John’s wort oil is a classic topical burn treatment.83 Both St. John’s wort extract and hyperforin have demonstrated inhibitory effects in epidermal immune response when applied topically, and suggest a role for this soothing application in the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions. It is popularly used by herbalists for inflammatory and microbial skin conditions. St. John’s wort demonstrates good cosmetic skin tolerance.84,85

Witch Hazel, Aloe Vera

Witch hazel extract, applied as a compress, has long been used as a topical agent for reducing inflammatory and pruritic skin conditions. It is recognized by ESCOP and approved by the German Commission E as a treatment for skin irritations and minor inflammatory dermatologic and mucosal conditions.74,86 A comparative study looking at witch hazel versus cortisone for the treatment of erythema found it to be slightly less effective than cortisone but still noteworthy in its effects, whereas a study on the outcome of treatment of sunburn with witch hazel vs. no treatment found that it led to a significant reduction in erythema and visible skin damage. It has demonstrated a mild anti-inflammatory effect in patients suffering from atopic neurodermatitis and psoriasis.86

Aloe vera gel is a soothing topical liquid from the aloe vera plant. Popular for pain relief and healing from burns and other skin conditions for thousands of years, some women find temporary relief from the itching of PUPPP with topical application of the gel. Promising preliminary research suggests that aloe has immunostimulatory properties that may improve wound healing and dermatologic inflammation.87 There is no contraindication to liberal topical use during pregnancy; aloe should not be used internally during pregnancy.

Internal Use

Dandelion Root, Yellow Dock

An entire category of herbs, known historically and to this day as “alteratives,” and referred to colloquially as “blood cleansers,” are included in the treatment of skin conditions many. Dandelion root is perhaps one of the most commonly used, and is popularly cited on “mother blogs” on the Internet as prescribed by midwives in the treatment of PUPPP. No human clinical trials have been conducted to support the use of dandelion root for skin conditions and there are no data in the scientific literature of dandelion either being safe or contraindicated during pregnancy. 88 89 90 Yellow dock is used similarly to dandelion root. Note that yellow dock is sometimes considered contraindicated in pregnancy because it is a mild anthraquinone laxative; however, clinically, it has not been observed to be associated with increased uterine activity or other adverse outcomes.

Licorice

Glycyrrhizin has exhibited a range of corticosteroid-like activities when injected in animals and humans, including inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis similar to cortisone. Compounds in the root inhibit 5-lipoxygenase formation and leukotriene biosynthesis in vitro.91 It is commonly used by herbalists for a wide variety of inflammatory complaints ranging from gastrointestinal disorders, for which it is best studied, to inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema. Its use for PUPPP is empirically based. Two recent reports on high-dose licorice consumption throughout pregnancy, in the form of licorice candy containing actual licorice extract rather than licorice flavor, demonstrated no increase in maternal hypertension or low birth weight; however, both studies, demonstrated a significant increased in preterm (<37 weeks) delivery. In one study, the risk of preterm delivery was greater than double the risk of women not consuming licorice.92,93 No studies demonstrate harm or adverse outcomes with short-term use of modest doses of licorice, including a study of 110 case reports on the use of glycyrrhizin injections for treating viral hepatitis during pregnancy that showed no adverse effects.88 It is recommended that licorice not be used in excessive doses or for prolonged periods during pregnancy; however, use for up to a week at a time appears to be safe. A comparative study of the safety and efficacy of licorice vs. cortisone use during pregnancy for the treatment of PUPPP would be informative. Women with hypertension should not take licorice during pregnancy (see Plant Profiles for safety information).

Milky Oats

The tincture of milky oats is considered a reliable nerve tonic, especially for use when there is nervous exhaustion or general debility. The medicinal use of oats during pregnancy has not beem studied; however, taken as food, no adverse effects have been noted in pregnancy.82 The tincture may be used alone, but it is more commonly taken in combination with other nervine or sedating herbs, for example, chamomile, St. John’s wort, California poppy, passion flower, and lavender.

Nettle Leaf

Stinging nettle leaf has demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory activity; it is used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and allergic rhinitis.86 Herbalists have found nettle to be a reliable herb in the treatment of numerous systemic and dermatologic inflammatory conditions. It may be taken as tea or in freeze-dried capsules. No serious adverse effects were reported in five clinical studies with a total of 10,368 patients using hydroethanolic extracts corresponding to an equivalence of 9.7 g of dried leaf daily for periods ranging from 3 weeks to 12 months. Minor side effects included GI upset and allergic reaction (1.2% to 2.7% of cases).86 Nettle leaf is one of the most commonly used herbs by midwives who commonly recommend it to help build iron levels (see Chapter 15). It has been suggested, although not demonstrated, that the astringency of this herb might interfere with iron absorption. A 1975 review article by Farnsworth et al. reported that stinging nettle was a potential abortifacient, and that its constituent 5-hydroxytryptamine was a uterine stimulant; however, frequent use of large doses of this herbal infusion in midwifery practice has demonstrated no evidence of such activity.

Baking Soda Paste

BOX 15-6 Herbal Protocol for PUPPP

Mix

| St. John’s wort | (Hypericum perforatum) |

| Skullcap | (Scutellaria baicalensis) |

| Licorice | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) |

Internal Treatment

| Nettle leaf tincture | (Urtica dioica) | 30 mL |

| Licorice root | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | 30 mL |

| Dandelion root | (Taraxacum officinale) | 20 mL |

| Passion flower | (Passiflora incarnata) | 20 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

VARICOSITIES IN PREGNANCY

Varicosities are exceedingly common during pregnancy, when they often appear for the first time. Forty percent of all pregnant women are affected.94 They most commonly appear on the lower legs and rectum (hemorrhoids), although vulvar varicosities may also occur. The physiologic changes of pregnancy are responsible for the development of varicosities. These include hormonal changes that cause increased fragility of the blood vessel walls, along with increased iliac venous pressure owing to the enlarging uterus, leading to reflux of blood in the vessels and subsequent, rupture of valves, and the appearance of varicosities.94 More recently, the “weak-wall hypothesis” proposes that varicosities arising in pregnancy are actually the result of an inherited predisposition to weakness in the vein wall that allows progressive venous dilation even at normal venous pressures, with valve failure occurring as a consequence.95 Further, it is now recognized that the saphenous veins contain estrogen and progesterone receptors that may play a role in pregnancy-mediated varicose vein development, although the role of these receptors is not entirely known.95,96

Varicosities may be accompanied by throbbing, a feeling of heaviness, aching, heat, and pain, and with leg varicosities there may be ankle edema and phlebitis. Varicosities frequently regress in intensity during the postpartum; however, they may also persist, with continued symptoms and worsening of venous distention.97 Hemorrhoids are predisposed to bleed and are further aggravated by constipation, which also commonly increases in pregnancy. Venous thrombosis is a complication that occurs in less than 10% of pregnancies, and which requires immediate medical management. In severe cases, and especially in the postpartum and as women age, chronic venous insufficiency, and venous ulceration can become problematic. These conditions, too, require medical care in conjunction with complementary therapies.

TREATMENT OF VARICOSITIES IN PREGNANCY

Supportive therapy for leg varicosities includes leg elevation, compression with support hose, sleeping in a left lateral decubitus (side-lying) position, regular exercise, and avoidance of long periods of standing or sitting.95,97 Anticoagulant therapy is used when needed to prevent thromboses. Hemorrhoids are treated with topical antihemorrhoid preparations and avoidance of straining when having a bowel movement. Excessive periods or sitting or standing should be avoided. Surgical treatment for hemorrhoids is rarely required during pregnancy; when surgery is required for either hemorrhoids or leg varicosities, it is preferably done between pregnancies.95 Most often, vulvar varicosities also require only supportive treatment; severe vulvar varicosities may require attention during vaginal birth to prevent them from rupturing and bleeding extensively.

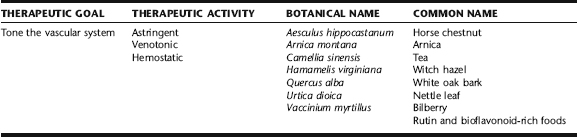

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF VARICOSITIES IN PREGNANCY

There is very little published evidence in either the herbal or scientific literature on the use of botanicals for the prevention or treatment of varicosities in pregnancy. Topical treatments that include horse chestnut and witch hazel extracts are commonly recommended. Black tea (tea bags) are commonly used by midwives as a highly astringent “home remedy” used topically for the treatment of hemorrhoids, both during pregnancy and postnatally. Other herbs that may be used topically include witch hazel, yarrow, and white oak bark. Arnica may sometimes be recommended for external use, but should not be used on broken or open skin. The use of nettle leaf infusion, taken regularly as a tea, is often recommended for its reputed hemostatic and venotonic actions. Horse chestnut is a popular herb in Europe, taken internally for the treatment of venous insufficiency. Bilberry is an important venotonic herb used internally with a good safety for pregnancy. Foods high in rutin and bioflavonoids are commonly used to improve vascular tone and integrity. The herbal approach to the treatment of hemorrhoids includes gentle measures to alleviate constipation if this is a concurrent problem, and thus minimize straining during bowel movements. Gotu kola, which is sometimes used for varicosities and venous disorders is not safe for internal use during pregnancy, and has been associated with contact dermatitus with topical use, so it is recommended that patch testing be done before applying liberally (Table 15-6). 98 99 100 101

Arnica

Topical arnica applications are sometimes included in treatment protocol for varicosities. According to Schulz et al., it is uncertain whether arnica extracts are active topically and if so, by what mechanism.102 Clinical herbalists, however, report on the remarkable and rapid ability of arnica flowers to reduce bruises and swellings when applied topically to the affected areas. No studies were identified on the use of arnica for the treatment of varicosities. The herb is most commonly applied as an oil or gel, is not applied to broken skin, and should not be used internally. The oil may be applied two to three times daily, either alone or in combination with other herbal preparations. As the rectal mucosa is highly vascular and absorptive, it is recommended that arnica be used for leg varicosities only, and that other herbs (e.g., witch hazel, black tea) be used to reduce hemorrhoids.

Bilberry

Bilberry, a relative of the blueberry, is used as a vasoprotective herb, one of its many virtues. It has demonstrated potent effects on vascular permeability in animal and in vitro models, and a number of positive human trials have been done, tough their methodologic quality was not strong.98 Bilberry has been reported to be safe for internal use during pregnancy, and efficacious in the treatment of gestational hemorrhoids and venous insufficiency of pregnancy.103 It is taken in two and three divided doses of 160 to 340 mg per day, depending upon the severity of the condition.103 It may also be taken in liquid extract form. Bilberry can be taken prophylactically in women with a predisposition to varicosities or a family history of gestational varicosities.

Horse Chestnut

Horse chestnut seed extract (HCSE) preparations are widely prescribed in Europe for the treatment of venous insufficiency and vascular fragility. They are taken orally. A review of the scientific literature yields seven well-designed studies that support the superiority of HCSE over placebo and suggest that the herbal product may be equal to compression stockings in efficacy.98 Although the herb is generally not recommended for use in pregnancy, this is owing to lack of data rather than contraindication based on known adverse effects. No teratogenic effects have been observed in animals given very high doses of extract by oral route, although fetal body weights were reduced compared with controls.104 Steiner et al. conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of HSCE use during pregnancy. Fifty-two women with leg edema owing to pregnancy-induced venous insufficiency received 300 mg of Venostasin (240 to 290 mg of HSCE standardized to 50 mg escin) twice daily for 2 weeks. No adverse effects were observed (Fig. 15-1).105

Nettle Leaf

Nettle leaf is highly valued by herbalists for its purported venotonic actions, and is used by herbalists and midwives for the treatment of varicosities.106 It is taken internally as a strong daily nutritive infusion. Its use is empirically based. No herbal or scientific studies were identified on the use of nettle leaf for the treatment of varicosities. Animal studies are lacking on the use of this herb in pregnancy. No harmful effects to the fetus have been identified. The lignins in nettle, as well as their intestinal transformation products, have been shown to bind sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) in vitro; however, ethanol extract of the aerial parts of nettle did not demonstrate significant anti-implantation activity when given to female rats.104

Witch Hazel, Black Tea, White Oak, Yarrow

Witch hazel bark, black tea, and white oak bark are tannin-rich, highly astringent herbs commonly used as topical remedies for the treatment of hemorrhoids. Yarrow is also quite astringent, and although more commonly used for bleeding, may sometimes be included in topical preparations. These herbs are not intended for internal use in pregnancy (with the exception of small amounts of black tea as a beverage). They can be used in a variety of forms including as strong washes or diluted extracts applied with a cotton ball, or in herbal suppositories (see the following) to be inserted nightly to reduce local swelling and inflammation. Black tea bags are a very convenient and acceptable remedy, as they are easily accessibly, affordable, and simple to prepare. Women can be instructed to purchase commercial tea bags and steep 1 per application in ¼ cup of boiling water (as if making a cup of tea with a very small amount of water). When the tea has cooled, the liquid can be discarded and the tea bag slightly wrung out and the bag applied to the hemorrhoids. Women must be warned that the tea will permanently stain fabrics and bedding. Putting a menstrual pad in an old pair of underwear on to hold the tea bag in place for up to 30 minutes at a time is effective, or the woman can simply apply the tea bag manually for several minutes, sitting over the toilet or in the shower, two to three times daily (Fig. 15-2).

Food Sources of Rutin

Rutin is a naturally occurring flavonoid in many foods, especially buckwheat, apricots, cherries, grapes, grapefruit, plums, and oranges. It is often used in patients with capillary fragility, varicose veins, bruising, or hemorrhoids.107 Most clinical studies have used hydroxyetylrutosides (HER), a standardized mixture of rutinosides. In a study of 37 pregnant women given 300 mg rutoside three times daily for 8 weeks vs. placebo, rutoside reduced symptom scores for pain, feelings of leg heaviness and tiredness, nocturnal cramps, and paraesthesias associated with varicosities compared with placebo in women with visible varices and these symptoms after 28 weeks gestation. Rutosides also have led to reduction of ankle size compared with placebo, in whom ankle size increased. Adverse effects are rare and transient. The most commonly reported adverse effects include dizziness, headache, dry mouth, tiredness, nausea, dyspepsia, diarrhea, constipation, and skin rash. Rutin appears to be safe during pregnancy. Its safety after 28 weeks of gestation has been confirmed in two human trials. Scientific evidence for the safe use of rutin during lactation is not available. Given the uncertainty of the safety of rutoside preparations, it is recommended that pregnant women consume foods rich in rutin and take a complete vitamin supplement with bioflavonoids, including rutin, rather than a rutoside product.107

INSOMNIA IN PREGNANCY

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders has proposed that the occurrence of either insomnia or excessive sleepiness that develops during pregnancy be called pregnancy-associated sleep disorder in recognition of the association of sleep disturbance with pregnancy and the self-limited nature of these problems.108 In nonpregnant populations, sleeping less than 5 hours per night has been observed to adversely impact both mood and performance, and places individuals at increased risk of adverse events such as motor vehicle accidents.108 Postpartum sleep deprivation may increase the risk for mood disorders ranging from postpartum depression to overt psychosis.108 Disrupted sleep during pregnancy is associated with poorer obstetric outcomes, in particular length of labor and type of delivery. In a prospective, longitudinal follow-up of 131 pregnant women, Lee and Gay demonstrated that women who slept less than 6 hours at night had longer labors and were 4.5 times more likely to have cesarean deliveries.109 Given the potential magnitude of adverse events associated with sleep disturbances, serious attention should be given to this complaint during pregnancy, and its effects on a woman’s quality of life and health.

Physiologic, hormonal, and physical changes of pregnancy are responsible for a variety of sleep disorders. Women may experience insomnia, night waking, parasomnias [e.g., restless leg syndrome (RLS)], leg cramps, hypersomnia, or snoring. 109 110 111 The growing uterus and the pressure it places on the lower back diaphragm, stomach, and simply its weight, require pregnant women to adopt a variety of positions to accommodate in order to sleep comfortably and avoid associated discomforts for example, heartburn, or pressure on the inferior vena cava leading to paresthesias of the distal extremities and shortness of breath. Increased need to urinate during the night, exaggerated dreams, worries over the increased responsibilities of pregnancy and parenthood, anxieties over the birth, and many other concerns also can interfere with sleep and severely decrease its quantity and quality. The effects of estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy also alter the quality of sleep, although the extent to which this occurs as a result of hormones is not clear. However, indirectly, hormonal effects such as increased nasal congestion, can dramatically affect sleep.109,112 Pregnancy may also exacerbate existing sleep disorders, or exacerbate medical conditions (e.g., acid reflux, asthma) that affect sleep. Chronic pain is a common cause of sleep disturbances, and may also be exacerbated during pregnancy (see Case History).

Sleep disorders of pregnancy have a predictable pattern relative to the trimesters. During the first trimester, sleep duration and quality at night are often decreased, although women to require more and report that they are apt to fall asleep much more easily than usual during the day, commonly with an increased desire to nap. The second trimester usually leads to a return of a woman’s normal sleep patterns. In the third trimester, women show increased wake after sleep onset and decreased sleep quality, and frequently complained of restless sleep, leg cramps, and frightening dreams. 109 110 111 Some amount of night waking during pregnancy may be the body’s natural and intrinsic way of preparing the mother for the inevitable night waking that accompany having a breastfeeding newborn and infant, and therefore, regardless of treatment, may be unavoidable.

Lack of sleep or poor sleep quality can affect a woman’s sense of well-being during her waking hours, increase irritability, lead to depression, decrease appetite, can affect memory, and may affect concentration and functioning at normal daily tasks. As discussed earlier, significantly diminished sleep during pregnancy may also have a deleterious effect on the birth experience.109

MEDICAL TREATMENT OF INSOMNIA IN PREGNANCY

The exact incidence of sleep disorders in pregnancy is unknown, but it is estimated that as many as 90% of women experience them during the third trimester.108,109 There are no clinical trials of various treatment

Treatment Summary for Varicosities and Hemorrhoids during Pregnancy

modalities in this group of patients.110 It is important to identify etiological factors and to treat any associated or underlying medical conditions. RLS may represent folate or iron deficiency, hormonal changes of pregnancy, or more rarely, may be a sign of end-stage renal disease or peripheral neuropathy.113 It is usually transient in pregnancy, occurring most commonly in the third trimester and disappearing by the time of birth.113 Insomnia associated with a more serious psychiatric disorder, for example, severe depression, anxiety disorders, or bipolar disorder, may require specific pharmaceutical treatment. Risks associated with the use of pharmaceutical medications during pregnancy must be seriously considered.

The medical treatment of RLS in pregnant women is difficult, as most of the drugs commonly used for this problem are not safe for use during pregnancy. Nonpharmacologic treatments are recommended, such as leg stretching prior to sleep and support hose if varicosities are prominent. Iron supplementation is suggested, as this condition is associated with iron deficiency. Opioids are used sometimes in the second or third trimester in severe cases.114

GENERAL TREATMENT OF SLEEP DIFFICULTIES IN PREGNANCY

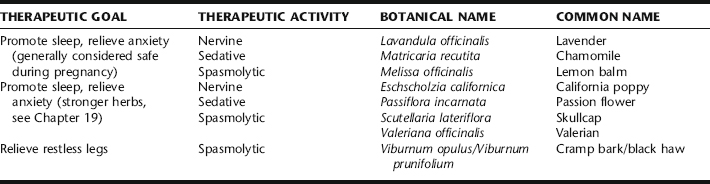

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF INSOMNIA IN PREGNANCY

There is a limited range of safe conventional pharmaceutical options for treating insomnia during pregnancy, and interestingly, most pregnant women do not report sleep disorders to their physicians.108 It is nonetheless a problem for which women commonly seek relief, and therefore frequently turn to natural products. It is essential that the normalcy of symptoms, for example, RLS, be established prior to treating. However, once it is determined that the sleep disturbance is a simple pregnancy discomfort, gentle herbal therapies may be tried. Several herbal medicines appear to be safe during pregnancy and provide modest improvement in sleep quality; however, experimental and clinical data on the use of these during pregnancy is, with minimal exception, lacking. General recommendations should incorporated prior to or in conjunction with botanical use. For women with severe sleep disorders but who are not willing to use pharmaceutical drugs, stronger herbs may be considered; however, because studies evaluating their safety during pregnancy are largely lacking, their use should be limited to short term, and first-trimester use should be avoided. Examples of such herbs include passion flower (Passiflora incarnata), skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora), California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), and valerian (Valeriana officinalis). Herbs commonly used during pregnancy for difficulty falling asleep or poor sleep quality, and which have a good safety profile, are presented in the following; further discussion of the evidence for these herbs, as well as additional herbs for insomnia, is presented in Chapter 19. Readers are also directed to Chapter 19 for insomnia secondary to anxiety. Consult Plant Profiles for pregnancy-related safety information.

Teas are an excellent form for using sleep promoting aromatic herbs such as chamomile, lavender, and lemon balm; unfortunately, drinking tea close to bedtime often causes the pregnant woman to awaken within a couple of hours after falling asleep with the need to urinate, thus defeating the benefits of the herbs. Therefore, it is recommended that tea not be taken closer than 2 hours prior to bed, and that frequent small amounts of tincture be taken instead to build an effective dose over a period of 1 to 2 hours, with a dose of 2 mL of any single herb or a combination of any two or three, taken every 15 to 30 minutes for 1 to 2 hours prior to attempting to sleep (Table 15-7).

Chamomile

Chamomile is commonly taken as a tea, although may also be included in tincture formulae, as a gentle calming and sleep-inducing herb.115 Clinical trials are generally lacking. Studies in mice and rats have shown anticonvulsant and CNS depressant effects respectively.115,116 Chamomile is erroneously placed on lists of herbs contraindicated during pregnancy; however, this is based on a single 1979 study that found teratogenic effects using a concentrated extract of α-bisoprolol at high doses. No teratogenic effects were seen at lower doses and the dose of the oil constituent required to cause teratogenicity are far greater than it would ever be possible for someone drinking the tea to ever approximate.117 No harmful effects have been reported from the use of chamomile during pregnancy or lactation.

Cramp Bark/Black Haw